Abstract

Background

The use of modern contraceptives (MC) in most African countries has been low despite the high fertility rate and unmet need for family planning. This study sought to determine the coverage and determinants of modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Methods

Data for the study were obtained from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted between 1995–2020 across 37 SSA countries. Women of reproductive age (15–49 years) was the unit of analysis. Analysis of data was done using STATA version 16 for windows. A bivariate Rao Scott’s Chi-square test of independence was done to determine factors associated with the use of modern contraceptives. Factors that showed significance (p < 0.05) were included in a multilevel logistic regression to determine significant predictors of modern contraceptives. Clustering, stratification and sample weighting were accounted for in the analyses.

Results

The overall prevalence of the use of MC was found to be 22.0%. This ranged from 3.5% in the Central Africa Republic to 49.7% in Namibia. The most common type of MC used were injections (39.4%), condoms (17.5%) and implants (26.5%). Women were less likely to use modern contraceptive if they: had no education (aOR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.38–0.44), had no children (aOR = 0.27–0.42), not told of family planning at a health facility (aOR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.67–0.71), not heard of family planning in the media (aOR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.74–0.79) and being poor (aOR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.73–0.79). On the other hand, women were more likely to use modern contraceptive if they were between the age of 35–39 years (aOR = 1.69, 95% CI 0.73–0.79), married (aOR = 2.66, 95% CI 2.50–2.83), had seven or more children (aOR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.17–0.38), had knowledge of any method of contraceptives (aOR = 303.8, 95% CI 89.9–1027.5) and when field worker visited and talked about family planning (aOR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.39–0.68).

Conclusion

The study showed a low prevalence of modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Findings from the study highlight the need to provide education to women to increase uptake of modern contraceptive and also re-enforce contraceptive interventions to improve women’s health and well-being.

Keywords: Contraceptive, Determinants, Coverage, Sub-Saharan Africa

Plain Language summary

The use of modern contraceptives (MC) to protect against sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancy and mortality as a result of unsafe abortion is low in many African countries. This study sought to determine the coverage and factors associated with the use of MC among women of child-bearing age in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Data for the study were obtained from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 37 SSA countries. Interpretation of the data focussed on women of children bearing age (15–49 years). The overall prevalence of the use of MC was found to be 22.0%. This ranged from 3.5% in the Central Africa Republic to 49.7% in Namibia. The most common type of MC used were injections (39.4%), condoms (17.5%) and implants (26.5%). Women were less likely to use MC if they had no education, no children, were not told of family planning at a health facility, had not heard of family planning on the Television, radio, newspaper and were poor. On the other hand, women who were between 35–39 years, were married, had seven or more children, had knowledge of any method of contraceptives and had a field worker visited and talked about family planning were more likely to use modern contraceptives. The study showed a low prevalence of MC use in sub-Saharan Africa. The results from the study is important and emphasize the need to provide education to women of child-bearing age to increase uptake of MC to reduce mortality and improve on women’s health and well-being.

Background

Among the targets (3.7) in goal 3 of the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) is to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs [1]. Family planning (FP) has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a voluntary and informed decision by an individual or couple on the number of children to have and when to have them [2]. It is characterized by the use of contraceptives, either modern or traditional methods. Modern contraceptive methods include male and female sterilization, male and female condoms, depot implants, pills, Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM), Intra-Uterine Devices (IUD), and emergency contraception [2]. On the other hand, traditional methods comprise the withdrawal and rhyme method (periodic abstinence) [3]. Of these two methods, modern contraceptive (contraceptive) has been recognized as an effective method for fertility reduction, and are being widely promoted to slow rapid population growth, particularly in developing countries [4, 5].

The use of MC has several benefits. These include birth spacing, reduce unwanted or unintended pregnancies, prevent unsafe abortions, improves maternal health, reduce infant mortality, and prevents sexually transmitted diseases [6]. Identified non-health benefits include expanded education opportunities and empowerment for women, poverty reduction, and ensure sustainable population growth and economic development for countries [7]. It is, therefore, necessary that information on the use of MC is made readily available and accessible to accelerate national efforts of achieving health goals.

Despite these established benefits of family planning, the use of MC is low especially in sub-Saharan Africa countries [3]. Globally, among the 1.9 billion women of reproductive age group (15–49 years) in 2019, 1.1 billion have a need for family planning; of these, 842 million are using contraceptive methods, and 270 million have an unmet need for contraception [2]. Using countries in the family planning 2020 (FP2020) initiative, the average prevalence of modern contraceptive use was estimated to be 23.9% and 28.5% among married women and those engaged in relationships between 2012 and 2017 respectively [3].

In 2012 and 2017 the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married women or those in relationships in Africa was reported to be low: estimated at 23.9% and 28.5% respectively [3]. In a recent large population-based study to estimate the prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 20 African countries, Ayampa et al. [8] reported a 26% prevalence of modern contraceptive use with a country-specific variation of 6% in Guinea to 62% in Zimbabwe.

The factors that influence contraceptive practice are multidimensional and have been reported to range from knowledge of contraceptives methods, socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, religion, level of income, marital status, employment), parity, number of living children, source of reproductive information, frequency of antenatal visits, terminated pregnancy, prior HIV testing, residence (rural or urban), literacy, being sexually active, partners communication and approval and fear of side effects of contraceptives [9–16].

Earlier studies on modern contraceptive use in Africa have focused on individual countries [9–11, 13, 17–19]. Very few studies have assessed the prevalence and use of MC across Africa [8, 20–22]. This paucity of information was the drive to this study on the holistic assessment of the prevalence and determinants of modern contraceptive use in the sub-Saharan African region. The study therefore aimed at assessing the coverage and determinants of modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) using the available latest demographic and health survey data of sub-Saharan African countries. Findings for this study are important in the global and local context, particularly within the African region to improve maternal and child health outcomes.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study.

Data source, sampling design and study population

In this study, secondary data of demographic and health survey (DHS) of sub-Saharan Africa countries were used. DHS is a nationally representative household sample survey that evaluates population socio-demographics, maternal and child health, and a variety of health indicators including the use of contraceptives. The DHS is a valuable source of data for studying population health indicators because of its coverage, data quality, and comparability throughout the world. In addition, the sample used is generally representative at the national, regional, and residence (rural and urban) level. DHS sampling is based on a two-stage cluster design approach. In the first stage, there is stratification and proportional allocation of the sample frame. The second stage involves a selection of households per cluster with equal probabilities in a systematic approach. Details of the sampling design and sampling procedure can be found at the DHS program websites (www.dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey-types/DHS).

The available latest demographic and health survey (DHS) conducted in 37 sub-Saharan Africa countries from 1995 to 2020 were included in this study. These countries include Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Comoros, Congo, Congo Democratic, Cote d'Ivoire, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principle, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and, Zimbabwe. Data were downloaded from the DHS programme website (www.dhsprogram.com) after granting permission. The data archive at the DHS website had 38 sub-Saharan Africa countries excluding Ondo State in Nigeria. Chad was not included because of its extremely old data (1990) and was missing most of the independent variables of interest as well as lack of stratification. The unit of analysis in this study was women of reproductive age (15–49 years).

Definition of variables

Outcome variable

The current use of MC by women of reproductive age (15–49 years) was the primary outcome of interest. This was dichotomized as “use of a modern method (coded as “1”) and non-use of modern contraceptive (coded as “0”). Modern contraceptive was described as the use of any of the following contraceptive methods: sterilization (female), intrauterine system (IUD), injectable, implant, tablets, condom (female), standard days method (SDM), emergency contraception, diaphragm, foam/jelly, diaphragm, country-specific modern methods, and other modern contraceptive methods respondent mentioned (including cervical cap, contraceptive sponge, and others) but does not include abortion, menstrual regulation as described in the DHS questionnaire. Traditional methods included periodic abstinence (rhythm, calendar method), withdrawal (coitus interruptus) and country-specific traditional methods of proven effectiveness, and folk methods including locally described methods and/or spiritual methods such as herbs, amulets, gris-gris, etc.

Independent variables

The independent variables considered in this study include socio-demographic characteristics such as the age of the respondent (“15–19”, “20–24, 25–29”, “30–34”, “35–39”, “40–44” and “45–49”), age at first birth, recoded (“no birth”, “< 20”, “20–29” and 29+), education (“no education”, “Primary”, “secondary” and “higher”), husband/partners education (“no education”, “Primary”, “secondary” and “higher” “don’t know”) religion, recoded (“Christian”, “Islamic”, “Traditional” and “Other”), marital status, recoded (“Never married” “Married”, “Co-habiting” and “Other”), wealth index, recoded (“poorer/poorest”, “Middle” and “Richer/Richest”), Employment (“working” and “not working”). Others include the number of living children, recoded (“0”, “1–2”, “3–4”, “5–7” and “7+”), source of reproductive information, recoded as media (radio, television, newspaper, text messages, “Yes” and “No”), been told of family planning at a health facility (“Yes” and “No”), place of residence (“rural” or “urban”), the number of sex partners excluding the spouse, recoded (“none”, “1”, “2”, “3+” and “don’t know”) and knowledge of modern contraceptive (“Yes” and “No”), field worker visited and talked about family planning (“Yes” and “No”) and visited health facility in the last 12 months (“Yes” and “No”). These variables were chosen based on previous studies [8, 14, 16, 22].

Data analyses

Data for this study were analyzed using STATA version 16 for windows. Data were cross-checked for missing data and no response or interviewer error (9 or 99) and were excluded in the analyses. Again, missing data associated with the outcome variable, use of modern contraceptives, were dropped from the analyses. Descriptive statistics were summarised for demographic characteristics and prevalence of the use of MC in each country. A bivariate analysis (Rao Scott’s X2) was done to determine the association of socio-demographic characteristics, questions relating to the use of contraceptives, and the outcome variable (use of modern contraceptive). Variables that showed significance in the bivariate analysis were used for the multiple logistic regression analyses. The independent variables were checked for multi-colinearity before the multiple logistic regression. Sample weight was adjusted by dividing the individual women’s sample weight by 1000,000 (v005/106). In all analyses, clustering, stratification, and applied sampling weights were accounted for to reduce bias and to improve on the adjusted estimates and standard errors as recommended in complex survey design analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

This study required no ethical clearance as secondary data were used. However, written permission was sought and was granted from the DHS program before data access.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

The final sample size of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) for the 37 sub-Saharan Africa countries included in the analyses was 494,285. As of the time of this study, the countries with the latest DHS data were Liberia (2020), Senegal (2019), and Sierra Leone (2019). Central African Republic had the oldest DHS data (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Country specific sample size and survey year of the DHS

| Country | Year | Sample | % Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 2015–2016 | 14,379 | 2.9 |

| Benin | 2017–2018 | 15,928 | 3.2 |

| Burkina Faso | 2010 | 17,087 | 3.5 |

| Burundi | 2016–2017 | 17,269 | 3.5 |

| Cameroon | 2018 | 13,527 | 2.7 |

| Central African Republic | 1994–1995 | 5884 | 1.2 |

| Chad | 2014–2015 | 17,719 | 3.6 |

| Comoros | 2012 | 5329 | 1.1 |

| Congo | 2011–2012 | 10,819 | 2.2 |

| Congo Democratic Republic | 2013–2014 | 18,827 | 3.8 |

| Cote d'ivoire | 2011–2012 | 10,060 | 2.0 |

| Eswatini | 2006–2007 | 4987 | 1.0 |

| Ethiopia | 2016 | 15,683 | 3.2 |

| Gabon | 2012 | 8422 | 1.7 |

| Gambia | 2013 | 10,233 | 2.1 |

| Ghana | 2014 | 9396 | 1.9 |

| Guinea | 2018 | 10,874 | 2.2 |

| Kenya | 2014 | 31,079 | 6.3 |

| Lesotho | 2014 | 6621 | 1.3 |

| Liberia | 2019–2020 | 8065 | 1.6 |

| Madagascar | 2008–2009 | 17,375 | 3.5 |

| Malawi | 2015–2016 | 24,562 | 5.0 |

| Mali | 2018 | 10,519 | 2.1 |

| Mozambique | 2011 | 13,745 | 2.8 |

| Namibia | 2013 | 9176 | 1.9 |

| Niger | 2012 | 11,160 | 2.3 |

| Nigeria | 2018 | 41,821 | 8.5 |

| Rwanda | 2014–2015 | 13,497 | 2.7 |

| Sao Tome and Principle | 2008–2009 | 2615 | 0.5 |

| Senegal | 2019 | 8649 | 1.8 |

| Sierra Leone | 2019 | 15,574 | 3.2 |

| South Africa | 2016 | 8514 | 1.7 |

| Tanzania | 2015–2016 | 13,266 | 2.7 |

| Togo | 2013–2014 | 9480 | 1.9 |

| Uganda | 2016 | 18,506 | 3.7 |

| Zambia | 2018 | 13,683 | 2.8 |

| Zimbabwe | 2015 | 9955 | 2.0 |

| Total | 494,285 | 100.0 |

DHS Demographic and Health Survey

The mean age of the women was 28.5 ± 0.02 years (95% CI 28.5–28.6%) with 21.2% within the age of 15–19 years. About a third had their highest education in secondary (32.5%) and primary (32.2%). With respect to the educational level of their husbands/partners, 33.3, 27.8, 28.3, and 7.4% had no formal education, primary, secondary, and higher education. Most of the women (60.8%) resided in rural settings and were employed (60.0%). About half (50.9%) were married. With regards to wealth index, 35.9%, were poor/poorest and 44.9% were rich/richest. More than a quarter of the women had 1–2 (28.2%) and 3–4 (28.9%) living children. Women had heard of family planning on the media (42.6%) and had been told of family planning at a health facility (36.1%). Details of socio-demographic and sexual and reproductive characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and sexual and reproductive characteristics associated with the use of MC

| Variable | Weighted N | Weighted % | %Modern contraceptive use | Rao Scott’s X2 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group [28.5 ± 0.02, (28.5, 28.6)*] | ||||

| 15–19 | 104,795 | 21.2 | 9.0 | 1523.6 (< 0.01) |

| 20–24 | 91,263 | 18.5 | 23.9 | |

| 25–29 | 86,634 | 17.5 | 27.9 | |

| 30–34 | 71,274 | 14.4 | 28.9 | |

| 35–39 | 59,784 | 12.1 | 27.6 | |

| 40–44 | 44,301 | 9.0 | 23.8 | |

| 45–49 | 36,323 | 7.4 | 15.2 | |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| No education | 147,697 | 29.9 | 11.9 | 1439.4 (< 0.01) |

| Primary | 160,181 | 32.4 | 25.6 | |

| Secondary | 160,531 | 32.5 | 25.9 | |

| Higher | 25,925 | 5.24 | 32.1 | |

| Highest educational level of husband/partner | ||||

| No education | 107,539 | 33.3 | 12.7 | 1362.0 (< 0.01) |

| Primary | 89,945 | 27.8 | 29.9 | |

| Secondary | 91,573 | 28.3 | 29.4 | |

| Higher | 23,960 | 7.4 | 32.1 | |

| Don’t know | 10,198 | 3.2 | 18.9 | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 193,678 | 39.2 | 24.8 | 245.5 (< 0.01) |

| Rural | 300,696 | 60.8 | 20.1 | |

| Employment | ||||

| No | 190,888 | 40.0 | 18.6 | 510.2 (< 0.01) |

| Yes | 286,403 | 60.0 | 23.3 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 137,041 | 27.7 | 14.54 | 674.7 (< 0.01) |

| Married | 251,395 | 50.9 | 25.59 | |

| Co-habiting | 61,897 | 12.5 | 24.09 | |

| Other (widowed/divorced/no longer living with partner) | 44,038 | 8.9 | 21.32 | |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 289,346 | 64.6 | 25.8 | 1392.7 (< 0.01) |

| Islamic | 133,440 | 29.8 | 12.4 | |

| Traditional | 6984 | 1.6 | 9.4 | |

| Other | 18,079 | 4.0 | 18.1 | |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorer/poorest | 175,432 | 35.9 | 18.0 | 500.1 (< 0.01) |

| Middle | 93,856 | 19.2 | 22.2 | |

| Richer/Richest | 219,202 | 44.9 | 25.6 | |

| Number of living children | ||||

| None | 137,905 | 27.9 | 9.1 | 2334.6 (< 0.01) |

| 1–2 | 149,521 | 30.2 | 28.2 | |

| 3–4 | 110,897 | 22.4 | 28.9 | |

| 5–7 | 80,183 | 16.2 | 23.9 | |

| 7+ | 15,867 | 3.2 | 16.9 | |

| Told family planning at a health facility | ||||

| No | 158,281 | 63.9 | 34.0 | 567.2 (< 0.01) |

| Yes | 89,367 | 36.1 | 23.0 | |

| Number of sex partners excluding spouse | ||||

| None | 391,272 | 85.5 | 18.9 | 1088.8 (< 0.01) |

| 1 | 60,613 | 13.3 | 35.7 | |

| 2 | 5070 | 1.1 | 44.0 | |

| 3+ | 575 | 0.1 | 48.7 | |

| Don’t know | 46 | 0.01 | 59.2 | |

| Heard family planning on the media | ||||

| No | 283,556 | 57.4 | 17.4 | 4321.1 (p < 0.01) |

| Yes | 210,818 | 42.6 | 28.0 | |

| Age at first birth (19.3 ± 0.1)* | ||||

| No birth | 133,134 | 26.93 | 9.00 | 3019 (< 0.01) |

| < 20 | 215,240 | 43.54 | 26.22 | |

| 20–29 | 138,774 | 28.07 | 27.93 | |

| > 29 | 7225 | 1.46 | 19.07 | |

| Knowledge of modern method | ||||

| No | 30,815 | 7.2 | 0.01 | 9075.9 (< 0.01) |

| Yes | 463,558 | 92.8 | 23.42 | |

| Fieldworker visited and talked about family planning | ||||

| No | 19,861 | 53.0 | 11.3 | 309.8 (< 0.01) |

| Yes | 17,623 | 47.0 | 15.6 | |

| Visited health facility last 12 months | ||||

| No | 229,948 | 48.1 | 7.4 | 4342.4 (< 0.01) |

| Yes | 247,798 | 51.9 | 14.0 | |

*Mean ± Standard error

Prevalence of modern contraceptive use

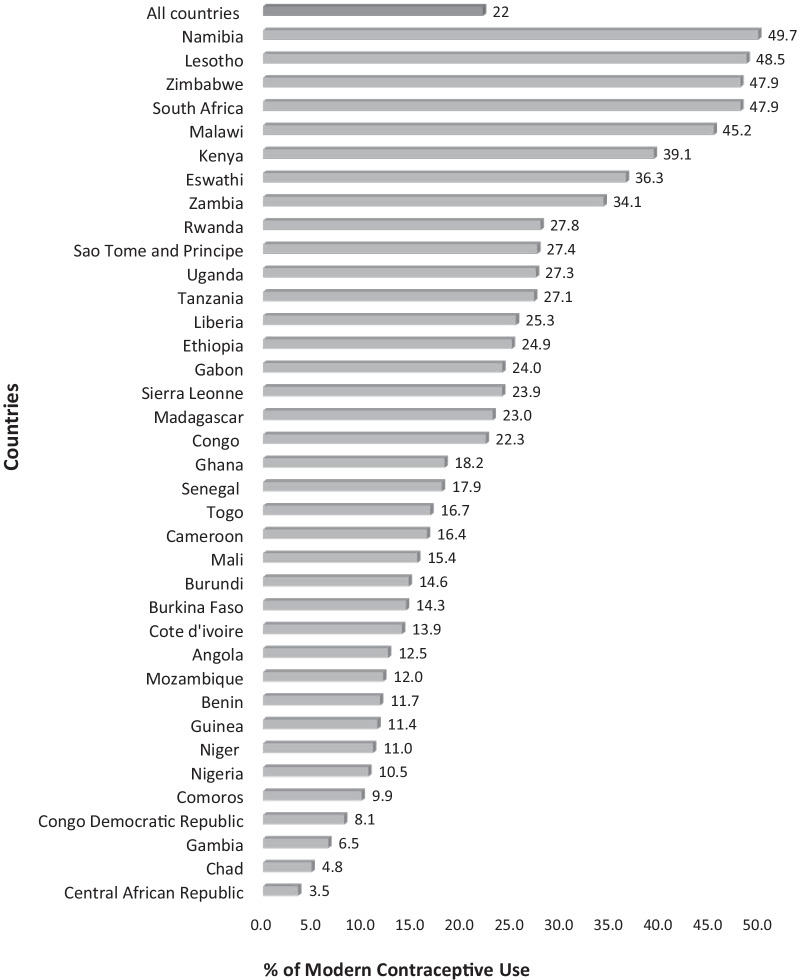

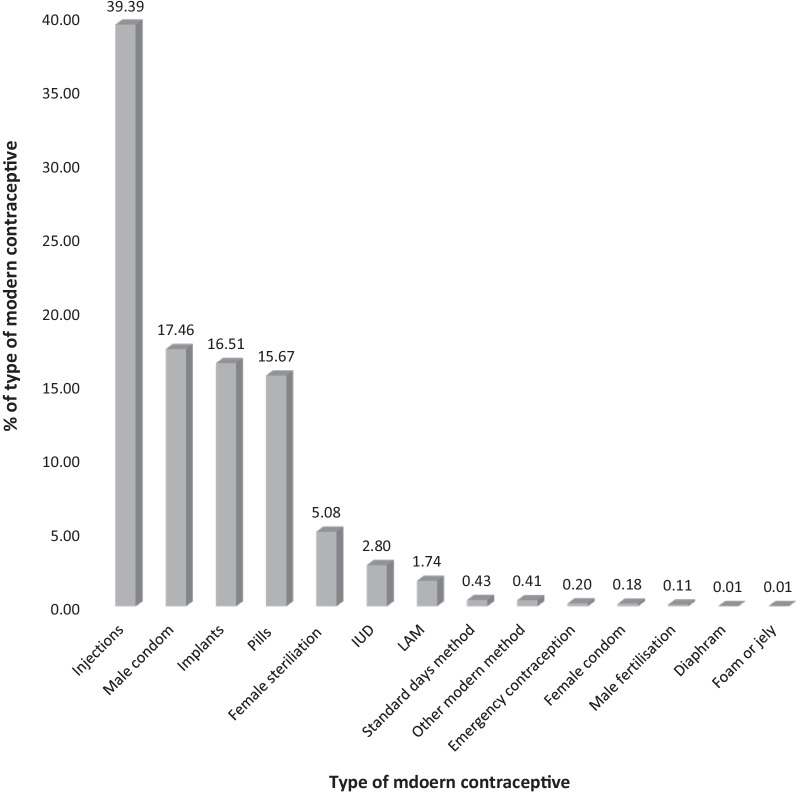

The pooled prevalence of modern contraceptive use was 22.0% (95% CI 21.8–22.2%). Coverage varied considerably across countries, ranging from the highest, 49.7% (95% CI 48.4–51.1%) in Namibia to lowest, 3.5% (95% CI 3.0–4.1%) in Central Africa Republic. Other countries that had high prevalence of MC use were Lesotho, 48.5% (95% CI 21.8–22.2%), Zimbabwe, 47.9% (95% CI 46.5–49.2%), South Africa, 47.9% (95% CI 46.2–49.5%), Malawi, 45.2% (95% CI 44.2–46.1%) and Kenya, 39.1% (95% CI 38.2–40.0%) (Fig. 1). The most commonly used family planning method (modern contraceptives) were injections (39.4%), male condoms (17.5%), implants (16.5%), and pills (15.7%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of MC use among women (15–49) years in sub-Saharan Africa. The pooled prevalence of modern contraceptive use was 22.0% (95% CI 21.8–22.2%). Coverage varied considerably across countries, ranging from the highest, 49.7% (95% CI 48.4–51.1%) in Namibia to lowest, 3.5% (95% CI 3.0–4.1%) in Central Africa Republic

Fig. 2.

Type of modern contraceptive used. The most commonly used family planning method (modern contraceptives) were injections (39.4%), male condoms (17.5%), implants (16.5%), and pills (15.7%)

Factors associated with modern contraceptive use

In a bivariate analysis (Rao Scott’s X2), all the socio-demographic characteristics used in the study (educational level, place of residence, religion, employment status, marital status, and wealth index), as well as the reproductive and sexual characteristics, were significantly associated with the use of modern contraceptive (p < 0.05).

In a multilevel logistic regression model (Table 3), women aged 35–39 years had higher odds [aOR = 1.69, 95% CI (1.58–1.80)] of using MC compared with women aged 15–19 years. Women with no formal education were less likely to use MC [aOR = 0.4, 95% CI (0.38–0.44)] compared with women with higher education. Living in rural areas was less associated [aOR = 0.76; (0.72–0.89)] with the use of MC compared with living in urban areas. Women who were Christians were more likely to use MC than other types of religion (aOR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.17–1.38). Being poor/poorest [aOR = 0.76, 95% CI (0.73–0.79)] and belonging to the middle-class wealth index [aOR = 0.98, 95% CI (0.80–1.20)] were less associated with the use of modern contraceptive use compared with rich or richest women. Women with 5–7 children were more likely to use MC [aOR = 1.27, 95% CI (1.17–1.38)].

Table 3.

Factors associated with the use of modern contraceptive use among women (15–49 years)

| aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| 15–19 | 1.24 (1.13–1.35)** |

| 20–24 | 1.66 (1.55–1.79)** |

| 25–29 | 1.68 (1.56–1.79)** |

| 30–34 | 1.67 (1.56–1.78)** |

| 35–39 | 1.69 (1.58–1.80)** |

| 40–44 | 1.58 (1.48–1.70)** |

| 45–49 | 1 |

| Education | |

| No education | 0.40 (0.38–0.44)** |

| Primary | 0.82 (0.77–0.88)** |

| Secondary | 0.89 (0.84–0.95)* |

| Higher | 1 |

| Highest educational level of husband/partner | |

| No education | 1 |

| Primary | 1.33 (1.17–1.50)** |

| Secondary | 1.26 (1.10–1.43)* |

| Higher | 1.30 (1.10–1.54)* |

| Don’t know | 1.24 (0.93–1.68) |

| Marital status | |

| Never in union | 1 |

| Married | 2.66 (2.50–2.83)** |

| Living with partner | 1.68 (1.57–1.80)** |

| Other (widowed/divorced) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99)* |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 1 |

| Rural | 0.76 (0.72–0.89)** |

| Employment | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 1.3 (1.17–1.38)** |

| Islamic | 0.66 (0.60–0.72)** |

| Traditional | 0.46 (0.39–0.55)* |

| Other | 1 |

| Wealth Index | |

| Poorer/poorest | 0.76 (0.73–0.79)** |

| Middle | 0.89 (0.85–0.93)** |

| Richer/Richest | 1 |

| Age at first birth | |

| No birth | 1 |

| < 20 | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) |

| 20–29 | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) |

| 29+ | 0.56 (0.45–0.71)** |

| Number of living children | |

| None | 0.34 (0.27–0.42)** |

| 1–2 | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| 3–4 | 1.27 (1.17–1.39)** |

| 5–7 | 1.27 (1.17–1.38)** |

| 7+ | 1 |

| Number of sex partner (s) excluding spouse | |

| None | 1 |

| 1 | 4.22 (4.00–4.45)** |

| 2 | 7.31 (6.34–8.43)** |

| 3+ | 9.57 (6.62–13.84)** |

| Told of family planning at a health facility | |

| No | 0.69 (0.67–0.71)** |

| Yes | 1.00 |

| Heard of family planning on Media | |

| No | 0.77 (0.74–0.79)** |

| Yes | 1.00 |

| Knowledge of modern method | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 303.8 (89.9–1027.5)** |

| Fieldworker visited and talked about family planning | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.53 (1.39–1.68)** |

| Visited health facility last 12 months | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.26 (1.16–1.36)** |

Multiple logistic regression: Dependent variable—use of modern contraceptive (use/non-use)

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. 1-Reference category

**p < 0.001; *p < 0.01

Having more (3+) multiple sexual partners excluding spouse was associated with higher odds [aOR = 9.57, 95% CI (6.62–13.84)] of the use of MC compared with having no multiple sexual partners. Women who were not told of family planning at a health facility were less likely [aOR = 0.69, 95% CI (0.67–0.71)] to use MC compared with women who had heard family planning from a health facility. Knowing any modern method of contraceptive was 303.8 times associated with the use of MC [aOR = 303.8, 95% CI (89.9–1027.5)] than those who did not know any method. Women who had not heard of family planning from television, radio, and text messages (media as a source of information) were less likely to use MC [aOR = 0.77, 95% CI (0.74–0.79)] compared with those who have heard of family planning from the media.

Discussion

Family planning is one of the investments that can be made to help achieve most of the United Nation’s sustainable development goals especially poverty reduction, quality education, decent work and economic growth, and good health and well-being. The use of MC is a safe and effective method to regulate fertility and ensure the well-being of women of reproductive age. Coverage and factors associated with the use of MC vary across the globe including sub-Saharan Africa countries.

In this study, the pooled prevalence of MC use was low, 22.0%; with country-specific variations. Namibia recorded the highest reproductive women using MC (49.7%) with the least in Central Africa Republic (3.5%). This finding is similar to a recent study using secondary data of DHS in 29 sub-Saharan Africa countries on predictors among adolescent and young women, where Ahenkorah [22] reported a prevalence of 24.7%. Again, the finding is in agreement with a study by Apanga et al. [8] who used data from multiple indicator cluster surveys across 20 Africa countries. The authors reported an overall prevalence of 26% ranging from 6% in Guinea and 62% in Zimbabwe. In addition, this finding is also consistent with country-specific DHS studies [9, 16, 23–27].

The most common type of contraceptives used were injections (39.4%), condoms (17.5%), and implants (26.5%). Earlier studies have reported similar findings [9, 12]. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use include age, women’s educational level, educational level of husband/partner, place of residence, employment, marital status, wealth index, number of living children, been told of family planning at a health facility, number of sex partners excluding the spouse, heard family planning on the media (television, radio, newspaper, text messages), knowledge of modern method and a visit by a health worker to discuss family planning.

In this present study, younger aged women (15–19 years) were less likely to use MC compared to older old women (35–39 years). This could be due to the fact that, these old women were having more children and would want to limit or space the number of pregnancies than the younger women who may have few or no children. This was confirmed in the findings where women with more children were less likely to use modern contraceptives. This finding is in line with previous studies [12, 28] but contradicts the findings of these studies [22, 29] where younger women were more likely to use modern contraceptives.

In most African countries family planning is part of integrated health care. Health workers continue to play a major role in encouraging the use of MC by providing couples with the knowledge that enables them to make informed reproductive decisions including the use of MC [30]. Findings from this study indicate that women who had received family planning information from health workers were more likely to use MC than those who did not. This is in agreement with the study by Kebede and colleagues [12].

Women residing in rural areas were less likely to use MC than those in urban settings. This could be due to accessibility, availability, and lack of information on the use of MC in these settings. Consistent with this finding is the study by Kebede et al., Ontiri et al. and Mahmood and Ringheim [12, 19, 31].

The media serves as a source of information and is mostly used to provide vital information to the public. In this study, women who reported receiving information from the media (television, radio, newspaper, text messages) or exposed to the media were more likely to use modern contraceptives. This is similar to earlier studies that reported on the strong influence and association of the media and uptake of MC [32, 33].

Having adequate reproductive knowledge helps with better decisions. A finding from this study is that knowledge of any method of contraceptives was significantly associated with the use of modern contraceptives. This is in agreement with previous studies [12, 34]. It is therefore imperative that much reproductive information is provided to women to increase their knowledge to guide good reproductive decisions to improve their health and well-being.

Strength and limitation of the study

The strength of this study is the large population-based sample size used in the study which increased the power of the study. This enables the generalizability of the findings of modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age. However, the study was limited by the use of secondary data restricting study variables.

Conclusion

There was a low pooled prevalence (22.0%) of the use of MC across the 37 countries used in sub-Saharan Africa. This showed a considerable variation from as low as 3.5% in the Central Africa Republic to 49.7% in Namibia. The most common type of contraceptives used were injections (39.4%), condoms (17.5%), and implants (26.5%). Socio-demographic, sexual characteristics factors were found to be associated with the use of modern contraceptives. The low prevalence of modern contraceptive use recorded in this study infers that there should be more education particularly in the health facility and the media to increase knowledge and uptake of MC use among women of reproductive age.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the DHS program for making data available for the study.

Abbreviations

- DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- MC

Modern contraceptive

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- LAM

Lactational Amenorrhea Method

- IUD

Intra-Uterine Devices

- FP

Family planning

Authors’ contributions

IB designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft, and approved the final manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets and materials supporting our findings are available from the DHS program website. I acknowledge all reviewers for their useful comments.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required for the study as secondary data were used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.United Nations Sustainable development goals. Goals 3; Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages; Targets and Indicators. 2019. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3. Accessed 20 May 2021.

- 2.WHO. Family planning/contraception methods. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planning-contraception. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

- 3.Cahill N, et al. Modern contraceptive use, unmet need, and demand satisfied among women of reproductive age who are married or in a union in the focus countries of the Family Planning 2020 initiative: a systematic analysis using the Family Planning Estimation Tool. Lancet. 2018;391(10123):870–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Festin MPR, et al. Moving towards the goals of FP2020—classifying contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;94(4):289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marquez MP, Kabamalan MM, Laguna E. Traditional and modern contraceptive method use in the Philippines: trends and determinants 2003–2013. Stud Fam Plan. 2018;49(2):95–113. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frost JJ, Lindberg LDJC. Reasons for using contraception: perspectives of US women seeking care at specialized family planning clinics. Contraception. 2013;87(4):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starbird E, et al. Investing in family planning: key to achieving the sustainable development goals. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(2):191–210. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apanga PA, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 20 African countries: a large population-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e041103. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebre MN, Edossa ZK. Modern contraceptive utilization and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: evidence from 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00923-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andi JR, et al. Modern contraceptive use among women in Uganda: an analysis of trend and patterns (1995–2011) Etude Popul Afr. 2014;28(2):1009–1021. doi: 10.11564/28-0-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson OE. Determinants of modern contraceptive uptake among Nigerian Women: evidence from the national demographic and health survey. Afr J Reprod Health. 2017;21(3):89. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kebede A, et al. Factors affecting demand for MCamong currently married reproductive age women in rural Kebeles of Nunu Kumba district, Oromia, Ethiopia. Contracept Reprod Med. 2019;4:21. doi: 10.1186/s40834-019-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palamuleni ME. Socio-economic and demographic factors affecting contraceptive use in Malawi. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;13(3):331–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solanke BL. Factors influencing contraceptive use and non-use among women of advanced reproductive age in Nigeria. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s41043-016-0077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tawiah EO. Factors affecting contraceptive use in Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 1997;29(2):141–149. doi: 10.1017/S0021932097001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nonvignon J, Novignon J. Trend and determinants of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Ghana. Afr Popul Stud. 2014;28:956–967. doi: 10.11564/28-0-549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aviisah PA, et al. Modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Ghana: analysis of the 2003–2014 Ghana demographic and health surveys. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achana FS, et al. Spatial and socio-demographic determinants of contraceptive use in the Upper East region of Ghana. Reprod Health. 2015;12:29. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ontiri S, et al. Patterns and determinants of modern contraceptive discontinuation among women of reproductive age: analysis of Kenya Demographic Health Surveys, 2003–2014. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ba DM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 17 sub-Saharan African countries: a large population-based study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2019;21:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson R, et al. Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1233–1240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahinkorah BO. Predictors of modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: a mixed effects multilevel analysis of data from 29 demographic and health surveys. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40834-020-00138-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakew Y, et al. Geographical variation and factors influencing modern contraceptive use among married women in Ethiopia: evidence from a national population based survey. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aviisah P, et al. Modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Ghana: analysis of the 2003–2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butame SA. The prevalence of modern contraceptive use and its associated socio-economic factors in Ghana: evidence from a demographic and health survey of Ghanaian men. Public Health. 2019;168:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandiwa C, et al. Factors associated with contraceptive use among young women in Malawi: analysis of the 2015–16 Malawi demographic and health survey data. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:12. doi: 10.1186/s40834-018-0065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worku AG, Tessema GA, Zeleke AA. Trends of modern contraceptive use among young married women based on the 2000, 2005, and 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys: a multivariate decomposition analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):e0116525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takele A, Degu G, Yitayal M. Demand for long acting and permanent methods of contraceptives and factors for non-use among married women of Goba Town, Bale Zone, South East Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2012;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grindlay K, et al. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy among young women and men in Accra, Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabagenyi A, et al. Modern contraceptive use among sexually active men in Uganda: does discussion with a health worker matter? BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmood N, Ringheim K. Factors affecting contraceptive use in Pakistan. Pak Dev Rev. 1996;35:1–22. doi: 10.30541/v35i1pp.1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajoga UA, Atagame KL, Okigbo CC. Media influence on sexual activity and contraceptive use: a cross sectional survey among young women in urban Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2015;19(3):100–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutaremwa G, et al. Predictors of modern contraceptive use during the postpartum period among women in Uganda: a population-based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1611-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weldegerima B, Denekew A. Women's knowledge, preferences, and practices of modern contraceptive methods in Woreta, Ethiopia. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2008;4(3):302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets and materials supporting our findings are available from the DHS program website. I acknowledge all reviewers for their useful comments.