Abstract

We report the first described case of Arthrographis kalrae pansinusitis and meningitis in a patient with AIDS. The patient was initially diagnosed with Arthrographis kalrae pansinusitis by endoscopic biopsy and culture. The patient was treated with itraconazole for approximately 5 months and then died secondary to Pneumocytis carinii pneumonia. Postmortem examination revealed invasive fungal sinusitis that involved the sphenoid sinus and that extended through the cribiform plate into the inferior surfaces of the bilateral frontal lobes. There was also an associated fungal meningitis and vasculitis with fungal thrombosis and multiple recent infarcts that involved the frontal lobes, right caudate nucleus, and putamen. Post mortem cultures were positive for A. kalrae.

CASE REPORT

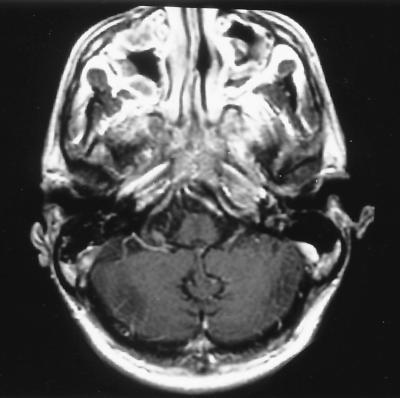

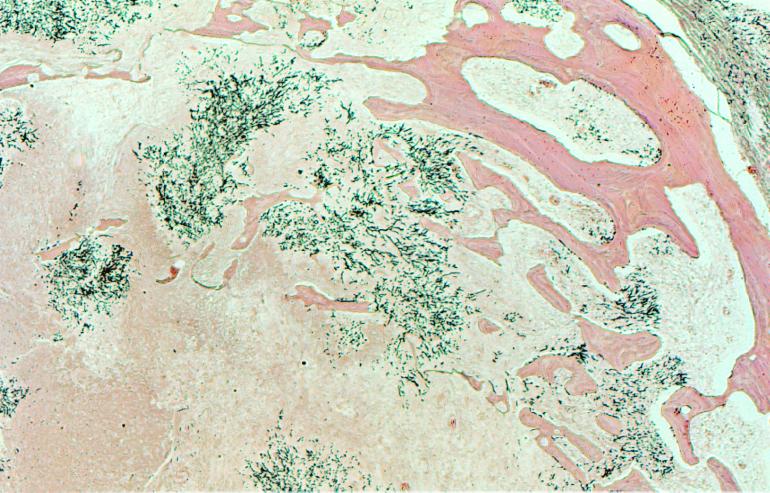

The patient was a 33-year-old man with AIDS (CD4+ T-cell count, 7 cells/μl; human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] type 1 [HIV-1] RNA viral load, 82,000 copies/ml) who was receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy and who was initially admitted to the hospital with a 4-day history of increasing bilateral retroorbital pain. The patient had just finished an 8-week course of nafcillin for osteomyelitis. The patient's past medical history included cytomegalovirus retinitis with left-eye blindness, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection, recurrent oral candidiasis, and chronic renal insufficiency. The patient's medications included saquinavir, nelfinavir, lamivudine, azithromycin, ethambutol, ganciclovir, filgrastim, epoetin alfa, nystatin, and fluconazole. A computed tomography scan showed severe maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinusitis. The patient was initially started on piperacillin-tazobactam, and nafcillin was restarted. Eventually, the patient was discharged and was given ciprofloxacin and clindamycin, with symptomatic improvement. Two weeks later the patient was readmitted to the hospital with altered mental status secondary to acute on chronic renal failure that improved with dialysis. However, the patient had been complaining of persistent headaches and retroorbital pain; thus, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) of his brain including orbital-sinus cuts was obtained. This showed persistent extensive pansinus disease. There was also a hyperintensity at the superior aspect of the left sphenoid sinus, which resulted in concern that a focal “fungus ball” may have been present. There was also abnormal enhancement of the dura along the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, suggesting intracranial extension of sinus disease. The frontal lobes and cavernous sinuses were normal in appearance. The patient underwent an endoscopic sphenoidotomy and biopsy that revealed hyphal forms. The patient was then started on itraconazole. Cultures of the purulent material from the left sphenoid revealed Arthrographis kalrae. Subsequent MRIs over the following 3 months essentially showed no interval change (Fig. 1). As there was still no evidence of extension into the frontal lobe parenchyma, itraconazole therapy was continued. Five months after the patient first presented with sinusitis, he was admitted for respiratory distress, but unfortunately, he died as a result of enterococcal sepsis and P. carinii pneumonia. Notably, postmortem examination also revealed invasive fungal sinusitis involving the sphenoid sinus and extending through the cribiform plate into the inferior surfaces of the bilateral frontal lobes (Fig. 2). There was also an associated fungal meningitis and vasculitis with fungal thrombosis and multiple recent infarcts involving the frontal lobes, the right caudate nucleus, and the putamen. Postmortem cultures were positive for A. kalrae.

FIG. 1.

MRI axial T1-post gadolinium image showing pansinus disease in maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses. Also noted is a destructive soft-tissue mass centered at the roof of the sphenoid sinus, with extension along the dura of the anterior cranial fossa

FIG. 2.

Silver stain demonstrating hyphal invasion of the sphenoid bone (print courtesy of Amy Heerema, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco).

Microbiology.

Operatively obtained sphenoid fluid was plated in the microbiology laboratory onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (Emmons), inhibitory mold agar, and brain heart infusion agar (Remel, Lenexa, Kan.). The media were incubated at 30°C. After 48 h of incubation, cream-colored, glabrous colonies were observed. Microscopically, elongated oval budding yeast cells were seen. The germ-tube test was negative. Since the initial morphology appeared yeast-like, the isolate was inoculated onto an API 20C AUX identification strip (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). After 72 h of incubation only glucose was assimilated, generating an API 20C AUX profile number of 2000000. According to the manufacturer's database, this profile number is listed as “good likelihood but low selectivity” for Blastoschizomyces capitatus, Candida krusei, Torulopsis glabrata, Candida lambica, and Hanseniaspora valbyensis. Since this profile is close to those for more than one taxon stored in the database, the manufacturer specifies that additional criteria must be used to verify the identification. Additional tests and the slowly emerging morphology of the isolate were not consistent with any of the suggested organisms, and in fact, A. kalrae is not included in the API 20C AUX database.

The fungus was weakly urease positive, was resistant to cycloheximide, did not assimilate nitrate, and grew at 37°C. After 5 days of incubation, the cream-colored glabrous colonies became velvety due to formation of hyphae and developed a pale yellow reverse. Elongate oval blastoconidia, septate hyaline hyphae, and simple rectangular arthroconidia on conidiophores and intercalary in the hyphae were observed (Fig. 3) in slide culture preparations stained with Myco-Perm Red (Scientific Device Lab, Inc., Glenview, Ill.). The slide cultures were grown on cornmeal agar with Tween and potato dextrose agar with thiamine (Remel). The isolate was then referred to the Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, for identification and susceptibility testing. There the isolate was accessioned into the stock collection as UTHSC 97-2663 and was subcultured onto potato flakes agar (PFA) slants, a PFA plate, and a PFA slide culture (prepared in-house) (11). Colonies on PFA at 25°C were initially cream and moist with a yeast-like appearance, but after 7 days of incubation they became beige, flat, and powdery to granular in texture. Temperature studies performed on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Remel) revealed that growth occurred at 25, 35, and 42°C, with moist colonies present at 42°C. Cycloheximide tolerance was demonstrated by growth on Sabouraud dextrose agar medium containing cycloheximide (Remel). Microscopically, the isolate produced hyaline, septate hyphae; unbranched and irregularly branched (dendritic, i.e., tree-like) conidiophores; chains of one-celled, rectangular arthroconidia (2 by 4 μm) not separated by disjunctor cells; and occasional hyaline, sessile, subglobose conidia (4 by 5 μm) along the sides of the hyphae. On the basis of the characteristics presented above the isolate was identified as A. kalrae (13, 17). In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing performed by the previously published National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards M27-A reference method (7) indicated susceptibility to amphotericin B, fluconazole, and itraconazole with MICs at 48 h of 0.25, 8, and ≤0.015 μg/ml, respectively.

FIG. 3.

A. kalrae. A slide culture was stained with Myco Perm Red (Scientific Devices).

Discussion.

Invasive fungal sinusitis due to aspergillosis and zygomycosis was reported in immunocompromised patients before the AIDS era (6). Bacterial sinusitis occurs more commonly in HIV-seropositive individuals whose CD4 T-cell counts are greater than 350 cells/μl than in the HIV-seronegative population (4). Individuals with a history of recurrent bacterial sinusitis may develop thickening of the mucosa, which leads to chronic sinusitis and colonization of the airway with mold secondary to frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Although still uncommon in patients with AIDS, invasive fungal sinusitis might increase in incidence because patients are now surviving longer on highly active antiretroviral therapy and are on prolonged courses of antibiotics for recurrent bacterial infections and/or prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (6).

This is the first report implicating A. kalrae as an invasive pathogen in a patient with sinusitis. A. kalrae can be isolated from soil and compost, but only rarely has it been a possible human pathogen. A. kalrae has been described as a pathogen in the dorsal hand (eumycetoma), lung (in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid), and a corneal ulcer and as a cause of keratitis (1, 8, 12; R. McAleer, J. H. Froudist, and G. Cherian, X Congr. Int. Soc. Hum. Animal Mycol. abstr. 172, 1988). There has been some suggestion that a deficiency in cell-mediated immunity may be a predisposing factor (8). Of note, Tewari and MacPherson (18) demonstrated that Oidiodendron kalrai (previous taxonomy) can cause invasive disease of multiple organs and the brain in mice following intravenous and intraperitoneal injection of the organism.

The anamorphic (asexual) genus Arthrographis Cochet ex Sigler & Carmichael consists of five species: A. kalrae, A. cuboidea (13), A. lignicola (14), A. pinicola (15), and A. alba (3). The teleomorph of the type species, A. kalrae, is Eremomyces langeronii in the order Loculoascomycetes, family Eremomycetaceae (5). No mating attempts were made with the case isolate. A. alba is distinguished from A. kalrae by being white, failing to grow at 37°C, and lacking a Trichosporiella synanamorph. A. cuboidea is distinguished by more rapid growth and cube-shaped arthroconidia. A. lignicola is distinguished by broader yellow arthroconidia, while A. pinicola forms conidiomata and fails to grow on media containing cycloheximide.

In patients with AIDS, sinusitis is more common and more resistant to treatment than sinusitis in immunocompetent hosts (4, 6). The etiology is still predominantly bacterial, with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis commonly invoked. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are other pathogens that have been isolated. P. aeruginosa, an uncommon pathogen in immunocompetent patients, can account for as much as 17% of cases of acute sinusitis and 20% of cases of chronic sinusitis in the HIV-infected population (4). Bacterial sinusitis can occur at any CD4 count, but as CD4 counts decline, sinusitis becomes more chronic. Fungal sinusitis is rarely reported and typically occurs in patients with CD4 counts less than 150 cells/μl. A recent report of sinusitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in an AIDS patient (2) reviewed 24 other cases of fungal sinusitis via a MedLine search: 19 were caused by Aspergillus species, with the others caused by Schizophyllum commune, Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, Rhizopus arrhizus, and Pseudallescheria boydii (asexual stage, Scedosporium apiospermum). Alternaria alternata has also been reported to be a cause of sinusitis (5). Management of fungal sinusitis in AIDS patients remains controversial, with many advocating both surgical drainage and antifungal chemotherapy. Endoscopic sinus surgery is an outpatient procedure with minimal morbidity that has allowed many more patients to become eligible for biopsy and to have improved sinus drainage (4, 16). The choice of antifungal agent is unclear, with no randomized trials conducted given the low prevalence. In Aspergillus sinusitis, itraconazole has been reported to be an effective alternative to amphotericin B, with various levels of success (6). Although the role of antifungal susceptibility testing has not been well validated and it is not known how well MICs translate into clinical efficacy (9), it is generally accepted that factors other than the MIC alone may significantly affect the outcome. These factors include the pharmacokinetics of the drug, general host factors, sites of infection, and the virulence of the pathogen (10). Above all, despite the most aggressive and combined therapy, fungal sinusitis can be a relentlessly progressive disease. The case described here demonstrates that A. kalrae has the potential to cause invasive sinusitis in an immunocompromised host.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, University of California San Francisco—Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology Center for AIDS Research (P30 MH59037).

REFERENCES

- 1.Degavre B, Joujoux J M, Dandurand M, Guillot B. First report of mycetoma caused by Arthrographis kalrae: successful treatment with itraconazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:318–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckburg P B, Zolopa A R, Montoya J G. Invasive fungal sinusitis due to Scedosporium apiospermum in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:212–213. doi: 10.1086/520164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gené J, Guillamón J M, Ulfig K, Guarro J. Studies on keratinophilic fungi. X. Arthrographis alba sp. nov. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:1185–1189. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K C, Tami T A. Otolaryngologic manifestations of HIV disease. In: Cohen P T, Sande M A, Volberding P A, editors. The AIDS knowledge base. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 564–567. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malloch D, Sigler L. The Eremomycetaceae (Ascomycotina) Can J Bot. 1988;66:1929–1932. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer R D, Gaultier C R, Yamashita J T, Babapour R, Pitchon H E, Wolfe P R. Fungal sinusitis in patients with AIDS: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1994;73:69–78. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman E M, Binns L. Intense photophobia caused by Arthrographis kalrae in a contact lens-wearing patient. Am J Opthalmol. 1997;123:547–549. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfaller M A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M G. Antifungal susceptibility testing: technical advances and potential clinical applications. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:776–784. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex J H, Pfaller M A, Galgiani J N, Bartlett M S, Espinel-Ingroff A, Ghannoum M A, Lancaster M, Odds F C, Rinaldi M G, Walsh T J, Barry A L Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:235–247. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinaldi M G. Use of potato flakes agar in clinical mycology. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1159–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1159-1160.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigler L, Kennedy M J. Aspergillus, Fusarium, and other opportunistic moniliaceous fungi. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 1212–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigler L, Carmichael J W. Taxonomy of Malbranchea and some other hyphomycetes with arthroconidia. Mycotaxon. 1976;4:349–488. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigler L, Carmichael J W. Redisposition of some fungi referred to Oidium microspermum and a review of Arthrographis. Mycotaxon. 1983;18:495–507. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigler L, Yamaoka Y, Hiratsuka Y. Taxonomy and chemistry of a new fungus from bark beetle infected Pinus contorta var. latifolia. Part 1. Arthrographis pinicola sp. nov. Can J Microbiol. 1990;36:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sooy C D. Impact of AIDS on otolaryngology head and neck surgery. In: Meyers E N, editor. Advances in otolaryngology. Head and neck surgery. Vol. 1. Chicago, Ill: YearBook; 1987. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Guide to clinically significant fungi. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tewari R P, MacPherson C R. Pathogenicity and neurological effects of Oidiodendron kalrai for mice. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:1130–1139. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.3.1130-1139.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]