Abstract

Purpose: We explored physiotherapists’ perceptions of clinical supervision. Method: Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 21 physiotherapists from a public hospital. Qualitative analysis was undertaken using an interpretive description approach. The Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (MCSS–26) was administered to evaluate the participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the clinical supervision they had received and to establish trustworthiness in the qualitative data by means of triangulation. Results: The major theme was that the content of clinical supervision should focus on professional skill development, both clinical and non-clinical. Four subthemes emerged as having an influence on the effectiveness of supervision: the model of clinical supervision, clinical supervision processes, supervisor factors, and supervisee factors. All sub-themes had the potential to act as either a barrier to or a facilitator of the perception that clinical supervision was effective. Conclusions: Physiotherapists reported that clinical supervision was most effective when it focused on their professional skill development. They preferred a direct model of supervision, whereby their supervisor directly observed and guided their professional skill development. They also described the importance of informal supervision in which guidance is provided as issues arise by supervisors who value the process of supervision. Physiotherapists emphasized that supervision should be driven by their learning needs rather than health organization processes.

Key Words: education, mentors, organization and administration, qualitative research, staff development

Abstract

Objectif : explorer les perceptions des physiothérapeutes à l’égard de la supervision clinique. Méthodologie : entrevues individuelles semi-structurées réalisées auprès d’un échantillon choisi de 21 physiothérapeutes d’un hôpital public. Les chercheurs ont procédé à une analyse qualitative au moyen d’une description interprétative. Ils ont utilisé l’échelle de supervision clinique de Manchester (MCSS–26) pour évaluer les points de vue des participants à l’égard de l’efficacité de la supervision et pour établir la fiabilité des données qualitatives par triangulation. Résultats : un thème majeur est ressorti : la supervision clinique devrait être axée sur le perfectionnement d’habiletés professionnelles cliniques et non cliniques. Il a été établi que quatre sous-thèmes avaient une influence sur l’efficacité de la supervision : le modèle de supervision clinique, les processus de supervision clinique, les facteurs liés au superviseur et ceux liés au supervisé. Ces sous-thèmes avaient tous le potentiel d’être un obstacle ou un incitatif à la perception d’efficacité de la supervision clinique. Conclusion : selon les physiothérapeutes, la supervision clinique la plus efficace était axée sur le perfectionnement de leurs habiletés professionnelles. Ils préféraient un modèle de supervision directe, selon lequel leur superviseur observait directement et orientait le perfectionnement de leurs habiletés professionnelles. Ils ont également insisté sur l’importance de la supervision informelle, c’est-à-dire que les superviseurs qui adhèrent à l’importance du processus de supervision donnent des conseils à mesure que des problèmes surgissent. Ils ont souligné que la supervision devrait être dictée par leurs besoins d’apprentissage plutôt que par les processus de l’organisation hospitalière.

Mots-clés : : enseignement, formation, mentors, organisation et administration, perfectionnement du personnel, recherche qualitative

National and provincial standards recommend that physiotherapists participate in regular clinical supervision to ensure patient safety and high quality of care.1–4 These standards and the practice of clinical supervision of physiotherapists can vary among health care settings, provinces, and countries. For example, Australian and New Zealand guidelines recommend that clinical supervision be provided to physiotherapists throughout their professional career.1,4 Canadian guidelines require new graduate physiotherapists to be supervised until they reach a level of competency in their practice, determined by reaching predetermined standards or demonstrating the professional and clinical care behaviours expected of physiotherapists.2,3 Clinical supervision involves an experienced physiotherapist guiding the practice of a less experienced physiotherapist.5–7 It aims to bridge the gap in professional experience, ensuring that patient care is not negatively affected by a therapist’s inexperience.5–7

Clinical supervision is also intended to support physiotherapists in their professional role. Proctor’s model of clinical supervision describes how health professionals can be supported in three domains of practice: formative, restorative, and normative.8 The formative domain refers to the development of skills specific to therapists’ professional role; the restorative domain refers to supporting therapists through the emotional burden of their professional role; and the normative domain refers to supporting therapists to achieve compliance with standards of care and organizational policies and procedures.8 Proctor’s model provides a framework for clinical supervision and has been adopted by health professionals, including physiotherapists.9,10 Research has proposed that effective clinical supervision should support therapists in all three domains.11

The model of clinical supervision used by physiotherapists can vary. Some guidelines recommend a reflective model of supervision, whereby supervisees reflect on and analyse their workplace experiences, identify learning and development opportunities, and deconstruct both the cognitive and the emotional aspects of their work role.12–14 Given its focus on both professional development and emotional support, reflective supervision is thought to be an essential component of clinical supervision for therapists in Proctor’s domains.15

Clinical supervision can also be practised using a direct model, whereby a supervisor observes a physiotherapist’s clinical practice.2,16 This model enables the supervisor to directly influence the care that is provided and help supervisees to learn clinical skills in a context-specific environment. It is particularly recommended when supervisees are inexperienced or learning a new skill.2

There is uncertainty about how effective clinical supervision actually is in supporting physiotherapists in their professional role.17,18 On the basis of therapists’ reports using the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (MCSS–26),19 Snowdon and colleagues found that clinical supervision was ineffective for more than half the physiotherapists (n = 60) surveyed.18 Similarly, Gardner and colleagues found that, on average, physiotherapists (n = 25) scored lower than the threshold effectiveness score.17 These findings indicate that for many physiotherapists, clinical supervision as practised may have limited effectiveness in supporting them in their professional role.

Redpath and colleagues provided insights into the ideal structure and content of clinical supervision for physiotherapists.20 They reported that clinical supervision should cover a variety of workplace issues and involve scheduled and unscheduled sessions and that physiotherapist being supervised should be prepared to take responsibility for leading the supervision session.20 However, what remains unknown is why physiotherapists often perceive clinical supervision to be ineffective and what aspects of clinical supervision require focus to effectively support them. Qualitative analysis asking physiotherapists about their experiences of clinical supervision may provide insight into which aspects of clinical supervision are effective and which are not. It might also inform a redesign of clinical supervision to better suit physiotherapists’ needs.

Therefore, by exploring physiotherapists’ experiences, we attempted to answer the following research question: What aspects of clinical supervision do physiotherapists perceive to be effective in supporting them in their professional role?

Methods

Design

Our study had a two-pronged approach. We used qualitative research methods in semi-structured interviews to explore physiotherapists’ experiences with clinical supervision and the aspects of supervision that they perceived to be effective. An interpretive description methodological approach was used to gain a better understanding of the practice of clinical supervision and to generate knowledge that could be applied in the future supervision of physiotherapists.21–23 We also conducted a concurrent quantitative descriptive survey using the MCSS–26 to document the effectiveness of clinical supervision.19

This study received ethics approval from the health network ethics committee (LR21-2018), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

The participants were registered physiotherapists working in hospital-based services at six hospital sites of a public health network in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Physiotherapists working solely in community outpatient services operated in a separate department with a different supervision structure and were ineligible to participate. Eligible physiotherapists who expressed interest in participating were selected by means of purposive sampling to ensure that the sample represented the diversity of the health network.

A total of 21 physiotherapists participated in the study. Of these, 15 (71%) were women, and their average age was 33 years. Seven participants (33%) were Grade 1 (junior) physiotherapists, 9 (43%) were Grade 2 (mid-level) physiotherapists, and 5 (24%) were Grade 3 or 4 (senior) physiotherapists. Ten participants (48%) worked on acute hospital wards, 8 (38%) worked on sub-acute (rehabilitation) wards, 2 (10%) worked in emergency departments, and 1 (5%) worked in a hospital outpatient setting. Five participants (24%) specialized in geriatric evaluation and management, 3 (14%) specialized in cardiorespiratory, 3 (14%) in orthopaedics or musculoskeletal, and 3 (14%) in neurology; the 7 (33%) Grade 1 participants rotated through these clinical specialities.

Clinical supervision policy and procedures

The physiotherapists who participated in this study were guided in their clinical supervision practice by a health network guideline. The guideline was not specific to physiotherapists but encompassed all allied health professionals. The guideline’s recommendations for the content of supervision are broad but align with Proctor’s model: that physiotherapists receive support as they develop their professional skills, meet the organizational requirements, and manage the emotional burden of practice. Clinical supervision may include a reflective or direct model of supervision. Physiotherapists are required to receive supervision from a more senior physiotherapist. The frequency of supervision sessions is dictated by grade level: Grade 1 therapists participate once a week or once every 2 weeks, and all higher grades participate once a month.

All physiotherapists working in the health network are expected to participate in supervision. Supervision occurs during paid working hours, and a physiotherapist being supervised is responsible for ensuring that supervision occurs. Supervisors are generally allocated to physiotherapists on the basis of their clinical speciality and hospital site. Supervisors have a higher grade (ranging from Grade 1 to Grade 4) than physiotherapists, and their non-clinical responsibilities increase with each grade level.

Data collection

First, the participants completed the MCSS–26.19 We used this questionnaire to evaluate the participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the clinical supervision they had received and to establish trustworthiness in the qualitative data by means of triangulation. The participants were asked to rate the level to which they agreed with each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4). The MCSS–26 consists of six sub-scales, which can be summed to provide a summary score for each of Proctor’s domains. This sum provides a total score; a score of 73 or more indicates that supervision is effective.19 The scale has demonstrated evidence of validity in the allied health professions.24

Next, one researcher (DAS) who worked in the research department of the participating health service but who had no supervisory or clinical duties conducted semi-structured interviews. Interviews took place in a private room in the physiotherapy department at each hospital site. An interview guide (reproduced in Table 1) was used to ensure that relevant topics were addressed.

Table 1 .

Semi-Structured Interview Guide

| Topic | Sample questions |

|---|---|

| What is the role of clinical supervision? | What do you feel is the purpose of supervision? |

| What areas of your professional role do you feel supervision should support you in? | |

| What is your experience of effective clinical supervision? | What activities do you do during supervision that you feel support you in your professional role? |

| What do you feel are the enablers of these activities? | |

| What do you feel are the barriers to these activities? | |

| What other things have you experienced during supervision in the past that you found effective or didn’t find effective? | |

| What are your ideals regarding clinical supervision? | Are there activities that you’re not doing during supervision at the moment that you would like the opportunity to participate in? |

| Why do you feel that you currently don’t have the ability to participate in these opportunities? | |

| Is there anything else that you feel could happen to better support you with clinical supervision? |

Data analysis

The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions were then given to the participants to verify that they accurately represented their perceptions;25 the participants were encouraged to amend the transcripts when they thought that they did not communicate what they had intended to say or when they wanted to add information. Three participants returned transcripts with minor corrections or clarifications relating to spelling errors and inaccurate transcription of individual words. After the amended transcripts were returned, identifying information was removed, and each transcript was assigned a number for further analysis.

The interpretive description approach was used to focus on the practice of clinical supervision with the intention of producing findings that could have a positive impact on its practice and effectiveness.21–23 Interpretive description provides a flexible structure for inductively describing a phenomenon (effective clinical supervision) and understanding it from the perspective of those experiencing it (the physiotherapists).21–23 Interpretive description consists of two philosophical underpinnings: (1) reality is subjective, constructed, and contextual and (2) a researcher and participant interact to generate research understandings.22 Inductive thematic analysis was used as an analytic approach because it is consistent with interpretive description methods and has been used in previous studies using interpretive description.21 This approach ensured that themes were generated from our interpretation of the participants’ experiences with clinical supervision.

The rigor of data analysis was enhanced by using a reflective diary to document the researcher’s (DAS’s) observations and experiences during the interviews.26 Changes to interviewing style, including greater use of open-ended questions, were made according to these reflections. Two researchers (DAS, SC) examined the data line by line and independently coded the transcripts, 320 A4-size pages in total, using NVivo, Version 12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Victoria). This qualitative data analysis software was used to help organize and manage the data.

The next step was to examine connections and comparisons among the codes to develop themes and sub-themes. Four additional researchers (KL, GS, KW, and NFT) read the transcripts and provided an overview impression. After codes and themes were assigned and themes were independently identified, all researchers met to discuss the themes. Consensus among all researchers on the emerging themes was achieved collaboratively through discussion. Two researchers (DAS, SC) then re-read the transcripts to search for data related to the identified themes (selective coding) and to confirm the themes. No new themes arose, suggesting that saturation had been achieved.27 Links and relationships among the confirmed themes and the subthemes were established, and an overarching theme was formulated. Trustworthiness was established by means of triangulation with the MCSS–26 scores (methodologic triangulation) and among researchers (investigator triangulation).28

Results

Effectiveness of clinical supervision and supervision characteristics

The participants’ median MCSS–26 score was 74 (range, min-max, 63–94) with 12 of the 21 participants reporting that clinical supervision was effective. The participants rated clinical supervision least effective in the normative domain of the MCSS–26 (see Table 2), and in this domain, they scored lowest on the Finding Time subscale. On average, the participants had received clinical supervision for 5 years and typically participated in monthly clinical supervision sessions lasting 30–60 minutes. The most common model of clinical supervision was reflective, with sessions scheduled separately from clinical practice.

Table 2 .

Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale Scores

| Domain, range (min-max) | Median (range, min-max)* | Median (range, min-max)† |

|---|---|---|

| Total score, 0–104 points | 74 (63–94) | 71 (61–90) |

| Formative, 0–28 points | 21 (16–25) | 75 (57–89) |

| Improved Care/Skills, 0–16 points | 12 (8–15) | 75 (50–94) |

| Reflection, 0–12 points | 9 (5–11) | 75 (42–92) |

| Restorative, 0–40 points | 31 (20–40) | 78 (50–100) |

| Trust/Rapport,0–20 points | 16 (10–20) | 80 (50–100) |

| Supervisor Advice/Support, 0–20 points | 15 (8–20) | 74 (40–100) |

| Normative, 0–36 points | 24 (18–35) | 67 (50–97) |

| Importance/Value of Clinical Supervision, 0–20 points | 16 (10–20) | 80 (50–100) |

| Finding Time, 0–16 points | 8 (3–15) | 50 (19–94) |

Raw score.

Out of 100.

Theme and subthemes

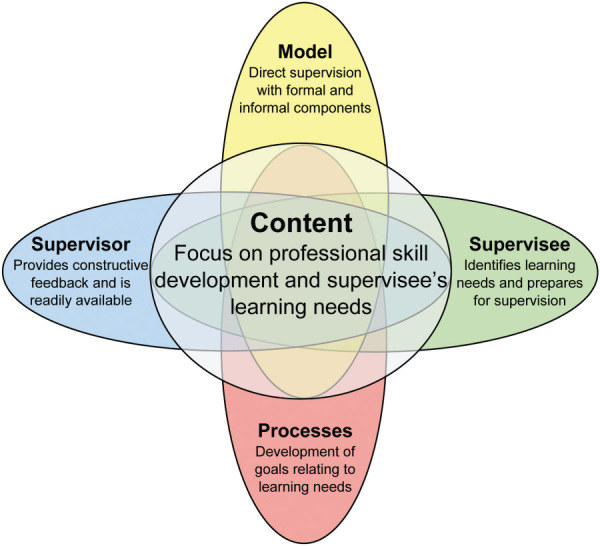

One main theme and four subthemes emerged. The main theme was that the content of clinical supervision should focus on professional skill development, including both clinical and non-clinical skills. Four subthemes were identified by participants as having a significant influence on the perceived effectiveness of clinical supervision: the model of clinical supervision, the clinical supervision process, supervisor factors, and supervisee factors. The main theme and four subthemes interact with each other and have the potential to be either a barrier to or a facilitator of the perceived effectiveness of clinical supervision (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Effective clinical supervision of physiotherapists.

Theme: content of clinical supervision should focus on professional skill development

The participants emphasized that effective clinical supervision must focus on the development of skills that are relevant to their professional role: “There are two components, to help us progress in our treatment of patients and develop our clinical skills, but then also to help develop our non-clinical skills” (P9).

They believed that clinical supervision that focused on exploring the emotional impact of their professional role was a less valuable process than focusing on the development of skills. “You can go down too far of the line of being just sympathetic to grievances and whingeing [that] doesn’t necessarily usually achieve very much” (P11). They expressed the importance of clinical supervision addressing their learning needs. “[The purpose of clinical supervision is] making sure your learning needs are met and you can progress to the next level” (P8).

The participants’ learning needs were commonly dictated by their experience. Whereas all the participants reported that their clinical supervision had focused on clinical skill development, those at a senior level of experience (Grade 3 or 4) were much more likely to report that it had focused on the non-clinical aspects of their professional role as they took on greater responsibilities for non-clinical tasks.

Subtheme: model of clinical supervision

To improve their clinical skills, participants at all levels of experience reported that a direct model of clinical supervision should be used. This would involve a collaborative process in which a supervisor observed how they managed their patients and assisted with treatment: “I find that having actual clients or patients there, hands on supervision quite helpful ’cause then you can actually deal with a real person and problem solve together and learn practically” (P7). The participants also reported that direct supervision was most effective when it was structured and when they were offered the opportunity to reflect on their performance after a session. Direct supervision was also perceived to be effective in facilitating non-clinical skill development. “We are working on a research project together which is clinically based on the wards. And my supervisor assists by teasing out any issues there, monitoring timeframes and how it’s all progressing” (P8). They noted that reflective supervision was mostly used to establish their learning needs, their goals, and a career plan. This model of clinical supervision was also effective for discussing the operational aspects of their professional role, but it was less effective for skill development.

Participants also emphasized the importance of receiving clinical supervision that was responsive to issues as they arose. This form of supervision was commonly referred to as “informal” and enabled a participant to be supported in a timely manner: “I think the informal, the strength of that is it’s timely, generally at the time that you have the problem or close enough to” (P17).

In addition, the participants recognized the importance of receiving clinical supervision that had been planned in advance. This form of supervision was commonly referred to as “formal” and could involve a co-treatment session or a face-to-face meeting, during which participants discussed their learning needs and established goals: “I definitely feel the value of sitting down face to face, it feels more deliberate and adds value to the supervision session … it guides my practice and guides my work for the next month as well” (P19).

They reported that informal and formal components complemented each other. However, they were unsure whether the informal component was recognized by their health organization and physiotherapy management as a form of clinical supervision: “It may look like I haven’t been supervised for months, but actually I’ve been supervised really well every day in my opinion. It’s just I haven’t set a time to sit down and talk, and fill in some paperwork” (P14).

Subtheme: clinical supervision processes

The participants reported that clinical supervision processes should focus on their professional development. Key to this was agreement between the supervisor and the supervisee on the content, frequency, model, roles, and documentation of supervision. The participants also described the importance of developing goals and action plans specific to their learning needs: “I find it helpful being accountable to the supervisor. Being able to talk through my goals for the quality project and my goals and the progress that I’ve made towards them” (P20). They thought that supervision should be provided at a frequency that met their needs and facilitated the development of skills rather than a frequency dictated by their grade level: “As a Grade 3 I could be having just monthly supervision, but the reality is that I need [it] more frequent[ly] than that” (P18).

Documentation was viewed as a useful process for ensuring continuity in setting goals and facilitating supervisees’ accountability for attaining those goals. However, focusing on documenting the content of sessions and discussions held during sessions was seen as being non-productive: “I’ve had supervisors in the past just go through the process and be really fixated on the form … but unless it’s actually meaningful to you in achieving something, why waste your time with all the paperwork?” (P5). These processes were perceived to exacerbate the issue of finding time for clinical supervision, a result that aligned with the results of the MCSS–26: “When the staff as a whole are saying ‘We don’t have time for supervision anyway,’ I think then a laborious bit of paperwork adds to it” (P3). This focus on compliance with organizational requirements was seen to be counterproductive to supporting therapists in their professional role and created confusion about the purpose of clinical supervision.

Theme: supervisor factors

The participants reported that a supervisor must possess the appropriate professional skills and qualities to facilitate effective clinical supervision. The ability to focus supervision on a participant’s professional development was perceived to be crucial to its overall effectiveness.

Another quality that participants thought supervisors should possess was the ability to provide honest and constructive feedback on their professional performance: “Having a supervisor that’s quite transparent and honest with you and provides you with some sort of feedback … if you keep getting told you’re fabulous you’re not going to get better” (P5).

The participants also stated that supervisors should work in close proximity with their supervisees and be readily available because that helped to build rapport in the supervisory relationship and ensured that feedback was accurate and relevant:

You can give feedback from afar and say “I can see you’re a great team player” and “I can see that you get your work done” … but to actually have feedback on your actual performance or an interaction or your rapport or your manner, I believe you need to at least spend some time with that person. (P3)

When supervisors did not possess these qualities or when they focused on the organizational requirements of supervision, the participants had poorer relationships with them and less effective supervision:

I just felt they didn’t have time … I didn’t feel that they were very invested in me, and I think we did only a couple of supervision sessions ’cause I didn’t want to initiate it. (P8)

I’ve had supervisors in the past just go through the process and be fixated on the form. Making sure the form’s filled out properly and do this for the form and make sure the form’s right and write it like this because of the form, but it doesn’t actually mean anything. (P6)

Theme: supervisee factors

For clinical supervision to be effective, the participants acknowledged that they must be engaged in the practice and take responsibility for their learning: “The effectiveness is guided by what I want from it, so I have to know how I learn and what I want” (P1).

To facilitate clinical supervision that focused on a physiotherapist’s professional development the supervisee had to prepare for the sessions: “Particularly going through a formal plan is best and the more prepared you are the better. It never works when the supervisee turns up unprepared … if I’m not prepared I would rather delay or postpone the supervision” (P14).

The participants reported that the ability to use supervision effectively for their professional development required skill that was learned through exposure to high-quality clinical supervision and competent supervisors.

I think it’s not until you’ve got some experience in receiving supervision and giving supervision that you can actually go, “Well actually here’s kind of an area where I think we can make this more meaningful or this can be more meaningful for me as a supervisee.” (P21)

Discussion

We found that the physiotherapists perceived that, for clinical supervision to be effective, it was essential that it focus on professional skill development. Moreover, the model of supervision, supervision processes, supervisor, and supervisee could all influence whether clinical supervision was effective. Specifically, supervision was perceived to be effective when it addressed problems as they arose, a direct supervision model was used, the supervision processes focused on facilitating the development of the supervisee, the supervisor was readily accessible, and both the supervisor and the supervisee possessed the skills required to facilitate the supervisee’s professional development.

Despite Proctor’s model, which emphasizes the importance of exploring the emotional burden of practice, our findings suggest that physiotherapists perceive the need for a greater focus on professional skill development. This does not mean that they do not require emotional support, but it does indicate that they feel better supported when their professional development is the primary focus of clinical supervision. Therefore, physiotherapists may benefit from training in skills such as goal setting, providing constructive feedback, and critically evaluating professional practice, all of which may facilitate their professional development. This training may improve the effectiveness of their clinical supervision.

Physiotherapists’ preference for a focus on professional skill development may be explained by their preferred learning style. They often prefer active learning styles whereby they learn through hands-on experience and applying previously attained knowledge.29 This contrasts with other allied health professionals such as social workers and psychologists, who prefer to reflect on previous experiences and explore their emotions.30 Physiotherapists’ preferred learning styles are likely reinforced by their undergraduate education and ongoing practice with colleagues who have similar learning styles.31 Hence, they prefer that their clinical supervision be tailored to fit their learning style and focus on developing their professional skills while avoiding components of clinical supervision, such as reflecting on the emotional burden of practice, that do not fit their preferred style.

These results raise the issue of whether physiotherapists should be provided with what they think they need (i.e., skill development) or with further training to enhance their skills in dealing with emotional issues. The latter would likely require advanced training of physiotherapy supervisors, and an alternative solution may be inter-professional supervision in which health professionals with expertise in counselling, such as psychologists or social workers, provide this form of restorative clinical supervision.32

Our results suggest that enhancing the opportunities for physiotherapists to participate in direct and informal supervision may improve the effectiveness of clinical supervision overall. Medical residents have also reported a preference for direct and informal supervision, especially for the purpose of learning practical clinical skills.33 Therefore, the direct model may be most appropriate for health professionals who require hands-on practical skills in managing their patients. Their patients will also likely benefit from direct models of clinical supervision because direct supervision has been shown to enhance patient safety and quality of care.34,35 However, in some health care settings physiotherapists and their professional organizations have adopted a model of clinical supervision that is predominantly reflective.4 This may be because of a preference for the reflective model in the wider allied health professions and a focus on developing a common clinical supervision policy for all allied health professionals.12,36 These guidelines may restrict the practice of the direct model of clinical supervision. Physiotherapy-specific guidelines that accommodate and support the practice of direct supervision may facilitate more effective clinical supervision of physiotherapists.

The convergence of our qualitative and quantitative (MCSS–26) data identified that finding time for clinical supervision was an issue and that organizational requirements such as completing documentation were a barrier to finding time. Given that finding time is a major contributor to effective clinical supervision of physiotherapists, supervision processes should be informed by a supervisee’s learning needs and not be too prescriptive.18 Organizational requirements are likely a reflection of the function of clinical supervision as a form of governance to ensure quality of care.1 For example, prescribing a certain frequency of sessions would give inexperienced therapists regular support but also act as a preventive measure, ensuring that their inexperience did not affect patient care. Similarly, a requirement that patient care be addressed during supervision would be considered reasonable but might conflict with the learning needs of therapists who wanted to focus on their non-clinical skill development at that time.

Therefore, the content of clinical supervision cannot be entirely driven by physiotherapists’ preferences because they may not meet the needs of the health organization. However, organizational requirements for clinical supervision should be flexible, should account for various learning needs, and could minimize processes that do not contribute to a supervisee’s development or patient care.

This study had several limitations. First, it included participants who worked in either an acute or a rehabilitation metropolitan public hospital. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized to physiotherapists who work in different settings, such as private practice or rural health. Physiotherapists who work in these settings may have different experiences with clinical supervision because of the relative isolation of their workplace compared with that of physiotherapists who work in metropolitan hospitals on large teams. Second, none of the participants worked in a mental health setting, and physiotherapists working in those settings may place greater emphasis on receiving emotional support for clinical supervision to be effective.

In addition, the participants consisted largely of junior to mid-level therapists; however, this distribution represents a typical public hospital staffing profile in which there are relatively few senior physiotherapist positions. If our sample had consisted of more experienced therapists, the results would likely highlight the importance of non-clinical skill development in this cohort. Finally, we considered only the effectiveness of clinical supervision for supporting therapists in their professional role, not for ensuring quality of care or patient safety. However, it is promising that physiotherapists prefer a direct model of clinical supervision, which has been shown to improve the quality and safety of patient care.34,35

Conclusion

The physiotherapists in our study reported that clinical supervision was most effective when it focused on their professional skill development. They preferred a direct model of supervision in which their supervisor directly observed and guided their professional skill development. They also emphasized the importance of informal supervision whereby guidance was provided as issues arose by supervisors who valued supervision. They emphasized that supervision should be driven by their learning needs rather than health organization processes. Developing a physiotherapy-specific guideline in the setting in which the study took place may result in greater effectiveness of clinical supervision for physiotherapists working in public health networks.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

There is uncertainty about the effectiveness of clinical supervision for supporting physiotherapists in their professional role. Physiotherapists have reported that clinical supervision should cover a variety of workplace issues and involve scheduled and unscheduled sessions, and the physiotherapist being supervised should be prepared to take responsibility for leading the session.

What this study adds

Physiotherapists prefer clinical supervision that primarily focuses on professional skill development. They also prefer a direct model in which their supervisor directly observes and guides their practice. Clinical supervision that primarily focuses on meeting health organization requirements will likely deter physiotherapists from participating in supervision; efforts should be made to consider physiotherapists’ learning needs when determining the content and delivery of supervision.

References

- 1.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . National safety and quality health standards: second edition [Internet]. Sydney (NSW): Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2017. [cited 2018. Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.College of Physical Therapists of Alberta . Supervision resource guide for physical therapists [Internet]. Edmonton: College of Physical Therapists of Alberta; 2008. [cited 2018. Aug 12]. Available from: https://physicaltherapy.med.ubc.ca/files/2012/05/Alberta-College-Supervision-Resource-Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.College of Physiotherapists of Manitoba . Supervised practice [Internet]. Winnipeg: College of Physiotherapists of Manitoba; 2016. [cited 2018. Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.manitobaphysio.com/wp-content/uploads/2.-Supervised-Practice-Information-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Physiotherapy New Zealand . Supervision in physiotherapy practice. Wellington: Physiotherapy New Zealand; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, et al. AMEE Guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach. 2007;29(1):2–19. 10.1080/01421590701210907. Medline:17538823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyth GM. Clinical supervision: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(3):722–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01329.x. Medline:10718893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milne D. An empirical definition of clinical supervision. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46(4):437–47. 10.1348/014466507X197415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proctor B. Enabling and ensuring: supervision in practice. In: Marken M, Payne M, editors. Supervision: a cooperative exercise in accountability. Leicester (UK): National Youth Bureau; 1986. p. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson M, Phillips P, Leggat S. Clinical supervision for allied health professionals: a systematic review. J Allied Health. 2013;42(2):65–73. Medline:23752232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sloan G, Watson H. Clinical supervision models for nursing: structure, research and limitations. Nurs Stand. 2002;17(4):41–6. 10.7748/ns2002.10.17.4.41.c3279. Medline:12430330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunero S, Stein-Parbury J. The effectiveness of clinical supervision in nursing: an evidence based literature review. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;25(3):86–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce P, Phillips B, Dawson M, et al. Content of clinical supervision sessions for nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic review. Clin Govern Int J. 2013;18(2):139–54. 10.1108/14777271311317927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todd G, Freshwater D. Reflective practice and guided discovery: clinical supervision. Br J Nurs. 1999;8(20):1383–9. 10.12968/bjon.1999.8.20.1383. Medline:10887822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann K, Gordon J, Macleod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595–621. 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. Medline:18034364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proctor B. Training for the supervision alliance. In: Cutcliffe JR, Hyrkäs K, Fowler J, editors. Routledge handbook of clinical supervision: fundamental international themes. London: Routledge; 2010. p. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cottrell D, Kilminster S, Jolly B, et al. What is effective supervision and how does it happen? A critical incident study. Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1042–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01327.x. Medline:12406264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner MJ, McKinstry C, Perrin B. Effectiveness of allied health clinical supervision: a cross-sectional survey of supervisees. J Allied Health. 2018;47(2):126–32. Medline:29868698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snowdon DA, Millard G, Taylor NF. Effectiveness of clinical supervision of physiotherapists: a survey. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(2):190–6. 10.1071/AH14020. Medline:25556758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winstanley J, White E. The MCSS–26 user manual. Sydney (NSW): Osman Consulting; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redpath AA, Gill SD, Finlay N, et al. Public sector physiotherapists believe that staff supervision should be broad ranging, individualised, structured, and based on needs and goals: a qualitative study. J Physiother. 2015;61(4):210–16. 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.08.002. Medline:26361812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Focus on qualitative methods. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(2):169–77. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods. 2004;3(1):1–21. 10.1177/160940690400300101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winstanley J, White E. The MCSS–26: revision of the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale using the Rasch measurement model. J Nurs Meas. 2011;19(3):160–78. 10.1891/1061-3749.19.3.160. Medline:22372092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45(3):214–22. 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214. Medline:2031523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan F, Coughlan M, Cronin P. Interviewing in qualitative research: the on-to-one interview. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2008;16(6):309–14. 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.6.42433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Öhman A. Qualitative methodology for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(5):273–80. 10.1080/16501970510040056. Medline:16208859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurmond VA. The point of triangulation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(3):243–58. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00253.x. Medline:11552552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stander J, Grimmer K, Brink Y. Learning styles of physiotherapists: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:2. 10.1186/s12909-018-1434-5. Medline:30606180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massey MG, Kim S, Mitchell C. A study of the learning styles of undergraduate social work students. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2011;8(3):294–313. 10.1080/15433714.2011.557977. Medline:21660824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolb AY, Kolb DA. The Kolb Learning Inventory Version 3.1: 2005 technical specifications. Boston: Hay Resources Direct; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson M, Phillips B, Leggat SG. Effective clinical supervision for regional allied health professionals – the supervisee’s perspective. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(1):92–7. 10.1071/AH11006. Medline:22513027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busari JO, Weggelaar NM, Knottnerus AC, et al. How medical residents perceive the quality of supervision provided by attending doctors in the clinical setting. Med Educ. 2005;39(7):696–703. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02190.x. Medline:15960790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snowdon DA, Hau R, Leggat SG, et al. Does clinical supervision of health professionals improve patient safety? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(4):447–65. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw059. Medline:27283436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snowdon DA, Leggat SG, Taylor NF. Does clinical supervision of healthcare professionals improve effectiveness of care and patient experience? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:786. 10.1186/s12913-017-2739-5. Medline:29183314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzpatrick S, Smith M, Wilding C. Quality allied health clinical supervision policy in Australia: a literature review. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(4):461–5. 10.1071/AH11053. Medline:23116979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]