Abstract

We report on a 38-day-old infant who developed pleuropneumonia due to a Staphylococcus aureus strain responsible for familial furunculosis, which was acquired by maternal breast-feeding. All isolates from the infant and parents were genetically related by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis and produced Panton-Valentine leukocidin.

Staphylococcal pleuropneumonia in infants and children is a public health problem in developing countries but has become rare in industrialized countries. Severe respiratory disease in immunocompetent children and chronic furunculosis have been associated with Staphylococcus aureus strains that produce Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a cytotoxin that causes leukocyte destruction and tissue necrosis (4, 8).

Case report.

We report on a 38-day-old infant who developed pleuropneumonia due to a PVL-producing S. aureus strain responsible for familial furunculosis, which was acquired by maternal breast-feeding. This breast-fed infant, born at 40 weeks of gestation, was admitted to the neonatal unit of Robert Debré Hospital with septic shock. She had developed retroseptal periobital cellulitis following conjunctivitis and ethmoiditis diagnosed by contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography of the orbit.

She was leukopenic (leukocyte count, 2,500/mm3; 87% neutrophils) and febrile (temperature, 39°C) and had a marked inflammatory syndrome (C-reactive protein level, 361 mg/liter; fibrinogen level, 6.7 g/liter). Antimicrobial therapy was started with cefotaxime (100 mg/kg of body weight/day) plus fosfomycin (200 mg/kg/day). Eye pus (sample S1), a sample from a cheek wound (sample S2), and, subsequently, a sample for blood culture (sample S3) yielded S. aureus. The mother's breast milk (sample S4), sampled after local disinfection, also yielded S. aureus. On day 3 after onset, the initial antimicrobial regimen was replaced by oxacillin (200 mg/kg/day) and gentamicin (5 mg/kg/day) plus rifampin (20 mg/kg/day) on the basis of susceptibility testing and in vitro time-kill curve studies. The infant subsequently developed respiratory failure and was admitted to the intensive care unit for bilateral staphylococcal pneumonia. On days 5 and 6 of illness, two samples for blood cultures (samples S5 and S6) were positive for S. aureus. Blood cultures became sterile 4 days after the beginning of second-line treatment. The chest X-ray film showed infiltrates, pneumothorax, and pleural extravasation, which required chest tube drainage. Samples of the draining pleural fluid were sterile. Respiratory function improved very slowly, and the production of compressive bubbles on the mediastinum led, 5 months later, to partial resection of the lower right lobe.

Surveillance cultures were performed because of the chronic furunculosis in both parents. Samples from the father's nostrils (sample S7) and throat (sample S8) and the mother's groin (sample S9) yielded S. aureus.

Identification of S. aureus was based on colony morphology, coagulation of citrated rabbit plasma (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), and production of a clumping factor (Staphyslide test; bioMérieux).

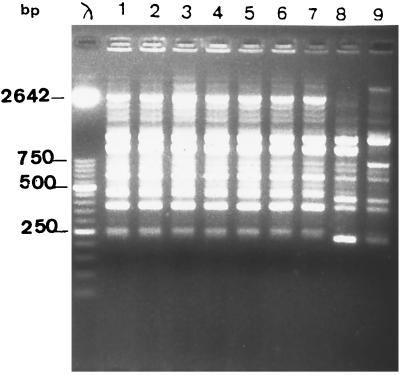

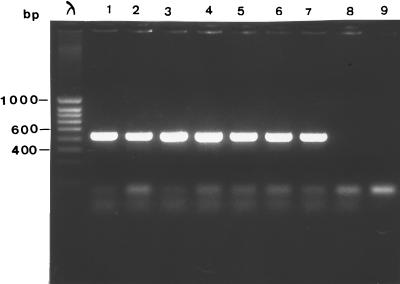

A total of seven isolates from the neonate (isolates from samples S1, S2, S3) and the parents (isolates from samples S4, S7, S8, and S9) were genotyped and analyzed for PVL production. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis with two primers (primer A3 [5′-AGTCAGCCAC-3′] and primer 217Δ2 [5′-GCCCCCAGGGGCACAGT-3′]) was used for genotyping, as described previously (1). Unrelated isolates of S. aureus obtained from two patients hospitalized in two different wards of our hospital were studied for comparison. The seven isolates from the infant and parents were genetically related to each other and were unrelated to the control strains (Fig. 1), confirming both the origin of the septicemia in the infant and the intrafamilial transmission. PVL production was characterized by using a previously described PCR method (8). As expected, a fragment of 433 bp was obtained with the seven isolates (Fig. 2). PVL production was confirmed by immunoprecipitation assay (H. Monteil, Institut de Bactériologie de la Faculté de Médecine, Strasbourg, France).

FIG. 1.

DNA fingerprinting of S. aureus by RAPD analysis with primer A3 (5′-AGTCAGCCAC-3′) Lane λ, bacteriophage λ molecular size marker; lanes 1 to 7, isolates from samples S1, S2, S3, S4, S7, S8, and S9, respectively; lanes 8 and 9, unrelated isolates.

FIG. 2.

PCR detection of the PVL gene. Lane λ, bacteriophage λ molecular size marker; lanes 1 to 7, isolates from samples S1, S2, S3, S4, S7, S8, and S9, respectively; lanes 8 and 9, negative controls.

Discussion.

The incidence of orbital infection secondary to ethmoiditis in children increases with age and is rare before age 1 year (10). We describe a 38-day-old infant who developed pleuropneumonia preceded by periorbital infection with a PVL-producing strain of S. aureus that was transmitted by maternal breast-feeding.

Leukocidin is a two-component toxin which targets polymorphonuclear cells, monocytes, and macrophages (11). Its toxicity involves two unlinked exoproteins (class S and class F components) which lead to transmembrane pore formation and ultimately to cell death. PVL induces a process of necrosis by stimulating granulocyte synthesis of inflammatory mediators. PVL also participates in the extension of the infection by inhibiting phagocyte functions and provoking destruction of these granulocytes (7). This may have been responsible for the marked leukopenia in our patient.

PVL production can lead to secondary organ involvement, especially of the lungs. In this infant the initial infection (of the ethmoid sinus) may thus have been propagated via septic metastasis to the lungs, leading to pleuropneumonia with marked necrosis of the pulmonary parenchyma and major functional sequelae. PVL has been found in 85% of S. aureus strains isolated from patients with community-acquired pneumonia (8). Pneumonia due to PVL-producing S. aureus has been associated with septicemia (3). Early appropriate antibiotic treatment is thus crucial (2). Blood cultures became sterile only after 4 days of a second-line antibiotic regimen (oxacillin and rifampin plus gentamicin). Similar late responses to treatment have been described previously (3) and have been linked to the number and size of pulmonary abscesses, which hinder eradication of the pathogen. PVL has been found in 86% (9) and 93% (8) of S. aureus strains isolated from furuncles. Both of the infant's parents had chronic furunculosis. In the patient presented here, familial carriage of the strain was probably responsible for transmission to the infant during breast-feeding. Familial carriage of S. aureus has been shown to be a risk factor for subsequent infection with the same organism in neonates (6). Recurrent furunculosis and small familial outbreaks of furuncles are difficult to treat (5). Strict hygiene measures and decolonization of parents with chronic furunculosis due to PVL-producing S. aureus strains, and particularly breast-feeding mothers, might reduce the risk of transmission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bingen E, Bonacorsi S, Rohrlich P, Duval M, Lhopital S, Brahimi N, Vilmer E, Goering R V. Molecular epidemiology provides evidence of genotypic heterogeneity of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O: 12 outbreak isolates from a pediatric hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3226–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3226-3229.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buwalda M, Speelberg B. Metastatic staphylococcal lung abscess due to a cutaneous furuncle. Neth J Med. 1995;47:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0300-2977(95)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couppié P, Hommel D, Prévost G, Godart M C, Moreau B, Sainte Marie D, Peneau C, Hulin A, Monteil H, Pradinaud R. Septicémie àStaphylococcus aureus producteurs de leucocidine de Panton-Valentine 3 observations. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1997;124:684–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cribier B, Prevost G, Couppié P, Finck-Barbançon V, Grosshans E, Piemont Y. Staphylococcus aureus leukocidin: a new virulence factor in cutaneous infections? An epidemiological and experimental study. Dermatology. 1992;185:175–185. doi: 10.1159/000247443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedstrom S A. Recurrent furonculosis. Bacteriological findings and epidemiology in 100 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1981;13:115–119. doi: 10.3109/inf.1981.13.issue-2.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollis R J, Barr J L, Doebbeling B N, Pfaller M A, Wenzel R P. Familial carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and subsequent infection in a premature neonate. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:328–332. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konig B, Prevost G, Piemont Y, Konig W. Effects of Staphylococcus aureus leukocidins on inflammatory mediator release from human granulocytes. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:607–613. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter M O, Gauduchon V, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prevost G, Couppié P, Prevost P, Gayet S, Petiau P, Cribier B. Epidemiological data on Staphylococcus aureus strains producing synergohymenotropic toxins. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:237–245. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-4-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders M W, Jones N S. Periorbital abscess due to ethmoiditis in a neonate. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1043–1044. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100125228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomita T, Kamio Y. Molecular biology of the pore-forming cytolysins from Staphylococcus aureus, α and γ-hemolysins and leukocidin. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1997;61:565–572. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]