Abstract

Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis (Ftt) is extremely virulent for humans when inhaled as a small particle aerosol (<5 µm). Inhalation of ≥20 viable bacteria is sufficient to initiate infection with a mortality rate ≥30%. Consequently, in the past, Ftt became a primary candidate for biological weapons development. To counter this threat, the USA developed a live vaccine strain (LVS), that showed efficacy in humans against inhalation of virulent Ftt. However, the breakthrough dose was fairly low, and protection waned with time. These weaknesses triggered extensive research for better vaccine candidates. Previously, we showed that deleting the clpB gene from virulent Ftt strain, SCHU S4, resulted in a mutant that was significantly less virulent than LVS for mice, yet better protected them from aerosol challenge with wild-type SCHU S4. To date, comprehensive searches for correlates of protection for SCHU S4 ΔclpB among molecules that are critical signatures of cell-mediated immunity, have yielded little reward. In this study we used transcriptomics analysis to expand the potential range of molecular correlates of protection induced by vaccination with SCHU S4 ΔclpB beyond the usual candidates. The results provide proof-of-concept that unusual host responses to vaccination can potentially serve as novel efficacy biomarkers for new tularemia vaccines.

Keywords: tularemia, Francisella tularensis, live attenuated vaccine, transcriptomics, correlates of protection

1. Introduction

Francisella tularensis subspecies holarctica (Fth) and subspecies tularensis (Ftt) are zoonotic facultative intracellular bacterial pathogens, capable of causing a spectrum of diseases collectively called tularemia (reviewed in [1]). Both subspecies can cause serious infections in humans dependent on their portal of entry into the host. Ftt is particularly lethal for humans when inhaled as a small particle (<5 µm) aerosol. In this situation as few as 20 inhaled colony forming units (CFU) of Ftt can cause systemic potentially lethal infection (≥30% mortality without effective treatment) [2,3,4,5]. In contrast, [6,7], Fth rarely results in death regardless of how it enters the host [8,9].

The high mortality associated with inhalation of low doses of Ftt made it a major focus of biological warfare programs during the last century [10,11,12,13,14]. To counter this threat, US scientists obtained a live attenuated Fth vaccine strain, strain S15, from Russia from which they derived what became known as Fth live vaccine strain (LVS) [15]. Its efficacy following scarification, aerosol, or oral administration was demonstrated in human volunteers in the early 1960s [16,17,18,19] and in field trials on tularemia researchers [20]. Overall, LVS given by scarification was particularly effective against subsequent intradermal (ID) infection with virulent Ftt strain, SCHU S4, but appeared suboptimal against aerosol challenge. Against the latter, aerosol immunization was more effective, but caused mild to moderate tularemia when administered at the most efficacious doses [19,21]. Consequently, scarification is the sole administration route recommended for humans. However, LVS remains unlicensed and is unavailable for general use.

The emerging threat of bioterrorism at the beginning of this century, triggered by the dissemination of anthrax spores through the US mail system, led to renewed interest in developing countermeasures against potential bioweapons in general, including vaccines against Ftt [22]. Our approach to the latter was to make gene deletion mutants of SCHU S4 and to test any strains that were at least as attenuated as LVS for their ability to protect mice from either ID or respiratory challenge with virulent Ftt [23,24,25,26,27]. Only one out of sixty mutants tested fulfilled our criteria; a mutant, SCHU S4 ΔclpB, from which the chaperonin gene, clpB, was deleted [24,25,26,27,28]. Given intranasally (IN) to mice, SCHU S4ΔclpB (hereafter ΔclpB) was less virulent than LVS, and administered ID was more efficacious against aerosol or intranasal (IN) infection with fully virulent Ftt. We also generated other highly attenuated mutants with lesser degrees of efficacy than ΔclpB or LVS [24,25,27]. For both respiratory and ID challenge only vaccination with ΔclpB proved to be superior to LVS. The reason for this superior protection remains unknown, despite concerted efforts to define differences in the host molecular immune response to vaccination with ΔclpB vs. LVS and other attenuated strains of varying efficacy [24,26,27,29].

The literature overwhelmingly shows that canonical cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses rather than antibody responses to vaccination with LVS account for its protective capabilities (reviewed in [30,31]). However, no vaccines currently in clinical use have ever been approved based on the CMI responses they evoke, even when this is the presumed mechanism of action. Another major developmental hurdle for tularemia vaccines is the dearth of natural respiratory infections with Ftt that precludes the usual use of large-scale phase 3 clinical trials to determine their efficacy in humans. Instead, the US FDA has developed a policy known as “The Animal Rule” to enable licensing of countermeasures against Ftt and other potential biological weapons [32,33]. Specifically, this regulatory pathway allows for evaluation of novel vaccine efficacy using appropriate animal models of infection that lend themselves to a rational means to bridge their correlates of protection (CoP) to human immune responses to vaccination. With these issues in mind others have used a variety of CMI- and antibody- based assays using material obtained from various hosts, including humans, immunized with LVS in search of putative pan-specific immune CoP [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

In contrast, we have compared antibody and CMI responses in mice immunized ID with experimental vaccine strains of varying efficacy in BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice. These include extensive immunoproteomic studies to determine the antibody repertoires elicited by these experimental vaccines and kinetics of production of selected cytokines and chemokines in the skin, lungs, livers, spleens, and blood of mice at various times following vaccination or challenge. These have essentially left us empty handed save for the fact that using three distinct vaccination regimens, protection was associated with elevated pulmonary IL-17 levels on day 7 after IN challenge with SCHU S4. However, for a fast-acting pathogen such as F. tularensis, CoP need to be detectable as early as possible after vaccination rather than after challenge. In this regard, the multiplex assays for cytokines and chemokines are limited by the relatively small range of antibodies available that are primarily aimed at detecting canonical immune responses, whereas recent transcriptomics and other molecular immunological approaches have shown that non canonical host responses can predict protective responses elicited by vaccines against several other pathogens and LVS in experimental animals and humans [34,35,37,40,41,42,43,44]. Therefore, we were interested to see whether a transcriptomics approach bolstered by a concomitant change in the level of selected associated proteins would reveal unique and robust CoP against respiratory challenge with SCHU S4 induced by immunization with ΔclpB.

2. Methods

2.1. Bacteria

The SCHU S4 mutants were generated as previously described [23] and their safety and efficacy characteristics are summarized in Table 1 along with those of LVS. SCHU S4 is a virulent Ftt strain with an LD50 for mice of <10 CFU by ID, IN, and aerosol routes of challenge and has been described by us previously [46].

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of F. tularensis strains used in the current study.

| Mutant | IN LD50 (CFU) |

ID LD50 (CFU) |

Survival against ID Challenge with SCHU S4 a | Survival against Respiratory Challenge with SCHU S4 b | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVS | 103 | >107 | 100% | 0–20% | [24,25] |

| ΔclpB | >104 <106 c | >107 | 100% | 60–100% | [24,27,47] |

| ΔgplX | NT | >107 | 80% | 0% | [27] |

| ΔlpcC | >103 <105 | >107 | 0% | 0% | [47] |

a Challenge dose ≤ 105 CFU; b IN or aerosol challenge dose ≤ 200 CFU; c range from multiple tests.

2.2. Vaccination of Mice

Young adult female BALB/c mice (n = 4/group) were immunized ID with 105 CFU of one or other of the vaccine strains listed in Table 1. Immunization was performed by inoculation of 50 µL of bacteria at a concentration of ~2 × 106 CFU/mL into the shaved mid-belly. The formation of an overt bleb at the site of inoculation was deemed to be indicative of successful ID administration. Four days after vaccination, mice were killed and serum was prepared from whole blood, and spleens were removed intact. Untreated mice were used as negative (naïve) controls. This work was performed under National Research Council Canada animal use protocol # 2015.01 in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines for the use and care of laboratory animals (https://ccac.ca/en/standards/guidelines/; accessed on 6 July 2021). For IN challenges, 10 µL of inoculum was added to each nostril of mice whilst under general anaesthesia followed by 10 µL of saline to chase the challenge inoculum into the lower airways.

2.3. Transcriptomics

Total RNA was isolated from the spleens of mice vaccinated ID with LVS or one of the SCHU S4 deletion mutants ΔclpB, ΔgplX and ΔlpcC, (4 spleens from each group treated individually throughout) using Tri reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Genomic DNA contamination was removed by Turbo DNA-Free Kit (Life Technologies). RNA quality was assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. RNA-Seq Libraries were generated using the TruSeq strand RNA kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The RNA-Seq libraries were quantified by Qbit and qPCR according to the Illumina Sequencing Library qPCR Quantification Guide and the quality of the libraries was evaluated on Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 using the Agilent DNA-100 chip. The RNA-Seq library sequencing was performed using Illumina Hi-Seq2000 (Genome Quebec, Montreal, QC, Canada). RNA-seq data are available in the GEO repository with access number GSE186408. STAR (v2.7.8a) [48] was used for alignment of the reads to the reference genome and to generate gene-level read counts. Mouse (Mus musculus) reference genome (version GRCm39 Gencode M26) [49] and corresponding annotation were obtained from Gencode (https://www.gencodegenes.org/mouse/stats.html (accessed on 2 February 21) and used as reference for RNA-seq data alignment process. DESeq2 [50] was used for data normalization and differentially expressed gene identification for each treatment vs. naïve samples. The expression value of each gene was expressed as average read counts. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were obtained by comparing treated samples with naïve samples (control) and all vaccinated samples compared with each other. A q-value (adjusted p-value) of less than 0.05 and 2 fold change in ratio (abs (log2 fold-change) ≥ 1) were used to generate a DEGs list. KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were done using GOAL software; pathway enrichment p-values were computed using the Fisher’s exact test via the hypergeometric distribution and were BH corrected [51].

2.4. Multiplex and ELISA Assays

A commercial ELISA kit (My BioSource Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to determine relative levels of Saa3 in mouse sera in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sera were tested at 1:2000 and 1:10,000 dilutions. Serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 1 (TIMP1), granzyme B, matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 8 (MMP3/8) were determined by Luminex using immunomagnetic multiplex kits (MilliporeSigma, Oakville, ON, Canada). Data were analysed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-test for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptomic Analysis

For reasons of cost and data handling logistics, we chose to examine the transcriptome in the spleens of BALB/c mice four days after ID immunization with one or other of the strains of F. tularensis listed in column 1 in Table 1. The spleen was chosen as a substitute for PBMC which are in short supply from individual mice, and day 4 was chosen because that was the time when most splenic cytokine and chemokine levels peaked in our earlier studies using multiplex analysis [27].

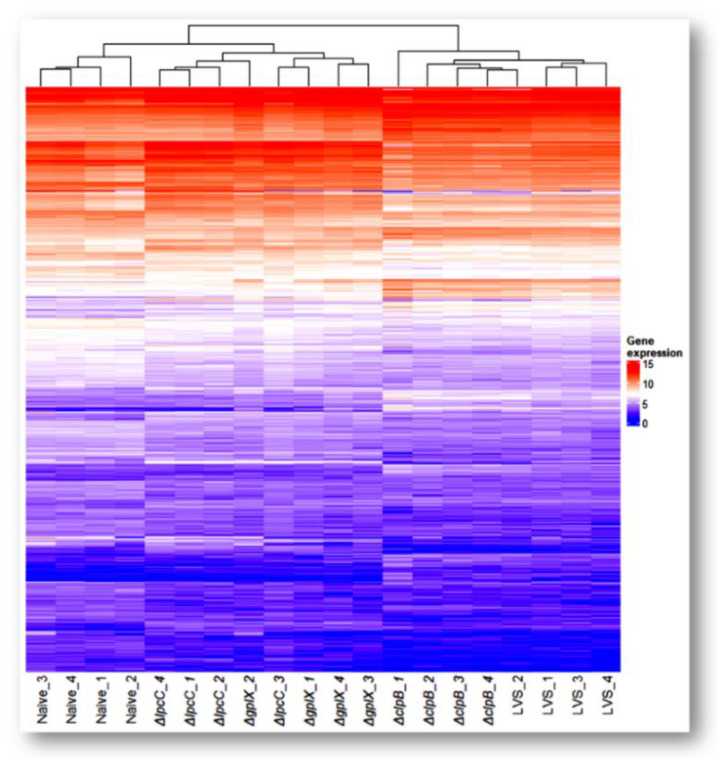

On average, 85% of the 34 million paired-end reads in each sample were mapped to the mouse genome. A total of 5361 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were collectively identified from the 4 pairwise comparisons between the vaccines and the naïve control (Figure 1, Table 2 and Table S1). Compared to spleens from naïve mice, 3539, 3242, 2006 and 1350 genes were differentially expressed after vaccination with ΔclpB, LVS, ΔgplX and ΔlpcC, respectively. The number of changed genes reflects the extent of host response to vaccination and appears to correlate with the efficacy of the vaccine strains, with ΔclpB > LVS > ΔgplX > ΔlpcC.

Figure 1.

Transcriptome overview. Heatmap of expression profile of differentially expressed genes across four vaccine strains. Genes that changed their expression levels significantly (p < 0.05) in at least one of the vaccinated samples when compared with the naïve sample were extracted from the data set. All four replicates of each sample group were included to show reproducibility. A total of 5361 genes were compiled. Data values were log2 transformed.

Table 2.

Number of differentially expressed genes between each comparison.

| ΔclpB/ Naïve |

LVS/ Naïve |

ΔgplX/ Naïve |

ΔlpcC/ Naïve |

ΔclpB/ LVS |

ΔclpB/ ΔgplX |

ΔclpB/ ΔlpcC |

LVS/ ΔgplX |

LVS/ ΔlpcC |

ΔgplX/ ΔlpcC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up | 1362 | 1037 | 916 | 1015 | 108 | 961 | 1475 | 358 | 897 | 233 |

| Down | 2177 | 2205 | 1090 | 335 | 31 | 1219 | 1926 | 722 | 1546 | 164 |

Cluster and heatmap analyses of the 5361 genes showed distinct patterns of gene expression for each vaccine strain (Figure 1). Mice immunized with ΔclpB and LVS formed one branch, while the other two vaccines and naïve mice formed another branch. Thus, immune responses to ΔgplX and ΔlpcC are more similar to naïve mice than to mice immunized with ΔclpB or LVS. Although the overall host responses to ΔclpB and LVS are closely related, there were 139 DEGs when we did pairwise comparisons between these two strains (Table 2). Likewise, the patterns produced by ΔgplX and ΔlpcC were similar to each other with 397 DEGs between this pair (Table 2).

The geneID, normalized mean read counts and log2 ratio of these changed genes are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Reassuringly, Il-6, IFNγ, and Il-17 transcripts were among the top twenty that were significantly overexpressed in mice immunized with ΔclpB versus the other SCHU S4 mutants as this is in keeping with our previous findings examining the relative levels of these proteins in the spleens of similarly vaccinated mice [27]. Additionally, upregulation of Il-1α, Il-1β, Cxcl1 and ccl2 (MCP-1) transcripts, though lower down the ranking, also concurred with our prior multiplex studies. They essentially followed the pattern ΔclpB > LVS > ΔgplX > ΔlpcC. This is in overall agreement with the relative protection these strains administered ID provide against respiratory infection with SCHU S4 (Table 1).

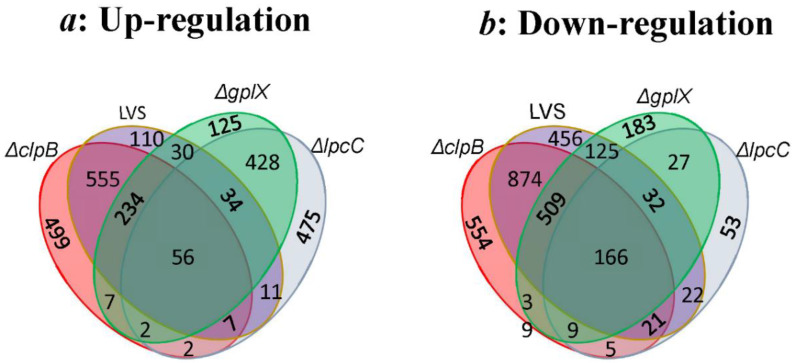

Figure 2 illustrates the number of genes identified to be changed uniquely in one or simultaneously in two or more samples (up in Figure 2a, down in Figure 2b). As expected, ΔclpB had the highest number of uniquely differentially expressed genes (499 up, 554 down). ΔclpB and LVS clearly shared the highest number of up- and down- regulated genes, 852 and 1576 respectively, since they both protect against respiratory challenge, albeit to different extents. A large number of up- (290) and down- (675) regulated genes were shared by ΔclpB, LVS and ΔgplX as these vaccines all protect against intradermal challenge. While ΔlpcC shares some (520 up, 234 down) of the DEGs with ΔgplX, it shared very few DEGs with ΔclpB and LVS, individually, or with both. There are 56 and 166 commonly up- or down- regulated genes in all 4 samples; they are likely genes responding to general vaccination regardless of the mutant strain used (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Numbers of differentially expressed genes in all 4 samples illustrated by Venn diagram. All up- (a) or down- (b) regulated genes, relative to spleens from naïve mice in each sample are encompassed in a colored oval. Shared genes are indicated by numbers situated on appropriate overlapping areas.

Further study of KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of the differentially expressed genes in the three strains that conveyed some levels of protection against challenges revealed several pathways that are expected to be up-regulated after vaccination (Table 3). The most significant pathway is the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway, followed by NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (families of pattern recognition receptors responsible for detecting various pathogens and generating innate immune responses), chemokine signaling pathway and antigen processing and presentation, as well as IL-17, TNF signaling and viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor pathways. For ΔclpB, in addition to the genes that were shared with the LVS and ΔgplX, there were many more genes that were up-regulated in these pathways. No direct link of the down-regulated pathways can be made to CMI. The neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction pathway that participates in environmental information processing was significantly down-regulated in these three strains. The down-regulation of calcium signaling pathway in all strains may be related to depressed control of fast cellular processes. A large number of genes (46) in the metabolic pathways were uniquely down-regulated in ΔclpB (Table 4). Interestingly, 21 genes in the aforementioned pathway were significantly up-regulated in ΔlpcC (Supplementary Table S3), indicating opposite metabolic process effects of these two vaccines.

Table 3.

Participation of up-regulated genes in KEGG pathways in the three vaccine strains that protect against ID challenge with SCHU S4 challenge.

| KEGG Pathway ID | KEGG Pathway Name | Total Known Genes | ΔclpB Alone | ΔclpB and LVS Shared | ΔclpB, LVS and ΔgplX Shared | Total Gene Counts a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| padj | Matched Genes | padj | Matched Genes | padj | Matched Genes | ||||

| mmu04060 | Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction | 292 | 3.98 × 10−8 | Ccr1, Il21, Cx3cl1, Cd70, Cxcr1, Il17f, Il23a, Osmr, Tnfrsf8, Tnfsf9, Tnfrsf1b, Ccl11, Ccl22, Ccl9, Ccl6, Fasl, Ccl3, Il23r, Ccr8, Fas, Gdf15, Ltbr, Cxcl16 | 1.15 × 10−14 | Il10, Il11, Il33, Il13, Il12b, Il2ra, Ccl17, Il15ra, Tnf, Tnfsf15, Bmp10, Csf2rb2, Ccl8, Tnfrsf1a, Csf2rb, Tnfrsf11b, Ccl4, Il1f9, Cxcl1, Ccr5, Cxcl2, Cxcl5, Il12rb2, Lif, Tnfsf10, Il17a, Ccl24, Il1a, Tnfrsf9, Il1b, Il1r2, Xcl1, Inhba, Tnfrsf12a, Inhbb, Csf2, Csf3 | 5.75 × 10−6 | Cxcl11, Il12rb1, Il22, Cxcl10, Il27, Il6, Ccl12, Cxcl9, Ccl7, Ifng, Ccl2, Il1rn, Cxcl3 | 73 |

| mmu04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 211 | 3.29 × 10−5 | Jun, Pycard, Nlrp3, Nod2, Nod1, Mefv, Nlrp1b, Myd88, Tnf, Ifi207, Ifi206, Ifi204, Ripk3, Cybb, Il1b, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Tlr4 | 1.16 × 10−14 | Txn1, Gbp5, Mapk13, Gbp7, Nampt, Nlrp1a, Oas1g, Il6, Ccl12, Gbp2b, Oas2, Oas1a, Irf7, Ccl2, Stat2, Stat1, Gbp2, Cxcl3, Gbp4, Gbp3 | 38 | ||

| mmu04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 192 | 7.03 × 10−4 | Ccr1, Hck, Ccl11, Ccl22, Ccl9, Cx3cl1, Ccl6, Cxcr1, Ccl3, Ccr8, Cxcl16, Gng12 | 9.03 × 10−3 | Ccl24, Ccl8, Ccl4, Gnb4, Stat3, Pik3r6, Xcl1, Cxcl1, Ccl17, Ccr5, Cxcl2, Cxcl5 | 1.19 × 10−4 | Cxcl11, Ccl12, Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Ccl7, Ccl2, Stat2, Stat1, Cxcl3 | 33 |

| mmu04612 | Antigen processing and presentation | 90 | 1.06 × 10−4 | H2-T24, Psme2b, Ctss, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Lgmn, H2-T3, H2-Q1, Hsp90aa1 | 2.23 × 10−7 | H2-T23, H2-T10, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Hspa1b, Tap2, Hspa1a, H2-Q2, Psme1, Tnf, Hspa8, Gm11127, Tapbp, B2m | 0.01 | H2-T22, Ifng, Tap1, Psme2 | 27 |

| mmu04514 | Cell adhesion molecules | 174 | 7.15 × 10−5 | H2-T24, Sdc4, H2-K1, Ctla4, H2-Q4, Pdcd1, H2-T3, Tigit, H2-Q1, Nectin2, Selp, Mag, Cldn1 | 1.44 × 10−3 | H2-T23, H2-T10, H2-Q6, Sdc3, H2-Q7, H2-Q2, Nrcam, Pdcd1lg2, Itgam, Vcan, Ocln, Gm11127, Icam1 | 26 | ||

| mmu04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 93 | 3.32 × 10−3 | C1rb, C6, F13a1, Plat, Bdkrb1, Plaur, C2 | 6.68 × 10−9 | C1qb, Procr, C1ra, F10, Serping1, C5ar1, C3, F7, C1s2, Itgam, C1s1, Plau, C3ar1, Serpine1, A2m, Cfb | 23 | ||

| mmu04940 | Type I diabetes mellitus | 70 | 1.40 × 10−5 | H2-T24, Fasl, Ptprn, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Fas, Prf1, H2-T3, H2-Q1 | 4.11 × 10−6 | H2-T23, Il1a, H2-T10, Gm11127, H2-Q6, Il1b, H2-Q7, Il12b, H2-Q2, Tnf, Hspd1 | 0.03 | H2-T22, Ifng, Gzmb | 23 |

| mmu04630 | JAK-STAT signaling pathway | 168 | 2.37 × 10−5 | Il10, Il11, Socs3, Il12rb2, Il13, Il12b, Il2ra, Lif, Il15ra, Csf2rb2, Csf2rb, Myc, Stat3, Cdkn1a, Csf2, Csf3 | 1.41 × 10−3 | Il12rb1, Socs1, Il22, Il6, Ifng, Stat2, Stat1 | 23 | ||

| mmu04210 | Apoptosis | 136 | 1.29 × 10−4 | Ctss, Ctsd, Gadd45g, Fasl, Ctsz, Gadd45b, Fas, Prf1, Casp12, Bcl2a1b, Bcl2a1a | 1.76 × 10−3 | Ctsc, Csf2rb2, Jun, Tnfrsf1a, Csf2rb, Cycs, Fos, Daxx, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Tuba8 | 22 | ||

| mmu04620 | Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 100 | 4.97 × 10−3 | Ccl3, Tlr8, Tlr7, Cd14, Ikbke, Tlr3, Tlr2 | 7.77 × 10−3 | Jun, Il1b, Ccl4, Il12b, Fos, Myd88, Tlr4, Tnf | 5.88 × 10−5 | Cxcl11, Mapk13, Il6, Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Irf7, Stat1 | 22 |

| mmu05332 | Graft-versus-host disease | 63 | 4.67 × 10−5 | H2-T24, Fasl, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Fas, Prf1, H2-T3, H2-Q1 | 6.84 × 10−5 | H2-T23, Il1a, H2-T10, Gm11127, H2-Q6, Il1b, H2-Q7, H2-Q2, Tnf | 3.54 × 10−3 | H2-T22, Il6, Ifng, Gzmb | 21 |

| mmu05330 | Allograft rejection | 63 | 4.67 × 10−5 | H2-T24, Fasl, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Fas, Prf1, H2-T3, H2-Q1 | 6.84 × 10−5 | Il10, H2-T23, H2-T10, Gm11127, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Il12b, H2-Q2, Tnf | 0.02 | H2-T22, Ifng, Gzmb | 20 |

| mmu04650 | Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 121 | 9.74 × 10−4 | Raet1e, Klra7, Fasl, Sh2d1b2, H2-K1, Fas, Prf1, Ulbp1, Lcp2 | 0.02 | H2-T23, Raet1d, Klrk1, Fcer1g, Icam1, Csf2, Tnf, Tnfsf10 | 17 | ||

| mmu04640 | Hematopoietic cell lineage | 94 | 0.05 | Cd1d2, Sco1, Cd38, Cd14, Cd44 | 7.16 × 10−5 | Il11, Il1a, Itgam, Il1b, Il1r2, Il2ra, Anpep, Itga5, Csf2, Csf3, Tnf | 16 | ||

| mmu05320 | Autoimmune thyroid disease | 79 | 3.77 × 10−5 | H2-T24, Fasl, H2-K1, Ctla4, H2-Q4, Fas, Prf1, H2-T3, H2-Q1 | 7.28 × 10−3 | Il10, H2-T23, H2-T10, Gm11127, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, H2-Q2 | 16 | ||

| mmu05416 | Viral myocarditis | 88 | 0.01 | H2-T24, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Prf1, H2-T3, H2-Q1 | 3.59 × 10−3 | H2-T23, H2-T10, Gm11127, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Icam1, H2-Q2 | 14 | ||

| mmu00010 | Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 67 | 2.64 × 10−6 | Aldh1b1, Pkm, Tpi1, Ldha, Eno1b, Pgk1, Pgam1, Eno1, Gapdh, Hk2, Pfkp | 11 | ||||

| mmu04623 | Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 63 | 0.03 | Il33, Pycard, Ripk3, Il1b, Ccl4 | 3.60 × 10−5 | Il6, Cxcl10, Zbp1, Cgas, Irf7, Ifi202b | 11 | ||

| mmu03050 | Proteasome | 47 | 0.01 | Pomp, Psmb2, Psme1, Psma8, Psmb8 | 9.78 × 10−5 | Psma5, Ifng, Psme2, Psmb10, Psmb9 | 10 | ||

| mmu05133 | Pertussis | 77 | 0.02 | C1rb, Casp1, Cd14, Il23a, C2 | 1.11 × 10−16 | C1qb, Il10, C1ra, Jun, Pycard, Serping1, Nos2, Il12b, Itga5, Nlrp3, Fos, Nod1, Myd88, Tnf, C3, Il1a, C1s2, Itgam, C1s1, Il1b, Tlr4, Cxcl5 | 7.23 × 10−3 | Casp7, Mapk13, Il6, Irf1 | 31 |

| mmu05134 | Legionellosis | 61 | 0.04 | Bnip3, Casp1, Cd14, Tlr2 | 1.02 × 10−10 | Pycard, Cycs, Hspa1b, Il12b, Hspa1a, Myd88, Tnf, C3, Hspa8, Itgam, Il1b, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Tlr4, Hspd1 | 0.02 | Casp7, Il6, Cxcl3 | 22 |

| mmu05321 | Inflammatory bowel disease | 62 | 9.51 × 10−3 | Il21, Il23r, Il17f, Il23a, Tlr2 | 1.41 × 10−7 | Il10, Il1a, Jun, Il12rb2, Il1b, Il13, Il12b, Stat3, Nod2, Tlr4, Tnf, Il17a | 3.67 × 10−4 | Il12rb1, Il22, Il6, Ifng, Stat1 | 22 |

| mmu04657 | IL-17 signaling pathway | 91 | 6.22 × 10−4 | Ccl11, Il17f, Ikbke, Tnfaip3, S100a9, S100a8, Hsp90aa1, Lcn2 | 2.57 × 10−7 | Jun, Il13, Mmp3, Fos, Ccl17, Cebpb, Tnf, Il17a, Il1b, Cxcl1, Csf2, Cxcl2, Csf3, Cxcl5 | 1.95 × 10−8 | Mapk13, Il6, Mmp13, Ccl12, Cxcl10, Ccl7, Ifng, Ccl2, Cxcl3, Ptgs2 | 32 |

| mmu04061 | Viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor | 95 | 4.35 × 10−6 | Ccr1, Tnfrsf1b, Ccl11, Ccl22, Ccl9, Cx3cl1, Ccl6, Cxcr1, Ccl3, Ccr8, Ltbr | 4.45 × 10−7 | Il10, Il2ra, Ccl17, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Ccl24, Ccl8, Tnfrsf1a, Ccl4, Xcl1, Cxcl1, Ccr5, Cxcl2, Cxcl5 | 4.30 × 10−6 | Cxcl11, Il6, Ccl12, Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Ccl7, Ccl2, Cxcl3 | 33 |

| mmu04668 | TNF signaling pathway | 113 | 9.56 × 10−3 | Tnfrsf1b, Cx3cl1, Mmp14, Creb3l3, Fas, Creb3l1, Tnfaip3 | 2.68 × 10−9 | Jun, Socs3, Mmp3, Lif, Nod2, Fos, Creb5, Cebpb, Tnf, Tnfrsf1a, Ripk3, Il1b, Bcl3, Icam1, Cxcl1, Csf2, Cxcl2, Cxcl5 | 9.97 × 10−10 | Casp7, Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Cxcl10, Gm5431, Mlkl, Irf1, Ccl2, Ifi47, Cxcl3, Ptgs2 | 37 |

| mmu05146 | Amoebiasis | 107 | 3.97 × 10−4 | Cd1d2, Col3a1, Arg2, Col1a1, Gnal, Col4a2, Cd14, Serpinb6b, Tlr2 | 5.31 × 10−8 | Il10, Arg1, Nos2, Col4a1, Prdx1, Il12b, Tnf, Itgam, Il1b, Serpinb9, Il1r2, Cxcl1, Lamc2, Csf2, Cxcl2, Tlr4 | 4.24 × 10−3 | Serpinb9b, Il6, Ifng, Ctsg, Cxcl3 | 30 |

| mmu05323 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 87 | 0.04 | Atp6v1a, Ccl3, Ctla4, Il23a, Tlr2 | 1.44 × 10−7 | Il11, Jun, Mmp3, Fos, Tnf, Il17a, Il1a, Il1b, Icam1, Cxcl1, Csf2, Cxcl2, Tlr4, Cxcl5 | 1.72 × 10−3 | Il6, Ccl12, Ifng, Ccl2, Cxcl3 | 24 |

| mmu05140 | Leishmaniasis | 70 | 7.96 × 10−9 | Il10, Jun, Fcgr3, Nos2, Il12b, Fos, Myd88, Tnf, C3, Il1a, Itgam, Cybb, Il1b, Tlr4 | 6.45 × 10−4 | Fcgr1, Mapk13, Ifng, Stat1, Ptgs2 | 19 | ||

| mmu05144 | Malaria | 57 | 4.88 × 10−7 | Il10, Klrb1b, Klrk1, Hgf, Il1b, Icam1, Csf3, Myd88, Tlr4, Tnf, Thbs4 | 2.46 × 10−3 | Il6, Ccl12, Ifng, Ccl2 | 15 | ||

| mmu05143 | African trypanosomiasis | 39 | 8.73 × 10−3 | Fasl, Fas, Ido2, Ido1 | 7.65 × 10−4 | Il10, Il1b, Icam1, Il12b, Myd88, Tnf | 10 | ||

| mmu04625 | C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway | 112 | 0.03 | Ccl22, Egr2, Card9, Casp1, Il23a, Ikbke | 8.09 × 10−5 | Il10, Clec4d, Jun, Pycard, Fcer1g, Il1b, Bcl3, Clec7a, Il12b, Nlrp3, Ccl17, Tnf | 1.21 × 10−4 | Mapk13, Il6, Irf1, Stat2, Stat1, Clec4e, Ptgs2 | 25 |

| mmu05167 | Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection | 225 | 2.73 × 10−3 | Ccr1, H2-T24, Hck, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Ccr8, Fas, H2-T3, Ikbke, Gng12, H2-Q1, Tlr3 |

2.35 × 10−8 | H2-T23, Jun, H2-T10, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, H2-Q2, Fos, Cd200r4, C3, Hif1a, Rcn1, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Myc, Gnb4, Icam1, Stat3, Pik3r6, Cxcl1, Ccr5, Cdkn1a, Csf2, Cxcl2 |

7.64 × 10−5 | Mapk13, H2-T22, Il6, Eif2ak2, Irf7, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1, Cxcl3, Ptgs2 | 46 |

| mmu04145 | Phagosome | 182 | 4.35 × 10−4 | H2-T24, C1rb, Ctss, Lox, Atp6v1a, Lamp2, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Cd14, H2-T3, H2-Q1, Tlr2 | 1.01 × 10−6 | H2-T23, C1ra, Fcgr3, H2-T10, Tubb6, H2-Q6, Clec7a, H2-Q7, Tap2, H2-Q2, Itga5, Tuba8, C3, Itgam, Gm11127, Cybb, Olr1, Tlr4, Thbs4 | 9.58 × 10−3 | Fcgr1, Msr1, H2-T22, Tubb3, Tap1, Mpo | 37 |

| mmu05171 | Coronavirus disease—COVID-19 | 247 | 2.06 × 10−3 | C1rb, Sting1, F13a1, Casp1, Ikbke, Hbegf, C2, Selp, C6, Tlr8, Tlr7, Tlr3, Tlr2 | 3.40 × 10−8 | C1qb, Mx2, C5ar1, Mx1, Il12b, Tnf, C3, Tnfrsf1a, C3ar1, Ifih1, C1ra, Jun, Mmp3, Nlrp3, Fos, Myd88, C1s2, C1s1, Cybb, Il1b, Stat3, Csf2, Csf3, Tlr4, Cfb | 5.61 × 10−6 | Oas1g, Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Cxcl10, Oas2, Cgas, Oas1a, Eif2ak2, Ccl2, Stat2, Stat1 | 50 |

| mmu00220 | Arginine biosynthesis | 20 | 2.22 × 10−3 | Arg1, Got1, Nos2, Ass1 | 4 | ||||

| mmu00770 | Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 20 | 2.22 × 10−3 | Aldh1b1, Vnn3, Dpys, Bcat1 | 4 | ||||

| mmu00524 | Neomycin, kanamycin and gentamicin biosynthesis | 5 | 0.05 | Hk3 | 1 | ||||

| mmu05417 | Lipid and atherosclerosis | 216 | 5.74 × 10−3 | Selp, Ero1a, Lox, Fasl, Ccl3, Fas, Casp1, Cd14, Ikbke, Hsp90aa1, Tlr2 | 1.05 × 10−8 | Jun, Pycard, Cycs, Mmp3, Hspa1b, Il12b, Hspa1a, Nlrp3, Fos, Myd88, Sod2, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Hspa8, Tnfrsf1a, Cybb, Il1b, Icam1, Stat3, Olr1, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Tlr4, Hspd1 | 5.72 × 10−3 | Casp7, Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Irf7, Ccl2, Cxcl3 | 42 |

| mmu05169 | Epstein-Barr virus infection | 231 | 3.38 × 10−3 | H2-T24, Gadd45g, H2-K1, Gadd45b, H2-Q4, Fas, H2-T3, Ikbke, Tnfaip3, H2-Q1, Cd44, Tlr2 | 1.07 × 10−4 | H2-T23, Jun, H2-T10, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Tap2, H2-Q2, Myd88, Tnf, Gm11127, Myc, Icam1, Stat3, Vim, Cdkn1a, Tapbp, B2m |

4.16 × 10−7 | Mapk13, H2-T22, Cxcl10, Eif2ak2, Tap1, Oas1g, Il6, Oas2, Oas1a, Irf7, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1 | 43 |

| mmu05145 | Toxoplasmosis | 110 | 4.83 × 10−7 | Il10, Nos2, Cycs, Hspa1b, Il12b, Hspa1a, Myd88, Tnf, Hspa8, Tnfrsf1a, Stat3, Pik3r6, Lamc2, Ccr5, Tlr4 | 4.77 × 10−3 | Socs1, Mapk13, Ifng, Irgm1, Stat1 | 20 | ||

| mmu05142 | Chagas disease | 103 | 6.84 × 10−6 | C1qb, Il10, Jun, Nos2, Il12b, Fos, Myd88, Tnf, C3, Tnfrsf1a, Il1b, Serpine1, Tlr4 | 3.61 × 10−3 | Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Ifng, Ccl2 | 18 | ||

| mmu05164 | Influenza A | 173 | 8.65 × 10−6 | Ifih1, Il33, Pycard, Socs3, Cycs, Mx2, Mx1, Il12b, Nlrp3, Myd88, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Il1a, Tnfrsf1a, Il1b, Icam1, Tlr4 | 1.37 × 10−8 | Cxcl10, Eif2ak2, Oas1g, Il6, Ccl12, Ifng, Oas2, Oas1a, Irf7, Ccl2, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1 | 30 | ||

| mmu05163 | Human cytomegalovirus infection | 256 | 9.67 × 10−4 | Ccr1, H2-T24, Cx3cl1, Sting1, H2-K1, Creb3l3, H2-Q4, Creb3l1, H2-T3, H2-Q1, Fasl, Ccl3, Fas, Gng12 |

1.31 × 10−5 | H2-T23, H2-T10, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Tap2, H2-Q2, Creb5, Tnf, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Il1b, Myc, Ccl4, Gnb4, Stat3, Cdkn2a, Ccr5, Cdkn1a, Tapbp, B2m | 9.89 × 10−4 | Mapk13, H2-T22, Il6, Ccl12, Cgas, Ccl2, Tap1, Bak1, Ptgs2 | 44 |

| mmu05162 | Measles | 146 | 3.92 × 10−6 | Ifih1, Jun, Cycs, Mx2, Mx1, Hspa1b, Il12b, Il2ra, Hspa1a, Fos, Myd88, Hspa8, Il1a, Il1b, Stat3, Tlr4 | 1.38 × 10−5 | Oas1g, Il6, Oas2, Oas1a, Eif2ak2, Irf7, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1 | 25 | ||

| mmu04064 | NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 105 | 6.47 × 10−3 | Gadd45g, Gadd45b, Cd14, Ltbr, Tnfaip3, Bcl2a1b, Bcl2a1a | 8.17 × 10−4 | Tnfrsf1a, Plau, Il1b, Ccl4, Icam1, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Myd88, Tlr4, Tnf | 17 | ||

| mmu05310 | Asthma | 25 | 5.17 × 10−3 | Il10, Fcer1g, Il13, Tnf | 4 | ||||

| mmu04217 | Necroptosis | 174 | 0.03 | Fasl, Fth1, Chmp4b, Fas, Casp1, Tnfaip3, Tlr3, Hsp90aa1 | 1.44 × 10−3 | Il33, Pycard, Nlrp3, Pla2g4a, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Il1a, Tnfrsf1a, Ripk3, Cybb, Il1b, Stat3, Tlr4 | 7.76 × 10−3 | Zbp1, Ifng, Mlkl, Eif2ak2, Stat2, Stat1 | 27 |

| mmu05170 | Human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection | 240 | 0.01 | H2-T24, Tnfrsf1b, Fasl, Sting1, H2-K1, H2-Q4, Fas, H2-T3, Gng12, H2-Q1, Tlr2 | 1.68 × 10−5 | H2-T23, Jun, H2-T10, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Tap2, H2-Q2, Fos, Myd88, Tnf, Bst2, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Gnb4, Samhd1, Ccr5, Tapbp, B2m, Tlr4 |

0.03 | Mapk13, H2-T22, Cgas, Trim30d, Tap1, Bak1 | 37 |

| mmu05161 | Hepatitis B | 163 | 7.29 × 10−3 | Egr2, Fasl, Creb3l3, Fas, Creb3l1, Ikbke, Casp12, Tlr3, Tlr2 | 7.05 × 10−3 | Ifih1, Jun, Cycs, Myc, Stat3, Fos, Cdkn1a, Creb5, Myd88, Tlr4, Tnf | 0.02 | Mapk13, Il6, Irf7, Stat2, Stat1 | 25 |

| mmu01230 | Biosynthesis of amino acids | 79 | 2.16 × 10−6 | Pkm, Tpi1, Arg1, Got1, Eno1b, Pgk1, Pgam1, Eno1, Gapdh, Bcat1, Pfkp, Ass1 | 12 | ||||

| mmu05160 | Hepatitis C | 165 | 8.80 × 10−4 | Socs3, Cycs, Ifit1bl1, Mx2, Mx1, Nr1h3, Tnf, Ywhag, Ocln, Tnfrsf1a, Myc, Stat3, Cdkn1a | 7.48 × 10−8 | Oas1g, Cxcl10, Ifng, Oas2, Oas1a, Ifit1bl2, Eif2ak2, Irf7, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1, Ifit1 | 25 | ||

| mmu05235 | PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer | 88 | 3.59 × 10−3 | Hif1a, Jun, Stat3, Fos, Batf3, Myd88, Tlr4, Batf | 1.81 × 10−3 | Cd274, Mapk13, Ifng, Stat1, Batf2 | 13 | ||

| mmu04380 | Osteoclast differentiation | 128 | 2.90 × 10−4 | Il1a, Lilrb4a, Jun, Sirpb1a, Socs3, Fcgr3, Tnfrsf1a, Tnfrsf11b, Il1b, Fos, Tnf, Fosl2 | 1.71 × 10−3 | Socs1, Fcgr1, Mapk13, Ifng, Stat2, Stat1 | 18 | ||

| mmu05152 | Tuberculosis | 180 | 8.51 × 10−7 | Il10, Fcgr3, Nos2, Vdr, Cycs, Clec7a, Il12b, Nod2, Cebpb, Myd88, Tnf, C3, Il1a, Itgam, Tnfrsf1a, Fcer1g, Il1b, Tlr4, Hspd1 | 9.10 × 10−3 | Fcgr1, Mapk13, Il6, Ifng, Stat1, Clec4e | 25 | ||

| mmu04933 | AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 101 | 2.35 × 10−3 | Il1a, Jun, Col4a1, Cybb, Il1b, Icam1, Stat3, Serpine1, Tnf | 3.31 × 10−3 | Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Ccl2, Stat1 | 14 | ||

| mmu04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 114 | 7.73 × 10−7 | Nos2, Eno1b, Timp1, Eno1, Gapdh, Hk2, Hif1a, Ldha, Cybb, Pgk1, Stat3, Serpine1, Cdkn1a, Tlr4, Pfkp | 15 | ||||

| mmu04659 | Th17 cell differentiation | 104 | 0.03 | Hif1a, Jun, Il1b, Il2ra, Stat3, Fos, Il17a | 5.80 × 10−4 | Il12rb1, Il22, Mapk13, Il6, Ifng, Stat1 | 13 | ||

| mmu05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 124 | 2.29 × 10−6 | C1qb, Il10, C1ra, Fcgr3, Krt14, C5ar1, Fpr1, C3, C1s2, Itgam, C1s1, Ptafr, C3ar1, Icam1, Cfb | 15 | ||||

| mmu05230 | Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 69 | 7.45 × 10−4 | Hif1a, Pkm, Ldha, Myc, Pgam1, Slc16a3, Hk2, Pfkp | 8 | ||||

| mmu04658 | Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation | 88 | 0.04 | Jun, Il12rb2, Il13, Il12b, Il2ra, Fos | 0.01 | Il12rb1, Mapk13, Ifng, Stat1 | 10 | ||

| mmu05203 | Viral carcinogenesis | 229 | 8.77 × 10−3 | H2-T24, Egr2, Scin, H2-K1, Creb3l3, H2-Q4, Ccr8, Creb3l1, H2-T3, Ltbr, H2-Q1 | 2.36 × 10−3 | H2-T23, Jun, H2-T10, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, H2-Q2, Creb5, Ywhag, C3, Pkm, Gm11127, Stat3, Cdkn2a, Ccr5, Cdkn1a | 26 | ||

| mmu05165 | Human papillomavirus infection | 362 | 0.02 | H2-T24, Col1a1, Atp6v1a, Col4a2, H2-K1, Creb3l3, H2-Q4, Creb3l1, H2-T3, Ikbke, H2-Q1, Fasl, Fas, Tlr3 |

7.78 × 10−3 | H2-T23, H2-T10, Col4a1, Fzd7, H2-Q6, Mx2, H2-Q7, Mx1, Tnc, H2-Q2, Itga5, Creb5, Tnf, Pkm, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Lamc2, Cdkn1a, Thbs4 | 0.03 | Oasl1, H2-T22, Irf1, Eif2ak2, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1, Ptgs2 | 41 |

| mmu05135 | Yersinia infection | 134 | 1.56 × 10−3 | Il10, Jun, Pycard, Il1b, Itga5, Nlrp3, Fos, Mefv, Myd88, Tlr4, Tnf | 0.04 | Mapk13, Il6, Ccl12, Ccl2 | 15 | ||

| mmu00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 54 | 4.24 × 10−3 | Aldh1b1, Gatm, Arg1, Got1, Nos2, Cndp2 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04930 | Type II diabetes mellitus | 48 | 0.01 | Socs3, Pkm, Hpca, Tnf, Hk2 | 5 | ||||

| mmu05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 205 | 0.03 | Col1a1, Fasl, Sdc4, Fas, Plaur, Met, Cd44, Hbegf, Tlr2 | 0.01 | Hif1a, Plau, Fzd7, Hgf, Myc, Hpse, Il12b, Stat3, Itga5, Cdkn1a, Tlr4, Tnf | 21 | ||

| mmu05418 | Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis | 148 | 9.91 × 10−3 | Il1a, Jun, Tnfrsf1a, Il1b, Icam1, Il1r2, Fos, Mgst1, Tnf, Ass1 | 0.02 | Txn1, Mapk13, Ccl12, Ifng, Ccl2 | 15 | ||

| mmu04216 | Ferroptosis | 40 | 9.54 × 10−3 | Fth1, Slc39a14, Slc39a1, Cp | 4 | ||||

| mmu05132 | Salmonella infection | 253 | 9.31 × 10−4 | Jun, Pycard, Tubb6, Cycs, Nlrp3, Fos, Nod1, Gapdh, Myd88, Tnf, Tnfsf10, Tuba8, Tnfrsf1a, Ripk3, Il1b, Myc, Tlr4 | 0.01 | Txn1, Casp7, Mapk13, Il6, Mlkl, Tubb3, Bak1 | 24 | ||

| mmu05166 | Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection | 247 | 7.53 × 10−6 | H2-T23, Jun, H2-T10, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Il2ra, H2-Q2, Fos, Creb5, Il15ra, Tnf, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Myc, Icam1, Il1r2, Tspo, Cdkn2a, Cdkn1a, Csf2, B2m | 21 | ||||

| mmu01200 | Carbon metabolism | 122 | 2.55 × 10−3 | Pkm, Tpi1, Got1, Eno1b, Pgk1, Pgam1, Eno1, Gapdh, Hk2, Pfkp | 10 | ||||

| mmu05210 | Colorectal cancer | 88 | 0.01 | Jun, Cycs, Myc, Mcub, Fos, Cdkn1a, Ralgds | 7 | ||||

| mmu05168 | Herpes simplex virus 1 infection | 458 | 0.02 | H2-T23, Ifih1, Socs3, H2-T10, Cycs, H2-Q6, H2-Q7, Il12b, Tap2, H2-Q2, Itga5, Myd88, Tnf, Bst2, C3, Tnfrsf1a, Gm11127, Il1b, Tapbp, B2m, Daxx |

4.15 × 10−5 | H2-T22, Eif2ak2, Tap1, Oas1g, Il6, Ccl12, Ifng, Oas2, Cgas, Oas1a, Irf7, Ccl2, Stat2, Bak1, Stat1 | 36 | ||

| mmu04664 | Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 66 | 0.04 | Fcer1g, Il13, Pla2g4a, Csf2, Tnf | 5 | ||||

| mmu01524 | Platinum drug resistance | 80 | 0.03 | Slc31a1, Cycs, Cdkn2a, Mgst1, Cdkn1a, Atp7a | 6 | ||||

| mmu04978 | Mineral absorption | 54 | 0.03 | Slc6a19, Fth1, Slc39a1, Steap2 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04931 | Insulin resistance | 110 | 0.01 | Ptpn1, Socs3, Tnfrsf1a, Nr1h3, Stat3, Ppargc1b, Creb5, Tnf | 8 | ||||

| mmu05231 | Choline metabolism in cancer | 98 | 0.02 | Hif1a, Jun, Slc44a5, Pdgfc, Pla2g4a, Fos, Ralgds | 7 | ||||

| mmu05221 | Acute myeloid leukemia | 70 | 0.05 | Itgam, Myc, Stat3, Cebpe, Csf2 | 5 | ||||

| mmu04146 | Peroxisome | 86 | 0.04 | Prdx5, Nos2, Prdx1, Hp, Sod2, Xdh | 6 | ||||

| mmu04932 | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 151 | 0.01 | Il1a, Jun, Socs3, Tnfrsf1a, Cycs, Il1b, Nr1h3, Cox4i2, Fos, Tnf | 10 | ||||

| mmu05222 | Small cell lung cancer | 93 | 0.05 | Nos2, Col4a1, Cycs, Myc, Lamc2, Cdkn1a | 6 | ||||

| mmu00052 | Galactose metabolism | 32 | 0.04 | Hk3, Mgam | 2 | ||||

| mmu04215 | Apoptosis—multiple species | 32 | 0.04 | Casp7, Bak1 | 2 | ||||

| mmu04010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 294 | 1.91 × 10−3 | Jun, Cacna1f, Hpca, Hgf, Pdgfc, Mcub, Hspa1b, Hspa1a, Pla2g4a, Fos, Myd88, Tnf, Hspa8, Il1a, Tnfrsf1a, Il1b, Myc, Daxx | 18 | ||||

| mmu05322 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 148 | 0.03 | C1qb, C3, Il10, C1ra, C1s2, C1s1, Tnf, Elane, Trim21 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04916 | Melanogenesis | 100 | 0.02 | AC117663.3, Sco1, Creb3l3, Creb3l1, Mitf, AC110211.1 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04218 | Cellular senescence | 184 | 0.02 | H2-T23, Il1a, H2-T10, Gm11127, H2-Q6, Myc, H2-Q7, H2-Q2, Serpine1, Cdkn2a, Cdkn1a | 11 | ||||

| mmu05020 | Prion disease | 268 | 4.31 × 10−3 | C1qb, Cacna1f, Tubb6, Cycs, Psmb2, Hspa1b, Hspa1a, Creb5, Tnf, Tuba8, Hspa8, Il1a, Cybb, Il1b, Cox4i2, Psma8 | 16 | ||||

| mmu00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 34 | 0.05 | Hk3, Mgam | 2 | ||||

| mmu04917 | Prolactin signaling pathway | 74 | 6.29 × 10−3 | Socs1, Mapk13, Irf1, Stat1 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04142 | Lysosome | 131 | 0.02 | Slc11a1, Ctss, Ctsd, Npc2, Lamp2, Ctsz, Lgmn | 7 | ||||

| mmu04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 359 | 0.03 | Col4a1, Hgf, Pdgfc, Mcub, Il2ra, Tnc, Itga5, Creb5, Ywhag, Myc, Gnb4, Pik3r6, Lamc2, Cdkn1a, Csf3, Tlr4, Thbs4 | 17 | ||||

| mmu04926 | Relaxin signaling pathway | 129 | 0.05 | Col3a1, Col1a1, Col4a2, Creb3l3, Creb3l1, Gng12 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04622 | RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | 70 | 0.03 | Mapk13, Cxcl10, Irf7 | 3 | ||||

| mmu05200 | Pathways in cancer | 543 | 0.04 | Jun, Il12rb2, Nos2, Col4a1, Cycs, Fzd7, Hgf, Il13, Il12b, Il2ra, Fos, Il15ra, Ralgds, Csf2rb2, Hif1a, Csf2rb, Myc, Gnb4, Stat3, Cdkn2a, Lamc2, Mgst1, Cdkn1a | 23 | ||||

| mmu05202 | Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 223 | 0.05 | Gadd45g, Gadd45b, Mitf, Plat, Cd14, Met, Nr4a3, Bcl2a1b, Bcl2a1a | 9 | ||||

a Genes identified from current study involved in stated pathway.

Table 4.

Participation of down-regulated genes in KEGG pathways in the three vaccine strains that protect against ID challenge against SCHU S4 challenge.

| KEGG Pathway ID | KEGG Pathway Name | Total Known Genes | ΔclpB Alone | ΔclpB and LVS Shared | ΔclpB, LVS and ΔgplX Shared | Total Gene Counts a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| padj | Matched Genes | padj | Matched Genes | padj | Matched Genes | ||||

| mmu04080 | Neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction | 358 | 2.69 × 10−5 | Gh, Ghrhr, Chrne, Gabrr2, Npff, Cnr1, Prss2, Lhcgr, Cort, Tshr, Gabra4, Vipr2, Gria2, Gal, Gria1, Sstr2, Chrna6, Grm6, P2rx2, Glp1r, Grik3, Tac2, S1pr5, Htr5b | 1.08 × 10−3 | Grin2a, Npb, Adra1b, Oxtr, Adra2b, Edn3, Ednrb, Npy1r, Aplnr, Gpr156, Vipr1, Ptgfr, Grm4, Gabbr1, Rxfp1, Lpar3 | 40 | ||

| mmu04020 | Calcium signaling pathway | 240 | 6.53 × 10−4 | Cacna1g, Atp2b2, Egf, Atp2a3, Fgf18, Plce1, Casq2, Fgfr4, Lhcgr, Plcd3, Camk2b, Pln, P2rx2, Adcy2, Mylk3, Htr5b | 1.59 × 10−4 | Grin2a, Ryr2, Adra1b, Oxtr, Ednrb, Cacna1b, Fgfr3, Fgfr2, Prkcg, Ntrk2, Ptgfr, Camk2a, Ntrk3, Cacna1i | 30 | ||

| mmu05414 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 94 | 8.52 × 10−4 | Tro, Tnnt2, Pln, Sgca, Atp2a3, Itga8, Adcy2, Sgcg, Ttn | 8.30 × 10−3 | Ryr2, Itga11, Tgfb2, Adcy5, Cacna2d4, Cacng3 | 15 | ||

| mmu04512 | ECM–receptor interaction | 88 | 8.81 × 10−3 | Frem2, Vtn, Reln, Tnxb, Col4a3, Col6a6, Itga8 | 1.27 × 10−3 | Itga11, Sv2b, Sv2a, Lama3, Col6a4, Fras1, Thbs3 | 14 | ||

| mmu05410 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 91 | 2.83 × 10−3 | Tro, Tnnt2, Sgca, Atp2a3, Prkag3, Itga8, Sgcg, Ttn | 7.12 × 10−3 | Ryr2, Itga11, Ace, Tgfb2, Cacna2d4, Cacng3 | 14 | ||

| mmu04916 | Melanogenesis | 100 | 0.02 | Camk2b, Fzd2, Gnao1, Hr, Adcy2, Wnt2, AC084822.1 | 0.01 | Prkcg, Ednrb, Camk2a, Fzd6, Wnt5b, Adcy5 | 13 | ||

| mmu05217 | Basal cell carcinoma | 63 | 0.03 | Fzd8, Gli1, Wnt10a, Wnt10b | 0.03 | Bmp4, Apc2, Fzd6, Wnt5b | 8 | ||

| mmu04950 | Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 27 | 6.39 × 10−4 | Bhlha15, Hnf1b, Nr5a2, Foxa2, Foxa3 | 5 | ||||

| mmu01100 | Metabolic pathways | 1573 | 9.01 × 10−4 | Rimkla, Aldh1a1, Pcx, Selenbp2, Gsta4, Ptdss2, Sec1, B3gnt3, Uros, Mgat3, Suox, Phospho1, Pcyt1b, Cers1, Dhtkd1, B4galnt3, Cox6a2, Hmbs, Mgst3, Hsd3b1, Hagh, Adcy1, Car8, Nags, Mgll, Nqo1, Car2, Gpx1, St3gal5, Pigq, Pik3c2b, Aspdh, Cel, Gck, Cox6b2, Cox8b, Fahd1, Hyal3, Pipox, Urod, Mboat2, Pnpo, Sgpp2, Pip5k1b, Acmsd, Trak2 | 46 | ||||

| mmu04260 | Cardiac muscle contraction | 87 | 1.19 × 10−3 | Myl4, Actc1, Cox6b2, Cox8b, Cox6a2, Cacng4, Trdn | 7 | ||||

| mmu00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 40 | 3.94 × 10−3 | Gamt, Alas2, Cbs, Gcat, Gnmt | 5 | ||||

| mmu04310 | Wnt signaling pathway | 168 | 4.27 × 10−3 | Apc2, Prkcg, Tle2, Camk2a, Fzd6, Sox17, Wnt5b, Cxxc4, Dkk2 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04514 | Cell adhesion molecules | 174 | 5.37 × 10−3 | Cldn13, Cadm3, Cd4, Cdh4, Cldn9, H2-M2, Cd8b1, Nrxn2, Vtcn1 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04722 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 121 | 7.58 × 10−3 | Mapk12, Ntrk2, Camk2a, Ntrk3, Ntf3, Mapk11, Matk | 7 | ||||

| mmu05412 | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 77 | 0.02 | Actn2, Cdh2, Sgca, Atp2a3, Itga8, Sgcg | 6 | ||||

| mmu00860 | Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | 43 | 0.05 | Hmbs, Uros, Urod | 3 | ||||

| mmu04360 | Axon guidance | 181 | 0.05 | Rac3, Syp, Efna4, Plxnb1, Prkcz, Sema4f, Myl9 | 0.05 | Epha4, Ablim2, Ephb6, Camk2b, Epha8, Hr, Ephb1, Bmp7, Sema4g | 6.92 × 10−3 | Efnb2, Camk2a, Ablim3, Sema6c, Wnt5b, Ntn4, Lrrc4c, L1cam, Rgma | 25 |

| mmu04024 | cAMP signaling pathway | 215 | 1.58×10−5 | Atp2b2, Npr1, Hhip, Atp2a3, Plce1, Lhcgr, Cnga2, Tshr, Cnga1, Vipr2, Ppp1r1b, Camk2b, Gria2, Gria1, Pln, Sstr2, Glp1r, Adcy2 | 0.02 | Grin2a, Ryr2, Oxtr, Edn3, Gabbr1, Camk2a, Fxyd1, Npy1r, Adcy5 | 27 | ||

| mmu04972 | Pancreatic secretion | 114 | 2.77 × 10−4 | Car2, Cckar, Cela3a, Prss1, Slc12a2, Adcy1, Cel, Slc26a3, Cpa1 | 0.01 | Atp2b2, Atp2a3, Kcnq1, Adcy2, Amy1, Ctrl, Prss2, Cpa2 | 17 | ||

| mmu04713 | Circadian entrainment | 98 | 0.05 | Cacna1g, Camk2b, Gria2, Gria1, Gnao1, Adcy2 | 8.67 × 10−5 | Grin2a, Ryr2, Gucy1a1, Prkcg, Camk2a, Gng8, Kcnj9, Adcy5, Cacna1i | 15 | ||

| mmu04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 108 | 0.02 | Cela3a, Prss1, Col14a1, Col4a6, Col8a2, Cpa1 | 5.78×10−4 | Col11a1, Col4a3, Col13a1, Eln, Col6a6, Kcnq1, Ctrl, Col19a1, Prss2, Cpa2 | 16 | ||

| mmu04727 | GABAergic synapse | 89 | 2.46×10−3 | Gabra4, Gls2, Slc12a5, Gabrr2, Gnao1, Slc38a3, Abat, Adcy2 | 6.40 × 10−3 | Prkcg, Gabbr1, Gad1, Cacna1b, Gng8, Adcy5 | 14 | ||

| mmu04724 | Glutamatergic synapse | 113 | 8.26 × 10−4 | Shank1, Gria2, Gria1, Homer2, Gls2, Grm6, Gnao1, Slc38a3, Adcy2, Grik3 | 0.02 | Grin2a, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Grm4, Gng8, Adcy5 | 16 | ||

| mmu04971 | Gastric acid secretion | 75 | 0.01 | Atp4a, Camk2b, Sstr2, Kcnq1, Adcy2, Mylk3 | 2.75 × 10−3 | Prkcg, Kcnj1, Camk2a, Kcnj16, Adcy5, Kcnf1 | 12 | ||

| mmu04911 | Insulin secretion | 86 | 0.02 | Cckar, Kcnn2, Adcy1, Gcg, Gck | 5.42 × 10−3 | Ryr2, Prkcg, Syt3, Camk2a, Ffar1, Adcy5 | 11 | ||

| mmu05200 | Pathways in cancer | 543 | 0.05 | Nqo1, Fbxo24, Gsta4, Ctnna3, Fzd8, Flt3l, Col4a6, Gli1, Mgst3, Notch3, Gnb3, Rac3, Adcy1, Wnt10a, Hes5, Wnt10b | 2.78 × 10−3 | Apc2, Hlf, Ednrb, Fzd6, Runx1t1, Fgfr3, Fgfr2, Bmp4, Prkcg, Heyl, Tgfb2, Hey2, Camk2a, Lama3, Hey1, Wnt5b, Gng8, Rxrg, Lpar3, Adcy5 | 36 | ||

| mmu04925 | Aldosterone synthesis and secretion | 102 | 0.05 | Cacna1g, Camk2b, Atp2b2, Npr1, Star, Adcy2 | 2.98 × 10−3 | Hsd3b6, Kcnk3, Prkcg, Cyp21a1, Camk2a, Adcy5, Cacna1i | 13 | ||

| mmu04261 | Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 152 | 0.05 | Tro, Tnnt2, Camk2b, Pln, Atp2b2, Atp2a3, Kcnq1, Adcy2 | 7.70 × 10−3 | Mapk12, Ryr2, Adra1b, Camk2a, Adcy5, Cacna2d4, Cacng3, Mapk11 | 16 | ||

| mmu04725 | Cholinergic synapse | 112 | 0.03 | Ache, Camk2b, Chrna6, Gnao1, Kcnq1, Hr, Adcy2 | 0.02 | Prkcg, Camk2a, Cacna1b, Gng8, Adcy5, Kcnf1 | 13 | ||

| mmu05031 | Amphetamine addiction | 69 | 0.04 | Ppp1r1b, Camk2b, Ddc, Gria2, Gria1 | 0.04 | Grin2a, Prkcg, Camk2a, Adcy5 | 9 | ||

| mmu05231 | Choline metabolism in cancer | 98 | 0.04 | Pcyt1b, Slc22a2, Wasf3, Rac3, Pip5k1b | 0.05 | Gpcpd1, Egf, Slc22a4, Dgkb, Hr, Chkb | 11 | ||

| mmu04350 | TGF-beta signaling pathway | 95 | 1.0 × 10−45 | Bmp4, Tgfb2, 4930516B21Rik, Nog, Id4, Smad9, Id3, Fmod, Rgma, Thsd4 | 10 | ||||

| mmu04550 | Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 140 | 1.15 × 10−5 | Bmp4, Mapk12, Apc2, 4930516B21Rik, Fzd6, Wnt5b, Id4, Smad9, Id3, Fgfr3, Fgfr2, Mapk11 | 12 | ||||

| mmu04921 | Oxytocin signaling pathway | 153 | 1.35 × 10−4 | Ryr2, Gucy1a1, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Oxtr, Camk2a, Kcnj9, Adcy5, Kcnf1, Cacna2d4, Cacng3 | 11 | ||||

| mmu04976 | Bile secretion | 100 | 5.54 × 10−4 | Car2, Kcnn2, Aqp9, Ephx1, Aqp8, Adcy1, Slc22a7, Aqp1 | 8 | ||||

| mmu04728 | Dopaminergic synapse | 135 | 9.55 × 10−4 | Grin2a, Mapk12, Prkcg, Camk2a, Cacna1b, Gng8, Kcnj9, Adcy5, Mapk11 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04640 | Hematopoietic cell lineage | 94 | 1.87 × 10−3 | Cd24a, Cd4, Cd59b, Tfrc, Cd8b1, Dntt, Flt3l | 7 | ||||

| mmu04934 | Cushing syndrome | 162 | 3.36 × 10−3 | Apc2, Hsd3b6, Kcnk3, Cyp21a1, Camk2a, Fzd6, Wnt5b, Adcy5, Cacna1i | 9 | ||||

| mmu04010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 294 | 3.48 × 10−3 | Mapk12, Pla2g4f, Cacna1b, Fgfr3, Cacng3, Fgfr2, Prkcg, Ntrk2, Tgfb2, Ntf3, Cacna1i, Cacna2d4, Mapk11 | 13 | ||||

| mmu05144 | Malaria | 57 | 3.89 × 10−3 | Gypa, Hbb-bh2, Hba-a1, Hbb-bt, Hbb-bs, Ackr1 | 6 | ||||

| mmu05033 | Nicotine addiction | 40 | 3.94 × 10−3 | Gabra4, Gria2, Gria1, Chrna6, Gabrr2 | 5 | ||||

| mmu00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 40 | 6.45 × 10−3 | Aoc3, Adh1, Aox4, Aox3 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04723 | Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling | 148 | 6.59 × 10−3 | Mapk12, Prkcg, Faah, Cacna1b, Gng8, Kcnj9, Adcy5, Mapk11 | 8 | ||||

| mmu05032 | Morphine addiction | 91 | 7.12 × 10−3 | Prkcg, Gabbr1, Cacna1b, Gng8, Kcnj9, Adcy5 | 6 | ||||

| mmu00514 | Other types of O-glycan biosynthesis | 43 | 8.33 × 10−3 | St6gal1, Colgalt2, Gxylt2, Galnt16 | 4 | ||||

| mmu00410 | beta-Alanine metabolism | 31 | 8.76 × 10−3 | Upb1, Aldh3a1, Aldh3b2, Abat | 4 | ||||

| mmu00750 | Vitamin B6 metabolism | 9 | 0.01 | Aox4, Aox3 | 2 | ||||

| mmu04924 | Renin secretion | 76 | 0.01 | Gucy1a1, Ace, Edn3, Adcy5, Kcnf1 | 5 | ||||

| mmu04927 | Cortisol synthesis and secretion | 72 | 0.01 | Hsd3b6, Kcnk3, Cyp21a1, Adcy5, Cacna1i | 5 | ||||

| mmu00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 23 | 0.02 | Ddc, Aldh3a1, Aldh3b2 | 3 | ||||

| mmu00920 | Sulfur metabolism | 11 | 0.02 | Selenbp2, Suox | 2 | ||||

| mmu04977 | Vitamin digestion and absorption | 24 | 0.02 | Slc23a1, Apoa4, Plb1 | 3 | ||||

| mmu05143 | African trypanosomiasis | 39 | 0.02 | Hbb-bh2, Hba-a1, Hbb-bt, Hbb-bs | 4 | ||||

| mmu04015 | Rap1 signaling pathway | 214 | 0.02 | Grin2a, Mapk12, Prkcg, Magi2, Fgfr3, Lpar3, Adcy5, Fgfr2, Mapk11 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04072 | Phospholipase D signaling pathway | 149 | 0.02 | Pla2g4f, Ptgfr, Grm4, Dgka, Lpar3, Adcy5, Dnm1 | 7 | ||||

| mmu04270 | Vascular smooth muscle contraction | 143 | 0.02 | Gucy1a1, Pla2g2d, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Adra1b, Edn3, Adcy5 | 7 | ||||

| mmu04370 | VEGF signaling pathway | 58 | 0.02 | Mapk12, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Mapk11 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04970 | Salivary secretion | 86 | 0.02 | Gucy1a1, Prkcg, Adra1b, Trpv6, Adcy5 | 5 | ||||

| mmu05152 | Tuberculosis | 180 | 0.02 | Cd209g, Mapk12, Cd209f, Tgfb2, Camk2a, Cd209a, Atp6v0a4, Mapk11 | 8 | ||||

| mmu05418 | Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis | 148 | 0.02 | Bmp4, Mapk12, Thbd, 4930516B21Rik, Klf2, Mapk11, Nox1 | 7 | ||||

| mmu04150 | mTOR signaling pathway | 156 | 0.03 | Rps6ka6, Stradb, Deptor, Fbxo24, Fzd8, Wnt10a, Wnt10b | 7 | ||||

| mmu04014 | Ras signaling pathway | 232 | 0.03 | Grin2a, Pla2g2d, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Ntrk2, Ntf3, Gng8, Fgfr3, Fgfr2 | 9 | ||||

| mmu04330 | Notch signaling pathway | 60 | 0.03 | Heyl, Tle2, Hey2, Hey1 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04390 | Hippo signaling pathway | 157 | 0.03 | Bmp4, Apc2, Tgfb2, Rassf6, Fzd6, Wnt5b, Ajuba | 7 | ||||

| mmu04750 | Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels | 127 | 0.03 | Mapk12, Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Camk2a, Adcy5, Mapk11 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04912 | GnRH signaling pathway | 90 | 0.03 | Mapk12, Pla2g4f, Camk2a, Adcy5, Mapk11 | 5 | ||||

| mmu04913 | Ovarian steroidogenesis | 63 | 0.03 | Hsd3b6, Pla2g4f, Cyp1a1, Adcy5 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04926 | Relaxin signaling pathway | 129 | 0.03 | Mapk12, Ednrb, Gng8, Rxfp1, Adcy5, Mapk11 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04929 | GnRH secretion | 63 | 0.03 | Prkcg, Gabbr1, Kcnj9, Cacna1i | 4 | ||||

| mmu04960 | Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption | 38 | 0.03 | Prkcg, Kcnj1, Sfn | 3 | ||||

| mmu00910 | Nitrogen metabolism | 17 | 0.04 | Car2, Car8 | 2 | ||||

| mmu04710 | Circadian rhythm | 30 | 0.04 | Npas2, Prkag3, Rorc | 3 | ||||

| mmu05135 | Yersinia infection | 134 | 0.04 | Cd4, Rps6ka6, Fbxo24, Cd8b1, Rac3, Pip5k1b | 6 | ||||

| mmu05218 | Melanoma | 72 | 0.04 | Egf, Fgf18, E2f2, Gadd45a, Hr | 5 | ||||

| mmu00250 | Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 39 | 0.04 | Gad1, Aldh5a1, Ddo | 3 | ||||

| mmu00760 | Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 41 | 0.04 | Aox4, Aox3, Nmnat2 | 3 | ||||

| mmu00830 | Retinol metabolism | 97 | 0.04 | Adh1, Aox4, Aox3, Cyp1a1, Lrat | 5 | ||||

| mmu00982 | Drug metabolism—cytochrome P450 | 71 | 0.04 | Adh1, Aox4, Aox3, Fmo2 | 4 | ||||

| mmu04726 | Serotonergic synapse | 131 | 0.04 | Pla2g4f, Prkcg, Cacna1b, Gng8, Kcnj9, Adcy5 | 6 | ||||

| mmu04933 | AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 101 | 0.04 | Mapk12, Thbd, Tgfb2, Mapk11, Nox1 | 5 | ||||

| mmu05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 205 | 0.04 | Mapk12, Prkcg, Tgfb2, Camk2a, Fzd6, Wnt5b, Gpc3, Mapk11 | 8 | ||||

| mmu00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 52 | 0.05 | Afmid, Ddc, Haao, Inmt | 4 | ||||

| mmu04918 | Thyroid hormone synthesis | 74 | 0.05 | Ttr, Adcy2, Duox2, Slc5a5, Tshr | 5 | ||||

| mmu05214 | Glioma | 74 | 0.05 | Camk2b, Egf, E2f2, Gadd45a, Hr | 5 | ||||

| mmu05225 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 174 | 0.05 | Nqo1, Gsta4, Mgst3, Dpf3, Fzd8, Wnt10a, Wnt10b | 7 | ||||

a Genes identified from current study involved in stated pathway.

Because biomarkers for vaccine strains that outperform LVS need to be robust, we have selected potential transcriptional changes (Table 5) that have to meet the following filtering criteria: (1) the transcripts are highly abundant (read count > 300, in up-regulated testing strain, or in naïve for down-regulation); (2) more than 4-fold changes (|log2FC| > 2) in ΔclpB versus naïve; (3) the gene products are known to be expressed in whole blood, either naturally or by secretion; (4) more than two fold changes in ΔclpB versus LVS, which could be sufficient to distinguish host responses to these functionally closely related vaccines. By these criteria, some of the genes ranked highly in Supplementary Table S1, failed to make the grade for inclusion in Table 5. In addition to their ability to distinguish ΔclpB from the others three test vaccines, a majority of these selected genes can be used to separate LVS from ΔgplX and ΔlpcC and some of them can also be used to distinguish ΔgplX from ΔlpcC (Supplementary Table S4). ΔlpcC was unable to protect against either respiratory or intradermal challenge route. Therefore, these down-regulated genes could also be developed as potential indicators of non-protective vaccines. In this regard, all the selected biomarkers down-regulated in ΔclpB (1300017J02Rik, Slc6a9, Art4, Sptb, and Aqp1) were significantly up-regulated in ΔlpcC. Aqp1, Sptb and Slc6a9 were up-regulated in both ΔgplX and ΔlpcC which means they can be developed to distinguish between strains with at least some protective activity against respiratory challenge.

Table 5.

Selected biomarkers and their relative expressions and fold changes vs spleens from naïve mice.

| Gene Name | Gene Description | Mean | Fold Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | ΔclpB | LVS | ΔgplX | ΔlpcC | ΔclpB/ Naïve |

ΔclpB/ LVS |

ΔclpB/ ΔgplX |

ΔclpB/ ΔlpcC |

||

| Acod1 | aconitate decarboxylase 1 | 29 | 3971 | 1364 | 253 | 31 | 137.8 | 2.9 | 15.7 | 125.7 |

| Saa3 | serum amyloid A 3 | 47 | 5752 | 1000 | 45 | 21 | 122.2 | 5.8 | 128.1 | 282.4 |

| Ccl2 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | 36 | 1606 | 685 | 109 | 65 | 44.7 | 2.3 | 14.9 | 24.8 |

| Clec4e | C-type lectin domain family 4, member e | 83 | 3073 | 978 | 208 | 105 | 37.1 | 3.1 | 14.8 | 29.2 |

| Timp1 | tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 | 90 | 3142 | 1181 | 174 | 95 | 35.0 | 2.7 | 18.1 | 33.2 |

| Serpine1 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 | 46 | 1472 | 447 | 70 | 60 | 31.8 | 3.3 | 21.1 | 24.7 |

| Mmp3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 | 63 | 1862 | 371 | 111 | 59 | 29.8 | 5.0 | 16.8 | 31.7 |

| Inhba | inhibin beta-A | 34 | 858 | 273 | 36 | 24 | 25.2 | 3.1 | 24.0 | 35.1 |

| Cxcl2 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | 13 | 314 | 63 | 12 | 13 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 25.4 | 23.9 |

| Il1rn | interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | 175 | 4269 | 1744 | 389 | 168 | 24.4 | 2.4 | 11.0 | 25.4 |

| Cxcl1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | 29 | 600 | 221 | 45 | 26 | 20.8 | 2.7 | 13.6 | 22.8 |

| Vcan | versican | 45 | 893 | 267 | 95 | 35 | 19.9 | 3.3 | 9.5 | 25.6 |

| Adamts4 | a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 4 | 23 | 415 | 130 | 33 | 25 | 18.2 | 3.2 | 12.6 | 16.9 |

| Cxcl5 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | 54 | 961 | 465 | 96 | 70 | 17.8 | 2.1 | 10.0 | 13.9 |

| Il1r2 | interleukin 1 receptor, type II | 45 | 749 | 227 | 87 | 37 | 16.7 | 3.3 | 8.6 | 20.3 |

| Lipg | lipase, endothelial | 42 | 610 | 248 | 90 | 50 | 14.5 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 12.2 |

| Mmp8 | matrix metallopeptidase 8 | 172 | 2266 | 465 | 314 | 116 | 13.2 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 19.6 |

| Oas1g | 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 1G | 78 | 884 | 423 | 218 | 86 | 11.2 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 10.3 |

| Gzmb | granzyme B | 183 | 1943 | 803 | 497 | 291 | 10.6 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 6.7 |

| Chil1 | chitinase-like 1 | 96 | 1003 | 370 | 196 | 90 | 10.4 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 11.2 |

| Lox | lysyl oxidase | 95 | 905 | 189 | 47 | 62 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 19.2 | 14.6 |

| Il1a | interleukin 1 alpha | 145 | 1291 | 496 | 164 | 151 | 8.9 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 8.5 |

| Ccl3 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | 75 | 478 | 127 | 83 | 93 | 6.3 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 5.2 |

| Ccl4 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | 102 | 585 | 208 | 130 | 174 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 3.4 |

| Hp | haptoglobin | 654 | 3737 | 1587 | 1119 | 580 | 5.7 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 6.4 |

| Il1b | interleukin 1 beta | 1089 | 6125 | 3006 | 1833 | 1115 | 5.6 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 5.5 |

| Il1f9 | interleukin 1 family, member 9 | 108 | 559 | 227 | 211 | 86 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 6.5 |

| Aqp1 | aquaporin 1 | 13520 | 3451 | 9079 | 30537 | 46957 | −3.9 | −2.6 | −8.9 | −13.6 |

| Sptb | spectrin beta, erythrocytic | 8903 | 1854 | 5303 | 21539 | 33398 | −4.8 | −2.9 | −11.6 | −18.0 |

| Art4 | ADP-ribosyltransferase 4 | 406 | 84 | 185 | 610 | 1184 | −4.8 | −2.2 | −7.3 | −14.1 |

| Slc6a9 | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, glycine), member 9 | 648 | 87 | 210 | 1234 | 2130 | −7.5 | −2.4 | −14.2 | −24.6 |

| 1300017J02Rik | RIKEN cDNA 1300017J02 gene | 720 | 59 | 170 | 1114 | 2409 | −12.2 | −2.9 | −18.9 | −40.8 |

3.2. Proteomic Confirmation of Transcriptomics Findings

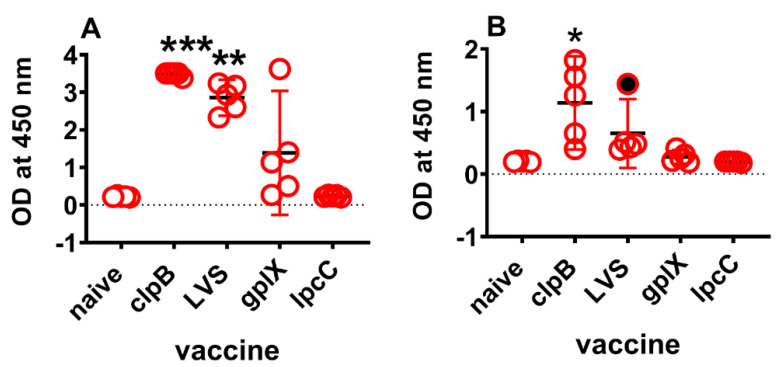

Previously, we have reported [27] that IFNγ, IL-6, CcL2 (MCP-1), and Cxcl1 (KC) proteins are over produced in the spleens and sera of mice immunized ID four days earlier with ΔclpB, versus gplX or lpcC. LVS elicited similar responses to ΔclpB (unpublished). In this study, we found that IFNγ, IL-6, and CcL2 are among the up-regulated genes by both ΔclpB and LVS. In addition, Saa3 is highly up-regulated by vaccination with both ΔclpB (122-fold) and LVS (21-fold). To determine whether these finding hold at the translational level, we first used a commercial ELISA kit to examine serum levels of Saa3 in the same mice that provided the spleens for transcriptional analyses. In sera diluted 2000-fold, Saa3 levels in mice immunized with ΔclpB (adjusted p = 0.0008) or LVS (adjusted p = 0.03), were significantly higher than background (Figure 3). However, at 1:10,000 dilution serum Saa3 levels were only significantly higher than background (adjusted p = 0.01) in mice immunized with ΔclpB (Figure 3). Therefore, depending on dilution, serum Saa3 levels 4 days after vaccination can discriminate between vaccines that provide some degree of protection against respiratory challenge versus those that do not or ΔclpB versus all three other vaccine candidates.

Figure 3.

Serum Saa3 levels 4 days after vaccination. Blood was collected from mice (n = 5/ group) 4 days after ID vaccination with one or other vaccine strain. Sera were diluted 2000-fold (A) or 10,000-fold (B) and tested for the presence of Saa3 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Colour reaction was stopped after 15 minutes. Graphs were plotted as means (horizontal black dash) with 95% CI (red vertical lines). Dotted line is the limit of detection. Asterisks denote significantly higher levels than naïve sera by Kruskal Wallis analysis followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. *** (adjusted p = 0.0008), ** (adjusted p = 0.03), * (adjusted p = 0.01). Filled circle, outlier identified by ROUT analysis and excluded from calculations.

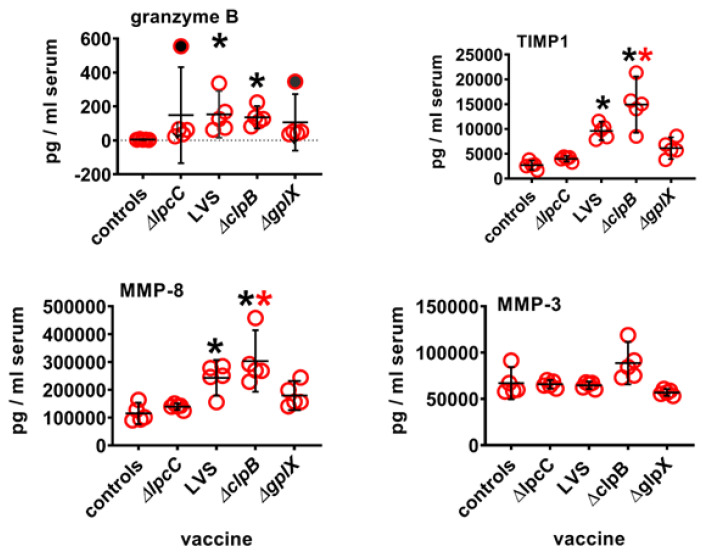

Next, we looked at serum granzyme B, TIMP1, MMP3 and MMP8 levels on day four after vaccination by multiplex (Luminex) assay (Figure 4). The results show that compared to naïve mouse serum, levels of granzyme B, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP1), and matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP8), but not MMP3, were significantly up-regulated in the sera of mice immunized with either ΔclpB or LVS even after correction for multiple comparisons. Serum levels of TIMP-1 and MMP-8 were also significantly higher in mice immunized with ΔclpB vs. ΔlpcC. However, in no cases were levels of these proteins significantly greater in mice immunized with ΔclpB versus LVS or ΔgplX. It remains to be determined how much this holds true for the other highly up-regulated and down-regulated genes in Table 5 for which proteomic assays were unavailable.

Figure 4.

Serum protein levels four days after immunization. Mice (n = 4–5/group) were immunized ID with 105 CFU of one or other vaccine strain. Four days later serum was prepared from each mouse and assayed for the presence of Granzyme B, TIMP1, MMP3, and MMP8. Data were analysed using Kruskal Wallis test to compare each group to every other group followed by Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons. Filled circles (outliers by ROUT analysis) removed prior to calculations. Black asterisks, significantly greater than levels found in control serum, red asterisks significantly greater than ΔlpcC (adjusted p ≤ 0.04); 95% CI (vertical black lines) and means (horizontal black lines).

4. Discussion

The FDA Animal Rule for the approval of vaccines against Ftt requires evidence that CoP from two animal models likely predict their efficacy in humans. Currently, only LVS has been shown to protect humans against inhalation of virulent Ftt. This data stems solely from experiments conducted between 1960–1975 in which volunteers or tularemia researchers immunized by various routes with LVS were subsequently exposed to SCHU S4 [16,17,18,21,52,53]. These studies showed that LVS administered by scarification provided the simplest and safest means of eliciting protection, though it proved sub-optimal against aerosol challenge. Had LVS proved to be 100% effective against the latter, then any signs of vaccine take (e.g., eschar formation at the immunization site, or seroconversion to LVS) could have served as a straightforward CoP. Despite vaccine take being 100% in these experiments, in one pivotal study, 80% of unvaccinated individuals became ill within a few days following inhalation of between 10–50 CFU of SCHU S4, as did 3/18 individuals immunized with LVS [17]. Similarly, LVS elicited protection against aerosol challenge with a breakthrough threshold of ~1000 human infectious doses waned from 100% at 2 months to 25% at 11 months after vaccination [2]. When these human experiments were performed, only relatively crude measures of immunity were available. Namely, seroconversion (bacterial agglutination titer) that proved unreliable as a CoP [54]. Thus, neither vaccine take nor antibody titer predicted longer term protection. Because CMI and its critical role in protection against facultative intracellular bacterial pathogens was in its infancy at this time, no attempts were made to measure such immune responses elicted by LVS as potential CoP.

Nowadays, there is abundant animal data showing aspects of CMI that are crucial to protective immunity following vaccination with LVS (reviewed in [31,55]). However, in the absence of any accompanying human challenge data, it is difficult to predict which of these responses might correlate with long-lasting protection given its short-term zenith to rapid nadir in early challenge studies. For novel experimental vaccines, that have only been shown to be effective in animal models, the bridge to predicting their efficacy in humans remains even more challenging. Nevertheless, animal models can at least provide a starting point. In this regard, we have developed a deletion mutant of SCHU S4, ΔclpB, that offers better protection than LVS to BALB/c mice challenged IN or by aerosol with virulent Ftt [26,27]. Additionally, ΔclpB, LVS and ΔgplX all protect mice against ID challenge with virulent Ftt, whereas mutant strain ΔlpcC signally fails in both regards. Our prior attempts to correlate selected molecular immune responses to vaccination with these mutants were unsuccessful and biased by available reagents [24,25,26,27,56]. To determine whether other early host molecular responses to vaccination could predict the relative efficacy of these experimental vaccine strains, we performed more impartial transcriptomic profiling on the spleens of mice vaccinated ID 4 days earlier with 105 CFU of one or other vaccine strain. The spleen was used as a surrogate for PBMC that are in too short supply in individual mice to allow this type of approach. Our analyses revealed several up- and down- regulated genes associated with canonical CMI pathways that correlated with the superior protective capability of ΔclpB. Additionally, these studies identified a large number of other potential CoP. Among the most up-regulated transcripts in the spleens of BALB/c mice immunized with ΔclpB versus the other three test strains (Table 5 and Table S1) were, IFNγ, IL-6, Ccl2 (MCP1) and CxCL1 (KC). Interestingly, we previously showed this to be the case when spleen homogenates and serum from mice immunized four days earlier were examined for the proteins encoded by these genes. Moreover, these proteins were all produced in significantly higher quantities in mice immunized with ΔclpB versus ΔgplX or ΔlpcC [27]. However, there were no significant differences in the levels of these proteins produced in the spleens or sera of mice immunized four days earlier with ΔclpB vs. LVS. Our statistical analysis of transcript counts confirmed that IFNγ and IL-6 were not significantly up-regulated in mice immunized with ΔclpB vs. LVS. Moreover, these proteins were similarly up-regulated in mice that were protected (BALB/c) or not (C57BL/6) by immunization with ΔclpB [26]. Overall, our prior findings indicated that our previous selection of serum or splenic cytokines or chemokines were poor CoP. However, these were restricted by commercial availability of antibodies to target immune molecules. In contrast, transcriptomics allows a much broader and less biased view of host responses to vaccination that can reveal non-canonical responses not normally associated with protective CMI (reviewed in [57]). In this regard, the current study revealed several genes, not routinely associated with protective CMI, that were many-fold up-regulated in mice immunized with ΔclpB vs. LVS, ΔgplX or ΔlpcC (Table 5 and Table S5). For instance, transcripts for serum amyloid A3 (Saa3) were significantly up-regulated relative to naïve mice by 122-fold versus 21-fold by ΔclpB vs. LVS, respectively, but not at all by ΔgplX and ΔlpcC. Therefore, an ELISA specific for mouse Saa3 was used to examine its levels in the sera from the same mice used for splenic transcriptional analysis. The results (Figure 3) clearly recapitulated the transcriptomics data (ΔclpB > LVS > ΔgplX > ΔlpcC), making Saa3 a promising surrogate CoP. This was the case too for serum granzyme B, TIMP1, and MMP8 measured by Luminex whereas MPP3 showed no up-regulation in protein expression (Figure 4). Several other transcripts were also up-regulated by at least 2-fold in ΔclpB- vs. LVS-immunized mice and substantially more so compared to mice immunized with ΔgplX or ΔlpcC. In all our prior comparative efficacy studies of different vaccine strains, LVS was always the next best performing vaccine after ΔclpB at providing protection against respiratory challenge with SCHU S4. Therefore, it is unsurprising that they induce the most similar transcriptional profiles in mice. It is interesting to note too, that down-regulation of certain genes (e.g., Aqp1, Sptb) also correlate with the ability to elicit protection against respiratory challenge (Table S4). Whether or not any or a small combination of these differences are sufficient to serve as CoP for ranking the relative efficacy of tularemia vaccines in other mammals including humans remains to be determined.

Although our studies were limited to BALB/c mice, several groups have performed comprehensive transcriptional and translational analysis using PBMC recovered from individual humans for up to 2 weeks following immunization with LVS [42,43,57]. Fuller et al. examined the transcriptomes of PBMC taken from volunteers at -6, and 1, 2, 8, 14 days after immunization with LVS from a batch lot produced for the United States Army Medical Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) in the early 1960s [42,43]. Despite the age of this vaccine, others have demonstrated that stored at −80 °C, it elicited similar CMI responses in humans over a test period of >35 years [58]. The former studies showed transcriptional changes primarily in molecular pathways associated with innate immunity. Much more recently, others [57] have comprehensively mapped transcriptional changes in PBMC from human volunteers immunized 1, 2, 7 or 14 days earlier with USAMRIID LVS or a newer batch manufactured in 2007 by the Dynport Vaccine Company under more appropriate GMP conditions [59]. Again, the individual responses were very reproducible. However, in both cases, the fold change in transcript abundance was ≤3-fold in either direction compared with the exponentially higher changes observed in mice spleens in the current study. The latter study showed also that both LVS vaccine lots induced small (<2-fold), but significant changes in a few serum cytokines and chemokines in contrast to the >1000-fold increases we previously found in mice [27]. Finally, a proteomics study on PBMC from LVS vaccines on days 7 and 14 showed ≤2-fold changes in abundance of numerous proteins following vaccination [45]. Because of the massive sizes of the datasets produced from human transcriptomics and proteomics studies, it is impossible to do them full credit herein. Instead, we have produced a Supplementary table (Table S5) showing the largest changes over time in transcriptomes and proteomes in human PMBC following immunization with LVS. Surprisingly, there was little overlap between the transcription results of Fuller et al. and those of Natrajan et al., Table S5). This was also the case with the proteomics study by Chang et al. [45]. Finally, none of these datasets showed much overlap with the mouse data generated in the current study. The reasons for all of the aforementioned differences are likely multifold and include: (1), Different host species naturally react differently at the genetic level to vaccination with live tularemia vaccines; (2), the live vaccine candidates examined in the current study cause systemic infection in mice to varying degrees, thus exponentially amplifying the original antigenic burden; (3), serum cytokine responses in mice are diluted in 5.0 mL of blood versus 5.0 L of blood in humans (a differential that is eliminated using the macrophage killing assay (MKA, described below); (4), ultimately it is the acquired immune responses to vaccination that determine the degree of protective immunity and early transcriptional responses in different host species lead to similar acquired immunological outcomes as suggested by the MKA and other assays; (5), PBMC do not fully reflect immunogenetic changes occurring in the lymph nodes, the primary sites of antigen processing and presentation; (6), the gap between day 2 and 7 data collection points for humans miss information generated in mice on day 4 after vaccination; (7), transcriptional changes that occur before the onset of acquired CMI correlate more with mechanisms of protection rather than CoP. In mice and humans, the first measurable evidence of acquired CMI following vaccination with LVS occurs starting at approximately 2 weeks [60,61].

Besides using early post-vaccination transcriptional analyses that occur at the cusp of the acquired immune response, others have developed functional assays, preferred by regulatory agencies, to examine potential CoP following vaccination with live tularemia vaccines including LVS. The most promising of these is the so called “macrophage killing assay” (MKA) developed by Karen Elkins and colleagues at the US FDA in an attempt to reveal CoP for novel tuberculosis and tularemia vaccines [62,63]. Briefly, the assay involves infecting quiescent, adherent host macrophages contained within wells of tissue culture plates with Ft. In this condition, Ft will grow exponentially within the macrophages and kill them within 72 h. However, if immune T cells from the same, previously vaccinated, host are overlaid on top of the infected macrophages, then Ft multiplication is rapidly curtailed and can be measured as a logarithmic decrease in CFU. Additionally, the transcriptomes, and phenotypes of the T cells and macrophages that remain at the end of the assay can be determined as can the contents of the well supernatants [35,36,37,64]. In this regard, we previously showed that the enhanced efficacy of ΔclpB vs. LVS in a murine aerosol challenge model was associated with a concomitant increase in the levels of pulmonary IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-17 seven days after challenge [24,26,29]. Using the MKA and these cytokines individually or in mixtures, we have shown that combining all three molecules results in the most effective killing of SCHU S4 (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, overall this assay appears to be capable of fully recapitulating the in vivo protective immune response. Moreover, the MKA can be used with multiple species, to allow for the discovery of pan-species specific CoP. In this regard, the MKA has already been successfully employed in mice, rats, and humans immunized with LVS or ΔclpB [37,40,41,62,65].

5. Concluding Remarks

This study shows that a potentially simple serum-based test for one or a few molecules could be used to develop a CoP profile for humans vaccinated with ΔclpB. In particular, this study shows that vaccination with ΔclpB especially induces significant up- or down- regulation of genes hitherto not associated with protective immunity to respiratory challenge with virulent F. tularensis. A finding in keeping with several bioinformatics studies that have shown unexpected CoP for LVS and several vaccines against other infectious diseases [57]. We have recently made a batch lot of ΔclpB under GMP conditions [66] that will be used to conduct clinical trials sometime in 2022 or 2023. Thereafter, we will be able to directly compare human immune responses to vaccination with ΔclpB and LVS that could reveal either a common or unique CoP for these two vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dao Ly and Alain Tchagang for their assistant in the early stage of data analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms10010036/s1, Figure S1. Effects of IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-17a alone or in combination on macrophage-mediated killing of Ftt, Table S1. Complete set of differentially expressed genes, Table S2. Enriched KEGG pathways in commonly up- or down-regulated gene groups by all four vaccinations, Table S3. Significantly down-regulated pathways unique to ΔclpB, but uniquely up-regulated in ΔlpcC, Table S4. Detailed information on the 32 selected biomarkers shown in Table 5, Table S5. Comparison of published studies of gene/protein expression changes in human PBMC following vaccination by scarification with LVS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y.L., Y.P. and J.W.C.; methodology, Q.Y.L., Y.P., J.W.C. and F.S.; software, Z.L. and Y.P.; formal analysis, Q.Y.L., Y.P. and F.S.; investigation, S.L., Z.L. and F.S.; resources, Q.Y.L., J.W.C., Y.P. and F.S.; data curation, S.L., Z.L. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.C. and Q.Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.W.C., Q.Y.L. and Y.P.; visualization, S.L., Z.L. and F.S.; supervision, Q.Y.L. and J.W.C.; project administration, Q.Y.L., Y.P. and J.W.C.; funding acquisition, J.W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded in part by internal funding from the National Research Council of Canada and Prime Contract HDTRA114-AMD2-CBM-01-2-0042 from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work was performed under National Research Council Canada animal use protocol # 2015.01 in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines for the use and care of laboratory animals (https://ccac.ca/en/standards/guidelines/; accessed on 6 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data are available in the GEO repository with access number GSE186408. The remainder of the data presented in this study are all available in the present article.

Conflicts of Interest

Q.Y.L., S.L., Y.P., Z.L., F.S. and J.W.C. report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sjostedt A. Tularemia: History, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1105:1–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCruumb F.R. Aerosol Infection of Man with Pasteurella Tularensis. Bacteriol. Rev. 1961;25:262–267. doi: 10.1128/br.25.3.262-267.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyston P.C. Francisella tularensis: Unravelling the secrets of an intracellular pathogen. Pt 8J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:921–930. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/000653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma J., Mares C.A., Li Q., Morris E.G., Teale J.M. Features of sepsis caused by pulmonary infection with Francisella tularensis Type A strain. Microb. Pathog. 2011;51:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosio C.M. The subversion of the immune system by francisella tularensis. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timofeev V., Titareva G., Bahtejeva I., Kombarova T., Kravchenko T., Mokrievich A., Dyatlov I. The Comparative Virulence of Francisella tularensis Subsp. mediasiatica for Vaccinated Laboratory Animals. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1403. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlan J.W., Chen W., Shen H., Webb A., KuoLee R. Experimental tularemia in mice challenged by aerosol or intradermally with virulent strains of Francisella tularensis: Bacteriologic and histopathologic studies. Microb. Pathog. 2003;34:239–248. doi: 10.1016/S0882-4010(03)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarnvik A., Eriksson M., Sandstrom G., Sjostedt A. Francisella tularensis—A model for studies of the immune response to intracellular bacteria in man. Immunology. 1992;76:349–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schricker R.L., Eigelsbach H.T., Mitten J.Q., Hall W.C. Pathogenesis of tularemia in monkeys aerogenically exposed to Francisella tularensis 425. Infect. Immun. 1972;5:734–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.734-744.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer C.G., May J. Germs employed as biological weapons. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notf. Schmerzther. AINS. 2002;37:538–546. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kortepeter M.G., Parker G.W. Potential biological weapons threats. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999;5:523–527. doi: 10.3201/eid0504.990411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyston P.C., Sjostedt A., Titball R.W. Tularaemia: Bioterrorism defence renews interest in Francisella tularensis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:967–978. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis D.T., Inglesby T.V., Henderson D.A., Bartlett J.G., Ascher M.S., Eitzen E., Fine A.D., Friedlander A.M., Hauer J., Layton M., et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon: Medical and public health management. JAMA. 2001;285:2763–2773. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]