Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to develop a culturally appropriate, community-based diabetes prevention program, named Little Earth Strong, through partnership with an urban, Indigenous, American Indian community and determine its feasibility in lowering diabetes risks.

Methods:

Using a community-based participatory research, community-level intervention approach, and after conducting a focus groups with key stakeholders (n = 20), a culturally appropriate health intervention was designed across six stages. This included providing nutrition and physical activity individual, family, and group counseling and conducting individual level biometric tests at a monthly Progress Powwow. Community participants (n = 69) included Indigenous individuals ages 18 to 64 years and their families residing in an urban American Indian housing organization.

Results:

Findings included the project’s feasibility, sustainability, and future needs. Lessons learned included the need the need to situate health interventions within Indigenous culture, engage multiple stakeholders, remain flexible and inclusive of all community members, address cultural concerns regarding biometric testing, and focus on specific ages and groups. The outcome variables included qualitative focus group data regarding feasibility and design and quantitative biometric data including hemoglobin A1C levels and weight in which a significant decrease in A1C values were found among women

Conclusions:

Little Earth Strong was both feasible and successful in decreasing A1C levels using a community-level approach, especially in high participators who attended most events. These results demonstrate the promise of diabetes prevention fitness and nutrition interventions that are collaboratively designed with the community.

Keywords: Exercise, Education, Sociology and Social Phenomena, Diabetes Mellitus, Health Services, Indigenous, American Indian, Indigenous, Community-level health interventions, Diabetes Type 2 prevention, culture as prevention

American Indians, or Indigenous peoples, suffer from disparate rates of diabetes in the United States.1,2 Within Minnesota alone, the rate of type II diabetes (T2D) among American Indians has been found 600% higher than for Whites.3 Indigenous persons are further 182% more likely than other Minnesotans to die from T2D.4 Many risk factors contribute to T2D including physical inactivity, poor nutrition and obesity.5 In particular settler colonialism, oppression, trauma, and discrimination in the delivery of health services have been argued to increase T2D risks for Indigenous groups.6,7 Additionally, American Indians at risk for diabetes may experience cultural conflicts with western medicine’s approaches which increase their daily stress.8,9 This daily long-term stress, or toxic stress, can increase vulnerability to poor diet and exercise through both biological and behavioral mechanisms, which may become cyclical.10-14 Individuals experiencing toxic stress, for example, will often have a higher caloric intake due to a greater preference for sugar and fat and lower physical activity.13-15 Given that the harmful effects of stress is cumulative,16 American Indians are particularly susceptible to T2D based on historical trauma, oppression, and experiencing among the highest rates for present life stressors as compared to other racial/ethnic groups.17,18 Thus, health interventions must not only consider diet and exercise but also culturally specific factors that may increase T2D risks.6

T2D/OBESITY PREVENTION AMONG AMERICAN INDIANS

Obesity prevention efforts based on westernized methods have not been as effective as hoped among American Indian populations.19 One reason may be that American Indians do not share the cultural health beliefs of western medicine, resulting in less buy-in and perceived relevance.19 They may also hold more distrust of western practices due to colonial disruption of traditional food practices and restricting access to food, land and spiritual ceremonies.20-23 In contrast, culturally appropriate, comprehensive systemic interventions have successfully decreased rates of T2D among Indigenous groups.23 Designing such health interventions is a complex process because American Indian cultural factors associated with 2TD, and related obesity interventions, are quite varied and vast. There are 574 distinct, federally recognized tribes with more than 200 currently spoken languages.24 The circumstances and specific culture of each tribe are unique. While at the same time, most tribes have experienced historical trauma, economic, education, housing, health and other stressors at levels of severity rarely seen in other American communities.11 Hence, health interventions need to engage tribal communities in health intervention design to account for cultural differences, especially within an urban setting. Furthermore, community programs have been encouraged to develop and test community-level interventions.25 Satterfield and colleagues argued that, “in addition to promoting lifestyle adaptations, population-based approaches as governed by the community can identify and support cultural protective factors in meaningful ways.”26p.2652

This study evolved from a long-term partnership between the first author and the Little Earth of United Tribes, an American Indian Project Based Section 8 housing development. In the neighborhood immediately surrounding Little Earth, 42% live in poverty—nearly twice the rates in communities surrounding all U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development housing.27 Additionally, 17.6% of American Indians in the neighborhood have T2D, the highest rate compared to all other ethnic groups.28 Risk factors further remain high, as almost one-third (32%) of American Indians in the neighborhood are obese—the highest obesity rate in Hennepin County.5 Given that Little Earth residents experience greater social and economic stressors than the general population,27 the community leaders identified and sought to decrease toxic stress, increase culturally connections and supports, and thereby decrease T2D risks. They aimed to co-develop a community level health intervention to halt the rampant spread of T2D in this community, leading Little Earth to partner with the interdisciplinary Indigenous researchers, and allies, to address T2D/obesity health risks.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to develop and examine the feasibility of a culturally appropriate, community-based participatory research (CBPR) T2DM/obesity intervention called Little Earth Strong (LES). Drawing from the Indigenist stress coping model,16 LES sought to modify life stressors by integrating positive coping strategies of exercise and healthy diet through community driven health interventions. We further drew from the CBPR framework29 in engaging key stakeholders in designing the study and implementing and disseminating results. To address T2D at the community level, the effect of colonial and present life traumas on health and environment was also considered. The Indigenist stress coping model provided a framework to examine both trauma risks factors, as well as cultural protective factors, related to Indigenous health and wellbeing.30 Through increasing protective factors such as reconnecting with cultural identity and cultural supports, the model indicates that stressors can be buffered and thereby improve health. Furthermore, programs that utilize multicomponent interventions; such as home, community and school-related interventions, paired with adequate diet and physical activity, have been found to improve outcomes31 and further guided this work. The CBPR framework was used by the authors given it levels the power dynamics between community and researchers by viewing them as co-collaborators and engaging them throughout the process.29

METHODS

Research Design

Through using participatory and educational programming, the Little Earth Strong/LES pilot aimed to cultivate a culturally appropriate diabetes prevention and increase a desire towards fitness within the Little Earth community. During early 2016 the UMN RICH Center and Little Earth program coordinators and advisors sought community input to design a culturally appropriate group health intervention among urban American Indian families residing in a housing development. By engaging key stakeholders in the research design, the partners developed and implemented a full schedule of culturally appropriate group fitness classes, comprehensive evaluation, and goal setting using motivational interviewing.32 RICH and Little Earth collaboratively decided to use both qualitative and quantitative biometric measures as outcomes throughout the following stages.

Stage 1: Initial Focus Groups (Month 1).

After receiving institutional review board approval from the UMN, the focus group was conducted by the program coordinator and research assistant. They consisted of identified key stakeholders—American Indian, Indigenous, adults, age 18 years and older, from the Little Earth community who were interested in improving health. The total number of participants fluctuated between 17 and 20 during the session. After consenting, participants were asked to discuss their views on fitness and nutrition within the community. Sample questions included What would a healthy program look like? What activities would you like to see and where? These focus groups also led to the formulation of a Community Advisory Board (CAB) featuring five elders within the community who were regarded as knowledge keepers. These elders included two self-identifying females, two males, and one Two-spirit individual who met on a monthly basis to streamline the focus of the programming. With their guidance the LES program was developed by building from existing community strengths and resources. CAB elders co-led decisions related to the process of informed consent, recruitment strategies, research methods, implementation of study procedure, language used to inform and engage the community participants such as flyers, interpretation, validation and dissemination of both qualitative and quantitative findings. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed. Field notes were collected during these meetings and thematically analyzed.

Stage 2: The Enrollment Sessions (Month 2).

Following the focus groups, the program coordinator held four enrollment sessions for interested adult Little Earth community members (age 18 years and older; n = 69). Validated by the CAB, the researchers conducted recruitment by presenting a Power Point presentation and distributing a brochure onsite. The CAB further guided the inclusion criteria which included being a resident of Little Earth, adult, American Indian and at risk for T2D. Risk factors for diabetes were determined through the Diabetes Risk Test by the American Diabetic Association where a score of 5 or higher were considered at risk.1 Exclusion criteria included being unable to be active and participate in the project due to other conditions. The CAB further suggested including interested participants’ children, ages 5 years and older to attend the health fairs and classes though no biometric measures were taken. After consenting and joining the study, adult participants received a free t-shirt and $15 Target gift card. At this time, participants were also asked to complete an initial survey regarding their current fitness and nutrition status and identify goals to guide their motivational interviewing sessions.

Stage 3: The Initial Physical Examination (Month 2).

Forty of the 69 participants consented into the study and underwent a physical examination by an onsite MD, free of charge in order to participate in fitness classes. The residents had an option to see their own MD if they preferred. After the physical examination, members of the Minnesota Student Pharmacy Alliance helped to take initial weight and A1C blood glucose measurements. Exclusion criteria included those who were not deemed physically able to participate.

Stage 4: The Fitness Classes (Months 3 to 15).

For 12 months, seven weekly group fitness classes were offered onsite at Little Earth with schedules being distributed weekly to participants. Fitness instructors were contracted from the local YMCA or were volunteers from the community. Each participant’s attendance was recorded at each fitness classes (using participant number).

Stage 5: The Monthly Progress Pow Wow (Months 3 to 15).

Throughout the duration of the study, monthly fitness check-in events called, “Progress Pow Wows” were held, as overseen by the CAB. Pow wows are cultural events that include Indigenous social dances and are often open to the public to participate. Participants as well as any member of the community could participate in the Indigenous powwow dancing. During the monthly powwow, each participant’s weight and A1C (3-month blood glucose measurements) were taken. A licensed pharmacist or MD preceptor was present and delivered health education to all community members. Further, participants received their monthly $15 Target gift card for their ongoing participation. During the pow wow participants also received fitness gear (water bottle, sweat-bands, tennis shoes, etc.) for attending a certain number of fitness classes according to the following point system (see Appendix A Figure 1, 2 and Table 1). Participants were further served healthy foods during the feast, or community dinner, to expose them and their family to nutritious foods in a community setting. The Minnesota Pharmacy Student Alliance further provided nine health booths to educate participants on various health and wellness topics, at most of the Progress Pow Wow events.

Table 1.

Point Based System Structure for Little Earth Strong Participants

| Benchmark | Points Awarded |

|---|---|

| Attending 1 class | 1 |

| Attending Progress Pow Wow | 1 |

| Monthly Health Goal Reached | 4 |

| Attending 10 classes/month | 15 (5 bonus points) |

| Point Total | Prize |

| 5 | Water bottle |

| 10 | Nike wristband |

| 20 | Nike or Jordan athletic shorts |

| 30 | Free weights or jump rope |

| 45 | Football or basketball |

| 70 | Headphones |

| 100 | Nike N7 (Native) Shoes |

Stage 6: Post Intervention Focus Group (Month 24).

A second wave of focus groups were conducted by the research team with the CAB and other key stakeholders including LES program managers as well as previous participants, who all actively participated until the study’s completion. Overall participation included 15 individuals with 2 having to leave during the focus group. Sample questions included What went well in the program? What could have been done better? What were some of the long-term impact of the program? Field notes were collected during these meetings and thematically analyzed. The focus groups were also audio recorded and transcribed.

Qualitative Analysis and Sample Size Determination

The focus group feedback was coded and themed through research team group consensus. This team featured two Indigenous and one ally research scientist, an Indigenous project research assistant, and two Indigenous community members who used a qualitative descriptive content analysis33 to analyze participant findings from both pre and post intervention. The research assistant then compared the coding for each and shared differences and overlaps with the collective research team. Differences were resolved through discussion and group consensus. Data saturation was reached during analysis of the third focus group transcript for both the initial and program evaluation focus groups as indicated by a repetition of codes, yet the following focus groups were also reviewed by the research team for final validation.34 Researchers met with the CAB to present the themes, discuss, and interpret the qualitative results during two separate community group meetings with approximately 10 participants. The initial themes did not vary based on community feedback, and the community affirmed the accuracy of the findings.

RESULTS

Focus Groups

First in our pre and post intervention focus groups, we found that a community, multilevel intervention was desirable and feasible. Through six stages, this intervention targeted the individual, family, and community in identifying and developing activities that would facilitate health. It further brought together many community partners from the fitness leaders who leveraged resources to offer exercise classes to the University students, trainees and even traditional healers who attended and provided community level services at the Progress pow wows. Furthermore, the community resident associations staff and educators began to utilize other funding to feed into the LES project. For instance, the afterschool program assisted youth in making powwow regalia (i.e., clothing appropriate for social dances) and also in instructing them to dance, which increased their exercise levels. This study innovatively engaged community leaders post 24 months of the research intervention to determine long-term effects and lessons learned. The thematic analysis of focus group revealed several themes including feasibility in fostering an Indigenous culture of health, sustained impact, and future needs as follows.

Feasibility in Fostering an Indigenous Culture of Health

Themes emerged from the focus group discussions surrounding the feasibility of developing and supporting a culture of health by bridging multiple key stakeholders who could support an Indigenous culture of health at Little Earth.

LES was special in way that it got the elders going, brought the youth in and it slowly became a program where the whole family would come in at once. It just started going and going. It was nice to see our community embrace something that was about health and wellness because too many times people go, they get a gift card and they don’t learn anything. They don’t want to learn anything. The project was special because it started separately then it ended up being family. It shows how special it was.” [Little Earth Youth Leader]

A second related finding was that the community desired cultural healthy activities that increased cultural identity, pride and supportive interpersonal relationships; i.e., pow wows and feasts. Altogether these initiatives organically facilitated the multigenerational familial engagement in the program. The CAB and community members believed that being flexible and inclusive in the program curriculum was key, which was highlighted as one of the most influential factors driving the program’s impact. Further community elders felt that allowing children and grandchildren to participate in programming alongside their caregivers bolstered active participation of community members.

I really enjoyed that program because not only it focused on cultural stuff, but the biggest cultural aspect was it focused on the family. It was not just the kids; it was not just the parents—it did not matter if one person was fat in your family or if they were healthy or skinny. It did not matter if one had diabetes and no one else did and they focused on everybody within the family. To me that is cultural because when you want to do something, you’ve got to include the whole family. By doing that it made you want to part of it more, try harder and learn things. [Community Organizer and former Executive Director]

A third finding related to facilitating an Indigenous culture of health was the need to decolonize food and exercise approaches. In particular, they wanted the research team to be mindful of this during nutrition counselling.

When western practitioners tell you to stop eating Indian Taco and Fry Bread, they don’t realize that that’s what our people had to do to survive. Indian Tacos weren’t part of our life … until they put us on reservations and gave us commodities and our people had to figure out what to do with them. The program people told us that your fry bread is not bad food. It’s just you cannot eat it every day. Not making us feel bad because of the relationship we share with our food. It helped us survive genocide. One you do that it makes us feel bad. [CAB Elder]

Sustained Impact

The trauma-informed nutrition education and ongoing progress pow wows continue to have sustained impact on participants’ health behavior. The programming also took into account the impact of multigenerational poverty on food access, which was appreciated.

Also, understanding that coming in here and telling us to buy healthy food was not going to work really helped me with this program … They [research team] looked for ways to accommodate our needs and did not make us feel bad about the food you eat because we have to eat. They showed us how to make my Mac N’Cheese healthier by using unsalted canned tomatoes, by using natural. That’s what I liked about it that they thought outside the box, meeting us at where we are at. [Grandparent]

Using a community-level approach, which included engaging children in regalia making and after school activities to offering healthy community feasts during the progress powwows, the participants reported that sustainability of the pow wows, healthy foods, and exercise was possible, especially as healthy norms were communally developed.

Future Needs

Several future needs were identified. Our findings indicated that an onsite health intervention was key to gaining participation and needed for sustained impact. In particular the post focus groups findings revealed that health policies were necessary to tackle issues such as vending machines. Community situated vending machines fulfill a critical need for food access, with elders appreciating the convenience. However, participant feedback during the nutrition counselling indicated that vending machine foods contributed to ingesting “junk foods” and may have long-term health implications. Following the study, participants reported an overall decrease in consumption/purchase of sugary and unhealthy snacks after they created a policy that one vending machine must offer healthier foods.

We’ve got two vending machines now because we have one healthy one at LERA and another unhealthy one. The Pepsi machine offers all the sugary beverage and the coke machine has Gatorade in it. It has water, tea and coke. I know it’s kind of crazy but since they put the coke one in, the coke one sells more which includes the water, the Gatorade etc. So, if it’s there people will buy it, and they will avoid the sugary ones. [Elder]

Our post-intervention findings further found that the intervention has stimulated community-wide engagement. In particular, community dialogue on farming and urban food was stimulated, especially given the rising cost of healthy food and vegetables and intergenerational poverty at Little Earth. While the LES intervention developed a health advisory board, LES Health Advisory Council (LESHAC), LESHAC was sustained post-intervention and continues to guide health decisions at Little Earth today. LESHAC specifically advises community members who are actively building community-wide programming to promote healthy diet and exercise.

The women’s group is still continuing what the program started. Last year they did a cooking contest using the ingredients from the farm. One guy across the farm made potato chips out of the farm and everybody was like—how did you do it because I love to make it. So, making it fun, keeping it in your face kind of where they can reach for it if they want. A lot of people at times would get on the Facebook page of the community and ask about different healthy recipes now … It would not have happened without this project. [Elder]

LESSONS FOR RESEARCHERS AND PROVIDERS

Focus groups revealed the need for providers to cater to the health needs of all participants onsite, including elders. Furthermore, participants identified the value of engaging multiple stakeholders who could coordinate a community-level intervention. However, at the same time, while many participants engaged in biometric data. The community members felt that the coordination of biometric testing services did not take into account long waiting times to get tested, leading to attrition rates.

One thing that irritated the elders and some adults was that it was the line to sit out there and wait to get your A1C. They only let a couple of people in because of confidentiality, HIPAA etcetera. They gotta figure out a better way to do that. They had us all coming in at the same time and it was like—Oh My Goodness! There is a huge line. Many elders also got disabilities; you know so allowing these elders to go first who are also caregivers of many children would be ideal.

Finally, the participants expressed the need to consider specific age groups and populations, as well as specific health education. While the program was successful in facilitating multigenerational engagement, the community members felt the need for more youth engagement.

One thing I’d like them to do is engage our young parents. For example, I told them show me how to cook healthier food using what I have available. But if you take a young parent and show them the same, you can make that whole generation healthy by teaching that parent how to feed that baby correctly, by not shaming her. … So really a parenting program that is non-judgmental. [Elder]

The community members further placed an overwhelming emphasis on the need for strength-based nutrition education, as they still face barriers to culturally responsive nutrition education within the local health systems. This highlights the critical need to disseminate the study findings to change current practice standards in nutrition education, especially around body mass index (BMI) and obesity reporting.

With them charts come fat shaming. When you see them and you look at your BMI and it says you are obese, you’re like holy shit!! We gotta make it strength-based which doesn’t make people feel bad. Your physical appearance doesn’t indicate your wellbeing and nutrition. I think the western practitioners should listen and answer questions and be concerned … If they listen better and talk less and practice active listening. [Elder]

Post Intervention Biometric Data Findings.

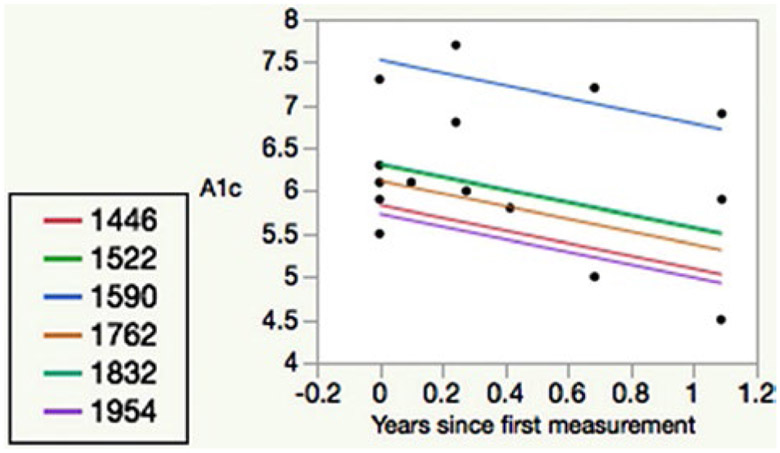

Though only comprising a small portion of the study, LES further found that biometric testing was feasible and initial health results were promising, especially among women and those who attended more events (see appendix A Figures 1 and 2 for further information). These preliminary results indicate that frequently offering activities within the community may be most beneficial.

DISCUSSION

LES is a co-developed a community-level, culturally appropriate health intervention designed to prevent T2D. While many American Indian, or Indigenous, health interventions have culturally adapted empirically supported treatments; they have often not been situated within cultural context of the community,6,35 as with the LES pilot. Our findings support prior research that complementary western treatment, including motivational interviewing,29,36,37 can be used effectively if Indigenous cultural health frameworks are considered and privileged. Focus group findings attested to the long-term impact of the program in community, family, and individual level food and exercise behavior, as well as the biometric data (see Appendix A Figure 1, 2). The community created a healthier culture and continued the onsite progress powwows, beyond the pilot project. Overall, LES was feasible, seemingly sustainable, and has large implications for health intervention design, researchers and providers.

Implications

Our findings have several implications for T2D prevention health intervention design. First our findings support multilevel, interpersonal, community, and systemic approaches, which are particularly important for diabetes prevention.6,13,35,38,39 Too often individual-level interventions are implemented that do not produce sustainable results, as they ignore one’s lived context.19 Interventions that situate themselves within culture can guide treatment and provide meaningful results. For instance, as our findings suggest, Indigenous individuals who have received nutrition counseling may find that they do not have access to healthier food items and are unable to make the lifestyle choices suggested. Thus, an individual’s cultural and lived environment should be considered in program design.

Our finding further imply that Indigenous cultural practices can serve as positive coping resources for health interventions, similar to findings in other T2D research.39 Cultural activities that increase cultural identity, in particular, have been found to increase healthy lifestyle behaviors.7,40-42 However urban American Indian communities may have vastly different specific cultural practices, which make designing appropriate health interventions challenging.43 Thus given the LES intertribal community context, we centered our intervention not on a specific tribal activity, dance, or belief but instead on common cultural activities, or pan-Indian activities, such as pow wow dancing and feasts. In particular, pow wow dancing serves a common function of increasing cultural identity, increasing healthy leisure time activity, and increasing community interaction, or relationships among American Indians from distinct tribal backgrounds and languages. Thus, we found that centering health interventions around pow wows is culturally appropriate and can facilitate increased exercise, community involvement, and socially building cultures of health, which may be applicable to other Indigenous groups.

In regard to diabetes researchers and healthcare providers/educators, our findings imply that they may need to consider the historical and cultural context of both food and physical activity in health interventions. Indigenous food culture has seen drastic changes as a result of European colonization. For hundreds of years, Indigenous peoples were abruptly prevented access to their traditional foods and practices, either directly or through removal from their homelands.44,45 The authors refer to this as food colonization, the intentional colonization of food by the U.S. government to erode Indigenous culture and identity. During such, Indigenous communities were forced to survive on unhealthy alternatives; e.g., government commodities and fast-food.46 As is typical across generations, offspring often prefer the food that their parents eat or were given. Hence many Indigenous persons, particularly among the youth, have begun valuing unhealthy foods (e.g., fry bread, commodity cheese, bologna, etc.) as opposed to healthy, original foods (e.g., corns, beans, squash, lean meats, etc.).22 However our results indicate that healthy foods can become valued if the community offers healthy traditional food choices and activities while creating healthy food norms. Therefore, a need exists to move health interventions from the clinic to the community, such as with community feasts that can provided exposure to healthy foods.

Furthermore, Indigenous views of relationships, or relationality; i.e., experiencing self as part of a larger context to others- past, present, and future, is often central to healing and health.47,48 Thus, our health intervention emphasized creating a context to support healthy relationships within the community. This was accomplished by sharing food, providing community based opportunities for group exercise, and pow wow dancing. This varied from other western models, which often focus solely on the individual. Our study underscores that healthcare providers and educators need to simultaneously consider the cultural changes within the community, and, or how macro-level interactions impact the individual’s access to food and leisure time activity across multiple generations.

COMMUNITY PERCEPTIONS OF LESSONS LEARNED

The community co-authors identified several lessons learned that have implications for both research and practice. First, researchers and practitioners often ignore the influence that colonization has had on food choices, food perceptions, and activity levels.26 Hence, the community should be in control and fully involved to identify solutions that may work, as well as exercise their health sovereignty that may facilitate sustained health changes (see Jennings et al.45). For instance hunting and gathering food practices that include ceremonies and extensive protocol often require high levels of physical activity, which are less practiced today, especially in urban settings.49 However, health interventions that include the community in reinvigorating and revitalizing these original healthy practices may result in more community buy-in,49 as supported by our study findings. Additionally, infrastructure can be developed to sustain the program, such as with the LESHAC, which was developed as result of this project and continues to advise on many health-related initiatives in the community.

Given American Indians have reported that eating healthy may result in being ostracized at the store, or in the community,50 addressing cultural perceptions of healthy foods is critical. Asking American Indian individuals to eat healthy may also be asking them to forego foods that are associated with their cultural identity/community and may not always be well received. Similarly, when providers recommend more individualized exercise and discuss BMI, these concepts may not be culturally congruent, as based on our findings. For many American Indian cultures, junk foods (i.e., foods with low nutritional value and high calories) may have become an indicator for Indigenous cultural identity, such as with fry bread, or fried dough that resulted from government rations.50 Thus, by asking someone to cease eating certain junk foods, the diabetes educator/provider may be seen as asking the patient to not eat their cultural foods. Our findings suggest that a community-level, culturally relevant approach, as led by the community, may be most appropriate to decolonize health approaches and improve health.

Community Views of Limitations

Despite determining feasibility and potential for success, several limitations were noted during this pilot project, as highlighted by the community. First, future LES programming could benefit from improving how biometric data is collected. This includes being more open to seeing multiple family members at once, and assuring that elders are seen first, as opposed to having to wait. Also, there may be other biometric data that is more valuable to the community than A1C data and BMIs; for example, other biometric levels of health, food perceptions, and dietary changes appeared more important to the community. Secondly, while high attrition rates and sporadic attendance were expected—given the stressors in this low-income community, the children from all 40 families remained active and involved throughout the program, indicating the need and increased feasibility for a child-focused intervention. Our post intervention focus group further indicated the need for more elder-friendly program implementation and engagement of younger parents. Third, there exists a need for formalizing the health intervention and measuring more outcome variables than biometric indices alone, such as cultural and psychosocial indices.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, we found that a culturally appropriate, CBPR intervention has potential to increase leisure time physical activity and healthy diets in an urban American Indian community. This work in progress is one of the first pilot studies to culturally situate a health intervention while targeting the community, family, and individuals in an urban Indigenous housing community. To eliminate T2D disparities, diabetes educators, researchers and other providers must work in partnership with the community to co-develop innovate unique models of care. Promise may lie in centering diabetes interventions around common cultural activities within Indigenous communities, offering multiple community based options, as well as considering the cultural roles of food and physical activity through a decolonizing lens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Little Earth Strong was funded by grants from the Notah Begay III Foundation and Nike N7 Fund. It was further supported in part by the National Institute of Health LRP funding for Dr. Johnson-Jennings. The authors are grateful to the Little Earth Community for their participation in the design and implementation of the Little Earth Strong Diabetes Prevention Program.

APPENDIX A

A1C Measures (Adults)

Per biometric measures, baseline A1C measures were obtained for 40 adult participants (maximum >13; minimum 4.9) (Figure 1). Forty-three percent fell in the normal range (<5.6), 35% in the prediabetes range (5.7–6.4) and 23% in the diabetic range (>6.5); information was not available to determine if some of these participants still met treatment goals that could have been previously established by their healthcare provider. We had substantial attrition with only ten of the initial 30 adults and their families completing the entire program. However, many of the 30 families still sporadically attended the progress powwow and feasts. Even though, we found significant results for completing females who had a 0.80% decrease in A1C over the course of the program (n = 6, p = 0.005), and completing males had a 0.07% decrease in A1C (n = 4, p = 0.84). Note that A1C was not measured in children.

Statistical Analyses

We further analyzed the biometric data; i.e., weight and A1C results using mixed linear models and the restricted likelihood method using JMP (v. 12 Pro; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC). Independent random effects were person (i.e., intercept) and the slope in time since the first measurement. Fixed effects were sex and age group (adult vs. child) for the weight outcome and sex for the A1C outcome.

Subgroup Analysis

We then conducted a subgroup analysis among the participants who were classified as high fitness class participators (75% quartile and above) (Figure 2). The number of participants included in this analysis was six, and there were 16 A1C measurements. We found that attending at least 24.5 classes resulted in 100% of participants having a decline in A1C. This sub analysis included the trend in time since baseline, including the random effects for intercept and slope. The A1C declined at an average rate of 0.74% per year (standard error 0.32, p = 0.040).

Figure 1.

Adult baseline A1C data for Little Earth Strong participants.

Figure 2.

A1C subgroup analysis (high participators) for Little Earth Strong Diabetes Prevention Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial interests in any product or service mentioned in this article, including grants, employment, gifts, stock holdings, or honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Prevention (CDC). National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Service; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indian Health Service. Diabetes in American Indians and Alaska Natives: Facts at-a-glance [updated 2012]. www.ihs.gov/MedicalPrograms/Diabetes/HomeDocs/Resources/FactSheets/Fact_sheet_AIAN_508c.pdf

- 3.Minnesota Department of Health. Health disparities by racial/ethnic populations in Minnesota. St. Paul (MN): Center for Health statistics, Division of Health Policy; 2009. www.health.state.mn.us/data/mchs/pubs/raceethn/rankingbyratio20032007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.SHAPE 2010 Adult Data Book. Minneapolis: Minnesota Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millar K, Dean HJ. Developmental origins of type 2 diabetes in Aboriginal youth in Canada: It is more than diet and exercise. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:127452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders Thompson VL, Johnson-Jennings M, Bauman AA, Proctor E. Use of culturally focused theoretical frameworks for adapting diabetes prevention programs: A qualitative review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satterfield D, DeBruyn L, Santos M, Alonso L. Health promotion and diabetes prevention in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities Traditional Foods Project, 2008–2014. MMWR Suppl. 2016;65(4):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson-Jennings M, Walters K, Little M. And [they] even followed her into the hospital: Primary care providers’ attitudes toward referral for Traditional Healing Practices and integrating care for Indigenous patients. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;29(4):354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marley TL, Metzger MW. A longitudinal study of structural risk factors for obesity and diabetes among American Indian young adults, 1994–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Story M, Evans M, Fabsitz RR, Clay TE, Rock BH, Broussard B. The epidemic of obesity in American Indian communities and the need for childhood obesity-prevention programs. American J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4):747S–54S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpern P. Obesity and American Indians/Alaska Natives. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teufel-Shone NI, Jiang L, Beals J, et al. Demographic characteristics and food choices of participants in the Special Diabetes Program for American Indians Diabetes Prevention Demonstration Project. Ethn Health. 2015;20(4):327–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satter DE, Seals BF, Chia YJ, Gatchell M, Burhansstipanov L. American Indians and Alaska Natives in California: women’s cancer screening and results. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(1 Suppl):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11-12):887–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “Indigenist” stress-coping model. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):520–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian Reservation populations. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:851–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eitle TM, Eitle D, Johnson-Jennings M. General strain theory and substance use among American Indian Adolescents. Race Justice. 2013;3(1):3–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams AK, Harvey H, Brown D. Constructs of health and environment inform child obesity prevention in American Indian communities. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(2):311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson JL, Allen P, Helitzer DL, et al. Reducing diabetes risk in American Indian women. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai G, Derrington S, Kolo S. Considerations in the treatment of American Indian/Alaska Native patients with diabetes mellitus. www.cecity.com/aoa/healthwatch/jan_11/print2.pdf 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings D, Lowe J. Photovoice: Giving voice to Indigenous Youth. Pimatisiwin. 2014;11(3):521–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang L, Manson SM, Beals J, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Results from the Special Diabetes Program for Indians Diabetes Prevention demonstration project. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2027–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IHS. Newsroom: Disparities—Indian Health Service (IHS) [updated 2013; cited 2016 May 6]. www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/

- 25.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the diabetes prevention program into the community: The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satterfield D, Volansky M, Caspersen C, et al. Community-based lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little Earth Residents Association. Little Earth of United Tribes Inc. History; [updated 2017; cited 2017 Feb]. www.littleearth.org/about-us/history/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department. HCPH. Metro SHAPE 2006 Hennepin County disparities data book. Minneapolis: Minnesota Statewide Health Improvement Program; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Incorporating culture in an “Indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Rep 2002;117:S104–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, Wilson R, Wang Y. Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52:1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castro FG, Shaibi GQ, Boehm-Smith E. Ecodevelopmental contexts for preventing type 2 diabetes in Latino and other racial/ethnic minority populations. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):89–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walters KL, Levy RL, Pearson C, et al. ; Project hәli?dx(w) Intervention Team. Project hәli?dx(w)/Healthy Hearts Across Generations: Development and evaluation design of a tribally based cardiovascular disease prevention intervention for American Indian families. J Prim Prev. 2012. Aug;33(4):197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walters KL, Johnson-Jennings M, Stroud S, et al. Growing from our roots: Strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Communities. Prev Sci. 2018. Jan;21(Suppl 1):54–64. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z. PMID: 30397737; PMCID: PMC6502697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jobe JB, Adams AK, Henderson JA, Karanja N, Lee ET, Walters KL. Community-responsive interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in American Indians. J Prim Prev. 2012;33(4):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Indian Health Service. Special Diabetes Program for American Indians 2011 Report to Congress: Making progress toward a healthier future. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schell LM, Gallo MV. Overweight and obesity among North American Indian infants, children, and youth. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24(3):302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodge FS, Pasqua A, Marquez CA, Geishirt-Cantrell B. Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(1):6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macaulay AC, Paradis G, Potvin L, et al. The Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project: Intervention, evaluation, and baseline results of a diabetes primary prevention program with a native community in Canada. Prev Med. 1997;26(6):779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman H, Wampold B. Challenges to the development of culturally relevant, empirically supported treatment. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agans JP, Champine RB, DeSouza LM, Mueller MK, Johnson SK, Lerner RM. Activity involvement as an ecological asset: profiles of participation and youth outcomes. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(6):919–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jennings D, Little M, Johnson-Jennings M. Developing a Tribal Health Sovereignty Model for obesity prevention as guided by photovoice. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2019;12(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy B. Diabetes and identity: Changes in the food habits of the Innu a critical look at health professionals’ interventions regarding diet. In: Lang MLFGC, editor. Indigenous peoples and diabetes: Community empowerment and wellness. Durham (NC): Carolina Academic Press; 2006:167–86. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson-Jennings M, Jennings D, Little M. Indigenous data sovereignty in action: The Food Wisdom Repository. J Indig Wellbeing. 2020;4(1). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson-Jennings M, Paul K, Olson D, LaBeau M, Jennings D. Ode’imin Giizis: Proposing and piloting gardening as an Indigenous childhood health intervention. J Health Care Underserv. 2020;31(2):871–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satterfield D, DeBruyn L, Santos M, Alonso L. Health promotion and diabetes prevention in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities: A Traditional Foods Project. MMWR Suppl. 2016;65(4):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy B. Diabetes and identity: Changes in the food habits of the Innu a critical look at health professionals’ interventions regarding diet. In: Ferriera ML, Lang GC, editors. Indigenous Peoples and Diabetes: Community empowerment and wellness. Durham (NC): Carolina Academic Press. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]