Abstract

During diabetes mellitus, advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are major contributors to the development of alterations in cerebral capillaries, leading to the disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Consequently, this is often associated with an amplified oxidative stress response in microvascular endothelial cells. As a model to mimic brain microvasculature, the bEnd.3 endothelial cell line was used to investigate cell barrier function. Cells were exposed to native bovine serum albumin (BSA) or modified BSA (BSA-AGEs). In the presence or absence of the antioxidant compound, N-acetyl-cysteine, cell permeability was assessed by FITC-dextran exclusion, intracellular free radical formation was monitored with H2DCF-DA probe, and mitochondrial respiratory and redox parameters were analyzed. We report that, in the absence of alterations in cell viability, BSA-AGEs contribute to an increase in endothelial cell barrier permeability and a marked and prolonged oxidative stress response. Decreased mitochondrial oxygen consumption was associated with these alterations and may contribute to reactive oxygen species production. These results suggest the need for further research to explore therapeutic interventions to restore mitochondrial functionality in microvascular endothelial cells to improve brain homeostasis in pathological complications associated with glycation.

Keywords: diabetes, advanced glycation end-products, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, mitochondria

Introduction

Cerebral homeostasis is dependent on the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a highly specialized vascular interface separating the blood compartment from the brain parenchyma. Brain microvascular endothelial cells play a key role in maintaining BBB cohesion through the expression of tight junction proteins (Luissint et al., 2012). In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the BBB is altered by the associated chronic hyperglycemia and the advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) formed as a result of non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation reactions (Prasad et al., 2014; Shahriyary et al., 2018). AGEs-associated endothelial oxidative stress represents a central element in vascular BBB lesions resulting in increased permeability and allowing for entry of potentially neurotoxic substances (Liu et al., 2017; Niiya et al., 2012). These substances can be associated with cerebral dysfunction often characterized in humans by cognitive declines, dementia, or psychiatric complications (Huber, 2008). In many of these neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Kawamura et al., 2012; Saedi et al., 2016), diabetes is a comorbidity. This adds significant health concerns in that the diabetic component can compromise vascular integrity and in the case of cerebral ischemia following a stroke it can lead to hemorrhagic complications (Ergul et al., 2012; Venkat et al., 2017).

Previous investigations on BBB cell-based models have shown the involvement of AGEs-linked endothelial oxidative stress to cell barrier disruption (Freeman and Keller, 2012; Liu et al., 2017; Niiya et al., 2012). However, from these studies little is known regarding the role of mitochondria as a possible source of reactive oxygen species (ROS). There is evidence that mitochondria play a role in BBB stability (Doll et al., 2015) and mitochondrial metabolism is known to change with diabetes and neurodegeneration (Pugazhenthi et al., 2017). However, for many years mitochondria were neglected in studies on endothelial cells because of their proposed minor contribution in ATP production (Davidson and Duchen, 2007) even though the mitochondrial content of BBB endothelial cells is greater than that of cells present in other capillary beds (Brosnan and Claudio, 1998; Oldendorf et al., 1977). Thus, one could assume that examining alterations in mitochondrial metabolism in the endothelial cells of the BBB would significantly contribute to our understanding of physiology and pathophysiology of the the brain microvasculature.

A major factor associated with chronic hyperglycemia are the AGEs. These compounds are formed with oxidative reactions and have been demonstrated to induce an oxidative stress response in endothelial cells (Dobi et al., 2019; Paradela-Dobarro et al., 2016). One accepted in vitro method to assess the effects of AGEs is exposure to isolated AGEs (Patche et al., 2017). In patients with diabetes, the structure and function of the most abundant protein in plasma, albumin (35–50 g/L) (Peters, 1996), has been shown to be significantly impaired (Baraka-Vidot et al., 2015; Guerin-Dubourg et al., 2012). This protein has a 19 days half-life and shows vulnerability to glycoxidation (Rondeau and Bourdon, 2011). To examine the potential association between alterations in mitochondrial respiration and endothelial dysfunction, the murine endothelial cell line, bEnd.3 was used as an in vitro model for evaluating BBB function, especially the paracellular barrier (Watanabe et al., 2013). The effect of albumin AGEs was studied on cell barrier permeability, redox homeostasis and mitochondrial respiration. The findings demonstrated a relationship between these three parameters in brain microvascular endothelial cells exposed to AGEs.

Material and methods

Materials

Bicinchoninic acid (BCA), methylglyoxal (MGO), crystal violet, 2–4 Dinitrophenol (DNP), fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (FITC-Dextran), mannitol, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), HEPES, oligomycin, F1F0-ATP synthase inhibitor, rotenone, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), antimycin A, superoxide dismutase (SOD), 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonate (DTNB), xanthine, xanthine oxidase, cytochrome c, dichlorodihydrofluorescein-diacetate (H2DCF-DA) and 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Preparation of AGEs

Native and modified bovine serum albumin (BSA and BSA-AGEs respectively) were prepared as previously described (Dobi et al., 2019): BSA (fatty acid-poor, endotoxin-free, Calbiochem #126579) was prepared at 40 g/L in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.2M, pH 7.4) and incubated 9 days at 37°C in the dark in the presence or absence of 10 mM methylglyoxal under sterile conditions and with gentle agitation. After AGEs formation, unincorporated methylglyoxal was removed by extensive dialysis against fresh PBS. Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (BCA, Sigma) and BSA and BSA-AGEs were stored at −80°C until time of assay. Both BSA and BSA-AGEs samples have been previously well-characterized (Dobi et al., 2019). BSA-AGEs exhibited higher levels of glycation and carbonylation and contained in particular more MG-H1, argpyrimidine and imidazolone B AGE-adducts than BSA (Dobi et al., 2019).

Cell culture

The murine immortalized bEnd.3 cerebral microvascular endothelial cell line was obtained from the American Culture Collections (ATCC®-CRL-2299TM). bEnd.3 cells were maintained in high-glucose (4.5 g/L) DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (56°C, 30 min), 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, at 37°C. At 90–100% confluency, medium was removed and cells were equilibrated in serum-free DMEM. After 24 h, medium was removed and cells were exposed for 1 h or 24 h to either native BSA or BSA-AGEs diluted in serum-free DMEM at 50 μM or equivalent volume of PBS (control) and in presence or absence of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM) or 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP, 0.25 μM to 100 μM). This pathological concentration model was well characterized and previously reported (Dobi et al., 2019; Patche et al., 2017).

Cell viability

Confluent bEnd.3 cells (100 000 cells / 96-well plate) were exposed to vehicle, BSA or BSA-AGEs for 24 h. Cells were washed with PBS followed by the addition of 50 μL 0.1% crystal violet solution for 10 min. The cells were carefully rinsed three times and 200 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate were added to each well to solubilize the dye and absorbance read at 570nm. Individual absorbance values under each condition were calculated as the mean response of vehicle exposed cells.

Measurement of endothelial barrier permeability

Endothelial barrier permeability was assayed on endothelial bEnd.3 cells. Cells (3×105) were seeded on Millicell® 12-well hanging cell culture inserts (PET membrane with 0.4 μm pores). The measurement of endothelial barrier permeability was performed on confluent cells using dextran (4 kDa and 70 kDa) labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), before and after treatments with vehicle control (PBS), native BSA or modified BSA (BSA-AGEs) at 50 μM, for 24h. Mannitol was used at the concentration of 1.4 M as a hyperosmotic solution to induce the opening of the endothelial barrier (positive control) (Ikeda et al., 2002; Rapoport, 2000). Dextran (4 kDa and 70 kDa) was prepared at 0.385 mg/mL in serum-free RPMI 1640 (without phenol red) and 800 μL of the solution were added on cells (apical chamber), after a washing step with PBS. The basolateral chamber was composed of serum-free RPMI 1640 (without dextran at the beginning of the test). Ten minutes after the addition of dextran in the apical chamber, the inserts were placed in another well containing fresh RPMI (without dextran) for an additional ten minutes. The inserts were then removed and aliquots of RPMI that was in the basolateral chamber were used to measure the intensity of fluorescence of FITC (reflecting the quantity of dextran that crossed the endothelial barrier). The excitation/emission wavelength was set at 485/520 nm for FITC fluorescence (FLUOstar Omega, BMG Labtech). Results were expressed as variation of FD4 or FD70 quantities (μg) corresponding to the difference of FITC-dextran quantity measured after and before cells’ stimulation.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

Cells were plated in 96-well plate (0.1×106 cells/well), allowed to acclimate for 24 h followed by exposure to vehicle, BSA or BSA-AGEs for 1 or 24 h and also to DNP (0.25 μM to 100 μM). Cells were washed with PBS then incubated at 37°C (in 5% CO2 incubator) for 30 min with 10 μM H2DCF-DA in serum-free DMEM. Cells were washed with PBS and fluorescence intensity (485/520 nm) was measured by the FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech) using a well-scanning mode (4×4).

Cellular oxygen consumption rate

Oroboros

Endothelial bEnd.3 cells were cultured in T25 flasks. After treatment (BSA or BSA-AGEs in presence or absence of N-acetyl cysteine), they were washed with PBS, collected with trypsin/EDTA and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min, at room temperature. Subsequently, cell pellets were suspended in 500 μL serum-free high-glucose DMEM and divided in two new cellular suspensions containing about 2×106 cells. Basal oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were continuously measured on whole cells at 37°C, using a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Oroboros Oxygraph-2k, Oroboros Instruments). The respiration medium consisted of serum-free DMEM buffered with 10 mM HEPES in a final volume of 2.1 mL. For calibration of the polarographic oxygen sensor and measurement of background oxygen consumption, the respiration medium without biological sample was added into the O2k-Chamber. For each experimental condition, OCR was measured in the presence or absence of the F1F0-ATP synthase inhibitor, oligomycin (0.1 μM), the protonophoric uncoupler, dinitrophenol (300–400 μM) and the inhibitor of mitochondrial complex III, antimycin A (0.1 μM). OCR values specifically related to mitochondria were calculated by subtracting non-mitochondrial respiration (in the presence of antimycin A). Data were expressed as picomoles O2 consumed by cells per second and per milligram of cell protein determined by BCA.

Seahorse Bioanalyzer

Cells were expanded in tissue culture flasks, trypsinized, and replated for analysis. XF24 24-well Seahorse plates were seeded with bEnd.3 cells at a density of 25 000 cells/well and allowed to acclimate for 24 h under normal incubation conditions. The medium was changed to DMEM without FCS and the cells were exposed to BSA or BSA-AGEs for 18 h under normal incubation conditions. The medium was then changed to Seahorse assay medium and the cells were incubated at 37°C in a CO2-free atmosphere for 1 h prior to assay. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were detected in quintuplicate across 3 readings in presence of sequential additions of oligomycin (1 μM), FCCP (2.5 μM), and rotenone (3 μM). For normalization, at the end of the measurement, cell lysate protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay as previously described (Dranka et al., 2011).

Protein isolation from bEnd.3 cells and enzymatic assays

Following exposure, bEnd.3 cells were washed with PBS, scraped from the plate, centrifuged (2 000 rpm for 5 min), and the cell pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer (Tris-HCl 50 mM, EDTA 1 mM, Triton 0,1%, pH 7.4). The lysis was subjected to five cycles of fast freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by thawing in a 37°C water bath. Then, the lysates samples were stored at −80°C until assay.

To determine citrate synthase activity, a 10 μL aliquot (at about 0.5 μg/μL of protein) of the lysate was combined with 180 μL reaction mixture (50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and 0.5 mM oxaloacetate). This allows for a reaction with citrate synthase in the lysate. The reaction product was detected in a plate reader at 412 nm for 3 min, at 37°C. Enzyme activity was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 13,600 M−1 cm−1 at 412 nm. Results were expressed as nanomoles of DTNB reduced/min/mg protein calculated as a percent of vehicle control.

Manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD or SOD2) activity was determined using the cytochrome c reduction assay. In this method, superoxide radicals generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system reduce cytochrome c, thereby leading to an increase in absorbance at 560 nm. 20 μL aliquot (about 20 μg of protein) of the lysates was combined with 170 μL reaction mixture (xanthine oxidase, xanthine (0.5 mM), cytochrome c (0.2 mM), KH2PO4 (50 mM, pH 7.8), EDTA (2 mM) and NaCN (1 mM)). The reaction was monitored in a microplate reader at 560 nm for 1 min, at 25°C. Mn-SOD activity was calculated using a calibration standard curve of SOD (up to 6 units/mg) from the slope of the linear portion of the absorbance. Results were expressed as international catalytic units per milligram of cell protein and then normalized in percentage versus the vehicle control condition.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments conducted in duplicate or triplicate. Statistical significance was determined using Student t-test for two groups comparisons or a one-way or two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for comparisons of multiple times or conditions (Graph Pad Prism). Detection of outliers and variance homogeneity (Kolmogrov-Smirnov) was performed prior to statistical analysis. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

BSA-AGEs induce an increase in bEnd.3 cells permeability

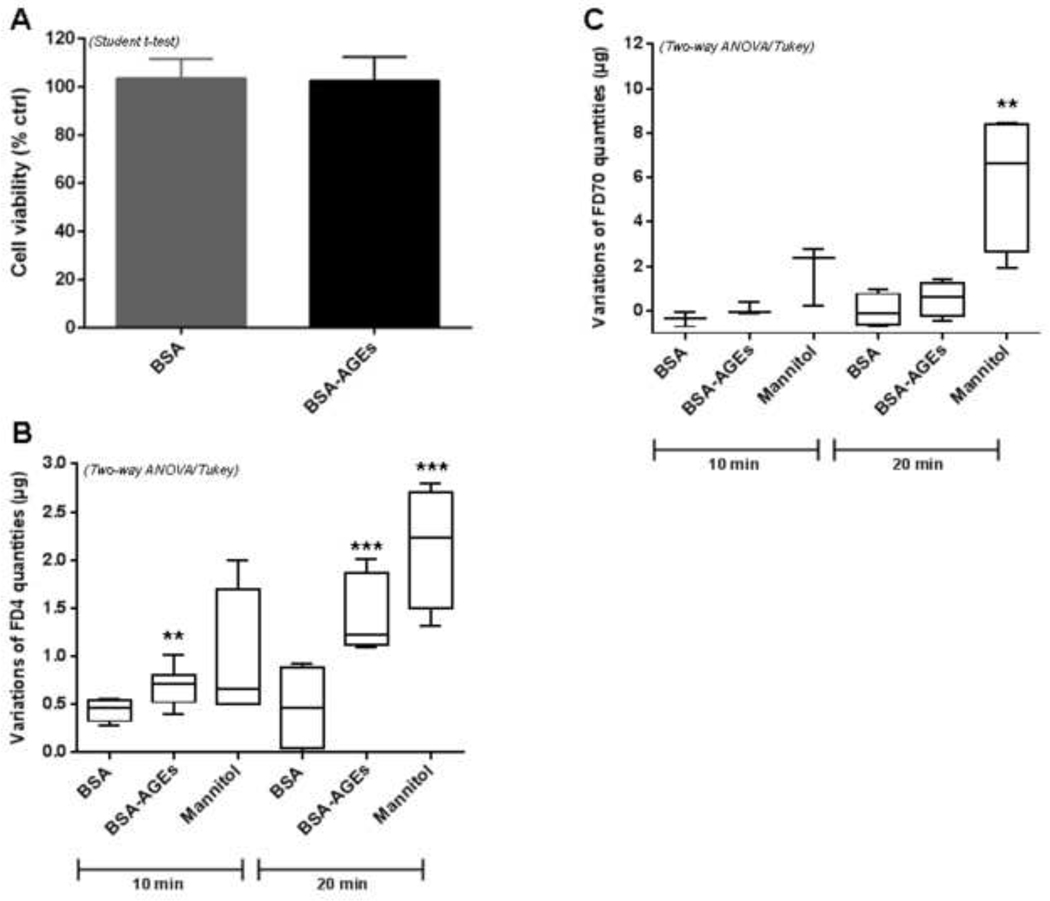

Before investigating the impact of methylglyoxal-modified bovine serum albumin (BSA-AGEs) on bEnd.3 cell barrier permeability (i.e. on a physiological parameter) we checked its potential toxicity in our experimental condition. The crystal violet assay showed that BSA-AGEs did not affect significantly cell viability of bEnd.3 cells (Fig. 1A) and therefore could be used for a cell exposition of at least 24 h. The endothelial permeability was investigated by using an intermediate (4 kDa) and a large-size (70 kDa) fluorescent tracer (FITC-dextran).

Fig 1: BSA-AGEs increase endothelial barrier permeability.

A) Cell viability was determined by crystal violet cell adherence assay after treatments with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM for 24h. Bars represent the mean ± SD cell number in each condition as a percentage of control (n = 4).

Permeability was assayed on bEnd.3 cells using B) 4 kDa FITC-dextran (FD4) and B) 70 kDa FITC-dextran (FD70) before and after treatments with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM for 24 h. Mannitol diluted in DMEM (1.4 M) was used as positive control. The intensity of FITC fluorescence was measured in each basolateral chamber 10 min and 20 min after the addition of FD4 or FD70 in the apical chamber. Bars represent the mean ± SD of the variations of dextran quantities (μg) having crossed cell barrier (n = 4–5). *Effect of BSA-AGEs or Mannitol (vs. BSA) **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 determined by Tukey’s post hoc analysis following a significant two way ANOVA (for B and C).

Mannitol at 1.4 M (osmotic regulator) was used as positive control to induce an osmotic opening of endothelial barrier. The marked increase in FD4 or FD70 in the basolateral chamber for cells exposed to mannitol, after 20 min of dextran exposition, allowed us to show the validity of the assay and the robustness of cell response (Fig. 1B–C). After treatment with BSA-AGEs followed by dextran exposition, a greater quantity of FD4 in the basolateral chamber was measured, as compared to native BSA treatments (Fig. 1B: + 55% and + 210% after 10 min and 20 min exposition, respectively, p < 0.01). The increase of the large-size tracer FD70 observed in the basolateral compartment of cells treated with BSA-AGEs after 10 min or 20 min of dextran exposition did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1C). It should also be noted that 24 h treatment with BSA alone does not affect the monolayer permeability (data not shown). These data suggest that endothelial barrier permeability is increased upon BSA-AGEs treatment.

BSA-AGEs induce intracellular bEnd.3 oxidative stress with increase in SOD2 activity

As oxidative stress is well characterized to be involved in endothelial cell barrier disruption (Freeman and Keller, 2012), we monitored intracellular ROS formation with H2DCF-DA fluorescent probe that mainly detects hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Fig. 2/Fig. S1). Significant enhancements in ROS production were observed in bEnd.3 cells treated in the presence of BSA-AGEs for a short-term exposure (1 h) (+ 47%, p < 0.01 vs. BSA) and also for a long term exposure (24 h) (+ 56%, p < 0.001 vs. BSA) (Fig. 2A). In light of these results, confluent bEnd.3 cells were thus subjected to a marked and prolonged oxidative stress in the presence of BSA-AGEs. In the presence of NAC (0.5 mM), an antioxidant compound known to react with H2O2 and H2O2-derived ROS, ROS production was significantly reduced for BSA-treated cells (− 44%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA), as well as for BSA-AGEs-treated cells (− 25%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA-AGEs) (Fig. 2B) as attested by the decrease in DCF fluorescence.

Fig. 2: BSA-AGEs induce an increase in bEnd.3 oxidative stress associated with endothelial barrier permeability which could be partially reduced by N-acetyl cysteine.

ROS levels were determined with H2DCF-DA probe in bEnd.3 cells treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM A) for 1h or 24h, and B) for 1h in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). Bars represent the mean ± SD of 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence as a percentage of vehicle (n = 3–4). C) Permeability was assayed on bEnd.3 cells using 4 KDa FITC-Dextran (FD4) before and after treatments with BSA or BSA-AGEs (50 μM) for 24h, in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM NAC. The intensity of fluorescence from FITC was measured in each basolateral chamber 10 min after the addition of FD4 in the apical chamber. Bars represent the mean ± SD of the variations of dextran quantities having crossed cell barrier (n = 4–5). D) SOD2 activity was determined in lysates from cells previously treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs (50 mM) for 24 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of the enzyme activity (expressed as % of international catalytic unit in regard to vehicle condition (n = 3).

*Effect of BSA-AGEs (vs. BSA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. #Effect of NAC (vs. BSA-AGEs). #p < 0.05 determined by Tukey’s post hoc analysis following a significant two way ANOVA (for A, B and C) or by a Student t-test (for D).

To confirm the link between cell barrier permeability and oxidative stress in our model, we next performed FD4 assay in the presence of NAC. The antioxidant significantly decreased endothelial barrier permeability for BSA-AGEs treated cells (− 45%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA-AGEs) (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrate that BSA-AGEs-induced increase in endothelial barrier permeability is due, at least in part, to oxidative stress, and not to an alteration in cell viability.

Given that mitochondria could be involved in oxidative stress, SOD2 activity was assessed in bEnd.3 cells. This protein is a key antioxidant enzyme in mitochondrial matrix, modulating ROS formation in these organelles (Storz et al., 2005). In our experimental condition (after 24 h treatment), a significant increase in SOD2 activity was evidenced between BSA and BSA-AGEs conditions (+38%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA) (Fig. 2D).

BSA-AGEs impaired bEnd.3 mitochondrial metabolism

To further investigate the mitochondrial aspect related to oxidative stress, we studied the respiratory metabolism of bEnd.3 cells using two different methods of analysis: the Oxygraph-2k high-resolution respirometer and the high-throughput Seahorse Extracellular Flux (XF) Analyzer.

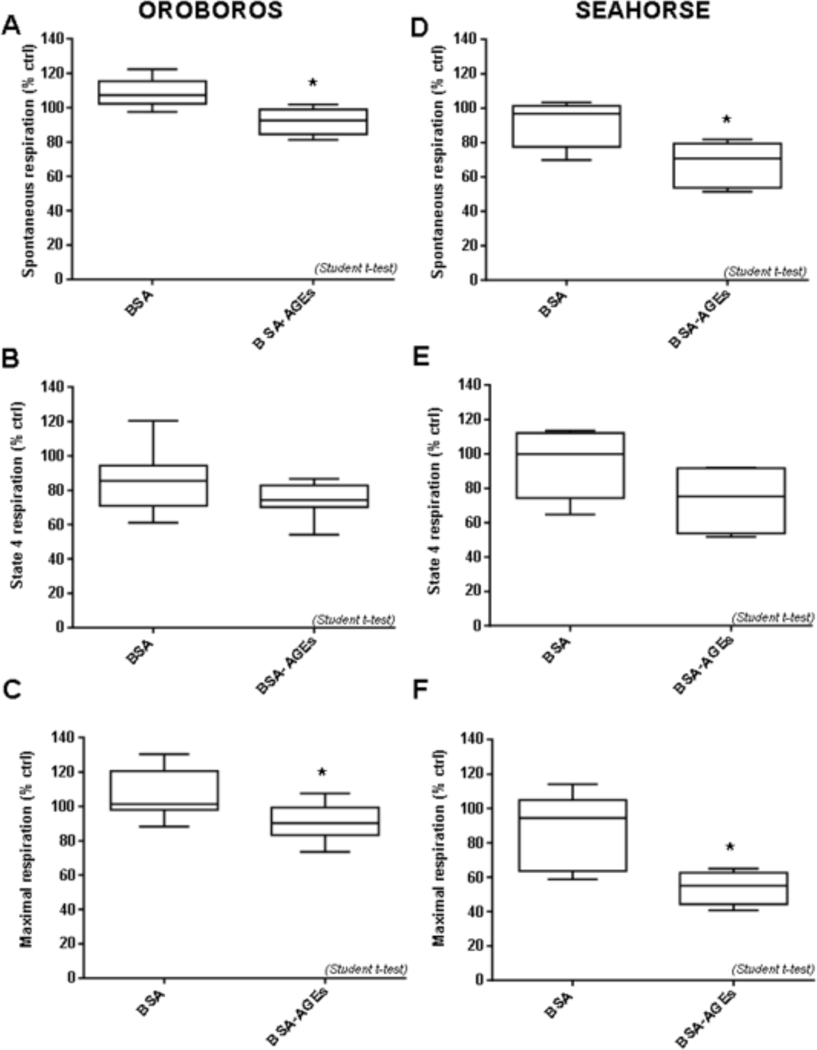

The different type of mitochondrial respiration (oxygen consumption) (spontaneous, state 4 and maximal respirations) investigated with Oroboros are shown in Fig. 3A–C. Basal mitochondrial (phosphorylating state) and maximal (with DNP) respirations were found to be significantly reduced after BSA-AGEs stimulation (− 18%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA) (Fig. 3A) and (− 15%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA) (Fig. 3C), respectively. Regarding state 4 respiration (non phosphorylating state in the presence of oligomycin), no difference was recorded between BSA and BSA-AGEs conditions (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with the Seahorse analyzer (Fig. 3D–F). Indeed, a quite equivalent reduction in basal respiration was observed (− 26%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA) (Fig. 3D) and in maximal respiration (− 38%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA) (Fig. 3F) for BSA-AGEs treated cells in comparison BSA condition. However, the decrease in the state 4 respiration between BSA and BSA-AGEs conditions (−15% vs. BSA) failed to reach statistical significance (Fig. 3E). Taken together, our data reveal that, using either the Oroboros or the Seahorse, an alteration of mitochondrial respiration is evidenced in BSA-AGEs condition, as compared to native BSA condition.

Fig. 3: BSA-AGEs alter mitochondrial respiratory parameters of bEnd.3 cells.

Oxygen consumption by bEnd.3 cells was recorded 24h after treatments with BSA or BSA-AGEs (50 μM) for 24h. A-C: measurement by OROBOROS Oxygraph-2k; A) Spontaneous mitochondrial respiration. B) state 4 respiration (in the presence of oligomycin) and C) maximal respiration (in the presence of DNP). D-F: measurement by Seahorse XF Analyzer; D) Spontaneous mitochondrial respiration. E) state 4 respiration (in the presence of oligomycin) and F) maximal respiration (in the presence of DNP),. Bars represent the mean ± SD of oxygen consumption in percentage versus vehicle condition (n = 6–8). *Effect of BSA-AGEs (vs. BSA). *p < 0.05 determined by a Student t-test.

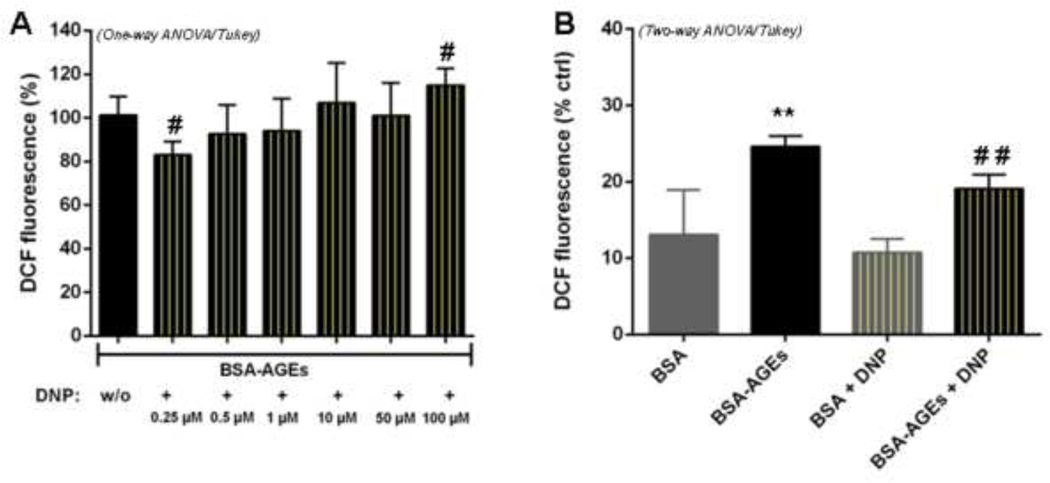

To confirm the involvement of mitochondria in BSA-AGEs-enhanced oxidative stress, we co-incubated cells with different concentrations of dinitrophenol (DNP). In our experimental conditions, DNP is applied to bEnd.3 cells only for 45 minutes and at low concentrations (0.25 to 100 μM) as compared to the maximal (and potentially toxic) concentration that is required to achieve maximal mitochondrial respiration (about 400 μM). In this condition, DNP did not exert significant changes in cell viability (see Fig. S2). Indeed, low doses of artificial uncoupler have been demonstrated to decrease mitochondrial superoxide formation by dissipating the electrochemical potential gradient, thereby accelerating the rate of electron transfer (Kariman et al., 1986). As expected, DCF fluorescence was modulated by DNP. It was decreased at low concentrations of the compound, particularly at 0.25 μM (− 17%, p < 0.05 vs. control cells without DNP), and amplified at higher concentrations, particularly at 100 μM (+ 16%, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). This mitochondrial uncoupler, used at 0.25 μM, did not have any significant effect in DCF fluorescence for native BSA- treated cells and induce a marked decrease in ROS production for BSA-AGEs- treated cells (− 23%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA-AGEs) (Fig. 4B). These results suggest a specific role of mitochondria in ROS production during BSA-AGEs treatment.

Fig. 4: DNP modulates ROS production in BSA-AGEs-treated cells.

A) ROS levels were determined with H2DCF-DA probe in bEnd.3 cells treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM for 24h, and then co-incubated with or without (w/o) DNP (0.25 to 100 μM) for an additional 45 min. B) ROS levels were measured in cells treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM for 24h, and then co-incubated with or without DNP at 0.25 μM for an additional 45 min. Bars represent the mean ± SD of 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence normalized in percentage (n = 3–4). *Effect of BSA-AGEs (vs. BSA). **p < 0.01. #Effect of DNP (vs. BSA-AGEs). #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 determined by Tukey’s post hoc analysis following a significant one way ANOVA (for A) or a two way ANOVA (for B).

NAC recovered altered mitochondrial respiration of bEnd.3 cells upon BSA-AGEs stimulation

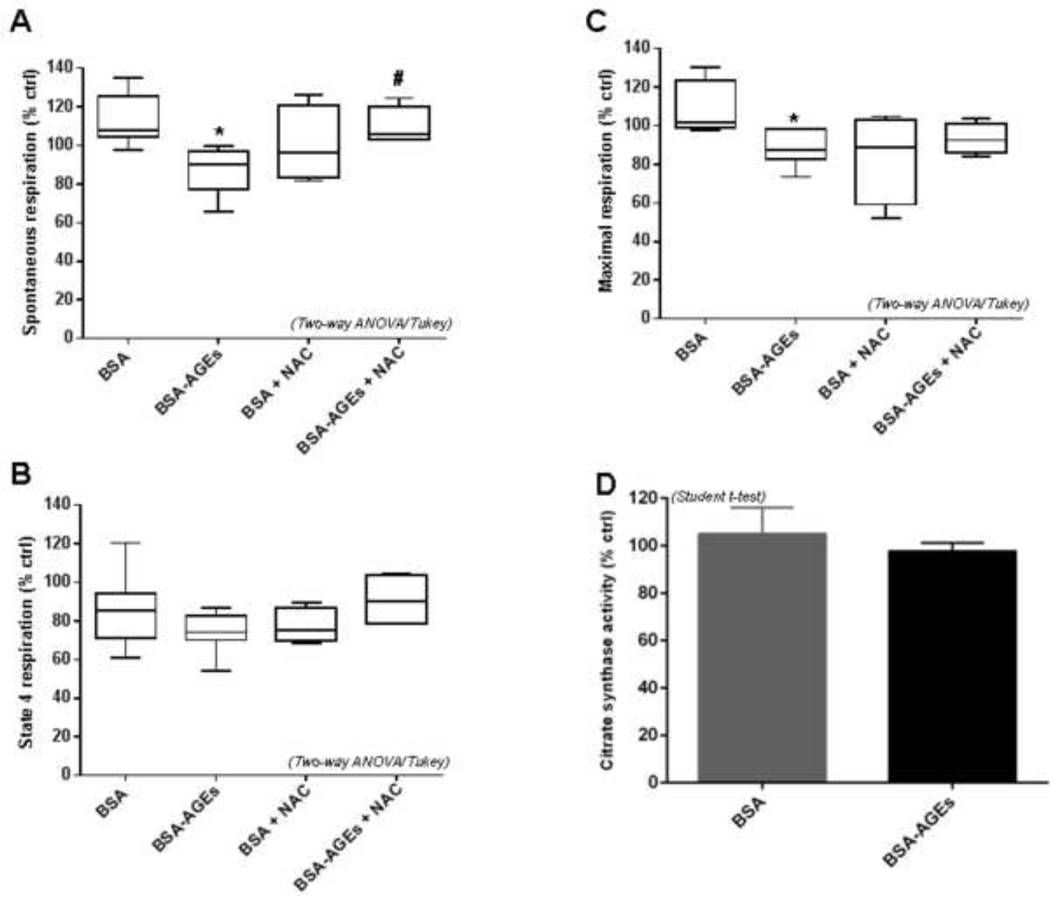

As mitochondria contribute to oxidative stress in BSA-AGEs-treated bEnd.3 cells, we sought to determine the cause of the decreased oxygen consumption in these conditions. We hypothesized that oxidative stress itself could be responsible for this phenomenon. To confirm this hypothesis, mitochondrial respiration was assessed using the Oroboros method on bEnd.3 cells treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs and in the presence of NAC (0.5 mM). NAC did not change significantly spontaneous mitochondrial respiration in BSA condition. In cells co-incubated with BSA-AGEs and NAC, this basal respiratory state was found to be markedly enhanced in comparison with cells only stimulated with BSA-AGEs (+ 16%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA-AGEs) (Fig. 5A). Thus, the reduction of this parameter initially recorded between BSA and BSA-AGEs conditions was attenuated by an antioxidant treatment. The effect of NAC on state 4 respiration was less obvious, as long as the increase in oxygen consumption in the condition BSA-AGEs + NAC, as compared to the condition BSA-AGEs (+ 4%) did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5B). The tendency of BSA-AGEs to lessen the proton leak relative to native BSA was inhibited by NAC. No major impact of NAC on maximal respiration was observed. However, the significant decrease initially detected after BSA-AGEs stimulation (−15%, p<0.05 vs. BSA) was no longer observed for cells upon co-exposure to NAC (i.e. no difference in oxygen consumption between the conditions BSA + NAC and BSA-AGEs + NAC) (Fig. 5C). Given that no variation of citrate synthase activity (a well-accepted indicator of cell mitochondrial content (Baret et al., 2018; Larsen et al., 2012) as evidenced between the different conditions (Fig. 5D), our findings confirm the role of oxidative stress in the alteration of mitochondrial respiratory parameters of bEnd.3 cells.

Fig. 5: BSA-AGEs induced bEnd.3 oxidative stress was rather due to reduced mitochondrial respiration.

Oxygen consumption by bEnd.3 cells was recorded 24h after treatments with BSA or BSA-AGEs at 50 μM for 24h, in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM NAC. A) Spontaneous mitochondrial respiration, B) state 4 respiration and C) maximal respiration were measured in each condition using OROBOROS Oxygraph-2k. D) Biomarker of mitochondrial content, citrate synthase activity was determined in lysates from bEnd.3 cells 24h after treatment. Bars represent the mean ± SD of the studied parameter in percentage versus vehicle condition (n = 6–8). E) SOD2 activity was determined in lysates from cells treated with BSA or BSA-AGEs (50 mM) for 24 h, in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM NAC. Bars represent the mean ± SD of the enzyme activity in percentage versus vehicle condition (n = 3). *Effect of BSA-AGEs (vs. BSA). *p < 0.05. #Effect of NAC (vs. BSA-AGEs). #p < 0.05 determined by Tukey’s post hoc analysis following a two way ANOVA (for A, B, C and E).

Not surprisingly, we found a modulation of SOD2 activity when bEnd.3 cells were co-incubated with BSA-AGEs and NAC. Indeed, the significant increase in SOD2 activity shown for BSA-AGEs treated cells (+38%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA), was found to be completely lost in presence of NAC (− 40%, p < 0.05 vs. BSA-AGEs) (Fig. 5E). These last results are in accordance with the capacity of NAC to recover the altered mitochondrial respiration during BSA-AGEs stimulation.

Discussion

Thanks to an in vitro model of brain microvasculature (bEnd.3 cells) we demonstrated the involvement of mitochondria in oxidative stress induced with BSA-AGEs exposure. This involvement was evidenced by the conjunction of two phenomena: enhancement of SOD2 activity associated with an altered mitochondrial respiration and decreased ROS intracellular level in the presence of DNP. This impairment of bEnd.3 mitochondria metabolism upon BSA-AGEs-induced intracellular oxidative stress noticeably induces an alteration of the endothelial barrier impermeability. In addition, the role of ROS in the alteration of mitochondrial respiration was clearly evidenced by the analysis of respiratory parameters in the presence of NAC.

In diabetic patients, chronic hyperglycemia is favorable to the formation of AGEs. Elevated concentrations of AGEs derived from serum albumin represent a typical “blood fingerprint” in T2DM (Cohen, 2003). Circulating AGEs can interact with endothelial cells via the RAGE (receptor for AGEs), leading to vascular complications (Wautier et al., 2014). Some residues found in AGEs, such as Nε-carboxymethyl-lysine or hydroimidazolones, are known to bind with the RAGE (Luévano-Contreras et al., 2017). In a previous analysis by MALDI-TOF-MS peptide mapping, we demonstrated that these residues are more abundant in MGO-modified albumin than in the native protein (Dobi et al., 2019). AGEs/RAGE interaction triggers intracellular oxidative stress resulting in the activation of several pathways including p21ras, mitogen activated protein kinases (MAP-kinases) or protein kinase C (PKC) (Cohen et al., 2003; Giacco and Brownlee, 2010).

At the level of BBB microvasculature, oxidative stress generated by AGEs is associated with the disruption of endothelial cells’ cohesion with adverse effects on the function of barrier. We used bEnd.3 cells to reproduce brain microvasculature in vitro and evaluate its permeability with fluorescently labeled tracers, i.e. dextran molecules (non-digestible sugars). Since pinocytosis is a very slow process and transcytosis of dextran has not been reported thus far in endothelial cells, the increased permeability observed in the presence of BSA-AGEs seems to occur via the paracellular route (Frost et al., 2019). Oxidative stress plays a dominant role in this outcome. Indeed, using BSA-AGEs, Niiya et al. showed that a hyperpermeability of endothelial cell monolayers (particularly from brain microvascular cells) to FD4 is a consequence of an excessive production of intracellular superoxide anions (Niiya et al., 2012). Our data indicated that hydrogen peroxide (measured by H2DCF-DA probe) is also involved in this phenomenon. If H2DCF-DA is commonly used for measuring intracellular H2O2, the oxidation of this fluorescent probe by H2O2 is not direct and its reactivity toward other oxidant species, such as hydroxyl radical, carbonate radical, nitrogen dioxide and thiyl radicals could occur (Wojtala et al., 2014). Therefore, H2O2, but also other ROS, are involved in the increased endothelial permeability observed in the presence of BSA-AGEs.

Studies performed on other models of brain microvascular endothelial cells revealed a redistribution of the tight junction proteins occludin, and zonula occludens (ZO) mediated by ROS, leading to a rise in paracellular permeability (Fischer et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004). In a context of hypoxia/reoxygenation, Fischer et al. associated this hyperpermeability with phospholipase C activation and intracellular calcium elevation followed by the phosphorylation of MAP kinases (Fischer et al., 2005). It is well known that the assembly and stabilization of tight junctions is dependent on actin cytoskeleton dynamics. As mentioned by Prasain and Stevens about F-actin, “a tightly controlled balance of polymerization and depolymerization is necessary to maintain cell shape and control the endothelial cell barrier function” (Prasain and Stevens, 2009). Indeed, a recent study on primary mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells reported that ROS derived from the AGEs/RAGE signaling pathway downregulate the expression of actin depolymerizing factor. This modulation was accompanied by a formation of F-actin stress fibers, a decrease in ZO-1 expression and an increase in endothelial permeability (Liu et al., 2017). In vivo investigations conducted on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats support these results, in which enhanced endothelial leakage in the retinal microvasculature is associated with large amounts of F-actin stress fibers (Yu et al., 2005), and the levels of ZO-1 and occluding are reduced in cerebral microvessels (Hawkins et al., 2007). The loss of endothelial tight junction proteins under diabetic conditions has been also related to the expression of others proteins, such as matrix metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), both involved in amplified cell permeability (Hawkins et al., 2007; Shimizu et al., 2013).

In addition to tight junctions, the permeability of the BBB is also regulated by different transporters including efflux and influx transporters. Diabetic situations may affect transporters such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp), low density, lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1, and the insulin transporter alteration (Banks, 2020). As hyperglycemia could lead to AGE, some effects on transporters could involve RAGE activation (Park et al., 2014). As these transporters needs ATP, modification of the ATP production may interfere with these proteins functions (Pahnke et al., 2013).

Although numerous studies described the impact of AGEs on endothelial function, very few of them focused on mitochondria that are potential source of ROS. This is particularly the case for microvascular endothelial cells. In this study, the involvement of mitochondria in BSA-AGEs induced oxidative stress was evidenced by a significant upregulation of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2). If several studies reported an increased SOD activity in diabetic condition (Aouacheri et al., 2015; Seghrouchni et al., 2002), other works rather showed a decrease in this antioxidant activity (Kesavulu et al., 2000; Sundaram et al., 1996). These discrepancies could be attributed to both SOD isoforms, In a previous work we reported a down-regulation of SOD1 activity parallel to up-regulation of SOD2 activity in mouse diabetic liver (Patche et al., 2017). Here, the increase in SOD2 activity suggests a possible adaptive response, probably due to mitochondrial oxidative stress. Oxidative stress can activate several cytoplasmic factors, including NF-κB, p53, mTOR, ERK and p38 MAPKs, which then translocate into the nucleus and induce the expression of SOD2 gene (Candas and Li, 2014).

For investigating the effect of BSA-AGEs on bEnd.3 mitochondrial respiration two different technologies were used: Oroboros and Seahorse. With the Oroboros, a Clark-type oxygen electrode was used, whereas with the Seahorse, fluorescence quenching by oxygen was measured. Moreover, the biological state in which bEnd.3 cells are during the time of analysis was not the same. With Oroboros the measurement was performed on cells suspension while with the Searhose the measurement was made directly on the adherent cells. Here, the investigation with both instruments allows to show a similar alteration of mitochondrial respiration in bEnd.3 cells upon BSA-AGEs condition. This altered mitochondrial oxygen consumption suggests a decrease in the rate of electron transfer along the mitochondrial respiratory chain. This slowing of electron transfer is an outcome that is recognized to promote ROS production.

As regards macrovascular endothelial cells exposed to AGEs, a dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain has been previously reported, in parallel with ROS overproduction (Liu et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017; Sangle et al., 2010). In accordance with our data showing the possible involvement of mitochondria in barrier properties of bEnd.3 cells, Doll et al. (2015) established that maintenance of mitochondrial function is critical to the integrity of the BBB. Using pharmacological inhibitors of mitochondria they showed a disruption in tight junctions (ZO-1) and increased endothelial permeability in bEnd.3 cells. These results were confirmed in a murine model with an epidural application of the mitochondrial toxicant, rotenone (Doll et al., 2015).

In conclusion, we propose a mechanistic scheme in which AGEs induces oxidative stress in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells contributing to vascular hyperpermeability (Fig. 6). Dysfunctional mitochondria can generate high levels of ROS (Kluge et al., 2013) and mitochondria are directly impacted by excessive ROS production. They further contribute to enhance the ROS production through a decrease in oxygen consumption rate. Given that T2DM is a metabolic disease associated with chronic pro-oxidant events, interventions utilizing anti-oxidant strategies to prevent or limit mitochondrial alterations, such as polyphenol-based therapies (Liu et al., 2013) offer a novel therapeutic intervention. Additional consideration can be made to the possible approach of inducting the overexpression of uncoupling proteins (UCPs) that are known to decrease mitochondrial ROS formation and preserve endothelial function (Tang et al., 2014).

Fig. 6:

Proposed model for BSA-AGEs-induced an increase in endothelial cell barrier permeability related to oxidative stress and mitochondrial respiration.

Supplementary Material

Ackowledgement

This work was supported by the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, the Université de La Réunion, by the European Regional Development Funds RE0001897 (EU- Région Réunion -French State national counterpart) and by NIH intramural research funding Z01 ES021164-12 in the Division of National Toxicology Program. AD is supported by a fellowship from the Conseil Régional de La Réunion et l’Europe. We would like to thanks Dr R Cannon and Dr P Ravanan for their reading and input in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests

REFERENCES

- Aouacheri O, et al. , 2015. The investigation of the oxidative stress-related parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Can J Diabetes. 39, 44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, 2020. The Blood-Brain Barrier Interface in Diabetes Mellitus: Dysfunctions, Mechanisms and Approaches to Treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 26, 1438–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraka-Vidot J, et al. , 2015. Glycation alters ligand binding, enzymatic, and pharmacological properties of human albumin. Biochemistry. 54, 3051–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baret P, et al. , 2018. Glycated human albumin alters mitochondrial respiration in preadipocyte 3T3-L1 cells. Biofactors. 43, 577–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan C, Claudio L, Brain microvasculature in multiple sclerosis. In: Pardridge WM, (Ed.), Introduction to the blood-brain barrier: methodology, biology and pathology. Cambridge University Press, cop. 1998., Cambridge; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Candas D, Li JJ, 2014. MnSOD in oxidative stress response-potential regulation via mitochondrial protein influx. Antioxid Redox Signal. 20, 1599–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MP, 2003. Intervention strategies to prevent pathogenetic effects of glycated albumin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 419, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MP, et al. , 2003. Glycated albumin increases oxidative stress, activates NF-kappa B and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and stimulates ERK-dependent transforming growth factor-beta 1 production in macrophage RAW cells. J Lab Clin Med. 141, 242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson SM, Duchen MR, 2007. Endothelial mitochondria: contributing to vascular function and disease. Circ Res. 100, 1128–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobi A, et al. , 2019. Advanced glycation end-products disrupt human endothelial cells redox homeostasis: new insights into reactive oxygen species production. Free Radic Res. 53, 150–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll DN, et al. , 2015. Mitochondrial crisis in cerebrovascular endothelial cells opens the blood-brain barrier. Stroke. 46, 1681–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranka BP, et al. , 2011. Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic Biol Med. 51, 1621–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergul A, et al. , 2012. Cerebrovascular complications of diabetes: focus on stroke. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 12, 148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, et al. , 2005. H2O2 induces paracellular permeability of porcine brain-derived microvascular endothelial cells by activation of the p44/42 MAP kinase pathway. Eur J Cell Biol. 84, 687–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LR, Keller JN, 2012. Oxidative stress and cerebral endothelial cells: regulation of the blood-brain-barrier and antioxidant based interventions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1822, 822–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost TS, et al. , 2019. Permeability of Epithelial/Endothelial Barriers in Transwells and Microfluidic Bilayer Devices. Micromachines (Basel). 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacco F, Brownlee M, 2010. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 107, 1058–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin-Dubourg A, et al. , 2012. Structural modifications of human albumin in diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 38, 171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BT, et al. , 2007. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability and altered tight junctions in experimental diabetes in the rat: contribution of hyperglycaemia and matrix metalloproteinases. Diabetologia. 50, 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber JD, 2008. Diabetes, cognitive function, and the blood-brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 14, 1594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, et al. , 2002. Synergistic effect of cold mannitol and Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchange blocker on blood-brain barrier opening. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 291, 669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariman K, et al. , 1986. Uncoupling effects of 2,4-dinitrophenol on electron transfer reactions and cell bioenergetics in rat brain in situ. Brain Res. 366, 300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura T, et al. , 2012. Cognitive impairment in diabetic patients: Can diabetic control prevent cognitive decline? J Diabetes Investig. 3, 413–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavulu MM, et al. , 2000. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme levels in type 2 diabetics with microvascular complications. Diabetes Metab. 26, 387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge MA, et al. , 2013. Mitochondria and endothelial function. Circ Res. 112, 1171–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S, et al. , 2012. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. J Physiol. 590, 3349–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, et al. , 2004. Hydrogen peroxide-induced alterations of tight junction proteins in bovine brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 68, 231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. , 2013. Green tea polyphenols alleviate early BBB damage during experimental focal cerebral ischemia through regulating tight junctions and PKCalpha signaling. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 13, 187–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liu X, et al. , 2017. The role of actin depolymerizing factor in advanced glycation endproducts-induced impairment in mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 433, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luévano-Contreras C, et al. , 2017. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products and Cardiometabolic Risk. Curr Diab Rep. 17, 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luissint AC, et al. , 2012. Tight junctions at the blood brain barrier: physiological architecture and disease-associated dysregulation. Fluids Barriers CNS. 9, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiya Y, et al. , 2012. Advanced Glycation End Products Increase Permeability of Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells through Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 21, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldendorf WH, et al. , 1977. The large apparent work capability of the blood-brain barrier: a study of the mitochondrial content of capillary endothelial cells in brain and other tissues of the rat. Ann Neurol. 1, 409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke J, et al. , 2013. Impaired mitochondrial energy production and ABC transporter function-A crucial interconnection in dementing proteopathies of the brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 134, 506–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradela-Dobarro B, et al. , 2016. Key structural and functional differences between early and advanced glycation products. J Mol Endocrinol. 56, 23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YY, et al. , 2014. MARCH5-mediated quality control on acetylated Mfn1 facilitates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell survival. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patche J, et al. , 2017. Diabetes-induced hepatic oxidative stress: a new pathogenic role for glycated albumin. Free Radic Biol Med. 102, 133–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters TJ, 1996. All about albumin - Biiochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications. Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, et al. , 2014. Diabetes Mellitus and Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction: An Overview. Journal of pharmacovigilance. 2, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasain N, Stevens T, 2009. The actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvascular research. 77, 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugazhenthi S, et al. , 2017. Common neurodegenerative pathways in obesity, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1863, 1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI, 2000. Osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier: principles, mechanism, and therapeutic applications. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 20, 217–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, et al. , 2017. Advanced glycation end-products decreases expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase through oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 16, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau P, Bourdon E, 2011. The glycation of albumin: structural and functional impacts. Biochimie. 93, 645–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saedi E, et al. , 2016. Diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairments. World Journal of Diabetes. 7, 412–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangle GV, et al. , 2010. Impairment of mitochondrial respiratory chain activity in aortic endothelial cells induced by glycated low-density lipoprotein. Free Radic Biol Med. 48, 781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghrouchni I, et al. , 2002. Oxidative stress parameters in type I, type II and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus; insulin treatment efficiency. Clin Chim Acta. 321, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahriyary L, et al. , 2018. Effect of glycated insulin on the blood-brain barrier permeability: An in vitro study. Arch Biochem Biophys. 647, 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu F, et al. , 2013. Advanced glycation end-products disrupt the blood-brain barrier by stimulating the release of transforming growth factor-beta by pericytes and vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinase-2 by endothelial cells in vitro. Neurobiology of Aging. 34, 1902–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P, et al. , 2005. Protein kinase D mediates mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling and detoxification from mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Molecular and cellular biology. 25, 8520–8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram RK, et al. , 1996. Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in type II diabetes mellitus with and without complications. Clin Sci (Lond). 90, 255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, et al. , 2014. Mitochondria, endothelial cell function, and vascular diseases. Front Physiol. 5, 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkat P, et al. , 2017. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption, Vascular Impairment, and Ischemia/Reperfusion Damage in Diabetic Stroke. Journal of the American Heart Association. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, et al. , 2013. Paracellular barrier and tight junction protein expression in the immortalized brain endothelial cell lines bEND.3, bEND.5 and mouse brain endothelial cell 4. Biol Pharm Bull. 36, 492–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wautier MP, et al. , 2014. [Advanced glycation end products: A risk factor for human health]. Ann Pharm Fr. 72, 400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtala A, et al. , 2014. Methods to monitor ROS production by fluorescence microscopy and fluorometry. Methods Enzymol. 542, 243–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PK, et al. , 2005. Endothelial F-actin cytoskeleton in the retinal vasculature of normal and diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 30, 279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.