Abstract

Eimeria maxima (E. maxima) is one of the most prevalent species that causes chicken coccidiosis on chicken farms. During apicomplexan protozoa invasion, rhomboid-like proteins (ROMs) cleave microneme proteins (MICs), allowing the parasites to fully enter the host cells, which suggests that ROMs have the potential to be candidate antigens for the development of subunit or DNA vaccines against coccidiosis. In this study, a recombinant protein of E. maxima ROM5 (rEmROM5) was expressed and purified and was used as a subunit vaccine. The eukaryotic expression plasmid of pVAX–EmROM5 was constructed and was used as a DNA vaccine. Chickens who were two weeks old were vaccinated with the rEmROM5 and pVAX–EmROM5 vaccines twice, with a one-week interval separating the vaccination periods. The transcription and expression of pVAX–EmROM5 in the injected sites were detected through reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and Western blot (WB) assays. The cellular and humoral immune responses that were induced by EmROM5 were determined by detecting the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, the cytokine levels, and the serum antibody levels. Finally, vaccination-challenge trials were conducted to evaluate the protective efficacy of EmROM5 in forms of the recombinant protein (rEmROM5) and in the DNA plasmid (pVAX–EmROM5) separately. The results showed that rEmROM5 was about 53.64 kDa, which was well purified and recognized by the His-Tag Mouse Monoclonal antibody and the chicken serum against E. maxima separately. After vaccination, pVAX–EmROM5 was successfully transcribed and expressed in the injected sites of the chickens. Vaccination with rEmROM5 or pVAX–EmROM5 significantly promoted the proportion of CD4+/CD3+ and CD8+/CD3+ T lymphocytes, the mRNA levels of the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, TNF SF15, and IL-10, and specific IgG antibody levels compared to the control groups. The immunization also significantly reduced the weight loss, oocyst production, and intestinal lesions that are caused by E. maxima infection. The anticoccidial index (ACI)s of the vaccinated groups were beyond 160, showing moderate protection against E. maxima infection. In summary, EmROM5 was able to induce a robust immune response and effective protection against E. maxima in chickens in the form of both a recombinant protein and DNA plasmid. Hence, EmROM5 could be used as a candidate antigen for DNA vaccines and subunit vaccines against avian coccidiosis.

Keywords: Eimeria maxima, rhomboid-like protein 5, immunogenicity, protective efficacy

1. Introduction

Chicken coccidiosis, a globally distributed parasitic disease, is caused by the infection of single or multiple Eimeria species, which parasitize in the intestinal epithelial cells of chickens. After being infected by Eimeria, chickens typically demonstrate clinical symptoms that usually include loss of appetite, slow growth in weight, diarrhea, and death, etc. [1,2]. All of these pathological conditions eventually lead to a greatly reduced feed utilization rate and growth or laying rate. In severe cases, the mortality rate is as high as 80%, which brings huge losses to the world poultry industry. According to a recent survey, the global cost of coccidiosis in 2016 was estimated to be GBP 10.36 billion, including the losses that were incurred in the production process and the costs of prevention and treatment [3]. There are seven species of Eimeria that are recognized in the world, and E. maxima is one of the most prevalent species all over the world [4,5,6]. In China, the positive rates of E. maxima from 171 farms in Anhui province and 50 farms in Shandong province were 54.67% and 68%, respectively [7,8]. In Australia, 125 samples of commercial chicken flocks from different states and territories were tested, and it was found that the above proportion of E. maxima was 58% [9]. Samples from 251 farms in the south of Brazil were collected, and fecal examination showed that E. maxima was 63.7% [10].

At present, the main methods to control chicken coccidiosis include the application of anticoccidial drugs and vaccination with live vaccines [11,12]. Although these control strategies play important roles in preventing and controlling the outbreak and epidemic of chicken coccidiosis, alternative control measures are urgently needed due to the emergence of multiple problems such as drug-resistant strains, drug residues in poultry products, as well as the safety issues and high production costs of live vaccines [13]. New vaccines, including DNA vaccines and subunit vaccines, have been suggested as effective strategies for controlling coccidiosis due to their low production cost and high levels of safety, etc. The identification of antigens with good immunogenicity and protective efficacy is the prerequisite for the development of new-generation vaccines. To date, couples of Eimeria antigens have been tested as vaccine candidates and have showed promising protective efficacies [14]. However, reports on protective antigens from E. maxima are limited compared to E. tenella and E. acervulina.

Rhomboid-like proteins (ROMs), which are conserved intramembrane serine proteases, are involved in multiple biological activities of various organisms [15]. In Apicomplexan protozoa, ROMs were found to cleave various adhesins that were secreted by the parasites that were mediating the contact and recognition with host cells, promoting the adhesion and invasion of protozoa to host cells [16]. Previous studies on protozoa ROMs have confirmed this function. In Toxoplasma gondii, ROMs were reported to cleave the adhesins of TgAMA1, TgMIC2, TgMIC6, and TgMIC12. In Plasmodium falciparum, PfAMA1, PfRh1, and PfRh4 were shown to be the substrates of ROMs in vivo [15]. As for the Eimeria, EtROM3 was reported to be able to cleave EtMIC4 in E. tenella [17]. Given the key role of ROMs in the protozoa invasion process, the protective efficacy of ROMs was evaluated and showed promising protection against protozoa parasites in a couple of studies [18,19,20,21].

In our study, the rhomboid-like protein 5 gene of Eimeria maxima (EmROM5) was ligated with prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression vectors to produce the EmROM5 recombinant protein and DNA plasmid. Subsequently, the immune responses and protective efficacy that was induced by rEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5 were evaluated, respectively. The results demonstrated the importance of EmROM5 in the development of new vaccines against avian coccidiosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmids, Parasites and Animals

The pET-32a (+) plasmid and the pVAX1.0 plasmid were purchased from Novagen (Darmstadt, Germany) and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. E. coli competent cells of DH5α and BL21 (DE3) were obtained from Vazyme (Nanjing, China). One-day-old chicks (Hy-line Variety White) were purchased from a commercial hatchery in Nanjing and were raised in wire cages in coccidia-free conditions. Water and feed without anticoccidial drugs were provided throughout the experiment. Thirty-day-old rats (SD) were purchased from the Qinglong Mountain Breeding Farm in Nanjing. E. maxima was propagated by passing through the chickens seven days before the experiment, following previous reports [22]. All animal experiments were conducted with the permission of the Committee on Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics of Nanjing Agricultural University.

2.2. Cloning of EmROM5 Gene

Mini glass beads (0.5 mm diameter) were used to break the oocyst wall in E. maxima, following previous reports [22]. After that, the total mRNA was extracted with the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (OMEGA, Norcross, GA, USA). Next, mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the HiScript IIQ RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Subsequently, PCR was performed to amplify the EmROM5 gene with the cDNA and specific primers (Table 1). Since the full-length of the EmROM5 gene was not expressed in vitro, the non-transmembrane amino acid sequence of EmROM5 (ntmEmROM5, amino acid sequence: 1-321aa) was selected using TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/, accessed on 15 April 2017) online software for prokaryotic vector construction, protein expression, and further study. The specific primers for ntmEmROM5 and EmROM5 are shown in Table 1. The program was as below: 94 °C, 5 min; 35 cycles (94 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 57 s for ntmEmROM5 or 72 °C, 85 s for EmROM5); and 72 °C, 7 min. The bands of the products were observed by means of 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 1.

Specific primers of E. maxima ROM5.

| Gene | Primer | Size (bp 3) |

|---|---|---|

| ntmEmROM5 1 | Forward: 5’-CCGGAATTCATGTCTTCCCCCATTG-3’ | 963 |

| Reverse: 5’-CCCTCGAGATGCAAAAAGGAGGCCCAAAAGAC-3’ | ||

| EmROM5 2 | Forward: 5’-CCGGAATTCATGTCTTCCCCCATTG-3’ | 1461 |

| Reverse: 5’-AAATATGCGGCCGCTCAAGTAAACTT-3’ |

1 Non-transmembrane E. maxima ROM5; 2 E. maxima ROM5; 3 base pair.

2.3. Construction of Recombinant Plasmids pET-32a-ntmEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5

The PCR products of ntmEmROM5 and EmROM5 were recovered using the Gel Extraction Kit 200 (OMEGA). Next, ntmEmROM5, EmROM5, the pET-32a vector, and the pVAX1.0 vector were digested by the endonuclease of EcoR I and Xho I in 10 × H Buffer (Takara, Dalian, China) at 37 °C. The digested fragments of ntmEmROM5 and EmROM5 were ligated into the pET-32a and pVAX1.0 vectors to construct pET-32a-ntmEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5, respectively. The ligation products were transformed into DH5α cells for cloning purposes. Finally, these two plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing and endonuclease digestion. The obtained DNA sequences were compared using the online tool BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), which was developed by the NCBI. The recombinant plasmid of pVAX-EmROM5 and the empty vector of pVAX for the vaccination trials were prepared using FastPure EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kits (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Preparation of NtmEmROM5 Recombinant Protein (rEmROM5), Chicken Anti-E. maxima Serum and Rat Anti-rEmROM5 Serum

After the transformation of the pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 plasmid into BL21 (DE3), IPTG (1 mM) was used to induce the expression of rEmROM5. The purification of rEmROM5 was performed using the HisTrap TM FF Column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Endotoxins were removed from rEmROM5 using the Endotoxin Removal Kit (Genscript, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the purified rEmROM5 was measured with the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein was diluted to 500 μg/mL with PBS buffer and stored at −80 °C. Simultaneously, the pET-32a tag protein was obtained using the same procedure.

To prepare chicken anti-E. maxima serum, fourteen-day-old chickens were artificially infected with 1 × 104 E. maxima oocysts 5 times at one-week intervals by means of oral administration. The blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture 7 days after the last infection day. To prepare rat anti-rEmROM5 serum, 30-day-old rats were immunized with an emulsion consisting of 0.5 mL (500 μg/mL) rEmROM5 and 0.5 mL of Freund’s complete adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) through subcutaneous injection on the back. A total of 14 days later, the rats were immunized with another emulsion consisting of 0.5 mL rEmROM5 and 0.5 mL Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. After that, the rats were given three more immunization using the same dose and component as the last immunization cycle, and these injections were given at one-week intervals. Finally, blood was collected from the fundus vein, the serum titer was detected by indirect ELISA, and after the titer reached the appropriate level, the rats were killed for blood collection, and the serum was separated and stored at −70 °C.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis of rEmROM5

The recombinant protein of EmROM5 was analyzed by Western blot assays. After the SDS-PAGE of rEmROM5, it was transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Merck Millipore, Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Ireland). Then, the membranes were incubated in the primary antibody of chicken anti-E. maxima serum (1:50 dilution) or His-Tag Mouse Monoclonal antibody (1:8000 dilution, Proteintech, Wuhan, China)at ambient temperature for 4 h separately, and incubated in the secondary antibody of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgG (1:4000 dilution, Biodragon-immunotech, Beijing, China) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (1:10,000 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C for 1.5 h separately. Meanwhile, uninfected chicken serum was set for negative control as a primary antibody. Finally, an Enhanced HRP-DAB substrate chromogenic kit (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China) or ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used for color rendering.

2.6. Reverse Transcription PCR and Western Blot Analysis of Transcription and Expression of pVAX-EmROM5 In Vivo

Fourteen-day-old chickens were injected with pVAX–EmROM5 or pVAX1.0 in the leg muscle with a dose of 100 μg per chicken. The injection sites were marked. After 7 days, muscles were collected from the injection sites and non-injection sites. To detect the transcription of EmROM5, 1 g of muscle was removed from the injection sites and was ground with 1 mL RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa) for 30 min in ice water. The total mRNA of the muscles were extracted following the instructions for the RNAiso Plus reagent, and DNase I (TaKaRa) was used to eliminate the residual recombinant plasmid of the muscles. The EmROM5 gene primers (Table 1) were used for RT-PCR with the mRNA products as templates. Electrophoresis was conducted to detect the product bands to reflect the transcription of EmROM5.

To detect the expression of EmROM5, the removed muscles were treated with RIPA Lysis Buffer (Strong, CWBIO, Beijing, China) for 2 h and were centrifuged at 12,000· g for 15 min, and the supernatant was used for SDS-PAGE. During the WB analysis to detect the level of protein expression, rat anti-rEmROM5 serum (1:50 dilution) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (1:4000 dilution, Biodragon-immunotech, Beijing, China) were used as the primary antibody and secondary antibody, respectively. Meanwhile, negative rat serum was set for the negative control as a primary antibody.

2.7. Determination of Immune Response Induced by EmROM5 in Chickens

2.7.1. Animal Immunization

There were five groups of fourteen-day-old chickens with similar weights. Experimental group chickens were vaccinated with 200 μg of rEmROM5 or 100 μg of pVAX–EmROM5 by injecting into the leg muscles, respectively. Control group chickens were injected with the pET-32a tag protein, pVAX1.0 plasmid, or PBS, respectively. After seven days, a booster immunization was performed using the same procedure.

2.7.2. Determination of EmROM5-Induced Changes in Spleen T Lymphocyte Subpopulations by Flow Cytometry

On the 7th day after each immunization, five chickens in each group were dissected, and their spleens were removed. The spleens were well ground in PBS buffer and were filtered with a 200-mesh cell sieve; the filtrate was slowly added along the wall into a 10 mL sharp-bottomed glass centrifuge tube containing 5 mL of 37 °C pre-warmed lymphocyte separation solution (TBDscience, Tianjin, China) and was then centrifuged at 720 g for 16 min; the middle white layer of the cells was transferred into new centrifuge tubes and were washed twice with PBS buffer. Finally, the lymphocytes were counted using a blood counting chamber, and the density was adjusted to 1 × 107 cell/mL by PBS buffer. An amount of 100 μL of counted lymphocytes were taken from each group and were placed into 2 mL centrifuge tubes; lymphocytes from all of the groups were double stained with mouse anti-chicken CD3-FITC (Southernbiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and mouse anti-chicken CD4-PE or mouse anti-chicken CD8-PE by incubating at 4 °C for 45 min under dark conditions; in addition, lymphocytes from the PBS control group were treated with blank or single stain for template adjustment. The sample test was run using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

2.7.3. Determination of EmROM5-Induced Changes in Cytokines by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Specific PCR primers of GAPDH, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, TNF SF15, TGF-β, and IL-10 cytokines were designed and synthesized (Table 2). The total mRNA of the spleen lymphocytes from blank chickens was extracted and reverse-transcribed into cDNA as a template. A screening experiment with a series of template concentration gradients was conducted to determine the amplification efficiencies of the gene primers [23]. There were 18 reactions per primer pair, the template was diluted to 5 different concentration gradients, each gradient was repeated 3 times, and 3 replicates of no template control (NTC) were set up. The amplification efficiency (E) and average Cq (ΔCq) of the primers were calculated, and the cytokine primers ranging in amplification efficiency from 90% to 110% and with a ΔCq of 3 or greater were selected. A slope of −3.32 represents 100% PCR efficiency, and the formula is as follows: E = 10−1/slope − 1 [24]; ΔCq = Cq(NTC) − Cq(lowest input). The primers with good amplification efficiency were used to determine the samples of the experimental groups. The reaction system and reaction procedure refer to the instruction of the ChamQTM SYBR qPCR Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The relative quantification of the cytokine mRNA compared to that of the internal reference gene (n-fold change to the PBS buffer control group) was estimated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [25].

Table 2.

Specific primer sequences of quantitative real-time PCR.

| RNA Target | Primer Sequence | Accession No. | Amplification Efficiency (%) |

Correlation Coefficient (r2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | GGTGGTGCTAAGCGTGTTAT | K01458 | 100.74% | 0.9917 |

| ACCTCTGTCATCTCTCCACA | ||||

| IL-2 | TAACTGGGACACTGCCATGA | AF000631 | 102.44% | 0.9921 |

| GATGATAGAGATGCTCCATAAGCTG | ||||

| IL-4 | ACCCAGGGCATCCAGAAG | AJ621735 | 99.09% | 0.9936 |

| CAGTGCCGGCAAGAAGTT | ||||

| IL-10 | GGAGCTGAGGGTGAAGTTTGA | AJ621614 | 99.19% | 0.9923 |

| GAAGCGCAGCATCTCTGACA | ||||

| IL-17 | ACCTTCCCATGTGCAGAAAT | EF570583 | 100.24% | 0.994 |

| GAGAACTGCCTTGCCTAACA | ||||

| IFN-γ | AGCTGACGGTGGACCTATTATT | Y07922 | 103.07% | 0.9868 |

| GGCTTTGCGCTGGATTC | ||||

| TGF-β | CGGGACGGATGAGAAGAAC | M31160 | 102.79% | 0.9815 |

| CGGCCCACGTAGTAAATGAT | ||||

| TNF SF15 | GCTTGGCCTTTACCAAGAAC | NM001024578 | 100.57% | 0.993 |

| GGAAAGTGACCTGAGCATAGA |

2.7.4. Determination of EmROM5-Specific IgG Antibody Level by Indirect ELISA

One week after the first and the second immunizations, blood was drawn from the heart of every chicken. The fresh blood was placed in an incubator that was set at 37 °C for 2 h and was then placed in a fridge that was set at 4 °C for 4 h. After centrifuging at 540× g for 8 min, the serum was separated and stored at −30 °C. Then, the rEmROM5-specific IgG serum level was determined by indirect ELISA on the basis of the reported method [26]. First, flat-bottomed 96-well plates (MarxiSorp, Nunc, Denmark) were coated with rEmROM5 that had been diluted in the coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH = 9.6). Second, the chicken serum that had been collected in the previous step (1:50 dilution) was used as the primary antibody, and the HRP-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgG (1:4000 dilution) was as the secondary antibody. Third, color production was conducted with 3, 3’, 5, 5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, TIANGEN), and the OD450 was determined using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Multiskan FC).

2.8. Assessment of Protective Efficacy of EmROM5 against Challenge with E. maxima

Two vaccination-challenge trials were performed to evaluate the protective efficacies of rEmROM5 (Trial 1) and pVAX–EmROM5 (Trial 2) separately; chickens with similar growth status were randomly divided into eight groups (Table 3). The experimental groups had 200 μg of rEmROM5 (without adjuvant) or 100 μg of naked plasmid pVAX–EmROM5 injected into their leg muscles at two weeks and three weeks of age, respectively. The challenged and unchallenged control groups were injected with PBS. The pET-32a tag protein and pVAX1.0 control groups were injected with the same amount of tag protein or empty plasmid as the corresponding experimental groups. At four weeks of age, the two groups of unchallenged chickens were given PBS orally, the other six groups were orally infected with 1 × 105 freshly sporulated E. maxima oocysts [27]. All of the chickens were slaughtered six days post challenge infection.

Table 3.

Protective efficacy of rEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5 against challenge with E. maxima (n = 30, value = mean ± SD).

| Trials | Groups | Average Body Weight Gain (g) | Relative Body Weight Gain (%) | Mean Lesion Score | Average OPG (×105) | ACI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unchallenged control | 56.91 ± 10.24 a | 100 a | 0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 a | 200 |

| Challenged control | 27.21 ± 8.52 c | 47.81 c | 2.84 ± 0.88 c | 2.25 ± 0.94 c | 79.41 | |

| pET-32a tag protein control | 29.46 ± 11.25 c | 51.77 c | 2.66 ± 0.93 c | 2.15 ± 0.97 c | 85.17 | |

| rEmROM5 | 49.36 ± 11.35 b | 86.73 b | 1.46 ± 0.52 b | 0.56 ± 0.48 b | 171.13 | |

| 2 | Unchallenged control | 79.32 ± 9.59 a | 100 a | 0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 a | 200 |

| Challenged control | 39.28 ± 9.72 c | 49.53 c | 2.83 ± 0.72 c | 2.81 ± 0.13 c | 81.23 | |

| pVAX1.0 control | 38.19 ± 15.39 c | 48.15 c | 2.75 ± 0.62 c | 2.80 ± 0.16 c | 80.65 | |

| pVAX–EmROM5 | 65.95 ± 4.96 b | 83.14 b | 1.25 ± 0.75 b | 0.67 ± 0.19 b | 169.64 |

a–c Means in the same columns marked with the same letter indicates that the difference between treatments is not significant (p > 0.05). Means in the same columns marked with a different letter indicates a significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05).

The survival rate, intestinal lesion score, weight gain, and oocysts output were recorded and were used to evaluate the protective efficacy of the vaccines. The survival rate was counted as follows: the amount of surviving chickens/the amount of initial chickens. The enteric lesion score was recorded following the method described by Johnson and Reid (1970) [28]. Oocysts of per gram feces (OPG) were determined via McMaster’s counting technique [29,30]. The anticoccidial index (ACI) is a comprehensive index to evaluate the anticoccidial efficacy of vaccines/drugs and is calculated as follows: (survival rate + relative rate of weight gain) − (lesion value + oocyst value) [2,31].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using the one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software. Since lesion scores and oocyst output do not follow the normal distribution, statistical analyses were carried out with pairwise comparisons using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Data were presented as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Cloning of NtmEmROM5 and EmROM5, Construction of pET-32a-ntmEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5

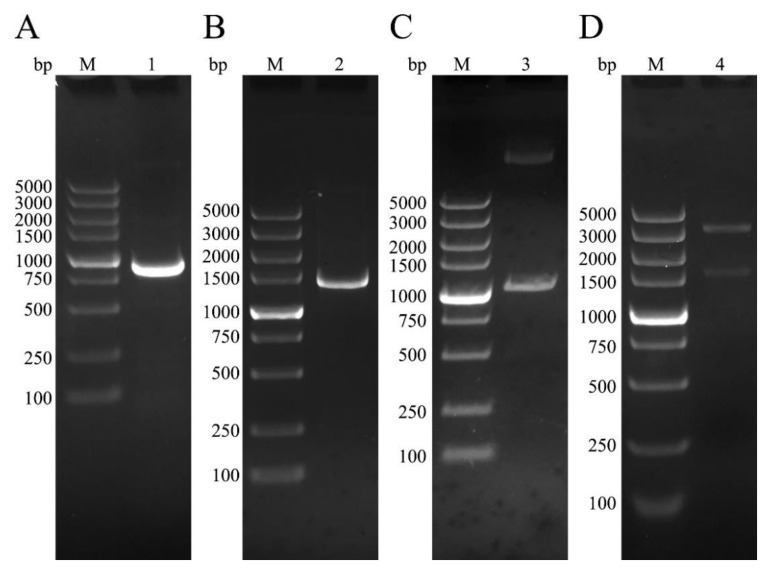

EmROM5 and ntmEmROM5 were amplified through RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 1, agarose gel electrophoresis showed bands that were approximately 963 bp and 1461 bp in size that were equal to the molecular weights of ntmEmROM5 (Figure 1A, Lane 1) and EmROM5(Figure 1B, Lane 2), respectively. Recombinant plasmids of pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 and pVAX–EmROM5 were constructed and identified by enzyme digestion, two bands with the sizes of approximately 963 bp (Figure 1C, Lane 3) and 1461 bp (Figure 1D, Lane 4) were observed, which were consistent with the sizes of ntmEmROM5 and EmROM5, respectively. Moreover, the sequencing results showed that the nucleotide sequences of the two genes shared 100% similarity with the sequence in GenBank (ID: XM_013478359.1).

Figure 1.

Gene cloning and vector construction. (A) RT-PCR amplification of ntmEmROM5. M, DNA molecular weight standard of DL5000. Lane 1, amplification products of ntmEmROM5 (963 bp). (B) RT-PCR amplification of EmROM5. M, DNA molecular weight standard of DL2000. Lane 2, amplification products of EmROM5 (1461 bp). (C) Enzyme digestion identification of pET-32a–ntmEmROM5. M, DNA molecular weight standard of DL2000. Lane 3, enzyme digestion identification of pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 (963 bp). (D) Enzyme digestion identification of pVAX–EmROM5. M, DNA molecular weight standard of DL5000. Lane 4, enzyme digestion identification of pVAX-EmROM5 (1461 bp).

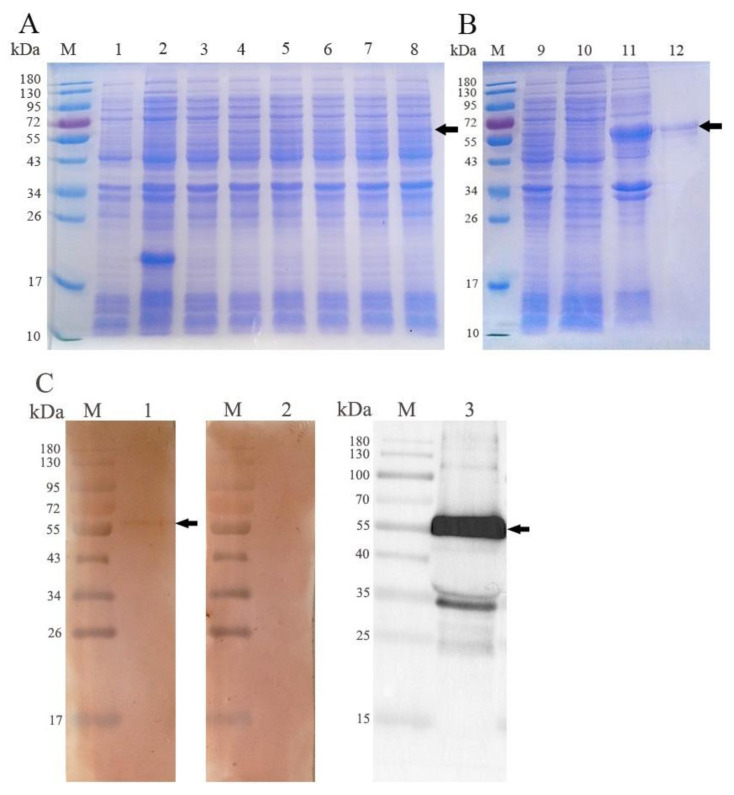

3.2. Expression and Western Blot Analysis of rEmROM5

The rEmROM5 was expressed in E. coli and was analyzed through WB analysis. As shown in Figure 2, the expression of rEmROM5 was positively correlated with the induction time (Figure 2A, Lane 4–8). The expressed rEmROM5 was mainly distributed in the inclusion bodies of the host bacteria (Figure 2B, Lane 11). After purification, SDS-PAGE showed a single protein band close to 53.64 kDa, which is consistent with the total molecular weight of the ntmEmROM5 protein (35.31 kDa) and pET-32a tag protein (18.33 kDa) (Figure 2B, Lane 12). WB analysis showed that rEmROM5 was recognized by His-Tag Mouse Monoclonal antibody (Figure 2C, Lane 3) and chicken serum against E. maxima (Figure 2C, Lane 1) separately. Meanwhile, rEmROM5 was not recognized by the negative serum (Figure 2C, Lane 2). The original images for Figure 2C are shown in Figures S1–S3.

Figure 2.

Expression of rEmROM5 and Western blot analysis. (A) Induction of rEmROM5 (53.64 kDa) by IPTG for 1–5 h. M, protein standard molecular weight. Lane 1, pET-32a-transfected bacteria before the induction of IPTG. Lane 2, pET-32a-transfected bacteria induced by IPTG for 5 h. Lane 3, pET-32a–ntmEmROM5-transfected bacteria before the induction of IPTG. Lanes 4–8, pET-32a–ntmEmROM5-transfected bacteria induced by IPTG for 1–5 h. (B) Purification of rEmROM5 (53.64 kDa). M, protein standard molecular weight. Lane 9, pET-32a–ntmEmROM5-transfected bacteria induced by IPTG for 5 h. Lane 10, cell lysate supernatant of pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 bacterial liquid after 5 h induction of IPTG. Lane 11, cell lysate sediment of pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 bacterial liquid after 5 h induction of IPTG. Lane 12, pET-32a–ntmEmROM5 recombinant protein (rEmROM5, 53.64 kDa) after purification. (C) WB analysis of rEmROM5 (53.64 kDa). M, protein standard molecular weight. Lane 1, recognition of rEmROM5 (53.64 kDa) by anti-E. maxima chicken serum. Lane 2, uninfected chicken serum control. Lane 3, recognition of rEmROM5 (53.64 kDa) by His-Tag Mouse Monoclonal antibody.

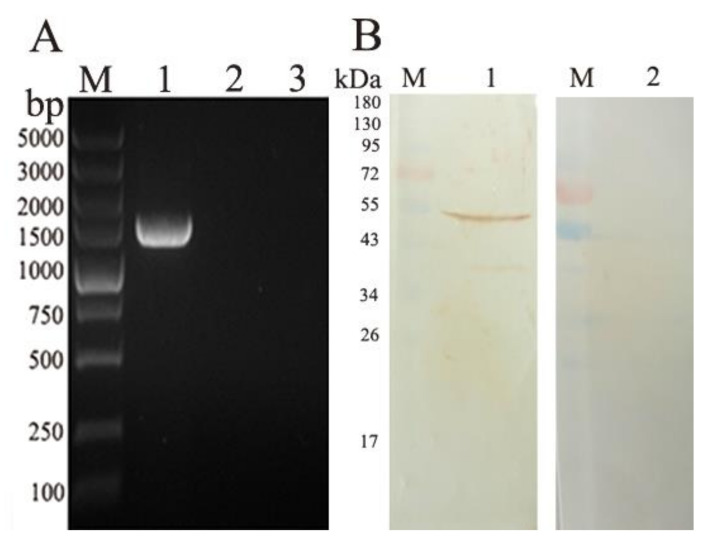

3.3. Transcription and Expression of pVAX-EmROM5 in the Injection Site Muscles of Chickens

RT-PCR was used to detect the transcription of the EmROM5 gene in the injection site muscles of the chickens. In Figure 3A, a DNA band of approximately 1461 bp was detected from the pVAX–EmROM5-injected muscles (Figure 3A, Lane 1), and there were no bands in the samples of the pVAX l.0-injected muscles and non-injected muscles (Figure 3A, Lanes 2 and 3). WB analysis was used to detect EmROM5 gene expression in the injected muscles. As per the results in Figure 3B, a protein band of 53.57 kDa that is consistent with the molecular weight of the EmROM5 protein was detected from the pVAX–EmROM5-injected muscles (Figure 3B, Lane 1), and no bands are visible for the negative control (Figure 3B, Lane 2). These results indicate that successful pVAX–EmROM5 transcription and expression of occurred in the injected muscles. The original images for Figure 3B are shown in Figure S4 and Figure S5.

Figure 3.

Transcription and expression of pVAX–EmROM5 in the injected muscles in chickens. (A) Transcription detection of pVAX–EmROM5 in the injected muscles by RT-PCR. M, DNA molecular weight standard of DL5000. Lane 1, PCR product of EmROM5 (1461 bp) from pVAX–EmROM5 injection site muscles. Lane 2, pVAX1.0 injection control. Lane 3, non-injected control. (B) Expression detection of EmROM5 in the injected muscles by WB. M, protein standard molecular weight. Lane 1, recognition of EmROM5 (53.57 kDa) in pVAX–EmROM5-injected muscles by anti-rEmROM5 rat serum. Lane 2, negative rat serum control.

3.4. Changes of CD4+/CD3+ and CD8+/CD3+ T Lymphocyte Subpopulation in the EmROM5 Immunized Chickens

The proportions of the T lymphocyte subpopulation the spleens were detected by flow cytometry to reflect the changes that were induced in the T lymphocytes by EmROM5. The results are shown in Table 4. Compared to the pET-32a tag protein and PBS groups, in the pVAX1.0 and PBS groups, the two proportions of T lymphocytes in the rEmROM5- and pVAX–EmROM5-immunized groups were significantly increased seven days after these two immunizations (p < 0.05). There is no difference in the two T lymphocyte proportions between the pET-32a tag protein, pVAX1.0, and PBS groups in the same set of data (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Quantification of T lymphocyte subpopulations in spleen seven days after immunizations (n = 5, value = mean ± SD).

| Marker | Groups | 1st Immunization | 2nd Immunization |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+/CD3+ | PBS buffer | 18.27 ± 0.21 a | 19.47 ± 3.21 a |

| pET-32a tag protein | 20.90 ± 1.64 a | 23.28 ± 1.62 a | |

| rEmROM5 | 27.75 ± 1.35 bc | 30.07 ± 0.57 b | |

| PBS buffer | 10.18 ± 0.87 a | 14.13 ± 1.50 a | |

| pVAX1.0 | 11.50 ± 2.05 a | 16.45 ± 2.05 a | |

| pVAX-EmROM5 | 22.57 ± 1.85 b | 27.51 ± 4.95 b | |

| CD8+/CD3+ | PBS buffer | 21.45 ± 0.72 a | 22.80 ± 5.20 a |

| pET-32a tag protein | 22.37 ± 1.53 a | 25.93 ± 3.39 a | |

| rEmROM5 | 35.20 ± 5.20 b | 43.59 ± 6.76 b | |

| PBS buffer | 13.00 ± 1.65 a | 13.78 ± 1.61 a | |

| pVAX1.0 | 15.60 ± 1.13 b | 17.24 ± 0.42 a | |

| pVAX-EmROM5 | 22.37 ± 0.17 c | 31.40 ± 4.48 b |

a–c Means in the same columns marked with the same letter indicates that the difference between treatments is not significant (p > 0.05). Means in the same columns marked with a different letter indicates a significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05).

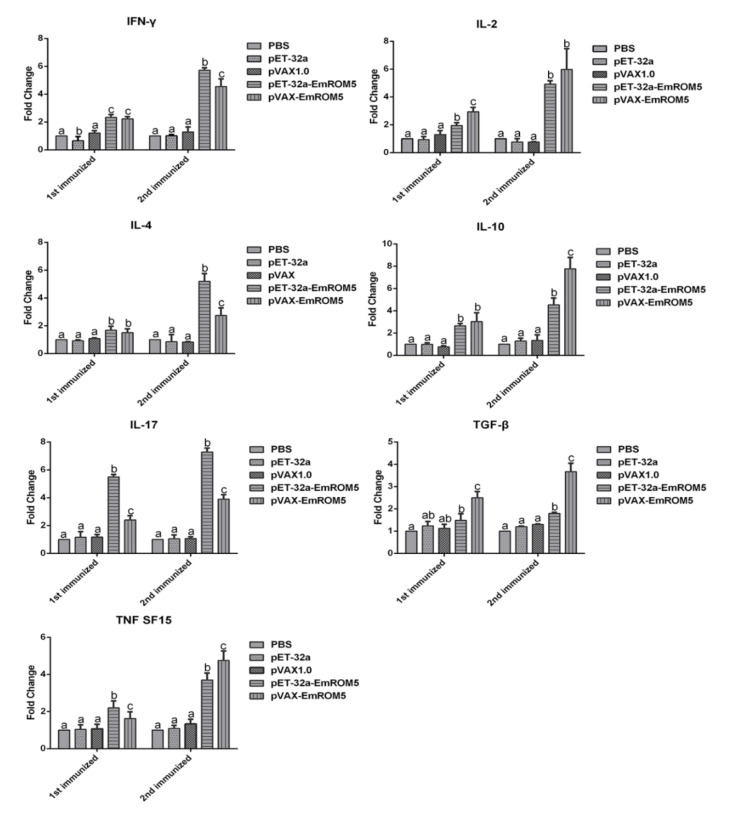

3.5. Changes of Cytokines Transcription in Splenic Lymphocytes in the EmROM5 Immunized Chickens

Changes in splenic lymphocyte cytokines that were induced by EmROM5 were detected by qPCR. The relative changes in the mRNA transcription levels of seven cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, TNF SF15, TGF-β, and IL-10, in the splenic lymphocytes are shown in Figure 4. In the pET-32a–EmROM5 recombinant protein (rEmROM5) immunization group, the mRNA levels of all of the above cytokines, except TGF-β, were significantly increased compared to those in the PBS and pET-32a tag protein groups seven days after the first immunization (p < 0.05), while the mRNA levels of all seven of the cytokines increased significantly seven days after the second immunization (p < 0.05). In the pVAX–EmROM5 immunization group, the mRNA levels of the seven cytokines increased significantly compared to in the PBS and pVAX 1.0 groups seven days after the first and second immunization (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Changes in mRNA transcription of cytokines in splenic lymphocytes following the immunization of rEmROM5 and pVAX-EmROM5 (n = 5, value = mean ± SD). Significant difference (p < 0.05) between numbers with different letters, and no significant difference (p > 0.05) between numbers with the same letter.

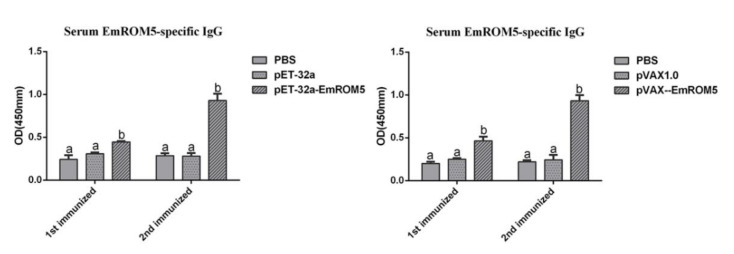

3.6. Specific Antibody IgG Levels in Chicken Serum after Immunization

The levels of the specific antibody IgG in the serum from the chickens who had been immunized with rEmROM5 and pVAX–EmROM5 were detected by indirect ELISA (Figure 5). Compared to the three control groups, the levels of specific antibody IgG in the two immunized groups were significantly increased one week after the first and second immunization (p < 0.05) period. Furthermore, the antibody level one week after the second immunization was higher than that after the first immunization. No significant differences were observed between the PBS and pET-32a tag protein or pVAX1.0 groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Serum EmROM5-specific IgG levels after immunization with rEmROM5 and pVAX–EmROM5 (n = 5, value = mean ± SD). Significant difference (p < 0.05) between numbers with different letters, and no significant difference (p > 0.05) between numbers with the same letter.

3.7. Protective Efficacy of EmROM5 against Challenge with E. maxima

Two vaccination challenge trials were performed to assess the protective efficacies of rEmROM5 and pVAX–EmROM5 against the challenge of E. maxima. The results are shown in Table 3. Compared to the unchallenged control groups in trial 1 and trial 2, the average weight gains in the four challenged control groups (the pET-32a tag protein and pVAX1.0 control groups were challenged groups in trial 1 and trial 2) were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Compared to the four challenged control groups, immunization with rEmROM5 or pVAX–EmROM5 significantly increased weight gain in the immunized chickens (p < 0.05). Moreover, the average OPG and enteric lesions of the rEmROM5- and pVAX–EmROM5-immunized chickens were significantly lower than those of the four challenged control groups (p < 0.05); the ACI of the immunized chickens were above 160, which indicated that the recombinant protein and plasmid provided moderate protective efficacy against E. maxima infection in chickens.

4. Discussion

Coccidiosis is a highly infectious parasitic disease and causes great losses to the world poultry industry [32]. In the current strategies for controlling chicken coccidiosis, anticoccidial drugs have the disadvantages of drug resistance and drug residue, and traditional live vaccines also create safety and cost problems. Hence, genetically engineering vaccines, including subunit vaccines and DNA vaccines, has been considered to be a prospective alternative measure against coccidiosis [14,33,34,35,36]. E. maxima is one of the most prevalent species that cause coccidiosis in clinics; however, there are limited reports on new vaccine antigens against E. maxima. To find a new vaccine antigen, it is essential to study its immune protection. Several studies have reported evaluations of the immune protective effect of E. maxima antigens; for example, EmMIC2 and gametocyte antigen Gam82 of E. maxima both have good immune effects against E. maxima infection in chickens and can be in the development of new vaccines [37,38]. Our study evaluated the immunogenicity and protective effect of EmROM5 and found that EmROM5 induced significant immune responses and produced moderate protection against E. maxima challenge. Our study enriches the candidate antigens for the development of new types of vaccines against E. maxima.

In apicomplexan protozoa, invasion-related molecules are always considered to be potential candidate antigens for the development of new vaccines and show promising protection levels against protozoa infection. For example, in Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum, apical membrane antigen 1(AMA1) binds to its receptor rhoptry neck 2(RON2); their interaction promotes the invasion of protozoa into the host cell [39]. Various animal protection experiments have proven that AMA1 has developed as an effective candidate vaccine antigen against many apicomplexan protozoa [40,41]. In coccidiosis vaccine research, microneme proteins (MICs) are considered to be ideal protective antigens. MICs are secreted by microneme to the surface of the parasite cell membrane, which can recognize and bind with the specific ligands on the host cell surface and can play key roles in the attachment and invasion of the Eimeria sporozoite [42]. The protective efficacy of the MICs of various Eimeria (EtMIC1, EtMIC2, EaMIC2, EmMIC2, EmiMIC3) has been evaluated by means of homogenous challenge animal experiments, and the results revealed that the MICs provided promising protection against Eimeria infection [37,43,44,45,46]. Similarly, ROMs are also important invasion associated antigens, they can cleave MICs in the transmembrane region, cut off the connection between MICs and the host cell ligand at the late stages of invasion, and finally, can cause the parasite to enter the cell completely [47,48]. Some reports on protozoan ROMs have studied the immune protection of ROMs. In T. gondii, Li and Zhang et al. determined the immune effect of pVAX–TgROM1, pVAX–TgROM4, and pVAX–TgROM5; they found that these TgROMs provided partial immune protection against T. gondii infection in mice [20,21]. In studies of the E. tenella rhomboid-like protein, Yang et al. constructed a recombinant fowlpox virus (rFPV) that could express the rhomboid gene of E. tenella, and Li et al. expressed its recombinant protein in E. coli. Both forms produced good immune protection against homologous challenge [18,19]. In this study, we found that EmROM5 provided moderate protective efficacy against E. maxima infection, which perhaps demonstrated that EmROM5 plays a certain role in the invasion of E. maxima from the other side. Nevertheless, this deduction requires further verification via specific experiments in the future.

Good immunogenicity is not only a necessary characteristic of a candidate antigen, but it is also a prerequisite for the vaccine to play an immune protective role. The immune response of chickens against coccidiosis is mainly mediated by cellular immunity involving T lymphocytes [49]. CD8+ T cells increase in number and play a major role in the secondary infection of parasites [50]; some studies have reported that CD8+ T cells come into direct contact with intestinal epithelial cells that have been invaded by parasites to destroy the infected cells [49,51]. CD4+ T cells increase significantly after primary infection and secrete a variety of cytokines that regulate cellular and humoral immunity [50]. Although the role of the humoral immune response in chicken infection with coccidia is controversial [49,50], some studies have shown that it has a certain relationship with immune protection. Parasite-reactive serum IgG is usually detected within 1 week after the oral infection of Eimeria oocysts [52]. The specific antibody can be transmitted to the filial generation through egg yolk and prevents Eimeria infection for a long time [53,54]. In this study, we determined the immunogenicity of EmROM5 in the form of a subunit vaccine and DNA vaccine by detecting the cellular immune response (T lymphocyte subpopulation, and cytokine level) and humoral immune response (specific IgG level). We found that in vaccinated chickens, immunization with EmROM5 increased the CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte proportions in the spleens as well as the levels of the mRNA levels of six cytokines and the level of the serum-specific IgG. These results suggest that EmROM5 induced robust cellular and humoral immune responses in the immunized chickens, showing good immunogenicity.

It is worth mentioning that many cytokines play important and complex roles in anticoccidial immunity [55]. After Eimeria infection, the T lymphocytes in chickens can secrete a variety of cytokines, such as Th1-type (IFN-γ and IL-2), Th2-type (IL-4), and Th17-type (IL-17) cytokines; regulatory cytokines (TGF-β and IL-10); TNF, and so on [56,57]. Th1-type cytokines play major roles against Eimeria infection [32,57]. IFN-γ is a core cytokine that plays an anticoccidial role by mediating Th1 cell response, and it can inhibit the intracellular development of Eimeria. IL-2 can promote the growth and differentiation of many immune cells, such as T, B, NK cells [56,57]. In our results, the mRNA levels of both cytokines increased, indicating the strong activation of anticoccidial immunity in the immunized chickens. In addition, IL-4 can regulate humoral immunity and can promote B cell development and antibody production [58]. The mRNA level of IL-4 and the specific serum IgG level that we determined increased consistently, a finding that is consistent with what has been described in the literature. They both indicate that humoral immunity plays a certain role in resisting Eimeria infection. Moreover, the up-regulation of IL-17 and TNF after Eimeria infection can promote the production of pro-inflammatory response. They cooperate with other cytokines to play roles that are involved in both anti-infection and in the killing of invasive parasites [32,57,59,60]. Generally, the immune response of the body is a two-way regulation process. There are anti-inflammatory cytokines that are secreted by Treg cells. TGF-β is an inhibitory cytokine with immunomodulatory functions. It promotes the repair of the damaged intestinal epithelium and inhibits the proliferation of T and B cells [32,61]. IL-10 can inhibit the occurrence of host self-injury and can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [62]. The production of these two inhibitory cytokines is also essential for immune protection against coccidiosis.

Lastly, although the DNA vaccine and subunit vaccine of EmROM5 only demonstrated moderate protective effects against E. maxima, there are additional measures that can be used to improve the protective efficacy of these vaccines. Some cytokines can be used as immune adjuvants to enhance the effects of the vaccines. The protective effect of the DNA vaccine can be strengthened by co-immunization with plasmids containing the cytokine genes of IL-8, IFN-γ, IL-15, or IL-1β [63]. Additionally, antigen and cytokine genes such as IL-2, IL-15, IFN-γ were combined into a plasmid for expression to enhance immune response [64,65]. In the case of the combined injection of Freund’s adjuvant and the ISA 71 VG adjuvant, the protective effect of the subunit vaccine was improved [66,67]. In addition, in order to improve the vaccine effect, we can also optimize the immunization procedure in terms of the dose, route of vaccination, vaccination age, and interval time, etc. [68]. Therefore, the application of EmROM5 as a candidate antigen in DNA vaccines and in subunit vaccines in broiler production requires further research in order to obtain the best immune effect.

5. Conclusions

The E. maxima ROM5 can significantly induce cellular and humoral immune responses and can provide moderate protection against E. maxima infection. All of the results demonstrated that EmROM5 is a promising candidate antigen for DNA vaccine and subunit vaccine development against clinical chicken coccidia infection.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/vaccines10010032/s1, Figure S1: The original image for Lane 1 in Figure 2C in the main article, Figure S2: The original image for Lane 2 in Figure 2C in the main article, Figure S3: The original image for Lane 3 in Figure 2C in the main article, Figure S4: The original image for Lane 1 in Figure 3B in the main article, Figure S5: The original image for Lane 2 in Figure 3B in the main article.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.S., R.Y., L.X. and X.L. (Xiangrui Li); validation, D.T.; formal analysis, D.T. and X.S.; data curation, D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. (Xiaoqian Liu) and D.T.; writing—review and editing, X.L. (Xiaoqian Liu), D.T. and X.S.; project administration, X.S., R.Y., L.X. and X.L. (Xiangrui Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31972705, 31672545), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (Grant No. BK 20161442), and Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were carried out follow the review and approval of the Committee on Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics of Nanjing Agricultural University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lillehoj H.S., Ruff M.D., Bacon L.D., Lamont S.J., Jeffers T.K. Genetic control of immunity to Eimeria tenella. Interaction of MHC genes and non-MHC linked genes influences levels of disease susceptibility in chickens. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1989;20:135–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song X.K., Gao Y.L., Xu L.X., Yan R.F., Li X.R. Partial protection against four species of chicken coccidia induced by multivalent subunit vaccine. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;212:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake D.P., Knox J., Dehaeck B., Huntington B., Rathinam T., Ravipati V., Ayoade S., Gilbert W., Adebambo A.O., Jatau I.D., et al. Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Vet. Res. 2020;51:115. doi: 10.1186/s13567-020-00837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lan L.H., Sun B.B., Zuo B.X.Z., Chen X.Q., Du A.F. Prevalence and drug resistance of avian Eimeria species in broiler chicken farms of Zhejiang province, China. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:2104–2109. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams R.B., Bushell A.C., Reperant J.M., Doy T.G., Morgan J.H., Shirley M.W., Yvore P., Carr M.M., Fremont Y. A survey of Eimeria species in commercially-reared chickens in France during 1994. Avian Pathol. 1996;25:113–130. doi: 10.1080/03079459608419125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamal G., Zivar S.D., Mohammadali B. Prevalence of coccidiosis in broiler chicken farms in Western Iran. J. Vet. Med. 2014;2014:980604. doi: 10.1155/2014/980604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y.Y., Ruan X.C., Li L., Zeng M.H. Prevalence of Eimeria species in domestic chickens in Anhui province, China. J. Parasit. Dis. 2017;41:1014–1019. doi: 10.1007/s12639-017-0927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X.M., Pang W., Jia T., Yan W.C., He G., Hao L.L., Bentué M., Suo X. Prevalence of Eimeria species in broilers with subclinical signs from fifty farms. Avian Dis. 2009;53:301–305. doi: 10.1637/8379-061708-Resnote.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godwin R.M., Morgan J.A.T. A molecular survey of Eimeria in chickens across Australia. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;214:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moraes J.C., França M., Sartor A.A., Bellato V., de Moura A.B., de Lourdes Borba Magalhães M., de Souza A.P., Miletti L.C. Prevalence of Eimeria spp. in broilers by multiplex PCR in the southern region of Brazil on two hundred and fifty farms. Avian Dis. 2015;59:277–281. doi: 10.1637/10989-112014-Reg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R.B. Anticoccidial vaccines for broiler chickens: Pathways to success. Avian Pathol. 2002;31:317–353. doi: 10.1080/03079450220148988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen P.C., Fetterer R.H. Recent advances in biology and immunobiology of Eimeria species and in diagnosis and control of infection with these coccidian parasites of poultry. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:58–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.58-65.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman H.D. Resistance to anticoccidial drugs in fowl. Parasitol. Today. 1993;9:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad T.A., El-Sayed B.A., El-Sayed L.H. Development of immunization trials against Eimeria spp. Trials Vaccinol. 2016;5:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.trivac.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos J.M., Graindorge A., Soldati-favre D. New insights into parasite rhomboid proteases. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2012;182:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brossier F., Starnes G.L., Beatty W.L., Sibley L.D. Microneme rhomboid protease TgROM1 is required for efficient intracellular growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:664–674. doi: 10.1128/EC.00331-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng J., Gong P.T., Jia H.L., Li M.Y., Zhang G.C., Zhang X.C., Li J.H. Eimeria tenella rhomboid 3 has a potential role in microneme protein cleavage. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;201:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang G.L., Li J.H., Zhang X.C., Zhao Q., Liu Q., Gong P.T. Eimeria tenella: Construction of a recombinant fowlpox virus expressing rhomboid gene and its protective efficacy against homologous infection. Exp. Parasitol. 2008;119:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J.H., Zheng J., Gong P.T., Zhang X.C. Efficacy of Eimeria tenella rhomboid-like protein as a subunit vaccine in protective immunity against homologous challenge. Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:1139–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J.H., Han Q.Z., Gong P.T., Yang T., Ren B.Y., Li S.J., Zhang X.C. Toxoplasma gondii rhomboid protein 1 (TgROM1) is a potential vaccine candidate against toxoplasmosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;184:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang N.Z., Xu Y., Wang M., Petersen E., Chen J., Huang S.Y., Zhu X.Q. Protective efficacy of two novel DNA vaccines expressing Toxoplasma gondii rhomboid 4 and rhomboid 5 proteins against acute and chronic toxoplasmosis in mice. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2015;14:1289–1297. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1061938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomley F. Techniques for isolation and characterization of apical organelles from Eimeria tenella sporozoites. Methods. 1997;13:171–176. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song H.Y., Yan R.F., Xu L.X., Song X.K., Shah M.A., Zhu H.L., Li X.R. Efficacy of DNA vaccines carrying Eimeria acervulina lactate dehydrogenase antigen gene against coccidiosis. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;126:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez H., Chapot R., Banzet S., Koulmann N., Birot O., Bigard A.X., Peinnequin A. Quantification by real-time PCR of developmental and adult myosin mRNA in rat muscles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;340:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenneth J.L., Thomas D.S. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song X.K., Zhao X.F., Xu L.X., Yan R.F., Li X.R. Immune protection duration and efficacy stability of DNA vaccine encoding Eimeria tenella TA4 and chicken IL-2 against coccidiosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017;111:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holdsworth P.A., Conway D.P., McKenzie M.E., Dayton A.D., Chapman H.D., Mathis G.F., Skinner J.T., Mundt H.C., Williams R.B., World association for the advancement of veterinary parasitology World association for the advancement of veterinary parasitology (WAAVP) guidelines for evaluating the efficacy of anticoccidial drugs in chickens and turkeys. Vet. Parasitol. 2004;121:189–212. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson J., Reid W.M. Anticoccidial drugs: Lesion scoring techniques in battery and floor-pen experiments with chickens. Exp. Parasitol. 1970;28:30–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(70)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose M.E., Mockett A.P. Antibodies to coccidia: Detection by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Parasite Immunol. 1983;5:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1983.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talebi A., Mulcahy G. Partial protection against Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria tenella induced by synthetic peptide vaccine. Exp. Parasitol. 2005;110:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mcmanus E.C., Campbell W.C., Cuckler A.C. Development of resistance to quinoline coccidiostats under field and laboratory conditions. J. Parasitol. 1968;54:1190–1193. doi: 10.2307/3276989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalloul R.A., Lillehoj H.S. Poultry coccidiosis: Recent advancements in control measures and vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2006;5:143–163. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivory C., Chadee K. DNA vaccines: Designing strategies against parasitic infections. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2004;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blake D.P., Tomley F.M. Securing poultry production from the ever-present Eimeria challenge. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song X.K., Ren Z., Yan R.F., Xu L.X., Li X.R. Induction of protective immunity against Eimeria tenella, Eimeria necatrix, Eimeria maxima and Eimeria acervulina infections using multivalent epitope DNA vaccines. Vaccine. 2015;33:2764–2770. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meunier M., Chemaly M., Dory D. DNA vaccination of poultry: The current status in 2015. Vaccine. 2016;34:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J.W., Zhang Z.C., Li M.H., Song X.K., Yan R.F., Xu L.X., Li X.R. Eimeria maxima microneme protein 2 delivered as DNA vaccine and recombinant protein induces immunity against experimental homogenous challenge. Parasitol. Int. 2015;64:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang S.I., Lillehoj H.S., Lee S.H., Lee K.W., Park M.S., Cha S.R., Lillehoj E.P., Subramanian B.M., Sriraman R., Srinivasan V.A. Eimeria maxima recombinant Gam82 gametocyte antigen vaccine protects against coccidiosis and augments humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Vaccine. 2010;28:2980–2985. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamarque M., Besteiro S., Papoin J., Roques M., Vulliez-Le Normand B., Morlon-Guyot J., Dubremetz J.F., Fauquenoy S., Tomavo S., Faber B.W., et al. The RON2-AMA1 interaction is a critical step in moving junction-dependent invasion by apicomplexan parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001276. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia L.J., Guo H.P., Liu M.M., Gao Y., Zhang L., Li H., Xie S.Z., Zhang N.N. Construction of an adenovirus vaccine expressing the cross-reactive antigen AMA1 for Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii and its immune response in an animal model. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2018;13:235–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remarque E.J., Faber B.W., Kocken C.H., Thomas A.W. Apical membrane antigen 1: A malaria vaccine candidate in review. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomley F.M., Soldati D.S. Mix and match modules: Structure and function of microneme proteins in apicomplexan parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01761-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi N.S., Wang Y.Y., Liao S.Q., Wu C.Y., Lv M.N., Li J., Tong Z.X., Sun M.F. Partial protective of chickens against Eimeria tenella challenge with recombinant EtMIC-1 antigen. Parasitol. Res. 2013;112:2281–2287. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan M.Y., Cui X.X., Zhao Q.P., Zhu S.H., Huang B., Wang L., Zhao H.Z., Liu G.L., Li Z.H., Han H.Y., et al. Molecular characterization and protective efficacy of the microneme 2 protein from Eimeria tenella. Parasite. 2018;25:60. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2018061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z.C., Liu L.R., Huang J.W., Wang S., Lu M.M., Song X.K., Xu L.X., Yan R.F., Li X.R. The molecular characterization and immune protection of microneme 2 of Eimeria acervulina. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;215:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang X.M., Liu J.H., Tian D., Li W.Y., Zhou Z.Y., Huang J.M., Song X.K., Xu L.X., Yan R.F., Li X.R. The molecular characterization and protective efficacy of microneme 3 of Eimeria mitis in chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2018;258:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dowse T.J., Pascall J.C., Brown K.D., Soldati D. Apicomplexan rhomboids have a potential role in microneme protein cleavage during host cell invasion. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005;35:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ha Y. Structure and mechanism of intramembrane protease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lillehoj H.S., Trout J.M. Avian gut-associated lymphoid tissues and intestinal immune responses to Eimeria parasites. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;9:349–360. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yun C.H., Lillehoj H.S., Lillehoj E.P. Intestinal immune responses to coccidiosis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2000;24:303–324. doi: 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lillehoj H.S., Lillehoj E.P. Avian coccidiosis. A review of acquired intestinal immunity and vaccination strategies. Avian Dis. 2000;44:408–425. doi: 10.2307/1592556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lillehoj H.S., Ruff M.D. Comparison of disease susceptibility and subclass-specific antibody response in SC and FP chickens experimentally inoculated with Eimeria tenella, E. acervulina, or E. maxima. Avian Dis. 1987;31:112–119. doi: 10.2307/1590782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallach M., Halabi A., Pillemer G., Sar-Shalom O., Mencher D., Gilad M., Bendheim U., Danforth H.D., Augustine P.C. Maternal immunization with gametocyte antigens as a means of providing protective immunity against Eimeria maxima in chickens. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:2036–2039. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2036-2039.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Witcombe D.M., Smith N.C. Strategies for anticoccidial prophylaxis. Parasitology. 2014;141:1379–1389. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapman H.D. Milestones in avian coccidiosis research: A review. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:501–511. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lillehoj H.S., Min W., Dalloul R.A. Recent progress on the cytokine regulation of intestinal immune responses to Eimeria. Poult. Sci. 2004;83:611–623. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim W.H., Chaudhari A.A., Lillehoj H.S. Involvement of T cell immunity in avian coccidiosis. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2732. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Annamalai T., Selvaraj R.K. Effects of in ovo interleukin-4-plasmid injection on anticoccidia immune response in a coccidia infection model of chickens. Poult. Sci. 2012;91:1326–1334. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Min W., Kim W.H., Lillehoj E.P., Lillehoj H.S. Recent progress in host immunity to avian coccidiosis: IL-17 family cytokines as sentinels of the intestinal mucosa. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2013;41:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang S., Lillehoj H.S., Ruff M.D. Chicken tumor necrosis-like factor.: 1. in vitro production by macrophages stimulated with Eimeria tenella or bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Poult. Sci. 1995;74:1304–1310. doi: 10.3382/ps.0741304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jakowlew S.B., Mathias A., Lillehoj H.S. Transforming growth factor-beta isoforms in the developing chicken intestine and spleen: Increase in transforming growth factor-beta 4 with coccidia infection. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1997;55:321–339. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(96)05628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arendt M.K., Sand J.M., Marcone T.M., Cook M.E. Interleukin-10 neutralizing antibody for detection of intestinal luminal levels and as a dietary additive in Eimeria challenged broiler chicks. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:430–438. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Min W., Lillehoj H.S., Burnside J., Weining K.C., Staeheli P., Zhu J.J. Adjuvant effects of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, IL-15, IFN-α, IFN-γ, TGF-β4 and lymphotactin on DNA vaccination against Eimeria acervulina. Vaccine. 2001;20:267–274. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lillehoj H.S., Ding X.C., Quiroz M.A., Bevensee E., Lillehoj E.P. Resistance to intestinal coccidiosis following DNA immunization with the cloned 3-1E Eimeria gene plus IL-2, IL-15, and IFN-gamma. Avian Dis. 2005;49:112–117. doi: 10.1637/7249-073004R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song X.K., Huang X.M., Yan R.F., Xu L.X., Li X.R. Efficacy of chimeric DNA vaccines encoding Eimeria tenella 5401 and chicken IFN-γ or IL-2 against coccidiosis in chickens. Exp. Parasitol. 2015;156:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wallach M., Smith N.C., Petracca M., Miller C.M., Eckert J., Braun R. Eimeria maxima gametocyte antigens: Potential use in a subunit maternal vaccine against coccidiosis in chickens. Vaccine. 1995;13:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)98255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang S.I., Lillehoj H.S., Lee S.H., Lee K.W., Lillehoj E.P., Bertrand F., Dupuis L., Deville S. Montanide IMS 1313 N VG PR nanoparticle adjuvant enhances antigen-specific immune responses to profilin following mucosal vaccination against Eimeria acervulina. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;182:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song X.K., Xu L.X., Yan R.F., Huang X.M., Shah M.A., Li X.R. The optimal immunization procedure of DNA vaccine pcDNA-TA4-IL-2 of Eimeria tenella and its cross-immunity to Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria acervulina. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;159:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials.