Abstract

Background

Mast cells are key players in innate immunity and the TH2 adaptive immune response. The latter counterbalances the TH1 response, which is critical for antiviral immunity. Clonal mast cell activation disorders (cMCADs, such as mastocytosis and clonal mast cell activation syndrome) are characterized by abnormal mast cell accumulation and/or activation. No data on the antiviral immune response in patients with MCADs have been published.

Objective

To study a comprehensive range of outcomes in patients with cMCAD with PCR- or serologically confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 and to characterize the specific anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) immune response in this setting.

Methods

Clinical follow-up and outcome data were collected prospectively over a 12-month period by members of the French Centre de Référence des Mastocytoses rare disease network. Anti–SARS-CoV-2–specific T-cell activity was measured with an ELISA, and humoral responses were evaluated by assaying circulating levels of specific IgG, IgA, and neutralizing antibodies.

Results

Overall, 32 patients with cMCAD were evaluated. None required noninvasive or mechanical ventilation. Two patients were admitted to hospital for oxygen and steroid therapy. The SARS-CoV-2–specific immune response was characterized in 21 of the 32 patients. Most had high counts of circulating SARS-CoV-2–specific, IFN-γ–producing T cells and high titers of neutralizing antispike IgGs. The patients frequently showed spontaneous T-cell IFN-γ production in the absence of stimulation; this production was correlated with basal circulating tryptase levels (a marker of the mast cell burden).

Conclusions

Patients with cMCADs might not be at risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019, perhaps due to their spontaneous production of IFN-γ.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Mast cells, Mastocytosis, Clonal mast cell activation syndrome, Mast cell activation disorders, T cells, B cells

Abbreviations used: AFIRMM, Association Française pour les Initiatives de Recherche sur le Mastocyte et les Mastocytose; CEREMAST, Centre de Référence des Mastocytoses; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; cMCAD, clonal mast cell activation disorder; ELISpot, enzyme-linked immunospot; IQR, interquartile range; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; MMAS, monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome; NK, natural killer; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SFC, spot-forming cell

What is already known about this topic? Mast cells are key players in the TH2 immune response but not in antiviral immune responses. Data on antiviral responses (and especially responses against coronaviruses) in patients with clonal mast cell activation disorders have not previously been reported.

What does this article add to our knowledge? In a comprehensive, prospective study, we did not observe any cases of severe coronavirus disease 2019 among groups of patients with clonal mast cell activation disorders. The patients showed effective anticoronavirus immune responses. Spontaneous IFN-γ release (in the absence of T-cell stimulation) was observed frequently in patients with clonal mast cell activation disorders and was correlated with the basal tryptase level.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? The observed spontaneous production of IFN-γ (correlated with the mast cell burden) suggests that mast cells have a role in the antiviral immune response. The 4 patients with serial serologic measurements became seronegative over time. Hence, anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination after coronavirus disease 2019 is strongly recommended in patients with clonal mast cell activation disorders.

Introduction

Clonal mast cell activation disorders (cMCADs) constitute a heterogeneous disease spectrum that ranges from monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (MMAS) to mastocytosis and is characterized by the pathological activation and/or accumulation of mast cells (MCs).1 In adults, the most frequent cMCAD is indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM). Advanced mastocytosis (including aggressive systemic mastocytosis, MC leukemia, and systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematological neoplasm) is rarer and is linked to a poor prognosis.2 , 3

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a potentially fatal, pandemic infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).4 A body of compelling pathophysiological data suggests that interferons have a major role in disease control. These include type I interferon (produced by plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and type III interferon (IFN-γ) produced by T cells from the adaptive immune system in the early and late phases of the disease, respectively.5, 6, 7, 8

One can hypothesize that the MCs’ ability to drive TH2 responses9, 10, 11 (which counterbalance TH1 responses) might impair antiviral immunity in patients with cMCADs. Furthermore, histamine blocks the in vitro activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells; in vivo, this might weaken antiviral immune responses.12 MCs might therefore (1) contribute to COVID-19–induced inflammation by releasing proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF and (2) exacerbate COVID-19 lung damage via degranulation.13 , 14 If so, this would render patients with cMCAD more susceptible to severe COVID-19.

Over a 12-month period, members of the French Centre de Référence des Mastocytoses (CEREMAST) rare disease network collected data prospectively on the patients with cMCADs (MMAS and mastocytosis) and a positive PCR test result or serology assay for SARS-CoV-2. Here, we describe the patients’ clinical course, outcomes, and immunologic characteristics.

Methods

Patients

The members of the CEREMAST network collected data prospectively from patients with a cMCAD and COVID-19, as documented by either a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result on a nasal swab or symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 and a positive anti–SARS-CoV-2 serology assay. Patients with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 but who lacked a positive PCR test result or a positive serology assay for SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded from the study. The study data were covered cases recorded between February 1, 2020, and February 1, 2021. cMCADs were diagnosed according to the 2016 World Health Organization classification.1 , 15

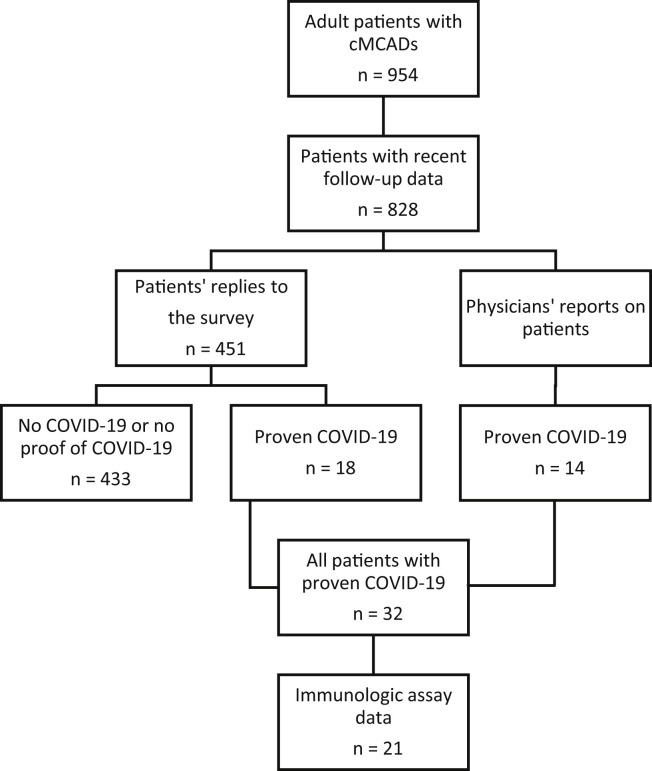

First, we sent a questionnaire to all adult patients (18 years or older) with mastocytosis or MMAS and for whom recent follow-up data were available in the CEREMAST national registry (n = 828) and who were participating in a study sponsored by the Association Française pour les Initiatives de Recherche sur le Mastocyte et les Mastocytose (AFIRMM). The questionnaire was designed to collect data on any signs of MC activation displayed during COVID-19, the patient’s treatments, and the patient’s specific signs and outcomes related to COVID-19. We then classified the patients as having had proven COVID-19 or not (Figure 1 ). Subsequently, we surveyed all members of the CEREMAST network (n = 24) and thereby collected data on patients who had presented with COVID-19 but had not replied to the questionnaire. To check that we had not missed any severe cases (at least in the greater Paris region, as a proxy for national coverage), we also searched the French national hospital discharge database (Programme de médicalisation des systèmes d'information) for patients with cMCAD admitted for COVID-19 to hospitals in the Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris (the Paris Public Hospital Group, which treats 8.3 million patients a year). All patients with confirmed COVID-19 were assayed for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. To characterize the anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune response, patients included in the AFIRMM register were asked to provide a blood sample (for serology testing) during a follow-up consultation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the selection of patients with cMCADs and proven COVID-19.

For the experiment on spontaneous IFN-γ production, we incorporated a control group of patients with idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) and who had either experienced mild to moderate COVID-19 (n = 2) or had no history of COVID-19 (n = 9). MCAS was diagnosed according to the modified European Competence Network on Mastocytosis guidelines.16 An increase in the serum total tryptase level by at least 20% above baseline plus 2 ng/mL during or within 4 hours of a symptomatic period was not investigated in most patients.

To measure the spontaneous production of IFN-γ in the ELISpot assay, we studied PBMCs from patients with cMCADs and MCAS (with and without a history of COVID-19) and healthy donors with a history of COVID-19.

Ethic statements

All the patients with cMCADs were followed up in CEREMAST mastocytosis network reference centers and were enrolled in a prospective, nationwide, multicenter study sponsored by AFIRMM. The AFIRMM study was approved by the local investigational review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France, France; reference: 93-00) and was carried out in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients gave their written informed consent to participation. The patients’ blood samples were obtained as part of routine follow-up care for their cMCADs. Data on the control cohorts were collected prospectively and analyzed as part of the COVID-HOP study (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04418375; other study identifier: APHP200609).

Immunologic assays

SARS-CoV-2–specific T-cell responses were evaluated by measuring the cells’ IFN-γ production in an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay. Briefly, PBMCs were isolated from fresh blood collected during a follow-up consultation. After isolation on a Ficoll density gradient, the PBMCs were stimulated for 18 to 20 hours with individual 15-mer 11-aa overlapping peptide pools for various SARS-CoV-2 proteins or common coronavirus proteins. Each responding cell generated a spot. The ELISpot results were expressed as the number of spot-forming cells (SFCs)/106 CD3+ T cells after the subtraction of background values from wells with nonstimulated cells.

The negative controls were PBMCs cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with l-glutamine, sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, Molsheim, France), and 10% human AB serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France), in the absence of stimulation. The positive controls were PHA (Sigma-Aldrich) and the CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool (JPT Peptide Technologies GmbH, BioNTech AG, Berlin, Germany). The tested SARS-CoV-2 peptide pools were derived from a peptide scan through the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (2 pools: S1 for the N-terminal fragment and S2 for the C-terminal fragment), membrane protein (M), nucleoprotein (N), envelope small membrane protein (E), and ORF3a protein. We also tested peptide pools derived from the spike glycoprotein of the common human alpha-coronaviruses (HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63) and beta-coronaviruses (HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1).

The humoral immune response (including the production of antispike SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgA antibodies and the neutralizing ability of antispike IgGs) was characterized using previously described S-flow and S-pseudotype neutralization assays.17 Briefly, the S-flow assay used human embryonic kidney 293T cells transduced with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Cells were incubated with sera from patients (dilution: 1:300) and stained with either anti-IgG or anti-IgA antibodies. The fluorescent signal was measured by flow cytometry. For the S-pseudotype neutralization assay, pseudotyped viruses carrying SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were used. The viral pseudotypes were incubated with the sera to be tested (dilution: 1:100), added to transduced human embryonic kidney 293T cells expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. The assay measures the anti-S antibodies’ ability to neutralize an infection, as described elsewhere.17

Non-cMCAD control groups

For each group, the number of patients, the median age, and the sex ratio are reported in Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org. Four control groups were used in this study: (1) patients without MCAD convalescing from mild to moderate (n = 17) and (2) severe (n = 15) forms of COVID-19 and who had already been evaluated with SARS-CoV-2 ELISpot and serology assays in Necker Hospital’s immunology laboratory, (3) patients with idiopathic MCAS with or without a history of COVID-19, and (4) patients without MCAD with no history of COVID-19 (n = 15). We compared the patients with cMCAD with age-matched patients with MCAS who presented symptoms of MC activation and were being treated with antimediator agents; at the time of the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the immunoassays, all the 11 patients with MCAS were being treated with H1 antihistamines, 8 were being treated with H2 antihistamines, and 5 were being treated with montelukast. The cMCAD and MCAS patient subgroups did not differ significantly with regard to age (mean age, 45.6 vs 49.2 years, respectively; P = .35).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, Calif). Groups were compared using Student t test, a χ2 test, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Data were expressed as the mean, median (interquartile range), or median (range). The threshold for statistical significance was set to P less than .05 (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, in figure legends).

Results

From February 1, 2020, to February 1, 2021, 32 patients with cMCADs and proven COVID-19 were prospectively identified by the CEREMAST network (Figure 1). Eighteen of the 32 had replied to the questionnaire, and 14 patients had been subsequently identified by referring physicians in CEREMAST centers. No additional inpatient cases were found in the Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris (Paris Public Hospital Group) database.

The characteristics and outcomes of the 32 patients with cMCADs and COVID-19 are summarized in Table I . The median (range) age was 49.7 years (range, 25.6-76.4 years), with female predominance (59.4%). The cMCAD subtype was cutaneous mastocytosis or mastocytosis in the skin in 14 patients, ISM in 15 patients, smoldering systemic mastocytosis in 1 patient, and MMAS in 2 patients. Of the 21 patients having undergone genetic testing, 18 (85.7%) carried the D816V KIT mutation. Ten patients (31.3%) had experienced a severe anaphylactic reaction, and the median (range) basal serum tryptase level before the appearance of clinical or laboratory signs of COVID-19 was 13.0 μg/L (2.7-163.0 μg/L). Risk factors for severe COVID-19 were present in 13 of the 32 patients (40.6%), and 4 had at least 2 risk factors18: a body mass index more than 30 (n = 4), age more than 65 years (n = 4), ongoing cytoreductive therapy (midostaurin or cladribine) or recent (in the previous 12 months) administration of cladribine (n = 3), cardiovascular conditions (including arterial hypertension and chronic heart failure) (n = 7), and diabetes (n = 2). At the time of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, 23 of the 32 patients (71.9%) were taking symptomatic medications (H1 antihistamines, H2 antihistamines, and/or montelukast), 1 patient with smoldering systemic mastocytosis was receiving midostaurin after failure to respond to cladribine, and 1 patient with ISM had recently received cladribine.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with cMCADs and COVID-19 and their outcomes

| No. | Sex | Age (y) | BMI | cMCADs | KIT mutation | History of severe anaphylaxis | Risk factors | Tryptase (μg/L) | Treatment: Anti-H1 | Treatment: Anti-H2 | Treatment: Montelukast | Cytoreductive therapy | COVID-19 scale | cMCAD symptoms during COVID-19 | Fever during COVID-19 | Anosmia/ ageusia during COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2 PCR test | SARS-CoV-2 serology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 25.6 | 17.4 | ISM | WT | No | No | 3.9 | No | Yes | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 2 | F | 26.7 | 24.3 | CM | D816V | No | No | 4.4 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | More severe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Negative |

| 3 | F | 29.9 | 23.9 | MIS | NA | No | No | 4.7 | No | No | No | No | 2 | No change | No | No | No | Positive |

| 4 | F | 33.4 | 28.1 | CM | D816V | Yes | No | 6.6 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | No | Positive |

| 5 | F | 35.5 | 33.1 | MIS | NA | No | Yes | 7.4 | No | No | No | No | 2 | No change | No | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 6 | F | 38.3 | 18.4 | ISM | D816V | Yes | No | 7.0 | No | No | No | No | 2 | More severe | No | No | Yes | Negative |

| 7 | F | 40.3 | 21.0 | CM | WT | No | No | 8.1 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | No | Yes | No | Positive |

| 8 | F | 41.4 | 22.5 | ISM | NA | No | No | 7.7 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | Less severe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 9 | F | 42.3 | 20.0 | MMAS | D816V | Yes | No | 18.5 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | More severe | No | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 10 | M | 42.4 | 33.5 | ISM | D816V | No | Yes | 2.7 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | Less severe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 11 | F | 43.3 | 25.0 | CM | WT | Yes | No | 13.0 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | No change | Yes | No | Yes | Positive |

| 12 | F | 43.3 | 24.3 | ISM | D816V | Yes | Yes | 60.0 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | More severe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 13 | F | 43.8 | 25.1 | MIS | NA | No | No | 13.0 | No | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 14 | M | 45.3 | 30.8 | MMAS | D816V | Yes | Yes | 45.0 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | No | No | Positive |

| 15 | F | 48.1 | 17.6 | ISM | D816V | Yes | No | 99.8 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | No change | No | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 16 | M | 49.1 | 27.4 | ISM | D816V | No | No | 14.8 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 | More severe | Yes | Yes | No | Positive |

| 17 | M | 50.3 | 23.2 | MIS | NA | No | No | 18.6 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | No | No | Yes | Positive |

| 18 | M | 51.7 | 26.4 | ISM | D816V | No | No | 42.8 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 19 | F | 52.2 | 19.5 | ISM | NA | No | No | 7.9 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | No change | Yes | No | No | Positive |

| 20 | F | 52.4 | 30.1 | CM | D816V | No | Yes | 37.2 | Yes | No | No | No | 5∗ | More severe | Yes | No | Yes | Positive |

| 21 | F | 52.9 | 17.5 | ISM | D816V | No | Yes | 38.6 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Negative |

| 22 | F | 53.1 | 27.0 | MIS | NA | No | No | 31.4 | No | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 23 | M | 56.0 | 26.8 | ISM | NA | No | Yes | 19.0 | No | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | No | Positive |

| 24 | F | 59.6 | 21.6 | MIS | NA | No | No | 56.0 | No | No | No | No | 2 | More severe | No | No | Yes | Positive |

| 25 | M | 60.7 | 26.6 | CM | D816V | No | No | 12.0 | No | No | No | No | 1 | No change | No | No | Yes | Positive |

| 26 | M | 62.2 | 26.5 | ISM | D816V | No | Yes | 6.1 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | No | No | Positive |

| 27 | M | 62.2 | 24.2 | CM | D816V | No | No | 18.6 | Yes | No | No | No | 2 | No change | Yes | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 28 | M | 63.2 | 28.1 | MIS | NA | Yes | Yes | 11.2 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | No change | No | Yes | Yes | Positive |

| 29 | M | 65.6 | 26.7 | ISM | D816V | Yes | Yes | 27.8 | No | No | No | No | 5∗ | No change | Yes | No | Yes | Positive |

| 30 | F | 73.9 | 21.2 | SSM | D816V | No | Yes | 163.0 | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | No change | Yes | No | No | Positive |

| 31 | M | 76.2 | 25.4 | ISM | D816V | Yes | Yes | 8.5 | Yes | No | No | No | 3 | Less severe | Yes | No | Yes | Positive |

| 32 | M | 76.5 | 27.8 | ISM | NA | No | Yes | 7.6 | No | Yes | No | No | 2 | More severe | Yes | No | Yes | Positive |

BMI, Body mass index; CM, cutaneous mastocytosis; F, female; M, male; MIS, mastocytosis in the skin; NA, not available; SSM, smoldering systemic mastocytosis; WHO, World Health Organization.

Risk factors: risk factors for severe COVID-19.18 Cytoreductive therapy: midostaurin or ongoing/recent (previous 12 mo) administration of cladribine. COVID-19 scale: WHO COVID-19 clinical progression scale.19

Patients are listed in order of increasing age (y).

Patients treated with corticosteroids.

With regard to the diagnosis of COVID-19, 23 of the 32 patients (71.9%) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result on a nasal swab and 9 of the 32 had a negative PCR test result (or did not undergo a PCR test on a nasal swab, due to nonavailability of the procedure at the time of infection) and positive serology test result. The great majority of the patients (29 of 32) became seropositive during their follow-up. As expected, patients with subsequently available serum samples (n = 4) became seronegative after a median follow-up of 33 weeks. Regarding the symptoms of COVID-19, 22 of the 32 (68.8%) patients had fever (>38°C) and 18 (56.3%) had anosmia and/or ageusia. Only 2 patients were admitted to hospital for corticosteroid therapy and oxygen therapy (corresponding to stage 5 on the World Health Organization COVID-19 clinical progression scale19) but neither required noninvasive or mechanical ventilation. Interestingly, 8 of the 32 patients (25.0%) reported an increase in signs of MC activation during the episode of COVID-19, whereas 3 (9.4%) reported a decrease. No recurrences of the infection were reported.

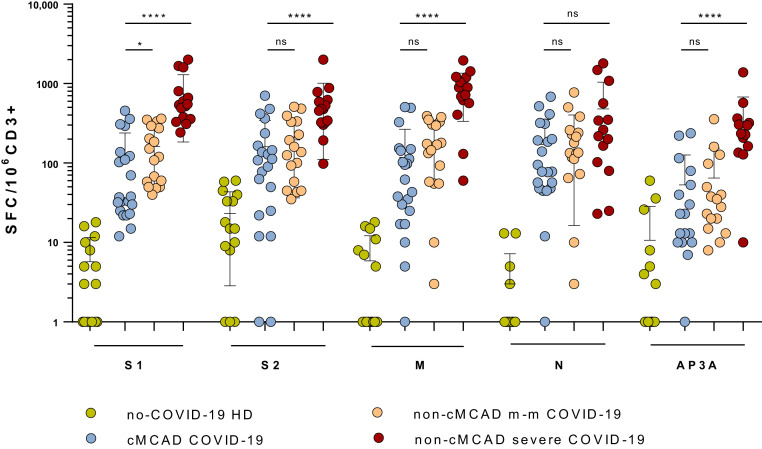

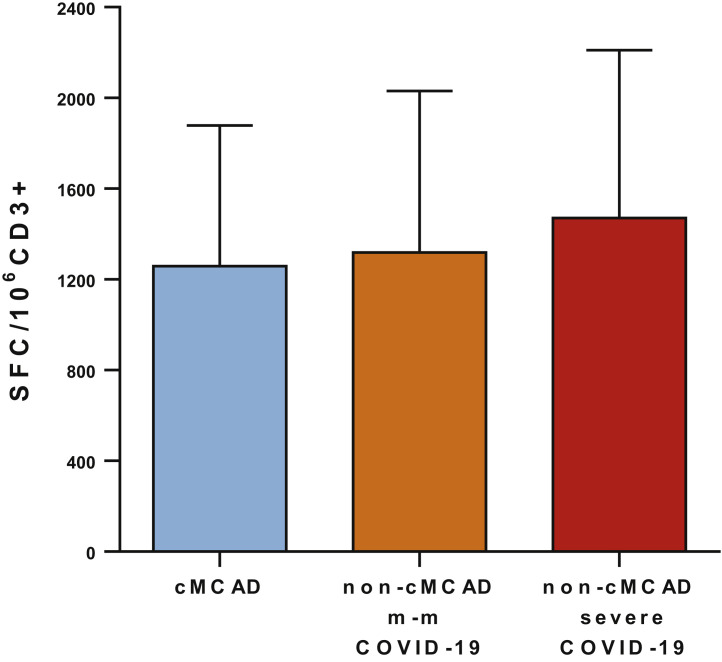

The specific cellular and humoral anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune responses were studied in 21 patients with cMCADs a median (interquartile range [IQR]) of 24 weeks (7-36) from infection. Overall, 20 of the 21 patients with cMCAD developed a specific T-cell response against at least 1 of the SARS-CoV-2 peptide pools tested. The responses were usually moderately intense. The median (IQR) intensity was 37 (24-130) SFC/103 CD3 for the S1 pool, 108 (23-201) SFC/103 CD3 for the S2 pool, 62 (21-146) SFC/103 CD3 for the M pool, 78 (48-256) SFC/103 CD3 for the N pool, and 23 (10-66) SFC/103 CD3 for the AP3a pool. The only patient (no. 6) who did not develop a specific T-cell response was young (38 years), had presented mild symptoms of COVID-19 (confirmed by a positive PCR test result on a nasal swab), and did not have a history of immunodeficiency or immunosuppressive therapy.

Interestingly, the frequencies and intensities of the S2, M, N, and AP3a pool responses observed for patients with cMCAD were similar to those observed for the control group of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 (n = 17) (Figure 2 ). However, the median (IQR) response for the spike glycoprotein N-terminal fragment pool was significantly lower for the patients with cMCADs (37 [24-130] SFC/103 CD3) than for the controls with mild to moderate COVID-19 (114 [52-289] SFC/103 CD3; P = .0288). The SARS-CoV-2–specific T-cell responses were significantly lower for patients with cMCAD (P < .001) than for controls with severe COVID-19 (n = 15), with the exception of the N pool (Figure 2). It is noteworthy that we did not detect (or detected very few) specific T-cell responses to the SARS-CoV-2 envelope small membrane protein in any of the groups. The anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune profiles of patient number 20 (grade 5 on the World Health Organization COVID-19 clinical progression scale) and patient number 30 (who had recently been given cladribine) did not appear to differ from those observed in the other patients.

Figure 2.

Quantification of specific anti–SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses, using an ELISpot assay. The tested SARS-CoV-2 peptide pools were derived from a peptide scan through the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (S1: N-terminal fragment, S2: C-terminal fragment), membrane protein (M), nucleoprotein (N), and ORF3a protein (AP3a). The negative controls were PBMCs in culture medium alone, and the positive controls were PHA and the CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool. Results were expressed as the number of SFCs/106 CD3+ T cells after subtraction of the background values from wells with nonstimulated cells. All differences between the non–COVID-19 and COVID-19 groups were statistically significant (P < .001). cMCADs, Convalescent patients with cMACDs; HD, healthy donors; non-cMCAD m-m COVID-19, control patients without cMACD convalescing from a mild to moderate form of COVID-19 (n = 17); non-cMCAD non-COVID-19, non-cMCAD, non-COVID-19 controls (n = 15); non-cMCADs severe COVID-19, control patients without cMACD convalescing from a severe form of COVID-19 (n = 15). ns, nonsignificant. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

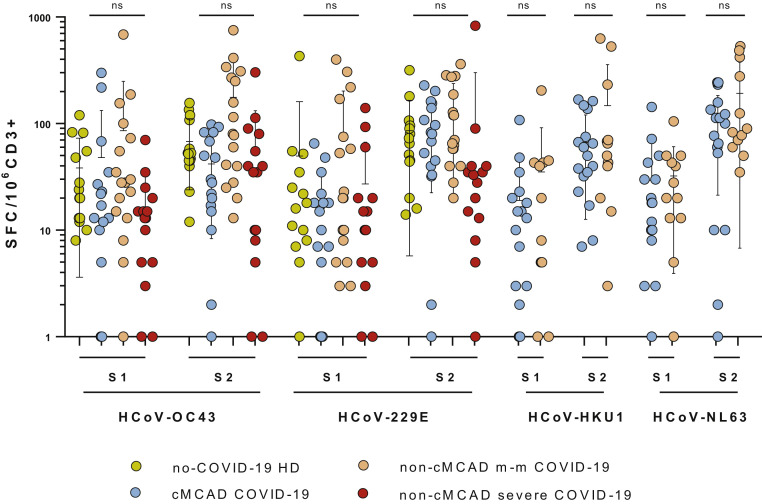

To evaluate the overall anticoronavirus immune response in 18 patients with cMCADs, we studied T-cell–specific responses against the spike glycoprotein of human alpha- and beta-coronaviruses HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1. Two peptide pools (S1 and S2) were tested, as had been done for the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (see Figure E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). The samples from patients with cMCAD and controls without cMCAD gave very similar responses. We did not evidence any defects in the antiendemic coronavirus response in patients with cMCADs; the frequencies and intensities were similar to those observed for controls without cMCAD. The same was true when comparing IFN-γ production responses to the ELISpot positive control CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool (containing 176 known peptide epitopes derived from a broad range of infectious agents) in patients with cMCAD versus patients without cMCAD (see Figure E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

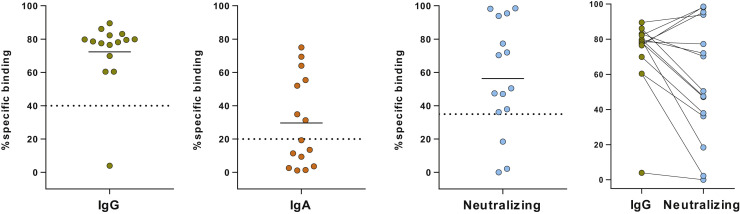

In parallel with the ELISpot assay, we also used a high-sensitivity assay (the S-flow assay) to study SARS-CoV-2–specific IgG and IgA in 15 patients with cMCAD. Fourteen of the 15 patients were positive for IgG, and 7 of the 15 were positive for IgA. The IgG-negative patient (no. 6) had a negative ELISpot assay. Furthermore, we used a viral pseudoparticle neutralization assay to determine whether the SARS-CoV-2–specific IgGs were neutralizing. We detected neutralizing antibodies in 12 of the 14 IgG-seropositive patients (86%) and found that anti–SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity (the IgG titer) was associated with a high level of neutralizing antibody (see Figure E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

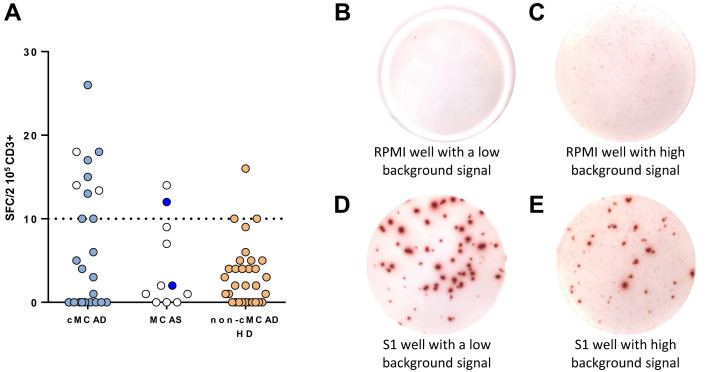

Interestingly, inspection of the ELISpot plates showed that the background signal was significantly higher in cMCAD wells than in non-cMCAD control wells. In wells containing nonstimulated PBMCs in culture medium but with no peptide pools, we counted more than 10 small spots per 2 × 105 CD3+ cells in 10 of the 24 patients with cMCAD (with or without a history of COVID-19), 3 of the 31 controls without cMCAD (P = .009 in Fisher exact test), and 2 of the 11 controls with idiopathic MCAS (Figure 3 , A).

Figure 3.

Spontaneous IFN-γ production by PBMCs from patients, as measured in an ELISpot assay. (A) Graphic representation of the ELISpot assays. cMCADs, patients with cMCADs; non-cMCAD control groups: MCAS, patients with idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome; CTR: non-cMCAD/non-MCAS control patients convalescing from COVID-19 (n = 32); HD, healthy donors. Empty circles: no history of COVID-19. Filled circles: history of COVID-19. Pictures of ELISpot assays. (B) A well with nonstimulated PBMCs from a COVID-19 non-cMCAD control. (C) A well with nonstimulated PBMCs from a patient with COVID-19 and cMCAD. (D) A well with PBMCs from a COVID-19 non-cMCAD control after stimulation for 18 to 20 hours with individual 15-mer 11-aa overlapping peptide pools derived from the SARS-CoV-2 N-terminal fragment spike protein. (E) A well with PBMCs from a patient with COVID-19 and cMCAD after stimulation with individual 15-mer 11-aa overlapping peptide pools derived from the SARS-CoV-2 N-terminal fragment spike protein.

It should be noted that the SARS-CoV-2–specific spots were much larger and more intense than the background spots (Figure 3, B-E). Thus, adjustment to the ELISpot reader’s settings made it possible to count the SARS-CoV-2–specific spots accurately and objectively. This phenomenon resulted from spontaneous IFN-γ release in the absence of stimulation. Given that we had tested the total PBMC fraction, we were not able to identify the specific subset of IFN-γ–producing cells. PBMCs include T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, and other myeloid cells (such as dendritic cells). Spontaneous IFN-γ release can be associated with elevated levels of basal T-cell activation. In a study of HIV-1–seronegative people, Liu et al20 reported that the frequency of activated CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD38+HLA-DR+) and CD8+ T cells (CD8+CD38+HLA-DR+) was greater in individuals with a high background than in individuals with a low background. Another hypothesis involves NK cells, which might contribute to the maintenance of an elevated baseline IFN-γ level. It has been reported that NK cells from polyallergic patients spontaneously released greater amounts of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 than NK cells from healthy individuals did,21 highlighting the in vivo activation of NK cells in atopic patients and suggesting that NK cells might be involved in an unbalanced cytokine network in allergic inflammation.

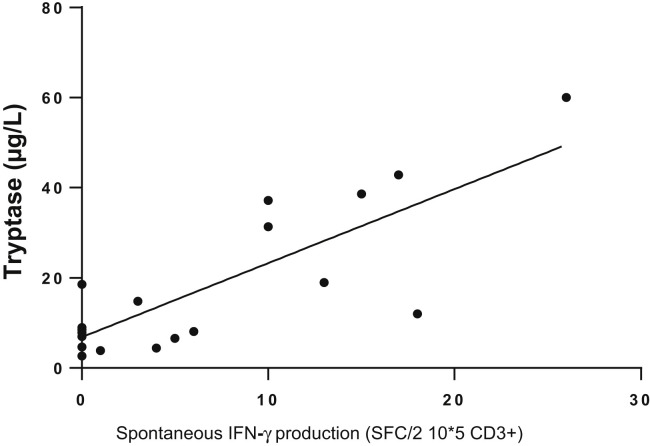

Accordingly, we sought to determine whether the spontaneous release of IFN-γ by PBMCs from patients with cMCAD was related to NK-cell activity, as has been reported for polyallergic patients. Human NK cells can be divided into NK1 and NK2 subsets on the basis of their ability to secrete IFN-γ.22 NK1 secretes IFN-γ and inhibits IgE synthesis in allergy.21 Levels of total IgE might therefore constitute an indirect marker of NK1 activation. Thus, we determined the total IgE titer in sera from 17 patients with cMCADs. The cohort’s total IgE levels were generally low (median [IQR], 20 IU/mL [12.8-36.5]), and were not correlated with spontaneous IFN-γ release. Lastly, we sought to determine whether the spontaneous IFN-γ release was correlated with the patients’ characteristics. Although there was no correlation between spontaneous IFN-γ release and age, current symptomatic medications, a history of anaphylaxis, or the presence of the KIT D816V mutation, the basal serum tryptase level was indeed correlated in patients with cutaneous mastocytosis, mastocytosis in the skin, or ISM (Figure 4 ; r 2 = 0.61; P = .0004).

Figure 4.

Correlation between basal tryptase level (μg/L) and spontaneous IFN-γ production (SFCs/2 × 105 CD3), as observed in ELISpot assays. n = 24 patients with CM, MIS, and ISM. Linear regression: r2 = 0.44 (P < .0004). CM, Cutaneous mastocytosis; MIS, mastocytosis in the skin.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to have investigated the antiviral immune response in patients with cMCADs. Given that MCs are key players in the TH2 immune response, one could reasonably fear that patients with cMCADs might produce abnormally poor immune responses to infections by viruses such as SARS-CoV-2. To address this hypothesis, we studied a comprehensive range of responses and outcomes in patients with cMCAD having developed PCR- or serology-confirmed COVID-19 during a 12-month period in France. Overall, no cases of severe COVID-19 were observed in this comprehensive series of patients despite the high prevalence of risk factors (obesity, advanced age, cardiovascular conditions, immunosuppressive treatments, etc). Strikingly, only 2 patients (with 1 and 3 risk factors, respectively) had to be hospitalized for low-flow oxygen therapy, and the outcomes were favorable in both cases. These findings are in line with recently published data from an international study.23 However, the present study extends our knowledge of cMCADs and COVID-19 because of the exhaustive nature of our inclusion process for patients with cMCADs through the nationwide CEREMAST rare disease network. Indeed, whenever a patient with mastocytosis not referenced in the CEREMAST network was hospitalized for the treatment of COVID-19 in an intensive care unit, the local and national reference centers were systematically contacted for an expert opinion on potential drug contraindications (due to the mandatory precautions needed for anesthesia). The exhaustive recruitment of patients with cMCADs and severe or life-threatening COVID-19 was confirmed by consulting Programme de médicalisation des systèmes d'information hospital discharge records for the greater Paris region; we did not retrieve any inpatients who had not been detected through the CEREMAST network. For obvious reasons, the only source of study bias was related to patients with asymptomatic, mild, or moderate forms of COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization nor request advice from their referring physicians.

To characterize the antiviral immune responses in patients with cMCADs, we have investigated, using ELISpot assay, the T-cell–specific responses against SARS-CoV-2, endemic coronavirus, and the CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool containing 176 known peptide epitopes derived from a broad range infectious agent. Furthermore, we studied the specific humoral anti–SARS-CoV-2 response by assaying circulating levels of specific IgG and IgA antibodies and neutralizing antibodies.

We observed that patients with cMCADs and controls without cMCAD with a history of mild or moderate COVID-19 had very similar T-cell profiles in response to SARS-CoV-2, endemic coronaviruses, and the CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool. Considering these observations as a whole and in contrast to initial expectations, we believe that patients with mastocytosis were indeed able to develop an effective, protective TH1-cell response against SARS-CoV-2. Thus, MCs from patients with cMCADs do not appear to worsen the TH1 response. However, given that less intense responses against SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein were observed in patients with cMCAD, we cannot rule out an impact of MCs on the amplitude of the TH1 response; this would raise concerns about the postimmunization cellular response. Furthermore, recent research has shown that MCs are involved in the TH1 response in general and the TH1 response to viruses in particular.24, 25, 26 MCs might have a role in the TH1/TH2 balance that is potentially important for preventing the development of severe forms of COVID-19.

Unexpectedly, our ELISpot assay results revealed that spontaneous IFN-γ release from PBMCs (ie, release in the absence of any stimulation) was more frequent in patients with cMCAD than in controls. We found that spontaneous IFN-γ release was positively correlated with the basal tryptase levels of patients with cMCAD; this was the only correlated clinical and laboratory characteristic, in fact. Although tryptase is very unlikely to be directly involved in this phenotype (especially since patients with advanced mastocytosis have very high tryptase levels and are not known to be especially protected against infection), we believe that the clonal MC burden is linked to IFN-γ release in patients with nonadvanced mastocytosis. To our knowledge, this finding has not previously been reported in the literature and may suggest a degree of additional protection against severe viral diseases. Our laboratory is now working to determine whether this observation is related to either a specific cytokine profile in a patient’s plasma or a direct cellular interaction between MCs and T cells. If confirmed, this specific phenotype in patients with cMCAD might lead to therapeutic implications in the field of infectious diseases.

Overall, our results showed that patients with cMCADs were able to develop effective, protective cellular and humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2. However, all 4 of the evaluable patients with serial serology data had become seronegative after a median of 33 weeks. Thus, anti–SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is strongly recommended in this specific patient population, although its level of effectiveness remains to be characterized.

Conclusions

Non-advanced mastocytosis and MMAS appear not to confer an elevated risk of severe COVID-19 on patients. This finding might be due to the spontaneous IFN-γ production observed in patients with cMCADs but must be confirmed by further clinical and laboratory studies. If confirmed, this specific immune profile might explain the observed protection against severe COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients who filled out the questionnaire and the health care professional who cared for the patients with COVID-19. The authors would like to thank Fondation Université de Paris, AXA research fund, Fondation Hôpitaux de Paris-Hôpitaux de France, Mécénat du GH APHP. CUP, Fondation pour la Recherche en Physiologie and DMU BioPhyGen for the funding of the COVID-HOP study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: J. Rossignol received consulting fees from Blueprint and Novartis. C. Gaudy received consulting fees and/or honoraria from BMS, Blueprint, MSD, and Roche. G. Damaj received consulting fees and/or honoraria from Takeda, Iqone, and Blueprint. M. Hamidou received consulting fees from Blueprint. L. Bouillet received research grants, and/or consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Takeda, CSL Behring, Biocryst, Biomarin, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline. C. Lavigne received consulting fees and/or honoraria from Sanofi-Genzyme, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Shire, Ultragenyx, and Biomarin. O. Tournilhac is investigator for Amgen, Gilead, Takeda, Janssen, Morphosys, Celgene, Roche, Genetech, Abbvie sponsored trials, consultant (advisory boards) for Roche, Janssen, Gilead, Takeda and Abbvie and received research grants from de Roche, Gilead, Amgen, Chugaï, Novartis. M. Arock received consultancy fees from Blueprint et Novartis. O. Hermine reports consultancy, equity ownership, honoraria, and research funding from AB Science and research funding from Celgene and Novartis. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository

Figure E1.

T-cell responses to common coronaviruses in patients with cMCAD (n = 17), and patients without cMCAD with a history of mild to moderate COVID-19 (n = 17) or severe COVID-19 (n = 15), or healthy donors (n = 15). Identification of HCoV-OC43–, HCoV-229E–, HCoV-HKU1–, and HCoV-NL63–specific T-cell responses, using ELISpot assays. Results were expressed as SFCs/106 CD3+ T cells after subtraction of background values from wells containing nonstimulated cells. cMCADs, Patients with cMCADs, convalescing from mild to moderate (m-m) or severe COVID-19; ns, nonsignificant

Figure E2.

T-cell responses to the CEFX Ultra SuperStim Pool. cMCADs, Patients with MCADs, convalescing from mild to moderate (m-m) or severe COVID-19.

Figure E3.

Two left-most panels: serologic status for anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG antibodies, determined in an S-flow assay. The dashed line indicates the positivity threshold. Third panel: Percentage IgG neutralizing ability, determined in a viral pseudoparticle assay. Fourth panel: relationship between the IgG titer and the neutralizing activity.

Table E1.

Numbers and characteristics of patients with cMCAD and controls studied, by assay

| Characteristic | cMCADs: Whole cohort | cMCADs: SARS-CoV-2 ELISpot assay | cMCADs: Common coronavirus ELISpot assay | cMCADs: Humoral assay | Non-cMCADs: ELISpot assay | MCAS: ELISpot assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 32 | 22 | 18 | 15 | 32 | 11 |

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 50 (42-60) | 51 (41-55) | 51 (41-56) | 52 (41-54) | 52 (41-62) | 40 (35-58) |

| Female/male sex ratio | 19/13 | 13/9 | 9/9 | 8/7 | 16/16 | 10/1 |

References

- 1.Valent P., Akin C., Metcalfe D.D. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood. 2017;129:1420–1428. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-731893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim K., Tefferi A., Lasho T.L., Finke C., Patnaik M., Butterfield J.H., et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113:5727–5736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotlib J., Pardanani A., Akin C., Reiter A., George T., Hermine O., et al. International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) & European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) consensus response criteria in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013;121:2393–2401. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-458521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helmy Y.A., Fawzy M., Elaswad A., Sobieh A., Kenney S.P., Shehata A.A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1225. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadjadj J., Yatim N., Barnabei L., Corneau A., Boussier J., Smith N., et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastard P., Rosen L.B., Zhang Q., Michailidis E., Hoffmann H.-H., Zhang Y., et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z., John Wherry E. T cell responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:529–536. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., Mateus J., Dan J.M., Moderbacher C.R., et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. 1489-501.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Ploeg E.K., Hermans M.A.W., van der Velden V.H.J., Dik W.A., van Daele P.L.A., Stadhouders R. Increased group 2 innate lymphoid cells in peripheral blood of adults with mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.037. 1490-6.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzoni A., Siraganian R.P., Leifer C.A., Segal D.M. Dendritic cell modulation by mast cells controls the Th1/Th2 balance in responding T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:3577–3581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulfone-Paus S., Bahri R. Mast cells as regulators of T cell responses. Front Immunol. 2015;6:6–11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith N., Pietrancosta N., Davidson S., Dutrieux J., Chauveau L., Cutolo P., et al. Natural amines inhibit activation of human plasmacytoid dendritic cells through CXCR4 engagement. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14253. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y., Jin Y., Han D., Zhang G., Cao S., Xie J., et al. Mast cell-induced lung injury in mice infected with H5N1 influenza virus. J Virol. 2012;86:3347–3356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kritas S.K., Ronconi G., Caraffa A., Gallenga C.E., Ross R., Conti P. Mast cells contribute to coronavirus-induced inflammation: new anti-inflammatory strategy. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34:9–14. doi: 10.23812/20-Editorial-Kritas. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valent P., Akin C., Bonadonna P., Hartmann K., Brockow K., Niedoszytko M., et al. Proposed diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected mast cell activation syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.01.006. 1125-11233.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gülen T., Akin C., Bonadonna P., Siebenhaar F., Broesby-Olsen S., Brockow K., et al. Selecting the right criteria and proper classification to diagnose mast cell activation syndromes: a critical review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:3918–3928. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grzelak L., Temmam S., Planchais C., Demeret C., Tondeur L., Huon C., et al. A comparison of four serological assays for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human serum samples from different populations. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., Bacon S., Bates C., Morton C.E., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e192–e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu A.Y., De Rosa S.C., Guthrie B.L., Choi R.Y., Kerubo-Bosire R., Richardson B.A., et al. High background in ELISpot assays is associated with elevated levels of immune activation in HIV-1-seronegative individuals in Nairobi. Immunity Inflamm Dis. 2018;6:392–401. doi: 10.1002/iid3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aktas E., Akdis M., Bilgic S., Disch R., Falk C.S., Blaser K., et al. Different natural killer (NK) receptor expression and immunoglobulin E (IgE) regulation by NK1 and NK2 cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deniz G., Akdis M., Aktas E., Blaser K., Akdis C.A. Human NK1 and NK2 subsets determined by purification of IFN-gamma-secreting and IFN-gamma-nonsecreting NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:879–884. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<879::AID-IMMU879>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannetti M.P., Weller E., Alvarez-Twose I., Torrado I., Bonadonna P., Zanotti R., et al. COVID-19 infection in patients with mast cell disorders including mastocytosis does not impact mast cell activation symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2083–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAlpine S.M., Issekutz T.B., Marshall J.S. Virus stimulation of human mast cells results in the recruitment of CD56+ T cells by a mechanism dependent on CCR5 ligands. FASEB J. 2012;26:1280–1289. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-188979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebert S., Becker M., Lemmermann N.A.W., Büttner J.K., Michel A., Taube C., et al. Mast cells expedite control of pulmonary murine cytomegalovirus infection by enhancing the recruitment of protective CD8 T cells to the lungs. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker M., Lemmermann N.A., Ebert S., Baars P., Renzaho A., Podlech J., et al. Mast cells as rapid innate sensors of cytomegalovirus by TLR3/TRIF signaling-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:192–201. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]