Abstract

The new Light Cycler technology was adapted to the detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in clinical samples. Sera from 81 patients were tested by Light Cycler PCR, AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay, and in-house PCR. Our data demonstrate that Light Cycler is a fast and reliable method for the detection and quantitation of HCV RNA.

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) can usually be detected by serological assays. Difficulties may arise in patient populations with low or even absent antibody production, like immunosuppressed or hemodialysis patients (8, 12, 15). For those patients, detection of HCV RNA in a serum sample can prove whether the patient is infected or not. Moreover, when HCV infection is assumed to have occurred immediately prior to the examination, detection of the nucleic acid can significantly shorten the window phase (14). This situation and the demand for quantitative assays to monitor the viral load under antiviral therapy (6, 10) have led to the development of a variety of amplification procedures. Until now two different methodologies which satisfy the demand for real-time detection of nucleic acid amplification have been described (7, 17). Here we introduce a method using Light Cycler (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) technology for the detection of HCV RNA in serum samples from HCV-infected patients. Light Cycler is a commercially available system designed to decrease the time needed to achieve PCR results by monitoring amplification of target sequences in real time by a fluorimetric assay (17). This system has the advantage of providing accurate knowledge of the increment of amplification products in every single cycle. The results obtained by this assay were compared with results of the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay and of in-house PCR (4).

Serum samples were drawn from 81 patients with known chronic HCV infection, all of whom were confirmed antibody positive by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblot assay. No patient received antiviral treatment at the time of investigation.

RNA was extracted from sera by using a Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) Viral RNA kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The isolated RNA was resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated H2O, and cDNA synthesis was carried out with 50 pmol of primer 51 (5′-CCCAACACTACTCGCCTA-3′; nucleotides 269 to 252; numbering of nucleotide sequences as previously described [2]) and 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). Amplification was performed in 18 μl of Light Cycler DNA Master SYBR Green I mix containing 3.5 mM MgCl2 by using 2 μl of cDNA and primers 27 (5′-TCCACCATGAATCACTCCC-3′; nucleotides 27 to 43) and 150 (5′-CAGACCACTATGGCTCTCC-3′; nucleotides 150 to 132). PCR was performed in 45 cycles of 1 s at 95°C (denaturation), 3 s at 55°C (annealing), and 8 s at 72°C (extension), with fluorescence detection at 87°C after each cycle. After the final cycle, melting-point analysis of all samples and controls was performed within the range from 72 to 95°C. An external standard curve was generated by amplification of 10-fold dilutions of an HCV genotype 1b isolate (103 to 107 copies/ml) with each run. This approach has been proven for its reliability by (i) meeting the HCV standard (50,000 U) of the World Health Organization/National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (United Kingdom) International Scientific Working Group on the Standardization of Genome Amplification Techniques for Virological Safety Testing and (ii) repeatedly passing national trials of quality control cycles.

The AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Branchburg, N.J.) was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. The in-house HCV PCR and genotyping of HCV isolates were performed as previously described (4, 16). Statistical analysis was performed by using Spearman rank regression analysis.

Samples from 81 patients chronically infected with HCV were positive in all three PCR assays.

To investigate whether certain HCV genotypes are detected preferentially, the most frequent genotypes in our group of patients (16) were included, and no differences were observed (data not shown).

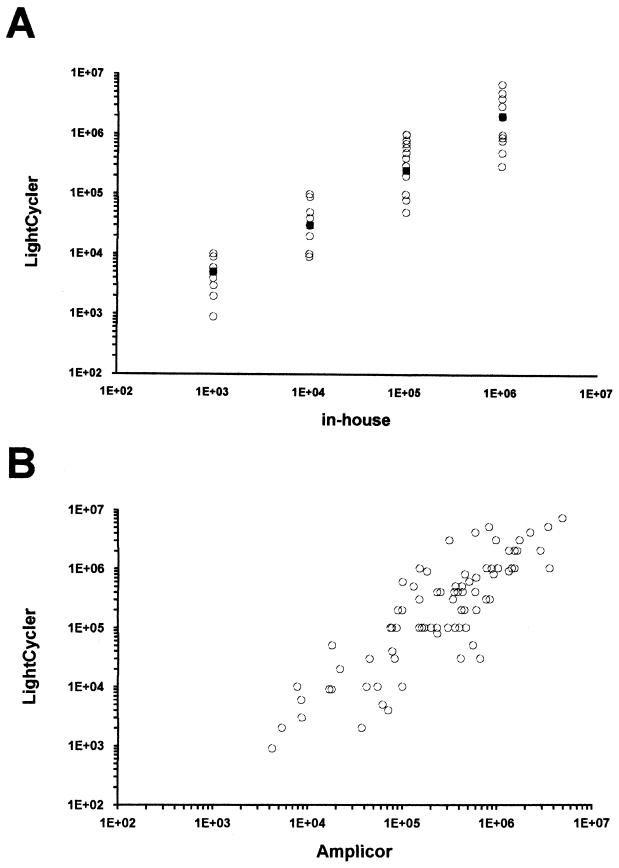

Quantitative titers ranged from 9 × 102 to 7 × 106 copies/ml (median, 7 × 105 copies/ml) as determined by Light Cycler PCR, from 4.2 × 103 to 4.8 × 106 copies/ml (median, 6 × 105 copies/ml) by the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay, and from 103 to 106 copies/ml (median, 105 copies/ml) by in-house PCR. The conformity of the quantitative titers between the Light Cycler PCR and the other two assays is shown in Fig. 1. All samples were tested in duplicate by Light Cycler, and high reproducibility was observed, with differences of no more than 0.2 log unit. The 30 samples from healthy blood donors were negative in all three assays.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of quantitative results obtained by Light Cycler with those obtained by in-house PCR (A) and those obtained by the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay (B). Solid squares in panel A indicate the respective median values of the Light Cycler results.

The Light Cycler system has the advantage that it provides accurate knowledge of the increment of amplification products in every single cycle. Simultaneous analysis of all samples is performed in real time during the exponential phase and obviates the concern that different samples reach the plateau phase at different cycles (13). Until now, the utility of the Light Cycler system in clinical settings has been demonstrated only for a few viral pathogens (1, 3, 11). In the present study, we have evaluated the reliability of the Light Cycler for detection of HCV RNA by comparing the results with those of the widely used, commercially available AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay and an in-house PCR assay (4). Samples with a range of HCV titers were chosen, a procedure that has previously been shown to be useful for validation of HCV PCR methods (9). There were slightly more differences between in-house PCR and the Light Cycler system than between Light Cycler and the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay. This may be partly due to the fact that quantitation of the in-house assay is performed only in full logarithmic steps (4). In contrast, quantitation by both the Light Cycler system and the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay is performed in smaller steps and therefore gives more-precise results. The results obtained by Light Cycler and the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay showed excellent concordance in the vast majority of samples. Spearman rank regression analysis revealed a regression coefficient of 0.83 (P < 0.001). There was no tendency toward continuously higher results in one of the assays, so the differences were most probably due to interassay variations. It has been shown earlier that even with the application of different standardization approaches, interassay variations of PCR methods cannot be excluded (5).

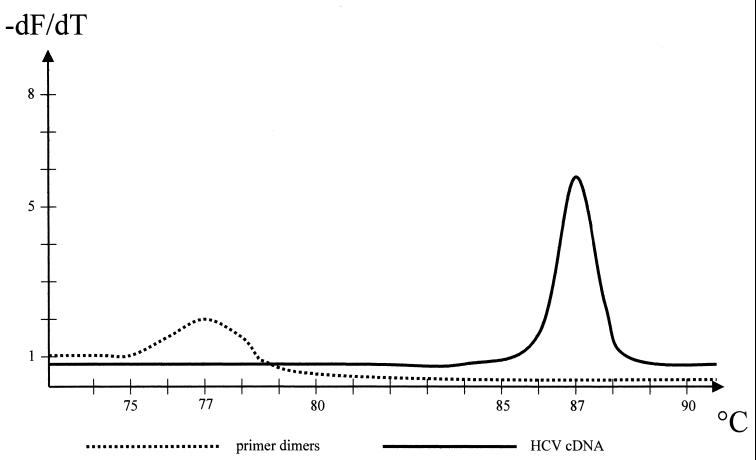

Using Light Cycler, detection of amplification products can be performed by using either SYBR Green or hybridization probes. The hybridization probes consist of two oligonucleotides which are labeled with two different fluorophores. After hybridization the two probes come in close proximity, resulting in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two fluorophores. The emitted fluorescence is measured. In contrast, SYBR Green intercalates between double-stranded DNA molecules. This entails the risk that primer dimers are measured as well as amplified products. Therefore, when SYBR Green is used, a melting-point analysis has to be performed to distinguish amplification products from primer dimers. We designed the primers used in this study in such a way that the melting point of dimers is about 10°C lower than the melting point of specific amplimers, which made the two easy to distinguish (Fig. 2). Both detection formats (SYBR Green and FRET) were tested before the present study was initiated, and they performed equally well, with no significant differences. However, the hybridization probes are much more expensive than SYBR Green, so we used SYBR Green to perform the present study.

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram of a melting-point analysis as accomplished at the end of PCR. Primer dimers have a melting point of 77 to 78°C and are easily distinguishable from HCV amplicons, with a melting point of 87°C. The graph displays the negative first derivative of the melting curve data (−dF/dT) versus temperature.

Our assay revealed a wide dynamic range that extended over a 5-log range of HCV input. One striking advantage of this assay is the speed by which amplification and detection of amplicons are performed. The Light Cycler needs only 15 s for each cycle, including detection. A whole PCR with 45 cycles, including reverse transcription and melting curve analysis, lasts only about 1.5 h. In contrast, PCR by the AMPLICOR HCV Monitor assay or in-house PCR altogether takes about 5 h or 2 days, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cane P A, Cook P, Ratcliffe D, Mutimer D, Pillay D. Use of real-time PCR and fluorimetry to detect lamivudine resistance-associated mutations in hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1600–1608. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choo Q L, Kuo G, Weiner A J, Overby L R, Bradley D W, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espy M J, Uhl J R, Mitchell P S, Thorvilson J N, Svien K A, Wold A D, Smith T F. Diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections in the clinical laboratory by LightCycler PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:795–799. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.795-799.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feucht H H, Zöllner B, Schröter M, Altrogge H, Laufs R. Tear fluid of hepatitis C virus carriers could be infectious. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2202–2203. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2202-2203.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haberhausen G, Pinsl J, Kuhn C C, Markert-Hahn C. Comparative study of different standardization concepts in quantitative competitive reverse transcription-PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:628–633. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.628-633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagiwara H, Hayashi N, Mita E, Takehara T, Kasahara A, Fusamoto H, Kamada T. Quantitative analysis of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum during interferon alpha therapy. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:877–883. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91025-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heid C, Stevens J, Livak K, Williams P M. Real-time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:986–994. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lok A S, Chien D, Choo Q L, Chan T M, Chiu E K, Cheng I K, Houghton M, Kuo G. Antibody response to core, envelope and nonstructural hepatitis C virus antigen: comparison of immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Hepatology. 1993;18:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martell M, Gomez J, Esteban J I, Sauleda S, Quer J, Cabot B, Esteban R, Guardia J. High-throughput real-time reverse transcription-PCR quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:327–332. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.327-332.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, Boyer N, Poliquin M, Degott C, Descombes I, Le Breton V, Milotova V. Pretreatment hepatitis C virus RNA levels and hepatitis C virus genotype are main and independent prognostic factors of sustained response to interferon alpha therapy in chronic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1995;22:1050–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitsche A, Steuer N, Schmidt C A, Landt O, Siegert W. Different real-time PCR formats compared for the quantitative detection of cytomegalovirus DNA. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1932–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira B J G, Milford E L, Kirkman R L, Levey A S. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:454–460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raeymaekers L. Quantitative PCR: theoretical considerations with practical implications. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:582–585. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth W K, Weber M, Seifried E. Feasibility and efficacy of routine PCR screening of blood donations for hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, and HIV-1 in a blood-bank setting. Lancet. 1999;353:359–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schröter M, Feucht H H, Schäfer P, Zöllner B, Laufs R. High percentage of seronegative HCV infections in hemodialysis patients: the need for PCR. Intervirology. 1997;40:277–278. doi: 10.1159/000150558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröter M, Feucht H H, Schäfer P, Zöllner B, Laufs R. Serological determination of HCV subtypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, and 4a by a recombinant immunoblot assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2576–2580. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2576-2580.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittwer C T, Ririe K M, Andrew R V, David D A, Gundry R A, Balis U J. The Light Cycler™: a microvolume multisample fluorimeter with rapid temperature control. BioTechniques. 1997;22:176–181. doi: 10.2144/97221pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]