Abstract

Introduction

We assessed students' perception of the impact of the pandemic on their well-being, education, academic achievement, and whether grit and resilience alter students’ ability to mitigate the stress associated with disruptions in education. We hypothesized that students would report a negative impact, and those with higher grit and resilience scores would be less impacted.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team of educators created and distributed a survey to medical students. Survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and multivariate linear regressions. A p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 195 students were included in the study. Approximately 92% reported that clinical education was negatively affected, including participants with higher grit scores. Students with higher resilience scores were more optimistic about clinical education. Those with higher resilience scores were less likely to report anxiety, insomnia, and tiredness.

Conclusion

More resilient students were able to manage the stress associated with the disruption in their education. Resiliency training should be year-specific, and integrated into the UME curriculum due to the different demands each year presents.

Keywords: Well-being, Grit, Resilience, Medical student education, Undergraduate medical education, COVID-19 pandemic

1. Introduction

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has had monumental implications for undergraduate medical education (UME) in the United States. Medical schools have been challenged to continue rigorous didactic and clinical education while minimizing risk to students, faculty, staff, and patients. In March of 2020, the Association of American Medical colleges (AAMC) recommended that medical students not be involved in direct patient care and identified students as “non-essential workers.”1 The AAMC guidance was based on three concerns: public health, access to PPE, and risk of exposure to Covid-19 for patients, students, and providers.2 These radical changes in UME were unlike anything seen in recent years, leading students to express concern over the delivery of their education and personal risks related to coronavirus exposure during the pandemic.2

It has been well documented that students experience stress and anxiety due to the nature and rigor of medical school.3 Sources of medical students' stress are work-life balance, relationships, lack of guidance and support, the volume of information presented, financial concerns, and uncertainty of the future.4 The true impact of the pandemic on UME is still in flux; however, presumably, it is negative. It is also unclear if the added stress from the pandemic has impacted students uniformly or if protective factors, such as “Grit” and “Resilience,” aid some students’ ability to cope better than others.

Resilience is a psychological characteristic defined by coping effectively with acute and chronic stress, responding positively to challenges, and bouncing back from hardship.5 Resilience has been shown in the literature to be protective against long-term psychological disturbances, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and burnout.6 , 7 It is also associated with such characteristics as cognitive flexibility, a positive worldview, and optimism despite traumatic stressors.6 , 7

Grit is a related psychological characteristic and is defined as the perseverance to pursue long-term goals through adversity.8 , 9 Research has shown that grit is positively associated with student performance in gross anatomy, a higher score on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 CK, and is associated with shorter time to graduate degree completion.10 , 11

While there are similarities between these two psychological constructs, grit refers to the sustained commitment to achieving goals despite adversity, and resilience is coping with challenges. Interestingly, one recent study found grit and resilience to both be protective against the increased stress among faculty and residents during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.12

This study aimed to identify the impact of the pandemic on medical students' self-reported well-being, ability to reach academic milestones (i.e., USMLE Step examinations and graduation), and future residency applications. The study also aimed to measure students' grit, resilience and to identify associations of these traits with students’ perceptions of the impact of the pandemic on their education.

2. Methods

A multidisciplinary team of educators at a single medical school, created a 39-item electronic survey using the Qualtrics survey platform (Qualtrics Software Company, Provo, UT). The survey included demographic questions, the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S), the 2-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-2), and questions designed to assess the impact of the pandemic on psychological well-being and achievement of academic milestones. Grit-S is an 8-item tool that requires participants to rate statements regarding passion and perseverance to pursue long-term goals using a 5-point Likert scale.13 The Grit-S tool is highly correlated with the original 12-item grit scale, has strong internal consistency, and has high test-retest reliability.14 The CD-RISC-2 is a 2-item measure of resilience where participants rate statements regarding their ability to bounce back from hardships and their adaptability to challenges using a 5-point Likert scale. The CD-RISC-2 has high test-retest reliability, strong divergent and convergent validity, and a strong correlation to the full version of the tool.14 Both the GRIT-S and CD-RISC-2 possess strong validity evidence to assess grit and resilience among adults. Before distributing the survey, the study tool was pilot tested with medical school leadership to ensure that the questions were intuitive, the survey flow was logical, and the response anchors were consistent throughout. See Supplemental Figure A to view the survey.

After IRB approval, the survey was distributed through the weekly “School of Medicine” online newsletter and also via a student-organized text communication application. Data were collected from June 27 through July 15, 2020. The survey was re-distributed four times. The timing of the survey was two months after the first peak of COVID in the region, and three months after “non-essential” workers (i.e. medical students) were removed from healthcare environments. First-year students were excluded from the study as their medical studies had not yet commenced.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continuous data, and total counts were tabulated for categorical data. Missing data were addressed using the pairwise deletion method. Scores from the grit and resilience tools and all Likert scale responses were treated as continuous data because there was a sufficient sample size of more than ten observations per group. This enabled the use of parametric analysis.15 , 16 Likert scale responses were coded to a scale of −2 to +2. Positive values (+1 and + 2) represented a positive response (agree, strongly agree). Negative values (−1 and −2) represented a negative response (disagree, strongly disagree), and a response of 0 represented a neutral response (neither agree nor disagree).

An ANOVA test was utilized to examine demographic differences between participants’ year in medical school. To identify how the pandemic affected students, linear regression analyses for each dependent variable (questions regarding emotions and stressors) while accounting for confounders such as year of medical school (MS2, MS3, MS4) and grit and resilience scores. MS2 students were the reference group for the statistical analyses.

Free-response answers to the question “Any further comments?” were qualitatively analyzed for common themes. Themes were coded and analyzed using the content analysis method by two raters. All quantitative statistical tests were performed using SPSS statistical software, Version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY) with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 198 students completed the survey. The final statistical analysis included 195 students for a response rate of 13.8%. Two respondents were excluded because they were first-year students, and one was excluded as an outlier due to the reported age of 65. All survey items were completed by 97% (n = 190/195) of respondents. Response rates per cohort were 20% of MS2, 19% of MS3, and 12% of MS4. The average age of the participants was 24.9 years. See Table 1 for additional demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics stratified according to medical school year.

| Cohort | Respondents No. (%) | Indianapolis Campus No. (%) | Female No. (%) | Living Alone No. (%) | Age | Grit | Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS2 | 75 (38) | 29 (39) | 49 (65) | 30 (40) | 23.8 ± 2.2 | 30 ± 3.8 | 8.4 ± 1 |

| MS3 | 66 (33) | 50 (76) | 40 (61) | 17 (26) | 25.1 ± 1.8 | 30.4 ± 3.4 | 8 ± 1.3 |

| MS4 | 43 (22) | 40 (93) | 27 (63) | 7 (16) | 26.7 ± 6.2 | 29.8 ± 4.1 | 8 ± 1.4 |

| Total | 184 (100) | 119 (64.7) | 116 (63) | 54 (29.3) | 24.9 ± 3.7 | 30.1 ± 3.7 | 8.2 ± 1.2 |

*Two students reported being in the first year of medical school and were excluded.

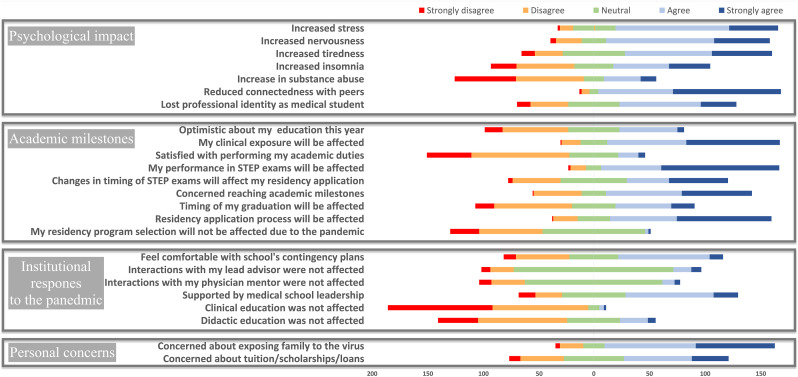

Most students (54%) reported that stress in all aspects of their lives was “high” or “very high” at the time of questionnaire completion, and 75% agreed or strongly agreed they experienced an increase in stress due to the pandemic (Fig. 1 ). MS3 and MS4 students reported a more significant increase in stress than MS2 students. Many students reported increased anxiety/nervousness (75%), tiredness/exhaustion (68%), and sleep disturbances (45%). Multivariate analysis revealed pandemic-induced stress was less prominent among students with a higher resilience score after adjusting for confounders such as year in school, campus location, and living situation. Students with a higher resilience score reported less physical and psychological symptoms of anxiety, tiredness, and sleep disturbances. Of note, MS3 students had lower resilience scores than MS2 students (P < .001).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of survey responses.

Precisely 92% of students reported that the pandemic negatively affected their clinical education, including those with higher grit scores who also perceived a negative impact (coefficient = −0.198, P = .02). Students with higher resilience scores were more optimistic about clinical experiences (coefficient = −0.197, P = .02), while 60% of students reported that didactic education was negatively affected. Regarding perceived support from leadership, 52% of students replied positively, but students with a higher grit score reported feeling less supported at this stage of the pandemic.

Concern about milestone achievement was reported by 67% of students and was less prevalent among MS4 students and those with a higher resilience score. Most students reported worry about their performance on USMLE Step exams (82%) and academic performance overall (28%). The concern related to USMLE Step exam performance was greatest among MS3 students and less prevalent among students with higher resilience scores (coefficient = 0.206, P = .01). Students indicated that they worried changes to the timing of USMLE Step exams would negatively impact the residency application process (47%), especially third-year students. ( Table 2 ). Students perceived suspension of away rotations would negatively impact their residency program selection (42%), with MS4 (coefficient = −0.181, P = .03), and this concern was highest among students at regional campuses (coefficient = −0.178, P = .02). Students (36%) expressed worry that the pandemic would ultimately affect the timing of graduation. This concern was more prevalent among females (coefficient = −0.208, P = .006), and less prevalent in students with a lower resilience score (coefficient = −0.252, P = .002).

Table 2.

Perceived impact of COVID-19 on exam performance, residency applications and timing of graduation.

| Concern about Step Performance |

Concern about Step Timing on Residency Applications |

Concern about achieving Academic Milestones |

Effects on Residency Application Process |

Concern about Timing of Graduation |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Mean ± SD | Coef | p-value | Mean ± SD | Coef | p-value | Mean ± SD | Coef | p-value | Mean ± SD | Coef | p-value | Mean ± SD | Coef | p-value |

| MS2 | 1.1 ± 1 | Ref | Ref | 0.2 ± 1 | Ref | Ref | 0.9 ± 1.1 | Ref | Ref | 0.6 ± 1.1 | Ref | Ref | −0.2 ± 1.2 | Ref | Ref |

| MS3 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.285 | 0.001 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.337 | <0.001 | 1 ± 1.1 | 0.04 | 0.59 | 1.2 ± 1 | 0.25 | 0.001 | 0 ± 1.2 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| MS4 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 0.033 | 0.69 | 0.3 ± 1.3 | 0.76 | 0.35 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | −0.26 | 0.001 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 0.1 ± 1.2 | 0.13 | 0.1 |

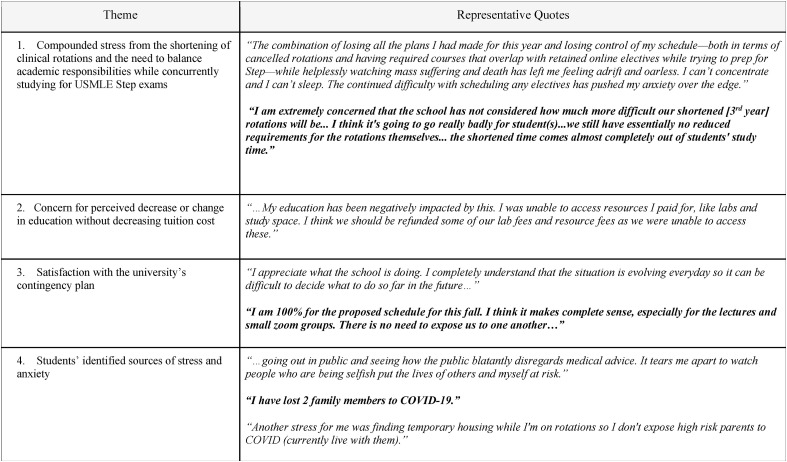

The pandemic negatively affected many students' sense of purpose, with 84% reporting loss of professional identity due to changes in their educational experience. Only 12% of students reported satisfaction with personal academic performance, with resilience being a protective factor (coefficient = 0.220, P = .007). Approximately 84% of students reported a reduced connectedness among peers, and 26% reported increased alcohol use and other substances. Student loans were a concern for 48% of students. Interestingly, students with a higher grit score reported more worry related to student loans (coefficient = 0.279, P < .001), and MS3 students reported less financial concern regarding student loans (coefficient = −0.173, P = .04). Thirty-four students wrote free-text comments, and four major themes emerged. The first theme is the compounded stress from the shortening of clinical rotations and the need to balance academic responsibilities while concurrently studying for USMLE Step exams. The second theme was a concern for perceived decrease or change in education without decreasing tuition cost. The third theme reflected students’ satisfaction with contingency plans. Student-identified sources of stress comprised the fourth theme of the free-text comments ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Exemplary quotes representative of themes.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has distinctly impacted medical students' self-reported well-being, academic achievement, and residency application process. The results of this study reveal that students' pre-pandemic concerns related to academic achievement and career planning were compounded by personal stressors, disconnection from peers, and loss of professional identity because of changes in their education due to pandemic contingency plans. Resilience was protective over a perceived negative impact on academic achievement during a global pandemic in this cohort, but grit was not. There was variability among medical students’ perceptions of the impact of the pandemic on education among each year of students, especially third year students who reported the most psychologic distress because of pandemic changes to their education.

It is not surprising that more resilient students had a less negative perception of their academic circumstances, however it is interesting that a high grit score was not associated with a better outlook. Resilience was likely to be more protective over psychological well-being than grit because resiliency better provides the ability to cope with adversity. Similarly, resilience was more protective than grit in another study of faculty and resident physicians at a large academic medical center during the COVID-19 pandemic.12 The findings purport the potential for resilience training to improve students’ perceptions of adversity and their ability to navigate disruptions in their education. Likewise, grit and resilience are associated with improved academic performance during medical school.17

There was variability observed between students’ perceptions of the impact of the pandemic on medical education based on their medical school year. This variability is not surprising due to the curricular differences in medical school year (i.e. primarily didactic vs primarily clinical). MS2 students perceived less impact of the pandemic on their educational experience; however, these students routinely have online didactic courses, so this was not radically changed during the pandemic. Since they perceived less of an educational interruption, MS2 student perceptions of the overall impact of the pandemic was lower than students in more clinically focused years of medical school, specifically MS3s and MS4s.

MS3 students reported the most overall concern about the impact of the pandemic on all aspects of their education. MS3's have also reported the lowest psychological well-being. This finding contrasts with other literature that reports the highest rate of anxiety and depression is found among MS2 students and is subsequently attributed to the stress related to the USMLE Step 1 exam and transition to clinical rotations.18 , 19 Since stressors that have traditionally occurred during the second year occurred during year three due to COVID-19 pandemic related delays; the timeline shift is one potential explanation for the discrepancy compared to previous data.

MS4 students perceived a potential negative impact of canceling away rotations and how that might affect their residency application and match process. Another study of medical students reported similar findings on the perceived impact of the loss of away rotations, specifically to procuring letters of recommendation.20 In this study, 17% of respondents said they were more likely to take an extra research year to bolster their application before applying to residency.20

Educational training programs designed to enhance resilience, decrease stress and mitigate burnout over time have been shown to improve performance and perceived well-being20 but should be tailored to each year if medical school's unique stresses and demands. Since third-year students have lower resilience scores than students in other years of medical school, targeted interventions to promote or enhance resilience in this cohort may be particularly beneficial. Future research to explore the efficacy of resiliency training implementation may reveal it's utility for medical students in each year of school.

Future research in this arena should focus on the efficacy of focused resilience training to boost well-being in future potential adverse events like a global pandemic. A longitudinal study of grit and resilience scores of students enrolled in resilience training, academic performance, and perceived well-being would provide a deeper understanding of the efficacy of resilience training to mitigate the adverse effects of the diverse challenges in medical school. Research to determine the detriment of loss of away rotations would inform medical educators of the importance of away rotations to students’ residency applications and match outcomes.

Limitations to this study are the cross-sectional, single institution design, and low response rate. Due to the cross-sectional nature, the results cannot measure a change in grit or resilience scores due to the pandemic, nor can the students' perceptions be correlated with actual outcomes. Additionally, a more robust design would be a longitudinal study because individual resilience fluctuates relative to one's circumstances.

Another limitation to this study was a low response rate which can be attributed to electronic survey distribution. Despite a low response rate, the sample size was substantial (n = 195), which the researchers deemed sufficient to examine statistical data. Since the response rate is low, it is essential to consider selection bias as an additional potential limitation. The study institution is large and widespread across the state in many different communities, but despite this the study is limited because it is a single-institution study.

5. Conclusion

While the lasting impact of COVID-19 on medical education is yet to be determined, in this study, more resilient students were able to better handle the stress associated with a disruption in their medical education. Resiliency training should be integrated into the UME curriculum to prepare medical students to overcome adversity and should be year-specific due to the different psychological, academic, and clinical demands each year presents. The results of this study provide insight for medical educators to improve students’ support to navigate stressors and changes that will be vital to improving coping, adaptability, and perceived well-being as a future physician.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Kristen Heath for your assistance with survey creation and distribution. Additional acknowledgment and appreciation for contributions from Theoklitos Kiripi, and Edward Hernandez for their assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.01.022.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Whelan A., Prescott J., Young G., Catanese V.M., McKinney R. Guidance on medical students' participation in direct patient contact activities. Association of American medical colleges. Aug 14, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-04/meded-April-14-Guidance-on-Medical-Students-Participation-in-Direct-Patient-Contact-Activities.pdf Published.

- 2.Menon A., et al. “Medical students are not essential workers: examining institutional responsibility during the COVID-19 pandemic.”. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1149–1151. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Supe A.N. A study of stress in medical students at Seth G.S. Medical College. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill M.R., Goicochea S., Merlo L.J. In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1530558. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1530558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connor K.M., Davidson J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mealer M., Jones J., Moss M. A qualitative study of resilience and post-traumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1445–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mealer M., Jones J., Newman J., McFann K.K., Rothbaum B., Moss M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: results of a national survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duckworth A. Scribner; New York: 2016. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. First Scribner hardcover edition. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duckworth A.L., Peterson C., Matthews M.D., Kelly D.R. Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fillmore E., Helfenbein R. Medical student grit and performance in gross anatomy: what are the relationships? Faseb J. 2015;29(1_supplement) 689–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller-Matero L.R., Martinez S., MacLean L., Yaremchuk K., Ko A.B. Grit: a predictor of medical student performance. Educ Health. 2018;31:109–113. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_152_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman E.M., Athanasiadis D.I., Anton N.E., et al. How resilient is your team? Exploring healthcare providers' well-being during the COVID-19pandemic. Am J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.09.005. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duckworth A.L., Quinn P.D. Development and validation of the short grit scale (grit-s) J Pers Assess. 2009;91:166–174. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaishnavi S., Connor K., Davidson J.R. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatr Res. 2007;152:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamieson S. Likert scales: how to (ab)use them. Med Educ. 2004;38(12):1217–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in health sciences education. Theor Pract. 2010;15(5):625–632. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chisholm-Burns M.A., Berg-Poppe P., Spivey C.A., Karges-Brown J., Pithan A. Systematic review of noncognitive factors influence on health professions students' academic performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021 Oct;26(4):1373–1445. doi: 10.1007/s10459-021-10042-1. Epub 2021 Mar 26. PMID: 33772422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosal M.C., Ockene I.S., Ockene J.K., Barrett S.V., Ma Y., Hebert J.R. A longitudinal study of students' depression at one medical school. Acad Med. 1997 Jun;72(6):542–546. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00022. PMID: 9200590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrnes Y.M., Civantos A.M., Go B.C., McWilliams T.L., Rajasekaran K. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study. Med Educ Online. 2020 Dec;25(1):1798088. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1798088. PMID: 32706306; PMCID: PMC7482653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistretta E.G., Davis M.C., Temkit M., Lorenz C., Darby B., Stonnington C.M. Resilience training for work-related stress among health care workers: results of a randomized clinical trial comparing in-person and smartphone-delivered interventions. J Occup Environ Med. 2018 Jun;60(6):559–568. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001285. Erratum in: J Occup Environ Med. 2018 Aug;60(8):e436. PMID: 29370014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.