Abstract

Fermatean fuzzy set, a generalization of the fuzzy set, is a significant way to tackle the complex uncertain information that arises in decision-analysis procedure and thus can be employed on a wider range of applications. Due to the inadequacy in accessible data, it is hard for decision experts to exactly define the belongingness grade (BG) and non-belongingness grade (NG) by crisp values. In such a situation, interval BG and interval NG are good selections. Thus, the aim of the study is to develop the doctrine of interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy sets (IVFFSs) and their fundamental operations. Next, the score and accuracy functions are proposed for interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy numbers (IVFFNs). Two aggregation operators (AOs) are developed for aggregating the IVFFSs information and discussed some axioms. Further, a weighted aggregated sum product assessment method for IVFFSs using developed AOs is introduced to handle the uncertain multi-criteria decision analysis problems. A case study of e-waste recycling partner selection is also considered to elucidate the feasibility and efficacy of the introduced framework. Finally, sensitivity and comparative analyses are given to elucidate the reliability and robustness of the obtained results.

Keywords: Interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy sets, Fermatean fuzzy sets, Aggregation operators, Multi-criteria decision analysis, WASPAS

Introduction

“Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)” is the fastest developing research field that offers the most ideal possible alternative from a set of finite options over certain attributes. In most of the realistic MCDA issues, we are unable to give accurate evaluation information of the candidate options because of the indeterminacy of “Decision Experts (DEs),” time limitations and lack of data. To conquer this disadvantage, [40] coined the notion of “Fuzzy Sets (FSs)” as an extension of conventional sets. Further, the doctrine of “Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (IFSs)” was initiated by [3] and exposed by the “Belongingness Grade (BG)”and the “Non-belongingness Grade (NG)” and fulfils a condition that the sum of BG and NG is less than or equal to one. Considering the unique advantages of IFSs, it has been obtained as one of the appropriate tools for describing the uncertainty and ambiguity of realistic problems [12, 29, 42]. In numerous claims, there may be a situation in which the DEs present their opinion in the form of BG and NG as (,). Accordingly, IFS is incapable of tackling this condition because To cope with the concern, [39] established the doctrine of “Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PFSs)” which are defined by the BG and NG, and satisfies a constraint that the squares sum of BG and NG is less than or equal to one. Therefore, it is considered as a more reliable and suitable tool to solve the complex MCDA problems. For instance, [18] investigated a number of aggregation operators on generalized PFSs to develop a MCDA procedure. [13] recommended an innovative decision support system for solving hierarchical MCDA problems with Pythagorean fuzzy information. Recently, [38] presented an “Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)” methodology to assess the sustainable supply chain innovation enablers on PFSs. In a study, [8] introduced a “Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL)” method on PFSs for software-defined network information security risk assessment. Later, [7] introduced a hybrid framework by combining “Stepwise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA)” and “Combined Compromise Solution (CoCoSo)” models with PFSs and further evaluated for the barriers of IoT implementation. Corresponding to the T-norm and S-norm, [1] proposed a method for calculating Pythagorean fuzzy similarity degree and their implementation in the decision analysis problem.

Further, [35] pioneered a broader version of these sets known as “q-Rung Orthopair Fuzzy Sets (q-ROFSs)” in which the sum of the qth power of the BG and NG is ≤ 1. According to [35], as q increases, the dimension of acceptable orthopair increases, and therefore, the more orthopair hold the bounding condition. In 2019, [36] presented the q-ROFSs as “Fermatean Fuzzy Sets (FFSs)” when . The FFSs are represented by the BG and NG such that their cube sum is less than or equal to unity. A vital difference among IFSs, PFSs and FFSs is the constraining relationship between the BG and NG. Thus, the FFSs are more powerful and operative tool than IFSs and PFSs for handling with uncertain MCDA problems. In the recent past, several scholars have focused their attention on the FFSs and applied for various purposes. Next, [36] gave a “Weighted Product Measure (WPM)” decision analysis model on FFSs. [5] presented the Dombi “Aggregation Operators (AOs)” for FFSs to handle the MCDA problems. [2] introduced some AOs using Einstein t-norm and t-conorm operations on FFSs. [16] gave some AOs on FFSs and used them to COVID-19 facility assessment. [19] initiated a “Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS)” model on FFSs to solve the green supplier evaluation problem. Based on Hamacher norm operations, [33] developed some Fermatean fuzzy Hamacher interactive geometric operators. In a study, [24] studied a new Fermatean fuzzy Einstein AOs-based MCDM model for the evaluation and prioritization of electric vehicle charging station locations. In accordance with the three-phase Fermatean fuzzy group decision analysis approach, [34] formulated the tax collection issue of governments to finance a public transportation system under the FFS context. Inspired by the Hamacher operational laws, [11] defined some Hamacher AOs under the FFS context and further utilized them to introduce a novel MCDM framework for cyclone disaster assessment. [10] introduced an innovative Fermatean fuzzy MCDA technique by combining the Dempster–Shafer theory and Fermatean fuzzy entropy.

While dealing with many practical decision problems under FFSs settings, it is very challenging for the DEs to precisely enumerate their decisions with crisp values because of inadequacy in available information. In such circumstances, it is worthwhile for DEs to deliver their decisions by an interval number within [0, 1]. However, some existing works have concentrated on the development of FFSs but ignore the extended information of FFSs. Thus, it is very essential to develop the notion of “Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Sets (IVFFSs),” which certify the BG and NG to assume interval values. This type of environment is more or less like that handled in IFSs such that the doctrine of IFSs has been generalized to the “Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (IVIFSs)” [4] to designate that interval values of BG and NG of an object are given to a set.

Motivated by the notion of FFSs, firstly we introduce the idea of IVFFSs and then develop two AOs: weighted averaging and geometric operators with their properties to aggregate the IVFF information. Further, the WASPAS framework is developed to solve the MCDA problems with the IVFFSs setting. The key outcomes of the paper are as follows:

To introduce the notion of IVFFS and its fundamental operations.

To propose two AOs namely “Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Weighted Averaging Operator (IVFFAO),” “Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Weighted Geometric Operator (IVFFGO)” and verify their properties.

Corresponding to the proposed AOs, we introduce a novel WASPAS framework for dealing MCDA problems with IVFFSs.

To elucidate the applicability and powerfulness of the developed method, a multi-criteria e-waste recycling partner selection problem is discussed.

The rest of the article is arranged as Sect. 2 offers the basic notions related to FFSs. Section 3 defines the concept, several operations, score and accuracy functions of IVFFSs. Section 4 presents different aggregation operators with their properties. Section 5 introduces a novel WASPAS method under IVFFSs settings. Section 6 presents an illustrative example of e-waste recycling partner selection, which reveals the practicality of the introduced approach. Section 7 concludes the whole paper and delivers future scope.

Prerequisites

Here, we present some fundamental ideas related to FFSs.

Definition 2.1

[36]. A FFS F on fixed set U is defined as where denote the BG and NG of an element to F, respectively, with a condition The indeterminacy degree is given by Next, [36] named as a “Fermatean Fuzzy Number (FFN)” and is described by where and

Definition 2.2

For an FFN , [36, 37] defined the concept of score and accuracy functions and defined by.

and

wherein and

Definition 2.3

For three FFNs and the fundamental operations on FFNs are defined by [36, 37]

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

-

(v)

-

(vi)

-

(vii)

Interval-valued fermatean fuzzy sets (IVFFSs)

This section develops the idea of IVFFSs and their fundamental properties, which are the basis of this study.

Definition 3.1

Let signifies the set of all closed subintervals of and U be a fixed set. Then an IVFFS in U is defined by

| 1 |

where and Here, and represent the BG and NG of correspondingly, in terms of interval values. The function denotes the indeterminacy degreeof to where and For simplicity, an “Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Number (IVFFN)” is signified by which fulfils For convenience, the pair is symbolized by

There are some special cases of IVFFS, given as (a) if and for all then an IVFFS reduces to an FFS proposed by [36, 37] if then IVFFS transforms to IVIFS, and (c) if then IVFFS reduces to interval-valued PFS (IVPFS).

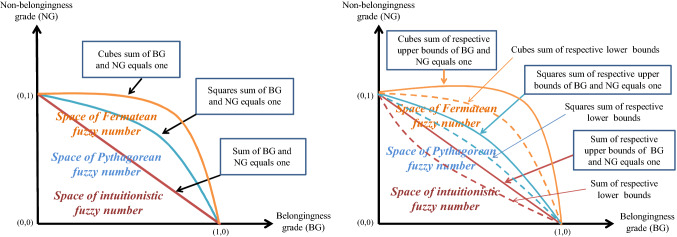

Here, this paper would like to take the powerfulness of the theory of Fermatean fuzziness into account to portray uncertainty, imprecision, and vagueness in a more flexible manner. The FFSs, which were initiated by [36], are characterized by BG and NG, whose cubes sum is less than or equal to one but the sum is not required to be less than one [11, 31, 36]. It is worth mentioning that the prime difference between FFSs, IFSs and PFSs is their distinct constraints. Figure 1(a) validates the comparison of spaces of FFNs, PFNs and IFNs. It is clear that the space of an FFN is larger than the space of PFN and IFN. Thus, FFSs can not only depict uncertain information, which PFSs and IFSs can capture but also model more imprecise and uncertain information, which the latter cannot define [19, 37].

Fig. 1.

Geometrical interpretations of IF/IVIF/, PF/IVPF and FF/IVFF numbers. (i) Comparison of spaces of IF, PF and FFNs. (ii) Comparison of spaces of IVIF, IVPF and IVFF numbers

The concept of IVFFSs is an extension of FFSs. IVFFSs is three-dimensional and their BG, NG and hesitation grade are represented by an interval within [0, 1]. In the meantime, the only constraint is that the cube sum of respective upper bounds of the interval-valued BG and interval-valued NG is ≤ 1. Figure 1(b) illustrates the comparison of spaces of “Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers (IVIFNs)” and “Interval-Valued Pythagorean Fuzzy Numbers (IVPFNs).” Equivalently, the space of IVFFNs is greater than the space of IVPFNs and IVIFNs. Due to the relaxed constraint, IVFFSs are more accurate for handling complex uncertain MCDA problems compared with IVPFSs and IVIFSs. More significantly, the BG and NG within an IVFFN are signified by flexible interval values. Thus, comparing with the FFSs, IVFFSs can describe the hesitation grade more precisely. Consider that the DE’s subjective decision is often vague under various situations. Furthermore, the available information is often inadequate for the DEs or researchers to obtain exact BG and NG for certain assessment objects. From this viewpoint, IVFFSs with flexible interval-valued BG/NG are suitable for addressing such concerns.

Motivated by the concept of FFSs, IVPFSs and IVIFSs, the following definitions are presented for IVFFSs:

Definition 3.2

Let and be two IVFFNs. Then, the relations between them are defined as follows:

-

(i)

iff and

-

(ii)

iff and

Definition 3.3

For any IVFFN the score function is given by

| 2 |

Clearly, by definition, the larger the score function the greater the In particular, if then is the largest IVFFN and if then is the largest IVFFN

However, if we take and then Here, the score values cannot differentiate the IVFFNs and Thus, we define the following definition:

Definition 3.4

For any IVFFN the accuracy function of is given by

| 3 |

Corresponding to the score and accuracy functions, a comparative scheme is presented to compare any two IVFFNs and given as

-

(i)

If then

-

(ii)

If then

-

(iii)

If then

-

(iv)

If then

-

(v)

If then

Definition 3.5

Let and be three IVFFNs and Then, the operations on IVFFNs are given by

Remark 3.1

Here, let us discuss at and for some particular cases of and :

Theorem 3.1

Let and be three IVFFNs and Then, the following properties are valid:

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

-

(v)

-

(vi)

-

(vii)

-

(viii)

-

(ix)

-

(x)

-

(xi)

-

(xii)

-

(xiii)

-

(xiv)

-

(xv)

Proof

It is trivial by Definition 3.5.

Theorem 3.2

Let and be two IVFFNs. Then

-

(i)

-

(ii)

Proof

-

(i)

-

(ii)

In a similar way, we can prove this part.

Theorem 3.3

Let and be three IVFFNs. Then,

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

-

(v)

-

(vi)

Proof

(i)

Similarly, we can prove (ii)-(vi).

Theorem 3.4

Let and be three IVFFNs. Then,

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

Proof

As it is trivial by definition, therefore we have omitted these proofs.

Aggregation operators on IVFFNs

Here, we develop the notions of the averaging operator and geometric operator on IVFFNs with several elegant properties.

Interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy weighted averaging operator (IVFFWAO)

Definition 4.1

Consider () be a collection of IVFFNs and then the IVFFWAOs can be given by

| 4 |

where is a set of all IVFFNs and is weight value with and

According to Definition 3.5, we develop the succeeding theorem:

Theorem 4.1

Let () be a collection of IVFFNs. Then, the aggregated value by IVFFWAO is an IVFFN and

| 5 |

Proof

To prove Eq. (5), we utilize mathematical induction on positive integer n. When we get

Thus, Eq. (5) satisfies for

Suppose that Eq. (5) is valid for i.e.,

Then, when by inductive assumption and Definition 3.5, we obtain

Therefore, for theorem is true. Hence, Eq. (5) is valid for all

In what follows, we demonstrate the aggregation outcome by the IVFFWAO is also an IVFFN.

Since being the collection of IVFFNs, we have and Thus, we have the following results:

In a similar way, we obtain the inequalities as

Since and we identify that two inequalities hold as follows:

So, we have

Since and therefore, it is simply to show that the given inequality fulfils:

As we know by definition that so we can derive the following results:

Further, we have

Thus, the aggregation outcome by IVFFWAO fulfils Definition 4.1, which shows that the aggregation outcome by IVFFWAO is also an IVFFN.

In particular, if then IVFFWAO converts into the IVFF averaging (IVFFA) operator:

| 6 |

Corresponding to Theorem 4.1, we deduce the subsequent properties:

Property 4.1 (Idempotency)

If all are equal and for all then

Proof

Property 4.2 (Monotonicity)

Consider two collections and () such that and then

Proof

Let and Since and for all then we have

Similarly, we have

Corresponding to Definition 3.3, we get Also, we deliberate the following two cases:

-

(i)

If then by the comparative scheme, we know that holds.

-

(ii)If then according to Definition 3.3, we obtain

With the following conditions and for all we get

,

which signifies that the degrees of accuracy functions and are same. It implies Thus, by Eqs. (1) and (2), we will get

Property 4.3 (Boundedness)

Let () be the IVFFNs, then

where and

Proof

Let

and

Consider that

Then obviously

| 7 |

| 8 |

Thus, from Eqs. (7) and (8), we have

Interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy weighted geometric operator (IVFFWGO)

Definition 4.2

Let () be a collection of IVFFNs and then the IVFFWGOs can be given by

| 9 |

Corresponding to Definition 3.5, we discuss the theorem as.

Theorem 4.2

Let () be the IVFFNs. Then the aggregated value with the IVFFWGO is still an IVFFN and

| 10 |

Proof

With the use of Definition 3.5, we can prove this theorem as similar to Theorem 4.1.

Specifically, if then the IVFFWGO reduces to the following IVFF geometric (IVFFG) operator:

| 11 |

Based on Theorem 4.2, we deduce the given axioms:

Property 4.4 (Idempotency)

If all are equal and for all then

Property 4.5 (Monotonicity)

Consider two collections and () such that and then

Property 4.6 (Boundedness)

Let be the IVFFNs, then.

where and

Proposed IVFF-WASPAS framework for MCDM problems

The WASPAS framework [41] is an inventive utility measure-based model that has been extensively used in copious realistic settings. It combines the WSM and WPM. Thus, it is more exact than these two models. Recently, [22] extended WASPAS framework to assess the management policy of reservoir flood control on IVIFSs. [25] assessed the work of safety advisors for transporting hazardous materials by employing a linguistic neutrosophic WASPAS model. [17] gave WASPAS model to assess industrial robot assessment problems. [30] gave an information measures-based WASPAS model on PFSs to solve the physician assessment problem. [21] suggested a hybrid MCDA system by integrating SWARA and WASPAS methods with HFSs and further applied it for evaluating the main challenges of digital health interventions adoption during the COVID-19 disease. Apart from these studies, several other articles have been extended the WASPAS approach under different environments [9, 20, 23, 26]. After analyzing the literature, it has been concluded that formerly developed WASPAS methods are unable to deal with multi-criteria decision making problems with interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy information. To overcome this drawback, the present work introduces a new WASPAS method for the assessment of alternatives from interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy perspective. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel IVFF-WASPAS method developed for selecting most appropriate e-waste recycling partner alternative from sustainable perspective, which makes an attempt to extent the application domains of WASPAS approach.

In this section, the WASPAS framework is developed to assess the MCDA problems with IVFFSs. The assessment process of the introduced method is designated as:

Step 1: Generate the decision-matrix.

In the MCDA structure, the goal is to select the optimal option from a set of options with respect to attribute/criterion set where the features of each option are specified in the term of IVFFNs where gives the BG of option in terms of favors, while provides the NG of option in terms of against for ith option over jth attribute. Thus, an IVFF-Decision-Matrix (IVFF-DM), can be formulated as

| 12 |

Step 2: Form the normalized IVFF-DM (NIVFF-DM).

The NIVFF-DM is evaluated from and defined by

| 13 |

Step 3: Corresponding to the score values, the NIVFF-DM is converted into the score matrix and is given by

| 14 |

where are calculated by utilizing Definition 3.3.

Since it is observed that the priority outcome of options is highly associated with criteria weights, the exact assessment of criteria weights plays a prominent role in the MCDA procedure. Consequently, in the MCDA process, a suitability function (SF) is constructed by multiplying the score value of each attribute with their weight as

| 15 |

Step 4: Construct a linear model to compute attribute weights.

In this formula, the term signifies the weight of attribute and the partly known weight subset is given by The function is applied to find the SF to which an alternative fulfils the DEs’ settings. Furthermore, an accurate weight value should generate the whole assessment of each option as large as possible. This concept shows the preparation of linear programming method for evaluating the weight as follows:

| 16 |

Here, signifies the overall score value for each option After simplifying the model (M-I), we get the weight vector

Step 5: Evaluate the “Weighted Sum Model (WSM)” measure for each option as follows:

| 17 |

Step 6: Estimate the “Weighted Product Model (WPM)” measure for each option as follows:

| 18 |

Step 7: Assess the combined or WASPAS measure for each alternative by the formula

| 19 |

where implies the coefficient of decision-procedure, such that (when and WASPAS is transformed into the WPM and WSM, respectively).

Case study: E-waste recycling partner (WRP) selection

Over the past years, the huge amount of wastes produced and has posed a constantly growing risk to the environment and public health. E-waste or “Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE)” has been one of the emerging waste streams in the globe. Basically, e-waste is a slack type of spare, obsolete, broken, or discarded WEEEs. During these years, the utilization and dependency on electrical and electronic gadgets namely mobile phones, computers, laptops, televisions, refrigerators, air conditioners, and others have been increasing and causing the generation of a huge amount of WEEE. However, e-waste comprises precious materials namely aluminum, copper, gold, palladium, silver, and also comprises injurious elements namely cadmium, lead and mercury. In the lack of appropriate awareness, disposing of e-waste in landfills can affect toxic emissions to the air, water and soil and pose severe health and environmental impacts. The world generates 50 million tons per annum (TPA) of e-waste, based on the latest United Nations report, but only 20% is properly recycled. Copious of the remaining finishes up in landfill or is reprocessed casually in emerging countries. Unempirical disposal of e-waste points to the loss of existing valuable materials and laid more stress on the ever-depleting natural resources (NRs). Thus, there is a need to reassure recycling of all advantageous and valuable metals from e-waste, so as to preserve the ever-depleting NRs.

India is one of the leading waste generating nations in the globe [6]. India continuously produces huge amounts of e-waste after the China, USA, Japan and Germany. According to the report, India produces more than two million TPA of e-waste, out of which merely 4.3 lakhs TPA is recycled. Approximately 90% of the e-waste that has been produced in the nation end up in the muddled market for recycling and disposal. The disorganized region primarily involves the urban slums of the metros and mini-metros where recycling procedures are implemented by the inexperienced workers by the ultimate elementary systems to decrease cost. Thus, the e-waste (Management & Handling) guidelines, 2011, have been advised with the key objective to channelize the e-waste produced in the nation for ecologically sound recycling which is mainly handled by the disorganized regions who are implementing crude performs that consequence into greater pollution and a smaller amount of recovery, thereby affecting wastage of valuable assets and harm to the environment. The proper management of e-waste in India is needed to make an effort to move e-waste into publically and modernly valuable crude materials namely profitable metals, plastics and glasses, natural benevolent inventions suitable to Indian settings.

In order to validate the applicability of the IVFF-WASPAS approach, we discuss a case study of e-waste recycling partner assessment of an electronics firm (ABC) located in Delhi, India, adopted from [7]. In this work, we have focused on the utilization of an innovative method that will assist the firm’s stakeholders to evaluate and opt for the most suitable option. Firstly, a group of decision-makers is formed to evaluate this decision-making process. After the primary screening, we have chosen four recycling partners, who are involved in the recycling procedures of WEEEs, and form a set of WRP options X = {X1, X2, X3, X4}. These four alternatives will be evaluated under the following four attributes: Recycling performance and delivery history (V1), Environmental management system (V2), Reduction in GHG emission (V3) and Recycling cost (V4). In this study, the attributes V1, V2 and V3 are of benefit criteria and V4 is of cost criterion. The procedural steps of the developed framework are given by.

Step 1: Assume that the options are evaluated over each criterion and their assessment degrees are given by the group of DEs in terms of IVFFNs, which is represented by and is portrayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

IVFF-DM for e-waste recycling partner assessment

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | ([0.45,0.65], [0.55,0.75]) | ([0.60, 0.75], [0.35,0.50]) | ([0.65,0.75], [0.40,0.55]) | ([0.40,0.55], [0.65,0.80]) |

| X2 | ([0.65,0.70], [0.40,0.65]) | ([0.50, 0.60], [0.65,0.75]) | ([0.60,0.65], [0.50,0.60]) | ([0.55,0.65], [0.55,0.70]) |

| X3 | ([0.70,0.80], [0.40,0.60]) | ([0.70, 0.75], [0.30,0.45]) | ([0.55,0.65], [0.45,0.55]) | ([0.50,0.60], [0.60,0.65]) |

| X4 | ([0.68,0.75], [0.45,0.55]) | ([0.65, 0.70], [0.45,0.60]) | ([0.57,0.65], [0.40,0.55]) | ([0.50,0.55], [0.50,0.70]) |

In this matrix, the IVFFN ([0.45,0.65], [0.55,0.75]) corresponding to X1 and V1 signifies that the degrees to which option X1 satisfies an attribute V1 belongs to the interval [0.45,0.65] and dissatisfies V1 lies in [0.55,0.75], respectively. The remaining IVFFNs of the given matrix have a similar meaning. Also, the significance of attributes set (partly known criteria weight information) is different, presented by decision expert is [0.20, 0.30], [0.15, 0.25], [0.18, 0.28] and [0.25, 0.35] to choose the appropriate recycling partner alternative.

Step 2: Since the criteria V4 is cost criterion and the rest of the benefit criteria, thus, the NIVFF-DM is computed and mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

NIVFF-DM for e-waste recycling partner assessment

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | ([0.45,0.65], [0.55,0.75]) | ([0.60, 0.75], [0.35,0.50]) | ([0.65,0.75], [0.40,0.55]) | ([0.65,0.80], [0.40,0.55]) |

| X2 | ([0.65,0.70], [0.40,0.65]) | ([0.50, 0.60], [0.65,0.75]) | ([0.60,0.65], [0.50,0.60]) | ([0.65,0.70], [0.55,0.65]) |

| X3 | ([0.70,0.80], [0.40,0.60]) | ([0.70, 0.75], [0.30,0.45]) | ([0.55,0.65], [0.45,0.55]) | ([0.60,0.65], [0.50,0.60]) |

| X4 | ([0.68,0.75], [0.45,0.55]) | ([0.65, 0.70], [0.45,0.60]) | ([0.57,0.65], [0.40,0.55]) | ([0.50,0.70], [0.50,0.55]) |

Step 3: Applying Definition 3.3, we create the collective score matrix from normalized IVFF-DM and discussed it in Table 3.

Table 3.

Collective score function matrix for e-waste recycling partner assessment

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | − 0.1113 | 0.2350 | 0.2331 | 0.2781 |

| X2 | 0.1395 | − 0.1778 | 0.0748 | 0.0883 |

| X3 | 0.2875 | 0.3234 | 0.0917 | 0.0748 |

| X4 | 0.2394 | 0.1552 | 0.1147 | 0.0883 |

Step 4: Assume the attribute weights’ value, which is partly known and is specified as

| 20 |

According to this information, a linear programming model is constructed by

| 21 |

and therefore the attribute weights are calculated as

Steps 5–7: Using (17)-(19), the WSM WPM and WASPAS measures for each alternative and their relative scores and are calculated and mentioned in Table 4. Hence, the priority order of e-waste recycling partner alternatives is found as and thus, X3 is the most desirable alternative.

Table 4.

Degree of WASPAS measure for e-waste recycling partner assessment

| Options | IVFF-WSM | IVFF-WPM | IVFF-WASPAS | Ranking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | ([0.593, 0.742], [0.426,0.589]) | 0.1678 | ([0.571, 0.731], [0.450,0.625]) | 0.1208 | 0.1443 | 3 |

| X2 | ([0.612, 0.670], [0.512,0.664]) | 0.0514 | ([0.600, 0.665], [0.542,0.673]) | 0.0228 | 0.0371 | 4 |

| X3 | ([0.655, 0.732], [0.404,0.550]) | 0.2201 | ([0.643, 0.717], [0.425,0.562]) | 0.1900 | 0.2051 | 1 |

| X4 | ([0.616, 0.709], [0.453,0.562]) | 0.1598 | ([0.599, 0.705], [0.457,0.564]) | 0.1457 | 0.1527 | 2 |

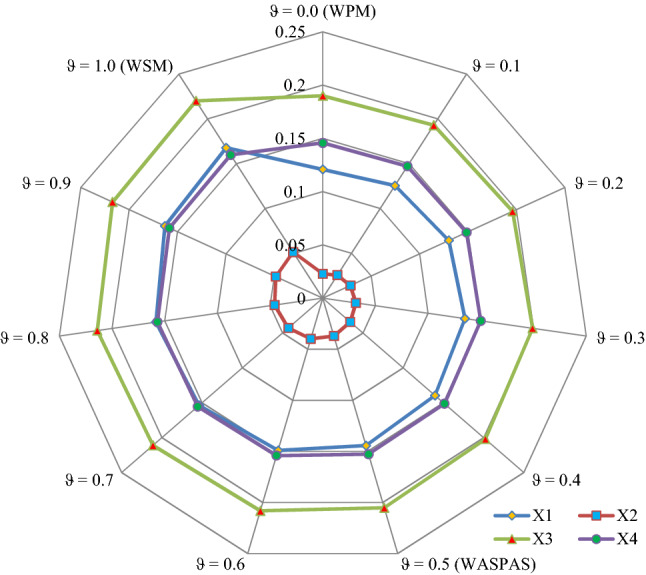

Sensitivity assessment

We execute a sensitivity assessment over the various values of the parameter (ϑ). In what follows, we continuously examine the effects of the parameters on the e-waste recycling partner selection. Various values are considered for investigation. This assessment is deliberated to express the performance of the introduced framework. Varying the parameter can assist the DEs to evaluate the sensitivity of the introduced model from WSM to WPM. The sensitivity analysis outcomes in Table 5 and Fig. 2 show that the best alternative X3 is the same in each parameter value, while the priority order of alternatives is different over different parameter values. From Table 5 and Fig. 2, the preference order of the options is when ϑ = 0.0 to 0.7 and while ranking order is when ϑ = 0.8 to 1.0. Hence, it is concluded that the assessment of e-waste recycling partners is reliant on and sensitive to ϑ values. Henceforth, the introduced model has ample stability over different parameters values. According to Fig. 2, for all ϑ, an alternative has the first rank. In accordance with the aforesaid view, it is witnessed that the variation of parameter degrees will enhance the permanence of the proposed framework.

Table 5.

WASPAS measure of e-waste recycling partner assessment with diverse parameter values

| ϑ = 0.0 | ϑ = 0.1 | ϑ = 0.2 | ϑ = 0.3 | ϑ = 0.4 | ϑ = 0.5 | ϑ = 0.6 | ϑ = 0.7 | ϑ = 0.8 | ϑ = 0.9 | ϑ = 1.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.1208 | 0.1255 | 0.1302 | 0.1349 | 0.1396 | 0.1443 | 0.1490 | 0.1537 | 0.1584 | 0.1631 | 0.1678 |

| X2 | 0.0228 | 0.0256 | 0.0285 | 0.0314 | 0.0342 | 0.0371 | 0.0399 | 0.0428 | 0.0457 | 0.0485 | 0.0514 |

| X3 | 0.1900 | 0.1930 | 0.1960 | 0.1991 | 0.2021 | 0.2051 | 0.2081 | 0.2111 | 0.2141 | 0.2171 | 0.2201 |

| X4 | 0.1457 | 0.1471 | 0.1485 | 0.1499 | 0.1513 | 0.1527 | 0.1541 | 0.1555 | 0.1570 | 0.1584 | 0.1598 |

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity assessments of WASPAS measure values over decision coefficient parameter (ϑ)

Comparison with extant methods

In the current section, we compare the developed approach with the extant methods as presented by various researchers [27, 14, 15, 28] for assessing the best options. Their corresponding outcomes are depicted in Table 6. From Table 6, the behavior of the relative score degrees or closeness index follows the same style (increasing or decreasing). Thus, the introduced method is consistently elucidated the MCDA concerns on FFSs and IVFFSs settings.

Table 6.

Comparative discussion

| Methods | Score values | Order of option | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | ||

| Peng and Yang (2016): IVPFWA | 0.1838 | 0.0583 | 0.2468 | 0.1783 | |

| Peng and Yang (2016): IVPFWG | 0.1404 | 0.0317 | 0.1924 | 0.1461 | |

| Garg (2017): IVPF-TOPSIS method | 0.0802 | 0.0242 | 0.3109 | 0.1040 | |

| Garg (2018): Improved score function | 0.2436 | 0.0625 | 0.3383 | 0.2606 | |

| Peng and Li (2019): IVPF-WDBA | 0.1424 | 0.0347 | 0.2038 | 0.1551 | |

| Proposed: IVFF-WSM | 0.1678 | 0.0514 | 0.2201 | 0.1598 | |

| Proposed: IVFF-WPM | 0.1208 | 0.0228 | 0.1900 | 0.1457 | |

| Proposed: IVFF-WASPAS | 0.1443 | 0.0371 | 0.2051 | 0.1527 | |

Figure 3 displays the score values or closeness indices, compared with the extant MCDA methods. Numerous fascinating patterns are obtained in these outcomes that are taken by the comparisons. These methods are compared to each other and identified the alternative X3 to be the best option, as depicted in Fig. 3. Here, the number of alternatives is limited to the four; the outcome of the introduced approach might not be observed as conclusive. Now, the number of options increase, the outcome will become much more apparent. Therefore, it is concluded from the assessment that the remaining priority order is different for options, signifying a pure benefit by its operative and proficient computation process, as reasonable in previous sections.

Fig. 3.

Alternative rankings for different MCDM methodologies

Moreover, we discuss some experiments study to reinforce our claim of developing an improved framework for IVFF-based MCDA concerns.

In [15] and [28], the alternatives are ranked using the relative closeness coefficient and suitability index, respectively, between the overall value of the alternatives and the ideal alternative. This is not sufficient to conclude how good or bad an alternative is. In the IVFF-WASPAS method, the benefit and the cost criteria are both considered with proposed AOs on IVFFSs which comprise a more precise outcome compared with simply dealing with benefit or cost criteria. In the meantime, it increases the practicality of assessment data and the precision of outcomes as well.

The main benefit of the introduced IVFF-WASPAS model is capable of assessing any MCDA issues with uncertainty through IVFFNs as well as IFNs, PFNs, FFNs, IVIFNs and IVPFNs [14, 15] as described in the previous sections.

The proposed IVFF-WASPAS framework, which is utility or scoring degree-based model for MCDA, selects an option with the highest utility degree; therefore, the concern is how to assess the prior multi-criteria utility degree for an appropriate decision setting, whereas the extant models, which are compromise degree models, select an option which is nearest to the ideal solution.

The proposed IVFF-WASPAS is one of the robust and novel MCDA utility measuring methods. This framework is a combination of IVFF-WPM and IVFF-WSM. The accuracy of IVFF-WASPAS is strengthening than WPM and WSM. The proposed method enables to reach the highest accuracy of assessment for utilizing the proposed approach for optimization of weighted AOs.

All the existing AOs utilize different operations on BGs and NGs information, it is necessary to propose some neutral AOs about them due to that we are neutral in several issues and need to be treated fairly. Here, we have implemented combined IVFF-WSM and IVFF-WPM aggregation operators to get more reasonable outcomes.

In [14], the discrimination is computed between the overall criterion degree of an option and the IVFF-IS and the IVFF-AIS to define the relative closeness index of each option on the given criteria. The IVFF-IS and IVFF-AIS may be considered as standards against which the performance of the options over the criteria is assessed. Mention that these standards are too impracticable to be accomplished in practice, whereas the IVFF-WASPAS approach assumes both concerns of attributes according to the utility degree evaluation, which holds more precise information compared with different extant models mostly considering the benefit or cost attribute. Therefore, the standards are found on IVFFWAO, IVFFWGO, and the proposed score function, which is more accurate in the sense that the expert knowledge not only about the IS and AIS performance of options over the criteria but also a relative comparison of the performances among them.

When the number of attributes and options becomes very large, the IVFF-WASPAS approach has more operability than the IVPF-TOPSIS [14] and IVPF-WDBA [28]. In IVFF-WASPAS approach, there is no need to obtain the IVFF-IS and IVFF-AIS. The results can be obtained with the processing of realistic data, which allows IVFF-WASPAS approach to applying more complex and realistic MCDA problems.

Conclusions

The goal of this study is to introduce the notion of “Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Sets (IVFFSs)” which permits the decision-making expert to provide the BGs and NGs of a set of options in terms of the interval; therefore, the range of uncertain information they can portray is wider. Corresponding to the FFSs and interval-valued fuzzy sets, we have discussed the fundamental operational laws, score and accuracy functions for IVFFNs. Based on the operations of IVFFSs, the IVFFWAO and IVFFWGO have been investigated with their elegant postulates including idempotency, monotonicity, and boundedness. Next, we have established an extended WASPAS-based methodology by means of the proposed operators to solve MCDA problems from an interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy perspective. Finally, to demonstrate the effectiveness and applicability of the developed model, a case study of e-waste recycling partner assessment has been presented on IVFFSs. In addition, sensitivity investigation has been done to check the robustness of the obtained result. At last, we have conducted a comparison between the developed and some of the extant models, which demonstrates its applicability and advantages.

In future, we will develop some more aggregation operators for IVFFSs. At the same time, we will apply these operators for the introduction of new MCDA models and try to investigate several applications including game theory, cluster analysis, medical diagnosis, image processing and MCDA problems.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pratibha Rani, Email: pratibha138@gmail.com.

Arunodaya Raj Mishra, Email: arunodayaraj.math@itmuniversity.ac.in.

References

- 1.Agheli B, Firozja MA, Garg H. Similarity measure for Pythagorean fuzzy sets and application on multiple criteria decision making. J Stat Manag Syst. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09720510.2021.1891699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akram M, Shahzadi G, Ahmadini AAH. Decision-making framework for an effective sanitizer to reduce COVID-19 under Fermatean fuzzy environment. J. Mathem. 2020;2020:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atanassov KT. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986;20:87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0114(86)80034-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atanassov KT, Gargov G. Interval valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1989;31(3):343–349. doi: 10.1016/0165-0114(89)90205-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aydemir SB, Gunduz SY. Fermatean fuzzy TOPSIS method with dombi aggregation operators and its application in multi-criteria decision making. J. Intell and Fuzzy Syst. 2020 doi: 10.3233/JIFS-191763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ASSOCHAM-cKinetic, India's E-Waste Growing at 30% Per Annum, 2016. Assocham India, New Delhi India, 2016. Available at. http://www.assocham.org/newsdetail.php?id=5725. (Accessed 2 December 2017)

- 7.Cui Y, Liu W, Rani P, Alrasheedi M. Internet of Things (IoT) adoption barriers for the circular economy using Pythagorean fuzzy SWARA-CoCoSo decision-making approach in the manufacturing sector. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deb R, Roy S. A software defined network information security risk assessment based on Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Expert Syst Appl. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorfeshan Y, Mousavi SM. A novel interval type-2 fuzzy decision model based on two new versions of relative preference relation-based MABAC and WASPAS methods (with an application in aircraft maintenance planning) Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32:3367–3385. doi: 10.1007/s00521-019-04184-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng Z, Wang J. Evidential Fermatean fuzzy multicriteria decision-making based on Fermatean fuzzy entropy. Int J Intell Syst. 2021 doi: 10.1002/int.22534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadi A, Khan W, Khan A. A novel approach to MADM problems using Fermatean fuzzy Hamacher aggregation operators. Int J Intell Syst. 2021;36:3464–3499. doi: 10.1002/int.22423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan J, Li X. Similarity of intuitionistic fuzzy sets and its applications. Int J Approx Reas. 2021;137:166–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijar.2021.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fei L, Deng Y. Multi-criteria decision making in Pythagorean fuzzy environment. Appl Intell. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10489-019-01532-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg H. A new improved score function of an interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy set based TOPSIS method. Int J Uncertain Quantif. 2017;7(5):463–474. doi: 10.1615/Int.J.UncertaintyQuantification.2017020197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg H. A linear programming method based on an improved score function for interval valued Pythagorean fuzzy numbers and its application to decision-making. Int. J. Uncertainty Fuzziness Knowledge-Based Syst. 2018;26(1):67–80. doi: 10.1142/S0218488518500046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg H, Shahzadi G, Akram M. Decision-making analysis based on Fermatean fuzzy yager aggregation operators with application in COVID-19 testing facility. Mathem Probl Eng. 2020;2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gundogdu FK, Kahraman C. Extension of WASPAS with spherical fuzzy Sets. Informatica. 2019;30(2):269–292. doi: 10.15388/Informatica.2019.206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi BP. Pythagorean fuzzy average aggregation operators based on generalized and group-generalized parameter with application in MCDM problems. Int J Intell Syst. 2019;34(5):895–919. doi: 10.1002/int.22080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keshavarz-Ghorabaee M, Amiri M, Hashemi-Tabatabaei M, Zavadskas EK, Kaklauskas A. A new decision-making approach based on Fermatean fuzzy sets and WASPAS for green construction supplier evaluation. Mathematics. 2020;8:01–24. doi: 10.3390/math8122202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishankumar R, Subrajaa LS, Ravichandran KS, Kar S, Saeid AB. A framework for multi-attribute group decision-making using double hierarchy hesitant fuzzy linguistic term set. Int J Fuzzy Syst. 2019;21:1130–1143. doi: 10.1007/s40815-019-00618-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mardani A, Saraji MK, Mishra AR, Rani P. A novel extended approach under hesitant fuzzy sets to design a framework for assessing the key challenges of digital health interventions adoption during the COVID-19 outbreak. Appl Soft Comput. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra AR, Rani P. Interval-valued Intuitionistic fuzzy WASPAS method: application in reservoir flood control management policy. Group Decis Negot. 2018;27:1047–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10726-018-9593-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra AR, Rani P, Pardasani KR, Mardani A. A novel hesitant fuzzy WASPAS method for assessment of green supplier problem based on exponential information measures. J Clean Prod. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra AR, Rani P. Multi-criteria healthcare waste disposal location selection based on Fermateanfuzzy WASPAS method. Complex & Intelligent Systems. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40747-021-00407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pamucar D, Sremac S, Stevic Z, Cirovic G, Tomic D. New multi-criteria LNN WASPAS model for evaluating the work of advisors in the transport of hazardous goods. Neural Comput Appl. 2019;31:5045–5068. doi: 10.1007/s00521-018-03997-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prajapati H, Kant R, Shankar R. Prioritizing the solutions of reverse logistics implementation to mitigate its barriers: a hybrid modified SWARA and WASPAS approach. J Clean Prod. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng X, Yang Y. Fundamental properties of interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy aggregation operators. Int J Intell Syst. 2016;31(5):444–487. doi: 10.1002/int.21790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng X, Li W. Algorithms for interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy sets in emergency decision making based on multi-parametric similarity measures and WDBA. IEEE Access. 2019 doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2890097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raji-Lawal HY, Akinwale AT, Folorunsho O, Mustapha AO. Decision support system for dementia patients using intuitionistic fuzzy similarity measure. Soft Comput Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.socl.2020.100005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rani P, Mishra AR, Pardasani KR. A novel WASPAS approach for multi criteria physician selection problem with intuitionistic fuzzy type-2 sets. Soft Comput. 2020;24:2355–2367. doi: 10.1007/s00500-019-04065-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rani P, Mishra AR. Novel single-valued neutrosophic combined compromise solution approach for sustainable waste electrical and electronics equipment recycling partner selection. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2020.3033121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rani P, Mishra AR. Fermatean fuzzy einstein aggregation operators-based MULTIMOORA method for electric vehicle charging station selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahzadi G, Zafar F, Alghamdi MA. Multiple-attribute decision-making using Fermatean fuzzy Hamacher interactive geometric operators. Mathem Probl Eng. 2020;2020:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2020/6737243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simic V, Gokasar I, Deveci M, Isik M. Fermatean fuzzy group decision-making based CODAS approach for taxation of public transit investments. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2021 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2021.3109038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yager RR. Generalized orthopair fuzzy sets. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2017;25:1222–1230. doi: 10.1109/TFUZZ.2016.2604005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senapati T, Yager RR. Fermatean fuzzy sets. J Amb Intell Human Comput. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12652-019-01377-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senapati T, Yager RR. Some new operations over Fermatean fuzzy numbers and application of Fermatean fuzzy WPM in multiple criteria decision making. Informatica. 2019;30(2):391–412. doi: 10.15388/Informatica.2019.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shete PC, Ansari ZN, Kant R. A Pythagorean fuzzy AHP approach and its application to evaluate the enablers of sustainable supply chain innovation. Sust Prod and Cons. 2020;23:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yager RR. Pythagorean membership grades in multicriteria decision making. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2014;22:958–965. doi: 10.1109/TFUZZ.2013.2278989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Inf Control. 1965;8(3):338–353. doi: 10.1016/S0019-9958(65)90241-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zavadskas EK, Turskis Z, Antucheviciene J, Zakarevicius A. Optimization of weighted aggregated sum product assessment. Electronics and Electrical Engineering. 2012;6:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou XY, Chen SM, Fan KY. Multiple attribute decision making using improved intuitionistic fuzzy weighted geometric operators of intuitionistic fuzzy values. Inf Sci. 2020;535:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2020.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]