Abstract

The underexplored biodiversity of seaweeds has recently drawn great attention from researchers to find the bioactive compounds that might contribute to the growth of the blue economy. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of seasonal growth (from May to September) on the in vitro antioxidant (FRAP, DPPH, and ORAC) and antimicrobial effects (MIC and MBC) of Cystoseira compressa collected in the Central Adriatic Sea. Algal compounds were analyzed by UPLC-PDA-ESI-QTOF, and TPC and TTC were determined. Fatty acids, among which oleic acid, palmitoleic acid, and palmitic acid were the dominant compounds in samples. The highest TPC, TTC and FRAP were obtained for June extract, 83.4 ± 4.0 mg GAE/g, 8.8 ± 0.8 mg CE/g and 2.7 ± 0.1 mM TE, respectively. The highest ORAC value of 72.1 ± 1.2 µM TE was obtained for the August samples, and all samples showed extremely high free radical scavenging activity and DPPH inhibition (>80%). The MIC and MBC results showed the best antibacterial activity for the June, July and August samples, when sea temperature was the highest, against Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella enteritidis. The results show C. compressa as a potential species for the industrial production of nutraceuticals or functional food ingredients.

Keywords: Cystoseira compressa, microwave-assisted extraction, green extraction, biological activity, seaweed, seasonal variations, nutraceuticals, fatty acids

1. Introduction

Among seaweeds, the brown macroalgae (Phaeophyceae) have been identified as an outstanding source of phenolic compounds, from simple phenolic acids to more complex polymers such as tannins (mainly phlorotannins). Algal phlorotannins, a group of phenolic compounds restricted to the polymers of phloroglucinol, present a heterogeneous and high molecular weight group of compounds (from 126 Da to 650 kDa) which are verified in terrestrial plants [1,2]. The phlorotannins play an important role in the cellular and ecological growth and tissue healing of alga but also show strong antioxidant, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and antitumor properties [3,4,5,6].

Brown fucoid algae of the genus Cystoseira sensu lato (Sargassaceae) consist of 40 species of large marine canopy-forming macroalgae found along the Atlantic–Mediterranean coasts [7,8]. So far, a total of 214 compounds have been isolated from sixteen Cystoseira species, and the chemical constituents of Cystoseira spp. were found to contain fatty acids and derivatives, terpenoids, steroids, carbohydrates, phlorotannins, phenolic compounds, pigments and vitamins [7]. The chemical composition of the alga depends on numerous ecological factors such as temperature, salinity, UV irradiation, collecting season, depth, geographic location, thallus development, etc. However, their individual and synergistic effect on the brown alga chemical profile and biological activity is still relatively unknown. Recent studies showed that seasonality and thallus vegetative parts significantly affect the nutritional and chemical profile of alga [9]. It is considered that higher nutritional and phenolic content, higher polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) content, higher vitamin and mineral content, as well as the antiproliferative properties of brown algae from brown fucoid algae were obtained during hot and dry summer seasons and higher sea temperatures [10,11,12,13]. On the other hand, no seasonal effect was recorded for the pigment profile and fucoxanthin content, nor total phenolic content and antimicrobial activity of the genera Padina, Colpomenia, Saccharina or Dictyota [14,15]. So far, there are no reports on seasonal variations in chemical profile nor the biological activity of Cystoseira spp.

Cystoseira spp. composition suggests their high nutritional value with potential applications in the nutraceutical industry. A range of 29–46% of PUFA, a low n-6 PUFA/n-3 PUFA ratio as well as favorable unsaturation, atherogenicity, and thrombogenicity indices were observed in several Cystoseira species [16]. Compounds from Cystoseira species are important sources of nutraceuticals and may be considered as functional foods, such as extracts of C. tamariscifolia and C. nodicaulis that were able to protect a human dopaminergic cell line from hydrogen peroxide-induced cytotoxicity and inhibit cholinesterases, while those from C. crinita showed significant cytotoxic activity against human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7 cells), inducing apoptosis and autophagy [17,18]. Besides non-volatiles, the essential oil constituents of C. compressa and their seasonal changes have been identified and among them for a large number of compounds a broad range of biological activities have been already proved [19]. So far, over 50 biological properties have been attributed to compounds found in genus Cystoseira, and the most reported are antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, anticancer, cholinesterase inhibition, antidiabetic, and antiherpetic activities [7,20,21,22,23,24]. Phlorotannins are regarded as responsible for high antioxidant activity (e.g., free radical scavenging ability) [1,25,26,27]. Besides, there is little information on the antimicrobial activity of Cystoseira spp. extracts against major foodborne Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [28].

The aim of this study was to investigate the chemical composition of C. compressa, one of the most widely distributed algae in the Adriatic Sea, to determine changes in its antioxidant and antimicrobial activity over the seasonal growth (May–September) when the algae are in the growing and reproductive phases, and the development of dense thallus occurs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Total Phenolic Content, Total Tannin Content and Antioxidant Activity

Seaweed extracts were screened for total phenolic content (TPC), total tannin content (TTC) and antioxidant activity measured by ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging ability (DPPH) and the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC).

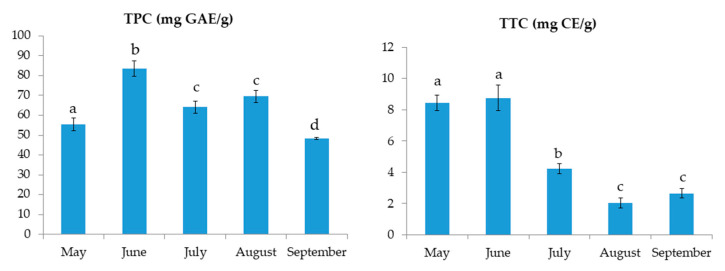

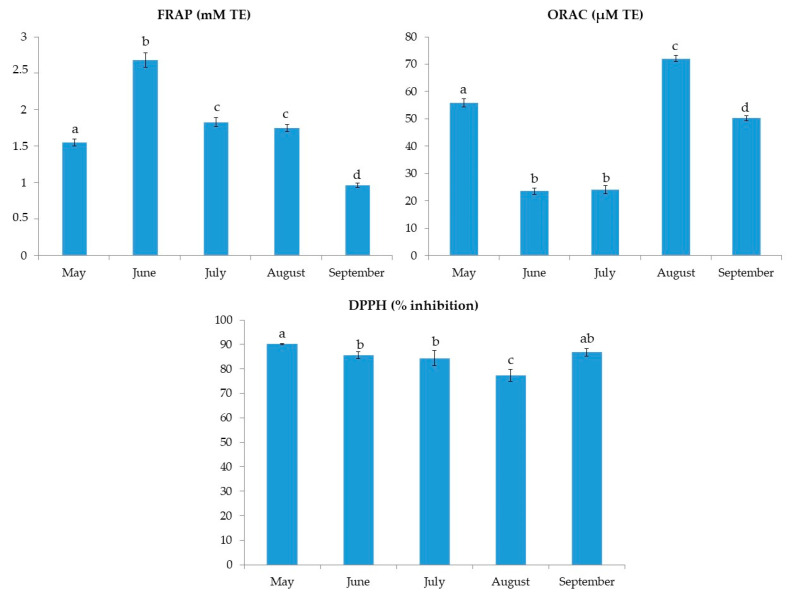

The results of TPC and TTC for C. compressa are shown in Figure 1. The results for TPC varied from 48.2 ± 0.5 to 83.4 ± 4.0 mg GAE/g. The highest TPC was found in June samples. On the other hand, the TTC values ranged from 2.0 ± 0.3 to 8.8 ± 0.8 mg CE/g with the highest value found also in June, followed by the extract from May. The FRAP values, shown in Figure 2, ranged from 1.0 ± 0.0 to 2.7 ± 0.1 mM TE. Similar to TPC and TTC, the highest FRAP result was obtained for June, showing the reducing activity of >2.5 mM TE. TPC and FRAP results were in high correlation (0.956; p < 0.01). The ORAC results are shown in Figure 2. The seaweed extracts were 200-fold diluted for ORAC assay. Among the investigated samples, the highest ORAC value of 72.1 ± 1.2 µM TE was found in the August extract, with extracts from May having the second best. June and July extracts had the lowest ORAC values, more than 3-fold lower in comparison to the August extract. The DPPH radical inhibitions (in percentages) are shown in Figure 2. The extract from May had the highest inhibition (90.2%) while the August extract had the lowest inhibition (77.3%). The activity of other extracts was similar, around 85%. In the growing season, the sea temperature was the lowest in May (18.3 °C) and it rose every month till August when it peaked at 26.9 °C. Finally, a decrease in the temperature by 2.2 °C was observed in September (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Total phenolic content (TPC) and total tannin content (TTC) of C. compressa extracts from May to September. a–d different letters denote statistically significant difference (n = 4).

Figure 2.

FRAP, ORAC and DPPH inhibition results for C. compressa extracts from May to September. a–d different letters denote statistically significant difference (n = 4).

Table 1.

Sea temperature and salinity recorded during the harvest of the algal samples.

| May | June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 18.3 | 21.8 | 22.4 | 26.9 | 24.7 |

| Salinity (PSU) | 37.4 | 38.1 | 38.3 | 38.3 | 38.3 |

The TPC of alga varies with seasonal changes of sea temperature, salinity, light intensity, geographical location and depth, as well as other biological factors such as age, size, the life cycle of the seaweed, presence of herbivores [1]. In this study, the geographical location and depth were eliminated as a factor as samples were collected from the same area and depth each month. The TPC, TTC and antioxidant activity results showed no correlation to the sea temperature and salinity. If the growth of alga is considered, in June when the TPC, TTC and FRAP were the highest, C. compressa had a fully developed, densely ramified thalli with aerocysts. In May the thalli are not yet fully developed, while in July–September it is less dense, aerocysts appear in fewer numbers [29].

The TPC of Cystoseira species was previously investigated and researchers reported a strong effect of harvesting location and seasonal changes, especially temperature. Mancuso et al. [12] investigated TPC in C. compressa from eight locations along the Italian coast and confirmed the change of TPC with geographical location. The TPC ranged between different locations from 0.1 to 0.5% of algal dry weight (DW). The authors observed the increase in TPC with the rise of sea temperature (measured at different locations). Accordingly, the highest TPC of 0.53% DW was recorded at 28 °C. In contrast, Mannino et al. [30] investigated the effect of sea temperature seasonal variation on the TPC of C. amentacea. They harvested algae once in every season (winter, spring, summer and autumn) and measured the sea temperature. The authors observed the highest TPC in winter (0.8% DW) when the sea temperature was the lowest. In summer and autumn, when the sea temperatures were above 20 °C, the TPCs were the lowest, 0.4 and 0.37% DW, respectively. In their study, the TPC values showed a negative correlation with sea temperature. Cystoseira compressa extracts, from Urla (Turkey) [31], were screened for TPC, total flavonoid content (TFC), antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. The highest TPC of 1.5 mg GAE/g and TFC of 0.8 mg QE/g were found for hexane extract while the antioxidant activity of the hexane extract measured by DPPH radical inhibition was only 21.2%, more than four-fold lower than results in our study for hydroalcoholic extracts. In comparison, the methanolic extracts (similar polarity like ethanol) showed the TPC and TFC of 0.2 mg GAE/g and 0.3 mg QE/g, respectively and two-fold lower DPPH inhibition.

Abu-Khudir et al. [18] evaluated the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities of cold methanolic extract, hot methanolic extract, cold aqueous extract, and hot aqueous extract from C. crinita and Sargassum linearifolium. The highest TPC was found for the cold methanolic extract of C. crinita, 15.0 ± 0.58 mg GAE/g of dried extract, which is more than two-fold lower than the amount detected in the September extract from our study which contained the lowest TPC. The authors also found a high content of fatty acids (44%) and their esters in C. crinita cold methanolic extract. Both seaweeds showed similar DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity with C. crinita cold methanolic extract having IC50 of 125.6 µg/mL and 254.8 µg/mL, respectively. De La Fuente et al. [32] extracted C. amentacea var. stricta with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 50% ethanol for determining TPC, TFC and antioxidant activity of extracts by DPPH radical scavenging, FRAP, OH scavenging, and nitric oxide (NO) scavenging methods. The TPC and TFC of DMSO extracts were 65.9 µg GAE/mg and 15.8 µg QE/mg, 3.2- and 5.1-fold higher than ethanolic extracts. Similar to our results, both investigated extracts had DPPH radical scavenging activity higher than 90%. Furthermore, the DMSO extracts showed a reducing activity of almost 90% while ethanolic extract showed a higher OH radical scavenging activity. Both extracts showed very low cytotoxicity, enabling their possible use as nutraceuticals.

Oucif et al. [20] screened six seaweed species (including C. compressa and C. stricta) for TPC, DPPH radical scavenging activity and reducing power. The highest TPCs were found for C. compressa methanolic and ethanolic extracts, 10.24 ± 0.09 and 15.70 ± 0.72 mg GAE/g DW, respectively. Cystoseira compressa ethanol extract had over 90% inhibition activity for DPPH radical and the highest reducing power, which can be compared with our results. Mhadhebi et al. [24] determined TPC, DPPH and FRAP in C. crinita, C. sedoides and C. compressa extracts. Among the three alga, C. compressa extract had the highest TPC of 61.0 mg GAE/g, which is comparable to our results, the lowest DPPH IC50 of 12.0 µg/mL, and the highest FRAP value, 2.6 mg GAE/g.

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity

The results of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the C. compressa extracts against common foodborne pathogens are shown in Table 2. Gram-positive bacteria were more susceptible to seaweed extracts than Gram-negative bacteria. The lowest MIC results were found against L. monocytogenes, for June, July, and August samples with the lowest MBC in June, and against S. aureus in July and August with the same MBC. There was no difference in MIC and MBC values for E. coli among the investigated months. June, July, and August extracts had the lowest MIC values for S. enteritidis. The results showed higher antimicrobial activity from June to August when the sea temperature was the highest, against all bacteria.

Table 2.

Results of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC, mg/mL) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC, mg/mL) of the seaweed extracts against foodborne pathogens (n = 3).

| May | June | July | August | September | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| Escherichia coli | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | >10 |

| Salmonella enteritidis | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | >10 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 10 | >10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | >10 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10 | >10 | 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 |

| Bacillus cereus | >10 | n.d. | 10 | >10 | 10 | >10 | 10 | >10 | >10 | n.d. |

n.d.—not determined

Alghazeer et al. [33] performed microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) on P. pavonica and C. compressa. Flavonoid-rich extracts (110.92 ± 11.38 mg rutin equivalents /g for C. compressa) were tested for antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates of S. aureus subsp. aureus, Bacillus pumilus, B. cereus, Salmonella enterica subsp. enteric, and enterohemorrhagic E. coli using the well diffusion method, MIC and MBC. Cystoseira compressa extract showed stronger antibacterial activity than P. pavonica with inhibition zones against 14 tested isolates. The largest inhibition zones were 20.5 mm for S. aureus and B. cereus, 31 mm for S. enterica and 17 mm for E. coli. Furthermore, C. compressa extract had the lowest MIC (31.25 μg/mL) and MBC (62.5 μg/mL) values against S. aureus and S. enterica. Against B. cereus, it had an MIC value of 62.5 μg/mL and an MBC value of 125 μg/mL. The highest MIC (125 μg/mL) and MBC (500 μg/mL) values were found against E. coli. Maggio et al. [28] evaluated the antibacterial activity of eight brown seaweeds, six belonging to the genus Cystoseira (including C. compressa) and two belonging to the Dictyotaceae family, against E. coli, Kocuria rhizophila, S. aureus and a toxigenic and MDR S. aureus using the disk diffusion method. None of the seaweed extracts inhibited the growth of E. coli. Cystoseira compressa and Carpodesmia amentacea extracts showed antibacterial activity against K. rhizophila, S. aureus and MDR S. aureus. Abdeldjebbar et al. [34] tested the antibacterial effect of C. compressa and P. pavonica acetonic extracts against E. coli and S. aureus. The antibacterial activity was measured by disk diffusion method and MIC determination. Cystoseira compressa extract had 14 mm inhibition diameter for E. coli, showing better antibacterial activity than P. pavonica (12 mm). However, MIC values were not detected for C. compressa against both bacteria. Padina pavonica extract had an MIC of 50 µL for tested strains. Both extracts had a 10 mm inhibition diameter for S. aureus. The authors also tested the synergy of these two extracts at a 1:1 ratio. The mixture showed significant synergistic effect against E. coli and S. aureus with 16 and 12 mm inhibition diameters, respectively. The antibacterial activity of a C. crinita cold methanolic extract was evaluated by the disk diffusion method [18]. The extract showed the highest inhibition zones for E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus and Streptococcus aureus, with 10.5, 12.8, 10.2, 12.6, 13.3 and 11.2 mm, respectively.

Cystoseira compressa extracts [31] showed moderate activity against E. coli, S. aureus, Streptococcus epidermidis, E. faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella pneumonie, B. cereus and P. aeruginosa. In this study, the authors found the lowest MIC value of 32 µg/mL for both methanolic extract against S. epidermidis and chloroform extract against E. cloacae. Dulger and Dulger [21] tested C. compressa water and ethanol extracts against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Ethanol extract had the lowest MIC of 3.2 mg/mL and MBC of 6.3 mg/mL.

In the above-mentioned studies, the chemical content of the investigated algae was not correlated with the antimicrobial activity, however, it is evident that Cystoseira spp. shows some potential to be used nutraceuticals and therapeutic purposes.

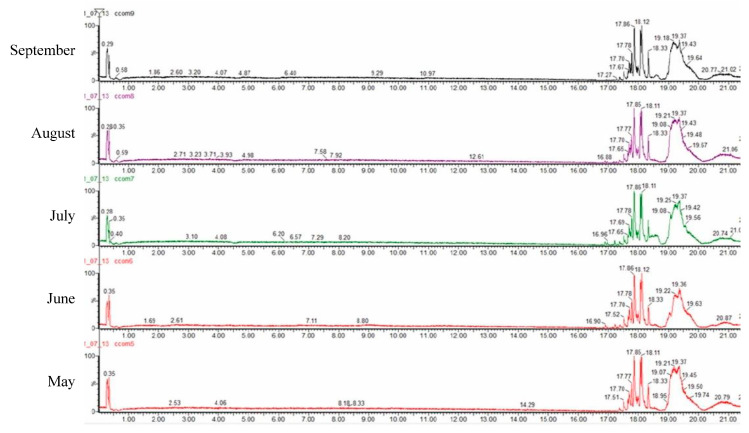

2.3. Chemical Analysis by UPLC-PDA-ESI-QTOF

A quali-quantitative analysis of the polar compounds from C. compressa extracts was achieved by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis in negative ion mode. The base peak chromatograms obtained are shown in Figure 3. A total of 49 compounds were identified and the results are shown in Table 3, along with their retention time, observed and theoretical m/z, error (ppm), score (%), molecular formulae and in source fragments. In all cases, the score remained higher than 90% and the error lower than 5 ppm. All the compounds we tentatively identified according to Bouafif et al. [35] who previously found most of them in Cystoseira and PubChem database. Furthermore, the amount of each compound is expressed as a percentage calculated based in the areas for each extract.

Figure 3.

Chromatograms of the HPLC-qTOF-MS analyses of C. compressa.

Table 3.

The compounds detected in investigated C. compressa samples analyzed by UPLC-PDA-ESI-QTOF.

| N° | RT (min) | Observed (m/z) | Theorical (m/z) | Error (ppm) | Score (%) | Molecular Formula | In Source Fragments |

Tentative Compound | May (%) | June (%) | July (%) | August (%) | September (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.28 | 343.0367 | 343.0368 | −0.3 | 94.18 | C20H4N6O | - | 1a,9b-Dihydrophenanthro [9,10-b]oxirene-2,3,4,7,8,9-hexacarbonitrile | 4.76 | 4.50 | 4.54 | 4.96 | 6.51 |

| 2 | 0.29 | 201.0244 | 201.0247 | −1.5 | 98.89 | C4H10O9 | - | 2-(1,2,2,2-Tetrahydroxyethoxy)ethane-1,1,1,2-tetrol | 6.67 | 6.17 | 6.58 | 6.72 | 7.90 |

| 3 | 0.32 | 141.0162 | 141.0161 | 0.7 | 91.01 | C2H2N6O2 | - | Diazidoacetic acid | 1.97 | 2.02 | 2.40 | 2.01 | 1.74 |

| 4 | 0.35 | 181.0707 | 181.0712 | −2.8 | 100 | C6H14O6 | 101.0230; 89.0227; 71.0137; 59.0121 | d-Sorbitol | 3.11 | 3.57 | 1.34 | 2.34 | 1.83 |

| 5 | 0.40 | 317.0506 | 317.0509 | −0.9 | 90.44 | C12H14O10 | 209.0890 | d-glucaric acid derivate | 1.13 | 0.88 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.80 |

| 6 | 0.42 | 384.1510 | 384.1519 | −2.3 | 92.29 | C15H23N5O7 | - | Threonyl-histidyl-glutamic acid | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| 7 | 16.56 | 287.2211 | 287.2222 | −3.8 | 95.91 | C16H32O4 | - | 10,11-Dihydroxy-9,12-dioxooctadecanoic acid | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| 8 | 16.90 | 275.1999 | 275.2011 | −4.4 | 96.48 | C18H28O2 | 231.2098; 253.0915 | Stearidonic acid (C18:4n-3) isomer a | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.06 |

| 9 | 16.97 | 275.2007 | 275.2011 | −1.5 | 97.68 | C18H28O2 | 231.2092; 177.0854; 255.2322; | Stearidonic acid (C18:4n-3) isomer b | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.08 |

| 10 | 16.97 | 293.2112 | 293.2117 | −1.7 | 92.64 | C18H30O3 | 249.1835; 275.1652 | 13-ketooctadecadienoic acid isomer a | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.13 |

| 11 | 17.08 | 287.2211 | 287.2222 | −3.8 | 95.91 | C16H32O4 | 271.2083; 253.2157 | 10,16-Dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid isomer a | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 12 | 17.13 | 309.2056 | 309.2066 | −3.2 | 96.09 | C18H30O4 | 279.2287 | 6,9-Octadecadienedioic acid | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 13 | 17.18 | 295.2276 | 295.2273 | 1.0 | 100 | C18H32O3 | 279.2300; 275.2019; 255.2325 | 9,10-Epoxyoctadecenoic acid (vernolic acid) | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| 14 | 17.20 | 277.2159 | 277.2168 | −3.2 | 91.36 | C18H30O2 | 255.2321; 239.2030; 227.2013 | gamma-Linolenic acid isomer a (C18:3n-6) | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.08 |

| 15 | 17.22 | 429.3009 | 429.3005 | 0.9 | 91.64 | C27H42O4 | 273.1859; 135.0447 | 24-Keto-1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 16 | 17.26 | 247.1689 | 247.1698 | −3.6 | 94.96 | C16H24O2 | 233.0985 | 2,4,6-Triisopropyl benzoic acid | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| 17 | 17.35 | 287.2212 | 287.2222 | −3.5 | 90.62 | C16H32O4 | 271.2082; 253.2158 | 10,16-Dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid isomer b | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| 18 | 17.37 | 199.1694 | 199.1698 | −2.0 | 90.11 | C12H24O2 | 181.1062; 155.0336 | Lauric acid | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| 19 | 17.38 | 297.2426 | 297.2430 | −1.3 | 98.84 | C18H34O3 | 279.2367; 255.2334 | 10-Oxooctadecanoic acid isomer a | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| 20 | 17.40 | 243.1952 | 243.1960 | −3.3 | 90.78 | C14H28O3 | 197.1907 | 3-hydroxymyristic acid | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| 21 | 17.42 | 293.2112 | 293.2117 | −1.7 | 94.2 | C18H30O3 | 249.1833; 275.1649 | 13-ketooctadecadienoic acid isomer b | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.04 |

| 22 | 17.43 | 427.2827 | 427.2848 | −4.9 | 90.28 | C27H40O4 | 271.1716; 188.0842; 135.0441 | Hydroxyprogesterone caproate | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 23 | 17.46 | 429.3009 | 429.3005 | 0.9 | 91.64 | C27H42O4 | 273.1843; 135.0445 | 24-Keto-1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 isomer b | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.01 | n.d. |

| 24 | 17.48 | 295.2262 | 295.2273 | −3.7 | 94.13 | C18H32O3 | 279.2295; 275.2023; 255.2321 | 9,10-Epoxyoctadecenoic acid isomer b (vernolic acid) | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.41 |

| 25 | 17.51 | 269.2110 | 269.2117 | −2.6 | 98.63 | C16H30O3 | 251.2336 | 3-Oxohexadecanoic acid | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.11 |

| 26 | 17.51 | 225.1857 | 225.1855 | −0.9 | 95.99 | C14H26O2 | 188.0832; 213.1870; 175.0757 | Myristoleic acid | 2.35 | 2.14 | 2.26 | 2.15 | 2.22 |

| 27 | 17.53 | 255.2319 | 255.2324 | −2.0 | 91.41 | C16H32O2 | 225.1861; 213.1845 | Hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid) isomer a (C16:0) | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 28 | 17.57 | 275.2007 | 275.2011 | −1.5 | 97.68 | C18H28O2 | 231.2093; 255.2326 | Stearidonic acid (C18:4n-3) isomer c | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.33 |

| 29 | 17.58 | 277.2152 | 277.2168 | −5.8 | 99.51 | C18H30O2 | 255.2289; 239.2001; 227.1989 | gamma-Linolenic acid isomer b (C18:3n-6) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 30 | 17.59 | 213.18458 | 213.1855 | −3.6 | 92.41 | C13H26O2 | - | Tridecanoic acid | 1.20 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.15 |

| 31 | 17.62 | 427.2839 | 427.2848 | −2.1 | 96.07 | C27H40O4 | 271.1659; 188.0827; 135.0442 | Hydroxyprogesterone caproate isomer b | n.d. | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 32 | 17.62 | 257.2108 | 257.2117 | −3.5 | 95.16 | C15H30O3 | 227.2037; 211.2072 | 11-Hydroxypentadecanoic acid | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| 33 | 17.63 | 251.2010 | 251.2011 | −0.4 | 100 | C16H28O2 | 233.9910; 207.0983 | 7,10-hexadecadienoic acid | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

| 34 | 17.64 | 297.2429 | 297.2430 | −0.3 | 97.33 | C18H34O3 | 279.2364; 255.2332 | 10-Oxooctadecanoic acid isomer b | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.56 |

| 35 | 17.66 | 239.2001 | 239.2011 | −4.2 | 97.7 | C15H28O2 | 227.2002; 159.8926 | Myristoleic acid methyl ester | 5.22 | 5.23 | 5.00 | 4.89 | 4.92 |

| 36 | 17.74 | 277.2162 | 277.2168 | −2.2 | 99.51 | C18H30O2 | 255.2318; 239.1991; 227.2015 | gamma-Linolenic acid isomer c (C18:3n-6) | 1.08 | 1.41 | 1.92 | 2.47 | 2.17 |

| 37 | 17.71 | 301.2158 | 301.2168 | −3.3 | 99.56 | C20H30O2 | 283.2283; 275.1972 | Eicosapentanoic acid isomer a (C20:5n-3) | 0.65 | 0.65 | 1.09 | 0.81 | 0.75 |

| 38 | 17.73 | 301.2156 | 301.2168 | −4.0 | 98.12 | C20H30O2 | 283.2287; 275.1957 | Eicosapentanoic acid isomer b (C20:5n-3) | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.06 | 0.80 | 0.74 |

| 39 | 17.77 | 227.2001 | 227.2011 | −4.4 | 93.6 | C14H28O2 | - | Tetradecanoic acid (C14:0) | 5.04 | 5.19 | 5.34 | 5.17 | 5.22 |

| 40 | 17.81 | 271.2266 | 271.2273 | −2.6 | 97.75 | C16H32O3 | 253.0954; 225.2211 | Hydroxy-palmitic acid | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.66 |

| 41 | 17.85 | 253.2156 | 253.2168 | −4.7 | 96.47 | C16H30O2 | - | Palmitoleic acid isomer a (C16:1n-7) | 12.65 | 11.93 | 11.45 | 11.57 | 11.74 |

| 42 | 17.94 | 241.2170 | 241.2168 | 0.8 | 100 | C15H30O2 | 223.2081 | Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) | 3.68 | 3.89 | 3.87 | 3.72 | 3.67 |

| 43 | 17.97 | 279.2314 | 279.2324 | −3.6 | 98.25 | C18H32O2 | 267.2340; 275.2037 | Octadeca-10,12-dienoic acid (C18:2n-6) | 1.07 | 1.14 | 1.29 | 1.31 | 1.27 |

| 44 | 18.01 | 267.2318 | 267.2324 | −2.2 | 99.96 | C17H32O2 | 249.0437; 223.0291 | 9-Heptadecenoic acid (C17:1n-8) | 3.73 | 3.99 | 3.67 | 3.78 | 3.60 |

| 45 | 18.08 | 255.2321 | 255.2324 | −1.2 | 99.9 | C16H32O2 | 227.2015 | Hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid)(C16:0) | 10.46 | 10.46 | 10.24 | 9.92 | 9.83 |

| 46 | 18.12 | 281.2486 | 281.2481 | 1.8 | 96.88 | C18H34O2 | - | Oleic acid (C18:1n-9) | 15.87 | 15.06 | 15.39 | 15.33 | 15.12 |

| 47 | 18.22 | 269.2476 | 269.2481 | −5.6 | 99.96 | C17H34O2 | 255.2325 | Heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) | 5.30 | 5.23 | 5.18 | 5.08 | 4.95 |

| 48 | 18.33 | 283.2618 | 283.2637 | −1.9 | 99.21 | C18H36O2 | - | Octadecanoic acid (stearic acid) C18:0 | 5.44 | 4.92 | 5.01 | 5.11 | 5.24 |

| 49 | 18.54 | 311.2944 | 311.2950 | −2.0 | 90.87 | C20H40O2 | 255.2307; 225.0060 | Arachidic acid | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.68 |

The most dominant compound tentatively identified was oleic acid (C18:1n-9) with a content more than 15% in all tested samples, highest in May. The other two dominant compounds were palmitoleic acid (C16:1n-7) and palmitic acid (C16:0) also showing highest content in the May extract. Except for highly represented fatty acids, ω-3 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) was also found, with the highest content in July.

Low molecular weight phenolic compounds were not identified. This does not confirm that the phenolics are not present, but the main phenolics in algae are probably present as tannins (phlorotannins) that cannot be determined by HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS because they cannot be ionized due to their high molecular weight. Maggio et al. [28] reported citric acid, isocitric acid, vanillic acid methyl ester, vanillic acid sulfate, gallic acid, dihydroxybenzoic acid, 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-(2-hydroxyphenoxy)-hexa-2,4-dienoate, phloracetophenone, bromo-phloroglucinol, vanillylmandelic acid and exifone in C. compressa. The compounds were identified without quantification. Previously, vanilic acid, hydroxybenzoic acid, gallocatechin, carnosic acid, phloroglucinol, and hydroxytyrosol 4-O-glucoside were identified as main phenolics in fucoidan algae Sargassum sp. [36].

Jerković et al. [37] investigated fucoidal brown alga Fucus virsoides and found 42.28% oleic acid, 15.00% arachidonic acid and 10.51% myristic acid in its fatty acid composition. The authors used high performance liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-HRMS) to determine the composition of less polar non-volatile compounds. The major compounds tentatively identified belonged to five groups, steroids, terpenoids, fatty acid glycerides, carotenoids, and chlorophyll derivatives. Fatty acid glycerides were dominant, which is comparable to our study.

Ristivojević et al. [38] identified the bioactive compounds responsible for the radical scavenging and antimicrobial activities of Undaria pinnatifida and Saccharina japonica methanolic extracts using the high-performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC)-bioautography assay and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-LTQ-MS/MS combined. They reported eicosapentaenoic, stearidonic and arachidonic acids as major compounds accountable for these activities. Their findings are in accordance with previous reports on PUFAs having antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses and fungi [39,40].

PUFAs, such as EPA, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and linolenic acid (LNA), showed in vitro antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori, S. aureus, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), Vibrio vulnificus, and Streptococcus mutans, inhibiting bacterial growth or altering their cell morphology [40]. To deactivate microbial cells, PUFAs directly affected the cell membranes, enhanced free radical generation, and increased the formation of cytotoxic lipid peroxides and their bioactive metabolites increasing the leukocytes’ and macrophages’ phagocytic action [39]. EPA and DHA extracts showed antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogenic bacteria, L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis, Enterobacter aerogenes, E. coli, S. aureus, S. enteritidis, S. typhimurium, and P. aeruginosa [41]. The authors reported the lowest MIC value of 250 µg/mL for DHA extract against P. aeruginosa. A low MIC value of 350 µg/mL was found for EPA extract against L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis and P. aeruginosa, and for DHA extract against L. monocytogenes and B. subtilis. Besides, Cvitković et al. [42] investigated the extraction of lipid fractions from C. compressa, C. barbata, F. virsoides, and Codium bursa. In agreement with our results, the dominant fatty acids in all seaweeds were palmitic, oleic and linolenic fatty acids. Cystoseira compressa and C. barbata had the highest amounts of omega-3 EPA and DHA. Cystoseira compressa had 20.35% oleic acid, 17.66% arachidonic acid, 14.86% linoleic acid, 11.92% palmitic acid and 8.72% linolenic acid. Bacteria S. aureus can be inhibited by most free fatty acids: Lacey and Lord [43] seeded this bacterium on human skin and then applied LNA to the skin which resulted in the rapid death of the seeded bacteria. EPA (C20:5n-3) was found to successfully inhibit the growth of S. aureus and B. cereus with a 64 mg/L MIC value [44]. Oleic acid was confirmed in vitro and in vivo to effectively eliminate MRSA by disrupting its cell wall [45].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

Cystoseira compressa samples were collected off the south coast of the island Čiovo in the Adriatic Sea from May to September 2020 (43.493389° N, 16.272505° E). Sampling was done throughout a lagoon at 25 points in a depth range of 20 to 80 cm. The sea temperature and salinity were measured during sampling using a YSI Pro2030 probe (Yellow Springs, OH, USA). A sample of this species is deposited in the herbarium at the University Department of Marine Studies in Split.

3.2. Pre-Treatment and Extraction

Prior to the extraction, harvested algal samples were washed with tap water to remove epiphytes. Samples were then freeze-dried (FreeZone 2.5, Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) and ground. Based on the previous research [46] seaweeds were extracted using MAE in the advanced microwave extraction system (ETHOS X, Milestone Srl, Sorisole, Italy). Seaweeds were mixed with 50% ethanol, using 1:10 (w:v) algae to solvent ratio and extracted for 15 min at 200 W and 60 °C. The extracts were further centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 8 min at room temperature and the supernatant was filtered. The ethanolic solvent was evaporated at 50 °C and the rest of the extracts freeze dried.

3.3. Determination of Total Phenolics, Total Tannins and Antioxidant Activity

The crude algal extracts were dissolved in 50% ethanol prior to analyses in the concentration of 20 mg/mL. Folin–Ciocalteu method [47] was used for determining the TPC. Briefly, 25 μL of the extract was mixed with 1.5 mL distilled water and 125 μL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. The solution was stirred and 375 μL 20% sodium carbonate solution and 475 μL distilled water was added after one minute. Samples were left in the dark at room temperature for 2 h. The absorbance was read using a spectrophotometer (SPECORD 200 Plus, Edition 2010, Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) at 765 nm. Results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents in mg/g of freeze-dried extract (mg GAE/g).

The TTC was measured according to Zhong et al. [36] with some modifications. Briefly, 25 µL of the sample, 150 µL 4% (w/v) ethanolic vanillin solution, and 25 µL 32% sulfuric acid (diluted with ethanol) were added to the 96-well plate and mixed. The plate was incubated for 15 min at room temperature and absorbance was read at 500 nm using the microplate reader (Synergy HTX Multi-Mode Reader, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The TTC results were expressed as mg catechin equivalents per g of dried extract (mg CE/g).

The reducing activity was measured as FRAP (ferric reducing/antioxidant power) [48]. Briefly, 300 μL of FRAP reagent solution was pipetted into the microplate wells, and absorbance at 592 nm was recorded. Then, 10 μL of the sample was added to the FRAP reagent and the change in absorbance after 4 min was measured. The change in absorbance, calculated as the difference between the final value of the absorbance of the reaction mixture after a certain reaction time (4 min) and the absorbance of FRAP reagent before sample addition, was compared with the values obtained for the standard solutions of Trolox. Results were expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalents per liter of extract (μM TE).

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging ability of extracts was also measured in 96-well microplates [49]. DPPH radical solution with the initial absorbance of 1.2 (290 μL) was pipetted into microplate wells, and absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Then, 10 μL of the sample was added to the wells and the decrease in the absorbance was measured after 1 h using the plate reader. The antioxidant activity of extracts was expressed as DPPH radical inhibition percentages (% inhibition).

The oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) method [50,51] was performed to determine the antioxidant capacity of extracts by monitoring the inhibition of the action of free peroxyl radicals formed by the decomposition of 2,2-azobis (2-methylpropionamide)-dihydrochloride (AAPH) against the fluorescent compound fluorescein. Briefly, 150 μL of fluorescein and 25 μL of the sample in 1:200 dilution (or Trolox in the case of standard compound, or puffer in the case of blank) were pipetted into microplate wells and thermostated for 30 min at 37 °C. After 30 min, 25 μL of AAPH was added and measurements were performed at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 520 nm every minute for 80 min. The results were expressed as μM of Trolox Equivalents (μM TE).

3.4. Determination of the Antimicrobial Activity

The foodborne pathogens Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13076, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, and Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 were used in this study.

The microdilution method was used to determine the extracts’ MICs against foodborne pathogens. The extracts were dissolved in 4% DMSO (10 mg/mL) and diluted with Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB). Then, 100 µL of the mixture was added to the first well of the 96-well microtiter plate. Two-fold dilutions were done in the next wells (10–0.16 mg/mL). The 50 µL of prepared inoculum (1 × 105 colony forming units (CFU)/mL determined by using the growth curves of bacteria in the log phase) was added to each well and plates were mixed on a microtiter plate shaker for 1 min at 600 rpm (Plate Shaker-Thermostat PST-60 HL, Biosan, Riga, Latvia). Positive control (50 µL of inoculum and 50 µL of broth media), negative control (50 µL of broth media and 50 µL of extract), blank (100 µL of broth media) and 4% DMSO were also tested. After 24 h of incubation, 20 µL of the indicator of bacterial metabolic activity, 2-p-iodophenyl-3-p-nitrophenyl-5-phenyl tetrazolium chloride (INT, in 2 mg/mL concentration) was added to each well. Plates were mixed on a plate shaker and incubated for 1 h in the dark. MIC values were read visually as the lowest concentration of the extract at which there was no detection of bacterial growth seen as the reduction of INT to red formazan [52].

MBC of the seaweed extracts was determined as the lowest concentration at which no microbial growth was detected on agar plates after subcultivation of bacterial suspension pipetted from wells where MIC was determined and from wells with higher extract concentrations [53].

3.5. Compound Analysis by UPLC-PDA-ESI-QTOF

Dried extract (3 mg) of algae was dissolved in 1 mL of MeOH/H2O 1/1 v/v. The analysis of compounds from algae was carried out with the use of an ACQUITY Ultra Performance LC system equipped with a photodiode array detector with a binary solvent manager (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) series with a mass detector Q/TOF micro mass spectrometer (Waters) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in negative mode at the following conditions: capillary voltage, 2300 kV; source temperature, 100 °C; cone gas flow, 40 L/h; desolvation temperature, 500 °C; desolvation gas flow, 11,000 L/h; and scan range, m/z 50–1500. Separation of individual compounds was carried out using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH Shield RP18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) at 40 °C. The elution gradient test was carried out using water containing 1% acetic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B), and applied as follows: 0 min, 1% B; 2.3 min, 1% B; 4.4 min, 7% B; 8.1 min, 14% B; 12.2 min, 24% B; 16 min, 40% B; 18.3 min, 100% B, 21 min, 100% B; 22.4 min, 1% B; 25 min, 1% B. The sample volume injected was 2 μL and the flow rate used was 0.6 mL/min. The compounds were monitored at 280 nm. Integration and data elaboration were performed using MassLynx 4.1 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) [54].

3.6. Statistical Analyses

The results of antioxidant analyses were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and antimicrobial results as a mean of 3 replicas. Analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to assess the difference between TPC, TTC and antioxidant assays, followed by a least significance difference test at 95% confidence level to evaluate differences between sets of mean values [55]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the relation between the variables. Analyses were carried out using Statgraphics Centurion-Ver.16.1.11 (StatPoint Technologies, Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA).

4. Conclusions

The results obtained for the brown fucoidal macroalgae C. compressa from the Adriatic Sea indicated that it was a good source of compounds. The TPC and TTC content reflected a variation over the growing season, with the highest values in June. The detected FRAP showed high correlation with TPC and TTC content. The DPPH values were >80% inhibition over the whole sampling period, while the highest antioxidant activity with regards to ORAC was in August when the sea temperature was the highest. No evident correlation existed between the temperature and salinity change and TPC, TTC or antioxidant activity. From June to August, higher antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens was observed, especially against L. monocytogenes, S. aureus and S. enteritidis. Further investigations are needed to gain insight into the effect of abiotic factors, growth and thallus development of the alga on its biological potential and to discover the compounds responsible for the different biological activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ivan Šimat from Centaurus d.o.o., Solin for administrative support and technical help during the investigations and Matilda Šprung for technical help during antimicrobial analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Š. and G.T.; methodology, M.Č., D.S., V.V. and D.B.; validation, D.S. and D.B.; formal analysis M.Č., D.S., R.F., I.G.M., D.B. and M.d.C.R.-D.; resources, V.Š., D.B. and V.V.; data curation, M.Č., D.S., R.F., I.G.M., D.B. and M.d.C.R.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Č. and V.Š.; writing—review and editing, V.Š., G.T., I.G.M. and V.V.; supervision, V.Š. and D.S.; project administration, V.Š. and G.T.; funding acquisition, V.Š., D.B. and V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the PRIMA program under project BioProMedFood (Project ID 1467). The PRIMA programme is supported by the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Generalić Mekinić I., Skroza D., Šimat V., Hamed I., Čagalj M., Perković Z.P. Phenolic Content of Brown Algae (Pheophyceae) Species: Extraction, Identification, and Quantification. Biomolecules. 2019;9:244. doi: 10.3390/biom9060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannino A.M., Micheli C. Ecological Function of Phenolic Compounds from Mediterranean Fucoid Algae and Seagrasses: An Overview on the Genus Cystoseira Sensu Lato and Posidonia Oceanica (L.) Delile. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020;8:19. doi: 10.3390/jmse8010019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiger-Pouvreau V., Jégou C., Cérantola S., Guérard F., Le Lann K. Phlorotannins in Sargassaceae Species from Brittany (France) In: Bourgougnon N., editor. Advances in Botanical Research. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2014. pp. 379–411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina C., Renda G., Laudicella V., Trepos R., Fauchon M., Hellio C., Santulli A. From Ecology to Biotechnology, Study of the Defense Strategies of Algae and Halophytes (from Trapani Saltworks, NW Sicily) with a Focus on Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:881. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelhamid A., Jouini M., Bel Haj Amor H., Mzoughi Z., Dridi M., Ben Said R., Bouraoui A. Phytochemical Analysis and Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antinociceptive Potential of Phlorotannin-Rich Fractions from Three Mediterranean Brown Seaweeds. Mar. Biotechnol. 2018;20:60–74. doi: 10.1007/s10126-017-9787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Šimat V., Elabed N., Kulawik P., Ceylan Z., Jamroz E., Yazgan H., Čagalj M., Regenstein J.M., Özogul F. Recent Advances in Marine-Based Nutraceuticals and Their Health Benefits. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:627. doi: 10.3390/md18120627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno de Sousa C., Gangadhar K.N., Macridachis J., Pavão M., Morais T.R., Campino L., Varela J., Lago J.H.G. Cystoseira Algae (Fucaceae): Update on Their Chemical Entities and Biological Activities. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2017;28:1486–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orellana S., Hernández M., Sansón M. Diversity of Cystoseira Sensu Lato (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) in the Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Based on Morphological and DNA Evidence, Including Carpodesmia Gen. Emend. and Treptacantha Gen. Emend. Eur. J. Phycol. 2019;54:447–465. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2019.1590862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S., Sahoo D., Levine I. Assessment of Nutritional Value in a Brown Seaweed Sargassum Wightii and Their Seasonal Variations. Algal Res. 2015;9:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Praiboon J., Palakas S., Noiraksa T., Miyashita K. Seasonal Variation in Nutritional Composition and Anti-Proliferative Activity of Brown Seaweed, Sargassum Oligocystum. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018;30:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10811-017-1248-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosch B.J., Paul N.A., de Nys R., Magnusson M. Seasonal and Within-Plant Variation in Fatty Acid Content and Composition in the Brown Seaweed Spatoglossum Macrodontum (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) J. Appl. Phycol. 2015;27:387–398. doi: 10.1007/s10811-014-0308-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancuso F.P., Messina C.M., Santulli A., Laudicella V.A., Giommi C., Sarà G., Airoldi L. Influence of Ambient Temperature on the Photosynthetic Activity and Phenolic Content of the Intertidal Cystoseira Compressa along the Italian Coastline. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019;31:3069–3076. doi: 10.1007/s10811-019-01802-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britton D., Schmid M., Revill A.T., Virtue P., Nichols P.D., Hurd C.L., Mundy C.N. Seasonal and Site-Specific Variation in the Nutritional Quality of Temperate Seaweed Assemblages: Implications for Grazing Invertebrates and the Commercial Exploitation of Seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021;33:603–616. doi: 10.1007/s10811-020-02302-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karkhaneh Yousefi M., Seyed Hashtroudi M., Mashinchian Moradi A., Ghassempour A.R. Seasonal Variation of Fucoxanthin Content in Four Species of Brown Seaweeds from Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2020;19:2394–2408. doi: 10.22092/ijfs.2020.122396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marinho G.S., Sørensen A.D.M., Safafar H., Pedersen A.H., Holdt S.L. Antioxidant Content and Activity of the Seaweed Saccharina Latissima: A Seasonal Perspective. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019;31:1343–1354. doi: 10.1007/s10811-018-1650-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vizetto-Duarte C., Pereira H., De Sousa C.B., Rauter A.P., Albericio F., Custódio L., Barreira L., Varela J. Fatty Acid Profile of Different Species of Algae of the Cystoseira Genus: A Nutraceutical Perspective. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015;29:1264–1270. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.992343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Custódio L., Silvestre L., Rocha M.I., Rodrigues M.J., Vizetto-Duarte C., Pereira H., Barreira L., Varela J. Methanol Extracts from Cystoseira Tamariscifolia and Cystoseira Nodicaulis Are Able to Inhibit Cholinesterases and Protect a Human Dopaminergic Cell Line from Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Cytotoxicity. Pharm. Biol. 2016;54:1687–1696. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1123278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Khudir R., Ismail G.A., Diab T. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Tumor Activities of Sargassum Linearifolium and Cystoseira Crinita from Egyptian Mediterranean Coast. Nutr. Cancer. 2021;73:829–844. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1764069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Generalić Mekinić I., Čagalj M., Tabanelli G., Montanari C., Barbieri F., Skroza D., Šimat V. Seasonal Changes in Essential Oil Constituents of Cystoseira Compressa: First Report. Molecules. 2021;26:6649. doi: 10.3390/molecules26216649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oucif H., Adjout R., Sebahi R., Boukortt F.O., Ali-Mehidi S., El S.-M., Abi-Ayad A. Comparison of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Some Selected Seaweeds from Algerian West Coast. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2017;16:1474–1480. doi: 10.5897/AJB2017.16043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dulger G., Dulger B. Antibacterial Activity of Two Brown Algae (Cystoseira Compressa and Padina Pavonica) against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2014;4:918–923. doi: 10.9734/BMRJ/2014/10449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mhadhebi L., Dellai A., Clary-Laroche A., Said R.B., Robert J., Bouraoui A. Anti-Inflammatory and Antiproliferative Activities of C. Compressa. Drug Dev. Res. 2012;73:82–89. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosanić M., Ranković B., Stanojković T. Biological Potential of Marine Macroalgae of the Genus Cystoseira. Acta Biol. Hung. 2015;66:374–384. doi: 10.1556/018.66.2015.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mhadhebi L., Mhadhebi A., Robert J., Bouraoui A. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antiproliferative Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Three Mediterranean Brown Seaweeds of the Genus Cystoseira. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2014;13:207–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermund D.B. Bioactive Seaweeds for Food Applications. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. Antioxidant Properties of Seaweed-Derived Substances; pp. 201–221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobsen C., Sørensen A.D.M., Holdt S.L., Akoh C.C., Hermund D.B. Source, Extraction, Characterization, and Applications of Novel Antioxidants from Seaweed. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;10:541–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-032818-121401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polat S., Trif M., Rusu A., Šimat V., Čagalj M., Alak G., Meral R., Özogul Y., Polat A., Özogul F. Recent Advances in Industrial Applications of Seaweeds. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021:1–30. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.2010646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maggio A., Alduina R., Oddo E., Piccionello A.P., Mannino A.M. Antibacterial Activity and HPLC Analysis of Extracts from Mediterranean Brown Algae. Plant Biosyst. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2020.1829737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falace A., Zanelli E., Bressan G. Morphological and Reproductive Phenology of Cystoseira Compressa (Esper) Gerloff & Nizamuddin (Fucales, Fucophyceae) in the Gulf of Trieste (North Adriatic) Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2005;5:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mannino A.M., Vaglica V., Cammarata M., Oddo E. Effects of Temperature on Total Phenolic Compounds in Cystoseira Amentacea (C. Agardh) Bory (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) from Southern Mediterranean Sea. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2016;150:152–160. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2014.941033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Güner A., Köksal Ç., Erel Ş.B., Kayalar H., Nalbantsoy A., Sukatar A., Karabay Yavaşoğlu N.Ü. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities with Acute Toxicity, Cytotoxicity and Mutagenicity of Cystoseira Compressa (Esper) Gerloff & Nizamuddin from the Coast of Urla (Izmir, Turkey) Cytotechnology. 2015;67:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De La Fuente G., Fontana M., Asnaghi V., Chiantore M., Mirata S., Salis A., Damonte G., Scarfì S. The Remarkable Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of the Extracts of the Brown Alga Cystoseira Amentacea Var. Stricta. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:2. doi: 10.3390/md19010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alghazeer R., Elmansori A., Sidati M., Gammoudi F., Azwai S., Naas H., Garbaj A., Eldaghayes I. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoid Extracts of Two Selected Libyan Algae against Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria Isolated from Food Products. J. Biosci. Med. 2017;5:26–48. doi: 10.4236/jbm.2017.51003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdeldjebbar F.Z., Bennabi F., Ayache A., Berrayah M., Tassadiat S. Synergistic Effect of Padina Pavonica and Cystoseira Compressa in Antibacterial Activity and Retention of Heavy Metals. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2021;11:36–40. doi: 10.15421/2021_196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouafif C., Messaoud C., Boussaid M., Langar H. Fatty Acid Profile of Cystoseira C. Agardh (Phaeophyceae, Fucales) Species from the Tunisian Coast: Taxonomic and Nutritional Assessments. Ciencias Mar. 2018;44:169–183. doi: 10.7773/cm.v44i3.2798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong B., Robinson N.A., Warner R.D., Barrow C.J., Dunshea F.R., Suleria H.A.R. LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Characterization of Seaweed Phenolics and Their Antioxidant Potential. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:331. doi: 10.3390/md18060331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jerković I., Cikoš A.-M., Babić S., Čižmek L., Bojanić K., Aladić K., Ul’yanovskii N.V., Kosyakov D.S., Lebedev A.T., Čož-Rakovac R., et al. Bioprospecting of Less-Polar Constituents from Endemic Brown Macroalga Fucus Virsoides J. Agardh from the Adriatic Sea and Targeted Antioxidant Effects In Vitro and In Vivo (Zebrafish Model) Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:235. doi: 10.3390/md19050235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ristivojević P., Jovanović V., Opsenica D.M., Park J., Rollinger J.M., Velicković T.Ć. Rapid Analytical Approach for Bioprofiling Compounds with Radical Scavenging and Antimicrobial Activities from Seaweeds. Food Chem. 2021;334:127562. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das U.N. Arachidonic Acid and Other Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Some of Their Metabolites Function as Endogenous Antimicrobial Molecules: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2018;11:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chanda W., Joseph T.P., Guo X.F., Wang W.D., Liu M., Vuai M.S., Padhiar A.A., Zhong M.T. Effectiveness of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids against Microbial Pathogens. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2018;19:253–262. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1700063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin S.Y., Bajpai V.K., Kim H.R., Kang S.C. Antibacterial Activity of Bioconverted Eicosapentaenoic (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) against Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;113:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cvitković D., Dragović-Uzelac V., Dobrinčić A., Čož-Rakovac R., Balbino S. The Effect of Solvent and Extraction Method on the Recovery of Lipid Fraction from Adriatic Sea Macroalgae. Algal Res. 2021;56:102291. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2021.102291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lacey R.W., Lord V.L. Sensitivity of Staphylococci to Fatty Acids: Novel Inactivation of Linolenic Acid by Serum. J. Med. Microbiol. 1981;14:41–49. doi: 10.1099/00222615-14-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le P., Desbois A. Antibacterial Effect of Eicosapentaenoic Acid against Bacillus Cereus and Staphylococcus Aureus: Killing Kinetics, Selection for Resistance, and Potential Cellular Target. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:334. doi: 10.3390/md15110334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen C.-H., Wang Y., Nakatsuji T., Liu Y.-T., Zouboulis C.C., Gallo R.L., Zhang L., Hsieh M.-F., Huang C.-M. An Innate Bactericidal Oleic Acid Effective against Skin Infection of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: A Therapy Concordant with Evolutionary Medicine. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;21:391–399. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1011.11014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Čagalj M., Skroza D., Tabanelli G., Özogul F., Šimat V. Maximizing the Antioxidant Capacity of Padina Pavonica by Choosing the Right Drying and Extraction Methods. Processes. 2021;9:587. doi: 10.3390/pr9040587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amerine M.A., Ough C.S. Methods for Analysis of Musts and Wines. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benzie I.F.F., Strain J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996;239:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milat A.M., Boban M., Teissedre P.L., Šešelja-Perišin A., Jurić D., Skroza D., Generalić-Mekinić I., Ljubenkov I., Volarević J., Rasines-Perea Z., et al. Effects of Oxidation and Browning of Macerated White Wine on Its Antioxidant and Direct Vasodilatory Activity. J. Funct. Foods. 2019;59:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prior R.L., Hoang H., Gu L., Wu X., Bacchiocca M., Howard L., Hampsch-Woodill M., Huang D., Ou B., Jacob R. Assays for Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORACFL)) of Plasma and Other Biological and Food Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:3273–3279. doi: 10.1021/jf0262256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burčul F., Generalić Mekinić I., Radan M., Rollin P., Blažević I. Isothiocyanates: Cholinesterase Inhibiting, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activity. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018;33:577–582. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1442832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skroza D., Šimat V., Smole Možina S., Katalinić V., Boban N., Generalić Mekinić I. Interactions of Resveratrol with Other Phenolics and Activity against Food-Borne Pathogens. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;7:2312–2318. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elez Garofulić I., Malin V., Repajić M., Zorić Z., Pedisić S., Sterniša M., Smole Možina S., Dragović-Uzelac V. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Capacity and Antimicrobial Activity of Nettle Leaves Extracts Obtained by Advanced Extraction Techniques. Molecules. 2021;26:6153. doi: 10.3390/molecules26206153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verni M., Pontonio E., Krona A., Jacob S., Pinto D., Rinaldi F., Verardo V., Díaz-de-Cerio E., Coda R., Rizzello C.G. Bioprocessing of Brewers’ Spent Grain Enhances Its Antioxidant Activity: Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Bioactive Peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1831. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Šimat V., Vlahović J., Soldo B., Generalić Mekinić I., Čagalj M., Hamed I., Skroza D. Production and Characterization of Crude Oils from Seafood Processing by-Products. Food Biosci. 2020;33:100484. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2019.100484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.