Abstract

Age-related hearing loss, or presbyacusis, is a prominent chronic degenerative disorder that affects many older people. Based on presbyacusis pathology, the degeneration occurs in both sensory and non-sensory cells, along with changes in the cochlear microenvironment. The progression of age-related neurodegenerative diseases is associated with an altered microenvironment that reflects chronic inflammatory signaling. Under these conditions, resident and recruited immune cells, such as microglia/macrophages, have aberrant activity that contributes to chronic neuroinflammation and neural cell degeneration. Recently, researchers identified and characterized macrophages in human cochleae (including those from older donors). Along with the age-related changes in cochlear macrophages in animal models, these studies revealed that macrophages, an underappreciated group of immune cells, may play a critical role in maintaining the functional integrity of the cochlea. Although several studies deciphered the molecular mechanisms that regulate microglia/macrophage dysfunction in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, limited studies have assessed the mechanisms underlying macrophage dysfunction in aged cochleae. In this review, we highlight the age-related changes in cochlear macrophage activities in mouse and human temporal bones. We focus on how complement dysregulation and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome could affect macrophage activity in the aged peripheral auditory system. By understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie these regulatory systems, we may uncover therapeutic strategies to treat presbyacusis and other forms of sensorineural hearing loss.

Keywords: Presbyacusis, Macrophages, Stria vascularis, Auditory nerve, Complement system, NLRP3 inflammasome

INTRODUCTION

Presbyacusis is a chronic multidimensional disorder that affects approximately 50% of people who are 75 years and older in the USA. This number is expected to grow as the population continues to age (National Academy of Science, 2016). Presbyacusis is defined by reduced hearing sensitivity and speech comprehension, especially in noisy environments, which diminishes central processing of acoustic information (Gates and Mills, 2005). Although hearing loss affects each person differently, adults experiencing hearing loss often report symptoms such as isolation, social withdrawal, fatigue, and depression (Kaland and Salvatore, 2002). In the past seven decades, characterization of presbyacusis pathophysiology has demonstrated that degeneration and dysfunction of multiple cochlear cell types are associated with the onset and/or progression of declines in auditory function. These cell types include sensory hair cells of the organ of Corti, spiral ganglion neurons and myelinating glial cells of the peripheral auditory nerve (AN), and non-sensory cells in the stria vascularis and spiral ligament of the cochlear lateral wall (Gratton et al. 1996; Gratton et al. 1997; Spicer et al. 1997; Spicer and Schulte 2002; Merchant 2010; Schuknecht and Gacek 1993; Schuknecht 1955, 1964; Fleischer 1972; Saitoh et al. 1995; Sha et al. 2008; Hao et al. 2014; Hequembourg and Liberman 2001; Kidd Iii and Bao 2012; Kusunoki et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2019a, 2019b; Makary et al. 2011; Ohlemiller et al. 2008; Shi 2016; Wu et al. 2020; Hilding 1953; Xing et al. 2012; Eckert et al. 2020). Although multiple factors and pathways contribute to presbyacusis, we do not fully understand the main causes of the condition.

Inflammaging refers to chronic and low-grade inflammation of tissues and/or organs. This common form of immune dysfunction occurs increasingly with age (Franceschi and Campisi 2014). Dysregulation of the immune response and inflammation (such as inflammaging) play critical roles in age-related neurodegenerative disorders (Verschuur et al. 2014; Watson et al. 2017). Macrophages are a key part of the innate immune system that have important roles in inflammaging and cochlear tissue degeneration in presbyacusis (Watson et al. 2017; Keithley 2019). In animal models, macrophages are present in several areas of the adult cochlea, including the organ of Corti (Frye et al. 2017), the AN (within the osseous spiral lamina, Rosenthal’s canal and modiolus) (Kaur et al. 2015, 2018; Lang et al. 2016; Brown et al. 2017; Panganiban et al. 2018), and the spiral ligament of the cochlear lateral wall (Hirose et al. 2005; Tornabene et al. 2006). Macrophages also closely interact with the strial microvasculature, a major part of the blood-labyrinth barrier that governs cochlear homeostasis. These innate immune cells direct the immune response as part of the neurovascular unit (Shi 2016; Neng et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). The interactions of macrophages with other non-sensory cells in the stria regulate permeability of the blood-labyrinth barrier. This relationship is highly sensitive to injury, such as noise exposure that changes macrophage numbers, morphology, and activation states (see reviews by Shi 2016; Presta et al. 2018). Macrophage activation and changes in the innate immune system can lead to chronic inflammation that contributes to age-related changes in the cochlear microenvironment. This process plays a central role in degeneration and dysfunction of cochlear cells in presbyacusis.

Several reviews comprehensively described the macrophage-associated inflammatory response and inflammation in sensorineural hearing loss (Hirose et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2017; Kalinec et al. 2017; Wood and Zuo 2017; Watson et al. 2017; Frye et al. 2019; Warchol 2019). In this review, we focus on changes in cochlear macrophage activities in mouse models of age-related hearing loss and human cochleae obtained from older donors. We will discuss two key molecular mechanisms that regulate the innate immune response and macrophage activity: the complement system and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. Both mechanisms are involved in various age-related neurogenerative disorders, such as age-related macular degeneration (Gao et al. 2015), cardiovascular disease (North and Sinclair 2012), and Alzheimer’s disease (Halle et al. 2008).. Thus, these mechanisms could be targeted to create therapies that prevent or slow disease progression. This review focuses on how complement dysregulation and the NLRP3 inflammasome may contribute to changes in macrophage activity and the loss or dysfunction of cochlear cells in presbyacusis.

IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF MACROPHAGES IN HUMAN COCHLEA

Although early studies of human temporal bone found resident macrophages in the endolymphatic sac (Altermatt et al. 1990; Rask-Anderson et al. 1991), around the vestibular dark cell region (Masuda et al. 1997), and in the middle ear mucosa (Lim 1976), it has been thought that the human cochlea is immune-privileged. At least two subtypes of the cochlear macrophages are present in embryonic cochlea of mice (Kishimoto et al. 2019): one that depends on Csf1r and originates from the yolk sac, and another that does not depend on Csf1r and originates from the fetal liver via the systemic blood circulation. Researchers have used several well-established animal models, during development and in response to cochlear injury, to identify and characterize macrophage/microglial cells in multiple regions of the cochlea. These studies have deepened our understanding of how these innate immune cells affect the development and maintenance of cochlear cells, and repair/regeneration after cochlear injury (Fredelius et al. 1990; Bhave et al. 1998; Sekiya et al. 2001; Hirose et al. 2005; Frye et al. 2017; Kishimoto et al. 2019; Kaur et al. 2015, 2018; Brown et al. 2017; Panganiban et al. 2018; Noble et al. 2019; Warchol 2019). To translate macrophage studies in animal models and develop therapeutic targets and diagnostic tools for people with presbyacusis, we must integrate studies of human and animal cochlear tissues.

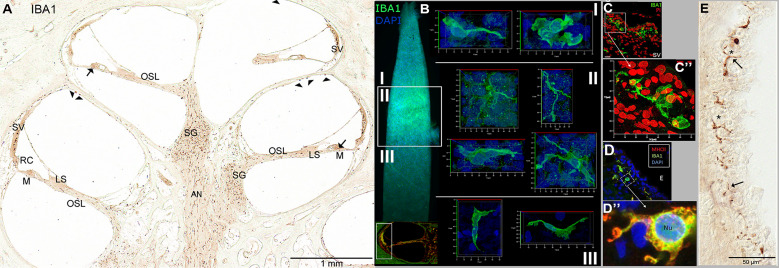

Human and rodent macrophages/microglia share common proteins, including ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1). In humans, IBA1 is encoded by the allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF1) gene (Autieri et al. 1996). IBA1+ macrophages were found throughout the peripheral AN within the osseous spiral lamina and modiolus, and in Rosenthal’s canal of the human temporal bones (Fig. 1 (a); O’Malley et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2019b; Noble et al. 2019). IBA1-expressing cells were present in the outer sulcus and root cells of the cochlear lateral wall, adjacent to perivascular cells within the intermediate cell layer of the stria vascularis, and in the spiral ligament (Fig. 1 (b–d); O’Malley et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2019b; Noble et al. 2019). In the organ of Corti, IBA1+ macrophages were located below Hensen cells (O`Malley et al. 2016).

Fig. 1.

Location of macrophages in multiple areas of adult human cochlea. (a) IBA1+ macrophages are present in the auditory nerve (the eighth nerve; AN) within the osseous spiral lamina (OSL) and modiolus, and within the spiral ganglion (SG). IBA1-expressing cells are also located in the organ of Corti (arrows), within the stria vascularis (SV) and the outer sulcus and root cell (RC) regions, below the basilar membrane (M), and in the scala vestibuli on the surface of the bone (arrowheads). Images in (a) and (e) were modified from O’Malley et al. 2016. (b) IBA1+ cells are present in the SV and spiral ligament of the cochlear lateral wall in a whole-mount preparation. The images of a single macrophage on the right were taken from the suprastrial (I), strial (II), and substrial (III) regions. (c, c″) A super-resolution image of a macrophage within the SV showing a three-dimensional version of macrophages with ramified processes in the strial region. Images in (b, c, c″) were modified from Noble et al. 2019. The image in c″ is the enlarged image of the boxed area in c. (d, d”) An IBA+ macrophage within the SV was stained for major histocompatibility complex class type II (MHCII). The image in d″ is the enlarged image of the boxed area in d. Nu, nucleus. Images in (d, d″) were modified from Liu et al. (2019a, 2019b). CD68+ (e) macrophages in the SV within the intermediate cell layer (*) show ramified processes (arrows). The specimen in (b, c, c″) was obtained from a 57-year-old donor. Specimens in (a, e) were from donors ranging from 52 to 88 years old. Specimens in (d, d″) were from donors aged 40 to 70 years. BV blood vessel

In addition to IBA1, other macrophage/microglial markers have been used successfully in human temporal bone, including cluster of differentiation 163 (CD163), CD68, and major histocompatibility complex class type II (MCHII) (Fig. 1 (d–f); O’Malley et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2019b; Noble et al. 2019). CD163 is a transmembrane protein, and scavenger receptor expressed in the monocytic lineage, including monocytes, macrophages, and microglia (Lau et al. 2004). CD163 is a widely accepted marker for microglia with an activated state (Jurga et al. 2020). Similar to IBA1, CD163-expressing cells were found in several cochlear regions, such as in the SV (Fig. 1 (e)) and spiral ligament of the cochlear lateral wall, in the organ of Corti, along the AN within the modiolus, and around and within the spiral ganglia, endolymphatic duct, and several other cochlear regions (O’Malley et al. 2016). CD68 is a general microglial marker and is significantly upregulated in monocyte lineage cells during inflammation (Holness et al. 1993; Jurga et al. 2020). Similar to IBA1 and CD163, cells expressing CD68 are present in human cochlea; however, CD68 was not present fully in the cytoplasm, as seen with anti-IBA and anti-CD183 antibodies. In fact, CD68 can be difficult to identify because of its punctate pattern with immunostaining (Fig. 1 (e)). These results support previous work by Holness and Simmons (1993) in which immunoreactivity for CD68 was often found in cytoplasmic granules and that CD68 localizes mainly to lysosomes and endosomes of activated macrophages. MHCII, another activated state marker, mobilizes immune cells in pathological conditions (Lebedeva et al. 2005). Interestingly, many IBA1-expressing cells also express MHCII in the SV and spiral ganglion of human temporal bones (Fig. 1 (d, d″)) (Liu et al. 2019b).

The studies that found abundant cells expressing well-established macrophage/microglia markers (i.e., IBA1, CD68, CD163, and MHCII) in multiple cochlear locations were conducted mostly in human temporal bones with no known otologic pathology. These data suggest that the human ear does not have a completely “immune-privileged” site, and that macrophages may regulate cochlear physiology and pathophysiology in humans.

AGE-RELATED CHANGES IN MACROPHAGES/MICROGLIA OF MOUSE AND HUMAN COCHLEA

Macrophage/microglia maintains and restores tissue homeostasis and integrity by surveying the microenvironment and recognizing debris or pathogens (Aloisi 2001). Macrophages/microglia are phenotypically heterogeneous in other nervous systems (Olah et al. 2011; Tan et al. 2020). For example, two cellular forms of microglia were found in brain tissues (Davis et al. 1994). The activated state and function of microglia could be determined by their distinct morphology, gene expression pattern, and the production of pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cytokines (Stence et al. 2001; Leone et al. 2006). Under physiological conditions, “resting” (or “ramified”) microglia are in a surveillance mode that allows them to sense the “well-being” of surrounding cells. In this mode, microglia are uniformly distributed with a highly branched morphology (e.g., multiple long branching processes and a small cellular body). Ramified macrophages/microglia perform limited phagocytosis and produce few immune molecules. With pathological conditions such as injury, activated microglia/macrophages have an amoeboid shape with no or only a few extended cellular processes. In this shape, macrophages can move freely as scavenger cells that phagocytose dying cells or cellular debris. These activated cells often signal cytokine activation that rapidly stimulates neighboring immune cells, which secrete tumor necrosis factor-α and increase inflammation (Aloisi 2001). In general, activated macrophages/microglia remove cellular debris during development and in adult tissue. Although ramified macrophages were originally considered resting macrophages and a precursor to activated macrophages, we now know that ramified macrophages also maintain extracellular fluid, transmitter inactivation, and synaptic pruning (Stevens et al. 2007).

Macrophages interact with sensory hair cells, non-sensory cells, and neural cells in the inner ear of several animal models of noise-induced hearing loss (see reviews by Hirose et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2017; Kalinec et al. 2017; Wood and Zuo 2017; Watson et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2018; Frye et al. 2019; Warchol 2019). In human cochleae, macrophages have distinct morphology in different regions of cochlear specimens from donors who range from 52- to 88-year-old and have no known pathology other than the aging process (O’Malley et al. 2016). To better understand how macrophages and cochlear inflammation affect age-related degeneration of cochlear structures and declines in auditory function, we need to characterize changes in activation states and the phenotypic heterogeneity of macrophages in aged cochleae.

Unlike acute cochlear injury, such as noise-induced hearing loss, cochlear cell degeneration with aging is a chronic change. For example, a significant physiological loss of sensory hair cells, non-sensory cells, or neural cells in the AN may not be identified for months or even years. To understand how macrophages affect cochlear immunity in response to the slow degeneration of sensory hair cells, Frye et al. (2017) examined changes in the distribution, number, and morphology of macrophages in different age groups of C57BL/6 J mice, a model of age-related loss of sensory hair cells. As these mice aged, Frye et al. (2017) uncovered dynamic changes in macrophage number and morphology. Macrophages with an amoeboid shape spatially correlated with the degeneration of sensory hair cells, demonstrating that macrophage activation occurs at the sensory epithelium site where death of hair cells begins. These findings suggest that macrophages change their active state in response to the cochlear environment that is pathologically changed by sensory hair cell loss. They also suggest that the initial macrophage-derived inflammatory response may contribute directly to degeneration of sensory hair cells.

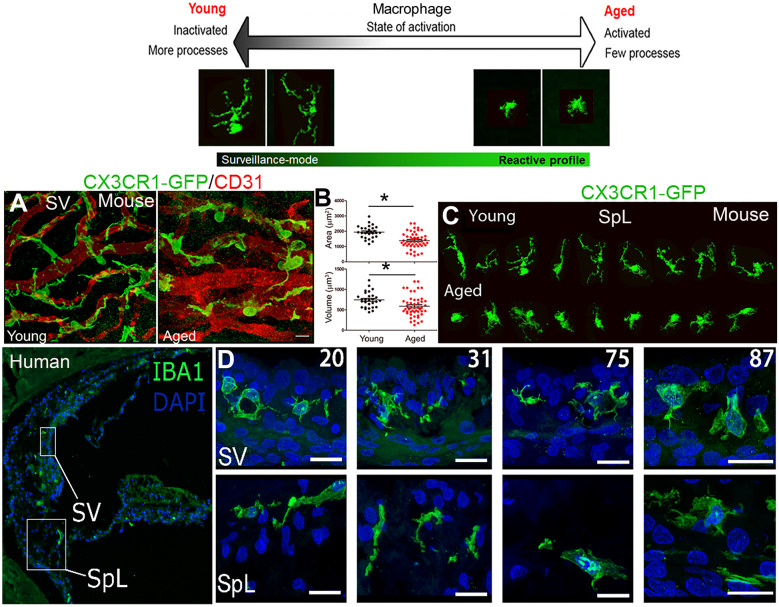

Macrophages may also be involved in degeneration of the SV in the cochlear lateral wall. In this region, the integrity of the strial microvasculature maintains the blood-labyrinth barrier and ensures proper function of cells within the SV, where the endocochlear potential (EP) is generated (Gratton et al. 1996; Shi 2016). With aging, the strial microvasculature shows pathological changes that include fewer capillaries, dilated capillaries, merged capillaries, thickened basement membrane, and altered transport of charged macromolecules (Gratton et al. 1997; Thomopoulos et al. 1997; Saitoh et al. 1995; Ohlemiller et al. 2008) (Fig. 2a). Age-related changes to macrophages and strial blood-labyrinth barrier occurred around the non-sensory cells in the cochlear lateral wall, suggesting that macrophage activation may contribute to strial microvasculature degeneration (Neng et al. 2015). Macrophages within the SV, also known as perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes (Zhang et al. 2012), are a key part of the blood-labyrinth barrier and may play an important role in maintaining the ionic, osmotic, or metabolic balance needed for EP generation, cochlear structural integrity, and auditory function. As shown in Fig. 2a (left panel), IBA1+ macrophages directly interact with endothelial cells in the SV of young adult mice. These macrophages appear “ramified-like,” with multiple cellular processes physically intermingled with CD31+ endothelial cells of the strial capillary network, suggesting the involvement of macrophages in regulating blood-labyrinth barrier integrity. This hypothesis is supported by an elegant in vitro study by Neng et al. (2015) showing the presence of perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes is necessary for endothelial cell tube formation and stability.

Fig. 2.

Age-related morphological changes in macrophages in the stria vascularis of mouse and human cochleae. The schematic (the top panel) shows two forms of macrophages (Davis et al. 1994). (a) Strial microvasculature (CD31+ endothelial cells, red) and GFP+ macrophages (green) in young adult and aged CX3CR1-GFP mice show macrophage pathology and their abnormal spatial relationships to the microvasculature. Images were taken from whole-mount preparations of the stria vascularis (SV). (b) Morphometric analysis of strial macrophages reveals significantly reduced volume and area in aged (n = 45) versus young-adult (n = 28) CX3CR1-GFP mice; *p < 0.01 (Student’s unpaired t-test). (c) Aged-related morphological alterations of macrophages in the spiral ligament (SpL) from tissues of CX3CR1-GFP mice. The macrophages were randomly selected from the whole-mount preparations of the spiral ligaments from young-adult and aged animals. (d) Strial macrophages from sections of human temporal bone show age-related changes like those seen in aged mice in (a). Age of donor is indicated in white at the top. Scale bars in (µm) = 20. Images in d were modified from Noble et al (2019)

To study age-related phenotypic changes in macrophages, we examined macrophages in the cochlear lateral wall of aged CX3CR1-GFP mice (Fig. 2a, b. c), which express EGFP under control of the endogenous Cx3cr1 locus. This mouse model has been used to examine pathological changes in macrophages in the peripheral auditory system (Hirose et al. 2005; Kaur et al. 2015). In contrast to the ramified shape in young adult mice, aged macrophages reduce their process number and cellular volume, and they appear less ramified (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, interactions (contacts) between macrophages and the microvasculature were disrupted in the SV of aged mice. In the SpL of these aged mice, macrophages were clearly transformed to an active state with an amoeboid shape (Fig. 2c). These findings aligned with a previous study showing that aged strial macrophages stain positive for the lectin griffonia simplicifolia (IB4), a marker of macrophage activation (Neng et al. 2015). This study also found significantly fewer macrophages in the SV of aged mice, which correlated with loss of capillary density. These observations suggest that the aging process significantly changes the state and phenotype of macrophages. They also suggest that deficiency (and/or dysfunction) of macrophages may disrupt the integrity of the blood-labyrinth barrier, resulting in enhanced cochlear inflammatory responses, cochlear cell degeneration, and hearing loss.

The ability to compare results from animal models and human temporal bones offers an unparalleled opportunity to address both basic science and translational questions about how cochlear macrophages and the innate immune system affect human presbyacusis. However, limited availability of human temporal bones that were properly prepared for cellular and molecular assays has hindered the progress of our investigations into the role of macrophages and the inflammatory response in the aged human cochlea. In a recent study, we compared 12 human temporal bones obtained from donors aged from 20 to more than 89 years. In these bones, we identified age-dependent changes in macrophage morphology in both the cochlear lateral wall and AN (Noble et al. 2019). We found that macrophages of both the SV and SpL have fewer processes and increased cytoplasmic volume around the nucleus in older donors than younger donors, suggesting that aged macrophages transform to a more active state (Fig. 2d). Although we did not see significant age-related changes in macrophage numbers in the cochlear lateral wall, we did see more macrophages in the AN of the middle turns of human temporal bones from older donors. We also saw more physical interactions between macrophages and myelinating glial cells and neuronal components in the ANs of the older donors (unpublished observation). These findings revealed that with aging, macrophage activation increases in the AN and cochlear lateral wall of the human inner ear, suggesting that activation of cochlear macrophages and chronic inflammation influence presbyacusis.

Understanding how inflammation and macrophage activation contribute to sensorineural hearing loss has become an important area of research (see reviews Hu et al. 2017; Kalinec et al. 2017; Watson et al. 2017; Wood and Zuo 2017). Our current knowledge of the cochlear immune response is largely centered on how macrophages are involved in cochlear development, and on their role in hearing loss after cochlear injury (Rai et al. 2020; Fredelius et al. 1990; Bhave et al. 1998; Sekiya et al. 2001; Hirose et al. 2005; Frye et al. 2017; Wood and Zuo 2017; Kishimoto et al. 2019; Kaur et al. 2015, 2018; Brown et al. 2017; Panganiban et al. 2018; Noble et al. 2019; Warchol 2019). To better understand the causes of pathophysiological changes in presbyacusis, we need more studies on the molecular mechanisms that mediate macrophage activation and abnormal interaction between macrophages and cochlear cells. Although many studies have uncovered molecular mechanisms that regulate microglia/macrophage dysfunction in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, few have deciphered the molecular mechanisms of macrophage dysregulation in aged cochleae. Here we will discuss two regulatory systems of inflammation and macrophage activity: complement dysregulation and the related NLRP3 inflammasome.

COMPLEMENT SIGNALING AS A REGULATOR OF MACROPHAGE FUNCTION

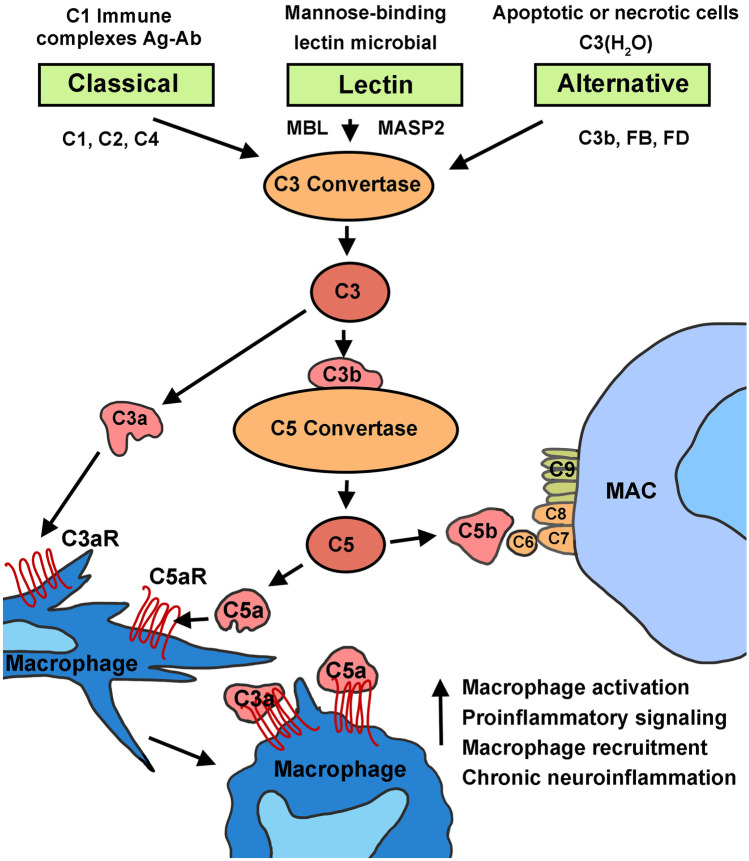

The complement system is a key component of the innate immune system that contributes to rapidly clearing dead or degenerating cells and pathogens by mounting a non-specific defense response to injury or other pathological conditions. Dysregulation of the complement cascade plays a vital role in age-related neurodegenerative disorders (Schnabolk et al. 2014; Armento et al. 2021). The complement system comprises more than 40 soluble and membrane-bound proteins. This system can be activated via three distinct routes: the classical pathway, the lectin pathway, and the alternative pathway (Fig. 3). All of these pathways converge on the cleavage of complement component 3 (C3), the most abundant complement protein (Merle et al. 2015; Sarma and Ward 2011). When cleaved, C3b fragments covalently bind receptors on the surface of foreign bodies and apoptotic cells, signaling phagocytes to engulf opsonized targets. Also, when C3b complexes generate, a C5 convertase begins to form, which triggers the membrane attack complex (MAC) that causes transmembrane pores to form on the cell surface, leading to cell lysis (Ramaglia et al. 2008; Sarma and Ward 2011). This rapid complement cascade helps phagocytic cells (such as macrophages) of the innate immune system recognize and eliminate pathogens.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of the three pathways of the complement system that converge on C3 to activate macrophages. The classical and lectin pathways involve cleavage of C4 and C2 to make C3 convertase. Activation of C3 induces production of the cleavage products C3a and C5a, which promote inflammation. The alternative pathway can spontaneously act on C3b through Factor B (FB) in a feedback loop. Activation of C3 and the terminal pathway ultimately leads to formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) and cell lysis. Binding of C3a and C5a with their specific receptors on macrophages triggers release of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules, leading to macrophage activation

Three Complement Pathways

The classical pathway is triggered by cleavage of C1 into three molecules: C1q, C1s, and C1r. This cleavage prompts cleavage of C4 and C2 to form the C3 convertase, C4bC2a, and stimulates generation of the MAC complex (Sarma and Ward 2011; Fig. 3). Similarly, the lectin pathway is triggered when mannose-binding lectin (MBL) binds the surface of foreign cells, causing a conformational change that generates MBL-associated protein 2. Like C1q, MBL-associated protein 2 (MASP2) cleaves C4 and C2 to form C4bC2a, prompting C3 cleavage and activating the MAC pathway (Sarma and Ward 2011). Unlike the classical and lectin pathways, the alternative pathway does not require pathogens or immune complexes. In this pathway, complement is continuously activated to assist with the rapid and acute response to pathogens (Merle et al. 2015; Morgan and Harris 2015). When the alternative pathway is activated, C3 is spontaneously hydrolyzed and a C3bB complex forms with complement Factor B. This process occurs spontaneously and at a low continuous rate, which has been defined as “tick-over” (Thurman and Holers 2006). C3bB is then cleaved by complement Factor D to form a C3bBb convertase, activating the MAC pathway (Merle et al. 2015; Sarma and Ward 2011).

Synthesis of Complement Proteins and Macrophage Activation

Multiple cell types can synthesize complement proteins. Hepatocytes in the liver generate most of the complement molecules. Tissue resident and migratory immune cells, including macrophages, produce initiator complement components (Heeger et al. 2005; Peake et al. 1999; Strainic et al. 2008). In nervous tissue, microglia/macrophages, neurons, and glial cells express surface-bound and soluble complement proteins (de Jonge et al. 2004; Lian et al. 2016; Schafer et al. 2012). In the peripheral auditory system, the developing AN secretes high levels of classical complement components, demonstrating that complement signaling may play a key role in nerve development during hearing onset (Brown et al. 2017).

The target cell types for the bioactive complement subunits are immune cells, which express a variety of complement receptors and regulators on their cell surface (e.g., receptors C3aR and C5aR of macrophages) (Dustin 2016; Fig. 3). As such, the complement system is considered the primary effector of soluble proteins in the innate immune system (Fearon and Locksley 1996). Given the phagocytic nature typically attributed to macrophages, complement molecules assist with phagocytosis by targeting cells and debris for engulfment, a process called opsonization. For example, after light-induced retinal degeneration, deletion of the C5aR receptor results in reduced macrophage recruitment and complement component expression (Song et al. 2017). Deletion of the C3 convertase regulator receptor (Crry) induces microglial cell priming, and AD-mouse models deficient in Crry have enhanced amyloid beta plaque and accumulation of degenerating neurons (Ramaglia et al. 2012; Wyss-Coray et al. 2002). Furthermore, deficiency of complement regulator Cd59a leads to enhanced expression of complement components with age in the retinal pigment epithelium choroid (Herrmann et al. 2015). Thus, dysregulation of complement gene expression or protein function contributes to impaired activity of resident macrophages.

Complement Dysregulation in Age-related Neurodegeneration

Dysregulation of the complement cascade plays a vital role in age-related neurodegenerative disorders (Schnabolk et al. 2014; Armento et al. 2021). During aging processes, dysregulation of complement signaling may significantly contribute to cochlear pathology. A common aspect of aging includes recurrent insults (e.g., sterile inflammation may develop from repeated sound exposures over one’s lifetime). Exposure to lipopolysaccharides is a common model of inflammatory response in rodents. Long-term systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharides activates the classical complement signaling pathway and enhances the inflammatory microenvironment in the brain (Bodea et al. 2014). This persistent inflamed microenvironment precedes neural cell death and is rescued in C3-deficient mice (Kuehn et al. 2008). During age-related macular degeneration in these mice, localized inflammation, excessive leakiness, and neovascularization were dampened (Tan et al. 2015). In hypo-ischemic injury, immune cell activity and resulting neural cell loss are linked to the signaling of C1q and C3 (Ten et al. 2005). Although, C1qa-deficient mice did not show differences in developmental synaptogenesis nor auditory function (Calton et al. 2014), complement molecules (including C1s and Cfi) were enriched in the cochlea following noise injury (1 day after 120 dB sound pressure level and 2-h 1–7 kHz broadband noise exposure) (Patel et al. 2013). Consequently, cochlear aging may be due to dysregulated complement activation (e.g., upregulation of C3 and C1q; unpublished observations). This dysregulated complement-related inflammatory signaling would contribute to aberrant macrophage activity, resulting in damage to cochlear tissues (e.g., cochlear lateral wall and AN of aged cochlea) and declines in auditory function.

POTENTIAL ROLES OF NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME IN COCHLEAR CELL DEGENERATION

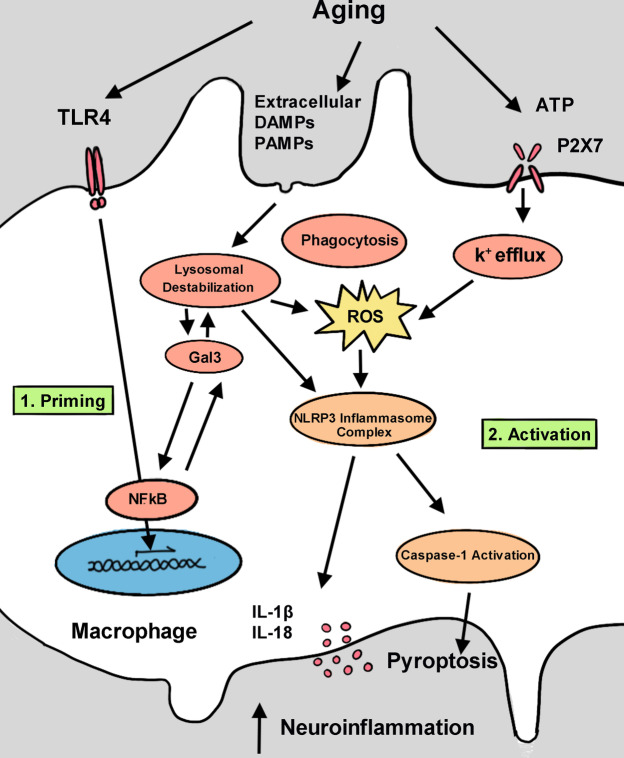

Inflammasomes are intracellular molecular complexes that are expressed in myeloid-derived cells, such as macrophages and microglia (Sarkar et al. 2009; Qu et al. 2007) (Fig. 4). Inflammasomes are triggered by infection or other cellular stress, resulting in maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines that further activate innate immune defenses (Schroder and Tschopp 2010; Guarda et al. 2011).

Fig. 4.

Schematic of NLRP3 inflammasome activation associated with macrophages in presbyacusis. During aging, many pathological factors (e.g., TRL4) can evoke expression of Gal-3. Gal-3 then activates NFκB through a positive-feedback loop. Also, the presence of extracellular DAMPs and PAMPs triggers lysosomal damage as shown by Gal-3 aggregation on ruptured lysosomes. Furthermore, Gal3 prevents clearance of ruptured lysosomes and enhances generation of NLRP3 inflammasomes. Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasomes can be activated by K+ efflux via binding the P2X7 receptor. K+ efflux leads to mitochondrial damage and ROS production, critical elements of inflammasome assembly. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes leads to maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, and activation of caspase 1. This pathway results in chronic neuroinflammation that may contribute to the degeneration of cochlear cells and presbyacusis

Inflammasomes use pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which are expressed on macrophages, to detect microbial patterns and other danger signals. PRRs can be further delineated by their extracellular or intracellular location (Jo et al. 2016; Schroder and Tschopp 2010). Extracellular PRRs are represented by C-type lectins and Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which can detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (Jo et al. 2016). Intracellularly, PRRs can detect DNA and RNA. The signal cascade that occurs because of a PAMP or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) binding a PRR differs depending on the unique combination of PRR and PAMP or DAMP (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). A specific subset of intracellular PRRs, known as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLRs), can detect PAMPs similar to the PRRs discussed above. They can also detect endogenous signals that indicate DAMPs (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). A specific NLR, NLRP3, is involved with the NLRP3 inflammasome, which leads to the development of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) (Jo et al. 2016).

The NLRP3 inflammasome was discovered when researchers found a link between inflammatory conditions and mutations in the genes responsible for the NLRP3 inflammasome (Hoffman et al. 2001; Aganna et al. 2002). More specifically, genes for the NLRP3 inflammasomes are expressed within the cochlea (Nakanishi et al. 2017). Few studies have examined inflammasome-related pathways in cochlea, but several have studied the NLRP3 inflammasome in age-related chronic inflammatory conditions, such as age-related macular degeneration (Gao et al. 2015), cardiovascular disease (North and Sinclair 2012), and Alzheimer’s disease (Halle et al. 2008). Several DAMPs that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome are elevated with age (Cordero et al. 2018). Studies have proposed that the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway could promote caspase-1 and IL-1β to activate macrophages and microglia, thereby contributing to chronic sterile inflammation throughout the body with aging (Youm et al. 2013). These studies suggest that in age-related hearing loss, the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway contributes to macrophage activation and abnormal macrophage-glia interactions in cochlea (Noble et al. 2019).

NLRP3 Inflammasome Priming

The first step in activating the NLRP3 inflammasome is upregulation of NLRP3, also known as priming (Jo et al. 2016; Fig. 4). Several candidate pathways contribute to inflammasome priming in both aged and noise-exposed macrophages of cochlea, and they all converge on increased expression of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), which ultimately induces expression of NLRP3 (Schroder and Tschopp 2010). The NFκB pathway can be induced by interacting with TLR4. Indeed, TLR4 and NFκB downstream signals were upregulated after traumatic cochlear noise exposure (Zhang et al. 2019). Amyloid plaques, the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, also interact with TLR4, possibly contributing to inflammasome priming (Song et al. 2011). Further, the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF was linked to inflammasome priming, which is significantly upregulated in aging people (de Gonzalo-Calvo et al. 2010; Bauernfeind et al. 2016). When macrophages derived from murine bone marrow were incubated with TNF for 2 h, NLRP3 expression increased, whereas IL-1β expression did not change. This result shows that the inflammasome was primed but not yet activated (Bauernfeind et al. 2016), and that the primed inflammasome was activated after being primed with TNF but not without TNF (Bauernfeind et al. 2016).

NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

Once primed, NLRP3 can be activated by PAMPs or DAMPs. The NLRP3 inflammasome responds to a variety of DAMPs, many of which are found in aging tissues (Cordero et al. 2018). These DAMPs include ATP (Sadatomi et al. 2017), amyloid-β fibrils (Halle et al. 2008; Abderrazak et al. 2015), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Abderrazak et al. 2015). In some tissues, such as blood monocytes, stimulation of the NFκB pathway primes and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. However, in macrophages, the NFκB pathway only primes; a second signal is still needed for activation (Netea et al. 2009).

An array of molecules can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, suggesting that these molecules may not directly interact with NLRP3, but rather rely on common triggers (Yang et al. 2019). One common trigger is the fluctuation of varying ions, such as the efflux of K+ and Cl− (Muñoz-Planillo et al. 2013; Green et al. 2018), influx of Na+(Gianfrancesco et al. 2019), and Ca+ variations (Murakami et al. 2012). Extracellular ATP causes efflux of K+ by binding the P2X7 receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel (Próchnicki et al. 2016). Also, adding extracellular ATP led to increased P2X7 receptors in cochlea and reduced EP (Muñoz et al. 1995; Housley et al. 1999).

Another trigger is the production of ROS (Zhou et al. 2011). We do not fully understand how ROS activates the inflammasome, but a newly discovered serine-threonine kinase, NEK7, interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome and regulates ROS signaling (Shi et al. 2016). Also, the anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 prevented activation of NADPH oxidase in microglia, which reduced synthesis of NLRP3 and its downstream effectors (Gao et al. 2020). Also, traumatic noise exposure induces production of ROS in cochlea (Shi et al. 2003; Yamashita et al. 2005; Henderson et al. 2006). ROS levels are also higher in aging neural tissue, implicating the inflammasome in age-related hearing loss (Lee et al. 2000). Moreover, in the senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 model, which shows premature hearing loss and cochlear neural degeneration, lipid peroxidation products were significantly higher at 9 months of age. This finding indicates increased oxidative stress (Menardo et al. 2012), which could contribute to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and, ultimately, chronic inflammation.

Lysosomal destabilization influences neurodegenerative diseases and may activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Hoffman et al. 2001; Hafner-Bratkovič et al. 2012). Lysosomal destabilization occurs during the normal aging process, which could link increased activation of macrophages to aging cochlea (Shi et al. 2003; Yamashita et al. 2005; Henderson et al. 2006). A molecule that may affect this process is galectin-3 (Gal-3). This β-galactoside-binding protein, originally named Mac-2, was discovered on thioglycolate-elicited macrophages (Ho and Springer 1982; Dumic et al. 2006). Gal-3 contains a C-terminal domain that recognizes carbohydrates (common in all galectins), and a unique N-terminal domain that supports the formation of oligomers (Dumic et al. 2006). Plasma levels of Gal-3 are elevated in several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Wang et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2016; Siew et al. 2019). Gal-3 expression is also correlated with aging. Indeed, immunohistochemistry of brain tissues from aged monkeys showed greater levels of Gal-3-positive microglia than that of young controls (Shobin et al. 2017). Also, single-cell RNA sequencing of microglia revealed upregulated Lgals3, the gene coding for Gal-3, in aged microglia (Hammond et al. 2019). In a mouse model of Huntington’s disease, Gal-3 puncta were seen with lysosomal-associated membrane proteins (Siew et al. 2019), and these Gal-3 puncta indicate lysosomal destabilization (Aits et al. 2015). Gal-3 also acts as a sensor by attaching to the normally luminal β-galactosidases of lysosomes when they become exposed after loss of structural integrity (Siew et al. 2019). Based on co-immunoprecipitation experiments, Gal-3 interacts with the adapter apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC) of the NLRP3 inflammasome to aids in its activation (Simovic Markovic et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2018). Gal-3 also induces and is promoted by the NFκB pathway in a positive feedback loop, which could aid in priming the NLRP3 inflammasome (Zhao et al. 2017; Siew et al. 2019; Fig. 4). In Huntington’s disease, diabetic retinopathy, and Alzheimer’s disease, Gal-3 knockout markedly reduced inflammation (O’Malley et al. 2016). Multiple studies have linked Gal-3 with microglia and neurodegenerative disorders, but few have linked the molecular changes of the cochlea and hearing loss. Although no reports describe protein expression of Gal-3 in cochlea, a study that immunostained aged human cochlea for CD68, a marker of the lysosomal/endosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein, found punctate staining patterns that are often associated with Gal-3 (Salminen et al. 2012). Activated macrophages and lysosomal punctate staining patterns in cochlea suggest that Gal-3 may affect presbyacusis, similar to other neurodegenerative disorders. Thus, Gal-3 is a promising target for future research on the connection between activated macrophages and lysosomal destabilization in the cochlear pathophysiological conditions (Salminen et al. 2012; Noble et al. 2019).

Downstream Effects of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

When the NLRP3 inflammasome is primed and activated, the complex recruits ASC, which then recruits and activates pro-caspase-1 to form a protein complex (Bergsbaken et al. 2009). Pro-caspase-1 then undergoes cleavage and activation, which completes the maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (Youm et al. 2013). The activated caspase-1 then initiates pyroptosis, a cell death cascade that starts by forming plasma-membrane pores that lead to the loss of ion homeostasis. This process ultimately culminates in cell lysis and failure to contain the pro-inflammatory intracellular contents (Wang et al. 2019; Fig. 4). Pyroptosis is one way that the NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to neural degeneration (Lee et al. 2019). Neuron cell death is triggered by IL-1β production, which increases recruitment of additional microglia and intensifies their neurotoxicity capabilities (Qiao et al. 2017). Also, caspase-1 can induce the caspase-7/PARP1/AIF pathway, contributing to neuron cell death in Parkinson’s disease (Jha et al. 2010). In Parkinson cell lines, overexpression of caspase-7 diminished the anti-apoptotic effects of caspase-1 inhibitors (Hoffman et al. 2001).

As we have already described, the NLRP3 inflammasome could be activated in multiple ways that result in cochlear inflammation. Other factors that could link the NLRP3 inflammasome to cochlear inflammation include gain-of-function mutations on cochlear macrophages. In one study, researchers performed genetic mapping on patients with auto-inflammatory diseases known as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. In these patients, they discovered a gain-of-function mutation in the NLRP3 inflammasome that leads to activation of the inflammasome without an activation signal (Nakanishi et al. 2017; Nakanishi et al. 2018). This aberrant activation in cochlear macrophages leads to increased IL-1β production and sensorineural hearing loss (Goldbach-Mansky et al. 2006; Nakanishi, et al. 2017). Interestingly, other studies found that blocking IL-1β could improve or completely reverse hearing loss, implicating IL-1β as a major cause of hearing loss (Goldbach-Mansky et al. 2006; Nakanishi et al. 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

Traditionally, the environment of the human inner ear was considered immune-privileged. With abundant evidence, we now know that this paradigm is outdated and invalid. We have gained an understanding of how macrophages migrate and persist during development, and are present with other immune cells. However, we still lack the knowledge of how precisely macrophages influence cochlear maturation and age-related structural and functional maintenance and degeneration.

Based on previous observations, activated cochlear macrophages have an intricate relationship with resident cells in both mouse and human ears. This relationship suggests that dysregulation of immune cells influences pathophysiological changes in many cochlear cell types in aged cochlea, particularly in the cochlear lateral wall and AN. These changes are similar to the inflammaging contributions of macrophages and microglia seen in other age-related neurodegenerative disorders, such as age-related macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (Denver and McClean 2018; Yang et al. 2019; Jha et al. 2010).

Complement signaling has a clear effect on age-related and neurodegenerative disorders in mouse models (Lian et al. 2016; Qin et al. 2007; Tan et al. 2015; Bodea et al. 2014; Scholl et al. 2008). Complement molecules were associated with synapse loss, neural cell death, and inflammatory microenvironments in models of Alzheimer’s disease, age-related macular degeneration, and multiple sclerosis (Qin et al 2007; Tatomir et al. 2017; Armento et al. 2021). Similar characteristics were identified in aged human cochlea, suggesting that dysregulation of the complement system contributes to inflammaging of the cochlea and promotion of presbyacusis.

Comparably, the NLRP3 inflammasomes affects macrophage and microglia activation in neurodegenerative disorders (Jha et al 2010; Lee et al 2019; Bauernfeind et al 2009; Bauernfeind et al 2016). The presence of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the cochlea (Nakanishi et al. 2017) suggests that macrophage-derived inflammasomes may have a role in exacerbating damage in the cochlea during presbyacusis. Additional studies of immune cells in aged cochlea may reveal potential therapeutic strategies for targeting macrophages/microglia to treat presbyacusis. Furthermore, targeting inflammatory signaling, such as complement pathways or NLRP3 inflammasome priming and activation, in aged cochlea may uncover new therapeutics for treating presbyacusis and other forms of sensorineural hearing loss.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jayne Ahlstrom and Crystal Herron for editing the manuscript, Nathaniel Parsons and Abigail McGaha for their comments and help with the references, and Aileen Shi and Rachel Eisenhart for creating the schematics of the complement pathways and NLPR3 inflammasome activation.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health including P50DC000422 (H.L.), SFARI Pilot Award #649452 (H.L.), and K18 DC018517 (H.L.).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abderrazak A, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: from a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol. 2015;4:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aganna E, et al. Association of mutations in theNALP3/CIAS1/PYPAF1 gene with a broad phenotype including recurrent fever, cold sensitivity, sensorineural deafness, and AA amyloidosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2445–2452. doi: 10.1002/art.10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altermatt HJ, Gebbers JO, Muller C, Arnold W, Laissue JA. Human endolymphatic sac: evidence for a role in inner ear immune defence. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1990;52(3):143–148. doi: 10.1159/000276124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aits S, et al. Sensitive detection of lysosomal membrane permeabilization by lysosomal galectin puncta assay. Autophagy. 2015;11(8):1408–1424. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1063871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F. Immune function of microglia. Glia. 2001;36(2):165–179. doi: 10.1002/glia.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armento A, Ueffing M, Clark SJ. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(10):4487–4505. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03796-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autieri MV. cDNA cloning of human allograft inflammatory factor-1: tissue distribution, cytokine induction, and mRNA expression in injured rat carotid arteries. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228(1):29–37. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1612.PMID8912632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F, et al. Aging-associated TNF production primes inflammasome activation and NLRP3-related metabolic disturbances. J Immunol. 2016;197(7):2900–2908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, Hornung V and Latz E (2009) Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 183(2): 787–791. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(2):99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave SA, Oesterle EC, Coltrera MD. Macrophage and microglia-like cells in the avian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398(2):241–256. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<241::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodea LG, Wang Y, Linnartz-Gerlach B, Kopatz J, Sinkkonen L, Musgrove R, Kaoma T, Muller A, Vallar L, Di Monte DA, Balling R, Neumann H. Neurodegeneration by activation of the microglial complement-phagosome pathway. J Neurosci. 2014;34(25):8546–8556. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5002-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LN, Xing Y, Noble KV, Barth JL, Panganiban CH, Smythe NM, Bridges MC, Zhu J, Lang H. Macrophage-mediated glial cell elimination in the postnatal mouse cochlea. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:407. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calton MA, Lee D, Sundaresan S, Mendus D, Leu R, Wangsawihardja F, Johnson KR, Mustapha M. A lack of immune system genes causes loss in high frequency hearing but does not disrupt cochlear synapse maturation in mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e94549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-J, et al. Galectin-3 enhances avian H5N1 influenza A virus–induced pulmonary inflammation by promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Am J Pathol. 2018;188(4):1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero MD, Williams MR, Ryffel B. AMP-activated protein kinase regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EJ, Foster TD, Thomas WE. Cellular forms and functions of brain microglia. Brain Res Bull. 1994;34(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo D, et al. Differential inflammatory responses in aging and disease: TNF-α and IL-6 as possible biomarkers. Free Radical Biol Med. 2010;49(5):733–737. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge RR, van Schaik IN, Vreijling JP, Troost D, Baas F. Expression of complement components in the peripheral nervous system. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(3):295–302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver P, McClean PL. Distinguishing normal brain aging from the development of Alzheimer’s disease: inflammation, insulin signaling and cognition. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(10):1719–1730. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.238608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumic J, Dabelic S and Flögel M (2006) Galectin-3: an open-ended story, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects, 1760(4), pp. 616–635. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dustin ML (2016) Complement receptors in myeloid cell adhesion and phagocytosis. Microbiology spectrum 4(6). 10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0034-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eckert MA, Harris KC, Lang H, Lewis MA, Schmiedt RA, Schulte BA, Steel KP, Vaden KI, Dubno JR (2020) Translational and interdisciplinary insights into presbyacusis: a multidimensional disease Hear Res 108109. 10.1016/j.heares.2020.108109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fearon DT and Locksley RM (1996) The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science (New York, N.Y.) 272(5258): 50–53. 10.1126/science.272.5258.50 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fleischer K (1972) Das alternde Ohr: Morphologische Aspekte The aging ear: morphological aspects, HNO. 20(4):103–7. German. [PubMed]

- Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredelius L, Rask-Andersen H. The role of macrophages in the disposal of degeneration products within the organ of Corti after acoustic overstimulation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1990;109(1–2):76–82. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MD, Ryan AF, Kurabi A. Inflammation associated with noise-induced hearing loss. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2019;146(5):4020. doi: 10.1121/1.5132545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MD, Yang W, Zhang C, Xiong B, Hu BH. Dynamic activation of basilar membrane macrophages in response to chronic sensory cell degeneration in aging mouse cochleae. Hear Res. 2017;344:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: activation and regulation in age-related macular degeneration. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2015/690243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, et al. Through reducing ROS production, IL-10 suppresses caspase-1-dependent IL-1β maturation, thereby preventing chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(2):465. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GA, Mills JH. Presbycusis. Lancet (london, England) 2005;366(9491):1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco MA et al (2019) Saturated fatty acids induce NLRP3 activation in human macrophages through K+ efflux resulting from phospholipid saturation and Na, K-ATPase disruption, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1864(7):1017–1030. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Goldbach-Mansky R, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1β inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):581–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schmiedt RA, Schulte BA. Age-related decreases in endocochlear potential are associated with vascular abnormalities in the stria vascularis. Hear Res. 1996;94(1–2):116–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schulte BA, Smythe NM. Quantification of the stria vascularis and strial capillary areas in quiet-reared young and aged gerbils. Hear Res. 1997;114(1–2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JP, et al. Chloride regulates dynamic NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(40):E9371–E9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812744115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarda G, et al. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):2529–2534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-β. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(8):857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TR, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of microglia throughout the mouse lifespan and in the injured brain reveals complex cell-state changes. Immunity. 2019;50(1):253–271.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Xing Y, Moore MW, Zhang J, Han D, Schulte BA, Dubno JR, Lang H. Sox10 expressing cells in the lateral wall of the aged mouse and human cochlea. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e97389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner-Bratkovič I, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophage cell lines by prion protein fibrils as the source of IL-1β and neuronal toxicity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(24):4215–4228. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1140-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger PS, Lalli PN, Lin F, Valujskikh A, Liu J, Muqim N, Xu Y, Medof ME. Decay-accelerating factor modulates induction of T cell immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;201(10):1523–1530. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D, et al. The role of oxidative stress in noise-induced hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2006;27(1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000191942.36672.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg S, Liberman MC. Spiral ligament pathology: a major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2001;2(2):118–129. doi: 10.1007/s101620010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann P, Cowing JA, Cristante E, Liyanage SE, Ribeiro J, Duran Y, Abelleira Hervas L, Carvalho LS, Bainbridge JW, Luhmann UF, Ali RR. Cd59a deficiency in mice leads to preferential innate immune activation in the retinal pigment epithelium-choroid with age. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(9):2637–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilding AC (1953) Studies on the otic labyrinth. VI. Anatomic explanation for the hearing dip at 4096 characteristic of acoustic trauma and presbycusis, Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 62(4):950–6. 10.1177/000348945306200402. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489(2):180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Rutherford MA, Warchol ME. Two cell populations participate in clearance of damaged hair cells from the sensory epithelia of the inner ear. Hear Res. 2017;352:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MK and Springer TA (1982) Mac-2, a novel 32,000 Mr mouse macrophage subpopulation-specific antigen defined by monoclonal antibodies, The Journal of Immunology, 128(3), p. 1221. Available at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/128/3/1221.abstract. [PubMed]

- Hoffman HM, et al. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29(3):301–305. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holness CL, Simmons DL (1993) Molecular cloning of CD68, a human macrophage marker related to lysosomal glycoproteins Blood 81(6):1607-1613. 10.1182/blood.V81.6.1607.1607 [PubMed]

- Housley GD et al (1999) Expression of the P2X receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel in the cochlea: implications for sound transduction and auditory neurotransmission. J Neurosci 19(19):8377-8388. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08377.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hu BH, Zhang C, Frye MD. Immune cells and non-immune cells with immune function in mammalian cochleae. Hear Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BH, Zhang C, Frye MD. Immune cells and non-immune cells with immune function in mammalian cochleae. Hear Res. 2018;362:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S, Srivastava SY, Brickey WJ, Iocca H, Toews A, Morrison JP, Chen VS, Gris D, Matsushima GK, Ting JP. The inflammasome sensor, NLRP3, regulates CNS inflammation and demyelination via caspase-1 and interleukin-18. J Neurosci. 2010;30(47):15811–15820. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4088-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Taghizadeh F, Steyger PS. Potential mechanisms underlying inflammation-enhanced aminoglycoside-induced cochleotoxicity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:362. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo E-K, et al. Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(2):148–159. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurga AM, Paleczna M, Kuter KZ. Overview of general and discriminating markers of differential microglia phenotypes. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:198. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaland M, Salvatore K. The psychology of hearing loss. The ASHA Leader. 2002 doi: 10.1044/leader.FTR1.07052002.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec GM, Lomberk G, Urrutia RA, Kalinec F. Resolution of cochlear inflammation: novel target for preventing or ameliorating drug-, noise- and age-related hearing loss. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:192. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Ohlemiller KK and Warchol ME (2018) Genetic disruption of fractalkine signaling leads to enhanced loss of cochlear afferents following ototoxic or acoustic injury. J Comp Neurol (5): 824–835. 10.1002/cne.24369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaur T, Zamani D, Tong L, Rubel EW, Ohlemiller KK, Hirose K, Warchol ME. Fractalkine signaling regulates macrophage recruitment into the cochlea and promotes the survival of spiral ganglion neurons after selective hair cell lesion. J Neurosci. 2015;35(45):15050–15061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2325-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley EM. Pathology and mechanisms of cochlear aging. J Neurosci Res. 2020;98(9):1674–1684. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd Iii AR, Bao J. Recent advances in the study of age-related hearing loss: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2012;58(6):490–496. doi: 10.1159/000338588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto I, Okano T, Nishimura K, Motohashi T, Omori K. Early development of resident macrophages in the mouse cochlea depends on yolk sac hematopoiesis. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1115. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn MH, Kim CY, Jiang B, Dumitrescu AV, Kwon YH. Disruption of the complement cascade delays retinal ganglion cell death following retinal ischemia-reperfusion. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87(2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki T, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Baba K, Kariya S and Paparella MM (2004) Age-related histopathologic changes in the human cochlea: a temporal bone study. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 131(6): 897–903. 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lang H, Nishimoto E, Xing Y, Brown LN, Noble KV, Barth JL, LaRue AC, Ando K, Schulte BA. Contributions of mouse and human hematopoietic cells to remodeling of the adult auditory nerve after neuron loss. Molecular Therapy : the Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2016;24(11):2000–2011. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. CD163: a specific marker of macrophages in paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(5):794–801. doi: 10.1309/QHD6YFN81KQXUUH6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva T, Dustin ML, Sykulev Y. ICAM-1 co-stimulates target cells to facilitate antigen presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, et al. MPTP-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia plays a central role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(2):213–228. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0124-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-K, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):294–297. doi: 10.1038/77046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone C, Le Pavec G, Meme W, Porcheray F, Samah B, Dormont D, Gras G. Characterization of human monocyte-derived microglia-like cells. Glia. 2006;54(3):183–192. doi: 10.1002/glia.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian H, Litvinchuk A, Chiang AC, Aithmitti N, Jankowsky JL, Zheng H. Astrocyte-microglia cross talk through complement activation modulates amyloid pathology in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2016;36(2):577–589. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2117-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DJ. Functional morphology of the mucosa of the middle ear and eustachian tube. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85(2 Suppl 25 Pt 2):36–43. doi: 10.1177/00034894760850S209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Li G, Noble KV, Li Y, Barth JL, Schulte BA, Lang H. Age-dependent alterations of Kir4.1 expression in neural crest-derived cells of the mouse and human cochlea. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;80:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Kämpfe Nordström C, Danckwardt-Lillieström N, Rask-Andersen H. Human inner ear immune activity: a super-resolution immunohistochemistry study. Front Neurol. 2019;10:728. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makary CA, Shin J, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC, Merchant SN. Age-related primary cochlear neuronal degeneration in human temporal bones. JARO. 2011;12(6):711–717. doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Yamazaki K, Kanzaki J, Hosoda Y. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural investigation of the human vestibular dark cell area: roles of subepithelial capillaries and T lymphocyte-melanophage interaction in an immune surveillance system. Anat Rec. 1997;249(2):153–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199710)249:2<153::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SN, Nadol JB (2010) Schuknecht’s pathology of the ear. Shelton, CT, People's Medical Pub. House.

- Menardo J, et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and autophagic stress as the key mechanisms of premature age-related hearing loss in SAMP8 mouse cochlea. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16(3):263–274. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT. Complement system part I — molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BP, Harris CL. Complement, a target for therapy in inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2015;14(12):857–877. doi: 10.1038/nrd4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz DJB, et al. Extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) in the endolymphatic compartment influences cochlear function. Hear Res. 1995;90(1–2):106–118. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Planillo R, et al. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, et al. Critical role for calcium mobilization in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(28):11282–11287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117765109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H, et al. Gradual symmetric progression of DFNA34 hearing loss caused by an NLRP3 mutation and cochlear autoinflammation. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(3):e181–e185. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H (2017) NLRP3 mutation and cochlear autoinflammation cause syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNA34 responsive to anakinra therapy, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences, 114(37):E7766–E7775. 10.2307/26487724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National Academy of Sciences (2016) The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: Hearing health care for adults: priorities for improving access and affordability, [PubMed]

- Neng L, Zhang F, Kachelmeier A, Shi X. Endothelial cell, pericyte, and perivascular resident macrophage-type melanocyte interactions regulate cochlear intrastrial fluid-blood barrier permeability. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2013;14(2):175–185. doi: 10.1007/s10162-012-0365-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neng L, Zhang J, Yang J, Zhang F, Lopez IA, Dong M, Shi X. Structural changes in thestrial blood-labyrinth barrier of aged C57BL/6 mice. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361(3):685–696. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2147-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, et al. Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1β in monocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2009;113(10):2324–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KV, Liu T, Matthews LJ, Schulte BA, Lang H. Age-related changes in immune cells of the human cochlea. Front Neurol. 2019;10:895. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2012;110(8):1097–1108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley JT, Nadol JB, Jr, McKenna MJ. Anti CD163+, Iba1+, and CD68+ cells in the adult human inner ear: normal distribution of an unappreciated class of macrophages/microglia and implications for inflammatory otopathology in humans. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(1):99–108. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Rice ME, Gagnon PM. Strial microvascular pathology and age-associated endocochlear potential decline in NOD congenic mice. Hear Res. 2008;244(1–2):85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah M, Biber K, Vinet J, Boddeke HW. Microglia phenotype diversity. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10(1):108–118. doi: 10.2174/187152711794488575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panganiban CH, Barth JL, Darbelli L, Xing Y, Zhang J, Li H, Noble KV, Liu T, Brown LN, Schulte BA, Richard S, Lang H. Noise-induced dysregulation of quaking RNA binding proteins contributes to auditory nerve demyelination and hearing loss. J Neurosci. 2018;38(10):2551–2568. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2487-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Hu Z, Bard J, Jamison J, Cai Q, Hu BH. Transcriptome characterization by RNA-Seq reveals the involvement of the complement components in noise-traumatized rat cochleae. Neuroscience. 2013;248:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peake PW, O'Grady S, Pussell BA, Charlesworth JA. C3a is made by proximal tubular HK-2 cells and activates them via the C3a receptor. Kidney Int. 1999;56(5):1729–1736. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta I, Vismara M, Novellino F, Donato A, Zaffino P, Scali E, Pirrone KC, Spadea MF, Malara N, Donato G. Innate immunity cells and the neurovascular unit. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3856. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Próchnicki T, Mangan MS, Latz E (2016) Recent insights into the molecular mechanisms of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, F1000Research, 5, p. 1469. 10.12688/f1000research.8614.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qiao C, et al. Caspase-1 deficiency alleviates dopaminergic neuronal death via inhibiting caspase-7/AIF pathway in MPTP/p mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(6):4292–4302. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia. 2007;55(5):453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Franchi L, Nunez G, Dubyak GR (2007) Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 179(3): 1913–1925. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1913 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rai V, Wood MB, Feng H, Schabla NM, Tu S, Zuo J. The immune response after noise damage in the cochlea is characterized by a heterogeneous mix of adaptive and innate immune cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15167. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaglia V, Daha MR, Baas F. The complement system in the peripheral nerve: friend or foe? Mol Immunol. 2008;45(15):3865–3877. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaglia V, Hughes TR, Donev RM, Ruseva MM, Wu X, Huitinga I, Baas F, Neal JW, Morgan BP. C3-dependent mechanism of microglial priming relevant to multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(3):965–970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111924109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask-Andersen H, Danckwardt-Lillieström N, Friberg U, House W. Lymphocyte-macrophage activity in the human endolymphatic sac. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;485:15–17. doi: 10.3109/00016489109128039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadatomi D (2017) Mitochondrial function is required for extracellular ATP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, Journal of Biochemistry, p. mvw098. 10.1093/jb/mvw098. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saitoh Y, Hosokawa M, Shimada A, Watanabe Y, Yasuda N, Murakami Y, Takeda T. Age-related cochlear degeneration in senescence-accelerated mouse. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Inflammaging: disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging. 2012;4(3):166–175. doi: 10.18632/aging.100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Mitra S, Mehta S, Raices R, Wewers MD. Monocyte derived microvesicles deliver a cell death message via encapsulated caspase-1. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(9):e7140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma JV, Ward PA. The complement system. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343(1):227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, Ransohoff RM, Greenberg ME, Barres BA, Stevens B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl HP, Charbel Issa P, Walier M, Janzer S, Pollok-Kopp B, Borncke F, Fritsche LG, Chong NV, Fimmers R, Wienker T, Holz FG, Weber BH, Oppermann M. Systemic complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140(6):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabolk G, Tomlinson S, Rohrer B. The complement regulatory protein CD59: insights into attenuation of choroidal neovascularization. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;801:435–440. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF (1955) Presbycusis, Trans Am Laryngol Rhinol Otol Soc. (59th Meeting): -18; discussion, 419–20. [PubMed]

- Schuknecht HF. Further observations on the pathology of presbycusis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1964;80:369–382. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1964.00750040381003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102(1 Pt 2):1–16. doi: 10.1177/00034894931020s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya T, Tanaka M, Shimamura N, Suzuki S. Macrophage invasion into injured cochlear nerve and its modification by methylprednisolone. Brain Res. 2001;905(1–2):152–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha SH, Kanicki A, Dootz G, Talaska AE, Halsey K, Dolan D, Altschuler R, Schacht J. Age-related auditory pathology in the CBA/J mouse. Hear Res. 2008;243(1–2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Dai C, Nuttall AL. Altered expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the cochlea. Hear Res. 2003;177(1–2):43–52. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X. Pathophysiology of the cochlear intrastrial fluid-blood barrier (review) Hear Res. 2016;338:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shobin E, et al. Microglia activation and phagocytosis: relationship with aging and cognitive impairment in the rhesus monkey. GeroScience. 2017;39(2):199–220. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9965-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siew JJ, et al. Galectin-3 is required for the microglia-mediated brain inflammation in a model of Huntington’s disease. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3473. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]