Abstract

As elderly people increasingly come to represent a higher proportion of the world’s population, various forms of dementia are becoming a significant chronic disease burden. The World Health Organization emphasizes dementia care as a public health priority and calls for more support for family caregivers who commonly play a significant, central role in dementia care. Taking care of someone with dementia is a long-term responsibility that can be stressful and may lead to depression among family caregivers. Depression and related behavioral and cognitive changes among caregivers could in turn affect the status and prognosis of the dementia patient. This review article explores depression in dementia caregivers and summarizes proposed mechanisms, associated factors, management and research findings, and proposes future research directions.

Keywords: Dementia, Depression, Caregiver, Caregiver burden, Activities of daily living, Functional status

Core Tip: The prevalence of depression among caregivers of patients with dementia is higher than that of the general population. The cause of depression in caregivers is complicated and thought to be related to the patients, caregivers and cultural backgrounds. Multifaceted treatment for depression is regarded as the current mainstream clinical intervention. In some areas, supplementation with smart technology for interventions to alleviate the burden and depression of caregivers could be considered. There are also some ideas and directions for future research included in the conclusion section of this review.

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common and serious health condition that is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. It can cause the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work, at school and within the family. According to the World Health Organization, over 264 million people globally suffer from major depressive disorder, which is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide[1]. The prevalence of depression among dementia caregivers is even higher than that of the general population[2]. Because patients with dementia suffer from impairment in cognitive functioning and activities of daily living (bathing, eating, etc.), the caregiver's quality of care to his or her patient or family member is central, and the caregiver is usually with the patient for several hours per day (or resides in the same house). Many studies have shown that the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) mutually affect the caregiver’s skills and are also reflexively influenced by the caregiver, so the caregiver's own physical and mental health is extremely important. The topics of depression and the burden of caregivers of dementia patients are popular in clinical research. One of the significant reasons is that interventions for caregiver burden and depression are still a great challenge and an unmet need in clinical practice.

Depression can cause a variety of psychological and physical problems and raise the risk of caregiver suicide[2]. It compromises caregivers’ physical health[3], reduces caregivers’ quality of life[4], and has been shown to cause caregivers to place patients with dementia in an institutional care facility more rapidly[5,6]. Depression in caregivers can also influence dementia patients’ cognitive status and has been associated with more rapid cognitive decline in the dementia patients studied[7].

Caregiver depression is producing a growing impact on existing medical care and insurance systems. Guterman et al[8] suggest that caregiver depression shows a significant association with increased emergency department use. They report that medical systems should specifically address patient- and caregiver-centered dementia care and suggest that improved health outcomes and lower costs for this high-risk population could be achieved.

Many studies have investigated the factors associated with dementia caregiver depression and explored various interventions to address it. The work presented in this review falls into several categories, including prevalence, mechanism, associated factors, management, and research trends of depression in caregivers of patients with dementia.

DEFINITION FOR BURDEN AND DEPRESSION IN CAREGIVERS

The author defined a family caregiver as an adult who directly provides observation, encouragement, assistance, or care that substitutes for a patient’s efforts related to the activities of elderly patients with dementia. Such activities may include assisting the dementia patient to complete housework cleaning or maintenance, managing economic affairs, facilitating and supervising activities outside the home, and the broad supervision and management of safety, legal, and medically related matters.

Caregiver burden

The author can summarize 4 characteristics on the formation and the source of caregiver burden: (1) Direct care work, assistance in daily activities for patients and implementation of medical care; (2) The gap between the caregiver’s expectations and the reality; (3) Breaking the personal routine of the caregiver; and (4) The feelings of taking on the responsibility of the caregiving role.

The caregiver burden has subjective and objective dimensions. The subjective burden refers to the stress and anxiety that the caregiver feels about his or her own situation and the feeling of being manipulated by the care recipient. Objective distress refers to the interference and change of the caregiver’s life habits and household caused by care work[9]. In addition to the above concepts, in clinical outpatient services, caregivers often ask for help and have distress due to the BPSD[10,11].

Caregiver depression

Depression (melancholia) is an emotional response to chronic frustration and disappointment. In psychopathology, it is an affective and emotional disorder[12]. The etiologies for melancholia can be divided into reactive or endogenous types. In general, the mildest form of depressive mood is difficult to distinguish from the experience of disappointment and loss. It is a common, recurrent, and impairing condition that can lead to future suicide attempts, interpersonal problems, unemployment, and psychosocial dysfunctions.

Approximately 80% of dementia patients are being cared for by their families in the community. It was found that patients spent an average of 6.5 years being cared for at home before they were sent to a nursing institution[13]. It takes an average of 4 to 8 h a day to care for elderly individuals with dementia. Fuh et al[14] reported that 56.6% of dementia caregivers care for patients for more than 8 h a day. In the early stage of dementia, family members assist patients with higher and more complex daily life functions, such as assistance in dealing with money or with medication problems. However, as the patient's disease progresses, part of the caregiver's care gradually changes to assisting with self-care, such as bathing, dressing, and eating. The safety of the patient becomes the focus, and the problem of urine or stool incontinence gradually develops. At the same time, the caregiver must also deal with the patient's behavioral disturbances. In the process of caring, caregivers have to face the gradual disappearance and changes of the personality of his or her loved one, and witness the process of degeneration, suffering, distress and facing death. In addition to the direct distress of caring for patients, caregivers also deal with family conflicts, financial problems, and employment problems and adapt themselves to the role of caregiving. Furthermore, family caregivers also play a role in the medical care process of patients, including providing the patient's illness history, describing symptoms, and assisting in medical care[13].

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CAREGIVER DEPRESSION

Many studies have investigated the quality of life of dementia caregivers and found that they experienced high levels of grief, ambivalence, and other psychological ailments[15]. Major depressive symptomatology was most common, reported by more than 50% of caregivers[16,17]. A meta-analysis study revealed that depression occurs in at least 1 in 3 caregivers of persons with dementia[18,19]. Some previous studies have also reported high rates of caregiver depression, approximately 30%–83%[20].

CLINICAL MECHANISMS OF DEPRESSION IN CAREGIVERS OF DEMENTIA PATIENTS

High prevalence rates of caregiver depression may be explained by several factors. Many mechanisms and models have been developed and tested, and the evolution in understanding depression in those who provide care to family members with dementia is introduced in this section.

Stress process model

The stress process model[21] proposes that caregiver demographics (such as age, sex, employment status, and relationship to the patient) are associated with and actively affect each part of the stress process and types of stress, including subjective stressors, objective stressors, the perception of those stressors, and outcomes such as caregiver burden and depression.

The stress process model assumes that various factors influence stress and coping reactions. Some factors are naturally protective bodily resources that decrease the negative effects of stress. Other associated factors may increase the effects of stress and render the individual more vulnerable to stress. The model suggests that caregiver outcomes are often influenced by subjective and objective stressors, role strains, and psychological strains and are balanced with mediating influences such as coping strategies and social support resources such as family, friends, and other social groups. Other caregiver distress studies identified similar variables present in the stress process model[22]. Caregivers’ mental health outcomes depend not only on objective factors such as the BPSD and number of caregiving hours worked, but also on the caregivers’ subjective appraisals of the individuals with dementia or the accompanying situations[23]. Many caregivers misunderstand that problematic behaviors are under dementia patients’ control. Caregivers making this assumption are more likely to be depressed than those who attribute the BPSD to the disease itself and accept them[23]. On the other hand, caregivers with a sense of purpose, more closeness with the patients, and higher competencies may more easily find positive rewards in this challenging situation[24,25]. Previous studies have indicated that caregiver outcomes, including a sense of self-efficacy in controlling upsetting thoughts about the patient, rather than mechanistically dealing with problematic behaviors or obtaining respite, are highly associated with improved caregiver outcomes[26-29].

Core stress and coping model

Previous studies[30] suggest a common core model for explaining the formation of caregiver distress. In this core model, BPSD are seen as basic stressors for informal caregivers, the caregivers’ personal perceptions of burden as key mediators are incorporated, and it is suggested that higher levels of caregiver burden are positively associated with worse caregiver outcomes.

Sociocultural stress and coping model

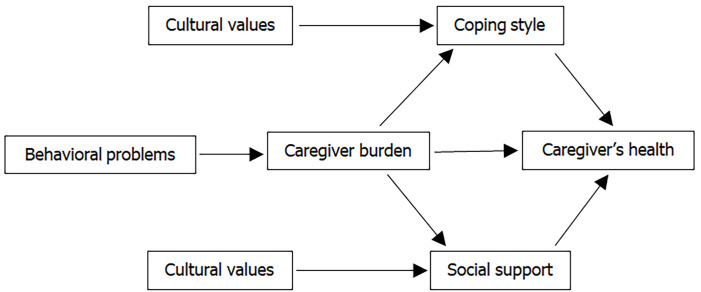

Aranda and Knight[31] suggest that culture and ethnicity play important roles in the stress and coping processes of caregivers to elderly individuals. Cultural and ethnic factors may even be associated with specific health disorders and disabilities and explain variations in caregivers’ appraisals of potential stressors. Knight and Sayegh[32] suggest a revised model (Figure 1) that takes cultural values into more robust consideration. They suggest that familism as a cultural value adds multidimensional effects and that values regarding social or familial obligations show more influence than family solidarity. Knight and Sayegh[32] further point out that the effects of cultural values and ethnicity on stress and coping processes are found to relate more to social support and coping styles than to caregiver burden. In summary, cultural values are, at best, indirectly related to the mental health of caregivers, which in turn affects the social and family support of dementia caregivers and further affects the way they respond to dementia patient(s) in their care. The authors suggest that these factors are at least indirectly associated with the mental health of caregivers.

Figure 1.

The sociocultural stress and coping model is based on the core stress and coping model and further takes cultural values into consideration.

Systemic family framework model

The psychological and dynamic dimensions within a family are thought to affect caregiver stress perceptions and coping processes. Acceptance of aversive experiences and a commitment to personal values by the caregiver are proven to be associated with challenges and experiences, including sadness and grief. Although there is usually one member of the family that assumes most caregiving responsibility, the caregiving process impacts the whole family.

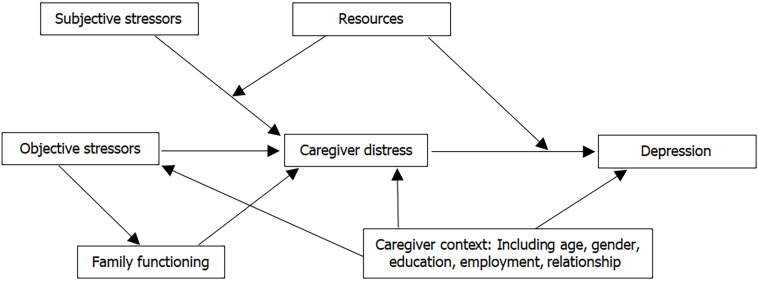

Mitrani et al[33] applied structural family theory[34] in studying the role of family functioning in caregiver stress and coping processes. They indicated that family functioning partially mediates the relationship between objective burden and caregiver distress in the stress process model (Figure 2). Mitrani et al[33] suggested that caregiver distress appraisal may be mitigated by any intervention that is best targeted at correcting problematic family interactions and preserving protective family patterns. Family interventions may enhance the participation of dementia patients in family activities, resolution of disagreements, and expressions of emotionality and further decrease expressed negative responses to the patient.

Figure 2.

Systemic family framework model is based on the stress process model and the family functioning is taken into consideration.

Activity restriction model

The Activity Restriction Model[35] suggests that the stresses of caregiving discourage one’s ability to engage in social and recreational activities, and this restriction is expected to contribute to depression. Mausbach et al[36] examined the activity restriction model in the context of dementia caregiver research. Their results suggest that activity restriction significantly mediated the relationship of the caregiving role and depression. On the other hand, they also found that depression acts as a key mediating factor of the caregiving role and activity restrictions. These findings support the use of social and recreational activities of dementia caregivers as opportunities for useful depression-improving behavioral interventions. Moreover, the caregiver’s participation in pleasurable activities (i.e., behavioral activation) could be promoted with behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches[37]. These results raise the importance and application of the activity restriction model in explaining and treating caregiver depression.

Suffering-compassion model

Previous studies suggest that caregivers’ perceived suffering of the dementia patients was significantly associated with caregiver depression[38]. The Suffering-Compassion Model demonstrates the relations among the dementia patient’s suffering, and the caregiver’s perceived suffering, intrusive thoughts, and compassion. The contribution of caregivers’ perceived suffering to caregiver depression is, however, mediated by their own personal intrusive thoughts. At the same time, caregiver compassion appears to moderate the relations of the caregiver’s perceived suffering and intrusive thoughts. If the caregiver had higher compassion, he or she was more likely to experience greater intrusive thoughts. It should be noted that the physical suffering of dementia patients may be more easily recognized than their psychological suffering[39]. This could therefore cyclically mediate caregiver perception, reaction, emotion, etc.

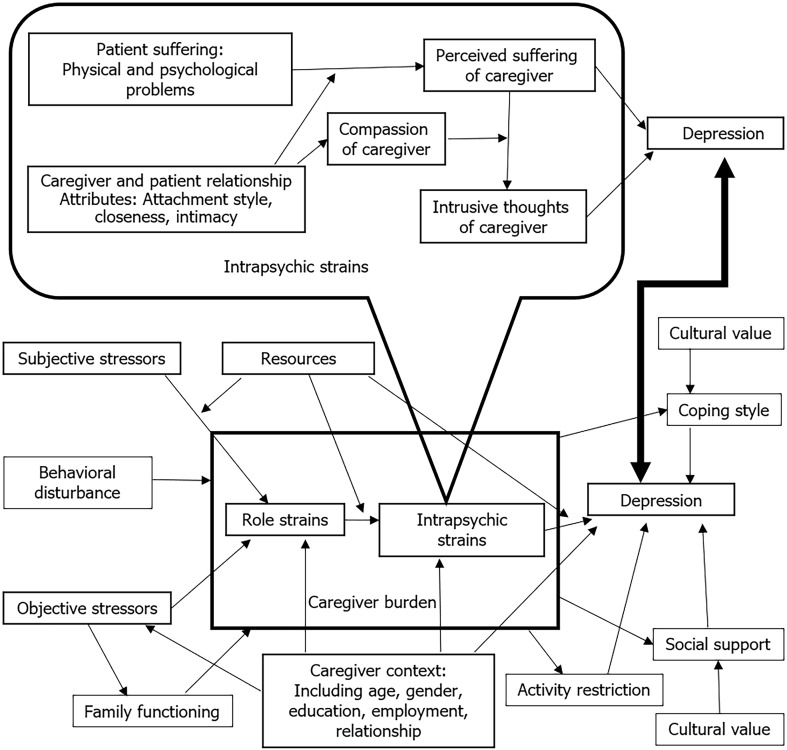

In summary, the author merged the above 6 common models for explaining caregiver depression, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A conceptual model includes the factors related to the caregiver depression. The figure is based on the stress process model and combined with core stress and coping model, sociocultural stress and coping model, systemic family framework model, activity restriction model, and suffering-compassion model.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH CAREGIVER DEPRESSION

It is important to explore all factors that may be relevant to the development of dementia caregiver depression. By understanding the relevant factors, treatment may be designed to improve caregivers’ mental health.

As dementia diseases progress, an individual’s forethought, planning, organizing, and execution of instrumental and basic activities of daily living (ADL) deteriorate and ultimately require oversight, assistance, and then performance on behalf of the patient. Without caregiver assistance, a large proportion of patients with dementia would need nursing home care earlier in the disease process, and the costs of long-term care would increase. Depression is one of the most important issues for caregivers because it is related to poor quality of life, functional decline, and even mortality. Caregiver depression is thought to be a consequence of care due to a complex interplay of factors that comprises dimensions of the patient, caregiver, and cultural background.

Characteristics of patients with dementia

Previous studies associated caregiver depression with being younger, having White or Hispanic ethnicity (compared to black ethnicity), having a lower educational level, and caring for a patient with ADL dependence[40,41], and behavioral disturbances[41,42]. There is significant evidence that BPSD influence depression in caregivers and may be more influential than the severity of cognitive deficits seen or perceived in the patient[43,44]. Different dementia types are also associated with caregiver depression. Liu et al[45] reported that the severity of patients’ BPSD and caregivers’ perceived stress contributed to the increased caregiver burden. Caregivers for patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and dementia with Lewy bodies are likely to have more caregiver burdens than those who care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Apart from cognitive and functional impairment, BPSD affect a large proportion of patients with dementia at some point in their disease course. Behavioral disturbances are highly challenging for patients with dementia, their caregivers, and their physicians, as some BPSD are difficult to manage and associated with a greater caregiver burden, higher risk for nursing home placement, prolonged hospitalization, and reduced quality of life. Huang et al[46] suggested that agitation, aggression, anxiety, nighttime behavior disturbances, irritability, and hallucinations are the five leading BPSD that are significantly related to caregiver depression. Choi et al[47] suggested that different BPSD clusters have a differential impact on caregivers’ mental health. Care providers should first distinguish between rejection of care, aggression, and agitation in patients with dementia and then manage those problematic behaviors to decrease the risk of caregiver depression.

Some studies have found anosognosia in patients with dementia to be related to caregiver burden and depression[48-50]. Anosognosia is characterized by the phenomenon of obvious unawareness, misinterpretation, or total denial of an illness. It is a common symptom of dementia[51]. One explanation is that a patient’s higher level of anosognosia results in a higher burden and depression of the caregiver. Anosognosia would increase caregivers’ social isolation and tension related to obtaining and receiving patient care[50]. Another possible explanation could be that the depression of the caregiver may distort the perceived health status of the dementia patient and possibly cause a more negative assessment of caregiver-rated dementia problems[52].

Other than the patients’ demographics, the subjective feelings of the dementia patients may also be an important topic to be studied, such as the patient’s sensation of suffering. In a longitudinal analysis[53], increases in patients’ suffering were associated with higher caregiver depression. Several studies suggest that measurable manifestations of suffering comprise (1) Physical symptoms such as chronic or acute pain, nausea, and dyspnea; (2) Psychological symptoms such as depressive symptomatology and anxiety; and (3) Spiritual well-being including inner harmony, meaning of life, and the extent to which people find comfort and strength in religious beliefs[54-56].

Characteristics of the caregivers

For dementia caregivers, factors associated with depression risk include having a low income, spending more hours caregiving (40 to 79 h/wk compared to less than 40 h/wk)[40], being female[41], having a spousal relationship[40,57], living with the patient[41,44,58], having poorer health status[44,58], and having a higher caregiver distress sensation[44,58,59]. It has been reported that approximately 80% of caregivers have some form of sleep disturbance. Poor sleep is independently associated with greater depressive symptoms[60].

Robinowitz et al[61] suggested that self-efficacy may be an important factor for recognizing caregiver depression risk. Measurements of self-efficacy in caregivers for dealing with memory decline and behavioral disturbances may be valuable to providers who may care for either or both dementia patients and caregivers. Caregiver self-efficacy relates to their conviction about his or her adaptive ability and skills to manage caregiving problems that may arise. Greater self-efficacy has been associated with better psychological and physical health outcomes in dementia caregivers, including decreased depression and anxiety[62].

It has also been suggested that social support and perceived caregiving competency are significant protective factors for caregiver depression[47].

The commitment to the caregiving role, leisure, and work was associated with the formation of guilt feelings. A higher commitment to the caregiving role has been reported to contribute to lower levels of guilt[63]. Higher levels of guilty feelings are related to lower levels of commitment to the caregiving role and to leisure and higher commitment to work. Feelings of guilt may have resulted in caregivers’ distress and depression[64].

Impact of cultural issues and values

In some regions and cultures around the globe, symptoms of dementia may be regarded as normal aging or even as a consequence of previous wrongdoing. It has also been reported that some South Asian regions tend to consider dementia an outcome of family conflict or impaired family support. On the other hand, African Americans, due in part to religious beliefs, are prone to rely more on prayer and reconstruction of difficult circumstances during challenging times. Dementia is also thought to be influenced by negative spiritual forces. Cultural factors may influence the conceptualization and help-seeking behaviors of patients with dementia and the caregivers that control their access to care. Indeed, cultural factors affect caregiver responses to the cognitive and noncognitive symptoms of dementia and the consequences of adherence or nonadherence to treatment recommendations[65].

Understanding caregiver stress has become an emerging, relevant cultural value[66]. Based on the sociocultural stress and coping model[32], Losada et al[66] explained the association between cultural values and caregiving distress. Traditional beliefs about family obligations, such as the values systems of Asian and Latino/Hispanic regions, may result in psychological strain from a greater than average emphasis on the caregiving role and the encouragement to overlook one’s own needs and feelings. When caregivers feel stress about performing duties and their personal needs are ignored, avoidant coping styles may therefore arise. Avoidant coping strategies may be the mediating factor between familial obligations and cultural values toward caregiver depression[67].

Youn et al[68] suggested that Korean and Korean American caregivers had higher levels of familism and burden than white American caregivers. It is indicated that first-generation employed caregivers appear to have less flexibility and accommodations in their work environments and are more likely to leave their positions when performing caregiving roles than second-generation caregivers. Challenges in utilizing health care systems and language barriers are also higher within the groups of first-generation caregivers[69].

Factors associated with higher rates of dementia caregiver depression, as seen in the literature review, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factors associated with increased depression in caregivers of patients with dementia in the literature

|

Dimension

|

Less modifiable factors

|

More modifiable factors

|

| Patient | Younger age, white and Hispanic ethnicity, less educational level, type of dementia (frontotemporal lobar degeneration and dementia with Lewy bodies) | More activities of daily living dependence, behavioral disturbances, higher levels of anosognosia, more physical and psychological suffering |

| Caregiver | Low income, more hours spent caregiving, female sex, spousal relationship, living with the patient, poorer health status | Higher distress sensations, sleep disturbances, lower self-efficacy, lower levels of commitment to the caregiving role, guilty feelings |

| Cultural | Familism, family obligation, language barriers | Misunderstandings, coping style, less flexibility and accommodations in their work environments |

MANAGEMENT FOR CAREGIVER DEPRESSION

Regarding dementia patients, there are few effective interventions to slow and stop the progression of cognitive impairment. However, there are many interventions designed to treat BPSD and therefore alleviate caregiver burden. Multicomponent nonpharmacological treatments, including caregiver education and support, problem solving training, and assistance in comprehending and managing specific behavioral problems, have been suggested to be effective in treating behavioral disturbances and increasing the quality of life of patients with dementia and their caregivers[70].

Numerous studies have been designed to improve depression in dementia family caregivers. We summarized types of caregiver interventions that have been classified by psychoeducation[71-77], leisure and physical activity[37,78-80], counseling[81-90], cognitive-behavioral approaches[91-94], mindfulness-based interventions[95], and psychological and social support[96-99], as shown in Table 2. We also observed and highlighted interventions utilizing telephone and technologies to deliver nonface-to-face management below.

Table 2.

Types of intervention for dementia caregiver depression in the studies

|

Type of intervention

|

Content of program

|

| Psychoeducation | Information about dementia and the different stages of dementia severity[71-73], understanding and managing behavioral problems[71,73-76], problem-solving techniques[73], coping strategies for emotional problems[73-75], communication skills[71,73-75], crisis management[73], resource information[73], targeting pain and distress (mood problems, lack of engagement in activities)[74,75,77] |

| Leisure and physical activity | Education on how to monitor time spent in leisure activities[78,79], identification of enjoyable leisure activities[78,79], prioritizing activities[79], scheduling/participating in leisure activities[79], fostering physical activity[78], individualized goal setting[78], behavioral modification skill training, behavioral activation[37,80], increasing pleasant activities[37,79] |

| Counseling | Care consultation[81-90], managing dementia symptoms[81,82,84,85,87,88], accessing community support services[81,82,86], telephone-based use of logbooks[83], information about dementia and legal issues and resources for social support[83,86] |

| Cognitive behavioral approaches | Cognitive reappraisal[91], controlling upsetting thoughts[27], enhancing self-efficacy[27,28], cognitive restructuring[92], assertive skills[92], relaxation[92], acceptance of aversive internal events and circumstances[92], choosing meaningful courses of action[92], telephone-based identification and expression of painful thoughts and emotions[93], managing painful emotions[93], accepting thoughts and emotions[93], redefinition of the relationship[92], reactivation of resources[93], adaptation to bereavement[93,94] |

| Mindfulness-based interventions | A range of practices with a focus on stress reduction, such as gentle mindful movement (awareness of the body), a body scan (to nurture awareness of the body region by region), and meditation (awareness of the breath)[95] |

| Psychological and social support | Providing information on formal social support[96,97], mutual sharing of emotions[96-98], creating an appropriate social network and home environment for the caregiver[96], support group participation[96], family role and strength rebuilding[99] |

Various interventions and key clinical content elements identified in the literature review are listed below in Table 2.

Psychoeducation

In this intervention, caregivers are educated on suitable skills to deal with caregiving requirements and stress using structured content and are often performed by small groups, including time for practice. The topics in these sessions usually comprise knowledge of dementia, learning to reserve time for self, enhancement of communication and interaction with family members, skills for managing BPSD, and related community services. More specialized topics, such as emotional management, thought and behavioral modification, and pleasant activity scheduling, may also be involved in some studies.

Leisure and physical activity

Daily pleasant experiences can create balance between “self-life” and caring for patients and help caregivers to maintain positive points of view while serving in the caregiving role. Leisure or physical activities may also serve to transform the caregivers’ negative experiences[37]. It is challenging to incorporate activities in the daily lives of caregivers for dementia patients because of their heavy workloads. Moreover, stressed individuals may diminish the skills to engage in positive interactions. The behavioral theory of depression interprets depression as a result of a series of negative reinforcements. Multiple factors create a downward spiral toward the further disruption of a healthy lifestyle and its biological rhythms and social activities, resulting in more severe depressive symptoms.

Counseling

Individual and family counseling is provided by trained providers to help caregivers manage stress and crises. This intervention is performed face to face or through telephone calls.

Psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral approaches

Psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral approaches are performed by trained health care providers to help caregivers manage stress and to treat distress and depression. These interventions are often used for caregivers with clinical depression or other significant mental health problems. They can be performed in individual or group circumstances.

Mindfulness-based interventions

In this treatment model, caregivers are trained in mindfulness and meditation strategies with the basic purpose of concentrating on the present experience nonjudgmentally. Thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are observed without being judged as good or bad with a final aim of relieving suffering. Mindfulness-based interventions are based on acceptance, receptiveness of the current situation, and establishing a balanced coexistence with personal feelings and thoughts, instead of attempting change from the beginning. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is a widely used program that involves practices with a focus on stress reduction, including gentle mindful movement (awareness of the body), a body scan (to foster awareness of the body), and meditation (awareness of the breath)[100]. Dementia not only affects the person who suffers from it but also has an impact on the patients’ caregivers. Caregivers of dementia patients are groups that experience mindfulness problems[101] and symptoms of stress and depression.

Psychological and social support

The support group is characterized by a type of mutual helping that comprises a group of people to share experiences and deal with common problems. Studies have shown that support groups can be valuable resources to the families of dementia patients, and include care information and psychological support[99]. Several studies show that caregiver support groups are able to help individuals relieve the distress of caregiving and decrease depressive symptoms[102].

We divided factors associated with caregiver depression into three dimensions: patient, caregiver, and cultural background according to the literature and matched them with the treatment plan for each factor. The appropriate treatment content corresponding to each factor is listed for reference in Table 3. However, this table needs more clinical research for validation.

Table 3.

Interventions and modifications for caregiver depression in reviewed literature, classified and matched according to the associated factors and dimensions

|

Patient with dementia

| |

| Address physical care domain | |

| Psychoeducation | |

| Counseling | |

| Environmental modification | |

| Access to community resources | |

| Relief pain | |

| Address psychological domain | |

| Psychoeducation | |

| Cognitive Behavioral approaches | |

| Strategies to treat and compensate cognitive deficits | |

| Reality and insight enhancements | |

| Address behavioral and psychological symptoms | |

| Psychoeducation | |

| Counseling | |

| Pharmacological treatments | |

| Caregiver | |

| Address distress sensation | |

| Leisure and physical activity | |

| Counseling | |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions | |

| Psychological and social support | |

| Address self-efficacy | |

| Counseling | |

| Cognitive Behavioral approaches | |

| Communication skills | |

| Behavioral management skills | |

| Problem-solving techniques | |

| Crisis management | |

| Training on nursing care | |

| Address commitment to caregiving role | |

| Counseling | |

| Psychological and social support | |

| Address guilty feelings | |

| Leisure and physical activity | |

| Counseling | |

| Cognitive Behavioral approaches | |

| Psychological and social support | |

| Address sleep problems | |

| Leisure and physical activity | |

| Cognitive Behavioral approaches | |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions | |

| Address coping strategies | |

| Psychoeducation | |

| Leisure and physical activity | |

| Counseling | |

| Psychological and social support | |

| Coping with loss and grief | |

| Address accommodations in work environment | |

| Counseling | |

| Psychological and social support | |

Key factors (listed in Table 1) considered include: (1) For patients: Activities of daily living dependence, behavioral disturbances, higher levels of anosognosia, physical, and psychological suffering; (2) For caregivers: Higher caregiver distress sensations, sleep disturbances, lower self-efficacy, lower levels of commitment to the caregiving role, guilty feelings; and (3) For cultural background: Coping style, less flexibility, and accommodations in their work environments.

DELIVERY OF TREATMENT FOR CAREGIVER DEPRESSION

Because of dementia caregiving duties or conflicts with other schedules, face-to-face interventions for caregivers are not practical in certain situations. Family caregivers may also have difficulties leaving the patient to participate in intervention activities in certain places. Furthermore, interventions for caregivers are possibly not available or difficult to participate in many communities around the world, such as rural or underdeveloped communities. Nonface-to-face interventions may also be practical in the current clinical environment with the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Telephone-based intervention

As dementia progresses, caregivers may become isolated and need a prolonged period of time to meet caregiving demands. This condition can make it difficult for them to leave their homes to seek support and resources through face-to-face interventions. To overcome these barriers, telephone-based interventions targeted to increase accessibility for caregivers are recommended. Telephone-based interventions have been demonstrated to promote the physical and mental health of caregivers[86,87]. Furthermore, telephone-based intervention is an alternative for caregivers for whom certain services are not available locally[89].

Telephone coaching also has the advantage of offering individualized recommendations for the caregiver. This is not always possible in a group setting, such as a large educational group. In some crisis situations, caregivers wanted to meet face-to-face with their instructors for suggestions. Interventions combining telephone and video have been introduced and performed[103].

Technology-driven interventions

Interventions for depression using eHealth or Connected Health (CH) largely employ information and communication technologies for caregivers. These evaluations, interventions, and treatments are performed via the internet[104]. For instance, these interventions can be provided in the form of an online course on the computer. Healthcare providers can also utilize smartphone or tablet applications designed to provide newer information and psychological support from peers as well as professionals. The care model is assisted by technology, and all the associated disciplines involved in patient care can be communicated through a health portal that offers beneficial information between formal and informal caregivers. Additionally, some programs for technology-driven interventions use technologies such as body-worn and monitoring devices. Health care professionals can help informal caregivers monitor dementia patients’ health status using these devices. The devices can provide an event alert (such as a fall or other emergency event) and facilitate communication. Technology-driven models could provide a handy and lower cost intervention compared to traditional home care, supply a family caregiver with social interaction and emotional support and facilitate information exchange with other caregivers and professionals. It could also ameliorate the decision-making process for matters about patient care[105]. The literature also suggests that dementia caregiver burden and stress could be reduced through technology-driven interventions[106]. At the same time, the self-efficacy and quality of life of caregivers will be improved by this type of intervention[105].

A study performed in Ireland[107,108] used a Connected Health Sustaining Home Stay Model for caring for patients with dementia and their caregivers. The purpose of the study was to (1) Assess the effectiveness of the platform in supporting caregivers at home; (2) Study the potential improvement of patients with dementia and their family caregivers’ mental and physical health; and (3) Investigate the platform’s usability and user experience. Another example is the system named the A Technology Platform for the Assisted Living of Dementia Elderly Individuals and their Carers[109]. It is a digital platform designed to offer support to the informal caregiver.

Case management

Patient-centered care planning is essential for case management. It includes identification and outreach, comprehensive individualized assessments, care planning, care coordination, service provisions, monitoring, evaluation and fulfilling individualized needs[110].

Due to the complexity of the symptoms of dementia, the model using a multidisciplinary approach and integrated working is beneficial in care for dementia patients. Case managers, nurses, psychiatrists, pharmacists, psychologists, occupational therapists, and social workers are all involved in decision making and supporting the caregivers living with people with dementia[111].

CONCLUSION

Overall, the prevalence of depression among dementia caregivers is higher than that seen in the general population. A structured way to study and verify associated factors and etiologies for caregivers’ depression is based on the stress coping model, which may then be expanded by adding relevant important variables. The activity restriction model in the mechanism of caregiver depression also provides an important theoretical basis for interventions and management, such as behavioral activation, leisure, and physical activities. There are many interventions used to manage caregiver depression in the literature, but after further reviewing the intervention methods, it was found that most recommended treatment plans incorporated multicomponent interventions.

The following points provide some perspective and a few suggestions to address currently unmet gaps in treatment adequacy for depression in caregivers of patients with dementia.

Understanding the clinical mechanisms of depression requires investigating psychosocial, physiological, and biological contributions. Is there a difference between depression in caregivers of dementia patients and the general population in imaging studies or in brain neuroendocrine studies? These questions need further exploration.

Most of the current research utilized psychosocial approaches. What should be further studied is whether there will be a meaningful improvement if the caregiver’s depression is also given pharmacological treatment such as antidepressants. Is there a difference in antidepressant efficacy between dementia caregivers and the general population? For individual depression symptoms, are there differences in the treatment response of these two groups?

Additionally, many current clinical studies available for review were based on cross-sectional research designs. The behavioral symptoms and daily life functions of dementia deteriorate over time. More long-term follow-up studies are needed to track whether the depressive symptoms of caregivers also change over time.

Dementia is known to occur in many different forms, each having different symptoms and disease courses. For instance, patients with vascular dementia have more obvious physical disabilities and often experience stepwise cognitive declines following each clinically diagnosed stroke event. Cognitive functioning in those with Alzheimer's disease degrades slowly, from instrumental ADL to the most basic ADL. Different types of dementia may very well have different impacts on the moods and daily lives of their caregivers.

Many clinical studies assessed the depression of caregivers by using self-rated scales or scales asking about subjective feelings as the main outcome. One such instrument is the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale[112], whose reliability and validity have been proven. Maintaining reliability and validity is best assured by objective evaluation by trained researchers. Two scales also recommended as appropriate evaluation tools are the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale[113] and the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale[114].

The clinical problems of patients with dementia are individual and unique. The author believes that the formulation and implementation of individualized treatment plans are an important component of addressing dementia caregiver depression. Therefore, the case management model for people with dementia and their caregivers needs promotion and the opportunity to evolve to meet these populations’ needs.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author has no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 31, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Article in press: November 30, 2021

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Papazafiropoulou A S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain L, Anderson C, Knifton C, Madden G. Suicide risk in informal carers of people living with dementia. Nurs Older People. 2018;30:20–25. doi: 10.7748/nop.2018.e1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greaney ML, Kunicki ZJ, Drohan MM, Ward-Ritacco CL, Riebe D, Cohen SA. Self-reported changes in physical activity, sedentary behavior, and screen time among informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1292. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery W, Goren A, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Nakamura T, Ueda K. Alzheimer's disease severity and its association with patient and caregiver quality of life in Japan: results of a community-based survey. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:141. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0831-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coehlo DP, Hooker K, Bowman S. Institutional placement of persons with dementia: what predicts occurrence and timing? J Fam Nurs. 2007;13:253–277. doi: 10.1177/1074840707300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macfarlane S, Atee M, Morris T, Whiting D, Healy M, Alford M, Cunningham C. Evaluating the Clinical Impact of National Dementia Behaviour Support Programs on Neuropsychiatric Outcomes in Australia. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:652254. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.652254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norton MC, Clark C, Fauth EB, Piercy KW, Pfister R, Green RC, Corcoran CD, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Tschanz JT. Caregiver personality predicts rate of cognitive decline in a community sample of persons with Alzheimer's disease. The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:1629–1637. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guterman EL, Allen IE, Josephson SA, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, Chiong W, Lee K, Bonasera SJ, Miller BL, Possin KL. Association between caregiver depression and emergency department use among patients with dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:1166–1173. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto N, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Shinagawa S, Ishikawa T, Mori T, Toyota Y, Matsumoto T, Adachi H, Hirono N, Tanabe H. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly people in the local community. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23:219–224. doi: 10.1159/000099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiland FJ, Kat MG, van Tilburg W, Jonker C, Dröes RM. The emotional impact of psychiatric symptoms in dementia on partner caregivers: do caregiver, patient, and situation characteristics make a difference? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:195–201. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000189035.25277.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyebode F. Sims’ symptoms in the mind: textbook of descriptive psychopathology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haley WE. The family caregiver's role in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1997;48:S25–S29. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.25s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Liu HC, Wang HC. The caregiving burden scale among Chinese caregivers of Alzheimer patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:186–191. doi: 10.1159/000017118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skaalvik MW, Norberg A, Normann K, Fjelltun AM, Asplund K. The experience of self and threats to sense of self among relatives caring for people with Alzheimer's disease. Dementia (London) 2016;15:467–480. doi: 10.1177/1471301214523438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Alberca JM, Lara JP, Berthier ML. Anxiety and depression in caregivers are associated with patient and caregiver characteristics in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41:57–69. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S, Li C, Shi Z, Wang X, Zhou Y, Liu S, Liu J, Yu T, Ji Y. Caregiver burden and prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances in Alzheimer's disease caregivers in China. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:1291–1300. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A, Ho R. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ying J, Yap P, Gandhi M, Liew TM. Validity and utility of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for detecting depression in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;47:323–334. doi: 10.1159/000500940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang SS, Lee MC, Liao YC, Wang WF, Lai TJ. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in Taiwanese elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, Ford GR, West CA, Collins RP, Isobe TL. Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:121–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polenick CA, Struble LM, Stanislawski B, Turnwald M, Broderick B, Gitlin LN, Kales HC. "The Filter is Kind of Broken": Family Caregivers' Attributions About Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuju T, Yamagami T, Yamaguchi H, Yamazaki T. Development of the Dementia Caregiver Positive Feeling Scale 21-item version (DCPFS-21) in Japan to recognise positive feelings about caregiving for people with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21:650–658. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu DSF, Cheng ST, Wang J. Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hepburn KW, Tornatore J, Center B, Ostwald SW. Dementia family caregiver training: affecting beliefs about caregiving and caregiver outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:450–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng ST, Fung HH, Chan WC, Lam LC. Short-Term Effects of a gain-focused reappraisal intervention for dementia caregivers: a double-blind cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng ST, Mak EPM, Fung HH, Kwok T, Lee DTF, Lam LCW. Benefit-finding and effect on caregiver depression: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85:521–529. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Au A, Li S, Lee K, Leung P, Pan PC, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. The Coping with Caregiving Group Program for Chinese caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease in Hong Kong. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JH, Knight BG, Longmire CV. The role of familism in stress and coping processes among African American and White dementia caregivers: effects on mental and physical health. Health Psychol. 2007;26:564–576. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: a sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight BG, Sayegh P. Cultural values and caregiving: the updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B:5–13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitrani VB, Lewis JE, Feaster DJ, Czaja SJ, Eisdorfer C, Schulz R, Szapocznik J. The role of family functioning in the stress process of dementia caregivers: a structural family framework. Gerontologist. 2006;46:97–105. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson GM, Shaffer DR. The activity restriction model of depressed affect: Antecedents and consequences of restricted normal activities. In: Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Parmelee PA, editors. Physical Illness and Depression in Older Adults: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2000: 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mausbach BT, Patterson TL, Grant I. Is depression in Alzheimer's caregivers really due to activity restriction? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2008;39:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Au A, Gallagher-Thompson D, Wong MK, Leung J, Chan WC, Chan CC, Lu HJ, Lai MK, Chan K. Behavioral activation for dementia caregivers: scheduling pleasant events and enhancing communications. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:611–619. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S72348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monin JK, Schulz R, Feeney BC, Cook TB. Attachment insecurity and perceived partner suffering as predictors of personal distress. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:1143–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz R, Savla J, Czaja SJ, Monin J. The role of compassion, suffering, and intrusive thoughts in dementia caregiver depression. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21:997–1004. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1191057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, Wood J, Sands L, Dane K, Yaffe K. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang CC, Wang WF, Li YY, Chen YA, Chen YJ, Liao YC, Jhang KM, Wu HH. Using the Apriori algorithm to explore caregivers' depression by the combination of the patients with dementia and their caregivers. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2953–2963. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S316361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiyoshi-Taniguchi K, Becker CB, Kinoshita A. What behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia affect caregiver burnout? Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:249–254. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1398797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A. The impact of the symptoms of dementia on caregivers. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:62–68. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omranifard V, Haghighizadeh E, Akouchekian S. Depression in main caregivers of dementia patients: prevalence and predictors. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:34. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.225924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu S, Liu J, Wang XD, Shi Z, Zhou Y, Li J, Yu T, Ji Y. Caregiver burden, sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in dementia caregivers: a comparison of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30:1131–1138. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217002630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang SS, Liao YC, Wang WF. Association between caregiver depression and individual behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Taiwanese patients. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2015;7:251–259. doi: 10.1111/appy.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi SSW, Budhathoki C, Gitlin LN. Impact of three dementia-related behaviors on caregiver depression: The role of rejection of care, aggression, and agitation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:966–973. doi: 10.1002/gps.5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander CM, Martyr A, Savage SA, Morris RG, Clare L. Measuring awareness in people with dementia: results of a systematic scoping review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2021;34:335–348. doi: 10.1177/0891988720924717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hallam B, Chan J, Gonzalez Costafreda S, Bhome R, Huntley J. What are the neural correlates of meta-cognition and anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease? Neurobiol Aging. 2020;94:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertrand E, Azar M, Rizvi B, Brickman AM, Huey ED, Habeck C, Landeira-Fernandez J, Mograbi DC, Cosentino S. Cortical thickness and metacognition in cognitively diverse older adults. Neuropsychology. 2018;32:700–710. doi: 10.1037/neu0000458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Migliorelli R, Tesón A, Sabe L, Petracca G, Petracchi M, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. Anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease: a study of associated factors. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:338–344. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perales J, Turró-Garriga O, Gascón-Bayarri J, Reñé-Ramírez R, Conde-Sala JL. The longitudinal association between a discrepancy measure of anosognosia in patients with dementia, caregiver burden and depression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:1133–1143. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulz R, McGinnis KA, Zhang S, Martire LM, Hebert RS, Beach SR, Zdaniuk B, Czaja SJ, Belle SH. Dementia patient suffering and caregiver depression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:170–176. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cassell EJ. Diagnosing suffering: a perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:531–534. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Black HK. Gender, religion, and the experience of suffering: a case study. J Relig Health. 2013;52:1108–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodgers BL, Cowles KV. A conceptual foundation for human suffering in nursing care and research. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1048–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, Thunell J, Zissimopoulos J. Changes in physical and mental health of Black, Hispanic, and White caregivers and non-caregivers associated with onset of spousal dementia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2020;6:e12082. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beeson R, Horton-Deutsch S, Farran C, Neundorfer M. Loneliness and depression in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21:779–806. doi: 10.1080/016128400750044279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi M, Tanaka K, Miyaoka H. Depression and associated factors of informal caregivers versus professional caregivers of demented patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beaudreau SA, Spira AP, Gray HL, Depp CA, Long J, Rothkopf M, Gallagher-Thompson D. The relationship between objectively measured sleep disturbance and dementia family caregiver distress and burden. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:159–165. doi: 10.1177/0891988708316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabinowitz YG, Mausbach BT, Gallagher-Thompson D. Self-efficacy as a moderator of the relationship between care recipient memory and behavioral problems and caregiver depression in female dementia caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:389–394. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181b6f74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steffen AM, McKibbin C, Zeiss AM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Bandura A. The revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy: reliability and validity studies. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P74–P86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.p74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gallego-Alberto L, Losada A, Márquez-González M, Romero-Moreno R, Vara C. Commitment to personal values and guilt feelings in dementia caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:57–65. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merrilees J. The impact of dementia on family caregivers: what is research teaching us? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:88. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pachana NA, Gallagher-Thompson D. The importance of attention to cultural factors in the approach to dementia care services for older persons. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:181–183. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2018.1438875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Losada A, Marquez-Gonzalez M, Knight BG, Yanguas J, Sayegh P, Romero-Moreno R. Psychosocial factors and caregivers' distress: effects of familism and dysfunctional thoughts. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:193–202. doi: 10.1080/13607860903167838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sayegh P, Knight BG. The effects of familism and cultural justification on the mental and physical health of family caregivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:3–14. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Youn G, Knight BG, Jeong HS, Benton D. Differences in familism values and caregiving outcomes among Korean, Korean American, and White American dementia caregivers. Psychol Aging. 1999;14:355–364. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu LW, McDaniel SA. Family caregiving for immigrant seniors living with heart disease and stroke: Chinese Canadian perspective. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36:1327–1345. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2015.1038346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. Targeting and managing behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: a randomized trial of a nonpharmacological intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1465–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blom MM, Zarit SH, Groot Zwaaftink RB, Cuijpers P, Pot AM. Effectiveness of an Internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kurz A, Wagenpfeil S, Hallauer J, Schneider-Schelte H, Jansen S AENEAS Study. Evaluation of a brief educational program for dementia carers: the AENEAS study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:861–869. doi: 10.1002/gps.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Villars H, Cantet C, de Peretti E, Perrin A, Soto-Martin M, Gardette V. Impact of an educational programme on Alzheimer's disease patients' quality of life: results of the randomized controlled trial THERAD. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:152. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00896-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kunik ME, Snow AL, Wilson N, Amspoker AB, Sansgiry S, Morgan RO, Ying J, Hersch G, Stanley MA. Teaching caregivers of persons with dementia to address pain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Villars H, Dupuy C, Perrin A, Vellas B, Nourhashemi F. Impact of a therapeutic educational program on quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: results of a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:167–176. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Söylemez BA, Küçükgüçlü Ö, Buckwalter KC. Application of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold Model with community-based caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;42:44–54. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20160406-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008;6:137–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2008.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Connell CM, Janevic MR. Effects of a telephone-based exercise intervention for dementia caregiving wives: a randomized controlled trial. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28:171–194. doi: 10.1177/0733464808326951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gitlin LN, Arthur P, Piersol C, Hessels V, Wu SS, Dai Y, Mann WC. Targeting behavioral symptoms and functional decline in dementia: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:339–345. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moore RC, Chattillion EA, Ceglowski J, Ho J, von Känel R, Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Patterson TL, Grant I, Mausbach BT. A randomized clinical trial of Behavioral Activation (BA) therapy for improving psychological and physical health in dementia caregivers: results of the Pleasant Events Program (PEP) Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steffen AM, Gant JR. A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:195–203. doi: 10.1002/gps.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holmes SB, Adler D. Dementia care: critical interactions among primary care physicians, patients and caregivers. Prim Care. 2005;32:671–682, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joling KJ, van Marwijk HW, Smit F, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, van de Ven PM, Mittelman MS, van Hout HP. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? PLoS One. 2012;7:e30936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phung KT, Waldorff FB, Buss DV, Eckermann A, Keiding N, Rishøj S, Siersma V, Sørensen J, Søgaard R, Sørensen LV, Vogel A, Waldemar G. A three-year follow-up on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for patients with mild dementia and their caregivers: the multicentre, rater-blinded, randomised Danish Alzheimer Intervention Study (DAISY) BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003584. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kuo LM, Huang HL, Liang J, Kwok YT, Hsu WC, Su PL, Shyu YL. A randomized controlled trial of a home-based training programme to decrease depression in family caregivers of persons with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:585–598. doi: 10.1111/jan.13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kuo LM, Huang HL, Liang J, Kwok YT, Hsu WC, Liu CY, Shyu YL. Trajectories of health-related quality of life among family caregivers of individuals with dementia: A home-based caregiver-training program matters. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jackson D, Roberts G, Wu ML, Ford R, Doyle C. A systematic review of the effect of telephone, internet or combined support for carers of people living with Alzheimer's, vascular or mixed dementia in the community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:218–236. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tremont G, Davis JD, Bishop DS, Fortinsky RH. Telephone-delivered psychosocial intervention reduces burden in dementia caregivers. Dementia (London) 2008;7:503–520. doi: 10.1177/1471301208096632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.González-Fraile E, Ballesteros J, Rueda JR, Santos-Zorrozúa B, Solà I, McCleery J. Remotely delivered information, training and support for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1:CD006440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006440.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tremont G, Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, Ott BR, Fortinsky RH, Gozalo P, Yue MS, Bryant K, Grover C, Bishop DS. Psychosocial telephone intervention for dementia caregivers: A randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Au A, Yip HM, Lai S, Ngai S, Cheng ST, Losada A, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. Telephone-based behavioral activation intervention for dementia family caregivers: Outcomes and mediation effect of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:2049–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Losada A, Márquez-González M, Romero-Moreno R, Mausbach BT, López J, Fernández-Fernández V, Nogales-González C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for dementia family caregivers with significant depressive symptoms: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:760–772. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meichsner F, Schinköthe D, Wilz G. Managing loss and change: grief interventions for dementia caregivers in a CBT-based trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:231–240. doi: 10.1177/1533317515602085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lopez L, Vázquez FL, Torres ÁJ, Otero P, Blanco V, Díaz O, Páramo M. Long-term effects of a cognitive behavioral conference call intervention on depression in non-professional caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kor PPK, Liu JYW, Chien WT. Effects of a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;98:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chien WT, Lee IY. Randomized controlled trial of a dementia care programme for families of home-resided older people with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:774–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chu H, Yang CY, Liao YH, Chang LI, Chen CH, Lin CC, Chou KR. The effects of a support group on dementia caregivers' burden and depression. J Aging Health. 2011;23:228–241. doi: 10.1177/0898264310381522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dröes RM, van Rijn A, Rus E, Dacier S, Meiland F. Utilization, effect, and benefit of the individualized Meeting Centers Support Program for people with dementia and caregivers. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1527–1553. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S212852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fung WY, Chien WT. The effectiveness of a mutual support group for family caregivers of a relative with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2002;16:134–144. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2002.32951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Danucalov MA, Kozasa EH, Afonso RF, Galduroz JC, Leite JR. Yoga and compassion meditation program improve quality of life and self-compassion in family caregivers of Alzheimer's disease patients: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:85–91. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kaasalainen S, Craig D, Wells D. Impact of the Caring for Aging Relatives Group program: an evaluation. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Graven LJ, Glueckauf RL, Regal RA, Merbitz NK, Lustria MLA, James BA. Telehealth Interventions for Family Caregivers of Persons with Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Telemed Appl. 2021;2021:3518050. doi: 10.1155/2021/3518050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Christie HL, Bartels SL, Boots LMM, Tange HJ, Verhey FJJ, de Vugt ME. A systematic review on the implementation of eHealth interventions for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Internet Interv. 2018;13:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Godwin KM, Mills WL, Anderson JA, Kunik ME. Technology-driven interventions for caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:216–222. doi: 10.1177/1533317513481091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bossen AL, Kim H, Williams KN, Steinhoff AE, Strieker M. Emerging roles for telemedicine and smart technologies in dementia care. Smart Homecare Technol Telehealth. 2015;3:49–57. doi: 10.2147/SHTT.S59500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guisado-Fernandez E, Blake C, Mackey L, Silva PA, Power D, O'Shea D, Caulfield B. A smart health platform for measuring health and well-being improvement in people with dementia and their informal caregivers: usability study. JMIR Aging. 2020;3:e15600. doi: 10.2196/15600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guisado-Fernandez E, Caulfield B, Silva PA, Mackey L, Singleton D, Leahy D, Dossot S, Power D, O'Shea D, Blake C. Development of a caregivers' support platform (Connected Health Sustaining Home Stay in Dementia): protocol for a longitudinal observational mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8:13280. doi: 10.2196/13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Torkamani M, McDonald L, Saez Aguayo I, Kanios C, Katsanou MN, Madeley L, Limousin PD, Lees AJ, Haritou M, Jahanshahi M ALADDIN Collaborative Group. A randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate a technology platform for the assisted living of people with dementia and their carers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:515–523. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sandberg M, Jakobsson U, Midlöv P, Kristensson J. Case management for frail older people - a qualitative study of receivers' and providers' experiences of a complex intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Grand JH, Caspar S, Macdonald SW. Clinical features and multidisciplinary approaches to dementia care. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:125–147. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S17773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Carleton RN, Thibodeau MA, Teale MJ, Welch PG, Abrams MP, Robinson T, Asmundson GJ. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: a review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]