Abstract

Drug-associated sensory cues increase motivation for drug and the orexin system is importantly involved in this stimulus-enhanced motivation. Ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a major target by which orexin signaling modulates reward behaviors, but it is unknown whether this circuit is necessary for cue-driven motivation for cocaine. Here, we investigated the role of VTA orexin signaling in cue-driven motivation for cocaine using a behavioral economics (BE) paradigm. We found that infusion of the orexin-1 receptor (Ox1R) antagonist SB-334867 (SB) into VTA prior to BE testing reduced motivation when animals were trained to self-administer cocaine with discrete cues and tested on BE with those cues. SB had no effect when animals were trained to self-administer cocaine without cues or tested on BE without cues, indicating that learning to associate cues with drug delivery during self-administration training was necessary for cues to recruit orexin signaling in VTA. These effects were specific to VTA, as injections of SB immediately dorsal had no effect. Moreover, intra-VTA SB did not have an impact on locomotor activity, or low- or high-effort consumption of sucrose. Finally, we microinjected a novel retrograde adeno-associated virus (AAVretro) containing an orexin-specific short hairpin RNA (OxshRNA) into VTA to knock down orexin in the hypothalamus-VTA circuit. These injections significantly reduced orexin expression in lateral hypothalamus (LH) and decreased cue-driven motivation. These studies demonstrate a role for orexin signaling in VTA, specifically when cues predict drug reward.

Subject terms: Addiction, Reward

Introduction

Drug-associated cues acquire motivational significance over time and can trigger relapse to drug seeking, even following protracted abstinence. The hypothalamic neuropeptide orexin (hypocretin) system has been linked to cue-dependent and highly motivated cocaine-seeking behaviors (for review, see refs. [1, 2]). Our lab established a role for the orexin system in drug demand using a behavioral economics (BE) paradigm, which provides a quantitative estimate of motivation. In this paradigm, a demand curve is fitted to lever-pressing data using an exponential demand equation [3] to generate two parameters of cocaine demand: demand elasticity (α), which inversely scales with motivation, and low-effort consumption (Q0) [4]. We previously found that removing cocaine-associated cues during BE testing decreased motivation for drug (increased α), and that this cue-enhanced motivation was dependent on orexin-1 receptor (Ox1R) signaling [5]. That study highlighted that Ox1R signaling is required for cue-dependent motivation, but it remained unclear when the orexin system was recruited during drug-cue learning or where in the brain orexin acted to promote motivation in response to drug-paired cues.

Ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a target that may mediate orexin’s effects on cue-driven motivation. VTA is innervated by orexin fibers and VTA neurons contain both orexin-1 and orexin-2 receptors [6, 7]. Ox1R signaling in VTA promotes responding for cocaine under high-effort conditions [8–10] and cue-induced cocaine seeking [11, 12]. Orexin potentiates glutamatergic responses of VTA dopamine (DA) neurons via signaling at Ox1Rs [13] and is necessary for drug-induced plasticity in the DA system [14, 15]. Therefore, Ox1R signaling in VTA may mediate motivation for cocaine by regulating glutamatergic signaling in response to drug-associated cues [16]. However, no studies have directly manipulated the orexin-VTA circuit to parse the importance of drug-related cues in the recruitment of this circuit.

Here, we utilized pharmacological and retrograde viral vector approaches to test the role of the orexin-VTA circuit in cue-driven motivation for cocaine, as assessed by BE demand testing. We trained animals to self-administer cocaine with or without drug-paired cues and transitioned them to BE testing with or without cues. We microinjected the Ox1R antagonist SB-334867 (SB) into VTA and observed that SB only impacted motivation when animals were trained to self-administer cocaine with cues. Intra-VTA SB did not have an impact on low-effort consumption of cocaine, motivated or low-effort sucrose taking, or locomotor activity. We also found that knockdown of orexin expression in VTA-projecting neurons using a novel retrograde adeno-associated virus (AAVretro) containing orexin short hairpin RNA (OxshRNA) similarly attenuated motivation during BE testing with discrete cues. Collectively, these studies highlight a role for Ox1R signaling in the orexin-VTA circuit in motivated, cue-dependent cocaine taking.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (weighing 300–325 g) were pair-housed on a 12 h reverse light : dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal facility at Rutgers University-Piscataway. Male rats were used so that we could directly compare results to previous studies from our laboratory, which investigated the role of orexin signaling in cue-driven cocaine demand in male animals [5, 17, 18]. In addition, recent results from our lab and others show that cocaine demand in female rats varies substantially with estrous cycle (Kohtz et al., unpublished observations), and that the estrous cycle has an impact on cue-driven demand in females [19]. Future studies across cycle phases will be needed to characterize the role of orexin signaling in cue-driven demand in females.

All animals were given ad libitum access to water and standard rat chow. Animals were acclimated for 2 days to the animal facility upon arrival and were handled for at least 3 days prior to surgery. All protocols and animal-care procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rutgers University-Piscataway.

Experiment 1: intracranial SB microinjections into VTA prior to BE testing with cues or without cues

Experimental BE cue/no-cue design

Three groups of animals were used to investigate the role of Ox1R signaling in cocaine demand with cues. Animals were trained on a fixed ratio-1 (FR1) schedule to self-administer cocaine with (Groups 1 and 2) or without (Group 3) discrete light and tone cues paired with cocaine infusions (3.6 s; 0.2 mg/50 µl) following a response on the active lever. Animals were then trained on BE for a minimum of 6 days until stability criteria were reached with (Group 1) or without cues (Groups 2 and 3); baseline BE parameters were the average α and Q0 values across the last three sessions. The house light remained on for all groups during the self-administration sessions. All groups were then tested for demand following intra-VTA microinjections of the Ox1R antagonist SB or its vehicle (artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)) in a counterbalanced design (details below). SB/aCSF was microinjected immediately before BE tests, which were conducted with (Group 1) or without cues (Groups 2 and 3). After receiving both aCSF and SB treatments, subjects were re-stabilized on BE with (Groups 2 and 3) or without (Group 1) cues and were tested with SB and aCSF (counterbalanced). To determine how cues impacted demand, we compared animals’ last stable demand parameters with (Group 1) or without (Groups 2 and 3) cues to the first stable parameters with (Group 2 and 3) or without (Group 1) cues to capture behavioral effects from the cue-to-no cue (Group 1) or no cue-to-cue (Groups 2 and 3) transition.

Intra-VTA microinjections

All VTA microinjections were performed using injectors extending 2 mm past the guide cannulae. The injectors were kept in place for 1 min to allow for drug diffusion. All tests were counterbalanced and within-subjects.

Experiment 2: effects of SB microinjections dorsal to VTA

Dorsal microinjections

A separate group of animals underwent intracranial implantation of bilateral guide cannulae aimed at VTA, as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Dorsal control microinjections in this group were performed to ensure that effects following intracranial microinjections were not due to diffusion of liquid up the cannula tract. Injectors projecting 0.2 mm past the bottom of the guide cannula were inserted to infuse SB 1.8 mm dorsal to VTA (0.3 μl; 1 mM concentration dissolved in aCSF) immediately prior to BE testing. Dorsal microinjections were performed prior to intra-VTA SB microinjections, as described in previous publications [20, 21].

Intra-VTA microinjections

Following BE testing with dorsal SB microinjections, animals were re-stabilized on BE and tested with longer injection cannulae with tips in VTA; SB or aCSF intra-VTA microinjections were conducted in a counterbalanced design, as described above.

Experiment 3: effects of SB microinjections on locomotor activity and sucrose self-administration

Locomotor activity

Following testing on the BE procedure, animals were habituated to a locomotor chamber (clear acrylic, 40 × 40 × 30 cm) equipped with Digiscan monitors (AccuScan Instruments) as described previously [22]. Habituation sessions occurred for 2 h/day for 3 days. After habituation, rats received intra-VTA aCSF or SB and underwent locomotor testing. A 1-day washout period followed, in which rats were placed in the locomotor chamber without any treatment. Rats received either aCSF or SB the following day. Each animal received aCSF and SB in a counterbalanced manner.

Sucrose self-administration

Animals were trained to lever press for sucrose on an FR1 schedule for 2 h/day for a minimum of 5 days, as described previously [23]. These animals were also used in cocaine studies, but no animal received more than six microinjections into VTA. The house light remained on during the self-administration sessions, as in the cocaine self-administration studies. Active lever presses yielded one sucrose pellet (45 mg, Test Diet) with the same discrete light and tone cues used in cocaine self-administration experiments. A 20 s timeout followed each reward. Animals were trained until the numbers of active lever responses across 3 days differed by ≤25%. On subsequent test days, animals received intra-VTA SB or aCSF in a counterbalanced design immediately prior to the test session.

Sucrose BE procedure

Animals were trained to lever press for sucrose pellets in operant chambers with discrete light and tone cues present after active lever presses, as described above. Some of these animals were also used in cocaine studies (n = 4), but sucrose self-administration behavior (unpaired t-test, baseline α: t6 = 1.46, p = 0.20 and Q0: t6 = 1.18, p = 0.28) and treatment effects (percent change from baseline after VTA SB infusion, unpaired t-test, α: t6 = 0.83, p = 0.44 and Q0: t6 = 0.64, p = 0.55) did not differ between animals with vs. without cocaine experience. After FR1 training, rats underwent FR3, FR10, FR32, and FR100 training, each for a minimum of 3 days with a minimum of 60 lever presses/day. For BE testing, timeouts, and a reverse order of FR schedules were employed to limit satiety [24]. BE tests consisted of five 10-min periods per session, during which a fixed number of active lever presses resulted in sucrose reward. The first period consisted of FR100 and subsequent periods were FR32, FR10, FR3, and FR1, in that order. A 20- min timeout occurred after each period, during which levers were retracted and the house light was turned off. Rats were given at least six BE sessions on different days and were tested with either intra-VTA aCSF or SB immediately prior to sessions after α and Q0 were stable (values varied by ≤30% across the last three sessions). No animal received more than six microinjections into VTA.

Experiment 4: retrograde viral vector knockdown of orexin input to VTA

AAV vectors

We confirmed the importance of the orexin-VTA pathway in cue-associated motivation for cocaine by knocking down orexin expression via intra-VTA microinjections of an OxshRNA construct packaged in a retrogradely transported AAV virus (AAVretro). AAV viral vectors were produced by the Genetic Engineering and Viral Vector Core of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Expression of the OxshRNA sequence was placed under the control of the mouse ubiquitin 6 promoter with an enhanced green fluorescent protein tag under the cytomegalovirus promoter to label transduced cells. The OxshRNA sequence targeted the Orexin transcript (5′- GTCTTCTATCCCTGTCCTAGT-3′) with loop sequence 5′-AGTCGACA-3′. A scrambled sequence was used as a negative control (scrambled RNA (scRNA); 5′-GCTTACTTTCGGCTCTCTACT-3′) with loop sequence 5′-TGTCGACT-3′. The specificity of the OxshRNA construct was reported previously [25]. We validated the specificity of this AAVretro construct by unilaterally microinjecting 1 µl of AAVretro-OxshRNA or -scRNA through guide cannula directed at VTA at an infusion rate of 0.1 µl/min for 10 min. For all intracranial injections, injectors were held in place for 10 min to prevent diffusion of virus up the cannula tract.

Behavioral studies

One group of animals was perfused either 2, 4, or 6 weeks post infusion, as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. A second group of animals was trained to self-administer cocaine and stabilized on the BE procedure, as described above. These rats received 0.3 µl of AAVretro-OxshRNA or -scRNA (infusion rate of 0.1 µl/min) bilaterally through VTA-directed guide cannula and allowed to recover for 1 week post infusion. This volume was smaller than that used above to achieve more focused injections and minimize potential uptake from outside of VTA or floor effects of the virus on behavior. Rats were then given access to cocaine on the BE paradigm for a minimum of 3 days/week for 3 additional weeks to minimize withdrawal during the period required for AAVretro-OxshRNA to knock down orexin (weeks 2–4 post infusion). Then, BE testing was conducted for 5 days (1 session/day); α and Q0 values were averaged across the testing days and compared to pre-injection (baseline) values. Animals were tested on locomotor activity after BE testing, starting 6 weeks post injection. Locomotor tests consisted of a single test day after 3 days of habituation in locomotor chambers (described above).

Results

Experiment 1: Ox1R signaling in VTA is important for cocaine motivation only in animals trained to self-administer cocaine in the presence of discrete cues

We first determined whether cues were necessary for SB to decrease motivation for cocaine. We trained three groups of animals, as outlined in Fig. 1A. All rats were trained to lever press for cocaine on an FR1 schedule with (Groups 1 and 2) or without (Group 3) cues before being trained and tested on the BE procedure to measure cocaine demand with (Group 1) or without cues (Groups 2 and 3). During FR1 training, groups did not differ in the number of infusions (two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA): F2,18 = 0.13, p = 0.88; Supplementary Fig. S1A), active lever presses (two-way RM ANOVA: F2,18 = 0.11, p = 0.90, Supplementary Fig. S1B), or inactive lever presses (two-way RM ANOVA: F2,18 = 0.32, p = 0.73; Supplementary Fig. S1C). During BE training and testing, there were no group differences in animals’ initial (baseline) α (one-way ANOVA: F2,18 = 2.02, p = 0.16; Supplementary Fig. S1D) or Q0 values (one-way ANOVA: F2,18 = 0.32, p = 0.73, Supplementary Fig. S1E).

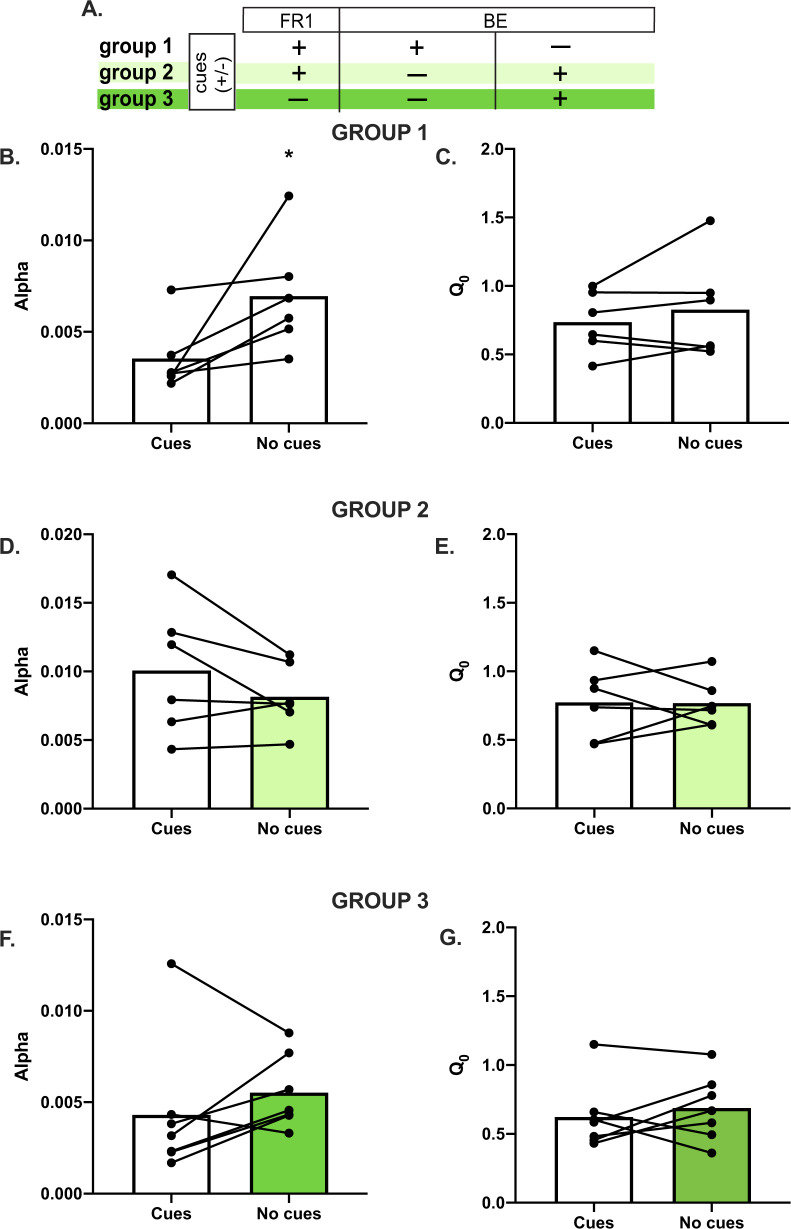

Fig. 1. Removal of discrete drug-paired cues reduced motivation in animals trained to associate drug delivery with cues.

A A schematic of cue and no-cue BE testing. Animals were trained on FR1 either with (+) or without (−) cues, as described in the text and indicated in the diagram. Animals were then trained on the BE procedure with cues (Group 1) or without cues (Groups 2 and 3) until stability criteria were reached. Cues were then removed (Group 1) or added (Groups 2 and 3) and behavior was re-stabilized for a minimum of 3 days to test the effects of cues on demand after training on the new BE procedure. B, C Animals trained and tested on the BE paradigm with cues (Group 1; n = 6) displayed increased α (decreased motivation) when cues were removed; Q0 was not affected (C). D, E Animals trained on FR1 self-administration with cues and the BE paradigm without cues (Group 2; n = 6) showed no change in α (D) or Q0 values (E) when cues were added during BE. F, G Animals trained on FR1 and BE without cues (Group 3; n = 7) showed no change in α (F) or Q0 values (G) when cues were introduced. *p < 0.05. Bar graphs indicate means ± SEMs.

We then sought to determine how removing (Group 1) or adding (Groups 2 and 3) cues impacted cocaine demand. In Group 1, changing from cue to no-cue BE significantly increased α (decreased motivation; Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test: W = 21.0, p = 0.03, Fig. 1B) but had no effect on Q0 values (paired t-test, t5 = 1.05, p = 0.34, Fig. 1C). In contrast, in Group 2, which was trained on FR1 with cues, switching from no-cue to cue BE did not have an impact on α (paired t-test: t5 = 1.60, p = 0.17, Fig. 1D) or Q0 (paired t-test: t5 = 0.05, p = 0.96; Fig. 1E). One animal from Group 2 was an extreme outlier (see Supplementary Materials and Methods) and therefore was excluded from overall analyses, but including this animal did not change the significance of our analyses (paired t-test, α: t6 = 1.15, p = 0.29; paired t-test, Q0: t6 = 0.45, p = 0.67; data not shown). In Group 3 (trained on FR1 and BE without cues), adding cues during BE testing did not alter α (Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test: W = 14.00, p = 0.30; Fig. 1F) or Q0 (Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test: W = 10.00, p = 0.47; Fig. 1G). Thus, overall, removing cues reduced motivation in animals previously trained on FR1 and BE with cues present, but adding these cues during subsequent BE performance did not have an impact on motivation if animals had been trained on BE without cues. Therefore, training with cues during FR1 and BE augments motivation on trials with cues and removing these cues reduces motivation in the BE paradigm.

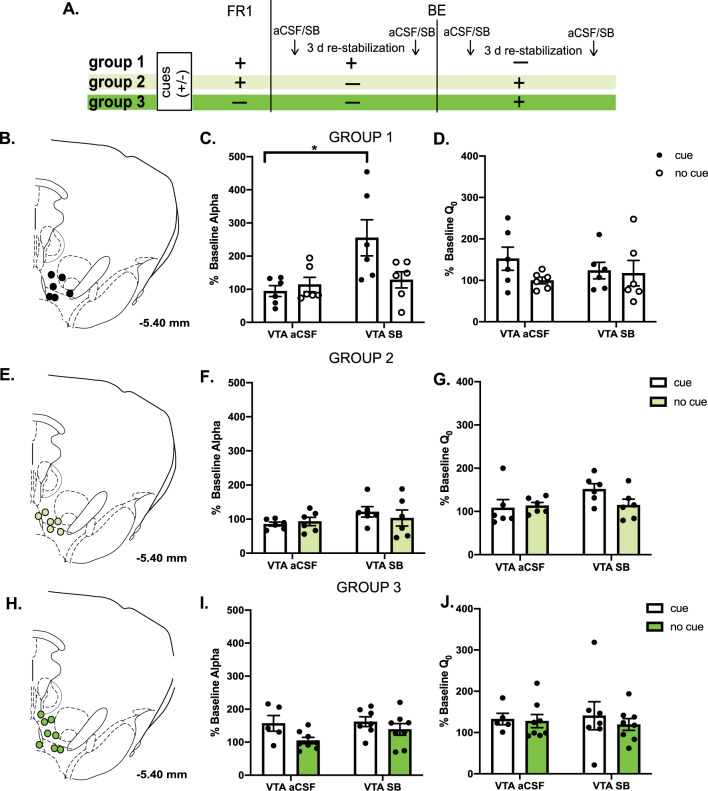

Next, we tested the effect of SB microinjections into VTA on cocaine demand with or without cues in each of the groups. In Group 1 animals (trained on FR1 and BE with cues, and tested on BE with cues first), there was a significant main effect of SB injection into VTA on α (two-way RM ANOVA: F1,5 = 9.85, p = 0.03; Fig. 2C) and a treatment × cue interaction (F1,5 = 8.45, p = 0.03). Post hoc tests revealed that SB increased α (reduced motivation) when injected into VTA prior to BE testing with cues (p < 0.05), but had no effect when injected prior to BE testing in these same animals in the absence of cues (Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests; p = 0.92) (Fig. 2C). There was no treatment × cue interaction for these VTA injections on Q0 (two-way RM ANOVA, treatment × cue interaction: F1,5 = 1.37, p = 0.30, Fig. 2D). In contrast, in Group 2 (trained on FR1 with cues and tested on BE without cues first), there was no treatment × cue interaction for α (two-way RM ANOVA: F1,5 = 4.00, p = 0.10, Fig. 2F) or Q0 (two-way RM ANOVA: F1,5 = 2.50, p = 0.18, Fig. 2G), indicating that SB was not effective during BE with cues in this group. We excluded one animal from Group 2 as a behavioral outlier (the same animal as above, see Supplementary Materials and Methods), but including this animal did not change the results of our analyses (two-way RM ANOVA, α treatment × cue interaction: F1,6 = 0.22, p = 0.66; Q0 treatment × cue interaction: F1,6 = 1.39, p = 0.28; data not shown). Similarly, in Group 3 (trained on FR1 without cues and BE without cues first), we did not observe a treatment × cue interaction for α (mixed-effects model, treatment × cue interaction: F1,3 = 1.75, p = 0.28; Fig. 2I) or Q0 (mixed-effects model, treatment × cue interaction: F1,3 = 0.16, p = 0.71; Fig. 2J; see Supplemental Methods, Data Analysis section). Three animals in Group 3 had to be removed from the study because they developed a sudden severe respiratory illness during the testing period and did not complete all four BE tests with aCSF/SB. Together, these data indicate that blockade of Ox1R signaling in VTA preferentially reduced cue-associated motivation for cocaine only in animals given cocaine-paired cues during BE training and testing.

Fig. 2. Intra-VTA SB lowered motivation for cocaine paired with discrete cues in animals trained to self-administer cocaine with cues.

A A schematic of testing with intra-VTA SB/aCSF during BE with or without cues. Animals were trained on FR1 either with (Groups 1 and 2) or without cues (Group 3), and then tested with intra-VTA aCSF/SB microinjections during BE either with (Group 1) or without cues (Groups 2 and 3). The same animals were then re-tested on subsequent sessions with aCSF/SB on BE either with (Groups 2 and 3) or without cues (Group 1). B–D Intra-VTA SB (injection sites in B) reduced motivation (increased α) in Group 1 animals (n = 6) only when cues were present (C). Intra-VTA SB had no effect on Q0 in these animals when tested with or without cues (D). Panels E-G - Intra-VTA SB (injection sites in E) did not reduce motivation in animals trained with cues and tested on BE first without cues (Group 2, n = 6; F). Intra-VTA SB had no effect on Q0 in Group 2 animals (G). H–J In Group 3 animals (trained on FR1 without cues; n = 5–8), SB (injection sites in H) did not have an impact on motivation (α; I) or low-effort consumption (Q0) on BE with or without cues present (J). *p < 0.05. Bar graphs indicate means ± SEMs.

Experiment 2: effects of intra-VTA SB infusions are not due to dorsal diffusion of SB

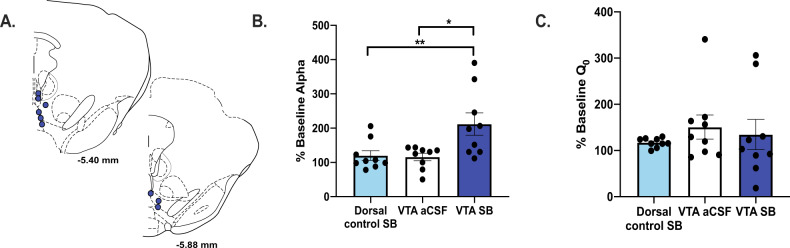

To ensure that the effects of intra-VTA SB microinjection were specific to VTA, in a separate cohort of animals we compared the effects of microinjecting SB into VTA vs. 1.8 mm dorsal to VTA (where the injectate would be expected to spread along the cannula tract). As we observed that the orexin-VTA projection only mediated motivation for cocaine in the presence of light-tone conditioned cues (described above), these studies were only conducted in animals trained and tested with cues. Consistent with our findings above, only intra-VTA SB microinjections reduced cocaine motivation (increased α); there was no effect of aCSF injection into VTA, or of SB injection dorsal to VTA on α (Friedman’s test: H3,9 = 10.89, p = 0.003; Dunn’s multiple comparisons, p < 0.05 vs. aCSF; p < 0.01 vs. dorsal SB; Fig. 3B). There was no effect of any treatment on Q0 (Friedman’s test: H3,9 = 3.56, p = 0.19; Fig. 3C). These results showed that the effects of SB on cue-associated cocaine motivation in Experiment 1 were mediated by Ox1R blockade specifically in VTA.

Fig. 3. SB increased cocaine demand elasticity (decreased motivation) when microinjected into VTA specifically.

A Plots of microinjection locations in VTA (a separate group than those in Figs. 1 and 2). Control microinjections (not depicted here) were made first in each of these animals, 1.8 mm dorsal to these injection sites. B Intra-VTA SB microinjections increased demand elasticity (α) compared to dorsal control SB or VTA aCSF microinjections (n = 9). C None of the intraparenchymal microinjections impacted low-effort consumption (Q0). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Bar graphs represent means ± SEM.

Experiment 3: effects of intra-VTA SB infusions on cue-associated cocaine demand are not due to locomotor effects and do not occur for sucrose demand

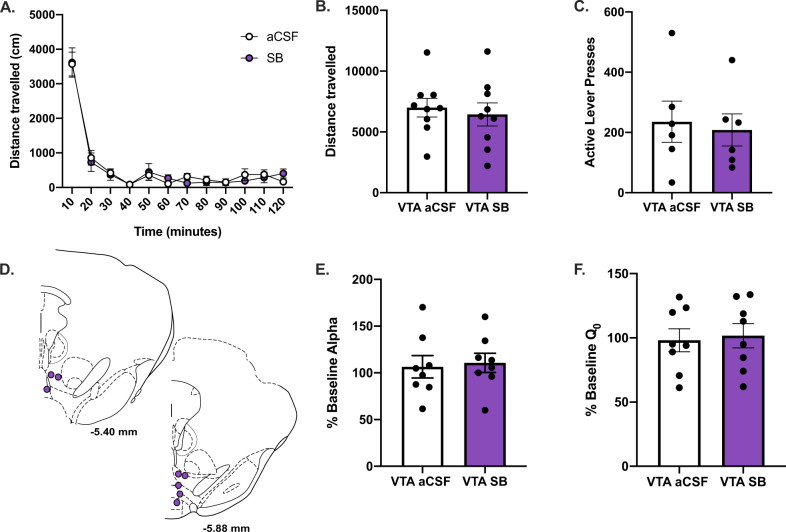

To confirm that intra-VTA effects were not due to deficits in locomotor ability or arousal, we microinjected SB or aCSF into VTA prior to locomotor testing or FR1 for sucrose pellets. There were no differences in locomotor activity between VTA aCSF and SB sessions when data were binned in 10-min intervals (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of time: F11,88 = 56.86, p < 0.0001, main effect of treatment: F1,8 = 0.02; p = 0.90, treatment × time interaction: F11,88 = 0.42, p = 0.95; Fig. 4A) or summed across the testing period (paired t-test: t8 = 0.39, p = 0.71; Fig. 4B). We also observed that SB did not affect the number of active lever presses for sucrose FR1 self-administration (paired t-test: t5 = 0.36, p = 0.73; Fig. 4C), indicating that intra-VTA SB did not impair lever pressing. These studies highlight that SB effects during cue-associated BE testing were not due to sedation or other nonspecific motor effects.

Fig. 4. SB did not have an impact on locomotor activity or motivation for natural (sucrose) reward.

A, B Locomotor activity following intra-VTA microinjection of SB. SB did not have an impact on locomotor activity in any of the 10-min testing bins (n = 9; A) or total locomotor activity (B). C Intra-VTA SB also did not have an impact on active lever presses for sucrose pellets on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement (n = 6). D–F Effects of intra-VTA SB (injection sites in D) on demand for sucrose in a BE test (n = 8). SB did not impact motivation (α; E) nor low-effort consumption (Q0; F) for sucrose pellets. Bar graphs indicate means ± SEMs.

We sought to determine whether SB effects on motivation were drug-specific and did not affect motivation for a natural reward, sucrose. We found that intra-VTA SB did not have an impact on motivation (α) (paired t-test: t7 = 0.25, p = 0.81; Fig. 4E) or low-effort consumption for sucrose (Q0) during sucrose BE with cues (paired t-test: t7 = 0.35, p = 0.73; Fig. 4F). These experiments confirmed that intra-VTA SB effects on motivation during cue-associated cocaine BE were specific to cocaine demand and not the consequence of changes in natural reward processing.

Experiment 4: knockdown of orexin input to VTA attenuated cue-enhanced motivation for cocaine

To interfere with the orexin-VTA circuit by an alternative method, we microinjected a retrogradely transported AAV (AAVretro, [26]) containing OxshRNA or control scRNA into VTA to selectively knock down orexin expression in neurons projecting to VTA (Fig. 5A). First, we confirmed that the AAVretro-OxshRNA specifically reduced orexin expression when injected into VTA. We observed a significant decrease in total orexin cell numbers in AAVretro-OxshRNA subjects compared to AAVretro-scRNA-infused animals (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of virus: F1,12 = 45.88, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5D) at 2 weeks (Sidak’s multiple comparisons test: p = 0.002), 4 weeks (p = 0.006), and 6 weeks (p = 0.02) post infusion. AAVretro-OxshRNA injection into VTA did not have an impact on the number of melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH)-expressing neurons in the same region of the hypothalamus at any time point (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of virus: F1,11 = 0.54, p = 0.48; Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. Retrograde knockdown of orexin in neurons projecting to VTA increased cocaine demand elasticity.

A Schematic of experiments using microinjection of the AAVretro-OxshRNA into VTA to knock down orexin in VTA-projecting neurons in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA). B Frontal sections through hypothalamus stained with an antibody for orexin A, indicating orexin knockdown in rats with AAVretro-OxshRNA microinjected into VTA, compared to control animals with AAVretro-scRNA microinjected into VTA. Midline is at the left, dorsal is upwards, scale bars indicate 100 µm. C–E Data from specificity validation experiments (1 µL of intra-VTA AAVretro-OxshRNA or AAVretro-scRNA virus infused unilaterally; n = 2–4/group). C Plots of microinjection locations in VTA in animals infused with the AAVretro-OxshRNA (green circles) or -scRNA viruses (black circles) for specificity validation experiments. There was a significant difference in orexin cell numbers at 2, 4, and 6 weeks post intra-VTA injection in AAVretro-OxshRNA animals, compared to rats with control (AAVretro-scRNA) injections into VTA (cells counted in both hemispheres; D). No changes were observed in the number of MCH-containing neurons in the same hypothalamic area for these same injections (E). F–L Data from behavioral experiments (0.3 µL of AAVretro-OxshRNA or AAVretro-scRNA virus infused intra-VTA bilaterally) in a different cohort of animals. F Plots of microinjection locations in VTA in animals infused with the AAVretro-OxshRNA (green circles) and -scRNA viruses (black circles) for behavioral experiments. G AAVretro-OxshRNA microinjected into VTA reduced the total bilateral number of orexin-immunoreactive neurons in animals tested on behavior, compared to AAVretro-scRNA animals (n = 7/group). H AAVretro-OxshRNA significantly reduced the number of orexin-expressing cells in LH compared to AAVretro-scRNA. Results were not significant for orexin cells in perifornical/dorsomedial hypothalamus (Pef/DMH). I Rats with AAVretro-OxshRNA microinjection into VTA exhibited increased α (reduced motivation) 5 weeks post injection. No differences were observed in AAVretro-scRNA animals. J–L AAVretro-OxshRNA did not have an impact on Q0 (J) or locomotor activity (K, L; n = 7–8/group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Bar graphs indicate means ± SEMs.

We then infused AAVretro-OxshRNA into VTA prior to BE testing with cues in a separate group of animals that were trained to self-administer cocaine with cues (Fig. 5F–L). Orexin expression was reduced by roughly 35% in AAVretro-OxshRNA compared to AAVretro-scRNA animals (unpaired t-test: t12 = 2.41, p = 0.03; Fig. 5G). The knockdown of orexin expression also was topographically specific: AAVretro-OxshRNA treatment was associated with a significant knockdown of orexin expression in the LH region (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of virus: F1,12 = 6.05, p = 0.03; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test: p = 0.044; Fig. 5H). Although there was a trend towards a reduction of orexin expression in Pef/DMH cells, this failed to reach significance (p = 0.10). Consistent with these results, we microinjected the retrograde tracer cholera toxin B (CTb) into VTA in a separate cohort of rats and observed that a greater percentage of LH orexin cells were retrogradely labeled than Pef/DMH orexin cells (paired t-test: t7 = 4.08, p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S2). These results show that orexin neurons in LH more often project to VTA than those in PeF/DMH, and that AAVretro-OxshRNA injected into VTA significantly decreased orexin expression in LH.

There was a main effect of time on α (two-way RM ANOVA: F1,12 = 7.21, p = 0.02; Fig. 5I) in OxshRNA-infused animals from baseline to week 5 (Sidak’s multiple comparisons test: p = 0.03), but no such effect on Q0 (two-way RM ANOVA: F1,12 = 2.97, p = 0.11; Fig. 5J). One animal given the scRNA virus was excluded from BE analyses as a behavioral outlier following treatment. When we included this animal in our analyses, it did not have an impact on the significance of our findings for α (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of time: F1, 13 = 8.73, p = 0.01; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test: OxshRNA: p = 0.04, scRNA: p = 0.32) or Q0 (two-way RM ANOVA, main effect of time: F1,13 = 3.54, p = 0.08, data not shown). We observed a significant main effect of time on habituated locomotor activity (two-way RM ANOVA: F11,143 = 20.92, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5K) and a trend towards a virus × time interaction (F11,143 = 1.83, p = 0.06) in binned data, but no effect of virus on total locomotor activity (unpaired t-test: t13 = 0.79, p = 0.45; Fig. 5L). Collectively, the results from these studies recapitulate our SB results, as retrograde knockdown of the orexin-VTA circuit reduced cue-associated cocaine motivation without impacting low-effort consumption or locomotor arousal.

Discussion

Here, we show that interference with orexin signaling in VTA, either through pharmacological or shRNA manipulations, reduced cue-associated motivation for cocaine. Intra-VTA SB significantly impacted motivation only when animals were trained and tested on BE with cues, and removing cues reduced the effect of intra-VTA SB on motivation. SB into VTA did not have an impact on Q0, general locomotor activity, or low-effort (FR1) responding for sucrose, indicating that SB effects on motivation were not due to sedation or simple motoric effects. In addition, intra-VTA SB did not have an impact on demand for sucrose, highlighting that effects on motivated cocaine taking were drug-specific and did not extend to motivation for natural rewards. Retrograde knockdown of orexin expression in VTA-projecting orexin cells reduced motivation during BE with cocaine-associated cues present. Collectively, these studies indicate that the orexin-VTA circuit is critically involved in the formation of drug-cue associations during intial drug taking, and that subsequent, highly motivated responding for cocaine requires the recruitment of this projection.

VTA Ox1R signaling was important for motivation only in animals trained to self-administer with cocaine-associated cues present

In animals given discrete cues paired with cocaine infusions during self-administration and BE training (Group 1), we observed that intra-VTA SB only reduced motivation (increased α) when cocaine-associated cues were present, and removing these cues reduced the efficacy of SB. In contrast, there was no effect of SB on BE performance with or without cues in animals trained on BE first without cues (Group 2), or trained to self-administer without cues (Group 3). Our results are consistent with a previous study from our lab showing that systemic SB reduced motivation only when animals were trained and tested with cues [5] and indicate that learning to associate discrete reward-paired cues with drug delivery may recruit the orexin system to drive motivation.

Orexins have been implicated in activating motivational drive in response to external stimuli associated with drug taking [1]. OxR1 signaling has been shown to be necessary for cue-dependent drug seeking. Blocking OxR1 signaling systemically or in VTA attenuated reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking induced by cues or contexts [11, 12, 27–29], a result that is largely consistent for other drugs of abuse and alcohol [30–33]. Fos expression of orexin neurons is also upregulated during cocaine-conditioned place preference and correlates with the degree of preference [34]. In contrast, orexin signaling seems to be less important for drug-seeking behaviors that are not induced by cues or contexts, such as drug-primed reinstatement [16]. Similarly, our prior study found that blocking Ox1R signaling does not attenuate self-administration or motivation for cocaine in the absence of conditioned cues [5], indicating that orexin does not mediate the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Rather, blocking orexin input to VTA seems to reduce the ability of conditioned cues to trigger motivation.

Removing cocaine-paired cues lowered motivation

We sought to determine how removing or adding cues impacted cocaine demand. To do this, we compared animals’ stable α and Q0 values in their first BE paradigm (cue BE for Group 1, no-cue BE for Groups 2 and 3) to their stable α and Q0 values in their second BE paradigm (cue BE for Group 2 and 3, no-cue BE for Group 1). Consistent with our previous study, we found that removing cues decreased motivation (increased α; Group 1). However, adding cues during BE did not alter motivation when animals were trained on FR1 and BE without cues (Group 3), or trained on FR1 with cues but trained on BE first without cues (Group 2). This is consistent with research that conditioned drug cues acquire motivational properties to stimulate drug taking [35], and that cues augment demand in both humans and rodents [5, 19, 36, 37]. These results also indicate that training on BE includes conditioning in addition to that obtained during FR1 training. These studies extend previous findings to show that cues are not sufficient to drive motivation in animals that are trained on the BE paradigm without cues, as cues did not augment motivation (decrease α) in Group 2 animals.

Intra-VTA SB only impacted cue-associated cocaine motivation when microinjected into VTA

To confirm that SB effects were specifically due to actions in VTA, we microinjected SB dorsal to VTA and observed no effects on motivation (Experiment 2). In the same animals, SB attenuated motivation (increased α) when microinjected into VTA, confirming the results of Experiment 1 in a separate cohort of animals. In addition, we observed no change in Q0 following VTA SB microinjections in the same animals, demonstrating that Ox1R signaling does not mediate low-effort consumption of cocaine. Other studies similarly showed that systemic SB does not affect FR1 responding for cocaine [9, 27]. These results are consistent with studies that demonstrated Ox1R signaling is necessary for high-effort drug taking [5, 8–10, 30, 31, 38, 39]. Finally, we observed no change in total or binned locomotor activity, or low-effort responding for sucrose, so SB did not alter motivation for cocaine by reducing locomotor arousal or ability. Our lab and others have similarly shown that systemic or local injections of SB into VTA did not interfere with locomotor activity [12, 27, 40]. Collectively, our study adds to a growing literature demonstrating that Ox1R signaling promotes high-effort drug taking through actions on VTA DA neurons.

Intra-VTA SB did not alter motivation for a natural reward

We found that intra-VTA SB microinjections did not have an impact on high- or low-effort consumption of sucrose during BE testing. Orexin has been linked to energy homeostasis and food consumption since its discovery [41, 42]. Orexin is preferentially recruited during feeding when motivation is high, as when animals are food-deprived or seeking palatable foods [40, 43, 44]. Previous studies have shown that orexin A modulates the hedonic value of highly palatable foods and promotes motivation to consume natural rewards [45–47]. Therefore, it is somewhat surprising that we did not observe changes in sucrose demand with intra-VTA microinjections. Importantly, animals were not food-restricted during our experiments, which has been shown to recruit the orexin system [48]. In addition, VTA may not be a critical site for orexin in motivated sucrose responding in ad libitum-fed animals. Intra-VTA microinjections of orexin A did not have an impact on breakpoint or total active lever presses during progressive ratio for sucrose in free-feeding animals [46] and other targets of orexin signaling may be more important for driving motivated sucrose taking [49–51]. Finally, as orexin A binds to both the orexin-1 and -2 receptors, the hedonic value of natural rewards may be mediated by the orexin-2 receptor; future studies are needed to investigate this possibility.

Knockdown of orexin input to VTA attenuated cue-associated motivation

To confirm that the orexin-VTA circuit mediates cue-augmented motivated responding for cocaine, we microinjected an AAVretro encoding an shRNA for orexin (OxshRNA) into VTA to knock down orexin expression in neurons that project to VTA. AAVretro-OxshRNA injection decreased the number of neurons expressing the orexin peptide by roughly 35% compared to control (AAVretro-scRNA) animals. In addition, AAVretro-OxshRNA injection reduced orexin cell number more in LH than in Pef/DMH. LH orexin neurons were also more likely to innervate VTA than PeF/DMH orexin neurons using CTb microinjections into VTA, consistent with the view that LH orexin neurons are important for motivation, a function linked closely to VTA [1, 16]. We also found that OxshRNA treatment reduced motivation for cocaine without impacting low-effort consumption. Consistent with our findings, previous studies reported that viral vector knockdown of Ox1R expression in VTA reduced motivation for cocaine on a progressive ratio schedule [52]. Similarly, local knockdown of orexin expression in hypothalamus lowered motivation for cocaine during BE [17, 18] or progressive ratio [25]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use viral vector manipulation of the orexin-VTA circuit during self-administration. Our study adds to a growing literature showing that the orexin-VTA circuit is important for motivated, cue-driven addiction behaviors.

Electron microscopy found that relatively few orexin fibers in VTA form monosynaptic connections onto DA or GABA neurons, so that most orexin input to VTA was hypothesized to come from en passant orexin fibers to caudal brainstem structures or from non-synaptic orexin varicosities [53]. Nonetheless, retrograde- and anterograde-labeling studies showed that a substantial proportion of orexin neurons project to VTA [54, 55]. Also, we and others have reported that orexin neurons influence the activity of VTA DA neurons via actions at glutamatergic terminals [14, 56]. Given the degree of orexin knockdown in our study, it is possible that the AAVretro uptake also occurred in orexin-containing passing fibers or varicosities, as well as in synaptic orexin terminals onto VTA neurons. However, a previous study found that AAVretro does not substantially label non-terminal passing fibers [57]. Orexin neurons have been shown to collateralize [58–60] and thus it is possible that our AAVretro approach to achieving knockdown of VTA-projecting orexin neurons also resulted in reduced orexin input to other reward-associated brain regions, contributing to the behavioral effects observed here. In addition, there is evidence that broad orexin knockdown in hypothalamus decreases pro-dynorphin levels [25], which may also have contributed to the observed effects. Although we cannot rule out these possibilities, our AAVretro manipulation produced almost identical effects on cocaine demand as blocking Ox1R signaling in VTA with local microinjections of SB. Therefore, we believe that the behavioral effects of the AAVretro are largely driven by a reduction of orexin input (via both synaptic and potentially paracrine signaling) specifically onto VTA neurons. Finally, although we did not measure food intake or body weight over the treatment period, a separate study showed that hypothalamic microinjectioins of an orexin shRNA construct that resulted in a larger knockdown of orexin neurons than that observed in our study did not have an impact on body weight, or food or water consumption across 5 weeks post infusion [25]. Thus, it is unlikely that AAVretro infusion attenuated motivation by impacting other homeostatic processes; however, it will be important for future studies to test this directly.

Collectively, these studies highlight the role of Ox1R signaling in the orexin-VTA circuit in drug-cue learning and cue-dependent motivation for cocaine. The orexin system is recruited to modulate VTA during the initial learning of the drug-cue association and drive motivation with re-exposure to these cues. As a result, therapies targeted to the orexin-VTA circuit have the potential to ameliorate cue-associated motivation in cocaine addiction.

Funding and disclosure

This research was supported by PHS grants F31DA042588 (CBP), K99DA045765 (MHJ), and R01DA006214 (GAJ). All authors have no disclosures to report.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Brooke Schmeichel and Christopher Richie for critical and valuable input on viral vector expression experiments.

Author contributions

CBP and GAJ designed the experiments. CBP, MHJ, SO, and NS performed the experiments, and acquired and analyzed experimental data. CBP, MHJ, and GAJ interpreted experimental data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41386-021-01173-5.

References

- 1.Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Smith RJ, James MH, Aston-Jones G. Motivational activation: a unifying hypothesis of orexin/hypocretin function. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1298–303. doi: 10.1038/nn.3810.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James MH, Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Aston-Jones G. A decade of orexin/hypocretin and addiction: where are we now? Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;33:247–81. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_57.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:186–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentzley BS, Jhou TC, Aston-Jones G. Economic demand predicts addiction-like behavior and therapeutic efficacy of oxytocin in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11822–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406324111.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G. Orexin-1 receptor signaling increases motivation for cocaine-associated cues. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;41:1149–56. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12866.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, et al. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, et al. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espana RA, Melchior JR, Roberts DC, Jones SR. Hypocretin 1/orexin A in the ventral tegmental area enhances dopamine responses to cocaine and promotes cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:415–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2048-8.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espana RA, Oleson EB, Locke JL, Brookshire BR, Roberts DC, Jones SR. The hypocretin-orexin system regulates cocaine self-administration via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:336–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07065.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein DL, Badve PS, Barson JR, Bass CE, Espana RA. Hypocretin receptor 1 knockdown in the ventral tegmental area attenuates mesolimbic dopamine signaling and reduces motivation for cocaine. Addict Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/adb.12553.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahler SV, Smith RJ, Aston-Jones G. Interactions between VTA orexin and glutamate in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;226:687–98. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2681-5.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James MH, Charnley JL, Levi EM, Jones E, Yeoh JW, Smith DW, et al. Orexin-1 receptor signalling within the ventral tegmental area, but not the paraventricular thalamus, is critical to regulating cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:684–90. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000423.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moorman DE, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin modulates response of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons to prefrontal activation: diurnal influences. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15585–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2871-10.2010.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baimel C, Borgland SL. Orexin signaling in the VTA gates morphine-induced synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7295–303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4385-14.2015.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baimel C, Bartlett SE, Chiou LC, Lawrence AJ, Muschamp JW, Patkar O, et al. Orexin/hypocretin role in reward: implications for opioid and other addictions. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:334–48. doi: 10.1111/bph.12639.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahler SV, Smith RJ, Moorman DE, Sartor GC, Aston-Jones G. Multiple roles for orexin/hypocretin in addiction. Prog Brain Res. 2012;198:79–121. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59489-1.00007-0.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James MH, Stopper CM, Zimmer BA, Koll NE, Bowrey HE, Aston-Jones G. Increased number and activity of a lateral subpopulation of hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin neurons underlies the expression of an addicted state in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:925–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantazis CB, James MH, Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G. The number of lateral hypothalamus orexin/hypocretin neurons contributes to individual differences in cocaine demand. Addict Biol. 2019:e12795. 10.1111/adb.12795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Johnson AR, Thibeault KC, Lopez AJ, Peck EG, Sands LP, Sanders CM, et al. Cues play a critical role in estrous cycle-dependent enhancement of cocaine reinforcement. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1189–97. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0320-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantazis CB, Aston-Jones G. Lateral septum inhibition reduces motivation for cocaine: Reversal by diazepam. Addict Biol. 2020;25:e12742. doi: 10.1111/adb.12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G. Inhibiting subthalamic nucleus decreases cocaine demand and relapse: therapeutic potential. Addict Biol. 2017;22:946–57. doi: 10.1111/adb.12380.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGlinchey EM, James MH, Mahler SV, Pantazis C, Aston-Jones G. Prelimbic to Accumbens Core Pathway Is Recruited in a Dopamine-Dependent Manner to Drive Cued Reinstatement of Cocaine Seeking. J Neurosci. 2016;36:8700–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1291-15.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cason AM, Aston-Jones G. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman LR, Bentzley BS, James MH, Aston-Jones G. Sex differences in demand for highly palatable foods: role of the orexin system. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24:54–63. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyaa040.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmeichel BE, Matzeu A, Koebel P, Vendruscolo LF, Schmeichel H, Shahryari R, et al. Knockdown of hypocretin attenuates extended access of cocaine self-administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2373–82. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0054-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tervo DG, Hwang BY, Viswanathan S, Gaj T, Lavzin M, Ritola KD, et al. A designer AAV variant permits efficient retrograde access to projection neurons. Neuron. 2016;92:372–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RJ, See RE, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin signaling at the orexin 1 receptor regulates cue-elicited cocaine-seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06844.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith RJ, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin is necessary for context-driven cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Blockade of hypocretin receptor-1 preferentially prevents cocaine seeking: comparison with natural reward seeking. Neuroreport. 2014;25:485–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter-Stransky KA, Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G. Individual differences in orexin-I receptor modulation of motivation for the opioid remifentanil. Addict Biol. 2017;22:303–17. doi: 10.1111/adb.12323.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moorman DE, James MH, Kilroy EA, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin-1 receptor antagonism reduces ethanol self-administration and reinstatement selectively in highly-motivated rats. Brain Res. 2017;1654:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.10.018.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadkhani A, Fragale JE, Pantazis CB, Bowrey HE, James MH, Aston-Jones G. Orexin-1 receptor signaling in ventral pallidum regulates motivation for the opioid Remifentanil. J Neurosci. 2019;39:9831–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0255-19.2019.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fragale JE, Pantazis CB, James MH, Aston-Jones G. The role of orexin-1 receptor signaling in demand for the opioid fentanyl. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1690–7. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, et al. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010;105:1599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acker J, MacKillop J. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for tobacco: a virtual reality study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1409–16. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts341.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodnik ZD, Bernstein DL, Prince CD, Espana RA. Hypocretin receptor 1 blockade preferentially reduces high effort responding for cocaine without promoting sleep. Behav Brain Res. 2015;291:377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.051.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopf FW. Recent perspectives on orexin/hypocretin promotion of addiction-related behaviors. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:108013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiskerke J, James MH, Aston-Jones G. The orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces motivation, but not inhibitory control, in a rat stop signal task. Brain Res. 2020;1731:146222. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:322–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barson JR. Orexin/hypocretin and dysregulated eating: promotion of foraging behavior. Brain Res. 2020;1731:145915. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehr JB, Mitchison D, Bowrey HE, James MH. Sleep dysregulation in binge eating disorder and “food addiction”: the orexin (hypocretin) system as a potential neurobiological link. Neuropsychopharmacology. 10.1038/s41386-021-01052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Castro DC, Terry RA, Berridge KC. Orexin in rostral hotspot of nucleus accumbens enhances sucrose ‘liking’ and intake but scopolamine in caudal shell shifts ‘liking’ toward ‘disgust’ and ‘fear’. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2101–11. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terrill SJ, Hyde KM, Kay KE, Greene HE, Maske CB, Knierim AE, et al. Ventral tegmental area orexin 1 receptors promote palatable food intake and oppose postingestive negative feedback. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;311:R592–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00097.2016.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, et al. Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11215–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6096-08.2009.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cason AM, Aston-Jones G. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2013;226:155–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2902-y.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kay K, Parise EM, Lilly N, Williams DL. Hindbrain orexin 1 receptors influence palatable food intake, operant responding for food, and food-conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2014;231:419–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3248-9.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi DL, Davis JF, Fitzgerald ME, Benoit SC. The role of orexin-A in food motivation, reward-based feeding behavior and food-induced neuronal activation in rats. Neuroscience. 2010;167:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thorpe AJ, Cleary JP, Levine AS, Kotz CM. Centrally administered orexin A increases motivation for sweet pellets in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0040-5.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernstein DL, Badve PS, Barson JR, Bass CE, Espana RA. Hypocretin receptor 1 knockdown in the ventral tegmental area attenuates mesolimbic dopamine signaling and reduces motivation for cocaine. Addict Biol. 2018;23:1032–45. doi: 10.1111/adb.12553.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balcita-Pedicino JJ, Sesack SR. Orexin axons in the rat ventral tegmental area synapse infrequently onto dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:668–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.21420.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalez JA, Jensen LT, Fugger L, Burdakov D. Convergent inputs from electrically and topographically distinct orexin cells to locus coeruleus and ventral tegmental area. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1426–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08057.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fadel J, Deutch AY. Anatomical substrates of orexin-dopamine interactions: lateral hypothalamic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2002;111:379–87. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borgland SL, Storm E, Bonci A. Orexin B/hypocretin 2 increases glutamatergic transmission to ventral tegmental area neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06397.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z, Maunze B, Wang Y, Tsoulfas P, Blackmore MG. Global connectivity and function of descending spinal input revealed by 3D microscopy and retrograde transduction. J Neurosci. 2018;38:10566–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1196-18.2018.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ciriello J, McMurray JC, Babic T, de Oliveira CV. Collateral axonal projections from hypothalamic hypocretin neurons to cardiovascular sites in nucleus ambiguus and nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res. 2003;991:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.016.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee EY, Lee HS. Dual projections of single orexin- or CART-immunoreactive, lateral hypothalamic neurons to the paraventricular thalamic nucleus and nucleus accumbens shell in the rat: Light microscopic study. Brain Res. 2016;1634:104–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.062.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Espana RA, Reis KM, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW. Organization of hypocretin/orexin efferents to locus coeruleus and basal forebrain arousal-related structures. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:160–78. doi: 10.1002/cne.20369.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.