ABSTRACT

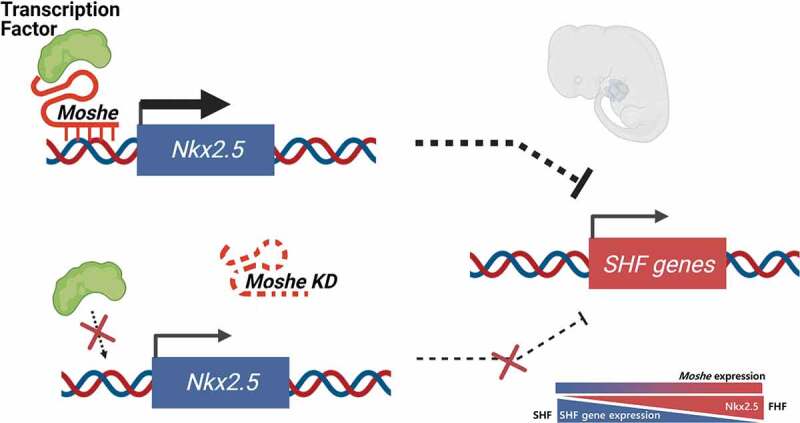

The roles of long non-coding RNA (LncRNA) have been highlighted in various development processes including congenital heart defects (CHD). Here, we characterized the molecular function of LncRNA, Moshe (1010001N08ik-203), one of the Gata6 antisense transcripts located upstream of Gata6, which is involved in both heart development and the most common type of congenital heart defect, atrial septal defect (ASD). During mouse embryonic development, Moshe was first detected during the cardiac mesoderm stage (E8.5 to E9.5) where Gata6 is expressed and continues to increase at the atrioventricular septum (E12.5), which is involved in ASD. Functionally, the knock-down of Moshe during cardiogenesis caused significant repression of Nkx2.5 in cardiac progenitor stages and resulted in the increase in major SHF lineage genes, such as cardiac transcriptional factors (Isl1, Hand2, Tbx2), endothelial-specific genes (Cd31, Flk1, Tie1, vWF), a smooth muscle actin (a-Sma) and sinoatrial node-specific genes (Shox2, Tbx18). Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification showed Moshe activates Nkx2.5 gene expression via direct binding to its promoter region. Of note, Moshe was conserved across species, including human, pig and mouse. Altogether, this study suggests that Moshe is a heart-enriched lncRNA that controls a sophisticated network of cardiogenesis by repressing genes in SHF via Nkx2.5 during cardiac development and may play an important role in ASD.

KEYWORDS: Long non-coding RNA, Gata6 antisense transcript, heart development, atrial septal defect, second heart field

Introduction

The heart is the first functional organ and is critical for embryonic survival [1]. To perform its vital function as a pump, the heart consists of diverse origins of cell types that contribute to its different regions. Cardiac cell-type segregation is regulated in a spatiotemporal manner. Recent studies have revealed that two distinct sources of myocardial progenitor cells (first- and second-heart fields) are involved in early cardiogenesis. The first heart field (FHF) refers specifically to the first wave of mesodermal cells that differentiate into only cardiomyocytes to form the primitive heart tube and that express muscle-specific proteins. Instead, the secondary heart field (SHF) was found to lie posteriorly and medially to the FHF within the pharyngeal mesoderm and consists of not only cardiomyocytes but also endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells [2].

Sophisticated coordination of cardiac gene networks is important for the proper development of the heart. Nkx2.5 and Isl1 are the most well-known transcriptional factors that act as lineage bifurcation regulators. Interestingly, FHF lineage cells express Nkx2.5 but not Isl1 [3]. Despite their co-expression in SHF, Nkx2.5 represses Isl1 expression to control the subtype identity [4]. Single RNA seq studies show that the higher the expression of Nkx2.5 and the lower that of Isl1, the higher the rate of differentiation into endothelial cells rather than cardiac muscle cells [3]. Therefore, whereas FHF mainly differentiates into myocardial cells, SHF displays retarded differentiation into cardiomyocytes and shows multipotent characteristics of cardiac mesoderm and cardiac progenitor cells, which finally diverges into various lineages.

Recent studies using high-throughput sequencing technology have revealed that the dysregulation of sensitive gene networks and signalling pathways is the leading cause of congenital heart diseases (CHDs) such as atrial septal defect (ASD), which can cause infant morbidity and child mortality and is the most common type of birth defect [5]. However, the mechanisms of gene networks in a distinct spatial and temporal manner of cardiac development remain largely unknown. Also, gene regulatory networks have been expanded from protein-coding genes to include transcription factors to non-coding transcripts, including long- and short non-coding RNA categorized by size. Notably, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), defined as non-coding RNAs longer than >200 nt, has been highlighted due to their tissue-specific characteristics. Hundreds of thousands of lncRNAs were identified from various species and tissues, and their roles in cardiac development and disease processes have been demonstrated in a few lncRNAs. Several lncRNAs such as Fendrr, Braveheart (Bvht), Linc1405 and Upperhand have been identified as lncRNA linked to cardiac development [6,7]. Despite all the efforts to find the lncRNA involved in heart development, only a handful of lncRNAs have been characterized regarding their functions as important cis and trans-acting modulators for the expression of protein-coding genes that are functionally relevant to cardiac development.

Here, we identified a lncRNA 1010001N08Rik-203, one of the isoforms of the Gata6 antisense transcripts, which we named as Moshe (MOdulating Second HEart field progenitor) and revealed its putative functions in cardiac development via SHF gene network by modulating Nkx2.5. Our work shows not only pathways regulating heart development but also potential mechanisms by which dysfunction may affect congenital heart diseases, such as ASD.

Materials & methods

DATA acquisition and analysis

RNA expression data publicly opened by Wang, W., et al. [8] and Wamstad, J.A., et al. [9] were used for hierarchical clustering.

Gene expression and differential gene analysis

The FPKM (Fragments Per Kilo base of exon per Million fragments mapped) data of ESC, mesoderm, cardiac precursor, and cardiomyocyte cells were obtained from previous studies [9]. Generation of heatmap and clustering of genes were performed with ‘pheatmap’, the R-package using hierarchical clustering with the ward.D2 method. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of DEGs was performed with the Euclidean method. The intensity of gene expression was log2 transformed and Z-score normalized.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis

GO enrichment analysis was used to examine the major function of DEGs according to Gene Ontology, which is the central functional classification of NCBI. GO analysis in the biological process library of DEGs was executed with the DAVID gene annotation tool. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test to select biological processes. Significant biological processes were identified by p-value <0.05.

Mouse and human cell differentiation to cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocyte differentiation was performed by the following method previously published by Jeong et al. [10]. In brief, 3 × 105 P19 EC (ATCC CRL-1825™) cells were cultured in 60 mm bacterial grade petri dishes in the presence of 0.8% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) for embryonic body formation for 4 days and transferred to mammalian cell culture dishes. The medium was changed every 2 days until day 8. Human ESC cells differentiated into cardiomyocyte for 31-day differentiation process were kindly provided by E.Y. Kim from the Institute of Reparative Medicine and Population, Medical Research Center, Korea [11], and for a 10-day differentiation process were kindly provided by M.Y. Lee from Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyungpook National University, Korea [12].

Moshe knockdown by LNA

Locked nucleic acid (LNA) modified antisense oligonucleotides were designed for Moshe by GapmeRs (50 nM; Exiqon). 50 nM LNA for anti-Moshe was transfected to P19 cell lines using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Life Technologies) for 24 hours. After 24 hours media was changed. LNA sequences were listed in Supplementary Table 3.

5ʹ- and 3ʹ-rapid amplification of cDNA ends

Rapid amplification of cDNA-ends was performed according to the Gene Racer Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was isolated from ICR E9.5 embryos, and 1 μg of total RNA template was used alongside the GeneRacer primer (supplied) and a gene-specific primer (GSP) listed in Supplementary Table 1. Primary and nested PCR reactions were performed using GOTaq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Amplicons were cloned into pGEM T Easy Vector systems for Sanger sequencing (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was obtained from P19, hESC, adult tissues of mouse and pig by using TRIZOL reagent (ThermoFisher, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed on 1 μg total RNA by using the 5X All In One Master mix kit (ABM, New York, USA). The synthesized reaction was performed at 42°C, 50 min and 85°C, 5 min. qRT-PCR was carried out using SYBR green (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The following cycling conditions were used: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, then 45 cycles of 95°C for 15s, and 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min followed by a dissociation curve. Hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS) was used as a reference gene. Primers used in this study were described in Supplementary Table 2. All qRT-PCR was performed in technical triplicates. The animal experiments and in vitro cell differentiation analysis were performed on biological triplicates, and LNA knockdown experiments were confirmed more than twice. Expression data were calculated using delta-delta CT and visualized using both biological and technical replicates (n = 3). Mouse isoform expression was graphed by delta-CT since no other isoforms were detected.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

DIG-labelled in situ probes were generated by in vitro transcription with SP6 or T7 polymerases using DIG RNA Labelling kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). E8.5, E9.5 and E12.5 embryos were hybridized with a DIG-labelled 1010001N08Rik or Gata6 antisense probe at 70°C overnight. After hybridization, embryos were incubated in 1.5 μl-3 μl anti-DIG antibody (Roche) at 4°C overnight. In the end, the embryos were washed in PBST, and the signal was detected using BM purple (E8.5 and E9.5) and NBT/BCIP as the chromogenic substrate (E12.5). E12.5 embryonic hearts were subjected to paraffin wax embedding after 4% PFA fixation and dehydrated through a graded ethanol procedure. We also perform benzyl benzoate/benzyl alcohol clearing steps on E12.5 embryonic hearts after whole mount in situ hybridization.

Immunocytochemistry

D-2 and D-6 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min at room temperature. After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocking with 2% BSA. Primary antibodies were diluted with 1:250, overnight at 4°C. Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse antibody diluted with 1:500 was used as secondary antibody. Images were analysed with an LSM-510 META confocal microscope system (Carl Zeiss). Primary antibodies for α – Actinin (sigma-Aldrich), cardiac troponin T (cTnT, Abcam) and Nkx2.5 (Abcam) were used in this study.

Chromatin isolation by RNA purification

ChIRP assay was performed by following the protocol previously published [13]. Briefly, six biotinylated antisense (AS) oligonucleotides (20-mer) against Moshe were designed using Stellaris single-molecule FISH probe designer software (www.singlemoleculefish.com) and synthesized by (Bioneer); for the negative control, LacZ probe sequences were obtained from Chu et al. [14]. All probe sequences used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table 4. Forty million cells were used for each reaction. Day 2 P19 cells were crosslinked with 1% Glutaraldehyde for 10 min followed by quenching in 1/10 volume of 1.25 M glycine. Sonication was performed using a Bioruptor (diagenode, Liege, Belgium) at 4°C for at least 45 min. Hybridization of biotinylated DNA probes was done at 37°C for overnight. qRT-PCR Primer for ChIRP analysis was listed in Supplementary Table 2. Enrichment of Nkx2.5 promoter DNA was presented by relative enrichment normalized by LacZ control. The lncRNA binding to the Nkx2.5 promoter regions was analysed at the putative binding loci (sites 3 and 5) more than twice and the lncRNA binding on site 3 was additionally confirmed, whereas the other sites with rare binding scores (site 1, site 2, site 4, site 6) were tested only in technical replicates.

DNA binding prediction for Moshe

The sequences of Moshe (1010001N08Rik-203) and Nkx2.5 promoter/enhancer region (Chr.17:26,833,664–26,851,565, Mus_musculus GRCm38.94) were obtained from the Ensembl database (asia.ensembl.org/index.html). The possible DNA binding motifs and sites of Moshe were predicted by the Long target computational program [15] with mean stability >1.0, identity >0.6, minimal TFO length >20. Only TFO-1 (Best TFO) of LncRNA was selected to predict the binding sites of DNA.

Transcription factor binding sites analysis for Nkx2.5

PROMO ver 3.0 (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgibin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB = TF_8.3) with 1% maximum matrix dissimilarity rate [16] and CiiiDER (http://ciiider.com/) with 0.15 deficits [17] were employed to investigate transcription factor-binding sites on the region of Nkx2.5 promoter/enhancer (Chr.17:26,833,664 to 26,851,565, Mus_musculus.GRCm38.94).

Prediction of Moshe and protein interactions

LncRNA-protein interaction prediction was performed using the lncPro computational method by following the manual (http://bioinfo.bjmu.edu.cn/lncpro/) [18]. Amino acid sequences for the putative candidate proteins were obtained from NCBI.

Animal tissues

All protocols involving animals have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (#SNU-170623-6-3). To obtained E8.5, E9.5 and E12.5 mouse embryos, pregnant ICR mice were purchased from the Orient bio a day before the experiment (Gyeonggi-do, Korea). The animals were sacrificed by CO2 chamber. Pig tissues were obtained from Majang-dong Livestock Association Market (Seoul, Korea). For the RNA isolation, chunks of tissues were preserved in RNAlater (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and homogenized in liquid nitrogen before being used.

Phylogenetic analysis and conserved domain research

The sequences of Moshe (1010001N08Rik-203), and GATA6 antisense transcripts in human (GATA6-AS1-201, GATA6-AS1-201, GATA6-AS1-202, GATA6-AS1-203, GATA6-AS1-204, GATA6-AS1-205, GATA6-AS1-206, GATA6-AS1-207, GATA6-AS1-208, GATA6-AS1-209) and pig (ENSSSCT00000038071, ENSSSCT00000039186) were taken from the Ensemble database. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model in MEGA7 software [19]. We utilized the Neighbour-Joining method on a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach. To further analyse conserved structure, the alignment results were depicted if the query coverage was >30% and the identical matches were >70% but removed if the aligned regions were not in the same order of exons for the same regions in the compared transcript pairs.

Statistics

Gene expression was measured and graphed using the delta delta CT of qRT-PCR. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was evaluated through the student's T-test and one-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism 8. Asterisk indicates * p-value <0.05, ** p-value <0.01, *** p-value <0.001, **** p-value <0.0001.

Results

1010001N08Rik, Gata6 antisense non-coding transcript identified as a candidate heart development-associated lncRNA

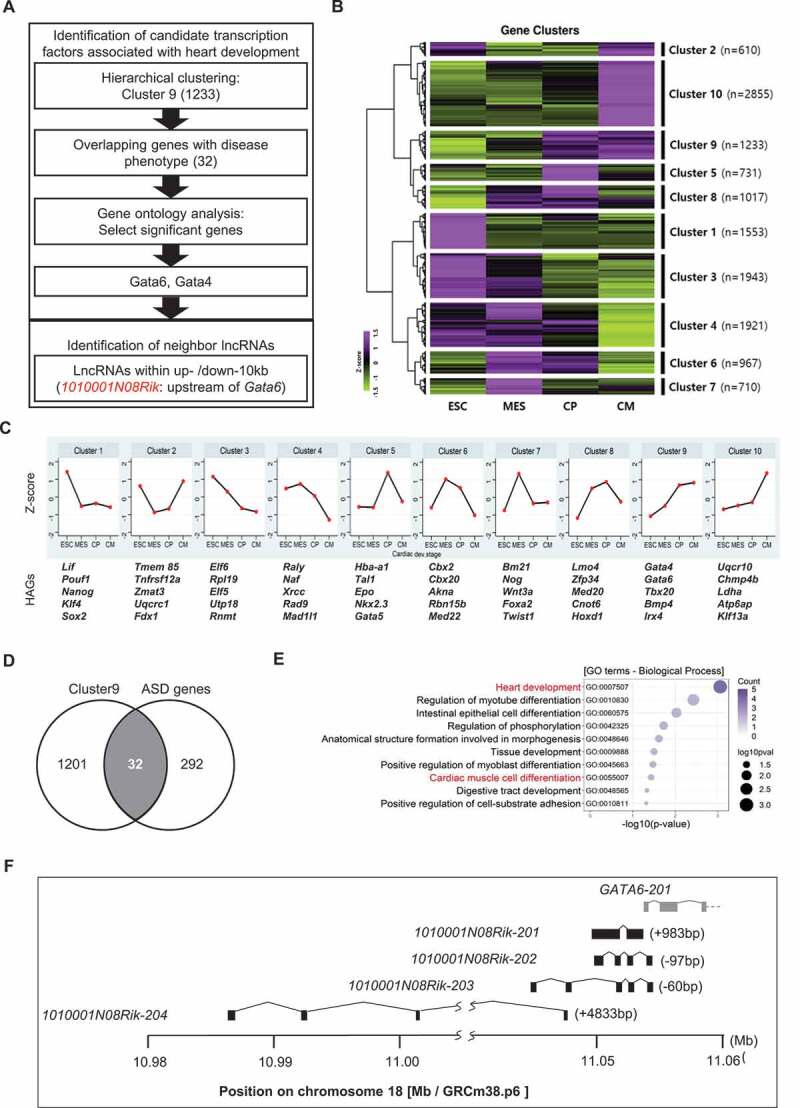

To investigate the lncRNA associated with cardiac differentiation, of which the abnormal expression could cause atrial septal defects (ASD), we first focused on the lncRNAs closely located in the genes associated with cardiomyocyte differentiation and ASD, which may thus act as cis-acting modulators. We analysed the public transcriptome data of cardiomyocyte differentiation performed by JA Wamstad et al. [9] and hierarchically clustered genes depending on expression profiles during cardiac development (Fig. 1A). Since the gene ontology (GO) analysis using the list of genes in each cluster revealed that cluster 9 indicates heart development (GO: 0007507; p-value = 4.12 E-09) and outflow tract morphogenesis (GO: 0003151; p-value = 4.66 E-04) which contains cardiac transcription factors, such as Gata4, Gata6 and Tbx20, we focused on cluster 9 consisting of 1,233 genes of which expression was drastically increased in the cardiac progenitor stage and maintained in the cardiac mesoderm stage (Figs. 1B and 1 C). These genes were then compared with a list of 136 upregulated and 186 downregulated genes in ASD patients [8] and was depicted in a Venn diagram (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, GO analysis using 32 overlapped genes, 24 up- and 8 down-regulated in ASD patients, indicated that most genes were enriched in diverse developmental processes including heart development (GO:0007507; p-value = 8.71E-04) and cardiac muscle cell differentiation (GO:0055007; p-value <0.01) (Fig. 1E). Two genes, Gata6 and Gata4, were finally nominated as key genes associated with heart development and disease. We then found neighbouring lncRNAs within 10kb upstream and downstream of the candidate genes. However, no lncRNAs were found near the Gata4 gene (NM_008092). We then identified 1010001N08Rik, Gata6 antisense transcripts, located on mouse chromosome 18: 10,987,944 to 11,052,567 (EMSMUSG00000097222), head to head, with an antisense orientation to Gata6 gene (NM_010258). Four different isoforms were predicted in the 1010001N08Rik region with various numbers of exons and sizes. The longest isoform, 1010001N08Rik-201 (ENSMUST00000180789) consisting of two exons with a size of 1,965 bp without an open reading frame (ORF) is located 983 bp upstream from the 5ʹend of Gata6. 1010001N08Rik-202 (ENSMUST00000181316) consisting of a 728 bp transcript with four exons is located in a 97 bp overlap with the 5ʹend of Gata6. 1010001N08Rik-203 (ENSMUST00000231895) has a 571 bp length with five exons and is also situated in a 60 bp overlap with the 5ʹend of Gata6. The 1010001N08Rik-204 consisting of 854 bp with four exons is located the furthest from the Gata6 start site by 4,833 bp (Figs. 1F and Fig 2B).

Figure 1.

Identification of 1010001N08Rik as a candidate of heart development-associated LncRNA. (A) Screening strategy for the identification of 1010001N08Rik. (B) Hierarchical clustering for gene expression in 4 cardiomyocyte differentiation stages. ESC: embryonic stem cells, MES: mesoderm cells, CP: cardiac progenitor cells, CM: cardiomyocytes. (C) Gene expression profiles in 10 different clusters. (D) Venn diagram using the genes in cluster 9 with ASD associated genes. (E) GO analysis in 32 common genes. Heart-related terms are highlighted in red. Number of counts in colour scale, circle size indicates p-value from Fisher’s exact test. (F) Four RNA structures of 1010001N08Rik isoforms near the Gata6 gene

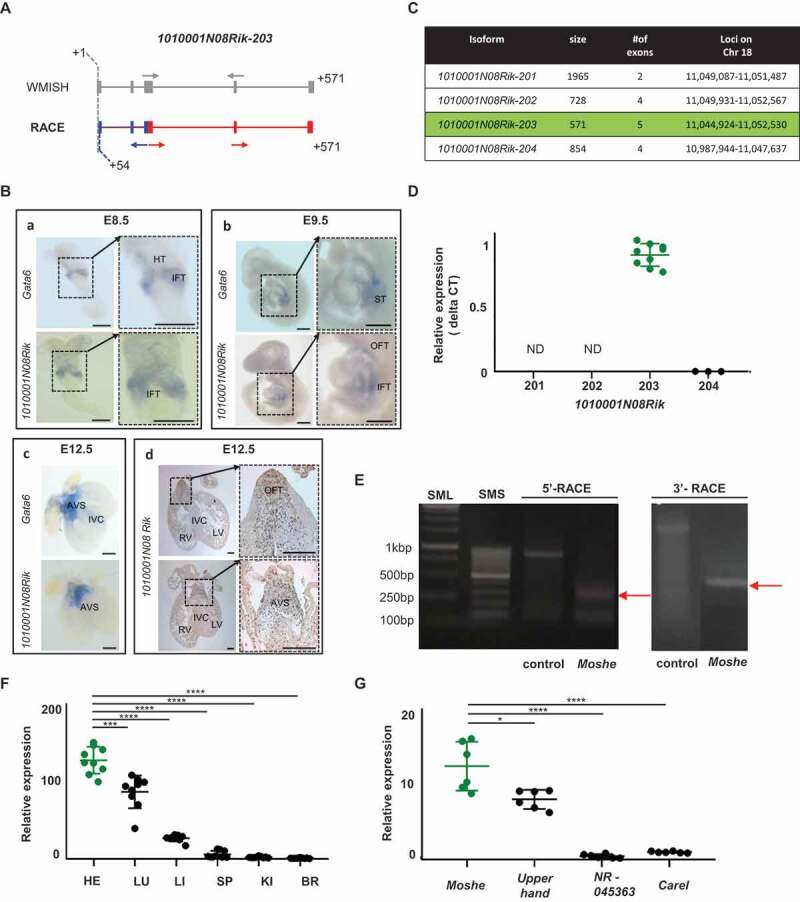

Figure 2.

Temporal and spatial expression of 1010001N08Rik-203 in heart development. (A) Overall scheme of Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) probes and primer for RACE PCR to detect Moshe. Transcript structures were captured from UCSC genome browser, and start and end locations are indicated in grey. Gray arrows: probe location of whole in situ hybridization. Blue and red structure indicates transcript expressed. Blue arrows: primer for 5ʹ-RACE; red arrows: primers for 3ʹ-RACE. The race PCR product starts from 54bp compare with 1010001N08Rik-203. (B) WMISH of E8.5 (n = 5), E9.5 (n = 11) embryos and E12.5 (n = 5) heart for both 1010001N08Rik and Gata6. IFT: inflow tract, HT: heart tube, ST: septum transversum, AVS: atrioventricular septum, RV: right ventricle, LV: left ventricle, IVC: interventricular septum, OFT: outflow tract. Scale bars: 250 μm (A, D), and 500 μm (B, C). (C) Four major isoforms of 1010001N08Rik are listed with general information, size, # of exons and loci. 1010001N08Rik-203 is highlighted in green. (D) 1010001N08Rik expression relative to the Hmbs (hydroxylmethylbilane synthase) gene. Green indicates 1010001N08Rik-203, a major isoform expressed in embryonic heart. Isoform-201 and −202 were not detected in E12.5 heart (ND). Significant difference between 1010001N08Rik-203 and 1010001N08Rik-204 was tested by student t-test. (E) The race PCR product starts from 54bp compared with 1010001N08Rik-203 hypothetical prediction. Expected size in 5′-and 3′-RACE is depicted with the result of DNA agarose gel electrophoresis. 5ʹRACE control: GeneRacerTM 5ʹNested Primer + Control primer + human β-actin template (858bp) 3ʹRACE control: Gene RacerTM3ʹPrimer +control primer+ human β-actin template (~ 1800bp) (F) Relative expression of lncRNA Moshe, in the major adult tissues: HE (heart), LU (lung), LI (liver), SP (spleen), KI (kidney) and BR (brain). Heart in green. (n = 3), Data was analysed by ANOVA test. (G) Upperhand (NR_154048.1), and NR 045363, Carel (NONMMUT070401) were selected as heart-specific lncRNA. (n = 3), Data was analysed by ANOVA test. Moshe in green. Error bars indicate SD, p-value < 0.005

The expression of lncRNA Moshe was spatially regulated in mouse heart development

To detect expression and localization of 1010001N08Rik lncRNA during development, we performed whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) in mouse embryos and adult heart sections. The overall scheme with probe designed to cover all three isoforms 1010001N08Rik-201, −202 and −203 and primers used for the detection of 1010001N08Rik-203 were depicted in Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1. 1010001N08Rik-204 was excluded due to its absence in the UCSC genome browser (ver. NCBI37/mm9, July 2007). LncRNA expressions were examined at development stages, E8.5, E9.5 and E12.5. As reported in previous studies, Gata6 is observed in the inflow tract or sinus venosus and the heart tube at E8.5 and E9.5 [20]. At E12.5, Gata6 was also detected in the atrioventricular septum and the outflow tract [21] (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 2). The Gata6 gene was also detected in the septum transversum region [22], which involves the hepatic endoderm in E9.5 and the interventricular septum at E12.5 [23]. Interestingly, LncRNA 1010001N08Rik was expressed in the similar regions where Gata6 was expressed, including in the atrioventricular septum (AVS) region during cardiac development [24], even though Gata6 was more broadly expressed in the heart tube, septum transversum and interventricular septum. This might be meaningful, since the AVS region where both lncRNA 1010001N08Rik and Gata6 expression was detected at E12.5 is directly associated with ASD when incorrectly formed and Gata6 has major roles in ASD.

To determine which isoforms of 1010001N08Rik have a role in cardiac development, we performed qRT-PCR and rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). Isoform-specific primers were designed based on Ensembl transcript structures (Supplementary Table 1). qRT-PCR of four different isoforms in the embryonic heart revealed that 1010001N08Rik-203 is a unique transcript expressed in cardiac development (Fig. 2C and Fig. 2D). The identification of 1010001N08Rik-203 was partially confirmed by RACE analysis. Unexpectedly, the start-sites of the transcripts were shorter than the predicted RNA structure from the Ensembl database, but exon structure was matched to1010001N08Rik-203. The transcript started from +54 bp and ended at 571 bp according to the 1010001N08Rik-203 structure (Figs. 2A, 2E and Supplementary Fig. 3). Hereinafter we named the lncRNA 1010001N08Rik-203 as Moshe (MOdulating Second HEart field progenitor) that is located on Chr18:11,044924 to 11,052,530 (-strand, GRCm38.p6). Spatial expression of Moshe was analysed in the representative mouse tissues including heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney and brain (Fig. 2F). Although, Moshe expression was detected in several adult mouse tissues, the expression level was significantly higher in the heart. Of note, when the expression of Moshe was compared to other lncRNAs previously known in cardiomyogenesis, Moshe was as highly expressed as other lncRNAs such as Upperhand (NR_154048.1) which is well known for heart development and disease (Fig. 2G).

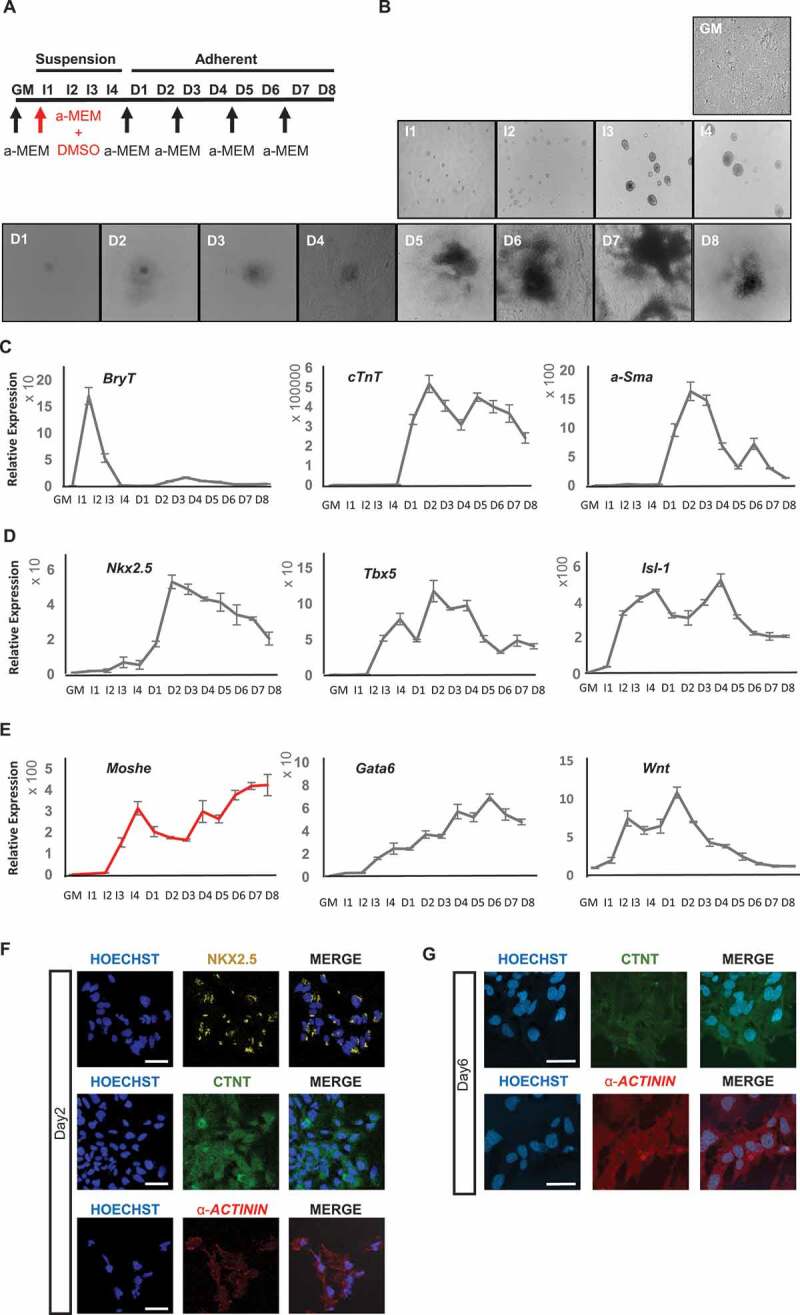

Moshe is highly expressed in cardiac mesoderm and cardiac progenitor stages during cardiac differentiation in vitro.

To examine the temporal expression pattern of Moshe during cardiomyocyte development, we differentiated P19, a multipotent cell line that can differentiate efficiently from mesodermal lineages, to cardiomyocytes [25]. The scheme of the cardiac differentiation procedure of the P19 cell line with 4 days embryonic body formation in the presence of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) was depicted in Fig. 3A [10]. Subsequently, cardiomyocytes were successfully matured around 6 days after being cultured without DMSO (Fig. 3B). Appropriate differentiation was analysed by qRT-PCR using the following three stage-specific marker genes, BrachryT (BryT) for the mesoderm stage, alpha-Smooth muscle actin (a-Sma) for cardiac progenitor cells and smooth muscle, and cardiac troponinT (cTnT) for cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3C). BryT that represents the mesoderm stage was highly expressed on Induction day-1(I-1). Cardiac progenitor cells, represented by a-Sma, exhibited from differentiation day (D)-1 and gradually decreased to D-5. As with a-Sma, cardiomyocyte maker cTnT was expressed from D-1, but was consistently maintained until D-8. In addition, the expression of three key transcription factors in FHF and SHF progenitor cells, Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Isl1 that mainly function from the cardiac mesoderm to the cardiac progenitor stages were tested (Fig. 3D). The expression of Tbx5 and Isl1 increased from I-2 and were highly expressed until D-5 in a dynamic pattern. Nkx2.5, which is important in the cardiac progenitor stage, was expressed from D-1 until the end of the cardiomyocyte differentiation (D-8), similar to cTnT expression. These results are consistent with transcriptome data obtained from mESC to cardiomyocyte differentiation [26]. Based on the stage marker expression profile, the cardiomyocyte differentiation stages were defined thusly: the mesoderm stage was assigned from I-1 to I-2, cardiac mesoderm stage from I-3 to I-4, cardiac progenitor stage from D-1 to D-5, and mature cardiomyocyte stage from D-6 to D-8. Altogether, Fig. 3 shows that cardiomyocyte differentiation using P19 cell line was done properly.

During cardiomyocyte differentiation, Moshe expression fluctuated from I-2 through D-8 (Fig. 3E). The expression was detected from I-2 and sharply increased until I-4 (cardiac mesoderm stage) but decreased with differentiation until D-2. However, after D-2, Moshe expression continuously increased until D-8, the end of differentiation stage. In the meantime, Gata6 expression steadily increased from the induction start until D-6 when cardiomyocytes are fully matured. According to WMISH data and in vitro cardiomyocyte differentiation, Moshe appears to be regulated similarly to Gata6 but different in at least some stages and regions. Wnt2, which has been known to play an important role in early stages of cardiomyocyte differentiation and also in the posterior region of heart by regulating Gata6 [24], was also tested and compared to see if any correlation was found with Moshe and Gata6 expression. The expression pattern of Wnt2 was highly detected at I-2 and peaked at D-1 but then gradually decreased until the end. This indicates that Wnt2 may not closely related with Moshe and Gata6 expression.

Figure 3.

Moshe and related gene expression during cardiac differentiation. (A) Schematic diagram for the cardiomyogenic differentiation of P19 EC cell. GM: growth medium, I: induction with DMSO cultured in bacterial petri dishes, D: differentiation in cell culture dishes. Arrows indicate changing culture medium (α -MEM). (B) Representative images of cardiomyogenesis from P19 cells. (C) Relative gene expression of BryT, α-Sma and cTnT as a marker for cardiac differentiation. (D) Relative gene expression of three major transcription factors, Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Isl1. (E) Relative expression of Moshe during cardiac differentiation (red) and putative associated genes, Gata6 and Wnt2.

Error bars indicate SD. (F) Representative images for immunofluorescence staining at differentiation day2 (NKX2.5, α-ACTININ, cTNT). Size bar = 50 μm.

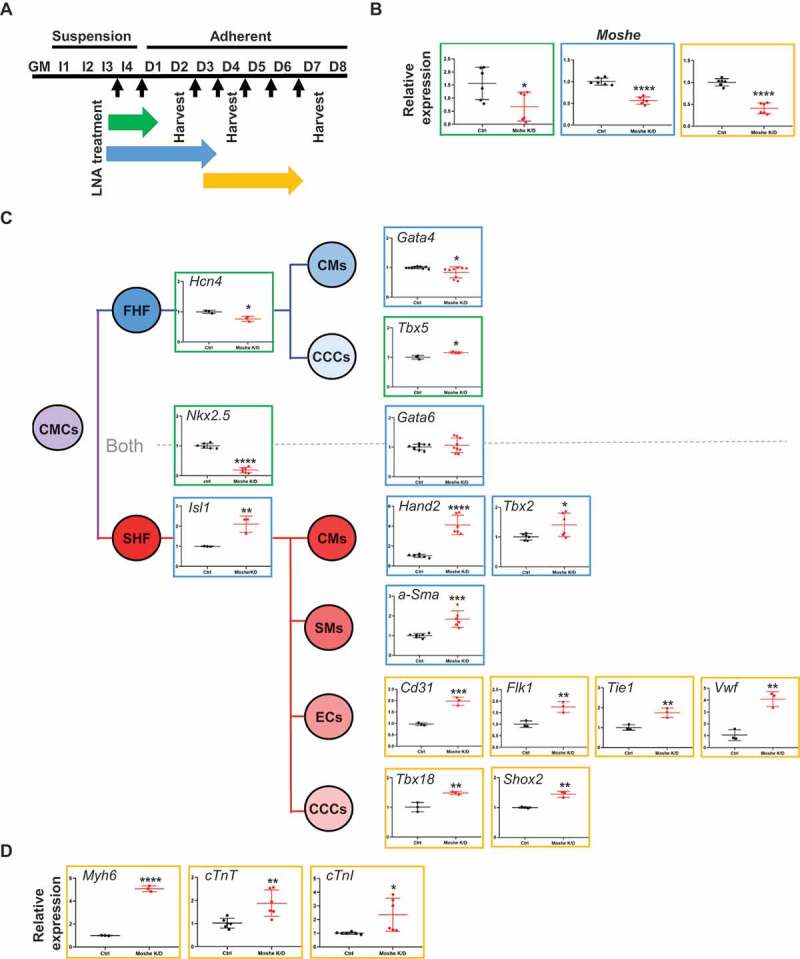

Moshe negatively regulates SHF genes during cardiac differentiation in vitro

We next investigated the function of Moshe by knockdown using antisense LNA (Locked Nucleic Acids) oligos at the intron 3 region (Supplementary Table 3). Since, Moshe is expressed at the early stages of embryonic heart differentiation, knockdown was performed throughout three different stages, from the cardiac mesoderm to early cardiac progenitor stage by treating LNA from I-4 to D-1, late cardiac progenitor stage by treating LNA from I-4 to D-3, and late progenitor stage to mature cardiomyocyte stages by treating LNA from D-3 to D-6 (Fig. 4A). Since the P19 cells were grown spherically, they were treated and harvested after consistent treatment. Moshe silencing successfully reduced its transcription level down to ~20% (Fig. 4B). First, Moshe knockdown led to a dramatic decrease in cardiac progenitor inducer Nkx2.5 gene expression, whereas the adjacent cardiac transcription factor, Gata6, had no significant changes (Fig. 4C). One interesting finding was that even though Moshe knockdown led to a decrease in cardiac progenitor inducer Nkx2.5, silencing Moshe significantly affected SHF lineage cells in the early and late cardiac progenitor stages. Silencing Moshe increased the gene expression of SHF genes such as Isl-1, Hand2 and Tbx2, whereas the expression levels of Hcn4, Tbx5 and Gata4 known as the FHF genes were not notably changed. Gata6 and Gata4, the genes expressed in both heart fields, were not significantly changed. This is consistent with previous studies that Isl1 and Nkx2.5 repress each other and regulate SHF proliferation, differentiation and patterning (Fig. 4C) [4,27]. Silencing Moshe increased certain SHF lineage cell makers, such as a-Sma (smooth muscle cell marker), Cd31, Flk1 Tie1 and vWF (endocardial cell markers), Tbx18 and Shox2 (sinoatrial node markers). Consequently, well-known mature cardiomyocyte marker genes, Myh6, cTnT and cTnI, were also increased under the Moshe knock-down condition (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of Moshe and altered heart-related gene expression. (A) Schematic diagram of Moshe knock-down in PC19 cells by the treatment of Moshe antisense LNA. Black arrow for LNA treatments. Three different stages are indicated: early cardiac progenitor stage (green), late cardiac progenitor (blue), and mature cardiomyocyte progenitor stage (yellow). (B) Depleted Moshe expression was measured by qRT-PCR. Colours indicate corresponding stages in (A). (C) Representative cardiac differentiation marker gene expressions under Moshe depletion is depicted in corresponding cell and SHF lineage is highlighted with the red line. CMCs: cardiac mesodermal cells, FHF: first heart field, SHF: second heart field, CMs: cardiomyocytes, CCC: cardiac conduction cells, SM: smooth muscle cells, and EC: endocardial cells. (D) Three marker gene expressions for mature cardiomyocytes. Data was analysed by student’s t-test. Error bars indicate SD. Asterisk indicates * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value < 0.0001

Altogether, these results may suggest that Moshe plays a role in fine-tuning processes by repressing SHF genes via activating the Nkx2.5 gene from properly differentiating into SHF lineage cells.

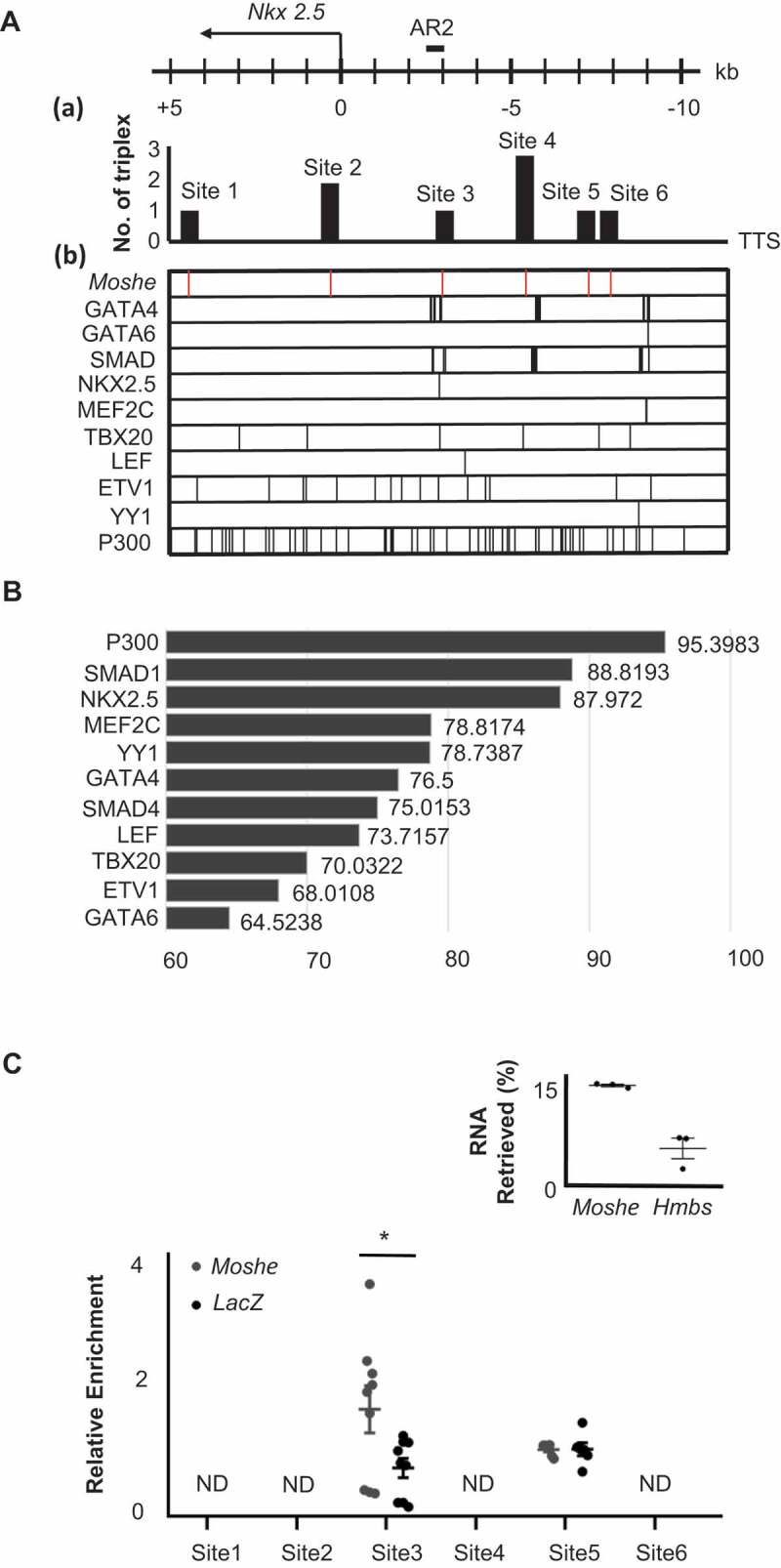

Moshe regulates Nkx2.5 gene expression via direct binding to its promoter region

Since Nkx2.5 was dramatically decreased in the Moshe knockdown condition in the present study, and it is known that the expression of Nkx2.5 with Isl1 in SHF cells represses each other to make the appropriate subtype identity, which results in proper heart development [3,27,28], we first analysed whether Moshe regulates Nkx2.5 via direct interaction. We employed the LongTarget program to identify possible Moshe binding sites on the Nkx2.5 promoter and enhancer regions [15]. The predicted binding motifs on Moshe and the target motif on the promoter and enhancer regions of Nkx2.5 were identified by triplex-forming oligos (TFO) and triplex target sites (TTS). A total of six TTSs were found with TFO-1 (the best TFO) from a −10 kb upstream to a +5 kb downstream region of the Nkx2.5 transcription start site (TSS) (Chr.17: 26,833,664 to 26,851,565, Mus musculus. GRCm38.94). The six TSSs including chromosomal position, relative loci to Nkx2.5, and numbers of triplex are listed in Table 1. The fourth TTS, site 4, showed the highest score, followed by site 2 (Fig. 5A (a)). To investigate the role of Moshe on Nkx2.5 expression, we also surveyed transcription factor (TF) binding motifs on the Nkx2.5 promoter region using PROMO and CIIIDER. Previous studies have reported that several TFs can bind to the promoter and enhancer regions of Nkx2.5 [27,29,30] (Fig. 5A (b)). Remarkably, nine TFs, P300, SMAD1, NKX2.5, MEF2C, YY1, GATA4, SMAD4, LEF and TBX20, were predicted to bind with Moshe with a high score (>70) (Fig. 5B). We confirmed the in silico prediction that Moshe binds to Nkx2.5 promoter regions by chromatin isolation using RNA purification (ChIRP) PCR analysis (Fig. 5C). Approximately 14% of Moshe transcripts were retrieved from the input solution when ~5% Hmbs, which is the unspecific control, was retrieved. Unexpectedly, no Nkx2.5 amplicon was detected from the TTS site 4 region where the best triplex was found. Two out of the six TTSs, site 3 and site 5, were amplified and only site 3 showed the enrichment of Nkx2.5 in Moshe when compared to a LacZ control. This result successfully showed that Moshe physically interacts with the Nkx2.5 promoter region via TTS site 3, −3045 bp to −3102 bp upstream of Nkx2.5 (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, most of the proteins that bind to TTS site 3, in particular five TFs, P300, SMAD1, NKX2.5, GATA4 and SMAD4, were demonstrated to be Nkx2.5 activating proteins (Fig. 5A) [29–31]. This is consistent with the previous reports that SMAD4 and GATA4 bind to AR2 enhancers of Nkx2.5 (in the region −3080 to −2673 upstream of the TSS) and that show histone acetylation occurs in this region by using a ChIP assay with anti-acetylated histone H4 [27,29,30].

Table 1.

Location of predicted TTS site by long target

| TSS site | Location | ~bp apart from TSS site of Nkx2.5 | # of triplex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26,837,097 ~ 26,837,143 | +4468 ~ +4422 | 1 |

| 2 | 26,841,233 ~ 26,841,300 | +332 ~ +265 | 2 |

| 3 | 26,844,610 ~ 26,844,667 | −3045 ~ – 3102 | 1 |

| 4 | 26,846,935 ~ 26,846,955 | −5370 ~ – 5390 | 3 |

| 1 | 26,848,910 ~ 26,848,930 | −7345 ~ −7365 | 1 |

| 6 | 26,849,497 ~ 26,849,544 | −7932 ~ −7979 | 1 |

*Input sequence for LongTarget analysis starts from Chromosome: GRCm38:17:26,833,664 to 26,851,565

*Long target analysis predicted 6 triplex target sites (TTS) from the best triplex-forming oligonucleotides, TFO-1.

*Lane 3 indicates how much TTS sites were apart from transcription start site (TSS) of Nkx2.5.

Nkx2.5 starts from chromosome 17: 26,838,664 to 26,841,565

* # of triplexs: number of triplexes generated from TFO-1

Figure 5.

Moshe regulates Nkx2.5 via direct binding to AR2 enhancer region. (A) Six Moshe TTSs (a) with ten TF binding sites (B) on the Nkx2.5 promoter/enhancer region are depicted. AR2 enhancer was indicated at around −3kb upstream from TSS. (B) The binding affinity of 11 candidate proteins to Moshe. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of ChIRP RNA shows % retrieval of Moshe compared with Hmbs unspecific control. qRT-PCR of ChIRP DNA shows amplification of Nkx2.5 promoter/enhancer regions at the TTS site 3 and site 5. Asterisks were added with student’s t-test results. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. * indicates p-value < 0.05, ND: not detected

Altogether, it is expected that the regulation of Nkx2.5 expression by Moshe occurs due to the direct binding of Moshe to nkx2.5 promoter region (−3015 bp to −3102 bp) which can recruit several important transcription factors on the site both temporal and spatial.

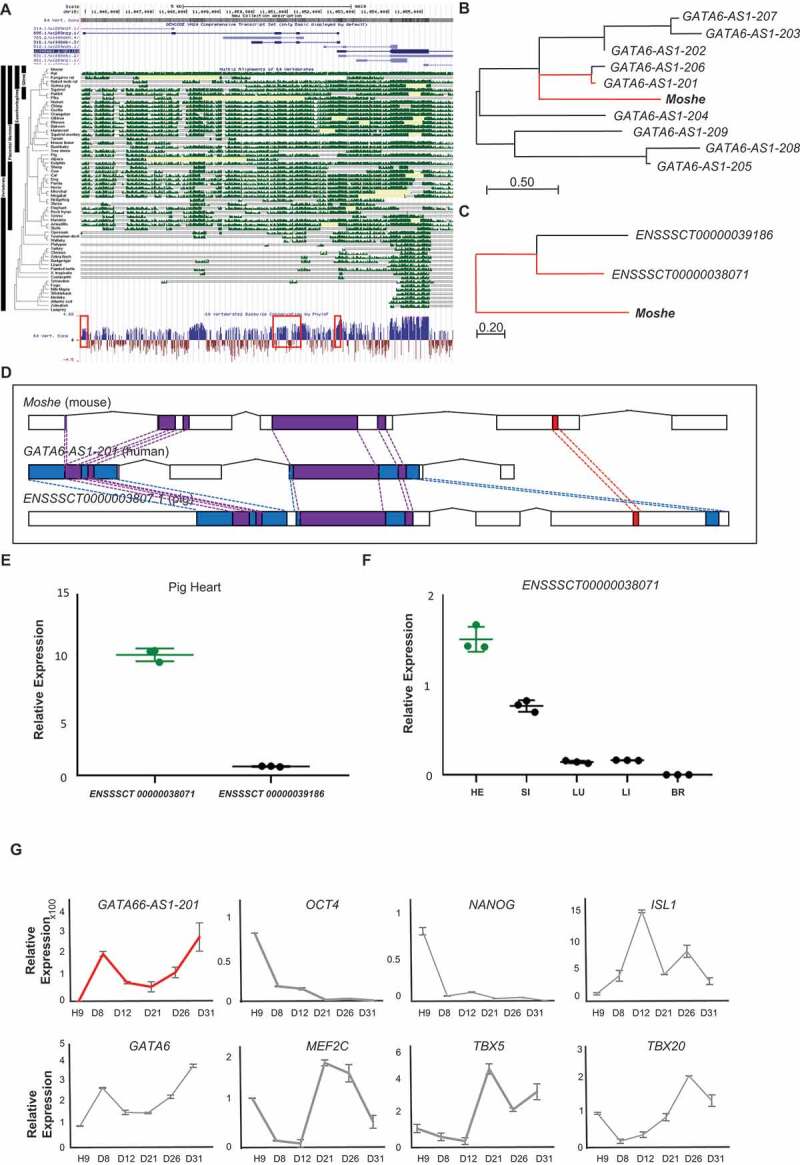

Moshe is a lncRNA highly conserved in sequence and function across species

To gain insights into functional relevance across species, we first assessed the overall conservation of Moshe in diverse vertebrate genomes obtained from USCS genome browser. It is known that numerous lncRNAs are not conserved in sequence across various species and tissues. Notably, the flanking genomic region of the Moshe sequence on mouse chromosome 18 (chr18: 11,044,924 to 11,052,530), 60 bp upstream from the transcription start site of Gata6, is highly conserved across placental mammalian genomes in the Multiz alignments of the UCSC genome browser (Fig. 6A). Nucleotide sequence conservation in the 60 vertebrates by PhyloP also presented a well-conserved exon structure, especially in the 170–360 bp region (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 6.

Cross-species conservation of Moshe in sequence and expression profiles. (A) Regional conservation of Moshe in 60 vertebrate genomes including human and mouse. UCSC genome browser presents the mouse genomic region of 1010001N08Rik-203 (chr18:11,044,924 to 11,052,530) with exon structure in blue, Multiz Alignments of 60 vertebrates in green, and PhyloP in blue and red. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of Moshe with 9 orthologous transcripts in human: GATA6-AS1-201: ENST00000579431, GATA6-AS1-202:ENST00000583490, GATA6-AS1-203:ENST00000584201 GATA6-AS1-204:ENST00000584373, GATA6-AS1-205:ENST00000684976, GATA6-AS1-206: ENST00000649008, GATA6-AS1-207:ENST00000649729, GATA6-AS1-208:ENST00000650323, GATA6-AS1-209: ENST00000650586. (C) Multiple sequence alignment of Moshe with 2 orthologous transcripts in pig: ENSSSCT00000039188 and ENSSSCT00000038071. (D) Conserved regions in all three species in purple, conserved regions between mouse and human in blue, and conserved region between mouse and pig in red. (E) Only ENSSSCT00000038071 transcript was detected from adult heart in pig. p-value was calculated by student’s t-test. (F) Tissue-wise pig orthologue expression of Moshe was tested in HE: heart, SI: small intestine, LU: lung, LI: liver and BR: brain by one-way ANOVA. (G) The stage specific Moshe orthologue (GATA6-AS1-201) expression was analysed with differentiation marker genes in the cardiac differentiation of human H9 cells. GATA6-AS1-201 in red, OCT4, NANOG, GATA6, ISL1, MEF2C, TBX5 and TBX20 represent stage specific markers. Error bars indicate SD, p-value < 0.001

We then compared transcript sequences from human and pig to determine Moshe orthologues. The domestic pig (Sus scrofa) is a good model animal for the study of various heart diseases due to their genetic and structural similarities with human hearts [32]. There are nine and two transcripts predicted in the conserved region of Moshe and the antisense direction of GATA6 in the human and pig genome, respectively (GATA6-AS1-201, GATA6-AS1-202, GATA6-AS1-203, GATA6-AS1-204, GATA6-AS1-205, GATA6-AS1-206, GATA6-AS1-207, GATA6-AS1-208 and GATA6-AS1-209 in human and ENSSSCT00000038071 and ENSSSCT00000039186 in pig). A Phylogenetic analysis for detailed conservation was performed by MEGA using the Neighbour-Joining method on a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach [19] and showed that the transcripts of GATA6-AS1-201 in human and ENSSSCT00000038071 in pig were the most similar to Moshe (Fig. 6B-C). According to the BLASTn result, alignments of GATA6-AS1-201 share 38% query cover and 81.68% identity with Moshe. ENSSSCT00000038071 shares 49% query cover and 74.21% identity with Moshe. Moreover, ENSSSCT00000038071 shares 89% query cover and 84.62% identity with GATA6-AS1-201 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, our result indicated that Moshe is regionally and sequentially conserved in mammals, from pigs to humans (Fig. 6D).

To further characterize the role of conserved lncRNAs, we evaluated their tissue-wise expression profiles. In pig, ENSSSCT00000038071, which is the most tightly conserved transcript with Moshe, was confirmed as a putative orthologue of Moshe by qRT-PCR. In contrast to the other transcript ENSSSCT00000039186, only the ENSSSCT00000038071 transcript was detected from pig heart (Fig. 6E). Also, tissue-wise ENSSSCT00000038071 expression revealed that heart expresses ENSSSCT00000038071 transcript the highest amongst other tissues, similar to Moshe in mouse (Fig. 6F). In human, the heart-specific expression of GATA6-AS-201 was previously reported in the transcriptome analysis of 15 human tissues [33]. Tissue-wise investigation of GATA6-AS-201 expression showed unique expression in human heart tissue. We indeed investigated the expression profile of GATA6-AS1-201 during human embryonic stem cell differentiation (Fig. 6G). Human embryonic stem cell differentiation in vitro was evaluated by the expression profiles of stem cell pluripotency markers (OCT4 and NANOG) and cardiac differentiation markers (MEF2C, TBX5, TBX20, ISL1,NKX2.5 and GATA6) (Fig. 6G, Supplementary Fig. 5). During human embryonic stem cell differentiation, GATA6-AS-201 showed increased expression in two separate stages, with high expression at cardiac day 8 (D8), decreased until cardiac day 21 (D21) and then gradually increased until cardiac day 31 (D31), which is a very similar to in vitro Moshe cardiac differentiation using P19 cell line (Fig. 3E). Altogether, the heart-specific molecular function of Moshe seems to be well conserved in heart development from mouse to human. Further studies of knock-out mouse study might reveal the function of Moshe in vivo.

Discussion

Antisense lncRNA as a cis-regulatory modulator can regulate neighbouring gene expression. For instance, LncRNA-uc.167 located in the opposite strand of Mef2c is highly expressed in patients with ventricular septal defect (VSD) and inhibits Mef2c and cardiomyocyte proliferation [34]. From the same point of view, we first searched for key genes (Gata6 and Gata4) associated with heart development and ASD by re-analysing public data sets to identify antisense regulator lncRNA. A lncRNA 1010001N08Rik-203, which we named Moshe, is located in Chromosome 18: 11,044,924 to 11,052,530 in the antisense direction of Gata6 (Chromosome 18: 11,052,470 to 11,085,635) overlapping by 60 nucleotides. There are four different isoforms of 1010001N08Rik predicted including Moshe, but only Moshe was heart-specifically regulated (Fig. 2C). We performed WMISH with 1010001N08Rik-201, but no cardiac specific expression was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2). Also, isoform 1010001N08Rik-202, also called LncGata6, is known to be highly expressed in the small intestine, epithelial lineages [35]. Moreover, even though the regional expression pattern of Moshe is similar to Gata6 expression during heart development, there are clear discrepancies between the temporal and spatial expression patterns of Moshe and Gata6. For instance, both Moshe and Gata6 expressions were increased throughout cardiac differentiation, but Moshe peaked at the cardiac mesoderm stages (I-4) gradually decreased until D-4, then gradually increased after D-4, whereas Gata6 gradually increased throughout (Fig. 3B). Moreover, Gata6 expression was wider to septum transversum and inter-ventricular septum. Altogether, these results may indicate that Moshe and Gata6 are not regulated in a closely related manner but rather independently to some degree.

The putative function of Moshe in heart development was examined through its knockdown during heart differentiation using the P19 cell line. Knockdown of Moshe didn’t affect Gata6 expression (Fig. 4C). This result confirmed that Moshe is not just a cis-acting regulator of Gata6 but a Gata6-independent trans-modulator of heart-related gene expression. The association between Gata6 and Gata6 antisense transcript isoforms has been reported in some tissues and cells as well as conditions. Isoform 1010001N08Rik-202, also called LncGata6 acts trans to promotes Ehf transcript expression to repress endothelial mesenchymal transition [35]. In human, GATA6-AS1-202, one of the GATA6 antisense transcripts, has been reported in controlling endothelial cell expression and angiogenesis in the hypoxic state and also trans regulates POSTN or PTGS [36]. Thus, the Gata6-AS-202 antisense lncRNA is likely to act on genes as a trans regulator.

We investigated genes that are considered as important during the development of FHF and SHF by literature survey. The FHF progenitor differentiates into left cardiomyocytes, atrial cardiomyocytes, cardiac conduction cells and atrioventricular canal. On the other hand, the SHF progenitor differentiates into right ventricular cardiomyocytes, atrial cardiomyocytes, cardiac conduction cells, outflow tract cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells [26]. It is well known that Hcn4 is a specific marker for the FHF progenitor and conduction cells [37], whereas Shox2 expressed in SHF progenitors is important for cardiac pacemaker differentiation [38]. Some genes known to be expressed in both FHF and SHF, such as Tbx2 and Tbx5, were classified based on their importance in each field. For instance, Tbx2 is expressed in the posterior part of the cardiac tube at E8.5 and its expression only extends to include the OFT (outflow tract) region and atrioventricular canal at E9.5 [39–41]. Even though the atrioventricular canal is derived from both FHF and SHF, misexpression of Tbx2 in the early stages of embryonic mouse heart development represses proliferation and impairs SHF progenitor cell deployment into the OFT [42]. We thus classified Tbx2 as an SHF gene. Also, Tbx5 is generally used as an FHF marker gene. This is because it is first detected at E7.5 in the cardiac crescent and the FHF and only later is it detected at the pSFH (posterior second heart field) [2]. Furthermore, Tbx5 overexpression in murine models prefers an FHF lineage by down regulating BMP4 and Hand2 [43]. In this study, we treated LNA from their Induction3 at the cardiac mesoderm stages until day 2, the early cardiac progenitor stage. Therefore, we classified Tbx5 into FHF genes.

We then analysed diverse genes expressions associated with cardiac differentiation and influenced by the knockdown of Moshe (Fig. 4C). Nkx2.5 expression was drastically repressed under Moshe depletion in conjunction with increased Isl1, which may lead to significant up-regulation of SHF genes expression. All genes tested for the cardiomyocytes (CMs), endothelial cells (ECs), smooth muscles (SMs) and cardiac conduction cells (CCCs), especially sinoatrial nodal cells originated from SHF, were significantly up-regulated under Moshe depletion (cTnT, cTnI and MYH6 for CM; Cd31, Flk1, Tie1 and vWF for ECs; a-Sma for SMs; Shox2 for CCCs). However, the FHF genes, Tbx5, were unchanged and Hcn4 was slightly decreased. These results might indicate that Moshe activates Nkx2.5 and suppresses Isl1 genes that are SHF regulators either directly or indirectly, thereby suppressing the SHF gene regulatory network at the proper level.

It has been known that the maintenance of specific gene expression at the appropriate level is critical in heart development. The lncRNA function involved in maintaining the dosage level of genes has been proposed for heart development. For example, Handsdown, also regulates cardiac gene programs by decreasing Hand2, Hand1, Nkx2.5, Myl7 and cTnT expression levels to tightly control the gene dosage level for proper development [44]. Similarly, our results demonstrate that the upregulation of Nkx2.5 by lncRNA Moshe lowers the expression of SHF-related genes and controls appropriate gene levels in order for heart development to occur properly. The importance of Nkx2.5 and Isl1 genes in SHF has also been demonstrated in regard to various aspects. Nkx2.5 null mutations upregulate progenitor signature of SHF genes including Isl1 and show persistent abnormal expression of SHF genes in differentiating cardiomyocytes [28]. It was later shown that Nkx2.5 is a direct repressive mediator of Isl1 by binding Isl1 enhancer during SHF progenitor differentiation in vivo. Direct repression of Isl1 by Nkx2.5 binding to Isl1 enhancer suppresses Isl1 downstream targets and regulates myocardial differentiation and myocyte subtype identity [3,4]. Our data also indeed showed that Moshe knockdown resulted in the decrease of Nkx2.5 and upregulation of Isl1 and subsequent increases of SHF-related Isl1 downstream targets (Fig. 4C). Therefore, it is likely that Moshe trans activates Nkx2.5 in SHF development. Nkx2.5 is also known to suppress the proliferation of atrial myocytes and the cardiac conduction system. The atria emerges from the venous pole of the heart tube where Moshe is expressed at E8.5 and E9.5 (Fig. 2B), which is a subset of SHF and malfunctions in this area cause heart diseases such as ASD and arrhythmia. Atrial specific Nkx2.5 knockdown shows extensive enlargement of the working cardiomyocytes and cardiac conduction system and leads to ASD, hyperplasic myocardium, AV conduction block and pulmonary hypertension [45]. In addition, several studies reported abnormal expression of Nkx2.5 in ASD patients [46]. It is also known that mesodermal Nkx2.5 is essential for early SHF development and plays important roles in establishing the outflow and inflow tracts at the anterior SHF (aSHF) and posterior SHF (pSHF) during cardiac development [47,48]. Therefore, our data may indicate that Moshe contributes to the proper SHF development through tight spatial and temporal control of Nkx2.5 dosage, so that this delicate regulation process of the gene regulatory network in SHF can be achieved.

Among the regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs, the regulation of target gene expression via regulating the binding of chromatin modifying enzymes, as well as recruiting transcription factors, have been well-documented [7]. This study also suggested that Moshe controls Nkx2.5 expression at the Nkx2.5 enhancer region via recruiting chromatin regulator P300 and GATA4/SMAD complexes (Fig. 5B). Indeed, our ChIRP data confirm that Moshe binds to the Nkx2.5 promoter region via TTS site 3 ~3 kb upstream from the TSS (Fig. 5), a region known to be an AR2 enhancer. The function of GATA4 and SMAD4 associated with Nkx2.5 in heart development has been reported in many studies. For instance, it is known that the binding of GATA4 and SMAD4 to this region promotes Nkx2.5 expression [29,30]. GATA4 and SMAD1/4 in Nkx2.5 cooperates via BMP2 signalling has also been reported [27]. BMP2-mediated signalling is known to be important for AV canal and valve formation [49]. Of note, BMP2 signalling coincides with Moshe expression. Moreover, the cooperation of HAT P300 with GATA4 has been reported in non-chamber myocardial regions including the AV canal, sinus venosus and outflow tract where Moshe is expressed [31]. Also, post-translational modification of GATA4 via physical interaction with chromatin remodelling enzymes, such as histone acetylation transferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC), is crucial for cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation [50]. In the present study, we showed that TFs such as GATA4, SMAD and P300 that are known to bind to the AR2 enhancer region with a high binding score (>75) are capable of interacting with Moshe (Fig. 5B). The expression of GATA4 protein, which is known to be a transcriptional activator and shares a binding site with Moshe on Nkx2.5 promoter region (Fig. 5), is decreased in cardiomyocyte maturation stage when Moshe increases but Nkx2.5 decrease [10]. This explains Moshe and Nkx2.5 expression during cardiomyocyte development does not show a clear correlation in each other (Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D), Moshe regulate Nkx2.5 expression in spatial and temporal. Therefore, we speculate that Moshe promotes Nkx2.5 expression via recruiting GATA4, SMAD and P300.

The high cross-species conservation of Moshe found in sequence among mouse, pig and human may strengthen our finding that Moshe has a crucial role in cardiovascular development. Many lncRNAs lack conservation in sequence and functionality among species. Nevertheless, cross-species conservation is widely used as an indicator of the functional significance of the lncRNA. In this study, Moshe and its orthologues are also positionally conserved in the antisense direction of Gata6. Moshe shared the highest query cover (38%) and identity (81.68%) with its human orthologue (GATA6-AS1-201) and 49% query cover and 74.21% identity with its orthologue (ENSSSCT00000038071) in domestic pig (Sus scrofa). Even though ENSSSCT00000038071 has a relatively low identity against 1010001N08Rik-203 compared with the human orthologue, it has a larger query cover than the human isoform (49% vs 38%). In a tissue-wide RNA expression profile, the heart-specific expression of human orthologues (GATA6-AS1-201) was previously reported from the transcriptome data of 15 Caucasian tissues [33]. We then confirmed a similar expression pattern of GATA6-AS1-201 compared with Moshe during the in vitro differentiation of hESCs to cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6G). Moreover, RNA expressions of two putative Moshe orthologues in pig were evaluated from major pig organs and only ENSSSCT00000038071 which retained conserved regions of 170 bp to 360 bp showed a high expression level in heart tissues. Taken together, our results presenting the conservation of expression profiles during development as well as in tissue-wise comparison indicate that Moshe and its orthologues may have a crucial role in heart development.

In conclusion, we identified a LncRNA, Moshe, spatiotemporally expressed in cardiac differentiation and revealed that Moshe plays an important role in cardiac development by enhancing Nkx2.5, resulting in repressed Isl1 expression that is directly associated with SHF genes’ regulatory network. The cross-species conservation of Moshe allows us to have a better understanding of heart development regulation and diseases including a common congenital heart disease, ASD. Future studies using Moshe knock-out mouse models and co-staining Moshe with SHF will provide conclusive evidence of its role in cardiac development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eun-Young Kim, at the Institute of Reparative Medicine and Population, Medical Research Center, Korea and M.Y. Lee from Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyungpook National University, Korea for providing the Human ESC cells differentiated to cardiomyocyte cells.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT National Research Foundation of Korea #2016M3A9B6026771, #2014M3A9D5A01073598 and #2019R1F1A1061923.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing conflicts of interests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.Cho, N.J.Kim, K.H.Lee; methodology, N.J.Kim, K.H.Lee, Y.S.Son, A.R. Nam,E.H.Moon, J.H.Pyun, J.Y.Park.; investigation, N.J.Kim.; writing-original draft, N.J.Kim.; writing-review & editing, J.Y.Cho, K.H.Lee.; funding acquisition, J.Y.Cho resources, Y.J.Lee, J.S.Kang, Y.S.Son.; supervision, J.Y.Cho

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

References

- [1].Briggs LE, Kakarla J, Wessels A.. The pathogenesis of atrial and atrioventricular septal defects with special emphasis on the role of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion. Differentiation. 2012;84(1):117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kelly RG, Buckingham ME, Moorman AF.. Heart fields and cardiac morphogenesis. Csh Perspect Med. 2014;2–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jia GS, Preussner J, Chen X, et al. Single cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analysis of cardiac progenitor cell transition states and lineage settlement. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dorn T, Goedel A, Lam JT, Haas J, Tian Q, Herrmann F, et al. Direct nkx2-5 transcriptional repression of isl1 controls cardiomyocyte subtype identity. Stem Cells. 2015; 33. 1113-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van der Linde D, Konings EEM, Slager MA, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2241–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Anderson KM, Anderson DM, McAnally JR, et al. Transcription of the non-coding RNA upperhand controls Hand2 expression and heart development. Nature. 2016;539(7629):433–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Garcia-Padilla C, Aranega A, Franco D. The role of long non-coding RNAs in cardiac development and disease. AIMS Genet. 2018;5:124–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang WJ, Niu ZY, Wang Y, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of atrial septal defect identifies dysregulated genes during heart septum morphogenesis. Gene. 2016;575(2):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wamstad JA, Alexander JM, Truty RM, et al. Dynamic and coordinated epigenetic regulation of developmental transitions in the cardiac lineage. Cell. 2012;151(1):206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jeong MH, Leem YE, Kim HJ, Kang K, Cho H, Kang JS. A Shh coreceptor Cdo is required for efficient cardiomyogenesis of pluripotent stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016;93:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim YY, Ku JB, Liu HC, et al. Ginsenosides may enhance the functionality of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in vitro. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:1312–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Choe MS, Yeo HC, Bae CM, et al. Trolox-induced cardiac differentiation is mediated by the inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Biol Int. 2019;43(12):1505–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chu C, Quinn J, Chang HY. Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP). JOVE-J Vis Exp. 2012;61. 10.3791/3912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, et al. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44(4):667–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He S, Zhang H, Liu HH, Zhu H. LongTarget: a tool to predict lncRNA DNA-binding motifs and binding sites via Hoogsteen base-pairing analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015; 31:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Netanely D, Stern N, Laufer I, et al. PROMO: an interactive tool for analyzing clinically-labeled multi-omic cancer datasets. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2019;20:732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gearing LJ, Cumming HE, Chapman R, et al. CiiiDER: a tool for predicting and analysing transcription factor binding sites. Plos One. 2019;14:e0215495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu YJ, Chen S, Zuhlke L, et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970-2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Koutsourakis M, Langeveld A, Patient R, Beddington R, Grosveld F. The transcription factor GATA6 is essential for early extraembryonic development. Development. 1999;126: 723–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maitra M, Koenig SN, Srivastava D, et al. Identification of GATA6 sequence variants in patients with congenital heart defects. Pediatr Res. 2010;68(4):281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhao RO, Watt AJ, Li JX, et al. GATA6 is essential for embryonic development of the liver but dispensable for early heart formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(7):2622–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brewer A, Gove C, Davies A, et al. The human and mouse GATA-6 genes utilize two promoters and two initiation codons. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(53):38004–38016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tian Y, Yuan LJ, Goss AM, et al. Characterization and in vivo pharmacological rescue of a Wnt2-Gata6 pathway required for cardiac inflow tract development. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Skerjanc IS. Cardiac and skeletal muscle development in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9(5):139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Spater D, Hansson EM, Zangi L, et al. How to make a cardiomyocyte. Development. 2014;141(23):4418–4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brown CO, Chi X, Garcia-Gras E, et al. The cardiac determination factor, Nkx2-5, is activated by mutual cofactors GATA-4 and Smad1/4 via a novel upstream enhancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10659–10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Prall OWJ, Menon MK, Solloway MJ, et al. An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell. 2007;128:947–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lien CL, McAnally J, Richardson JA, et al. Cardiac-specific activity of an Nkx2-5 enhancer requires an evolutionarily conserved Smad binding site. Dev Biol. 2002;244:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chi X, Chatterjee PK, Wilson W, et al. Complex cardiac Nkx2-5 gene expression activated by noggin-sensitive enhancers followed by chamber-specific modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13490–13495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stefanovic S, Barnett P, van Duijvenboden K, et al. GATA-dependent regulatory switches establish atrioventricular canal specificity during heart development. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Camacho P, Fan H, Liu Z, et al. Large mammalian animal models of heart disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2016;3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang L, Salgado-Somoza A, Vausort M, et al. A heart-enriched antisense long non-coding RNA regulates the balance between cardiac and skeletal muscle triadin. Bba-Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Song GX, Shen YH, Ruan ZB, et al. LncRNA-uc.167 influences cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation of P19 cells by regulating Mef2c. Gene. 2016;590:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhu PP, Wu JY, Wang YY, et al. LncGata6 maintains stemness of intestinal stem cells and promotes intestinal tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:1134-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Neumann P, Jae N, Knau A, et al. The lncRNA GATA6-AS epigenetically regulates endothelial gene expression via interaction with LOXL2. Nat Commun. 2018;9:237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liang XQ, Wang G, Lin LZ, et al. HCN4 dynamically marks the first heart field and conduction system precursors. Circ Res. 2013;113:399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Espinoza-Lewis RA, Yu L, He FL, et al. Shox2 is essential for the differentiation of cardiac pacemaker cells by repressing Nkx2-5. Dev Biol. 2009;327:376–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Christoffels VM, Hoogaars WMH, Tessari A, et al. T-box transcription factor Tbx2 represses differentiation and formation of the cardiac chambers. Dev Dynam. 2004;229:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Habets PEMH, Moorman AFM, Clout DEW, et al. Cooperative action of Tbx2 and Nkx2.5 inhibits ANF expression in the atrioventricular canal: implications for cardiac chamber formation. Gene Dev. 2002;16:1234–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Harrelson Z, Kelly RG, Goldin SN, et al. Tbx2 is essential for patterning the atrioventricular canal and for morphogenesis of the outflow tract during heart development. Development. 2004;131:5041–5052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dupays L, Kotecha S, Angst B, et al. Tbx2 misexpression impairs deployment of second heart field derived progenitor cells to the arterial pole of the embryonic heart. Dev Biol. 2009;333:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Herrmann F, Bundschu K, Kuhl SJ, et al. Tbx5 overexpression favors a first heart field lineage in murine embryonic stem cells and in Xenopus laevis Embryos. Dev Dynam. 2011;240:2634–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ritter N, Ali T, Kopitchinski N, et al. The lncRNA locus handsdown regulates cardiac gene programs and is essential for early mouse development. Dev Cell. 2019;50:644-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nakashima Y, Yanez DA, Touma M, et al. Nkx2-5 suppresses the proliferation of atrial myocytes and conduction system. Circ Res. 2014;114:1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Xu YJ, Qiu XB, Yuan F, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of NKX2.5 mutations in patients with congenital atrial septal defect and atrioventricular block. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:2247–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dorn T, Goedel A, Lam JT, et al. Direct Nkx2-5 transcriptional repression of Isl1 controls cardiomyocyte subtype identity. Stem Cells. 2015;33(4):1113–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Colombo S, de Sena-Tomas C, George V, et al. Nkx genes establish second heart field cardiomyocyte progenitors at the arterial pole and pattern the venous pole through Isl1 repression. Development. 2018;145:dev161497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rivera-Feliciano J, Tabin CJ. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev Biol. 2006;295(2):580–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Trivedi CM, Zhu WT, Wang QH, et al. Hopx and Hdac2 interact to modulate Gata4 acetylation and embryonic cardiac myocyte proliferation. Dev Cell. 2010;19(3):450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.