Abstract

Nineteen Bartonella henselae strains and one Bartonella clarridgeiae strain were isolated from blood samples of 97 pet cats and 96 stray cats from Berlin, Germany, indicating prevalence rates of 1 and 18.7%, respectively, for B. henselae and 0 and 1%, respectively, for B. clarridgeiae. Eighteen of 19 B. henselae isolates corresponded to 16S rRNA type II. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis revealed seven different PFGE types among the feline B. henselae strains. Interestingly, all feline isolates displayed low genetic relatedness to B. henselae strain Berlin-1, which is pathogenic for humans.

Bartonella henselae is the major causative agent of cat scratch disease (CSD), bacillary angiomatosis (BA), bacteremia, and other pathological manifestations (1). Bartonella clarridgeiae has recently been described in association with CSD (11). Domestic cats are the main natural reservoir for both species (10, 11). Previous studies have demonstrated differences in prevalence rates among cats from different geographic regions, mostly correlating with climatic conditions and the type of animal population studied (3, 8–10, 16). The first objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of Bartonella infection among two different cat populations in Berlin, Germany.

(This paper includes part of A. J. Klose's doctoral thesis.)

Blood samples were collected between June 1999 and May 2000 from 193 cats in Berlin. Ninety-seven of these were pet cats brought to the School of Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital for elective procedures, and another 96 were stray cats from different neighborhoods brought to an animal asylum for neutering. One to 1.5 ml of blood was collected in a pediatric lysis-centrifugation tube (Isolator 1.5; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). A 0.1-ml portion was inoculated onto solid and broth culture media, including Columbia agar with 5% human blood, chocolate agar (Columbia base) with 10% sheep blood, and brucella broth supplemented with Fildes enrichment and hemin (18). Plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 8 weeks. Broth cultures were plated after 1 and 3 weeks on Columbia agar, and plates were incubated for a further 8 weeks. Preliminary identification of the Bartonella isolates was based on phenotypic characteristics and biochemical reactions in the Rapid ID 32 A system (Bio Merieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France). Species identification was performed for all Bartonella-like isolates by partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (approximately 420 bp) (2).

Twenty blood cultures revealed growth of Bartonella spp.; 19 isolates were identified as B. henselae, and 1 was identified as B. clarridgeiae. The Rapid ID 32A results were 000 005/7 3705 for B. henselae, indicating that some strains could not cleave proline. The B. clarridgeiae strains Ber-K185 and ATCC 51734, with the profile 000 001 3705, differed in that they hydrolyzed neither proline nor leucine-glycine. Growth characteristics of B. clarridgeiae strain Ber-K185 differed from those of B. henselae strains. Briefly, the primary isolate grew only on chocolate agar and in supplemented brucella broth, and subcultures grew inconsistently or weakly on solid media. These findings are in accordance with previous reports on the difficulties of culturing B. clarridgeiae on solid culture media (7, 8). Identification of the Ber-K185 strain was confirmed by complete 16S rRNA sequencing (1,410 bp), which revealed 100% homology to published sequences for B. clarridgeiae (8, 11).

One B. henselae strain was isolated from the pet cat population, whereas 18 B. henselae strains and one B. clarridgeiae strain were grown from the stray cat population. Prevalence rates for B. henselae were 1% (95% confidence interval [CI95], 0.98 to 3.04%) in pet cats and 18.7% (CI95, 10.94 to 26.56%) in stray cats, and those for B. clarridgeiae were 0 and 1% (CI95, −0.99 to 3.07%), respectively. The overall prevalence of Bartonella spp. was 1% in pet and 19.8% in stray cats. Higher rates of infection in stray or impounded cats have previously been reported for other geographic regions (6). Only one B. clarridgeiae strain was isolated from the 193 cats included in this study. A second isolate with high morphological similarity to the B. clarridgeiae type strain was lost on first subculture. Although we used additional broth cultures to achieve optimal growth conditions for B. clarridgeiae, we cannot exclude the possibility that some B. clarridgeiae isolates did not grow under these conditions. Nevertheless, the prevalence of B. clarridgeiae appears to be rather low among domestic cats in Berlin.

Various typing methods have been used to determine the genetic relatedness among different B. henselae isolates (5, 14, 15). Bergmans and coworkers have described two types differing in 3 bp as determined by partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (4). Type I was the most prevalent variant (75%) in tissue samples from Dutch patients with CSD, while a minority (28%) of the Dutch cats tested were infected by this variant; therefore, the authors suggested that type I isolates may be more virulent for humans than type II variants (3). We determined the 16S RNA type by partial 16S rRNA sequencing. Eighteen of the 19 feline B. henselae strains revealed sequences identical to that of the BA-TF strain and therefore corresponded to 16S RNA type II (Table 1). One B. henselae strain showed the highest homology (99.5%) with the sequence of the type I strain B. henselae Houston-1 (12). These findings are in accordance with the data of Sander et al. (17), who found one type I isolate (5.9%) among 17 feline blood culture isolates in Freiburg, Germany.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the B. henselae isolates studied

| Lane in Fig. 1A | Isolate | Clinical source | 16S RNA type | PFGE type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ATCC 49793 | HIV patient (blood) | I | A |

| 3 | Houston-1 | HIV patient (blood) | I | B |

| 4 | Berlin-1 | HIV patient (BA-lesion) | I | B |

| 5 | Berlin-2 | Cat (CSDa) | II | C5 |

| 6 | Ber-K56 | Cat | II | C1 |

| 7 | Ber-K111 | Cat | II | C1 |

| 8 | Ber-K118 | Cat | II | C4 |

| 9 | Ber-K132 | Cat | II | C1 |

| 10 | Ber-K135 | Cat | II | C2 |

| 11 | Ber-K181 | Cat | II | C2 |

| 12 | Ber-K182 | Cat | II | C1 |

| 13 | Ber-K169 | Cat | II | C3 |

| 14 | Ber-K108 | Cat | II | D1 |

| 15 | Ber-K116 | Cat | II | D1 |

| 16 | Ber-K158 | Cat | II | D2 |

| 17 | Ber-K156 | Cat | II | E1 |

| 18 | Ber-K161 | Cat | II | E2 |

| 19 | Ber-K123 | Cat | II | F |

| 20 | Ber-K172 | Cat | II | G |

| 21 | Ber-K186 | Cat | I | F |

| 22 | Ber-K143 | Cat | II | H |

| 23 | Ber-K153 | Cat | II | I |

| 24 | Ber-K193 | Cat | II | G |

Blood culture isolate from the pet cat of a patient with CSD.

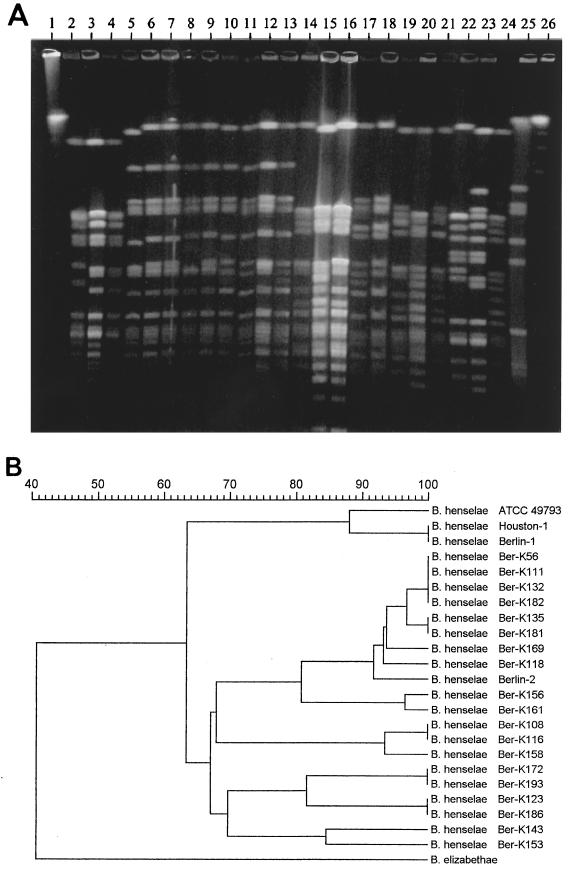

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) has been found to be the most powerful method for intraspecies differentiation of Bartonella isolates (15, 17). By using this method, we recently (2) reported that the B. henselae isolate Berlin-1, which was originally isolated from BA lesions of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patient in Berlin, is genetically indistinguishable from the B. henselae strain Houston-1 (12). This finding raised the question whether some strains are more likely than others to cause a particular type of pathology and whether a small number of strains account for a disproportionate amount of disease (13). Therefore, we determined the genetic relationship among the feline B. henselae isolates from Berlin and compared their genetic fingerprints to those obtained from the Berlin-1 strain. Because further human-derived isolates were not available from Berlin or elsewhere in Germany, the B. henselae strains Houston-1 (ATCC 49882) and Oklahoma (ATCC 49793) (19), which are pathogenic for humans (human pathogenic), were also included in this study. Digestion of whole chromosomal DNA with SmaI and PFGE were performed as previously described (2). Visual analysis of banding patterns of the feline isolates revealed seven different PFGE types differing in four or more bands from each other (Fig. 1A). These PFGE types were considered to represent genetically unrelated variants, indicating a considerable genetic heterogeneity among the feline isolates (Table 1). As previously shown (2), the human-pathogenic B. henselae strains Berlin-1 and Houston-1 were identical and showed high similarity (88%) to the Oklahoma strain (Fig. 1). Interestingly, none of the feline isolates revealed a banding pattern identical or similar to that obtained from the Berlin-1 isolate. Computer-assisted analysis of the fingerprints revealed that the feline isolates displayed only 63% similarity to the human-pathogenic isolates (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) DNA fingerprint analysis of the feline and human-pathogenic B. henselae isolates and the B. elizabethae strain ATCC 49927 by PFGE. (B) Dendrogram of the fingerprints as determined by unweighted pair group using mathematical averages. Lane 1, lambda ladder; lanes 2 to 4, human-pathogenic B. henselae isolates ATCC 49793 (Oklahoma), Houston-1, and Berlin-1, respectively; lanes 5 to 24, feline blood culture isolates of B. henselae; lane 25, B. elizabethae; lane 26, Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome marker.

Although we studied cats from a limited geographic area during a short time interval, the prevalence of the Berlin-1 strain appears to be low (<0.05%). Our findings are in line with data from the Freiburg area of Germany (17) showing that none of 17 feline B. henselae isolates were identical or similar to the Houston-1 strain, which is genetically indistinguishable from the Berlin-1 strain. It is therefore remarkable that the single human-pathogenic B. henselae isolate available from an immunocompromised patient in Germany is genetically highly related to two B. henselae strains isolated from a similar group of patients from another continent. To date, more human-pathogenic B. henselae strains are not available from Germany. Further investigations should include more human-pathogenic and feline B. henselae isolates from other geographic regions in order to determine whether certain strains possess a specific affinity to humans and/or immunocompromised human hosts.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rRNA sequence of the Ber-K185 strain has been submitted to the EMBL nucleotide sequence database (accession number AJ299444).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 325-4471-02/50 from the German Federal Ministry of Health.

We thank Dagmar Piske for expert technical assistance and Ralf Ignatius for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson B E, Neuman M A. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203–219. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvand M, Wendt C, Regnath T, Ullrich R, Hahn H. Characterization of Bartonella henselae isolated from bacillary angiomatosis lesions in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient in Germany. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1296–1299. doi: 10.1086/516348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmans A M, de Jong C M, van Amerongen G, Schot C S, Schouls L M. Prevalence of Bartonella species in domestic cats in The Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2256–2261. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2256-2261.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmans A M, Groothedde J W, Schellekens J F, van Embden J D, Ossewaarde J M, Schouls L M. Etiology of cat scratch disease: comparison of polymerase chain reaction detection of Bartonella (formerly Rochalimaea) and Afipia felis DNA with serology and skin tests. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:916–923. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergmans A M, Schellekens J F, van Embden J D, Schouls L M. Predominance of two Bartonella henselae variants among cat-scratch disease patients in The Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:254–260. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.254-260.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomel B B, Abbott R C, Kasten R W, Floyd H K, Kass P H, Glaser C A, Pedersen N C, Koehler J E. Bartonella henselae prevalence in domestic cats in California: risk factors and association between bacteremia and antibody titers. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2445–2450. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2445-2450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarridge J E, III, Raich T J, Pirwani D, Simon B, Tsai L, Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Regnery R, Zollo A, Jones D C, Rambo C. Strategy to detect and identify Bartonella species in routine clinical laboratory yields Bartonella henselae from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient and unique Bartonella strain from his cat. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2107–2113. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2107-2113.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller R, Artois M, Xemar V, De B D, Gehin H, Jaulhac B, Monteil H, Piemont Y. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in stray cats. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1327–1331. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1327-1331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jameson P, Greene C, Regnery R, Dryden M, Marks A, Brown J, Cooper J, Glaus B, Greene R. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae antibodies in pet cats throughout regions of North America. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1145–1149. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koehler J E, Glaser C A, Tappero J W. Rochalimaea henselae infection. A new zoonosis with the domestic cat as reservoir. JAMA. 1994;271:531–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kordick D L, Hilyard E J, Hadfield T L, Wilson K H, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J, Breitschwerdt E B. Bartonella clarridgeiae, a newly recognized zoonotic pathogen causing inoculation papules, fever, and lymphadenopathy (cat scratch disease) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1813–1818. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1813-1818.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regnery R L, Anderson B E, Clarridge III J E, Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Jones D C, Carr J H. Characterization of a novel Rochalimaea species, R. henselae sp. nov., isolated from blood of a febrile, human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:265–274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.265-274.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Relman D A. Are all Bartonella henselae strains created equal? Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1300–1301. doi: 10.1086/516347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Hamill R J, Houston E D, Georghiou P R, Clarridge J E, Regnery R L, Koehler J E. Genomic fingerprinting of Bartonella species by repetitive element PCR for distinguishing species and isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1089–1093. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1089-1093.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roux V, Raoult D. Inter- and intraspecies identification of Bartonella (Rochalimaea) species. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1573–1579. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1573-1579.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander A, Buhler C, Pelz K, von Cramm E, Bredt W. Detection and identification of two Bartonella henselae variants in domestic cats in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:584–587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.584-587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sander A, Ruess M, Bereswill S, Schuppler M, Steinbrueckner B. Comparison of different DNA fingerprinting techniques for molecular typing of Bartonella henselae isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2973–2981. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2973-2981.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartzman W A, Nesbit C A, Baron E J. Development and evaluation of a blood-free medium for determining growth curves and optimizing growth of Rochalimaea henselae. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1882–1885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1882-1885.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slater L N, Welch D F, Hensel D, Coody D W. A newly recognized fastidious gram-negative pathogen as a cause of fever and bacteremia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1587–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]