Abstract

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), and its clinical manifestation that is calcific aortic valve stenosis, is the leading cause for valve disease within the developed world, with no current pharmacological treatment available to delay or halt its progression. Characterized by progressive fibrotic remodelling and subsequent pathogenic mineralization of the valve leaflets, valve disease affects 2.5% of the western population, thus highlighting the need for urgent intervention. Whilst the pathobiology of valve disease is complex, involving genetic factors, lipid infiltration, and oxidative damage, the immune system is now being accepted to play a crucial role in pathogenesis and disease continuation. No longer considered a passive degenerative disease, CAVD is understood to be an active inflammatory process, involving a multitude of pro-inflammatory mechanisms, with both the adaptive and the innate immune system underpinning these complex mechanisms. Within the valve, 15% of cells evolve from haemopoietic origin, and this number greatly expands following inflammation, as macrophages, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and innate immune cells infiltrate the valve, promoting further inflammation. Whether chronic immune infiltration or pathogenic clonal expansion of immune cells within the valve or a combination of the two is responsible for disease progression, it is clear that greater understanding of the immune systems role in valve disease is required to inform future treatment strategies for control of CAVD development.

Keywords: Calcific aortic valve, disease, Inflammation, Immunity, Calcification, Clonal, haematopoiesis

This article is part of the Spotlight Issue on Cardiovascular Immunology.

1. Introduction

Heart valve disease, encompassing a number of common cardiovascular conditions, is estimated to be prevalent in 2.5% of the western population,1 accounting for 10–20% of all cardiac surgical procedures in the USA.2 Manifestations of valvular heart disease are broad and skew in prevalence towards an ageing population. Calcific aortic valve sclerosis is the subclinical form to calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), in which stenosis occurs within the thickening valve, steadily reducing its haemodynamic capacity and severely impacting the movement of blood through the aorta. Following development of severe symptomatic CAVD prognosis becomes increasingly worse, with surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement critical to a positive patient outcome. The 1-year mortality rates among patients with untreated severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, defined as aortic valve area <1 cm2, nears 50%,3 and with prevalence predicted to double within the next half century, a complete understanding of risk factors and biological inference is imperative for the improvement of patient outcomes and care. With no current pharmacological interventions available to prevent or treat CAVD, the unmet clinical burden continues to rise, underscoring the crucial requirement for greater clinical understanding and drug development.

2. Molecular development and risk factors of valve disease

Once considered a purely degenerative pathology, CAVD progression is now believed to be an active cellular process occurring within the aortic valve leaflets.4,5 Loosely similar to the development of atherosclerosis, once the endothelium becomes activated due to a variety of insults, quiescent resident tissue cells, valvular interstitial cells (VICs) in the case of aortic valves, and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) within vessels undergo osteogenic-like changes and deposit a hydroxyapatite matrix within the tissue, which acts as a catalyst for further progression of calcification and inflammation.5,6 This progressive pathophysiological process culminates in the fibrosis, calcification, and eventual haemodynamic obstruction of the valve, requiring intervention. Upon closer immunohistochemical investigation, lipid infiltration is prevalent within the diseased valve extracellular matrix,7 with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) undergoing oxidation to oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), which is recognized via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on VICs, valvular endothelial cells (VECs), and macrophages, propagating inflammation. Moreover, the accumulation of macrophages to the valve starts an inflammatory cascade, increasing immune infiltration and disease progression. Of note, however, whilst lipid laden macrophages promote atheroma formation in the vessels, within the valve lipids are retained in the relatively acellular collagenous tissue, evidenced by the stark difference in response to statins. Unique risk factors and biological insight from valve-focused research suggest that While traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as age, sex, hypertension, smoking, high LDL levels, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, contribute to CAVD development,8 other risk factors such as lipoprotein(a) may be associated with more rapid progression of CAVD.5 Moreover, biomechanical stress is known to play a significant role in both the initiation and progression of CAVD, particularly in individuals presenting with a bicuspid aortic valve morphology, which results in a greater level of mechanical stress on the valve, constituting almost half of patients undergoing surgery, despite a prevalence of <2% in the general population.9 Similarly, patients with chronic or end-stage kidney disease and other systemic disorders of calcium and phosphate regulation are particularly susceptible to accelerated CAVD development.

3. Rheumatic heart valve disease vs. calcific aortic valve disease

Whilst CAVD is the most common cause of aortic stenosis in the western world, rheumatic heart valve disease (RHVD) caused by streptococcal infection remains prevalent in the developing world, with 250 000 deaths attributed yearly worldwide, predominantly in young people.10 RHVD stems from an abnormal auto-immune response termed ‘molecular mimicry’, to group A streptococcal infection in a genetically susceptible host. Firstly manifesting as an acute rheumatoid fever before the production of auto-antibodies targets the endocardial structures, leading to irreversible mitral and rarely aortic valve damage and heart failure. Penicillin has been shown to be an effective way to prevent the disease, coupled with anti-inflammatory drugs to low inflammation and reduce the risk of heart damage; however, long-term treatment in low-mid-income countries is often challenging and recurrent infections are common.11 Although the aetiology of RHVD and CAVD remains distinct, recent similarities have been drawn between the inflammatory nature of both pathologies, and as the immune response in CAVD takes centre stage in researchers attempt to further understand this devastating pathology, the lessons learned from RHVD should not be overlooked.

With the underlying pathophysiology and the role of immunity of CAVD still not well understood, it is imperative that future work linking both the adaptive and innate immune systems (Table 1) with disease progression is be conducted to further delineate this currently untreatable pathology. Thus, this review will draw from the considerably more investigated roles of immune cells within atherosclerosis with the hypothesis that this may be a good starting point for beginning to unpick the complicated role of the immune system in CAVD.

Table 1.

Immune cells identified in calcific aortic valve disease and atherosclerosis

| Cell type | Immunological role | Role in CAVD | Role in atherosclerosis | Markers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils |

Innate immune cell; phagocytosis; formation of NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps); release of granules and radical species Recruiting and activation of macrophages and platelets factors |

Most prevalent within CAVD, ratio between neutrophils and lymphocytes associated with CAVD severity. Activated by elevated lipid levels and promote VEC dysfunction in the valve | 52 , 56 | Pro-atherogenic; neutrophil presence correlates with rupture prone plaque and neutrophil protease accumulation promotes plaque instability | 55 , 177 |

|

| Basophils | Innate immune cell; releases histamine, contributes to chronic allergic responses | Function unknown | Basophil count associated with atherosclerosis progression and worse outcome, role unclear | 178 , 179 |

|

|

| Eosinophils | Innate immune response; involved in parasitic defence, asthma, and allergic reactions | Elevated in peripheral blood count, no direct function known | 180 | Pro-atherogenic; activated eosinophils promote plaque instability and thrombi formation and positively correlate with worse CVD outcomes | 181–183 |

|

| Mast cells | Innate immune cell; mediates hypersensitivity and allergic reactions via binding IgE and releasing histamine. May regulate blood flow and coagulation | Increased in bicuspid aortic valve, function unknown | 59 , 63 , 64 , 98 | Activated mast cells promote atherosclerosis progression, matrix degradation apoptosis and recruitment of pro-inflammatory cells | 184–186 |

|

|

Natural killer cells (NKTs) |

Innate immune cell; cytotoxic lymphocyte which induces a rapid response to viruses and intracellular pathogens and tumour formation | Associated with valvular pressure gradients and disease severity, few studies undertaken in NKT in valve | 139 , 140 | Pro-atherogenic; promotes Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines and drives inflammation through INFγ and MMP production, may promote apoptosis of plaque cells | 187–189 |

|

| Monocyte | A non-differentiated cell within the peripheral blood; may differentiate into tissue resident macrophages and dendritic cells | Recruited into the valve by VEC expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 where they differentiate to macrophages | 73 , 190 | Increased in response to hyperlipidemia; recruited into early lesions where they differentiate into pro-inflammatory macrophages | 70 |

|

| Pro-inflammatory M1 Macrophage |

APC; Phagocytose pathogens, antigen presentation Initiate inflammatory and cytotoxic immune response |

Increased in CAVD and may promote osteogenic calcification | 80 , 107 , 191 , 192 | Hallmark of plaque development, promotes local inflammation, thrombosis, and plaque destabilization. Accumulated lipids may differentiate into foam cells | 76 , 84 , 88 , 193 |

|

| Anti-inflammatory M2 Macrophage | Antigen presenting cell; phagocytotic with a role in tolerogenic and profibrotic responses | Decreased in CAVD, role unknown | 191 , 194 | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; promotes early-stage atherosclerosis and may accumulate small amounts of lipids, undergo apoptosis in the presence of oxLDL | 76 , 195 |

|

| Dendritic cells | Antigen presenting cell; induces both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses | Present in healthy valves, unknown process in CAVD, may activate Th1 response | 67 | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; identified within the vascular wall, may differentiate into foam cells and produce metabolize lipids. Role in Treg homoeostasis and inflammation resolution | 196–198 |

|

| Th1 T cell | Adaptive immune cell; targets intracellular and extracellular bacteria and fungi, activates macrophages and cytotoxic T cells | Th1 cytokines IFNα and IL-1b found in CAVD, no cellular presence described | 38 , 120 , 122 | Proatherogenic; Th1 population enriched in plaques, INFγ promotes plaque instability and may accelerate inflammatory response | 105 , 118 , 120 |

|

| Th2 T cell | Adaptive immune cell; targets helminth infections and extracellular parasites, provides help for B cells to IgE production, activates eosinophils and mast cells | Th2 cytokine IL-33 found in CAVD, no cellular presence described | 110 | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; higher Th2 cell number correlates with lower subclinical burden. Function unclear | 118 , 120 |

|

| Th9 T cell | Adaptive immune cell; targets helminth infections, allergic responses, autoimmunity, and tumour suppression | Function unknown. | Proatherogenic; Increase IL-17 and VCAM-1 expression, decrease monocyte infiltration within the plaque, and function in the plaque unknown | 118–120 | IL-9 | |

| Th17 T cell | Adaptive immune cell; targets extracellular bacteria. enhances neutrophil response and may improve epithelial barrier function | Th17 cytokine IL-17 found in CAVD, IL-17 correlates with disease progression, no cellular presence described | 115 | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; peripheral Th17 population increases in unstable CVD, with IL-17 and INFγ promoting smooth muscle inflammation | 113 , 118 , 120 , 122 |

|

| Th22 T cell | Adaptive immune cell; suggested to promote repair of damaged epithelial barriers and enhances response against some pathogens | Function unknown | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; promotes plaque growth and stabilization, IL-22 higher in symptomatic atherosclerosis compared to asymptomatic patients | 118–120 |

|

|

|

T follicular helper cell (Tfh) |

Adaptive immune cell; role in germinal centre formation, B-cell antibody isotype switching and antibody affinity maturation. Enables B cells to develop into plasma cells for longer term immunity | Function unknown | Pro-atherogenic; can be regulated by regulatory subset of CD8+, function unclear | 129 , 199 |

|

|

|

CD28null CD4+ T cell |

adaptive immune cell; releases inflammatory and cytotoxic molecules that promote tissue damage and inflammation | CD28null CD4+ cytokines INFγ and TNFα found in the valve, no cellular presence described | 155 | Pro-atherogenic; increase endothelial and smooth muscle apoptosis, highly prevalent in plaques | 118 , 200–202 |

|

| γδ T cell | Adaptive immune cell; small subset of T cells with immunosuppressive function on lymphocytes. Promotes tissue repair, tolerance, and cell healing | Function unknown | May modulate atherosclerosis, few studies on γδ T cells in atherosclerosis | 200 , 141 |

|

|

|

T regulatory cell (Treg) |

Adaptive immune cell; resolves inflammation and supresses both CD4+ and CD8+ responses | Tregs increased in CAVD, Treg cytokines IL-10 inversely correlates with calcium within the valve. Function unknown | 49 , 145,146 | Atheroprotective; promotes plaque stabilization | 118 , 147,148 |

|

| CD8+ T cell | Adaptive immune cell; kills infected or tumour cells and intracellular pathogens | CD8+ T-cell cytokine INFγ promotes stenosis and impairs osteoclast function within the valve | 93 , 154 , 155 | Proatherogenic; abundant in atherosclerotic plaque, predominantly in the fibrous cap and possible clonal expansion within the plaque | 203–205 |

|

| B Cell | Adaptive immune cell; produces antibodies and may differentiate into plasmablast following antigen activation | B-cell presence correlates with macrophages within the valve and increase with valve calcification and transvalvular gradient | 140 , 161 | Pro- and anti-atherogenic; recognizes neo-self-epitopes present on LDL and apoptotic cells and produces both oxidation-specific epitopes to limit disease and pathogenic IgE | 157 , 159 |

|

4. Initiation of valve disease

4.1 Resident valve cells

Understanding the impact of immune signalling within the valve is only useful when considering the composition of a healthy valve. Differentiated from the cardiac neural crest and the embryonic secondary heart field, respectively, VECs and VICs maintain homoeostasis within the collagenous valves, nested within the fibrotic aortic ring. A fraction of a millimetre-thick, aortic valve leaflets are composed of a dense extracellular matrix, often delineated into three layers: fibrosa, spongiosa, and ventricularis.

4.1.1 Valvular endothelial cells

The endothelium, which lines the heart valve cusps, is integral to maintaining valvular homoeostasis through the continuance of tight junctions that serve to limit influx of foreign cells and particles into the valve. Due to the constant movement of the leaflets, VECs experience a wide array of forces, many of which translate to biological stress responses within the tissue.6,12,13 These haemodynamic signals contribute to phenotypic changes within the endothelium, and transduction of these signals through VECs to the underlying VICs has been directly linked to the onset and progression of CAVD14 (Figure 1). Although significantly less studied than their interstitial counterparts, VECs are essential in maintaining VIC quiescence through inhibition of proliferation and myofibroblastic activation through shear-stress-related pathways, suggested to work in tandem to modulate calcification and maintain valvular homoeostasis.15,16 Systemic endothelial dysfunction, present within the early stages of valve disease, is attributed in part to the reduction in haemodynamic sheer stress against the endothelium on the aortic side of the valve.17,18 Calcification predominantly occurs on the fibrosa side of the valve,19 where disturbed flow is apparent. Valvular endothelium has the unique ability to undergo endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), which is critical during valvulogenesis20 and contributes to calcification.21,22 Notably, VECs within adult valves can also undergo EndMT and contribute to the replenishment of VICs and remodelling of the valve leaflets.23 Current research suggests that this process is TGFβ-dependent through an NFκB-mediated inflammatory pathway,24 triggered in part by the oscillatory stress dominating in CAVD. With the phenotype of the endothelium disturbed, the VECs become activated, thus allowing for both the sub-endothelial infiltration of lipids and the increase in immune infiltrates driven predominantly by trans-endothelial migration of macrophages and T cells. The additive impact of the assault on the valves leads to the progression of early lesions, causing increased mineralization in a positive feedback cycle of damage, and ultimately resulting in valvular remodelling.

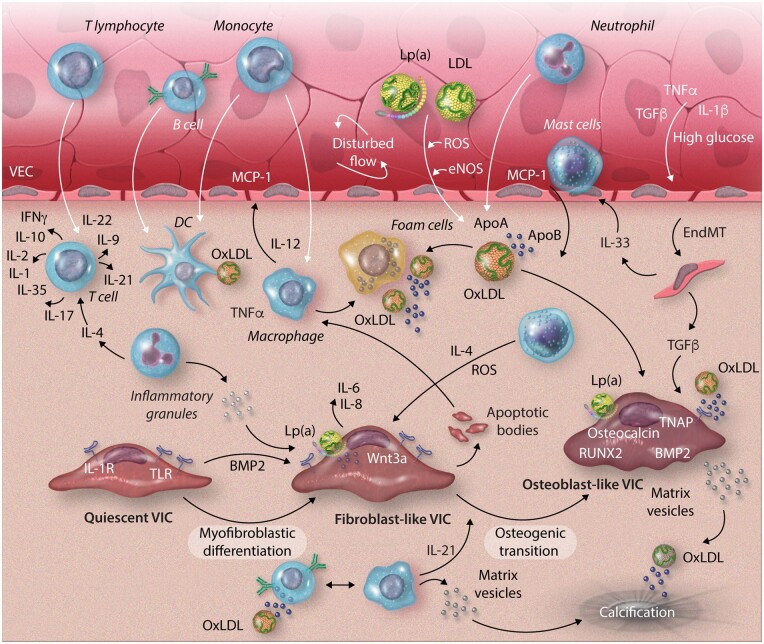

Figure 1.

Complex immune cell networks play a crucial role in valvular calcification. VECs under disturbed flow express adhesion molecules, allowing immune cells to infiltrate the valve. Adaptive immune cells, T lymphocytes and B cells, infiltrate the valve through the damaged endothelium. T-cell differentiation then differentiates and expresses both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines depending on the T-cell subtype. B cells respond to oxidized lipid particles (oxLDL) through interaction with antigen-presenting cells (APC) and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and antibodies. Innate immune cells, mast cells and neutrophils, enter the valve and produce inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and cytotoxic granules, promoting cellular apoptosis and inflammation. APCs, dendritic cells and macrophages, differentiate within the tissue from circulating monocytes. Both present lipid and apoptotic body antigens to the adaptive immune cells, promoting adaptive immune cell response and proliferation. ApoA/B, apolipoprotein A/B; BMP2, bone morphogenic protein-2; DC, dendritic cell; EndMT, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide; IFNγ, interferon gamma; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor-2; TGFβ, tumour growth factor-beta; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNAP, tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; VECs, valvular endothelial cell; VIC, valvular interstitial cell.

4.1.2 Valvular interstitial cells

The majority of the cellular population within the healthy valve consists of VICs. Derived from the VECs and the cardiac neural crest, VICs are fibroblast like cells and serve as the primary source of calcification during valvular disease. Following initiation of calcification through endothelial dysfunction, TLRs, namely TLR2 and TLR4, present on VICs are upregulated.25,26 Stimulation of these receptors via lipid infiltration and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) produced through tissue damage in the valve triggers the NFκB pathway, resulting in production of a multitude of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-6, IL-8, and ICAM-1.27–29 Moreover, TLR signalling promotes bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) and Runx2 production, both of which are crucial in the development of calcification of the valve.27 Similar to smooth muscle cells within atherosclerotic-driven vascular calcification, prolonged injury by pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads to increased DNA damage,30,31 promoting changes to a calcific phenotype, thus progressing calcific disease. Unresolved DNA damage within the VICs leads to apoptosis leading to DAMP production within the valve. DAMPs then subsequently phagocytosed and processed by antigen-presenting cells and presented to the T cells, perpetuating an inflammatory environment.31

4.2 Lipid regulation with the valve

Lipid accumulation within the valve is now understood to be of the key players in valve disease development, with both LDL cholesterol and Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels demonstrated as risk factors for CAVD and accelerated disease progression.32 Notably, while a role for elevated plasma levels of LDL and Lp(a) within atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease has been well studied, the role of lipids within aortic stenosis and valve is less well understood. Seminal studies have suggested patients with high levels of oxLDL have denser inflammatory infiltrates, increased vascular remodelling, and higher levels of inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1ß), highlighting the impactful role of lipids in CAVD.33 Moreover, both observation and genomic studies have provided strong evidence for a casual role in elevated Lp(a) levels in CAVD, suggesting a multitude of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the LPA locus increase the risk of valve disease.34 Both Lp(a) and oxLDL carry oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) within the circulation, known to be a major inflammatory catalyst. Reduction in endothelial integrity allows for the subendothelial accumulation of lipids, which subsequently undergoes extensive oxidative modification and stimulates production of monocyte-specific chemoattractants such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1).35 Moreover, the increased generation of ROS due to sustained endothelial injury works as a positive feedback loop to promote excessive inflammatory mediator generation, reducing the endothelial barrier function further and allowing greater dysregulation within the valve. Lipids are then able to accumulate within the extracellular matrix space, with ApoC-III recently implicated as an active and modifiable driver of CAVD.7 Whilst most of the available oxidized lipids enter the vasculature at a cellular level, oxLDL can also exit the subendothelial space and enter the circulation. The presence of circulating oxLDL provides ample immunogenic epitopes that, when presented, can activate T lymphocytes, which in turn expand and move to target more lipids within the valve, further promoting immune infiltration in the valvular leaflets, targeting lipid-laden VICs, VECs, and macrophages.

4.3 Cytokines signalling in valve disease

Cytokines play an essential role in inflammatory-mediated disease, with recent work highlighting the intricacies and interconnectivity of the immune system and the resident valve cells.36 Unsurprisingly, CAVD and RHVD are similar cytokine and proteomic profiles as hypercholesterolaemia, myocardial infarction, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), all of which involve auto-antibodies and cellular-associated antigens, suggesting a significant role for the adaptive immunity in these inflammatory pathologies.37,38 Notably, however, RHVD is the result of an autoimmune response to an infection and thus results in greater levels of inflammatory cytokines when compared to CAVD, the signature remains comparable.39 Acute phase reactants, the first phase of cytokines released during CAVD development, serve to activate and recruit immune cells to the local area. TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 are all crucial acute phase reactants and are all significantly increased in CAVD, with loss of function mutations in the IL-6 receptor associated with decreased severity of aortic stenosis.40 TNFα, a pleiotropic cytokine, promotes CAVD in a multitude of ways. Shown to reduce levels in an HDL rich valve, aberrant TNFα signalling promotes calcium absorption within VICs and adhesion molecule expression in VECs, resulting in increased calcification and the recruitment of pro-atherogenic immune cells and the initiation of the inflammatory cascade within the valve.41,42 The activation of the acute cytokines at the onset of CAVD gives evidence to the role of the adaptive immune system, but with great redundancy between the cytokines producing cells and activation it still remains unclear which immune cells act as the catalyst for the development of valve disease. One such cytokine, which is produced and activates a multitude of cells within the immune system, is TGFβ, with its role in both pro- and anti-calcification processes highlighted in recent years. Often implicated in myofibroblastic transition of VICs to a de-differentiated state before mineralization, its concurrence with dendritic cell (DC) activation, which primes both inflammatory and immunomodulatory T cells, again highlights the role of leucocytes in the early-stage development of CAVD.43 Similarly, IL-6 has been implicated as a driving force in both pro-inflammatory T-cell maturation44 and valve calcification,45 with IL-6 silencing shown to inhibit mineralization in vitro.46 As expected, cytokines deemed pro-inflammatory are also shown to promote calcification within VICs. IL-1β promotes matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) expression,47 both of which promote osteogenic differentiation of VICs and production of inflammatory mediators through the NF-kB axis. Further evidence of the osteogenic role of IL-1 is suggested with IL-1 receptor agonist (IL-1RA), an important anti-inflammatory receptor agonist, with IL-1RA deficiencies suggested to significantly modulate the progression of aortic valve disease.48 Conversely, a number of cytokines have been demonstrated to suppress calcification. Circulating IL-10 inversely correlates with calcium formation in the aortic valve49; however, the mechanism remains unknown. Within RHVD, the role of IL-10 is more apparent.37 IL-10 is significantly elevated in chronic RHVD patients, suggesting an ill-fated attempt by Treg cells to dampen down immunogenic responses. Mutations and presence of IL-10 are suggested to predict the severity of RHVD,50 further highlighting the divergent immune profile between non-rheumatic and rheumatic valve diseases. VICs, through TLR signalling, have been shown to reduce valve mineralization when treated with IL-37.25,51 Produced by natural killer T cells, activated B cells, and monocytes, IL-37 was demonstrated to suppress oxLDL-driven calcification, inhibiting NFκB and ERK1/2, thus suggesting a possible area of treatment through immunomodulation. Immunomodulation has been already applied to the field of cancer, but yet to see fruition in valvular disease. The capacity of cytokines to both promote and suppress valvular disease progression illustrates the complex and often critical role inflammation can play within CAVD, and it is only through precise mechanistic understanding that immunity may be used to better manage valve disease.

5. Innate immunity in the progression of valve disease

5.1 Inflammatory first defence

Driven by inflammation and yet often not considered a chronic inflammatory condition, CAVD can be characterized by non-resolving inflammation within the valve. Innate immunity, the first line of defence against both sterile and pathogen infections, can trigger the amplification of inflammation within the valve leaflets, promoting adaptive immune infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression in both immune and resident cell populations.

5.1.1 Neutrophils

Comprised of neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils, granulocytes are often included in the acute phase of inflammation, occurring soon after the inflammatory reaction, in response to pro-inflammatory signals. The most abundant effector cell within the innate immune system, neutrophils are armed with a broad arsenal of pro-inflammatory molecules potentially harmful to host tissue, suggesting a specific in aortic valve disease. Within CAVD patients, neutrophils are the prevailing circulating granulocytes, proven critical to the initial immune response to injury, and the ratio between neutrophils and lymphocytes has proven to be associated with the severity of CAVD.52 However, due to their relatively short lifespan and difficultly in isolating, neutrophils remain understudied in valve disease. Elevated lipid levels activate neutrophils, which secrete free radial species and granules, further inducing endothelial dysfunction and allowing for increased immune infiltration into the valve.53 Neutrophils produce a broad range of cytokines which are notably hard to attribute directly to neutrophils, including but not limited to, colony stimulatory factors (G-CSF, GM-CST, IL-3), anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1RA, IL-4, TGFb1, TGFb2), immunoregulatory cytokines (INFα, IFNβ, IFNγ, IL-21, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27), pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-16, IL-17, IL-18), members of the TNF-superfamily (TNFα, FasL, CD30L, TRAIL, APRIL, CD40L, RANKL), and angiogenic and fibrotic factors (VEGF, BV8, HBEGF, FGF2, TGFα).54 Additionally, it has been shown that neutrophil-derived cytokines could increase expression of cell adhesion molecules, thus suggesting a role for neutrophils in recruiting and activating macrophages and subsequently polarizing them to a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Intriguingly, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which have been associated with atherosclerotic development through the breakdown of the extracellular matrix and increased endothelial dysfunction, are now also linked to aortic stenosis progression.55 Following migration, neutrophils release histone and neutrophilic enzyme containing NETs, which contribute to the thickening of the intima in vessels and promote pathogenic inflammation. In the case of aortic stenosis, NETs are present within aortic valve leaflets, accounting for 25% of total endothelium and sub-endothelium cell number, leading to increased endothelial permeability and activation of the coagulation cascade through platelet recruitment, enhancing the inflammatory process.56 Further work is needed to fully elucidate the cross-talk between NETs and fibro-calcific development within the valve. However, the involvement of neutrophils in disease pathogenesis is an exciting area for further investigation.

5.1.2 Basophils

Accounting for <1% of the granulocyte population, basophils have little known roles in atherosclerosis, CAVD or RHVD. Recent association of the total basophil cell count has been linked with an increased risk of mortality in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).57

5.1.3 Eosinophils

Often associated with asthma,58 eosinophils have yet to be identified in CAVD. Eosinophil-related chemokine CCL11 has been shown to be present within the valve, suggesting they may be recruited in; however, positive identification of eosinophils within the valve is required to move forward with delineating their role. To note, Th2 cytokine, IL-33, which plays influential role in both homoeostatic eosinophil development and activation during disease, has been identified as a marker of CAVD, underscoring the need to further investigate the innate-adaptive axis in CAVD.

5.1.4 Mast cells

CD117+ mast cells, characterized by a monolobular nucleus and containing numerous cytoplasmic granules, have been identified as part of the polymorphous cellular infiltrate present in all layers of valvular tissue.59 Producing a multitude of pro-angiogenic, pro-inflammatory, and anti-inflammatory cytokines, mast cells are widely distributed within all vascularized tissues, and their activation and subsequent degranulation have been implicated in acute coronary syndromes (ACSs) and myocardial infarction pathogenesis.60 Furthermore, mast cell secretion of chymase converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which has been demonstrated to promote valvular thickening in mice.61,62 Within aortic stenosis, correlation between mast cell prevalence and increase in osseous metaplasia was seen within the valve.63 Significantly greater numbers of mast cell were reported in bicuspid valves compared to tricuspid, unsurprisingly, given the inflammatory nature and severity of bicuspid aortic valve disease.64 With mast cells associated with severity of aortic stenosis, restriction in leaflet motion, and calcification development, it could be suggested that inhibition of mast cell degranulation may limit the inflammatory response within valve disease65; however, more research must be done before conclusions can be drawn.

5.2 Antigen-presenting cells and immunological priming

Antigen-presenting cells play a crucial role in both defining the innate immune response and promoting the adaptive immune response. Present in the healthy valve tissue, resident macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) are enriched within CAVD and their presence can be correlated with disease progression and severity, most described in atherosclerosis and less in valves,66,67 making them an exciting avenue for CAVD research.

5.2.1 Monocytes

The mononuclear phagocytic cells, blood monocytes, and tissue macrophages follow a well-defined line of development, through committed progenitor cells to highly specialized cardiac macrophages resident within the valves (Figure 2). Monocytes are defined as short-lived circulating cells, which may differentiate into both DCs and macrophages following engagement within inflammatory markers. Classified as classical: CD14hiCD16null, intermediate: CD14hiCD16+, and non-classic monocytes: CD14lowCD16hi, these three subtypes play significantly different roles within the inflammatory response.68 Classical monocytes are heavily implicated in inflammation and comprise over 90% of circulating monocytes. Upon extravasation, classical monocytes release TNFα and produce limited amounts of nitric oxide,69 both of which promote inflammation, before predominantly differentiating into DCs and presenting antigens to T cells in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II dependent manner. In contrast, non-classical monocytes constitutively produce IL-1RA and promote a wound-healing phenotype, differentiating mainly into macrophages, which surveil the endothelium.70 Finally, intermediate monocytes produce the greatest amount of ROS and have significantly greater inflammatory properties than the two other subtypes. Following a chronic inflammatory event, intermediate monocytes expand their population from almost undetectable to about 8% of circulating blood monocytes, in cases such as myocardial infarction and heart failure,71,72 and are also present in patients with severe calcific aortic valve stenosis.73 However, whether monocytes are present in the valve due to chemokine attraction to severe inflammation or play a more central role in the induction of CAVD-driven inflammation remains to be determined.

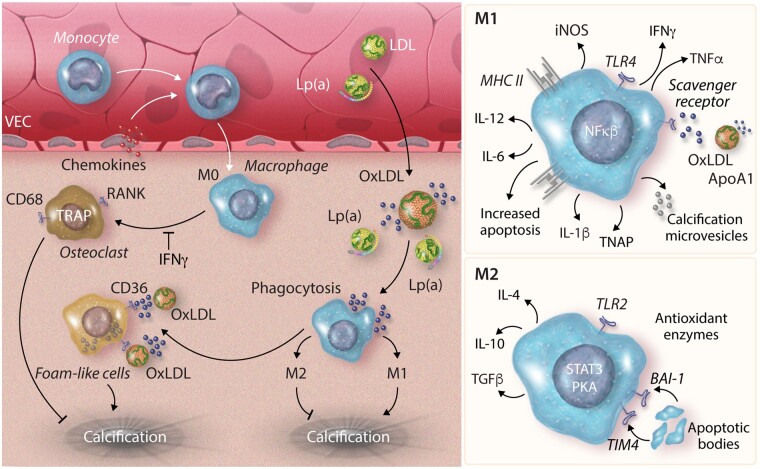

Figure 2.

Monocyte and macrophage differentiation within the valve. Monocyte infiltration into the valve occurs through chemotaxis gradients from chemokines produced by VECs. Monocytes differentiate to M0 macrophages within the valve. Macrophages phagocytose oxidized lipid particles (ApoA1/oxLDL) and become lipid-laden foam cells, which contribute to calcification. M0 macrophages may differentiate to osteoclast-like cells in the absence of IFNy, which aid in calcium reabsorption and the inhibition of valvular calcification development. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages increase expression of MHC class II receptors to present antigens to T/B cells. M1 cells also produce pro-inflammatory cytokines promoting apoptosis through the uptake of oxidized lipid particles and release microvesicles implicated in calcification promotion. Conversely M2 macrophages promote an ant inflammatory environment, phagocytosing apoptotic bodies and producing anti-inflammatory cytokines. BAI1, brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1; IFNγ, interferon gamma; iNOS, induced nitric oxide; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); MHC II, major histocompatibility complex II; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; PKA, protein kinase A; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B; STAT3, signal transducer and activator transcription 3; TGFβ, tumour growth factor-beta; TIM4, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 4; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNAP, tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; VECs, valvular endothelial cell.

5.2.2 Macrophages

Once resident within the tissue, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells, joining the tissue resident macrophages already present within healthy valves.74,75 Macrophages have long been associated with progression and severity of atherosclerosis, considered central drivers of vascular inflammation and central to early inflammatory cycles.76 With early-stage valve disease driven by immune cell infiltrates, histopathological evidence has been collected proving the presence of macrophages within aortic valvular lesions.77 Following endothelial dysfunction within the valvular leaflet, adhesion molecules are elevated within the VECs, allowing for increased immune cell infiltration contributing to active extracellular matrix remodelling and haemodynamic progression. Macrophages further differentiate into pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages; however, this simplistic bifurcated process has evolved in recent years.78 Pro-inflammatory macrophages produce induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TNFα, IL-6, IL-12, and produce MCP-1, all of which act to promote inflammation and the attraction of monocytes to the local area to further propagate the inflammatory response. Additionally, M1 macrophages promote calcification within VICs through their secretome, consisting of pro-calcific modulators, including TNFα and IL-6. In addition, the role of extracellular vesicles containing a variety of pro-inflammatory and pro-calcific cargo has recently become implicated in cardiovascular calcification.79 Extracellular vesicles secreted by activated macrophages are shown to nucleate hydroxyapatite crystals and serve as nucleation sites for microcalcification in the early stages of mineralization,80 further highlighting the emerging pleotropic role of vesicles in disease progression. M1 macrophages also produce oncostatin M, which in combination with IL-21 promotes a JAK3/STAT3-dependent osteogenic mechanism in smooth muscle cells,81 which has been confirmed in cultured VICs.82 In contrast, M2 macrophages produce anti-inflammatory cytokines TGFβ, IL-10, and CCL22 among others,83 contributing to regulatory T-cell (Treg) proliferation and immunomodulatory functions.84 Within aortic valve disease, overwhelming production of inflammatory cytokines promoted a significant shift in the M1/M2 paradigm, with little to no M2 macrophages observed in vivo, highlighting the importance of the M1/M2 balance in management of pathogenic valve disease development.85

High levels of oxidized lipoproteins stimulate both tissue-resident and migrated macrophages through scavenger receptors, which may result in differentiation of foam cells77,86; however, characterization of these cells has been difficult in vivo. oxLDL impacts cells in a variety of ways and can promote a plethora of biological consequences such as enhanced monocyte maturation, increased adhesive properties, and growth factor production, all of which act in concert to promote mineralization and disease progression. Moreover, oxLDL uptake in macrophages has been demonstrated to promote both inflammation through increased IL-1β and TNFα production,87–89 whilst inhibiting interferon gamma (IFNγ)-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines. The stark dichotomy of responses may explain why oxLDL-laden macrophages maintain a chronic inflammatory phenotype, unable to shift towards a reparative state within the valve, continuously promoting inflammation.90 Notably, macrophages within the valve have the potential to differentiate into osteoclasts, which aid in the removal of calcium deposition within the vasculature.91 Whilst pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α have been demonstrated to increase osteoclast activity through the NFkB pathway,92 IFNγ, produced by cytotoxic T cells, may inhibit this phenotypic switch in vitro, through reduction in tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) gene expression leading to dysfunctional osteoclast-like cells, which promote the calcification build-up within the valve.93 Thus, new targeted therapies could focus on limiting IFNγ within the valve, allowing for a reduction of M1 macrophage differentiation and a promotion of osteoclastogenic, resulting in cell-mediated reduction of calcification.

5.2.3 Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs), present in the subendothelial layer in healthy heart valve leaflets, have a relatively unknown purpose within the valves. DCs function to process and present antigens to CD4+ T cells through an MHC class II dependent manner, leading to activation of proatherogenic Th1 cells in atherosclerosis.94 Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), present CCL17 within atherosclerotic lesions, are suggested to restrain Treg cells, limiting their atherosclerotic response and fostering progression of atherosclerosis through sustained inflammation.95 It is therefore plausible that this innate-adaptive axis may also function with a valvular pathology, with DCs presenting lipid-associated antigens to T cells, priming pro-inflammatory phenotypes, and promoting a cycle of inflammation and development of mineralization. Suggested to play a regulatory function in aortic valve stenosis, DCs are colocalized with oxidized lipid on the aortic side of the valve, suggesting a possible role in lipid-derived valve disease.67 Within both cancer and atherosclerosis, DCs are demonstrated to upregulate scavenger receptor A,96 which binds and internalizes lipids, inhibiting their ability to effectively stimulate allogenic T cells or present antigens, through MHC class II restriction. Little research has been done to determine the unique roles of DC subtypes and to understand whether modulation of DC differentiation to a specific lineage could promote anti-calcification effects in valvular disease.

5.3 Adaptive immunity and immunomodulation in aortic valve disease

Adaptive immunity within the valve and its role in CAVD development is currently not well understood. Whilst the presence of both B and T cells within the diseased valve was first seen decades ago, characterization of these cells has been much harder to elucidate, and their precise mechanism of actions still eludes researchers today. With increasing interest in the collaborative role of resident valve cells and adaptive immune cells, valvular research must now begin to focus on this emerging field.

5.4 T cells

As the role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease is now widely accepted, a growing interest pertains to the role of T cells within the field of cardiovascular disease. While the majority of historic T-cell research has been conducted in the realm of cancer, recent studies have been focused on the multifaceted role of this diverse cell population in atherosclerosis and other inflammatory cardiovascular pathologies. T lymphocytes have been also shown to promote pathological remodelling in myocardial infarction in the coordination with macrophages.44 A combination of data from in vivo imaging, cell-lineage tracing, and genetically modified mouse studies has highlighted the role of T-cell as critical drivers and modifiers in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, yet less is understood with regard to the role in valve disease (Figure 3).

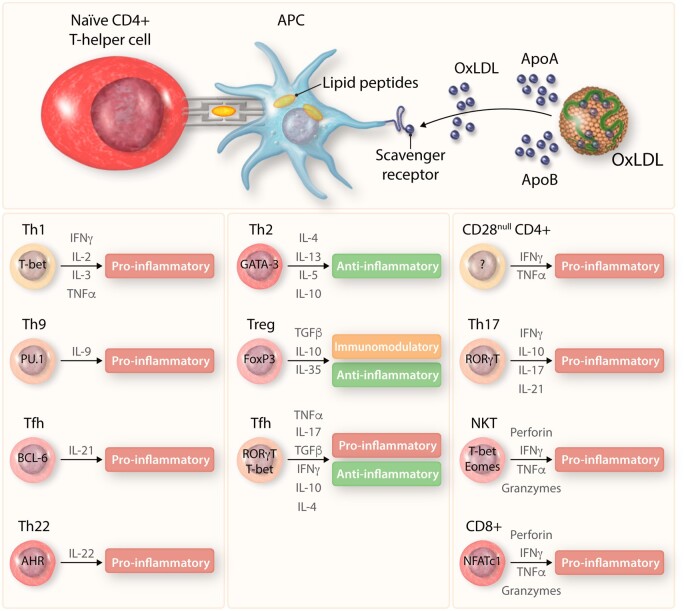

Figure 3.

T-cell differentiation within the valve. T cells primed through interaction with APCs differentiate into a range of cell types producing both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, aiding in the immunoregulation of aortic valve disease.

APC: antigen-presenting cell, IFNγ: interferon gamma, oxLDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein, TGFβ: tumour growth factor-beta, TNFα: tumour necrosis factor-alpha, ApoA/B: apolipoprotein A/B, T-bet: T-box transcription factor, PU.1: PU 1, BCL-6: B cell lymphoma 6, AHR: aryl hydrocarbon receptor, GATA3: GATA binding protein 3, FoxP3: forkhead box P3, RORγT: RAR-related orphan receptor gamma, Eomes: eomesodermin, NFATc1: nuclear factor of activated T cells 1.

T cells originate from a common lymphoid haematopoietic progenitor cells within the bone marrow, before moving to the thymus for maturation (hence the name). Following cycles of positive and negative selection, and recombination of the T-cell receptor (TCR), which allows T-cell specificity to be mounted against specific antigens, T cells exit the thymus predominantly as CD4+ or CD8+ naïve T cells, waiting to be primed. Important to note, however, the presence of a small subset of gamma delta (γδ) T cells. Defined via the expression of heterodimeric TCRs composed of γ and δ chains, opposed to α and β chains present within CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, γδ cells are activated in an MHC-independent manner, and more importantly have been shown to recognize lipid antigens presented by CD1 molecules, making them an interesting avenue for research into the lipid critical development of valvular calcification. Within the valve, 10–15% of the cells express the CD45+ lineage marker, which is crucial to activate phosphorylation and the subsequent downstream activation of TCR signalling.97 T cells are well characterized in the aged and diseased valve. Described histologically in the first instance as colocalizing with IL-2 receptors and being skewed towards a CD4+ rather than a CD8+ subset,98,99 T lymphocytes were not found in control tissue, instead found solely as a response to the degeneration and subsequent calcification of the aortic valve.77 More recently, cytotoxic T-cell infiltrates have been demonstrated to aggregate around the regions of calcification and arrayed round the newly formed vasculature, towards the expression of endothelial growth receptors and often accompanying osseous metaplasia. Towards end-stage non-rheumatic aortic valve stenosis, characterized by the high levels of valvular calcification, the coexistence of T lymphocytes and neoangiogenic within the valve is indicative of a chronic, immunomodulated process, giving weight to the concept of an adaptive immune cell response-mediated development of calcification. However, current studies have not succeeded in differentiating whether this infiltrate is predominately CD4+ or CD8+, or a combination of the two,74,100 and this remains up for debate. The relationship between atherosclerotic and valve disease T-cell infiltrates highlights the comparative difference between the two pathologies. The composition of the TCR repertoire differs between a stable atherosclerotic plaque, where the lymphocytes are suggested to be recruited via the lipid-stimulated macrophages101,102 and predominantly derived from a CD4+CD28null effector T subset.103,104 No shared clones within atherosclerosis and valve disease lymphocytes have been found, further promoting the hypothesis that valvular and vascular calcifications are district pathologies.

5.5 CD4+ T helper cells

Critical regulators of the adaptive immune response, CD4+ T cells have the capacity to differentiate into distinct T helper or T regulatory cells, which act to activate or dampen the immune response through interaction with other immune cells. The function of CD4+ T cells is multifaceted within the valve; however, specific modes of actions and mechanisms remain to be elucidated, underscoring the urgent need for more research into these complex cells.

5.5.1 Th1 cells

Characterized by the production of IFNγ, Th1 cells have been demonstrated to have deleterious roles in atherosclerotic plaques,105 but are significantly less characterized within the valve. Primarily involved in host defences, Th1 are crucial in response to autoimmunity, secreting IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-2, triggering both inflammatory and immunomodulatory cellular mechanisms within the local environment. Within the valve, IFNγ increases the antigen-presenting capacity of macrophages through induction of key chemokines and their receptors,93,106 promoting monocyte infiltration into the valve. IFNγ facilitates expression of adhesion molecules on VECs, fostering immune cell infiltration. Moreover, with IFNγ known to promote endothelial NOS production, LDL present within the aortic vessel becomes oxidized rapidly, contributing to lipid-driven valvular pathogenesis. TNFα secreted by Th1 cells has shown to enhance mineralization matrix nodule synthesis in osteogenic VICs.42 Promoting anti-fibrotic effects on VICs, TNFα has increased expression of RUNX2 and osteopontin, progressing osteogenesis of VICs within the valve.107 Of note however, TNFα is produced by a range of cells within the immune system, and that the role of TNFα in valves cannot directly be contributed to Th1 cells alone. Finally, IL-2 plays an important role in regulation of Treg cells, with inhibition of IL-2 signalling in Treg cells resulting in rapid DC activation and effector T-cell activation, promoting a pro-inflammatory environment within the tissue. IL-2, on the other hand, was not present within RHVD leaflets,108 but present in non-rheumatic tricuspid stenotic aortic valves,99 suggesting a stark difference in T-cell populations between the two valvular pathologies.

5.5.2 Th2 cells

Key cytokines IL-4 and IL-2 contribute to Th2 differentiation. IL-4 induces major transcription factor STAT6, upregulating GATA3 and promoting proliferation and enhances cytokine production. Notably, Th1 and Th2 cells inhibit one another’s differentiation. Associated with an immune response to extracellular pathogens; bacteria and viruses, Th2 cells promote a type II immune response, which interacts heavily with the innate immune system, stimulating eosinophil, mast cell and M2 macrophage recruitment.109 Classically related to allergic conditions, most notably asthma, production of IL-33 via Th2 cells within the valve has been identified in CAVD patients.110 In addition, IL-33 has been demonstrated to reduce the development of atherosclerosis through the receptor ST2 112. Soluble ST2 is a recognized biomarker in cardiovascular events, capable of predicting death among patients with heart failure and stratifying risk of sudden cardiac death, and could be a possible avenue for future serve as a marker of CAVD. Furthermore, IL-33 it is also suggested to reduce IFNγ production, thus reducing Th1 polarization further111 and can skew a predominantly Th1 cell population to a Th2 dominant population in vivo.112 IL-33 stimulation of VICs promotes differential phenotypic transition to osteoblasts via the p38/MAPK signalling pathways,110 highlighting the close relationship between the immune infiltrates occurring during early stages of CAVD and the subsequent development of valvular calcification.

5.5.3 Th17

Naïve CD4+ T cells mature to Th17 cells in the presence of IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, and critically TGFβ, with retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma T (RORyt) as the master regulator. TGFβ, which promotes Th17 maturation and proliferation, has also been implicated in Treg cell production, which acts in direct antagonization of Th17 cells, dampening down inflammation. Within CAVD, IL-6 and TGFβ are both present within the valves, enforcing the belief that naïve T cells could enter the valve before differentiating into Th17 cells and clonally expanding in response to the local milieu. IL-6 also exerts pleiotropic effects within the valve. In-depth sequencing has demonstrated the role of IL-6 in the role of VIC mineralization, stimulating the Akt and NFκB pathways.46 Concurrently, TGFβ has also been suggested to promote calcification of aortic valve leaflets, inducing aortic valve interstitial cell calcification through apoptotic mediated pathways.43 This may raise the question of whether the Th17 cells enter the valve as an ill-fated attempt to reduce development of calcification within this proapoptotic environment. Characteristically, Th17 cells release IL-17 in combination with IL-21 and IL-22, all of which have been implicated as key effector cytokines in the generation of autoimmune diseases. Notably, IL-17R is expressed on a multitude of tissues, and the effects of IL-17 often extend beyond a T-cell inflammation-driven response, driving expression of TNFα and a plethora of chemokines, attracting immune cells to the original source of damage. IL-17 has been implicated in both hypertension and atherosclerosis.113 The blockage of IL-17 suggested to decrease plaque size and induce differentiation of M2 macrophages that promote inflammation resolution and secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and participates in the induction of Th2 response.114 IL-17 is increased within CAVD patient plasma correlating with disease progression.115 Moreover, IL-21 can promote osteoblastic differentiation in VICs through the JAK/STAT3 pathway and upregulation of both alkaline phosphatase and RUNX2 expression in VICs,82 further evidencing the symbiotic relationship between Th17 cell presence in the valve and development of calcification.

5.5.4 Th9

Initially characterized as a Th2 subset, Th9 cells are classified as a distinct T-cell phenotype by their response to TGFβ and IL-4 and their subsequent secretion of IL-9, IL-10, IL-21, and notably do not produce IFNγ, IL-4, and IL-17. Involved in the defence against parasitic helminth infections and autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), in which valvular heart disease is the most common form of heart disease in this patient demographic,116 and could offer valuable insight into Th9 cells role in CAVD. Whilst there is no current literature concerning Th9 cells in valve disease, inference can be drawn from other cardiovascular pathologies. Increased expression of TGFβ has been associated with inflammation in RHVD , and may work in tandem with Th17 cells, collectively suppressing Treg and thus perpetuating inflammation.117 In atherosclerosis, it is unclear if Th9 cells are pro- or anti-atherogenic; however, IL-9 levels are increased in coronary artery disease plasma samples, and within atherosclerotic plaques.118 Conversely, however, no differences in Th9 prevalence within the peripheral blood was seen in both aortic dissection and acute coronary syndrome.119,120 Moreover, IL-9 secreted by Th9 cells has been demonstrated to partially induce vascular cell adhesion molecule -1 (VCAM-1) expression in aortic endothelial cells, mediating inflammatory cell infiltration in the atherosclerotic plaque,121 offering valuable insight into the complex relationship between the endothelium, leucocytes, and disease progression.

5.5.5 Th22

Th22 cells, considered similar to the Th17 subtype, produce predominantly IL-22. Initially associated with immunopathological skin diseases, they are now understood to act primarily on non-immune cells and are important in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as SLE and allergic diseases, thus indicating its role in acute inflammation. Unique to Th22 cells, they express IL-22 and not IL-17 and IFNγ; however, the cytokines responsible for inducing Th22 differentiation are unknown. Little is understood about the role of Th22 in cardiovascular disease; however, increased circulating levels of Th22 cells have been reported in patients with acute coronary syndrome.119,122 Moreover, IL-22 is higher in symptomatic atherosclerosis patients,123,124 with vascular repair suggested to be stimulated through IL-22-driven smooth muscle cell differentiation to a synthetic phenotype, contributing in part to the atherosclerotic plaque growth and smooth muscle migration into the intima. Conversely, within transgenic mouse models, microbiota-derived IL-22 has been shown to have anti-atherogenic effects125; however, this has not been validated in humans. Th22 cells may work in concert with Th17 cells to perpetuate inflammation, with Il-22 promoting elevation of IL-17 levels, working in a positive feedback loop to increase vascular dysfunction and disease development. However, little is known about their function in CAVD or RHVD.

5.5.6 Tfh Cells

Follicular T helper cells (Tfh cells) are resident within B-cell follicles, expressing both CXCR5 and CCR7, required for B- and T-cell homing, respectively.126 Within the follicle, Tfh cells promote IgA and IgG expression through CD40 ligand activation with B cells. Expressing high levels of IL-21, IL-6, and IL-4, circulating Tfh cells are suggested to promote inflammatory diseases such as SLE and rheumatoid arthritis127,128 and more recently have been shown to be pro-atherogenic in ApoE-/- mouse models, with their depletion reduces the atherosclerotic burden.129 Proliferation of Tfh cells can lead to increased production anti-oxLDL IgG1, a proatherogenic immunoglobulin known to induce atherosclerosis.130 In valves, little is understood regarding the role of Tfh cells; however, as oxLDL is known to be a classical mediator of valvular calcification, it could be suggested that increased Tfh cell populations may in part contribute to the pathogenic impact of oxLDL within the valve indirectly.

5.5.7 CD28null CD4+ T cells

CD28null CD4+ T cells are a recently characterized, pro-inflammatory subset of CD4+ Th1 cells. CD28, a costimulatory receptor critical for activation of T cells, is reduced in this Th1 subpopulation, and CD28null CD4+ T cells are almost undetectable within a healthy population. CD28 transduces costimulatory signals from CD80/86, and absence of this stimulation produces anergic T cells, producing significantly less IL-2, which is required for T-cell proliferation.131 High populations of CD28null CD4+ T cells are associated with chronic inflammation and correlate with poor prognosis, suggesting that these lymphocytes might play a key role in acute coronary syndrome, evidenced by a population observed within atherosclerotic legions.132 TNFα and IFNγ are both released by CD28null CD4+ cells, and uniquely this subtype has the ability to release cytotoxic perforin and granzymes that can damage tissue and further aggravate inflammatory responses both in vasculature and in valves.133,134 Furthermore, defects in the apoptotic pathways Bim, Bax, and Fas protect CD28null CD4+ T cells from induced apoptosis, suggested to provide a platform for clonal expansion within the valve, producing an inflammatory environment, enhancing cytotoxic effects to resident cells whilst promoting increased immune inflammation.135 CD28null CD4+ T cells express normal levels of immunosuppressive molecules such as CTLA-4 and PD-1. However, they exhibit increased expression of OX40 ligand, thus homing these cells to OX40-expressing endothelial cells, increasing immune cell infiltrate within the tissue,136 and could somehow explain the perpetuation of inflammation within the valve. Notably, within atherosclerosis, CD28null CD4+ T cells recognize HSP60, an autogenic driver of atherosclerosis, which further promotes CD28 loss in T cells while successively stimulating an immune environment through increased endothelial adhesion and NFκB activation.137 Notably, CD28null CD4+ T cells have not been identified in heart valve disease.

5.5.8 Natural killer T cells

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are categorized as innate lymphoid cells. Devoid of a targeted immune response, they release perforin and granzyme containing granules, as well as IFNγ, TNFα, and a host of immunoregulatory cytokines all of which serve to module the surrounding inflammatory response and regulate naïve T-cell differentiation.138 Expressing a semi-invariant TCR, NKT cells respond to glycolipids when presented via antigen-presenting cells. Suggested to be 5–15% of the peripheral blood, NKT cell prevalence is associated with valvular pressure gradients and disease severity,139,140 thus supporting the notion of non-specific immunity in valvular disease. However, with few studies concerning the presence of NKT cells in aortic stenosis or valve disease, little can be suggested regarding their role in CAVD.

5.5.9 γδ T cells

γδ T cells, unlike their αβ counterparts, do not recognize specific antigens, and whilst share many features with Th17 cells, including the polyfunctional expression of IL-17 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, there is little known about them within the development of both CAVD and RHVD. Suggested to be 2–5% of peripheral lymphocytes,118 γδ T cells are prevalent in atherosclerotic lesions in hyperchloremic mice. However, conflicting studies state their role within disease progression.141,142 In hypertension, γδ T cells are suggested to participate in low-grade inflammation associated with a rise in blood pressure and vascular injury;143 yet, more studies must be conducted to clarify the role γδ T cells play within cardiovascular and valvular diseases.

5.5.10 Treg

Treg cells exist as a natural thymus-derived subset with FOXP3 as the driving transcription factor, and conversely as peripheral induced Treg (iTreg) cells, which arise from the CD4+CD25- population following cytokine priming.144 Both subtypes of Treg cells serve to create a tolerogenic environment, limiting immune responses to antigens and promoting immunologic tolerance. Following clearance of pathogens, Tregs produce IL-10, TGFβ, and IL-35, suppressing pro-inflammatory responses and reducing IgE production. While increase in Treg populations has been found within severe aortic stenosis,145 little conclusions have been drawn about their precise role; however, insight can be drawn from their role in atherosclerosis.118,144,146,147 IgE, which is upregulated in atherosclerosis, activates mast cells and basophils, triggering acute inflammation and stimulating macrophage release of IFNγ and TNFα, which may be dampened down by Tregs.148–151 Considered an independent clinical predictor of coronary heart disease through accumulation of activated mast cells and neutrophil accumulation with the atherosclerotic lesion. IL-10, produced by Tregs, acts in part to produce a quiescent microenvironment, inhibiting monocyte and macrophage inflammation and cytokine production, reducing their ability to stick to the endothelial wall of the valve and infiltrate the leaflet. Furthermore, circulating IL-10 inversely correlates with calcium formation in the aortic valve.49 Within RHVD, the role of IL-10 is more apparent.37 IL-10 is significantly elevated in chronic RHVD patients, suggesting an ill-fated attempt by Treg cells to dampen down immunogenic responses. Mutations and presence of IL-10 are suggested to predict the severity of RHVD,50 further highlighting the divergent immune profile between non-rheumatic and rheumatic valve diseases.

5.6 Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells

Whilst CD4+ T cells have been further characterized as a subset within the valve, CD8+ cells remain more elusive. CD8 T cells, also known as cytotoxic T cells, play a crucial role in the protection against intracellular pathogens. Following recognition of a target cell, CD8+ T cells exert a three-pronged defensive mechanism. Firstly, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNFα, which instigates cellular apoptosis in target cells and IFNγ, promotes upregulation of MHC class I, cyclically inducing the inflammatory response. Secondly, the Fas ligand expressed on the CD8+ cell binds to the Fas receptor on the target cell, working in tandem with TNFα to further induce apoptosis in the target cell through activation of the caspase cascade. Finally, CD8+ cells release serine-protease granzymes and pore-forming perforin into the cleft between the membranes of the CD8+ cell and the target cell, resulting in breakdown of the membrane and targeting the cell for apoptosis.152 Production of IFNγ from this population has been suggested to drive the ectopic valve calcification.93 Moreover, the functional implication of the activated CD8+CD28- cells on osteoclastic function due to IFNγ has suggested to contribute to the progressive development of aortic stenosis.93,153 IFNγ has been demonstrated to impair osteoclast function, reducing its ability to resorb calcium, thus leading to calcium accumulation in CAVD.93 Within the valve, sequencing of the TCR in lymphocytes found within the valve in aortic stenosis patients suggests that the T-cell infiltrate is predominantly composed of a limited number of clonally expanded CD8+ T cells, and that this subset was also visible in the peripheral blood.154 The clonal T-cell expansion observed suggests firstly that the clonal expansion occurs within the valve tissue, rather than in the blood. Significantly, CD8+ T cells are not believed to be directly affected by trafficking of monocytes into the lesion, suggesting an independent role of T cells in the valve. More importantly, however, it is the suggestion that an adaptive immune response could be contributing to the mediation of valvular injury, rather than a brash innate attack of the valve due to damage. However, the magnitude of this contribution remains up for debate. Notably, within the CD8+ sub-populations, activated CD8+ T cells make up the majority of the CD8+ population, predominantly clonally expanded memory-effector CD8+ T cells.155 Within both atherosclerosis and valvular disease, most antigen specificity for these TCR clones has not been identified, posing an interesting avenue for future work. As ageing occurs, the prevalence of CD8+CD28- pre-senescent cells frequency increases within the peripheral blood,156 and during times of chronic viral infection, autoimmunity, and malignancy. The prevalence of these CD8+CD28- clones may contribute to the increased recognition of stress molecules, lowering the threshold for triggering clonal expansion and increased self-antigen recognition in CD8+ cells, explaining the increasing prevalence of cytotoxic T cells in CAVD.

5.7 B cells

B cells are distinct from most other immune cells due to their immunoglobulin-based B-cell receptors (BCRs), which recognize both self and foreign antigens. Developing from haematopoietic precursors within the bone marrow and maturing in the spleen, each B-cell clone develops a unique BCR through variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) [V(d)J] gene recombination. Through comparative atherosclerotic and aortic stenosis studies, B cells have been shown to be an important cell type within the formation of pro-atherogenic immune responses and development of atherosclerotic plaque, specifically through secretion of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and limited production in IL-17.157 B-cell subtypes, B1 and B2 cells, have been described in murine atherosclerosis models; however, they are still to be fully validated within the human vessel.158 B1 B cells are suggested to be anti-atherogenic through the secretion IgM, an oxidation-specific epitope-reactive antibody in a diet-induced atherosclerotic model.159 Conversely, depletion of B2 within the mouse leads to pro-atherogenic through the loss of total serum IgG, specifically IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2c and IgG1 and IgG2a within the plaque itself.160 Within CAVD, it is suggested that B cells may promote a Th1 proatherogenic phenotype in T cells through its response to oxLDL presented by activated macrophages and DCs. In severe aortic stenosis, the presence of B cells within the valves has been reported,140 with prevalence of B cells not correlated with confounding calcification. Importantly, the number of B cells has been shown to associate with the severity of stenosis,98 suggesting a negative impact on the progression of valve disease and highlighting the important role of B-cell-mediated immune response. It is speculated that B-cell accumulation and their subsequent interaction with macrophages may be implicated in the progressive thickening and calcification of the valves due to their colocalization and known bidirectional interaction,161 suggesting a progressive cycle of pro-inflammatory antigen presentation and production of pro-inflammatory markers linking B cells to valvular pathogenesis.

5.8 Pathogenic clonality within the immune system

Clonal haematopoiesis (CHIP) is a common condition in which a substantial fraction of an individual’s blood cells derives from a single dominant haemopoietic stem cell clone. Driven by random somatic mutations, these mutations provide numerous advantageous benefits to the mutated cells, which include mature blood and immune cells and has been demonstrated to increase in prevalence with age.162 Unexpectedly, CHIP has been strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality and increased of coronary artery disease and progression of mineralization, with carriers four times more likely to experience myocardial infarction than non-carriers.163,164 Unassociated to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, recent studies into these mutations provide new risk factors and direct and casual causality to disease progression.165 Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2) and DNA(cytosine-5) methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) are the most common age-dependent mutations, contributing to almost 70% of all acquired sequence variations.162 Mutations in both genes have been shown to regulate inflammatory potential in circulating leucocytes and are correlated with the incidence of degenerative calcific aortic valve stenosis and chronic inflammation.164 Moreover, patients with the variant allele frequency of >2% in both genes had a significantly lower cumulative survival than those with no mutations in the same cohort. Notably, the presence of CHIP in peripheral blood cells was associated with nearly a doubling in the risk of coronary heart disease and with accelerated atherosclerosis in mice,163 and when taken together suggests that somatic mutations in both atherosclerosis and CAVD may provide valuable insight into the role of haemopoietic cells in both pathologies. Mutations in either TET2 or DNMT3A are accompanied by increased inflammation due to the activation of the inflammasome complex, raising both IL-6 and IL-1β expressions, further highlighting CHIPs central role in inflammatory disease progression.166 Mutations associated with CHIP have effects on immune effector cells,167 namely macrophages and neutrophils, which could account for the significant increase risk in those with CHIP.168 With CHIP considered a possible evitability with ageing, greater understanding of the role in CHIP and CAVD must be urgently sought, as the population ages. Therapies targeting one or more of these mutations may be useful for ameliorating risk of uncontrollable expansion of inflammatory cells within the valve, thus limiting damage.

5.9 Inflammation as a therapeutic target

Despite the plethora of treatment options currently available to atherosclerosis, the majority of these have little to no impact on CAVD progression, suggesting that in spite of the shared risk factors of these two pathologies, they remain distinct biological entities and should be treated differently. Largely due to the lack of understanding of underlying molecular mechanisms, drug therapy for CAVD is not available. Current treatments are limited and often pertain to surgical intervention, which due to the patient demographic, the majority of which are often older with co-morbidities, is a risky option and to be avoided if possible. Aortic valve replacement, using either a mechanical or a bioprosthetic valve, poses numerous risks, including increased complications due to anticoagulation for mechanical valves and the relatively short lifespan of bioprosthetic valves, which require additional surgery, further increasing the mobility rates for this avenue of treatment. The other option is transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Recently, the PARTNER 3 trial (the safety and effectiveness of the SAPIEN 3 transcatheter heart valve in low-risk patients with aortic stenosis), which assessed the use of surgical vs. TAVR, reported a reduction in primary outcome: all-cause mortality, all stroke and re-hospitalization, of 46% in the 1-year follow-up after TAVR compared to surgical intervention,169 highlighting the need to move towards less invasive treatment strategies.

Current guidelines do not recommend pharmaceutical intervention to reduce CAVD progression; however, multiple clinical trials focusing on repurposing commonly used pharmaceutical interventions have been undertaken to slow CAVD progression and ultimately improve outcomes. Most recently, clinical trials such as the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) trial170 demonstrated that anti-inflammatory therapy targeting interleukin-1β within the innate immunity pathway led to significantly lower rates of recurrent cardiovascular events, highlighting both the untapped possibility of pharmaceutical intervention and the important role the immune system plays within cardiovascular disease. Conversely, the Study Investigating the Effect of Drugs Used to Treat Osteoporosis on the Progression of Calcific Aortic Stenosis (SALTIRE) trial utilized lipid lowering drug atorvastatin, attempting to halt or regress calcific aortic stenosis; however, researchers found no significantly beneficial outcome.171 Independently, the Calcium Acetate Renagel Evaluation-2 (CARE-2) study,172 a similar trial conducted in the USA using atorvastatin, found no decrease in coronary artery calcification progression. The results of these trials may suggest that statins do not act on the development of calcification via the same mechanisms in valves as they do in arteries or statins were introduced too late when calcification in valves progressed to the point of no return. Furthermore, Lp(a), a known risk factor of CAVD independent of LDL levels, cannot be managed by statins,8,173 and thus, this may be the driving force behind CAVD, rather than traditional atherosclerotic risk factors. A secondary SALTIRE trial is currently under analysis for the use of osteoporosis drugs denosumab or alendronic acid to reduce calcium release from bones into the bloodstream, and while the results of which have not been published, it further highlights the move away from lipid modifying medications to alternative treatment strategies. Of note, drug repurposing studies may offer an expedited avenue of pharmaceutical intervention.174 Selective exportin-1 inhibitor KPT-330 was recently shown to reduce development of CAVD in Klotho-/- mice and regress calcification in vitro; however, clinical trials have yet to commence to assess KTP-330 effect in humans.175 Taken together, these trials demonstrate the divergent mechanisms at play within CAVD and atherosclerosis, with promising atherosclerosis treatments having no significant effect on CAVD clinical outcomes or progression,176 underscoring the desperate need for new pharmaceutical options.

6. Conclusions

Historically a passive development process similar to bone development within the valves, aortic stenosis, and associated calcification is now gradually accepted as a highly inflammatory process, with various immune cells playing vital roles in its development and severity. CAVD is the second most frequent cardiovascular disease after coronary artery disease, with a prevalence of 2% in the over 65 population.8 With clinical association between atherosclerosis and aortic valve disease, it can be hypothesized that, like atherosclerotic development, valvular pathogenesis is associated with a complex combination of the innate and adaptive immune cells in a pro-inflammatory cycle away from homoeostasis. While management of CAVD has improved significantly in the last 60 years, surgical intervention is the only treatment for symptomatic patients, which is associated with significant morbidity/mortality rates and high cost, underscoring the desperate need for pharmacological intrervetions if CAVD is to become a treatable condition. With the recent understanding of the determinantal role of clonal expansion and calcification-specific epitope presentation, exciting new treatment strategies focusing on immune regulation must begin to be developed if valve disease is to be managed and reduced in the coming decades.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01HL136431, R01HL147095, and R01HL141917 to E.A.].

Contributor Information

Francesca Bartoli-Leonard, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Cardiovascular Sciences, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Jonas Zimmer, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Cardiovascular Sciences, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Elena Aikawa, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Cardiovascular Sciences, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Center for Excellence in Vascular Biology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Human Pathology, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia.

References

- 1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maganti K, Rigolin VH, Sarano ME, Bonow RO. Valvular heart disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:483–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark MA, Arnold SV, Duhay FG, Thompson AK, Keyes MJ, Svensson LG, Bonow RO, Stockwell BT, Cohen DJ. Five-year clinical and economic outcomes among patients with medically managed severe aortic stenosis: results from a Medicare claims analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]