Abstract

The gene encoding the entire Babesia equi merozoite antigen 1 (EMA-1) was inserted into a baculovirus transfer vector, and a recombinant virus expressing EMA-1 was isolated. The expressed EMA-1 was transported to the surface of infected insect cells, as judged by an indirect fluorescent-antibody test (IFAT). The expressed EMA-1 was also secreted into the supernatant of a cell culture infected with recombinant baculovirus. Both intracellular and extracellular EMA-1 reacted with a specific antibody in Western blots. The expressed EMA-1 had an apparent molecular mass of 34 kDa that was identical to that of native EMA-1. The secreted EMA-1 was used as an antigen in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA differentiated B. equi-infected horse sera from Babesia caballi-infected horse sera or normal horse sera. The ELISA was more sensitive than the complement fixation test and IFAT. These results demonstrated that the recombinant EMA-1 expressed in insect cells might be a useful diagnostic reagent for detection of antibodies to B. equi.

Babesia equi is a tick-borne hemoprotozoan parasite that causes piroplasmosis in horses. Equine piroplasmosis is an economically important disease that is characterized by fever, anemia, and icterus and that is mostly prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas as well as in temperate climatic zones (15). Areas of endemicity include many parts of Europe, Africa, Arabia, and Asia (15). Due to the almost worldwide distribution of various tick vectors, the introduction of a carrier into areas of nonendemicity should be prevented.

The complement fixation test (CFT) and indirect fluorescent-antibody test (IFAT) have commonly been used to detect B. equi infection. However, these serologic tests are generally restricted by the antibody detection limits and cross-reactivity (4, 5). Besides CFT and IFAT, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with B. equi lysate antigen has been used for detection of antibodies to B. equi (19). However, the ELISA is hindered by a limited antigen supply and poor specificity (4, 5, 19).

Merozoite antigen 1 (EMA-1) is the major surface protein of B. equi (8). It is considered an important candidate with which to develop a diagnostic reagent for detection of antibodies to B. equi (9, 10). A competitive inhibition ELISA (CI-ELISA) that can detect antibodies to B. equi based on a monoclonal antibody to EMA-1 has been developed by Knowles et al. (11), who demonstrated that it can be more sensitive than CFT in detecting antibodies to B. equi. The CI-ELISA offers the advantage of a high degree of specificity but the disadvantage of the requirement of a complicated operating procedure. Therefore, there is a need to develop a simple ELISA method.

Here, we established a highly specific, sensitive, and simple ELISA method using recombinant EMA-1 expressed in insect cells by baculovirus. Our data indicated that the recombinant baculovirus-expressed EMA-1 should be a useful diagnostic reagent for detection of antibodies to B. equi in horses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite.

The B. equi USDA strain was cultured in equine erythrocytes as described previously (2, 3). When the level of B. equi parasitemia reached 10 to 20%, cultured erythrocytes were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation, and then the pellets were stored at −80°C.

Cloning of EMA-1 gene.

B. equi-infected erythrocytes were washed with PBS and lysed in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 M NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA. They were then digested with proteinase K (100 μg/ml) for 2 h at 55°C. The DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The pellets were resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) and used as a template DNA for PCR. Two oligonucleotide primers (5′-ACGGATCCCAAGATGATTTCC-3′ and 5′-ACGGATCCGTCACTTAGTAAA-3′) were used to amplify the EMA-1 gene by PCR. The amplified DNA was inserted into the BamHI site of the pUC19 vector. The resulting plasmid was designated pUCEMA-1.

Construction of recombinant baculovirus.

The EMA-1 gene was recovered from pUCEMA-1 after digestion with BamHI and was then ligated into the BamHI site of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcNPV) transfer vector pBacPAK8 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells were cotransfected with recombinant transfer vector pBEMA-1 and linear AcNPV viral DNA (Pharmigen, San Diego, Calif.) by using the lipofectin reagent (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). After 4 days of incubation at 27°C, the culture supernatant containing recombinant virus was harvested and plaque purified. The expression of EMA-1 in the plaques was confirmed by IFAT with anti-EMA-1 serum produced in mice immunized with recombinant EMA-1 expressed in Escherichia coli. Positive plaque was selected, and after three cycles of purification a recombinant baculovirus (AcEMA-1) was obtained.

ELISA.

Sf9 cells infected with AcEMA-1 (10 PFU/cell) were cultured in protein-free Sf-900 medium for 4 days. The culture medium containing secreted EMA-1 was harvested and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 h to remove the baculovirus. The supernatant was dialyzed against antigen coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer [pH 9.6]) and was then used for the ELISA. The antigen diluted in coating buffer (50 μl) was dispensed into the wells of flat-bottom 96-well microplates. After incubation at 4°C for 24 h, the unadsorbed antigen was discarded and 100 μl of blocking solution (PBS containing 3% skim milk) was added to the wells. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the blocking solution was discarded and 50 μl of test serum diluted in blocking solution was added to each well. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the plate was washed three times with wash solution (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20) and was then incubated with 50 μl of horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-horse immunoglobulin G antibody diluted in blocking solution per well at 37°C for 1 h. The plates were washed three times with wash solution, and then 100 μl of substrate [0.1 M citric acid, 0.2 M sodium phosphate, 0.003% H2O2, 0.5 mg of 2,2′-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate) per ml] was added to each well. The absorbance at 415 nm was read after 1 h, and the ELISA titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the maximum dilution that showed an ELISA value equal to or greater than 0.1, which is the difference in absorbance between that for the EMA-1 antigen well and that for the control antigen (LacZ) well.

Immunization of mice with secreted EMA-1.

Ten micrograms of the secreted EMA-1 in Freund's complete adjuvant was intraperitoneally injected into mice (BALB/c mice; age, 8 weeks). The same antigen in Freund's incomplete adjuvant was intraperitoneally injected into the mice on day 14 and again on day 28. Sera from immunized mice were collected 10 days after the last immunization.

Sera.

Serum samples from horses experimentally infected with either B. equi or Babesia caballi and negative serum samples from healthy horses were obtained from the Equine Research Institute, the Japan Racing Association, and Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute. Ten of horse serum samples that were imported from the People's Republic of China and that were positive for Babesia parasites in blood smears or for Babesia antibodies as tested by CFT were obtained from the Yokohama Animal Quarantine Service, Ministry of Agriculture, Forest and Fishery (13, 17). Sera from 142 horses from areas of endemicity in central Mongolia were also examined.

IFAT.

CFT.

CFT was performed as described previously (13).

Western blot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot proceeded as described previously (21).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the EMA-1 gene of the B. equi USDA strain has been submitted to the DDBJ database under accession no. AB043618.

RESULTS

Cloning of EMA-1 gene from B. equi USDA.

The gene encoding EMA-1 of B. equi was amplified from the USDA strain by PCR. The predicted 819-bp fragment was amplified from B. equi DNA but was not amplified from either B. caballi DNA or horse leukocyte DNA (data not shown). The PCR product was inserted into pUC19 and then sequenced. An open reading frame of 819 nucleotides, capable of encoding a translation product of 272 amino acids, was identified (GenBank accession no. AB043618). The predicted amino acid sequence of the EMA-1 gene of the USDA strain was compared with those of the EMA-1 genes of other strains of B. equi (Table 1). EMA-1 of the USDA strain shared a high degree of homology (80 to 99%) with the EMA-1 genes of all other strains isolated from various countries.

TABLE 1.

Homology of amino acid sequences between EMA-1 from strain USDA and EMA-1 from other strains of B. equi

| Strain | GenBank accession no. | No. of amino acid residues | Homology with USDA

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Identity | % Similarity | |||

| USDA | AB043618 | 272 | 100 | 0 |

| Brazil | U97167 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| Florida | L13784 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| Morocco | U97168 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| Russia | AB015211 | 272 | 94 | 3 |

| 212 | AB015212 | 272 | 80 | 7 |

| CA | AB015214 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| D-8 | AB015218 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| D-16 | AB015219 | 272 | 93 | 5 |

| D-31 | AB015220 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| E12 | AF261824 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| E15 | AF255730 | 272 | 99 | 0 |

| H-25 | AB015208 | 272 | 88 | 8 |

| LR | AB015213 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| Q-1 | AB015210 | 272 | 98 | 2 |

| Q-6 | AB015209 | 272 | 83 | 8 |

| VRY-2 | AB015216 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

| VRY-4 | AB015215 | 272 | 92 | 5 |

| VRY-5 | AB015217 | 272 | 93 | 4 |

Expression of EMA-1 in insect cells by recombinant baculovirus.

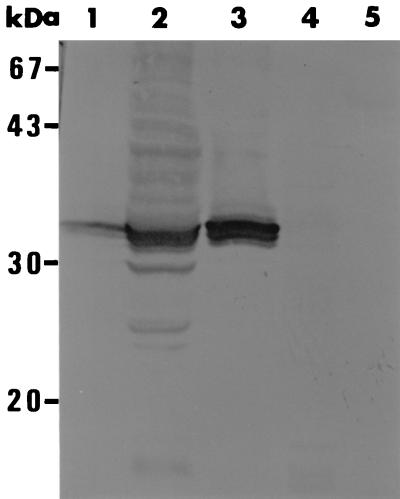

Sf9 cells were infected at 10 PFU/cell with a recombinant baculovirus carrying the EMA-1 gene (AcEMA-1), constructed as described above, or with a control recombinant baculovirus carrying the lacZ gene (AcLacZ) (20). After incubation for 4 days, cell extracts and culture media were tested by Western blotting with anti-EMA-1 serum. Figure 1 shows that anti-EMA-1 serum reacted to a major band with a molecular mass of 34 kDa in both the AcEMA-1-infected cell extract and its medium (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3). The molecular mass of recombinant EMA-1 was identical to that of native EMA-1 isolated from B. equi-infected erythrocytes (Fig. 1, lane 1). In contrast, no band was detected in the AcLacZ-infected cell extract or its culture medium (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 5).

FIG. 1.

Western blots of recombinant EMA-1 expressed in insect cells using mouse anti-EMA-1 serum. Lane 1, B. equi-infected erythrocytes; lane 2, AcEMA-1-infected cells; lane 3, AcEMA-1-infected cell culture media; lane 4, AcLacZ-infected cells; lane 5, AcLacZ-infected cell culture media.

To determine whether the EMA-1 expressed by the recombinant virus was transported to the cell surface, the cells infected with AcEMA-1 were examined by IFAT (data not shown). Specific fluorescence was observed in fixed and unfixed Sf9 cells that had been infected with AcEMA-1. Fluorescence was undetectable in AcLacZ- or mock-infected cells. These results indicated that the EMA-1 expressed by AcEMA-1 is transported to the cell surface.

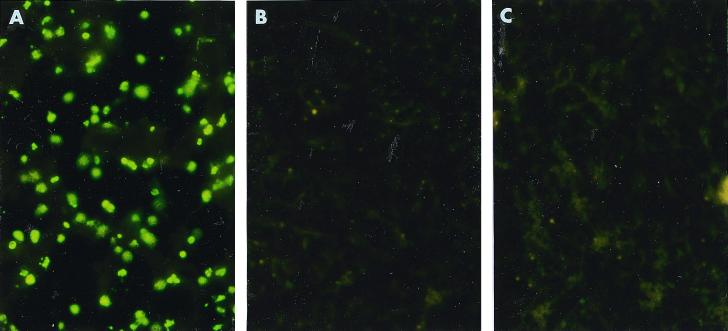

To determine the immunogenicity of the expressed EMA-1, mice were immunized with secreted EMA-1. The antiserum reacted with B. equi but did not react with either B. caballi or horse erythrocytes (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

IFAT analysis of anti-B. equi antibody produced in mice immunized with recombinant EMA-1 expressed in insect cells. B. equi-infected horse erythrocytes (A), B. caballi-infected horse erythrocytes (B), and mock-infected horse erythrocytes (C) were reacted with mouse antiserum.

Diagnosis of B. equi infection in horses by ELISA with recombinant EMA-1 as antigen.

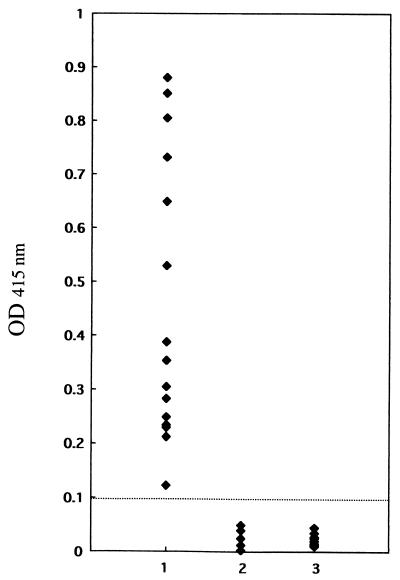

To evaluate whether the recombinant EMA-1 expressed by baculovirus can be an antigen suitable for use in the diagnosis of B. equi infection in horses, the secreted EMA-1 was tested in an ELISA. Figure 3 shows that all serum samples from 15 horses experimentally infected with B. equi were positive (optical densities, >0.1), whereas serum samples from 10 healthy horses and 5 horses experimentally infected with B. caballi were negative (optical densities, <0.1).

FIG. 3.

Values from ELISA with recombinant EMA-1 and experimentally infected horse sera. Lane 1, B. equi-infected horse sera; lane 2, B. caballi-infected horse sera; lane 3, noninfected horse sera. OD, optical density.

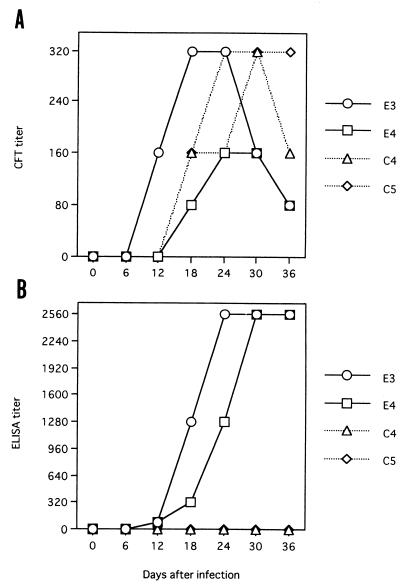

Sequential serum or erythrocyte samples from horses experimentally infected with B. equi and B. caballi were analyzed by ELISA, CFT, and determination of parasites on thin blood films (Fig. 4). Antibody to EMA-1 was detected at 12 to 36 days postinfection (d.p.i.) by ELISA in both horses infected with B. equi but not in two horses infected with B. caballi. The ELISA antibody titers increased during the period of positivity (Fig. 4A). Antibodies to B. equi were detected at 12 to 36 and 18 to 36 d.p.i. by CFT in horses E3 and E4, respectively (Fig. 4B). The CFT antibody titers decreased from 24 or 30 d.p.i. B. equi merozoites were observed only at 6 to 12 and 12 d.p.i. in horses E3 and E4, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Antibody responses to recombinant EMA-1 in B. equi-infected horses. Sequential serum samples from horses experimentally infected with B. equi (horses E3 and E4) or B. caballi (horses C4 and C5) were tested by CFT (A) and ELISA (B).

Serum samples from 10 field horses positive for B. equi in blood smears were tested by ELISA and CFT or IFAT, and the results were compared. Table 2 shows that 4 (40%), 7 (70%), and 9 (90%) of 10 samples were positive by CFT, IFAT, and ELISA, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Serological comparison of horse sera positive for B. equi in blood smears by ELISA, CFT, and IFAT

| Serum sample no. (horse no.) | CFT titer (result) | IFAT titer (result) | ELISA titer (result) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (EI-2) | 10 (+) | 80 (+) | 640 (+) |

| 2 (EI-5) | <5 (−) | <80 (−) | 80 (+) |

| 3 (EI-13) | 10 (+) | 80 (+) | 2,560 (+) |

| 4 (EI-17) | <5 (−) | <80 (−) | 80 (+) |

| 5 (EI-24) | <5 (−) | 320 (+) | 5,120 (+) |

| 6 (EI-25) | <5 (−) | 160 (+) | 2,560 (+) |

| 7 (EI-32) | <5 (−) | 80 (+) | 2,560 (+) |

| 8 (EI-39) | 40 (+) | 320 (+) | 10,240 (+) |

| 9 (EI-46) | <5 (−) | <80 (−) | <80 (−) |

| 10 (EI-49) | 10 (+) | 160 (+) | 1,280 (+) |

Serum samples collected from 142 field horses in central Mongolia were investigated by ELISA. Although no parasites were detected in the Giemsa-stained blood smears from any of 142 horses, 127 of 142 (89%) samples were positive by ELISA (Table 3). The ages of the positive horses varied from months to 20 years. The age-related prevalence is consistent with an increasing probability of exposure over time, but because parasites were not detected by blood smears, one cannot exclude the possibility that many of the animals had cleared the infection.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of B. equi infection in central Mongolian horses at various ages

| Age (yr) | No. (%) of horses

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Seropositive | Seronegative | |

| <1 | 5 | 6 |

| 1–5 | 29 | 2 |

| 6–10 | 56 | 6 |

| 11–15 | 32 | 1 |

| 16–20 | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 127 (89) | 15 (11) |

DISCUSSION

During the host-parasite interaction, the surface proteins of parasite cells are the main targets of host immune responses, and the surface antigens of the parasites are therefore logical targets for use as subunit vaccines and diagnostic reagents. The major surface protein of B. equi, EMA-1, has good antigenicity and potential as a diagnostic reagent for detection of antibodies to B. equi (8, 9, 10, 11). In the present study, we expressed the EMA-1 gene of B. equi in insect cells using a recombinant baculovirus and evaluated its diagnostic potential by ELISA.

The gene encoding EMA-1 of B. equi was cloned from strain USDA isolated in the United States (18). The predicted amino acid sequence of EMA-1 of strain USDA shared a high degree of homology with those of all other strains isolated from various countries. This indicated that EMA-1 should be a suitable subunit vaccine or diagnostic candidate for detection of antibodies to B. equi. In addition, the predicted amino acid sequence of EMA-1 of strain USDA appeared to contain a signal sequence, a transmembrane region, and an N-linked glycosylation site, as seen in another strain (8).

The EMA-1 produced in insect cells by recombinant baculovirus was transported to the cell surface, as seen in the B. equi parasite. Although the EMA-1 had a typical membrane protein structure, as described above, some EMA-1 was secreted into the supernatant of recombinant baculovirus-infected cell culture. It is not yet clear why the EMA-1 was secreted into cell culture medium. One explanation is that the mechanism by which proteins anchor to the cell membrane differs between parasite and insect cells. Further studies are required to determine the factor(s) that causes secretion of EMA-1 in insect cells. Both intracellular and extracellular EMA-1 reacted with B. equi-infected horse serum in Western blots (data not shown). The expressed EMA-1 had an apparent molecular mass of 34 kDa, which was identical to that of native EMA-1. These results indicated that the EMA-1 expressed in insect cells is similar to native EMA-1 in structure and antigenicity.

To evaluate whether EMA-1 expressed in insect cells by recombinant baculovirus is suitable for use in immunodiagnostic assays for B. equi infection in horses, we tested the secreted EMA-1 by ELISA. This test differentiated between B. equi-infected horse sera and B. caballi-infected horse sera or healthy horse sera. The ELISA was more sensitive than CFT and IFAT. These results demonstrated that the recombinant EMA-1 expressed in insect cells should be a useful diagnostic reagent for detection of antibodies to B. equi.

Secreted EMA-1 offers two advantages over the intracellular EMA-1. The preparation of secreted EMA-1 is simple, and it overcomes the problem of contamination with proteins from insect cells or baculovirus.

The baculovirus expression system is a popular means of expressing foreign genes mainly from other viruses. In general, the immunization of laboratory animals or natural host animals with antigens produced by baculoviruses induced neutralizing antibodies and protected the animals from challenge with corresponding viruses. Recently, the baculovirus expression system has been used to express foreign genes from protozoan parasites, and animals immunized with recombinant antigens produced in insect cells developed protective immunity against virulent parasite infections (1, 6, 7, 12, 14, 16). In the present study, mice inoculated with the recombinant EMA-1 expressed by baculovirus developed high titers of antibody against blood merozoites of B. equi. To date, the potential immunity of EMA-1 in horses has not been investigated. Our next project will be to implement immunization trials with horses to determine the potency of the recombinant EMA-1 produced in insect cells as a potential subunit vaccine with which to control B. equi infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Kanemaru of the Equine Research Institute, the Japan Racing Association, and D. T. de Waal of the Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute for providing horse sera.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders R F, Crewther P E, Edwards S, Margetts M, Matthew M L, Pollock B, Pye D. Immunisation with recombinant AMA-1 protects mice against infection with Plasmodium chabaudi. Vaccine. 1998;16:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)88331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avarazed A, DeWaal D T, Igarashi I, saito A, Oyamada T, Toyoda Y, Suzuki N. Prevalence of equine piroplasmosis in central Mongolia. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1997;64:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avarazed A, Igarashi I, DeWaal D T, Kawai S, Oomori Y, Inoue N, Maki Y, Omata Y, Saito A, Nagasawa H, Toyoda Y, Suzuki N. Monoclonal antibody against Babesia equi: characterization and potential application of antigen for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1835–1839. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1835-1839.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose R, Jorgensen W K, Dalgliesh R J, Friedhoff K T, de Vos A J. Current state and future trends in the diagnosis of babesiosi. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:61–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruning A. Equine piroplasmosis: an update on diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Br Vet J. 1996;152:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(96)80070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S P, Case S E, Gosnell W L, Hashimoto A, Kramer K J, Tam L Q, Hashiro C Q, Nikaido C M, Gibson H L, Lee-Ng C T, Barr P J, Yokota B T, Hut G S. A recombinant baculovirus 42-kilodalton C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 protects Aotus monkeys against malaria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:253–261. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.253-261.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X G, Fuag M C, Ma X, Peng H J, Shen S M, Liu G Z. Baculovirus expression of the major surface antigen of Toxoplasma gondii and the immune response of mice injected with the recombinant P30. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappmeyer L S, Perryman L E, Knowles D P. A Babesia equi gene encodes a surface protein with homology to Theileria species. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowles D P, Kappmeyer L S, Stiller D, Hennager S G, Perryman L E. Antibody to a recombinant merozoite protein epitope identified horses infected with Babesia equi. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3122–3126. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3122-3126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles D P, Perryman L E, Goff W L, Miller C D, Harrington R D, Gorham J R. A monoclonal antibody defines a geographically conserved surface protein epitope of Babesia equi merozoites. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2412–2417. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2412-2417.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles D P, Perryman L E, Kappmeyer L S, Hennager S G. Detection of equine antibody to Babesia equi merozoite proteins by a monoclonal antibody-based competitive inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2056–2058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.2056-2058.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nene V, Inumaru S, McKeever D, Morzaria S, Shaw M, Musoke A. Characterization of an insect cell-derived Theileria parva sporozoite vaccine antigen and immunogenicity in cattle. Infect Immun. 1995;63:503–508. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.503-508.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimaniwa M, Iwasaki S, Sakakibara M, Morino S, Nakayama N, Yoshida K, Abe T, Ando N, Hayashibara H, Hasegawa M, Yamashiro T. Equine piroplasmosis detected in horses imported from China. J Anim Protozooses. 1991;2:20–30. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perera K L, Handunnetti S M, Holm I, Longacre S, Mendis K. Baculovirus merozoite surface protein 1 C-terminal recombinant antigens are highly protective in a natural primate model for human Plasmodium vivax malaria. Infect Immun. 1988;66:1500–1506. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1500-1506.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schein E. Equine babesiosis. In: Ristic M, editor. Babesiosis of domestic animals and man. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y P, Hasnain S E, Sacci J B, Holloway B P, Fujioka H, Kumar N, Wohlhueter R, Hoffman S L, Collins W E, Lai A A. Immunogenicity and in vitro protective efficacy of a recombinant multistage Plasmodium falciparum candidate vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1615–1620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki N, Igarashi I, Abgaandorjiin A, DeWaal D T, Nagasawa H, Omata Y, Saito A, Oyamada T. Preliminary survey on horse serum indirect fluorescence antibody titers in Japan against Babesia equi and Babesia caballi (Onderstepoort strain) antigen. J Protozool Res. 1996;6:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenter A M, Friedhoff K T. Serodiagnosis of experimental and natural Babesia equi and B. caballi infections. Vet Parasitol. 1986;20:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(86)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiland G. Species-specific serodiagnosis of equine piroplasma infections by means of complement fixation test (CFT), immunofluorescence (IIF), and enzyme-liked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Vet Parasitol. 1986;20:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(86)90091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xuan X, Nakamura T, Ihara T, Sato I, Tuchiya K, Nosetto E, Ishihama A, Ueda S. Characterization of pseudorabies virus glycoprotein gII expressed by recombinant baculovirus. Virus Res. 1995;36:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)00112-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xuan X, Maeda K, Mikami T, Otsuka H. Characterization of canine herpesvirus glycoprotein C expressed in insect cells. Virus Res. 1996;46:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]