Abstract

This study examines breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalizations, and mortality in March-August 2021, when the Delta variant predominated, among a general US cohort vaccinated with mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2.

Immune responses to mRNA-1273 (Moderna) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccines decline by 6 months after vaccination,1 although antibody titers are higher with mRNA-1273.1,2 Comparison of vaccinated nonimmunocompromised adults showed lower risk of hospitalization for recipients of mRNA-1273 than BNT162b2 during March-August 2021.3 This study examined breakthrough infections, hospitalizations, and mortality in a general population for these 2 vaccines during the Delta period while considering risk characteristics of vaccine recipients and the varying time since vaccination.

Methods

We used the cloud-based TriNetX Analytics Platform to obtain web-based real-time secure access to fully deidentified electronic health records of 89 million patients from 63 health care organizations including inpatient and outpatient settings, representing 27% of the US population from 50 states covering diverse geographic, age, race and ethnicity, income, and insurance groups. TriNetX Analytics built-in functions allow for patient-level analyses. Because this study used only deidentified patient records, it was exempted from review by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board.

We included breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections (defined by a positive laboratory test result for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA) that occurred between July and November 2021, when the Delta variant predominated4 in fully vaccinated individuals receiving 2 doses of an mRNA vaccine (anytime between December 2020 and November 2021) who had no booster shot and no prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Breakthrough infections were included if occurring 14 days after full vaccination. Monthly incidence rates of breakthrough infections (cases per 1000 person-days) were compared in those receiving mRNA-1273 vs BNT162b2. The 2 cohorts were propensity score matched for demographics, social determinants of health, transplants, and comorbidities previously associated with COVID-19 risk or severe outcomes5 (Table). Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed by following patients for 14 days after the index event (full vaccination), which accounted for time since vaccination. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated based on comparison of time-to-event rates in the 2 matched cohorts. Hospitalizations and mortality in infected patients for 60 days starting from the day of infection were compared between the propensity score–matched cohorts and COVID-19–related therapeutics.6 All statistical analyses were conducted within the TriNetX Analytics Platform with significance set at a 2-sided P < .05.

Table. Characteristics of the mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 Cohorts Before and After Propensity Score Matchinga.

| Characteristics | Vaccinated | Infected | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | After matching | Before matching | After matching | |||||||||

| mRNA-1273 | BNT162b2 | P valueb | mRNA-1273 | BNT162b2 | P valueb | mRNA-1273 | BNT162b2 | P valueb | mRNA-1273 | BNT162b2 | P valueb | |

| Total No. | 62 628 | 574 538 | 62 584 | 62 584 | 3078 | 18 737 | 3054 | 3054 | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.2 (18.5) | 51 (20.5) | <.001 | 62.2 (18.5) | 62.1 (18.7) | .40 | 63.8 (18.6) | 55.5 (21.5) | <.001 | 63.7 (18.6) | 63.3 (18.6) | .35 |

| Sex, % | ||||||||||||

| Female | 58.3 | 55.9 | <.001 | 58.3 | 58.9 | .04 | 61.0 | 59.2 | .06 | 60.8 | 61.8 | .43 |

| Male | 41.7 | 44.0 | <.001 | 41.7 | 41.0 | .02 | 39.0 | 40.8 | .06 | 39.2 | 38.2 | .44 |

| Ethnicity, %c | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3.9 | 12.1 | <.001 | 3.9 | 3.6 | .01 | 4.1 | 10.6 | <.001 | 4.1 | 3.5 | .26 |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 66.3 | 74.1 | <.001 | 66.4 | 67.0 | .02 | 71.1 | 77.0 | <.001 | 71.1 | 70.8 | .82 |

| Unknown | 29.7 | 13.8 | <.001 | 29.7 | 29.4 | .18 | 24.8 | 12.1 | <.001 | 24.7 | 25.6 | .43 |

| Race, %c | ||||||||||||

| African American/Black | 18.4 | 14.4 | <.001 | 18.4 | 17.9 | .02 | 14.5 | 17.4 | <.001 | 14.6 | 13.7 | .29 |

| Asian | 5.2 | 7.9 | <.001 | 5.2 | 4.9 | .003 | 5.3 | 5.4 | .85 | 5.3 | 5.1 | .82 |

| White | 64.7 | 63.4 | <.001 | 64.7 | 65.6 | .002 | 72.5 | 67.2 | <.001 | 72.4 | 73.9 | .18 |

| Unknown | 11.3 | 13.4 | <.001 | 11.3 | 11.3 | .98 | 7.1 | 9.0 | <.001 | 7.1 | 7.2 | .92 |

| Adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, %d | 3.0 | 1.4 | <.001 | 3.0 | 2.7 | .003 | 5.8 | 3.6 | <.001 | 5.7 | 5.8 | .83 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 39.6 | 20.8 | <.001 | 39.5 | 39.9 | .19 | 51.9 | 39.7 | <.001 | 51.6 | 50.0 | .20 |

| Heart diseases | 11.2 | 4.7 | <.001 | 11.1 | 11.4 | .14 | 18.8 | 11.8 | <.001 | 18.5 | 17.9 | .53 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 7.2 | 3.2 | <.001 | 7.1 | 7.2 | .76 | 12.9 | 8.2 | <.001 | 12.7 | 13.4 | .45 |

| Obesity | 16.4 | 10.0 | <.001 | 16.4 | 15.8 | .009 | 23.1 | 19.6 | <.001 | 23.0 | 21.8 | .24 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 15.5 | 7.7 | <.001 | 15.5 | 15.3 | .36 | 19.6 | 15.6 | <.001 | 19.6 | 19.0 | .54 |

| Cancers | 31.3 | 14.6 | <.001 | 31.2 | 32.2 | <.001 | 45.4 | 26.2 | <.001 | 45.1 | 45.1 | .98 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 14.8 | 8.4 | <.001 | 14.8 | 14.4 | .06 | 24.6 | 18.6 | <.001 | 24.4 | 23.1 | .22 |

| Liver diseases | 6.8 | 3.2 | <.001 | 6.8 | 6.4 | .003 | 10.8 | 7.2 | <.001 | 10.7 | 10.2 | .50 |

| Blood disorders involving immune mechanisms | 19.8 | 10.1 | <.001 | 19.8 | 19.9 | .56 | 33.7 | 22.4 | <.001 | 33.4 | 32.3 | .38 |

| HIV infection | 0.6 | 0.4 | <.001 | 0.6 | 0.6 | .63 | 0.6 | 0.7 | .33 | 0.6 | 0.6 | >.99 |

| Dementia | 1.1 | 0.4 | <.001 | 1.1 | 1.1 | .91 | 2.0 | 1.2 | <.001 | 2.0 | 2.1 | .78 |

| Substance use disorders | 9.3 | 4.7 | <.001 | 9.3 | 8.9 | .02 | 12.3 | 9.0 | <.001 | 12.3 | 11.8 | .58 |

| Depression | 10.4 | 6.4 | <.001 | 10.4 | 9.9 | .006 | 18.6 | 12.9 | <.001 | 18.4 | 17.3 | .26 |

| Anxiety | 16.1 | 10.6 | <.001 | 16.1 | 15.9 | .37 | 27.7 | 20.8 | <.001 | 27.4 | 26.4 | .37 |

| Organ transplant | 1.2 | 0.5 | <.001 | 1.2 | 1.2 | .58 | 2.8 | 1.4 | <.001 | 2.7 | 2.6 | .87 |

The vaccinated mRNA-1273 cohort comprised fully vaccinated individuals receiving 2 doses of mRNA-1273 vaccine anytime between December 2020 and November 2021 but who had no booster shot and no prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. The vaccinated BNT162b2 cohort was similar to the vaccinated mRNA-1273 cohort but comprised individuals receiving BNT162b2 vaccine. The infected mRNA-1273 cohort comprised fully vaccinated mRNA-1273 recipients who were first infected between July and November 2021. The infected BNT162b2 cohort comprised fully vaccinated BNT162b2 recipients who were first infected between July and November 2021. Cohorts were propensity matched based on covariates shown in the table.

Test for significant difference between the 2 cohorts based on 2-tailed, 2-proportion z test conducted within the TriNetX Analytics Network.

Race and ethnicity were defined based on the TriNetX Analytics electronic health record database and were included in the study because they are known to be associated with both risk and associated outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infections.

The status of adverse socioeconomic determinants of health was based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes (Z55-Z65), including “problems related to education and literacy,” “problems related to employment and unemployment,” “occupational exposure to risk factors,” “problems related to housing and economic circumstances,” and “problems related to upbringing.”

Results

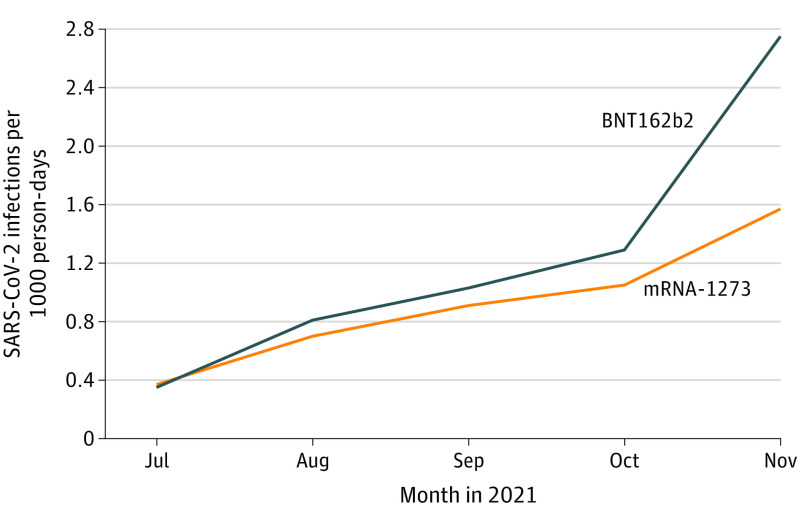

The mRNA-1273 cohort (n = 62 628) was significantly older and had more comorbidities than the BNT162b2 cohort (n = 574 538), and the differences decreased after matching (Table). The monthly incidence rate of breakthrough infections increased from July to November 2021 in both cohorts, was higher in the BNT162b2 cohort than the mRNA-1273 cohort, and reached 2.8 and 1.6 cases per 1000 person-days in November, respectively (P < .001) (Figure). After matching, the mRNA-1273 cohort (n = 62 584) had a significantly lower hazard for breakthrough infections compared with the matched BNT162b2 cohort (n = 62 584) (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.80-0.89).

Figure. Monthly Incidence Rates of Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 Infections From July to November 2021 in 2 Cohorts.

The mRNA-1273 cohort comprised fully vaccinated individuals receiving 2 doses of mRNA-1273 vaccine anytime between December 2020 and November 2021 but who had no booster shot and no prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. The BNT162b2 cohort was similar to the mRNA-1273 cohort but comprised individuals receiving BNT162b2 vaccine.

Among infected patients, mRNA-1273 recipients were older than BNT162b2 recipients, differed in sex and racial and ethnic composition, and had significantly more comorbidities and adverse social determinants of health, but differences were no longer significant after matching (Table). The 60-day hospitalization risk was 12.7% (392/3078) for mRNA-1273 recipients and 13.3% (2489/18 737) for BNT162b2 recipients. The 60-day mortality was 1.14% (35/3078) and 1.10% (207/18 737) for mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 recipients, respectively. Among the matched cohorts, mRNA-1273 recipients (n = 3054) had a lower risk of 60-day hospitalizations than BNT162b2 recipients (n = 3054) (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.91). No significant difference was observed for mortality (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.50-1.23).

Discussion

This study found that recipients of mRNA-1273 compared with BNT162b2 had a lower risk of breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections and hospitalizations during the Delta period. Study limitations include that (1) the observational, retrospective nature of the study based on patient records could introduce selection, information, and follow-up biases; (2) generalizability of the results from the TriNetX platform is unknown; (3) differences between cohorts in geographic distribution and virus circulation could confound the results; and (4) the cohorts were similar after matching but small, statistically significant differences in some characteristics remained. However, those differences would lead to an underestimation of the differences between vaccines.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.Collier AY, Yu J, McMahan K, et al. Differential kinetics of immune responses elicited by Covid-19 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(21):2010-2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2115596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steensels D, Pierlet N, Penders J, Mesotten D, Heylen L. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antibody response following vaccination with BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1533-1535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Self WH, Tenforde MW, Rhoads JP, et al. ; IVY Network . Comparative effectiveness of Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions—United States, March-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(38):1337-1343. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7038e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID Data Tracker variant proportions. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 and people with certain medical conditions. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Information for clinicians on investigational therapeutics for patients with COVID-19. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/therapeutic-options.html