Abstract

About 2.5 years after the first isolation of the VanA phenotype of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREM) in Poland, the first VREM strains with the VanB phenotype have emerged independently in two different Warsaw hospitals. In one of these the VREM strain was selected during the long-term antimicrobial treatment of a patient with a wide variety of infection risk factors who died after 3 months of hospitalization. The strain was found to contain the transferable vanB2 gene cluster variant of the polymorphic type that was identified earlier in vancomycin-resistant enterococci from several different countries. In the course of infection the strain underwent genetic diversification due to DNA recombination.

CASE REPORT

In the middle of June 1999, a 68-year-old woman with acute pancreatitis was subjected to surgical evacuation of necrotic tissues and extraperitoneal drainage in a Warsaw hospital. Having developed septic shock, she was transferred from the surgical ward to the intensive care unit (ICU). Various risk factors for infection were identified in the patient, and these included obesity, diabetes, adult respiratory distress syndrome, intubation, tracheostomy, ventilation, gastric tube, intravenous central catheter, total parenteral nutrition, continuous extraperitoneal lavage, urinary catheter, prolonged hospitalization, and intensive antibiotic therapy. The following antimicrobials were used for the treatment in the ICU: metronidazole, cefoperazone, imipenem, vancomycin, amikacin, piperacillin with tazobactam, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, co-trimoxazole, and fluconazole. Several different pathogens were recovered from the patient during this period including a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain that produced an extended-spectrum β-lactamase, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain resistant to imipenem, a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain, a vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium strain, and a vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (VREM) isolate. Vancomycin was introduced into therapy on the 12th day of hospitalization, after the first isolation of MRSA, and was used in three therapeutic courses of at least 15 days each. The first VREM isolate was cultured from a skin lesion at the end of August 1999, after 52 days (in total) of vancomycin therapy. The patient died after 90 days of hospitalization with symptoms of generalized infection and multiorgan failure.

Altogether four VREM isolates were collected during the treatment (Table 1); three were identified in clinical samples from the patient (skin lesion, peritoneum, and stool), and one was identified from the patient's environment (the patient's bedsheet). No vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) were recovered during the testing of other patients, medical personnel, and the entire ICU environment that was performed immediately after isolation of the first VREM isolate. In order to prevent strain dissemination, the patient was isolated with dedicated medical personnel, and advanced infection control procedures were introduced into the ward according to the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (11). The preventive action was successful, as no VRE have been isolated in the hospital since that time.

TABLE 1.

Selected clinical data for the clinical isolates and PFGE typing, mating, and vanB gene sequence and polymorphism results

| Isolate | Date of isolation (day.mo.yr) | Source | Mating | PFGE type | vanB gene cluster polymorphisma | vanB gene sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecium 8533 | 31.08.99 | Skin lesion | + | a1 | RFLP-2 | NDb |

| E. faecium 8647 | 09.09.99 | Environment | + | a1 | RFLP-2 | ND |

| E. faecium 8672 | 15.09.99 | Peritoneum | − | a2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 |

| E. faecium 8673 | 15.09.99 | Stool | + | a1 | RFLP-2 | ND |

| E. faecalis V583c | RFLP-1d | vanB1e |

Microbiology.

The VREM isolates were subjected to detailed microbiological and epidemiological analyses. Genus identification was performed as described by Facklam and Collins (9), and the species was identified by the API Rapid ID32 STREP test (bioMérieux, Charbonnieres-les-Bains, France), supplemented by potassium tellurite reduction, motility, and pigment production tests (9). The MICs of different antimicrobial agents were evaluated by the agar dilution method according to NCCLS guidelines (17) and by the Etest in the case of quinupristin-dalfopristin and linezolid (the linezolid susceptibility data were interpreted according to the manufacturer's recommendations). Antimicrobial standards were supplied by the corresponding manufacturers. Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, S. aureus ATCC 29213, and E. faecalis V583, the standard VanB phenotype strain (8, 22), were used as reference strains. The isolates were characterized by the high level of resistance to vancomycin (MICs, 128 to 256 μg/ml) and susceptibility to teicoplanin (MICs, 0.25 to 1 μg/ml), which suggested the VanB phenotype of vancomycin resistance. Additionally, they were resistant to penicillin (MICs, 128 μg/ml), ampicillin (MICs, 64 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (MICs, 16 to 64 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (MICs, 32 μg/ml) and also to high concentrations of aminoglycosides (gentamicin MICs, >1,024 μg/ml; streptomycin MICs, >2,048 μg/ml). The only antimicrobials to which the isolates were susceptible were tetracycline (MICs, 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml), quinupristin-dalfopristin (MICs, 0.5 μg/ml), and linezolid (MICs, 1 μg/ml). The susceptibility testing revealed the multidrug resistance phenotype of the VREM isolates.

The vancomycin resistance transfer experiment was carried out with the isolates by the filter-mating procedure described by Klare et al. (15). E. faecium 64/3, which is resistant to rifampin and fusidic acid (28), was used as a recipient. The results are listed in Table 1. All but one isolate (isolate 8672) produced transconjugants at an efficiency of about 10−5 per donor cell, which indicated that the vancomycin resistance determinants were transferable and had a relatively high transmission potential. Evaluation of the MICs for the recombinant strains revealed that resistance to no other drug was cotransferred with the resistance to vancomycin (data not shown).

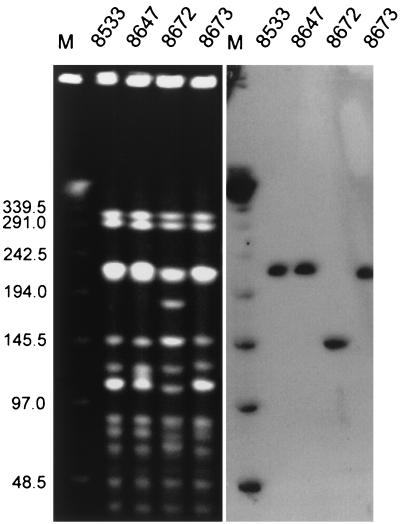

Clinical isolates were typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) with a CHEF DRII system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). DNA purification and digestion with the SmaI restriction enzyme (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) were performed as described by Clark et al. (5), and the electrophoresis was run under the conditions described by de Lencastre et al. (7). PFGE results were interpreted by the criteria proposed by Tenover et al. (26). The results are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. All isolates were found to represent a single PFGE type; however, one of these, isolate 8672, produced PFGE pattern a2, which differed by five DNA bands from the pattern for the predominant one, PFGE pattern a1. These data suggested that the patient was originally infected with a single VREM strain which underwent some genetic differentiation with time.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of VREM isolates and location of the vanB gene cluster within the PFGE patterns. Total DNA of the isolates was cut with SmaI and separated by PFGE and was hybridized with the vanB gene cluster probe. Lanes M, bacteriophage λ ladder molecular size standard (in kilobases; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.).

For the identification of vancomycin resistance genes, the total DNAs of the isolates were purified with the Genomic DNA Prep Plus kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdańsk, Poland). The vanB gene was detected by specific PCR with two different pairs of primers, the vanB and vanB consensus primers, and the cycling conditions used were those described originally (5, 6). For all the isolates the PCR with the vanB primers, which are specific for the vanB1 gene variant (5, 6), amplified products of about 1.1 kb instead of 433 bp, as predicted for vanB1 and obtained for the vanB1-containing V583 E. faecalis control strain (8, 21, 22). The vanB consensus primers, which amplify specific products from all vanB gene variants known to date (6), produced amplicons of about 500 bp, which corresponded well with the expected size of 484 bp. These data confirmed that the isolates were of the VanB phenotype and revealed that this phenotype was determined by a gene cluster variant which was different from vanB1.

The vanB gene-containing 1.1-kb PCR product obtained for isolate 8672 was subjected to direct DNA sequencing. Sequencing reactions (24) were performed with the use of primers vanB (5) supplemented by internal primers 5′-GACAAATCACTGGCC-3′ and 5′-ATGGCTTCTTGCATAGC-3′ and an ABI 310 PRISM automatic system (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). It was found that the PCR product encompassed the 896-bp fragment of the vanB coding region starting from its 5′ end (out of 1,029 bp altogether) and the 201-bp fragment of the vanHB reading frame that is located directly upstream of vanB (with an overlap of 8 bp). This indicated that, similarly to known vanB2 and vanB3 variants (10, 18), the 5′ primer of the vanB primer pair (5) did not anneal to the vanB coding region; however, it must have been complementary to a sequence present within the vanHB gene, which seems to be unique (6). The vanB gene sequence was found to be identical to the corresponding part of one of vanB2 variants identified previously in Rochester, Minn. (GenBank accession no. U94526) (18) and differed by a single base pair from a vanB2 gene sequenced in Taiwan (GenBank accession no. Z83305).

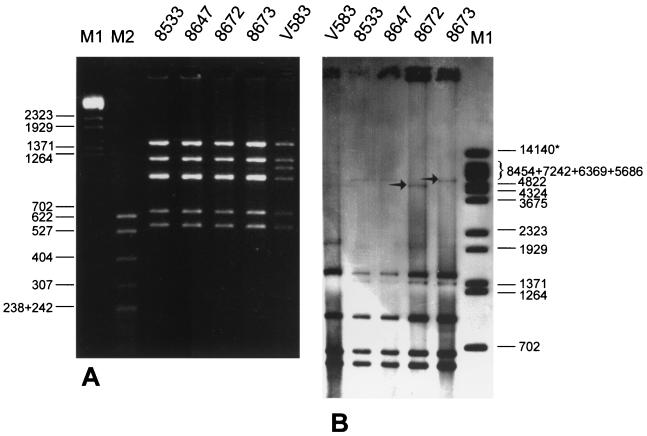

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the vanB2 gene cluster was studied as proposed by Dahl et al. (6). DNA fragments encompassing the vanRB, vanSB, vanYB, vanW, vanHB, vanB, and vanXB genes were amplified by long PCR (L-PCR) with the use of primer vanB long, and the resulting L-PCR products were analyzed with the use of the DraI and PagI (an isoschizomer of BspHI) restriction enzymes (MBI Fermentas). The results are shown in Fig. 2A and Table 1. L-PCR products of the expected size of about 6 kb were obtained for all isolates analyzed. The amplified regions were found to represent a single polymorph, which was originally identified as RFLP-2 in vanB2 and vanB3 gene clusters from E. faecium and E. faecalis isolates collected in Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States (6).

FIG. 2.

RFLP analysis of vanB gene clusters in VREM isolates. (A) DraI-PagI restriction analysis of vanB gene clusters amplified by L-PCR. Lanes M1, BstEII-digested bacteriophage λ molecular size standard (in base pairs); lane M2, MspI-digested pBR322 molecular size standards (in base pairs; T. E. Kucharczyk, Warsaw, Poland). (B) DraI-PagI RFLP analysis of vanB loci analyzed by hybridization of total DNA with the vanB gene cluster probe. The arrows indicate DNA bands that distinguished the two polymorphs of the region. The asterisk indicates the DNA band of the BstEII-digested bacteriophage λ molecular size marker (in base pairs), which results from the sticking of the 8,454-bp fragment to the 5,686-bp fragment by the cos ends.

In order to study the location of the vanB2 gene cluster, the total DNAs of the isolates, embedded in agarose plugs and digested with SmaI, were separated by PFGE (as described above), blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), and hybridized with the vanB gene cluster probe. The L-PCR amplicon of the vanB1 gene cluster present in the E. faecalis V583 VanB reference strain (8, 21, 22) was used as the probe. Probe labeling, hybridization, and signal detection were performed with the ECL Random-Prime Labeling and Detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Results of the analysis are shown in Fig. 1. Single hybridizing DNA bands were revealed for each isolate, and in the case of the three PFGE subtype a1 isolates, the vanB2 gene cluster was located within the SmaI restriction fragment of about 230 kb, whereas in PFGE subtype a2 isolate 8672, this fragment was about 150 kb. It is likely that the vanB2 gene cluster resided within a transposon (4, 20) which was inserted into chromosomal DNA or a particularly large plasmid and which may have possessed conjugative functions itself (4, 19, 20). Its horizontal transfer may also have been mediated by plasmid conjugation (3, 29) or by another transferable mobile element (4, 19). A rearrangement of chromosomal or plasmid DNA, reflected by the change in the PFGE pattern, has affected the position of the vanB2 gene cluster DNA within the PFGE pattern of isolate 8672 and might have been responsible for the loss of its transferability.

For a more detailed analysis of the vanB2 locus, the total DNAs of the isolates, purified with the Genomic DNA Prep Plus kit (A&A Biotechnology), were digested with the DraI and PagI restriction enzymes (MBI Fermentas), electrophoresed, blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane, and hybridized with the vanB gene cluster probe. Probe labeling and hybridization were performed as described above. The results are shown in Fig. 2B. The hybridization patterns obtained corresponded well to the DraI-PagI (BspHI) RFLP patterns of the isolated vanB2 gene clusters, and the only difference observed among the isolates was that the largest DNA fragment of the patterns was smaller for PFGE subtype a2 isolate 8672 (ca. 4.8 kb) than for the remaining isolates (ca. 5.5 kb). These data suggested that the DNA recombination event(s) that occurred in isolate 8672 has changed the structure of either the vanB2 gene cluster-containing transposon or its directly adjacent sequence context.

VRE belong to the most dangerous nosocomial pathogens that usually cause infections in severely debilitated patients hospitalized for long periods of time. The first strains of VRE were identified in 1986 in France (16) and in the United Kingdom (27), and since then these microorganisms have become common in many countries all over the world (2, 5, 25). Until recently, they were not observed in Poland (13, 30); however, in last few years VRE have started to emerge in different hospitals in Poland. The first reported incidence occurred in December 1996 in a hospital in Gdańsk (12) with the identification of VREM of the VanA phenotype (1). This isolation was followed by a large and complicated outbreak in two different hematological wards of the center (14, 23).

Data presented in this work document one of the first two incidences of a VREM strain expressing the VanB phenotype (8, 21, 22) in Poland. The strain was isolated from a single patient located in the ICU of a Warsaw hospital who was particularly prone to nosocomial infection. Due to immediate introduction of strict infection control procedures (11), the VREM strain was most likely eradicated from the hospital environment. The detailed molecular analysis revealed that its phenotype was determined by the vanB2 gene cluster variant, which resided within a transferable DNA molecule. During the infection process the strain underwent genetic diversification due to a DNA rearrangement that also affected the vanB locus. The VanB phenotype was originally reported by Sahm et al. (22) in 1989 and was described by Quintiliani et al. (21) in 1993, and since then it has spread in several countries (6). It is determined by a cluster of genes located within composite transposons that may be horizontally transmitted between strains either by themselves or by a plasmid-mediated or other conjugative element-mediated process (3, 4, 19, 20, 29). Several works carried out with VanB strains of VRE from different countries (6, 8, 10, 18) revealed a certain degree of heterogeneity of the vanB gene sequence (vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 variants) and of RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster (RFLP-1, -2, and -2*). Identification of the next case of infection with the vanB2 variant present in the context of the RFLP-2 polymorph of the gene cluster confirms the earlier observation of the high degree of stability of the vanB-region sequences and the hypothesis that they have a common evolutionary origin (6).

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Murchan for critical reading of the manuscript; Patrice Courvalin, who kindly provided E. faecalis V583; and Wolfgang Witte for strain E. faecium 64/3.

This work was partially financed by a grant from the Polish Committee for Scientific Research (grant KBN 4P05A 016 19) and by the U.S.-Poland Maria Sklodowska-Curie Joint Found II (grant MZ/NIH-98-324).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J M, Paton J C, Turnidge J. Emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Australia: phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2187–2190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2187-2190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce J M, Opal S M, Chow J W, Zervos M J, Potter-Bynoe G, Sherman C B, Romulo R L C, Fortna S, Medeiros A A. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium with transferable vanB class vancomycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1148-1153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carias L L, Rudin S D, Donskey C J, Rice L B. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4426–4434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4426-4434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark N, Cooksey R, Hill B, Swenson J, Tenover F. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahl K H, Skov Simonsen G, Olsvik Ø, Sundsfjord A. Heterogeneity in vanB gene cluster of genetically diverse clinical strains of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lencastre H, Severina E P, Roberts R B, Kreiswirth B N, Tomasz A. Testing the efficacy of a molecular surveillance network: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) genotypes in six hospitals in the metropolitan New York City area. The BARG Initiative Pilot Study Group. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance Group. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:343–351. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evers S, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. Sequence of the vanB and ddl genes encoding d-alanine:d-lactate and d-alanine:d-alanine ligases in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583. Gene. 1994;140:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facklam R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold H S, Ünal S, Cercenado E, Thauvin-Eliopulos C, Eliopulos G M, Wennerstein C B, Moellering R C., Jr A gene conferring resistance to vancomycin but not teicoplanin in isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium demonstrates homology with vanB, vanA, and vanC genes of enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1604–1609. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Recommendations for preventing the spread of vancomycin resistance: recommendations of the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) Am J Infect Control. 1995;23:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(95)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hryniewicz W, Szczypa K, Bronk M, Samet A, Hellmann A, Trzciński K. First report of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated in Poland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:503–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hryniewicz W, Zaręba T, Kawalec M. Susceptibility patterns of Enterococcus spp. isolated in Poland during 1996. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1998;10:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawalec M, Gniadkowski M, Hryniewicz W. Outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in a hospital in Gdańsk, Poland, due to horizontal transfer of different Tn1546-like transposon variants and clonal spread of several strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3317–3322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3317-3322.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klare I, Collatz E, Al.-Obeid S, Wagner J, Rodloff A C, Witte W. Glykopeptidresistenz bei Enterococcus faecium aus Besiedlungen und Infectionen von Patienten aus Intensivstationen Berliner Kliniken und einem Transplantationszentrum. ZAC Z Antimikrob Antineoplast Chemother. 1992;10:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; M7–A5. 5th ed. 20, no. 2. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel R, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Steckelberg J M, Kline B, Cockerill F R., III DNA sequence variation within vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2/3 genes of clinical Enterococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:202–205. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Conjugal transfer of the vancomycin-resistance determinant vanB between enterococci involves the movement of large genetic elements from chromosome to chromosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:359–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1547, composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene. 1996;172:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintiliani R, Jr, Evers S, Courvalin P. The vanB gene confers various levels of self-transferable resistance to vancomycin in enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1220–1223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahm D F, Kissinger J, Gilmore M S, Murray P R, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samet A, Bronk M, Hellmann A, Kur J. Isolation and epidemiological study of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from patients of a haematological unit in Poland. J Hosp Infect. 1999;41:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suppola J P, Kolho E, Salmenlinna S, Tarkka E, Vuopio-Varkila J, Vaara M. vanA and vanB incorporate into an endemic ampicillin-resistant vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus faecium strain: effect on interpretation of clonality. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3934–3939. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3934-3939.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Goering V, Mickelsen P, Murray B M, Pershing D, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uttley A H C, George R C, Naidoo J, Woodford N, Johnson A P, Collins C H, Morrison D, Gilfillan A J, Fitch L E, Heptonstall J. High-level vancomycin-resistant enterococci causing hospital infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:173–181. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werner G, Klare I, Witte W. Arrangement of the vanA gene cluster in enterococci of different ecological origin. FEMS Microb Lett. 1997;155:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodford N, Jones B L, Baccus Z, Ludlam H A, Brown D F J. Linkage of vancomycin and high-level gentamicin resistance genes on the same plasmid in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:179–184. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaręba T, Hryniewicz W. Patterns of antibiotic resistance among enterococcal strains isolated from clinical specimens and food in Poland. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:69–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02112626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]