Abstract

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) is a pathologic immune-mediated remodelling of the vasculature in transplanted hearts and, by impairing perfusion, is the major cause of late graft loss. Although best understood following cardiac transplantation, similar forms of allograft vasculopathy occur in other vascularized organ grafts and some features of CAV may be shared with other immune-mediated vasculopathies. Here, we describe the incidence and diagnosis, the nature of the vascular remodelling, immune and non-immune contributions to pathogenesis, current therapies, and future areas of research in CAV.

Keywords: heart transplantation, chronic rejection, innate and adaptive immunity, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells

This article is part of the Spotlight Issue on Cardiovascular Immunology.

1. Introduction

Transplantation of vascularized allografts is both a life-saving therapy and an ongoing clinical experiment in immunology in which the recipient’s immune system responds to a transplanted organ, including and especially the blood vessels of that organ, and pathologic changes induced in graft vessels may lead to graft failure. This is most evident in cardiac transplantation, perhaps because the coronary vasculature and cardiac perfusion are routinely and regularly assessed as part of cardiac care, but similar pathologies may occur in other vascularized allografts.1,2 In this review, we will focus on the remodelling of graft vessels, particularly of the arterial tree, that is responsible for most late cardiac graft loss, a process commonly known as cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV). Many of the insights gained from cardiac transplantation may be applicable both to other transplanted organs and to immune-mediated diseases of the native vasculature, such as antiphospholipid syndrome3 as well as in various immune-mediated vasculitides.4

2. Incidence/epidemiology

The short-term survival after heart transplantation has improved considerably in recent decades with 1-year post-transplant survival rates in the current era exceeding 85% worldwide.5 However, despite progress in immunosuppression, surgical techniques, and patient care, the survival beyond 1 year after transplantation has remained relatively unchanged with a median survival of 11.9 years in the 1982–91 era and 14.8 years in the 2002–9 era.5 CAV remains the leading long-term cause of death and re-transplantation following heart transplantation.5–7 Data from the most recent ISHLT registry indicate that CAV and late graft failure accounts for the majority of patient mortality at 5–10 years (32%), surpassing the contributions of malignancies (22%) and infections (11%).5 Male recipients are more likely to develop CAV than females, perhaps because of more co-morbidities,5 however, the there is no long-term survival advantage of being female.8

The incidence of CAV increases over time, developing in ∼30% of patients at 5 years and almost 50% at 10 years.5 Encouragingly, incidence of CAV may be changing in response to new diagnostic modalities to detect early disease and to new therapeutic interventions to prevent CAV progression. In comparing two eras, 1983–98 and 1999–2011, at a single centre, a higher rate of CAV development was reported in the early era (38%) vs. the more recent era (23%).9 Recent International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry data support this finding showing that survival in patients with CAV has improved in the most recent era, perhaps owing to the availability of therapies that may prevent disease progression.5 It will be important to see if this trend has continued when more recent cohort data are reported.

3. Risk factors

Risk factors for the development of CAV can be categorized as immune and non-immune. Non-immune risk factors related to the organ donor include old age,10 explosive brain death,11 and ischaemia–reperfusion injury.12 In the recipient, the risk of CAV shares many factors associated with native coronary artery disease, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolaemia. Although evidence confirming a direct link between post-transplant hypertension and CAV is limited, there are data suggesting that the use of antihypertensive therapy decreases CAV progression.13–15 More than 30% of adult heart transplant recipients are diabetic 1 year after surgery.5 Insulin resistance and a proinflammatory state are associated with the development of CAV.16,17 Both clinical and experimental observations suggest that hyperlipidaemia is an important contributor to CAV18–20 correlating with benefits from statin therapy.21 Earlier clinical studies have shown an association between evidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and the development of CAV.22–24 However, in the current era of antiviral prophylaxis, CMV infection appears to have a diminished impact on CAV,25,26 with the risk of CAV seen mainly among recipients with CMV breakthrough infection.27

CAV is generally considered to be primarily an immunologically mediated disease thus, immune risks associated the host’s allogeneic response likely outweigh non-immune risk factors. The two major immune risk factors associated with the development of CAV are the presence of alloantibody and occurrence of acute rejection. Experimental28–30 and clinical studies25,31,32 support the finding that pre-formed or de novo post-transplant donor-specific alloantibodies (DSA), especially those targeting HLA class II antigens25,33 are important risk factors for CAV. In addition, autoantibodies against self-antigens, such as vimentin, cardiac myosin have been shown to be independent risk factors for the development of CAV,34–36 even though cardiac myosin is not expressed in the vessel wall. Acute cellular rejection (ACR) occurring in the first 6–12 months year after transplantation is an independent risk factor for CAV progression with recurrent episodes having a cumulative effect of the onset of CAV.25,37 There is clearly a complex interplay between immunological and non-immunological risk factors ultimately leading to endothelial injury and the development of disease.

4. Clinical presentation

The denervated transplanted heart prevents recipients from experiencing ischaemic pain. Therefore, patients with CAV can be asymptomatic for some time or have non-specific symptoms of fatigue, nausea, or abdominal discomfort. Patients may eventually present with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure symptoms. Alternatively, due to the lack of premonitory signs, CAV can often present as sudden death, silent myocardial infarction, or severe arrhythmia.38,39 Another less common presentation is heart failure symptoms due to severe diastolic dysfunction (normal LVEF) which is due to microvasculopathy or small vessel CAV. PET and cardiac MRI studies demonstrating reduced myocardial flow reserve in heart transplant patients (consistent with this microvasculopathy) have been shown to have decreased survival.40

5. Biomarkers

The clinical benefit of a reliable biomarker to detect or better yet, predict CAV is that a positive result will lead to the early addition of a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTor) inhibitor, which slows the progression of CAV, while a negative result could reduce the frequency of coronary angiography.41 Brain natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein have been suggested as biomarkers for the development of CAV.42 Although both show a certain sensitivity and involvement in the development of CAV, they lack sufficient specificity.43,44 Certain micro RNAs (miRNAs) also have potential as clinically useful biomarkers since serum levels of microRNA (miRNA) have been shown to reflect immunologic activity within the allograft.45 Two endothelium-enriched miRNAs, miR-126-5p and miR-92a-3p, combined with age and creatinine conferred good discrimination between patients without and with CAV.46 In another study, a different miRNA, miR-628-5p are was found to be significantly elevated in heart transplant recipients with CAV with a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 83% to predict CAV.47 However, a prospective study is needed to determine if miRNA will be able to detect incipient CAV.

Since inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of CAV, immune mediators could serve as potential biomarkers. An early study suggested that the development of CAV after heart transplantation was predicted by early elevation of plasma soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels, even at early time points.48 More recently, combining the concentrations of interleukins-4, -6, -10, -21, -23, -31, and -33, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and soluble CD40 ligand led to the development of a cytokine score with high sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between patients with and without advanced CAV, thus being a candidate for a novel, non-invasive test.49 Finally, a multicentre study of 200 patients examined various candidate biomarkers including serum antibodies, angiogenic proteins, blood gene expression profiles, and T-cell alloreactivity to identify clinical, epidemiologic, and biologic markers associated with adverse clinical events past 1-year post-transplantation. Only anti-CM antibody and plasma levels of VEGF-A and VEGF-C were associated with an increased risk of adverse events.50

Donor-reactive CD4 T-cell immunity specific for donor-derived peptides (indirect pathway) likely participates in the development of CAV.51–53 It has been postulated that CD4 T cells responding donor peptide continuously shed by an allograft play a dominant role (over direct reactivity) in the development of chronic immune-mediated injury.54 To determine if assessment of the indirect pathway could serve as a biomarker for CAV, anti-donor cellular immunity was determined in 65 primary heart allograft recipients by IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays using donor HLA-derived peptides. Immune reactivity in cardiac transplant recipients with CAV differed significantly from those without CAV but the detected responses were heterogeneous in nature suggesting that a single surrogate marker is insufficient to optimally detect CAV in heart transplant recipients. The search for biomarkers of CAV continues.

6. Vascular changes in CAV

The coronary vasculature supplies blood to the myocardium and consists of arteries, capillaries, and veins. Recipients of heart allografts may develop pathological changes within the donor blood vessels that lead to a spectrum of disease ranging from no cardiac dysfunction to myocardial ischaemia, infarction, heart failure, and death. Various terms have been used to describe this entity reflecting the different focus of pathologists and clinicians studying the disease, the modalities used to diagnose abnormalities, and the time at which studies are performed during disease evolution. CAV (with the emphasis on vasculopathy) is a broad descriptor of pathological processes affecting the blood vessels of transplanted hearts.55 Although changes are found in coronary veins, the clinically relevant features are arterial lesions also referred to as graft arteriosclerosis.56 Initial descriptions of CAV were in an era of suboptimal immunosuppression, in which survival was relatively short and often associated with severe acute rejection within months of transplantation.57 With modern immunosuppressive therapy, CAV usually progresses over years and is associated with no or mild acute cellular rejection.58 Serial imaging studies have improved the understanding of early lesion development and disease progression beyond the characterization of advanced CAV in autopsy specimens.

CAV is typically described as diffuse and concentric narrowing of large epicardial and small intramyocardial arteries. The characteristic findings are intimal fibromuscular hyperplasia, atherosclerosis, and vasculitis.58,59 There are numerous similarities and differences of CAV with focal atherosclerotic lesions of proximal coronary arteries in native hearts. Intimal thickening and fibrofatty plaques are common to both, though fatty streaks, intimal erosions, fibrous cap thinning, haematomas, thrombosis, marked disruption of elastic laminae, and calcium deposition are less common in CAV.60 Pre-existing atherosclerotic disease in transplanted hearts can contribute to disease burden, but the presence of atheromas in transplanted paediatric hearts also suggests accelerated atherosclerosis in CAV.59 Despite a diffuse process, there is variability between affected arteries and intramyocardial artery involvement is not always present. Intravascular ultrasound early after transplantation confirms heterogeneity of CAV and suggests focal origins and eccentric development of lesions that later coalesce to produce the characteristic continuous, concentric lesions. Serial intravascular ultrasound has defined changes in vessel circumference in addition to the intimal thickening and lumen loss noted in histological analysis and coronary angiography. Similar to studies of atherosclerotic coronary arteries, vascular remodelling is an important determinant of lumen loss in CAV.61,62 Outward vascular remodelling (artery enlargement) may compensate for intimal thickening, while inward vascular remodelling (artery shrinkage) exacerbates luminal stenosis. CAV is characterized by a failure of compensatory outward remodelling and pathological inward remodelling of proximal segments is associated with adverse events.63 The mechanisms for vascular remodelling are poorly understood and may reflect endothelial-mediated responses to altered blood flow or direct cytokine effects on smooth muscle cells (SMC).64 Additionally, adventitial fibrosis is thought to drive inward vascular remodelling. Therapy to prevent CAV may differentially regulate these processes and rapamycin decreases intimal thickening but preserves vessel diameter and increases lumen size.65

Vasomotor responses that regulate myocardial perfusion are diminished in CAV. Infusion of endothelial-dependent vasodilators, such as acetylcholine, fail to dilate or paradoxically constrict epicardial arteries after cardiac transplantation, particularly in diseased segments.66 In contrast, direct vasodilators, such as agents that generate NO, had appropriate effects suggesting a sensitivity of endothelial cells to immunological injury and a relative sparing of SMC. Early endothelial dysfunction of epicardial arteries predicts the subsequent development of CAV suggesting a causal link.67 Furthermore, baseline epicardial and post-transplant microvascular dysfunction, measured by flow parameters, are predictors of worse outcomes implying a critical role for SMC function in conduit and resistance arteries.68

Intimal thickening is the pathological hallmark of CAV and largely results from an accumulation of SMC and the matrix they produce.69 An infiltrate of T lymphocytes and macrophages contributes to the intimal expansion.70 A majority of the T cells are memory cells that express interferon-γ and transforming growth factor-β.71 SMC are more numerous in the deeper part of the intima near the media, whereas leucocytes localize closer to the luminal endothelium (endothelialitis). Diffuse infiltrates and aggregates of B and T lymphocytes and macrophages are commonly found in the adventitia, organized as tertiary lymphoid organs that form at sites of chronic inflammation.72 The media is typically spared of infiltrates, has a normal appearance, and may explain intact SMC vasoresponses in many epicardial artery segments. Occasionally, severe transmural infiltrates occur or a profound loss of SMC with medial fibrosis is seen.59 Loss of relative medial immune privilege likely requires a more robust immune response.73 Although resident leucocytes may be transferred to the host within the allograft (passenger leucocytes) and initiate immune responses, the leucocytic infiltrates of rejecting grafts are of host origin. The origin of intrinsic vascular cells is more controversial because of inappropriate experimental models. In human cardiac allografts, the proliferating SMC within the intima remain of donor origin.74 A minority of luminal endothelial cells in CAV are of host origin and could reflect repair/repopulation of endothelial injury sites resulting from transplantation or alloresponses.75 However, most replacement by host endothelium is confined to the cardiac microvasculature and does not vary with the number of rejection episodes.75

Phenotypic modulation of SMC from a primarily contractile cell in the media to synthetic, proliferating, and migratory states in intimal lesions occur in atherosclerotic plaques and may contribute to CAV lesions.76 If the identification of SMC relies on the expression of contractile markers as is typical in analyses of CAV, the number of cells of SMC origin may be underestimated. Application of lineage-tracing and transcriptomic studies in murine models has shown larger than expected contributions of SMC to atherosclerotic plaques. SMC differentiate into other cell types, including macrophage-like, myofibroblast-like, osteochondrogenic-like, and mesenchymal stem cell-like cells.77,78 The phenomenon of SMC differentiation to macrophage-like cells has been demonstrated in human atherosclerotic plaques and in coronary artery lesions of a single transplanted heart by detection of histone modifications restricted to the SMC lineage and donor/recipient-specific sex chromosome markers.77,79 In addition to intimal SMC arising from pre-existing intimal and medial SMC, they may arise from endothelial to mesenchymal transition as occurs in embryonic development of the heart or from progenitor cells residing in an adventitial niche.80,81 Endothelial to mesenchymal transition has been shown in clinical specimens and experimental models of human CAV since a significant portion (∼10%) of intimal cells co-express endothelial and SMC markers.82 Further application of novel diagnostic modalities to clinical specimens may elucidate further unexpected transdifferentiation among SMC, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages in CAV.

7. Pathogenic mechanisms

The arterial system may respond to injuries by remodelling, potentially altering wall thickness, luminal diameter, and vessel circumference. Consideration of whether pre- or peri-transplant injuries contribute to CAV involves understanding the types of injury to which the allograft vasculature is potentially subjected and whether such injuries result in remodelling responses resembling CAV-like lesions. Biomechanical alterations in blood flow or pressure may affect vessel lumen and circumference, but effects on wall thickness involve the media, not the intima or adventitia that are principally altered in CAV.83 Early studies in animal models of arteriosclerosis that involved denudation of the arterial endothelium through mechanical injury did lead to intimal hyperplasia, but subsequent work in which endothelial denudation was induced without concomitant injury of smooth muscle resulted in a lesser response restricted to sites at which the endothelial lining failed to regenerate.84 The endothelial lining remains intact overlying CAV lesions and allograft arteries are unlikely to suffer SMC mechanical injury, suggesting that injury must take other forms. SMC injury in allografts may result from sterile in inflammation, such as that produced cold or warm ischaemia and exacerbated by reperfusion.85 Sterile injury alone appears insufficient to induce CAV-like arterial changes following syngeneic heterotopic heart transplantation86 or in allogeneic heterotopic heart transplantation into mouse SCID or Rag2−/− hosts lacking adaptive immune responses.87 Nevertheless, sterile inflammation caused by ischaemia reperfusion is a recognized risk for developing CAV.60

The lesions in the arterial wall caused by atherosclerosis differ from those of CAV regarding cellular and extracellular composition as well as the restricted location, eccentricity, and focality of atheromas.60,88 Nevertheless, both lesions involve intimal and adventitial changes that result in luminal narrowing compensated by inadequate outward remodelling. Furthermore, many patients will require cardiac transplantation due to ischaemia associated with atherosclerotic vascular disease, and hyperlipidaemia likely to be present in these patients is a risk for CAV.89 Furthermore, while hearts with severe coronary artery disease are un likely to be used for transplant, most donor organs will have some degree of prior atherosclerotic involvement. Consequently, atheromatous lesions may be found in the coronary arteries of patients with CAV. However, such pre-existing atheromas tend to be covered over by more characteristic CAV-like changes, thus appearing to be superimposed upon pre-existing atheromas. This finding can be replicated in human immune system mice receiving a graft coronary artery segment with pre-existing atheromas.90

A large number of studies, primarily from a single centre, have found a significantly increased risk of CAV in the setting of CMV infection and CMV antigens have been detected in some CAV specimens.91 Natural CMV (as opposed to laboratory strains) readily infects endothelial cells and may cause injury or impair anti-inflammatory functions.92 CMV infection in rat heterotopic cardiac allografts enhances vasculopathy.93 These lesions are associated with inflammation. To date, there is no model in which CMV directly causes CAV-like lesions through intrinsic effects on vascular cells.

As noted earlier, the primary driver of CAV is thought to be the immune system of the host and alloantigens are important because CAV lesions stop at the suture line between donor and recipient. However, most of the evidence re specific pathogenic mechanisms is indirect: recipient T cells, B cells, and macrophages are found in or around affected vessels and donor-specific antibodies, especially those reactive with donor HLA-DR and DQ are frequently present and bind to class II HLA molecules expressed on human graft endothelial cells. Animal models, which are often used to test disease mechanisms have been of limited use in CAV: they typically involve much lesser degrees of immunosuppression than occurs in clinical settings; rodent recipients typically do not make an anti-graft antibody response and rodent endothelial cells typically lack class II MHC molecules; and most importantly, the endothelial and smooth muscle cells that form the arteries with expanded intimas in artery graft and heterotopic heart models are largely of host origin following loss of donor cell populations within the first few weeks post-transplant86 unlike in clinical specimens in which the cells in CAV lesions remain overwhelmingly of donor origin.74,75 Human coronary artery grafts into human immune system mouse models do produce CAV lesions comprised of donor vessel cells, but these models also rarely utilize clinical levels of immunosuppression and may more represent subacute rejection than chronic rejection.

Most early concepts of CAV pathogenesis focused on cell-mediated immune responses.94 Graft alloantigens, especially HLA Class I and Class II molecules, are expressed principally on graft endothelial cells and are targets for the activation of host T and B cells. Many of these T cells may be bystanders rather than graft specific.95 T-cell populations in the vessel wall of clinical CAV specimens are enriched for lymphocytes that producers IFN-γ and TGF-β.96 While IFN-γ is most characteristically made by CD4+ Th1 cells, CD8+ CTL, and NK cells, TGF-β is more associated with CD4+ T regs, which by other markers do not appear to be present in the vessel wall.96 In a mouse heart transplant model, genetic ablation or antibody neutralization of IFN-γ prevented vasculopathy though interestingly not acute graft rejection.97 When human arterial segments are placed as aortic interposition grafts in immunodeficient mice, human IFN-γ will induce intimal expansion by smooth muscle cells.64,98,99 If the same animals are given T cells allogeneic to the artery graft, neutralizing IFN-γ prevents intimal expansion,99 while neutralizing TGF-β abrogates medial sparing without reducing intimal expansion.100 These studies led to the hypothesis that IFN-γ is the primary driver of CAV.101 In mouse models, CD4 T cells and NK cells appear to interact in the production of IFN-γ.102

More recent work has focused on the role of anti-graft antibodies in CAV. Patients with CAV frequently have developed DSA to highly polymorphic donor HLA-DR or DQ or, when allogeneic differences exist, to less polymorphic MICA proteins.103 In models involving human artery grafts in immunodeficient mice, repeated administration of a complement-fixing mouse anti-human HLA-A, B, C monoclonal antibody that binds to endothelial cells of the implanted artery induces intimal expansion in the absence of human lymphocytes.104 Although this antibody can directly induce a number of signalling events in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, the production of CAV-like changes in vivo appears to be dependent upon mouse host NK cells, likely through production of IFN-γ.104 Autoantibodies to angiotensin II type 1 or endothelin type A receptors also occur and appear to be antibody-mediated rejection, but the effects may be more profound on the microvasculature than the arterial tree.105

Although cellular and humoral immunity are often viewed as alternative responses, they may actually work together. A single dose of human alloantibody in immunodeficient mice bearing human coronary artery grafts will activate complement deposition of polyC9 on the endothelium, but is insufficient to cause intimal expansion when the artery is transplanted into a second mouse host. However, transplanting replicate artery segments into a second host that has circulating human T cells from a donor allogeneic to the artery increases T-cell recruitment, activation, and IFN-γ production leading to dramatically increased CAV-like changes in the artery graft.106 The enhanced T-cell response caused by DSA but not the basal T-cell response is dependent upon complement. PolyC9 is internalized by endothelial cells where it activates a variety of signalling pathways including production of IL-1, which in turn, activates the endothelial cell to express adhesion molecules and chemokines that mediate T-cell recruitment.107 Complement-activated endothelial cells also express IL-15 and IL-18 which drive T-cell activation.108,109 B cells in arteries showing CAV are most often found in the adventitia in structures resembling tertiary lymphoid organs. Such cells were posited to be a source of DSA, receiving help from alloreactive T follicular helper cells, but recent cloning and expression of the immunoglobulins made by these B cells suggests they may instead by polyreactive antibody producers.110

Innate immune cells may also play a role in CAV pathogenesis, but it is unclear if these cells are independently sensing allogeneic differences or whether they are being directed by T cells and/or antibodies. Macrophages are potential sources of growth factors that could contribute to intimal SMC expansion, and depletion of macrophages reduces the extent of CAV-like lesions in mouse heterotopic heart models.111 In contrast, macrophages appear dispensable for formation of CAV-like lesions in human immune system mouse models. Further, since less is known about the phenotype of the macrophages present within the intima, it is also possible that they serve to restrain T-cell functions.

Just as cellular and humoral immunity may work in concert, immune and non-immune factors may also interact. Clinically, perioperative graft injuries, such as those produced by ischaemia/reperfusion, shortens graft survival and likely accelerates the development of CAV. In human immune system mouse models, modelling of ischaemia/reperfusion enhances the allogeneic T-cell response to graft vessels, leading to more T-cell infiltration and more IFN-γ production and more intimal expansion. Notably, such CAV-like lesions do not develop in the absence of adoptively transferred T cells. The augmented T-cell response requires complement activation as the enhanced, but not the basal T-cell response, is blocked by an anti-mouse C5 antibody. Complement activation in this setting depends upon ‘natural’ IgM antibodies that recognize alterations in the endothelium and in medial smooth muscle cells, activate complement on both cell types. This differs from the effects of DSA which selectively binds to endothelium, but the net effect is the same. These data suggest that increased CAV results from an augmented allogeneic response rather than accumulation of injury. Injurious agents other than those induced by ischaemia/reperfusion may also influence the adaptive immune response. For example, hyperlipidaemia has been shown to augment T-cell responses independent of its atherogenic effects on the vessel wall.89 CMV infection of graft endothelium may also augment and localize T-cell responses. Similarly, because endothelial cells are primary natural targets of CMV infection and because infected endothelium releases highly immunogenic exosomes that can stimulate recipient T cells, CMV infection of a graft boost IFN-γ production.112 NK cells may also contribute by releasing IFN-γ as part of the anti-CMV response.113

8. Therapeutic interventions to prevent or treat CAV

Therapeutic interventions targeting both immune and non-immune pathogenic mechanisms involved in CAV have been investigated with variable success. Current clinical treatment for CAV is primarily focused on preventative strategies including CMV infection prevention, rejection avoidance, vascular risk factor management, and specific pharmacotherapies, such as statins and mTOR inhibitors that reduce development of disease. Percutaneous revascularization for focal obstructive coronary stenosis and retransplantation for allograft dysfunction are also increasingly being utilized. These multi-faceted interventions have improved outcomes for patients with CAV over time.9

Mycophenolic acid (MPA) and mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) reduce the development and progression of CAV. MPA inhibits inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase required for lymphocyte de novo purine synthesis. A randomized controlled trial comparing MPA and azathioprine showed less coronary intimal thickening on intravascular ultrasound with MPA.114 The mTOR inhibitors prevent lymphocyte activation by inhibiting serine/threonine kinase mTOR, blocking interleukin-2 mediated signalling, and cell cycle progression from the G1 to S phase. Additionally, mTOR inhibitors inhibit fibroblast and smooth muscle cell proliferation that are responsible for coronary intimal hyperplasia in CAV. Table 1 summarizes the four randomized controlled studies of post-HT de novo mTOR inhibitor therapy with a strategy of calcineurin inhibitor dose-reduction or complete withdrawal.65,115–117 These studies have reliably shown reduced CAV incidence and disease progression as assessed by intracoronary vascular imaging. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 14 de novo and late conversion mTORi studies showed a 61% relative risk reduction in CAV for mTOR inhibitor treatment.118 The timing of therapy impacts efficacy with most studies demonstrating greater CAV attenuation when mTOR inhibitors are initiated earlier, generally within 2 years of HT.119,120 The variable effects according to time from HT is postulated to be related to predominant fibrotic plaque in early CAV compared to necrotic core and calcium plaques in later stage disease.121 Relevant risks associated with early post-operative mTOR inhibitor initiation include rejection with calcineurin withdrawal strategies, exacerbation of CNI nephrotoxicity, poor wound healing, infections, effusions, and cytopenias. The EVERHEART multicentre open-label trial randomizing patients to everolimus administered immediately or delayed until 4–6 weeks post-HT, reported greater adverse events for the immediate everolimus treatment group, largely due to higher rates of pericardial effusion (34% for immediate versus 20% for delayed).122 There was, however, no difference in the primary composite endpoint of wound healing and efficacy (defined as haemodynamically significant rejection, graft loss, or death). It remains uncertain whether an mTORi based maintenance immunosuppression regimen should be adopted for all patients to prevent CAV or only selected patients at high risk for developing CAV.

Table 1.

Randomized control trials of de novo mammalian of target rapamycin inhibitor and cardiac allograft vasculopathy in heart transplantation

| Study | Treatment arms | Follow-up | CAV endpoint | Non-CAV outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arora et al.115 |

|

3 years | ||

| Kobashigawa et al.116 |

|

1 year |

|

|

| Vigano et al.117 |

|

2 years | ||

| Keogh et al.65 |

|

2 years |

|

CAV, cardiac allograft vasculopathy; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

P < 0.05

Statins have lipid-lowering (mentioned earlier) and immunomodulatory effects that are beneficial for preventing CAV.123,124 In randomized controlled trials, statin therapy reduced the incidence of CAV and haemodynamically significant rejection and improved survival.125–128 Therefore, statins are recommended for all HT recipients and usually initiated early in the immediate post-operative period.

Focal epicardial CAV disease may be amenable to percutaneous coronary intervention. However, repeat revascularization rates are high due to restenosis and disease progression.129–131 One study of everolimus-eluting stents reported 1-year revascularization rates of 17% for target vessels and 26% for non-target vessels.132 Observational studies show lower in-stent restenosis for drug-eluting compared to bare metal stents but similar CAV related clinical events including death and myocardial infarction.133 Coronary artery bypass surgery is infrequently an option due to the typical diffuse nature of CAV disease and absence of poor distal vessel targets as well as increased operative risk related to patient comorbidities.134

Re-transplantation is the therapeutic option of last resort. Donor organ shortages and inferior outcomes compared to de novo HT limits re-transplantation as a treatment option for most patients with CAV. Re-transplantation is generally considered for selected patients with CAV who have severe disease (ISHLT grade CAV3) and associated allograft dysfunction.135 This practice was supported by international registry analysis showing similar outcomes from re-transplantation and medical management, but a survival advantage with re-transplantation for patients with CAV-associated systolic graft dysfunction defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of <45%.136

9. Key targets for CAV research

9.1 Prediction

Newer diagnostic methodologies have allowed detection of CAV at earlier stages, and clinical trials have shown benefit of pharmacotherapeutic prophylaxis for CAV progression. These diagnostic methodologies include the use of precision medicine, optical coherence tomography, coronary computed tomography angiography with fractional flow reserve, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Establishing a robust predictive model for CAV development based on biomarkers and clinical parameters could potentially replace the need for invasive imaging for CAV diagnosis. A recent international study of 1301 heart transplant recipients with protocol-based repeated assessment of CAV over 10 years identified 4 distinct trajectories of long-term CAV progression.25 Trajectory 1 was characterized by the absence of CAV over time (56% of patients), Trajectory 2 was composed of patients with no CAV at 1 year but with a late-onset of CAV starting around 4 years (8%), Trajectory 3 comprised patients with intermediate CAV grade at 1 year who experienced a moderate increase during follow-up (23%), and Trajectory 4 exhibited a pattern of intermediate CAV at 1 year with rapid evolution of disease over time (13%). CAV trajectories 3 and 4 were associated with higher mortality rates (10-year patient survival of 73.43% and 51.89%, respectively), in comparison with trajectories 1 and 2 that were characterized by 10-year patient survival of 80.01% and 83.49%, respectively.25 Multivariate analysis revealed six independent predictors contributing to the development/progression of CAV which include donor age, male gender of the donor, donor tobacco consumption, and first-year LDL-cholesterol >1 g/L, class II donor-specific antibody, and acute cellular rejection ≥2R.

First-year measurements of the transplant coronary artery wall using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can detect early CAV and provide intermediate-term prognosis. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a technique that uses an optical analogue of ultrasound to provide cross-sectional images with a super high resolution, 10-fold higher compared with IVUS and has been shown to be the most useful for this purpose.137 One of the properties of OCT is the ability to clearly differentiate among the wide variety of vascular wall components. It accurately represents the intima–media interface, classifying tissues as fibrous, homogeneous, fibrocalcified, poor in signal with well-defined borders, or diffuse borders, or with an abundant amount of lipids. In a sense, OCT provides virtual histology analysis of the vessel microstructure and remodelling. Although studies utilizing OCT contributed to a better understanding of the mechanism of CAV, current knowledge remains insufficient, and further studies are warranted to document its clinical relevance.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) is a non-invasive means to evaluate the vessel wall and the lumen. As an anatomical diagnostic tool, it provides high-quality and high-resolution images of the coronary arteries. However, the elevated resting heart rate of the denervated allograft, is a limitation. The performance of CTA with measurement of the fractional flow reserve derived from CT (CTFFR), allows measurements of the haemodynamic effect of any affected artery, on the coronary tree. A meta-analysis of 13 studies (n = 615 patients) with the evaluation of 9481 segments showed that CTA and conventional angiography were able to detect CAV (defined as any luminal irregularity) and significant CAV (stenosis ≥50%) with mean sensitivities of 97% and 94%, specificities of 81% and 92%.138 Quantitative CTA, in particular, the combination of lumen/wall measurements and proportion of fibrotic tissue, may aid the detection of early CAV, guide medical treatment, and ultimately improve patients’ outcomes. However, larger serial outcomes studies are needed to confirm its prognostic value. CT imaging can also be combined with positron emission tomography (PET) scanning to provide additional dynamic information, such as blood flow.

Being a minimally invasive diagnostic method, Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is being increasingly promoted because it allows the high-resolution visualization of the epicardial coronary arteries, and the microvasculature in the development of CAV. It is an attractive diagnostic modality since it does not require exposure to ionizing radiation and offers a multiparametric evaluation, which includes the evaluation of the ejection fraction and myocardial deformation, perfusion, and tissue characterization. In a study by Miller et al.,139 an evaluation of performance of CMR was made for detecting CAV using contemporary invasive epicardial artery and microvascular assessment techniques as reference standards. The CMR myocardial perfusion reserve significantly outperformed angiography for detecting moderate CAV (CI) [(0.79–1.00) vs. 0.59 (95% CI: 0.42–0.77), P = 0.01] and severe CAV [area under the curve, 0.88 (95% CI: 0.78–0.98) vs. 0.67 (95% CI: 0.52–0.82), P = 0.05]. Like observations in traditional atherosclerosis, stenotic microvasculopathy in the presence of no or mild CAV portended worse prognosis compared with the absence of stenotic microvasculopathy in the setting of no or mild CAV.140 Beyond the assessment of epicardial CAV, the detection of small vessel CAV with CMR appears to be promising and may predict outcome for this microvasculopathy form of CAV. However, it should be noted that there are limitations of using MRI imaging agents in some patients, e.g. with chronic kidney disease and repeat imaging may be complicated by heavy metal dye retention in the tissue.

Chih et al.141 have reported on the correlation of PET blood flow parameters to invasive haemodynamic measurement. PET MFR, stress MBF, and coronary vascular resistance (CVR) in 40 patients at a median of 3.2 years after transplant demonstrated poor diagnostic performance for detecting angiographic CAV 1–3 but high-diagnostic accuracy for detecting CAV on IVUS. Furthermore, PET significantly correlated with all invasive coronary flow indices. Konerman et al.40 studied the prognostic implications of rubidium-82 PET. In their study of 117 patients who were a median of 6.4 years post-HT the primary outcome included the composite of cardiovascular death, acute coronary syndrome, coronary revascularization, and heart failure hospitalization. At a median of 1.4 years of follow-up, an MFR <2.0 was associated with increased risk of the primary composite outcome (hazard ratio of 4.76). Finally, McArdle et al. studied 140 post-HT patients who underwent rubidium PET imaging at a median of 8.2 years post-transplant. He found that patients with an MFR ≤1.75 had a HR of 4.41 for adverse events at a median of 18.2 months of follow-up.142

Clinical studies have identified risk factors for CAV development and progression that corroborate the immunological basis of CAV (Figure 1). For example, a higher number of HLA antigen mismatches has been associated with severity of CAV.144,145 Contrary to this, HLA-DR matching is a strong and independent predictor of better post-transplant survival.146 Lastly, prior episodes of rejection, and particularly antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), have been correlated with CAV incidence.147 Another study demonstrated that complement pathway activation with C3d deposition seen on endomyocardial biopsy samples predicts CAV onset.148 Furthermore, the detection of donor-specific antibodies (DSA) post-transplant and, in particular DSA to class II antigens, is also associated with CAV and poor outcomes.33 Therefore, several studies have targeted the modulation of the immune system response as a strategy to alter CAV onset and progression. Given the strong association with complement-fixing DSA, targeting B cells, plasmablasts, and plasma cells or targeting the complement system are approaches under current investigation.

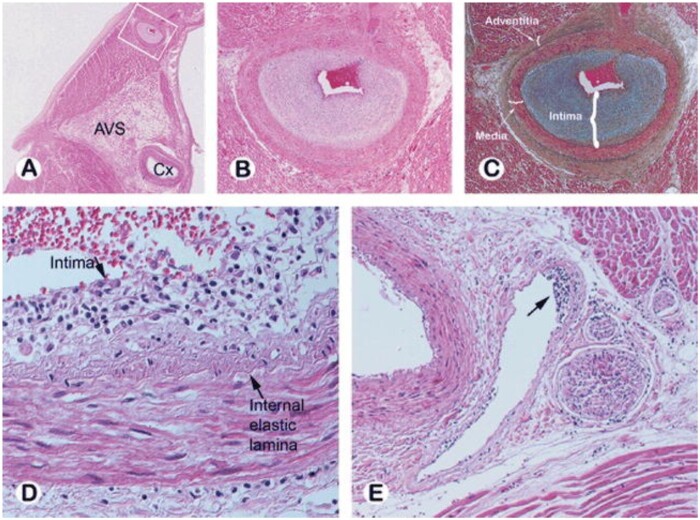

Figure 1.

Histopathology of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. (A) Photomicrograph of the left atrium and ventricle with the left circumflex (Cx) artery noted at the atrioventricular sulcus (AVS) from a patient who died of CAV 3 years post-transplant. (B, C) Intramyocardial branch of circumflex artery (from inset A) supplying the atrium shows marked intimal proliferation with preservation of the elastic lamina and normal medial layer [haematoxylin-eosin (B) and Movat pentachrome (C)]. (D, E) Subendothelial lymphocytic infiltration is seen in a small epicardial artery (D) and in an intramyocardial vein (arrow E). Reprinted with permission from Ref.143

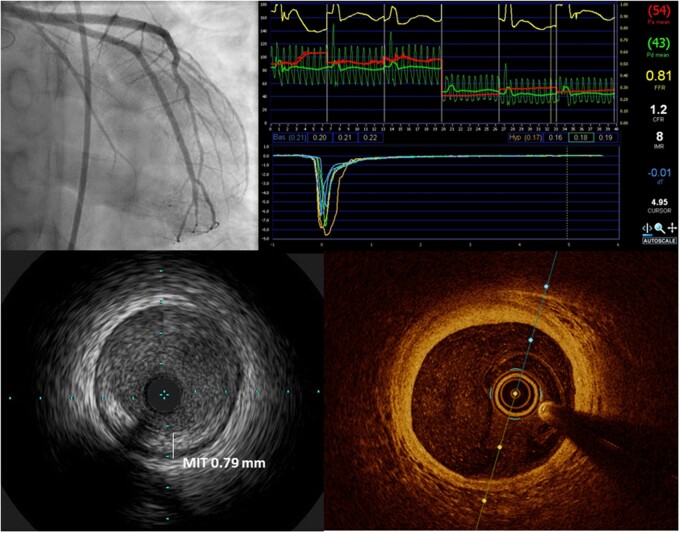

Figure 2.

Invasive coronary imaging for CAV assessment: coronary angiography is the current gold standard for identifying epicardial disease and grading severity (top left); coronary physiologic measurements including coronary flow reserve, index of microcirculatory resistance and fractional flow reserve (top right) provide functional information on epicardial and microvascular disease; intracoronary imaging using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS, bottom left) or optical coherence tomography (OCT, bottom right) enables detailed imaging of the coronary intima to detect early intimal hyperplasia as well as plaque characterization.

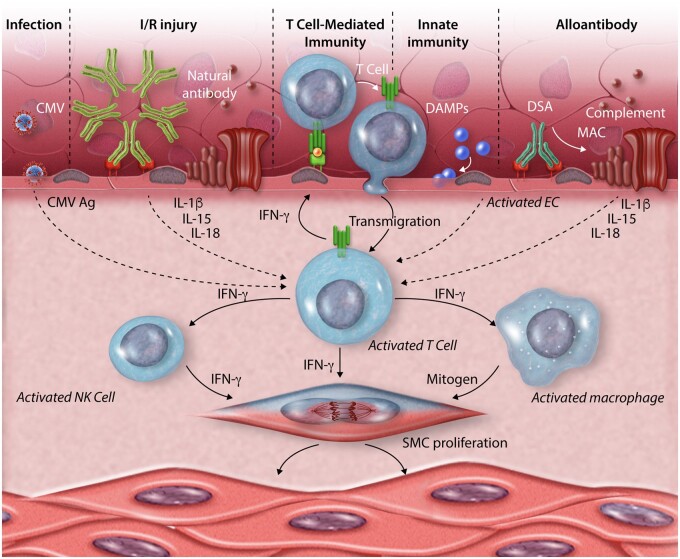

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of pathogenic mechanisms that lead to CAV. T cells that recognize graft antigens expressed on the endothelium are central to the process. These cells may undergo transmigration into the graft in response to antigen recognition or to chemokines made by and expressed on the endothelial cell surface in response to activating signals such as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) as part of an innate immune response. Endothelium may also be activated by IgG donor specific alloantibodies or by natural antibodies, the latter targeting antigens exposed following ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. These antibody responses are mediated by proteins of the complement system that form membrane attack complexes (MACs). Other sources of antigens (Ag) that stimulate T cells can come from infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV). The T-cell response is augmented by cytokines produced by the activate endothelial cells such as interleukins (IL)-1β, IL-15 or IL-18. Cytokines produced by the activated T cells within the vessel wall, notably IFN-γ but likely others as well, induce smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation and also activate infiltrating natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages to make additional mitogens that also drive intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation and matrix deposition. The net effect is the expand the vessel intima and comproimise the lumen.

9.2 Prevention/treatment

There are several strategies for the prevention and treatment of CAV that might be of value to stall the pathological remodelling which include anti-thrombotic therapy, and newer immunosuppression approaches which include costimulation blockade and anti-IL6 monoclonal antibodies, and further cholesterol-lowering strategies.

Several studies have demonstrated in heart transplant patients an increased in vitro reactivity of platelets characterized by increased expression of activated immunological surface markers as well as increased activity upon stimulation.149,150 Platelets are mediators of coronary thrombosis, endothelial injury, and inflammation that are interrelated pathogenic processes underlying CAV. Platelet aggregation is also increased in HT patients and associated with adverse cardiac events.150–152 Experimental studies have shown platelet inhibition reduces development and progression of CAV.153,154 Single-centre observational analyses demonstrate lower risk of developing angiographic CAV and reduced mortality with aspirin commenced early in the first year of transplant.155,156 A meta-analysis of 6 studies with 1911 patients concluded aspirin may reduce the development of CAV (relative risk 0.75, 95% confidence interval: 0.44–1.29) with low certainty of evidence due to the included studies having modest patient numbers, being single-centre and observational.157 Kim et al.155 studied 120 HT patients with a high burden of risk factors for CAV. Among patients receiving aspirin, there was a lower incidence of moderate to severe CAV on angiographic follow-up at 5 years. In another single-centre study, 97 patients given aspirin in the first month after transplant was compared with no aspirin treatment in 109 patients at 15 years of follow-up.156 The rate of CAV was six-fold lower in patients treated with aspirin compared with the non-treated patients (7% vs 37%).156 From other studies, there is an early data from animal studies that clopidogrel therapy can reduce the development of CAV.153,158 The combination of clopidogrel and everolimus has been also shown to significantly reduce the development of transplant arteriosclerosis in murine aortic allografts.159 It is not known if randomized clinical trials of other anti-platelet therapies with more potent P2Y12 inhibitors will corroborate the findings from the above studies. For the now, aspirin is the only prophylactic anti-platelet agent indicated for the heart transplant patient.

The immune response after transplantation that leads, on certain occasions, to graft rejection is guided by the adaptive immune response through the action of T and B lymphocytes. The adaptive immune response generally requires three signals: the antigen-specific receptors (T-cell receptor and B-cell receptor), costimulation through various pathways, and cytokines that promote both autocrine and paracrine signalling. The interaction between antigen presenting cells and host T cells, leads to the activation of a continuous cycle of inflammatory response that feeds upon itself. By using monoclonal antibodies to block costimulation of the molecular target, it was possible to find various therapeutic options for the manipulation of adaptive immune responses that could potentially suppress allograft rejection and pathological remodelling with fewer off-target effects than other immunosuppressive strategies. Attesting to this, findings from a sub-study in a kidney transplant study with costimulation blockade using belatacept (BENEFIT Trial160) suggested that renal biopsies under belatacept based immunosuppression are enriched in regulatory cells (e.g. Tregs, Bregs, plasmacytoid DCs), have lower percentages of proinflammatory cells (e.g. Th17, M1 macrophages), and less histological fibrosis.161 These findings lend credence to the hypothesis that belatacept-based immunosuppression will reduce fibrogenic pathways after heart transplant thereby decreasing CAV and graft dysfunction, ultimately improving long-term outcomes. A heart transplant clinical trial is currently being organized through the NIH (NIH R34 Grant, 2020–21).

IL-6 is upregulated after brain death promoting a proinflammatory state within the organ even prior to transplantation.162 Following transplantation, IRI associated with cold, static preservation leads to further increases in intragraft IL-6 levels.163 IL-6 subsequently increases the level of adhesion molecules, inflammatory cytokines (IL-17, IFN-γ), and molecules that regulate migration, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in endothelial cells.164 Blocking IL-6 has been shown to mitigate the pro-inflammatory milieu associated with brain death and IRI165 which could play an important role in the treatment of preventing CAV. In a kidney transplant study, tocilizumab (8 mg/kg monthly, maximal dose 800 mg, for 6–25 months) was administered to over 36 DSA+ patients with standard treatment-resistant AMR, with or without transplant glomerulopathy.166 Compared to standard of care (SOC), tocilizumab treatment reduced DSA levels and improved graft survival and long-term outcomes in patients with the severest forms of AMR. Furthermore, the drug was well tolerated without significant AEs or SAE. By altering upstream differentiation of alloreactive lymphocytes,167 promoting the generation of Tregs,168 blocking immunoglobulin synthesis, and reducing downstream aspects of the inflammatory cascade,169 IL-6 signalling inhibition may provide a novel therapeutic option in diminishing IRI, abrogating ACR and AMR, and preventing late CAV and fibrosis. An NIH randomized trial (NCT0364467) of tocilizumab in heart transplantation is currently enrolling patients to assess its efficacy in both acute and chronic rejection.

High LDL-cholesterol has been noted to be a significant risk factor for the development of CAV. This risk factor was found to be a significant independent variable to contribute to the trajectory of CAV development.25 Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a circulating protein that increases the degradation of low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLR). Inhibition of PCSK-9 results in LDLR recycling and increased hepatic clearance of circulating LDL cholesterol. The use of this drug for post-heart transplant patients is being studied. In early reports, it was well tolerated, had good results and may become an option in the prevention and treatment of CAV.170

Treatment for microvasculopathy form of CAV has not been established. By the time of diagnosis, patients not uncommonly have significant restrictive cardiac physiology and if appropriate will require retransplantation as the only option. Seeking definitive therapy for CAV will begin with further understanding of its pathogenesis. Detailed mechanistic studies are needed to find early triggers of the inflammatory pathway that leads to the development of CAV. Finally, ameliorating the injury pathways in the donor with immunosuppressive therapy might help to reduce early pathological remodelling. We await the results of current clinical trials and the advent of future therapies to prevent and treat CAV.

10. Conclusions

In this review, we have summarized the clinical significance and the state of our understanding of the processes that drive CAV, current approaches to therapy and specific near term targets for future clinical research. While there has been some improvement in prevention and treatment, CAV still poses a significant problem for cardiac transplantation therapy. Therefore, it is worth raising some possible approaches for diagnosis and treatment that are not ready for application, but offer potential directions for future advances. On the diagnostic side, there is the potential for developing more accurate and specific blood tests by analysing new types of biomarkers. We noted that both circulating proteins and nucleic acids are being tested as possible biomarkers in current research. Circulating exosomes or microparticles may reveal more specific information as they can be linked to specific cell types. In combination with advances in non-invasive imaging, it has become much easier to identify patients at risk for early intervention. On the prevention/treatment side, new immunological targets, such as the cells of innate immunity, may be introduced as complements to targeting adaptive immune cells. In addition, genetic manipulation is moving increasingly close to the clinic. In combination with pre-transplant ex vivo perfusion, genetic, or epigenetic alterations of the coronary vasculature with techniques like CRISPR/Cas may be used to render allograft vessels resistant to the pathogenic processes that drive vasculopathy. Potential targets could be reduction of endothelial stimulation of or responses to immune effector cells and molecules. Additionally, selective targeting of smooth muscle cells could stabilize a normal ‘contractile’ phenotype and prevent acquisition of a proliferative/synthetic characteristics. As noted in the introduction, lesions similar to CAV develop in some other types of vascularized allografts where they similarly contribute to progressive graft loss. In this sense, cardiac transplantation research is important for broader improvements in organ replacement therapies.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [HL109420 to J.S.P., U01AI132895 to J.S.P., R01 HL146723 to G.T., R01 HL152197 to G.T., U01AI132895 to G.T., P01HL018646 to J.C.M., P01AI123086 to J.C.M., U01AI131470 to J.C.M., R01AI165879 to J.C.M.] and by a Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada Ontario Clinician Scientist Phase I award and a Tier 2 University of Ottawa Clinical Research Chair in Cardiac Transplantation (to S.C.).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Contributor Information

Jordan S Pober, Department of Immunobiology, Pathology and Dermatology, Yale School of Medicine, 10 Amistad Street, New Haven CT 06520-8089, USA.

Sharon Chih, Division of Cardiology, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Jon Kobashigawa, Department of Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Joren C Madsen, Division of Cardiac Surgery and Center for Transplantation Sciences, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

George Tellides, Department of Surgery (Cardiac Surgery), Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

References

- 1. Bruno S, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Transplant renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kollar B, Kamat P, Klein HJ, Waldner M, Schweizer R, Plock JA. The significance of vascular alterations in acute and chronic rejection for vascularized composite allotransplantation. J Vasc Res 2019;56:163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harifi G, Nour-Eldine W, Noureldine MHA, Berjaoui MB, Kallas R, Khoury R, Uthman I, Al-Saleh J, Khamashta MA. Arterial stenosis in antiphospholipid syndrome: update on the unrevealed mechanisms of an endothelial disease. Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gori T. Coronary vasculitis. Biomedicines 2021;9: 622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, Harhay MO, Hayes D Jr, Hsich E, Meiser B, Potena L, Robinson A, Rossano JW, Sadavarte A, Singh TP, Zuckermann A, Stehlik J; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-sixth adult heart transplantation report - 2019; focus theme: donor and recipient size match. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chih S, Chong AY, Mielniczuk LM, Bhatt DL, Beanlands RS. Allograft vasculopathy: the achilles' heel of heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:80–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mehra MR. The scourge and enigmatic journey of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1291–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moayedi Y, Fan CPS, Cherikh WS, Stehlik J, Teuteberg JJ, Ross HJ, Khush KK. Survival outcomes after heart transplantation: does recipient sex matter? Circ Heart Fail 2019;12:e006218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tremblay-Gravel M, Racine N, de Denus S, Ducharme A, Pelletier GB, Giraldeau G, Liszkowski M, Parent MC, Carrier M, Fortier A, White M. Changes in outcomes of cardiac allograft vasculopathy over 30 years following heart transplantation. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagji AS, Hranjec T, Swenson BR, Kern JA, Bergin JD, Jones DR, Kron IL, Lau CL, Ailawadi G. Donor age is associated with chronic allograft vasculopathy after adult heart transplantation: implications for donor allocation. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsai FC, Marelli D, Bresson J, Gjertson D, Kermani R, Patel J, Kobashigawa JA, Laks H; UCLA Heart Transplant Group. Use of hearts transplanted from donors with atraumatic intracranial bleeds. J Heart Lung Transplant 2002;21:623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day JD, Rayburn BK, Gaudin PB, Baldwin WM 3rd, Lowenstein CJ, Kasper EK, Baughman KL, Baumgartner WA, Hutchins GM, Hruban RH. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: the central pathogenetic role of ischemia-induced endothelial cell injury. J Heart Lung Transplant 1995;14:S142–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schroeder JS, Gao SZ, Alderman EL, Hunt SA, Johnstone I, Boothroyd DB, Wiederhold V, Stinson EB. A preliminary study of diltiazem in the prevention of coronary artery disease in heart-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 1993;328:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehra MR, Ventura HO, Smart FW, Collins TJ, Ramee SR, Stapleton DD. An intravascular ultrasound study of the influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium entry blockers on the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:853–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erinc K, Yamani MH, Starling RC, Crowe T, Hobbs R, Bott-Silverman C, Rincon G, Young JB, Feng J, Cook DJ, Smedira N, Tuzcu EM. The effect of combined angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and calcium antagonism on allograft coronary vasculopathy validated by intravascular ultrasound. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raichlin ER, McConnell JP, Lerman A, Kremers WK, Edwards BS, Kushwaha SS, Clavell AL, Rodeheffer RJ, Frantz RP. Systemic inflammation and metabolic syndrome in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26:826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valantine H, Rickenbacker P, Kemna M, Hunt S, Chen YD, Reaven G, Stinson EB. Metabolic abnormalities characteristic of dysmetabolic syndrome predict the development of transplant coronary artery disease: a prospective study. Circulation 2001;103:2144–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eich D, Thompson JA, Ko DJ, Hastillo A, Lower R, Katz S, Katz M, Hess ML. Hypercholesterolemia in long-term survivors of heart transplantation: an early marker of accelerated coronary artery disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 1991;10:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobashigawa JA, Kasiske BL. Hyperlipidemia in solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 1997;63:331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kapadia SR, Nissen SE, Ziada KM, Rincon G, Crowe TD, Boparai N, Young JB, Tuzcu EM. Impact of lipid abnormalities in development and progression of transplant coronary disease: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobashigawa JA, Katznelson S, Laks H, Johnson JA, Yeatman L, Wang XM, Chia D, Terasaki PI, Sabad A, Cogert GA, Trosian K, Hamilton MA, Moriguchi JD, Kawata N, Hage A, Drinkwater DC, Stevenson LW. Effect of pravastatin on outcomes after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med 1995;333:621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grattan MT, Moreno-Cabral CE, Starnes VA, Oyer PE, Stinson EB, Shumway NE. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with cardiac allograft rejection and atherosclerosis. JAMA 1989;261:3561–3566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao SZ, Hunt SA, Schroeder JS, Alderman EL, Hill IR, Stinson EB. Early development of accelerated graft coronary artery disease: risk factors and course. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loebe M, Schüler S, Zais O, Warnecke H, Fleck E, Hetzer R. Role of cytomegalovirus infection in the development of coronary artery disease in the transplanted heart. J Heart Transplant 1990;9:707–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loupy A, Coutance G, Bonnet G, Van Keer J, Raynaud M, Aubert O, Bories MC, Racapé M, Yoo D, Duong Van Huyen JP, Bruneval P, Taupin JL, Lefaucheur C, Varnous S, Leprince P, Guillemain R, Empana JP, Levine R, Naesens M, Patel JK, Jouven X, Kobashigawa J. Identification and characterization of trajectories of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation: a population-based study. Circulation 2020;141:1954–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goekler J, Zuckermann A, Kaider A, Angleitner P, Osorio-Jaramillo E, Moayedifar R, Uyanik-Uenal K, Kainz FM, Masetti M, Laufer G, Aliabadi-Zuckermann AZ. Diminished impact of cytomegalovirus infection on graft vasculopathy development in the antiviral prophylaxis era - a retrospective study. Transpl Int 2018;31:909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klimczak-Tomaniak D, Roest S, Brugts JJ, Caliskan K, Kardys I, Zijlstra F, Constantinescu AA, Voermans JJC, van Kampen JJA, Manintveld OC. The association between cytomegalovirus infection and cardiac allograft vasculopathy in the era of antiviral valganciclovir prophylaxis. Transplantation 2020;104:1508–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Russell PS, Chase CM, Winn HJ, Colvin RB. Coronary atherosclerosis in transplanted mouse hearts. II. Importance of humoral immunity. J Immunol 1994;152:5135–5141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirohashi T, Uehara S, Chase CM, DellaPelle P, Madsen JC, Russell PS, Colvin RB. Complement independent antibody-mediated endarteritis and transplant arteriopathy in mice. Am J Transplant 2010;10:510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hirohashi T, Chase CM, Della Pelle P, Sebastian D, Alessandrini A, Madsen JC, Russell PS, Colvin RB. A novel pathway of chronic allograft rejection mediated by NK cells and alloantibody. Am J Transplant 2012;12:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Topilsky Y, Gandhi MJ, Hasin T, Voit LL, Raichlin E, Boilson BA, Schirger JA, Edwards BS, Clavell AL, Rodeheffer RJ, Frantz RP, Kushwaha SS, Lerman A, Pereira NL. Donor-specific antibodies to class II antigens are associated with accelerated cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a three-dimensional volumetric intravascular ultrasound study. Transplantation 2013;95:389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Loupy A, Toquet C, Rouvier P, Beuscart T, Bories MC, Varnous S, Guillemain R, Pattier S, Suberbielle C, Leprince P, Lefaucheur C, Jouven X, Bruneval P, Duong Van Huyen JP. Late failing heart allografts: pathology of cardiac allograft vasculopathy and association with antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 2016;16:111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith JD, Banner NR, Hamour IM, Ozawa M, Goh A, Robinson D, Terasaki PI, Rose ML. De novo donor HLA-specific antibodies after heart transplantation are an independent predictor of poor patient survival. Am J Transplant 2011;11:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalache S, Dinavahi R, Pinney S, Mehrotra A, Cunningham MW, Heeger PS. Anticardiac myosin immunity and chronic allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients. J Immunol 2011;187:1023–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Azimzadeh AM, Pfeiffer S, Wu GS, Schröder C, Zhou H, Zorn GL 3rd, Kehry M, Miller GG, Rose ML, Pierson RN 3rd. Humoral immunity to vimentin is associated with cardiac allograft injury in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant 2005;5:2349–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jurcevic S, Ainsworth ME, Pomerance A, Smith JD, Robinson DR, Dunn MJ, Yacoub MH, Rose ML. Antivimentin antibodies are an independent predictor of transplant-associated coronary artery disease after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation 2001;71:886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raichlin E, Edwards BS, Kremers WK, Clavell AL, Rodeheffer RJ, Frantz RP, Pereira NL, Daly RC, McGregor CG, Lerman A, Kushwaha SS. Acute cellular rejection and the subsequent development of allograft vasculopathy after cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009;28:320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eskander MA, Adler E, Hoffmayer KS. Arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in post-cardiac transplant patients. Curr Opin Cardiol 2020;35:308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nikolova AP, Kobashigawa JA. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: the enduring enemy of cardiac transplantation. Transplantation 2019;103:1338–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Konerman MC, Lazarus JJ, Weinberg RL, Shah RV, Ghannam M, Hummel SL, Corbett JR, Ficaro EP, Aaronson KD, Colvin MM, Koelling TM, Murthy VL. Reduced myocardial flow reserve by positron emission tomography predicts cardiovascular events after cardiac transplantation. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kransdorf EP, Kobashigawa JA. Biomarkers for cardiac allograft vasculopathy: still searching after all these years. Transplantation 2017;101:28–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin D, Cohen Freue G, Hollander Z, John Mancini GB, Sasaki M, Mui A, Wilson-McManus J, Ignaszewski A, Imai C, Meredith A, Balshaw R, Ng RT, Keown PA, Robert McMaster W, Carere R, Webb JG, McManus BM; Networks of Centres of Excellence, Centres of Excellence for Commercialization and Research-Prevention of Organ Failure Centre of Excellence. Plasma protein biosignatures for detection of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shaw SM, Williams SG. Is brain natriuretic peptide clinically useful after cardiac transplantation? J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:1396–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Labarrere CA, Lee JB, Nelson DR, Al-Hassani M, Miller SJ, Pitts DE. C-reactive protein, arterial endothelial activation, and development of transplant coronary artery disease: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;360:1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Di Francesco A, Fedrigo M, Santovito D, Natarelli L, Castellani C, De Pascale F, Toscano G, Fraiese A, Feltrin G, Benazzi E, Nocco A, Thiene G, Valente M, Valle G, Schober A, Gerosa G, Angelini A. MicroRNA signatures in cardiac biopsies and detection of allograft rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:1329–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Singh N, Heggermont W, Fieuws S, Vanhaecke J, Van Cleemput J, De Geest B. Endothelium-enriched microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:1376–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Neumann A, Napp LC, Kleeberger JA, Benecke N, Pfanne A, Haverich A, Thum T, Bara C. MicroRNA 628-5p as a novel biomarker for cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Transplantation 2017;101:e26–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Young JB, Windsor NT, Kleiman NS, Lowry R, Cocanougher B, Lawrence EC. The relationship of soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels to allograft arteriopathy after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992;11:S79–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Przybylek B, Boethig D, Neumann A, Borchert-Moerlins B, Daemen K, Keil J, Haverich A, Falk C, Bara C. Novel cytokine score and cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stehlik J, Armstrong B, Baran DA, Bridges ND, Chandraker A, Gordon R, De Marco T, Givertz MM, Heroux A, Iklé D, Hunt J, Kfoury AG, Madsen JC, Morrison Y, Feller E, Pinney S, Tripathi S, Heeger PS, Starling RC. Early immune biomarkers and intermediate-term outcomes after heart transplantation: results of clinical trials in organ transplantation-18. Am J Transplant 2019;19:1518–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu Z, Colovai AI, Tugulea S, Reed EF, Fisher PE, Mancini D, Rose EA, Cortesini R, Michler RE, Suciu-Foca N. Indirect recognition of donor HLA-DR peptides in organ allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 1996;98:1150–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee RS, Yamada K, Houser SL, Womer KL, Maloney ME, Rose HS, Sayegh MH, Madsen JC. Indirect recognition of allopeptides promotes the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:3276–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hornick PI, Mason PD, Baker RJ, Hernandez-Fuentes M, Frasca L, Lombardi G, Taylor K, Weng L, Rose ML, Yacoub MH, Batchelor R, Lechler RI. Significant frequencies of T cells with indirect anti-donor specificity in heart graft recipients with chronic rejection. Circulation 2000;101:2405–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sayegh MH. Why do we reject a graft? Role of indirect allorecognition in graft rejection. Kidney Int 1999;56:1967–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weis M, von Scheidt W. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a review. Circulation 1997;96:2069–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kosek JC, Bieber C, Lower RR. Heart graft arteriosclerosis. Transplant Proc 1971;3:512–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bieber CP, Stinson EB, Shumway NE, Payne R, Kosek J. Cardiac transplantation in man. VII. Cardiac allograft pathology. Circulation 1970;41:753–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Billingham ME. Histopathology of graft coronary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992;11:S38–S44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lu WH, Palatnik K, Fishbein GA, Lai C, Levi DS, Perens G, Alejos J, Kobashigawa J, Fishbein MC. Diverse morphologic manifestations of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a pathologic study of 64 allograft hearts. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rahmani M, Cruz RP, Granville DJ, McManus BM. Allograft vasculopathy versus atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2006;99:801–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pethig K, Heublein B, Wahlers T, Haverich A. Mechanism of luminal narrowing in cardiac allograft vasculopathy: inadequate vascular remodeling rather than intimal hyperplasia is the major predictor of coronary artery stenosis. Working Group on Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy. Am Heart J 1998;135:628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mainigi SK, Goldberg LR, Sasseen BM, See VY, Wilensky RL. Relative contributions of intimal hyperplasia and vascular remodeling in early cardiac transplant-mediated coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Okada K, Kitahara H, Yang HM, Tanaka S, Kobayashi Y, Kimura T, Luikart H, Yock PG, Yeung AC, Valantine HA, Fitzgerald PJ, Khush KK, Honda Y, Fearon WF. Paradoxical vessel remodeling of the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery predicts long-term mortality after heart transplantation. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:942–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang Y, Bai Y, Qin L, Zhang P, Yi T, Teesdale SA, Zhao L, Pober JS, Tellides G. Interferon-gamma induces human vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal expansion by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dependent mammalian target of rapamycin raptor complex 1 activation. Circ Res 2007;101:560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Keogh A, Richardson M, Ruygrok P, Spratt P, Galbraith A, O'Driscoll G, Macdonald P, Esmore D, Muller D, Faddy S. Sirolimus in de novo heart transplant recipients reduces acute rejection and prevents coronary artery disease at 2 years: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation 2004;110:2694–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fish RD, Nabel EG, Selwyn AP, Ludmer PL, Mudge GH, Kirshenbaum JM, Schoen FJ, Alexander RW, Ganz P. Responses of coronary arteries of cardiac transplant patients to acetylcholine. J Clin Invest 1988;81:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Davis SF, Yeung AC, Meredith IT, Charbonneau F, Ganz P, Selwyn AP, Anderson TJ. Early endothelial dysfunction predicts the development of transplant coronary artery disease at 1 year posttransplant. Circulation 1996;93:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yang HM, Khush K, Luikart H, Okada K, Lim HS, Kobayashi Y, Honda Y, Yeung AC, Valantine H, Fearon WF. Invasive assessment of coronary physiology predicts late mortality after heart transplantation. Circulation 2016;133:1945–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Salomon RN, Hughes CC, Schoen FJ, Payne DD, Pober JS, Libby P. Human coronary transplantation-associated arteriosclerosis. Evidence for a chronic immune reaction to activated graft endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 1991;138:791–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. van Loosdregt J, van Oosterhout MF, Bruggink AH, van Wichen DF, van Kuik J, de Koning E, Baan CC, de Jonge N, Gmelig-Meyling FH, de Weger RA. The chemokine and chemokine receptor profile of infiltrating cells in the wall of arteries with cardiac allograft vasculopathy is indicative of a memory T-helper 1 response. Circulation 2006;114:1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Huibers M, De Jonge N, Van Kuik J, Koning ES, Van Wichen D, Dullens H, Schipper M, De Weger R. Intimal fibrosis in human cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Transpl Immunol 2011;25:124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wehner JR, Fox-Talbot K, Halushka MK, Ellis C, Zachary AA, Baldwin WM 3rd. B cells and plasma cells in coronaries of chronically rejected cardiac transplants. Transplantation 2010;89:1141–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cuffy MC, Silverio AM, Qin L, Wang Y, Eid R, Brandacher G, Lakkis FG, Fuchs D, Pober JS, Tellides G. Induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in vascular smooth muscle cells by interferon-gamma contributes to medial immunoprivilege. J Immunol 2007;179:5246–5254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Atkinson C, Horsley J, Rhind-Tutt S, Charman S, Phillpotts CJ, Wallwork J, Goddard MJ. Neointimal smooth muscle cells in human cardiac allograft coronary artery vasculopathy are of donor origin. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004;23:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Minami E, Laflamme MA, Saffitz JE, Murry CE. Extracardiac progenitor cells repopulate most major cell types in the transplanted human heart. Circulation 2005;112:2951–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bundy RE, Marczin N, Birks EF, Chester AH, Yacoub MH. Transplant atherosclerosis: role of phenotypic modulation of vascular smooth muscle by nitric oxide. Gen Pharmacol 2000;34:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, Swiatlowska P, Newman AA, Greene ES, Straub AC, Isakson B, Randolph GJ, Owens GK. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat Med 2015;21:628–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chen PY, Qin L, Li G, Malagon-Lopez J, Wang Z, Bergaya S, Gujja S, Caulk AW, Murtada SI, Zhang X, Zhuang ZW, Rao DA, Wang G, Tobiasova Z, Jiang B, Montgomery RR, Sun L, Sun H, Fisher EA, Gulcher JR, Fernandez-Hernando C, Humphrey JD, Tellides G, Chittenden TW, Simons M. Smooth muscle cell reprogramming in aortic aneurysms. Cell Stem Cell 2020;26:542–557.e511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Allahverdian S, Chehroudi AC, McManus BM, Abraham T, Francis GA. Contribution of intimal smooth muscle cells to cholesterol accumulation and macrophage-like cells in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 2014;129:1551–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kovacic JC, Dimmeler S, Harvey RP, Finkel T, Aikawa E, Krenning G, Baker AH. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition in cardiovascular disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:190–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu SP, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident Sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:9349–9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen PY, Qin L, Barnes C, Charisse K, Yi T, Zhang X, Ali R, Medina PP, Yu J, Slack FJ, Anderson DG, Kotelianski V, Wang F, Tellides G, Simons M. FGF regulates TGF-β signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via control of let-7 miRNA expression. Cell Rep 2012;2:1684–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McCallinhart PE, Scandling BW, Trask AJ. Coronary remodeling and biomechanics: are we going with the flow in 2020? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2021;320:H584–H592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]