Abstract

In the code of public health, misuse is defined as intentional and inappropriate use of a medicine or product, which is not in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorisation or the registration as well as with good practice recommendations. Very often this involves an individual or the interaction of several individuals including the patient, his/her carers, prescriber(s) and/or dispensers. Misuse is common; it is the source of medicinal adverse effects for which a significant part is avoidable. Medicines initially prescribed or dispensed in the context of their marketing authorization (MA) can also be the subject of primary dependency and misappropriation. Companies which develop medicines nationally make declarations to the ANSM (French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products) and implement measures to limit non-compliant use of their products. Recently, the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted the influence and societal impact of drug misuse. The finding of the existence of systemic misuse, the impossibility of proposing simple solutions leads us to propose two main areas for improved information and the training of users and health professionals in medicines in the context of multi-faceted interventions: prevention of misuse on the one hand and its identification and treatment on the other hand.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019

Keywords: Misuse, Drug, Marketing authorisation, Training, Information

Abbreviations

- ANSM

Agence nationale de sécurité des médicaments et des produits de santé (French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products)

- MA

marketing authorization

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease-2019

Definitions

Misuse can be globally defined as intentional and inappropriate use which is not compliant with the terms of the marketing authorization (MA – with respect to the indication, route of administration, dosage or duration of treatment) as well as with good practice recommendations. In their 2013 report on the monitoring and promotion of the proper use of medicines, Begaud and Costagliola defined the proper use of medicines as the set of conditions ensuring, for a medicine or a class of medicines, on both an individual and societal level, optimized risk/benefit and cost/efficacy ratios [1].

The global notion of misuse in the literature is extremely heterogeneous [2]. If one limits the analysis to sources which are applicable in France, there are subtle differences in definition and context, detailed in Table 1 . Misuse should be distinguished from other similar notions. The notion of a medication error is essentially non-intentional. The notion of abuse covers excessive use but can be the consequence of compliant prescription and dispensing [3].

Table 1.

Respective definitions of misuse, drug error, abuse and overdose according to sources.

| Code of public health Article R5121-152 [18] | ANSM – Good Pharmacovigilance Practices 2018 [19] | EMA – Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices Annex I (Rev. 4 – 2017) [20] |

|---|---|---|

| Misuse | Mésusage (Misuse) | Misuse of a medicinal product |

| Intentional and inappropriate use of a medicine or a product, which is not compliant with the marketing authorisation or registration as well as with good practice recommendations | Use which is not compliant with the terms of the authorisation (MA, TUA, PIA), the registration or temporary use recommendation (TUR) and with good practice recommendations, intentional with a medical purpose and which is inappropriate | Situations where a medicinal product is intentionally and inappropriately used not in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorisation |

| Misuse for illegal purpose | Misuse of a medicinal product for illegal purposes | |

| Consumption of a medicine for recreational purposes, as well as its prescription, its sale or any other use for fraudulent or lucrative purposes | Misuse for illegal purposes is misuse with the additional connotation of an intention of misusing the medicinal product to cause an effect in another person. This includes, amongst others: the sale, to other people, of medicines for recreational purposes and use of a medicinal product to facilitate assault | |

| Off label use | Off-label use | |

| Use which is not compliant with an authorisation (MA, TUA, PIA) or a temporary use recommendation (TUR) or a registration, which is intentional and appropriate with respect to data acquired from science | Situations where a medicinal product is intentionally used for a medical purpose not in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorization | |

| Examples include the intentional use of a product in situations other than the ones described in the authorised product information, such as a different indication in terms of medical condition, a different group of patients (e.g. a different age group), a different route or method of administration or a different posology. The reference terms for off-label use are the terms of marketing authorisation in the country where the product is used | ||

| Drug error | Drug error | Medication error |

| A non-intentional error by a health professional, patient or third party, as applicable, occurring during the care process involving a medicine or health product mentioned in article R.5121-150, in particular at the time of the prescription, dispensing or administration | Non-intentional omission or performance of a procedure during the care process involving a medicine, which can be the source of a risk or adverse event for the patient. The drug error can be proven or potential (intercepted before administration to the patient) | An unintended failure in the drug treatment process that leads to, or has the potential to lead to, harm to the patient (see EMA-PRAC Good Practice Guide on Recording, Coding, Reporting and Assessment of Medication Errors, 23 October 2015) |

| Abuse | Drug abuse | Abuse of a medicinal product |

| Excessive, intentional use, either persistent or sporadic, of medicines or products mentioned in article R.5121-150, accompanied by harmful physical or psychological reactions | Excessive, intentional use, either persistent or sporadic of medicines, accompanied by harmful physical or psychological reactions | Persistent or sporadic, intentional excessive use of medicinal products which is accompanied by harmful physical or psychological effects [DIR 2001/83/EC Art 1(16)] |

| Overdose | Overdose | Overdose |

| Administration of a quantity of medicine or product, quantity per intake or cumulative greater than the maximum recommended dose in the summary of product characteristics mentioned in article R.5121-1 | Administration of a quantity of medicine or product, quantity per intake or cumulative, greater than the maximum recommended dose in the SPC. In practice, it is exposure resulting in high plasmatic concentrations. It could be the excessive (intentional or accidental) taking of a medicine | Administration of a quantity of a medicinal product given per administration or cumulatively which is above the maximum recommended dose according to the authorised product information |

| When applying this definition, clinical judgement should always be applied |

General context

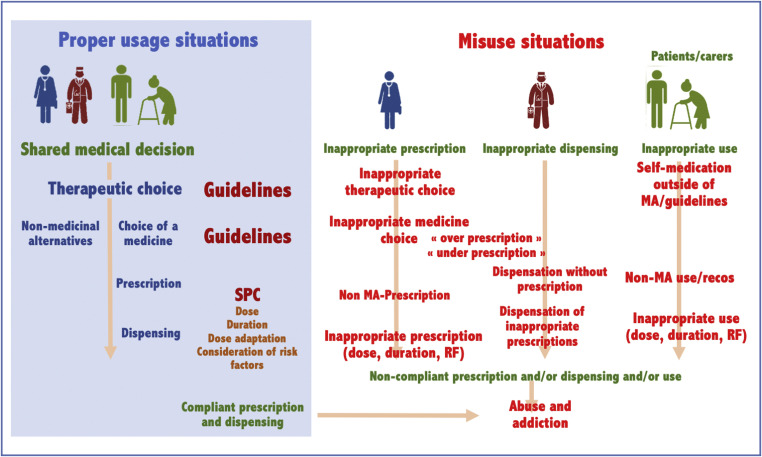

Misuse of a medicine involves various parameters represented schematically in Fig. 1 . Most often interaction between several individuals is involved including the patient, his/her carers, the prescriber(s) and/or dispensers; an intention (the absence of intentionality being characteristic of a medication error) and the objective for the patient (either therapeutic or not). This is in a context in which misuse of a medicine occurs. This context will depend on the existence or non-existence of therapeutic medicine or non-medicine choices depending on the patient's clinical condition, compliance with the summary of product characteristics in terms of dose, duration, and dose adaptation if the condition exists (example of non-MA prescriptions in paediatrics). Finally, the consideration of iatrogenic risk factors (kidney failure, etc.) is a major element to be incorporated.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the complexity of possible situations of misuse and individuals involved. On the left “appropriate” use is simplified based on health authority standards (HAS, ANSM) or professional societies, and consistent with the summary of product characteristics. On the right, the various situations of misuse are identified with the identification of individuals. Adapted according to [1], [2], [24]. MA: marketing authorisation; FR: risk factor; RCP: summary of product characteristics

Summary of what exists

Non-MA prescription is common and is estimated to be 20% of prescriptions in Europe and in the USA [4]. France is quite a bad pupil in the European Union, being classified in a study conducted by the National Health Insurance Scheme at the top for 6 out of 9 classes studied in comparison with Germany, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom [5]. If one takes the example of psychotropic drugs, the existence of misuse is common and is easy to describe. In Europe, France is ranked 3rd for the consumption of hypnotics and 2nd for the consumption of anxiolytics [6]. In 2015, France was ranked 2nd for the consumption of benzodiazepines, behind Spain, with less consuming states being Germany and the United Kingdom. However, European consumption reduced by 5.1% between 2012 and 2015 whereas it dropped by 10% in France over the same period. Whereas in France 1/3 of people use at least one psychotropic drug over the course of their life, less than a third of those with a major depressive episode were treated with an anti-depressant according to the recommendations [7] with over 80% of hypnotics/anxiolytics prescribed for over 3 months in subjects over 65 years [8]. Also, although the prescription of psychotropic drugs is common in France, a significant part of this is not proper use.

Concept of avoidability

To date, there is no consensual definition of an avoidable drug adverse effect or a validated tool to measure avoidability. In the context of a survey of adverse effects reported to Tours CRPV from November 2002 to November 2003 [9], prescription was considered as inappropriate for 32% of the medicines involved, corresponding to 45% of patients. These drug adverse effects were considered to be wholly avoidable in 9% of cases, partially avoidable in 8% of cases and unavoidable in 83% of patients.

By using the same methodology, the French network of 31 regional pharmacovigilance centres conducted a multicentre prospective study of a random sample of 141 short-stay departments of medical specialisms in public hospitals in metropolitan France, involving patients treated between January and May 2018. In this IATROSTAT report published in November 2021 [10], the proportion of hospitalisations related to a drug adverse effect was 8.5% on average, with an increase according to age to reach 10.6% of the over 65 year olds. The extrapolation of these results enabled the authors to estimate the number of annual hospitalisations to be 212,500 related to a drug adverse effect in short-stay departments of medical specialisms in public hospitals in metropolitan France. The mortality rate after hospitalisation for a drug adverse effect, after one month of follow up, was estimated to be 1.3%, i.e. approximately 2,760 deaths per year in France. The drug adverse effect was deemed to be avoidable in 16.1% of cases of hospitalised patients [10]. The primary non-conformity situations were non compliance with the dose or duration of use (27.9%), a warning (23.2%) or precaution for use (18.6%) for a medicine involved in the drug adverse effect. There were no cases of transgression for a contra-indication. In addition, it is appropriate to note that in 11.6% of situations of non-conformity, inappropriate self-medication and misuse by the patient were the cause.

Concept of abuse and addiction

The objective of the French addiction vigilance network is to monitor all psychoactive substances with an abuse potential, including medicines and their health consequences in humans. Created in 1990 around a network of regional addiction vigilance centres covering the entire country, these pharmacologists who are experts in addiction vigilance developed an interface with various partners (doctors, [dispensing] chemists, toxicologists, specialist addiction structures…) and implemented several additional original tools for spontaneous notification. Such a multi-dimensional approach including proactive monitoring by these tools and also by several sources of heterogenous data enabled the early detection of signals and alerts for addiction vigilance involving medicines initially prescribed or dispensed in the context of their MA as shown by the inappropriate use of psychoactive medicines (codeine analgesics or H1 sedative anti-histamines on open sale) in adolescents and young adults [3] or even the issue of patients who consume an opioid analgesic to relieve pain, and who develop primary dependency on their treatment, and sometimes away from its initial indication [11].

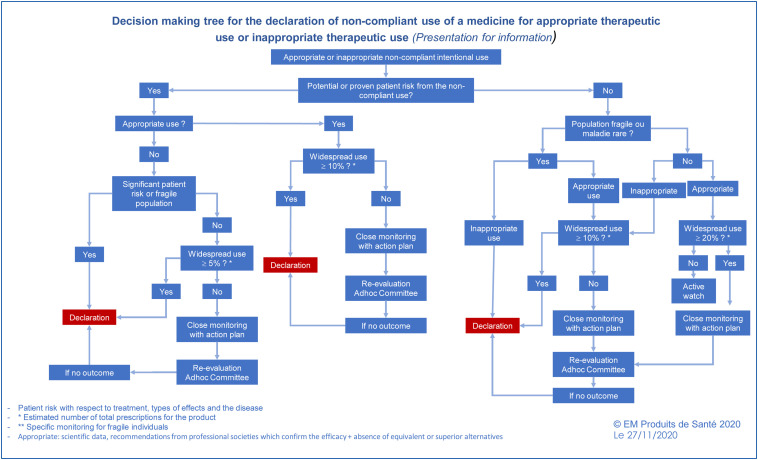

Decision-making tools. Pharmaceutical companies point of view

In France, the law dated 29 December 2011 reinforced the regulatory obligations of companies who develop a medicine nationally with respect to the declaration and implementation of measures to limit non-compliant use of their products (articles L.5121-14-3 and R.5121-164 of the code of public health). The French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (Agence nationale de sécurité du medicament et des produits de santé, ANSM) also established a reporting guide for drug companies defining expectations in terms of declaration, a guide which was updated on 22 December 2017 [12].

Reports should only involve intentional non-compliant use with a medical objective, seen nationally; this system is in addition to the risks identified in the context of risk management plans related to the MA. Reporting is particularly required when non-compliant use for which the company is aware is widespread, and/or exposes patients to a significant risk, and/or involves a fragile population or a rare disease. Risk analysis prior to reporting enables one to arrive at these conclusions. To respond to these challenges, most companies implemented a pluri-disciplinary committee in order to:

-

•

describe the non-compliant use and assess the patient risk (estimation of the number of patients involved in France, summary of existing data from the literature, congresses, pharmacovigilance, experience abroad, databases, etc. for the benefit and risk related to this use);

-

•

to develop an action plan in the event of an identified risk to limit non-compliant use (e.g.: informing medical representatives, implementing market or pharmaco-epidemiological studies, modification of the SPC/leaflet, etc.);

-

•

to monitor the actions implemented, if applicable.

This in-depth analysis will enable a company to establish whether a declaration should be made to the ANSM or not.

A decision-making tool (Fig. 2 ) was developed in the context of training for employees of pharmaceutical companies working in departments responsible for monitoring non-compliant use entitled “Non-compliant use of medicines: management and declaration”. Constructed in the form of a flowchart, this tool enables, after the evaluation of all available elements, the company to establish the required action for a given situation of non-compliant use. The flow of the flowchart which applies to any intentional non-compliant use, identified either as appropriate or inappropriate, firstly starts by determining if there is a significant, potential or proven patient risk related to this type of use thereby suggesting the existence of a potentially risky practice. It will then be determined if the use involves a fragile population or a rare disease. The confrontation of this use with the science data will distinguish appropriate uses from non-appropriate uses. The extent of this use will also be evaluated to find out if the phenomenon seen is marginal or more common by applying more restrictive alert thresholds in the event of an inappropriate nature or the identification of a patient risk or fragile population. Finally, and according to the characteristics of the use seen, for each situation, action will be proposed that could include either close monitoring with an action plan with a view to ad hoc committee re-evaluation or a declaration to the ANSM. The declaration to the ANSM will include a description of the measures taken, either ongoing or planned, by the company to limit the use seen or make it compliant via an amendment to the MA or a new approval.

Figure 2.

Decision-making tool developed in the context of training entitled “Non-compliant use of medicines: management and declaration” for employees of pharmaceutical companies working in departments responsible for monitoring non-compliant use. This tool enables companies to establish the action required for a precise situation of non-compliant use.

Misuse and society

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted the influence and societal impact of communication about medicines. The repeated communication by politicians about the potential benefits of hydroxychloroquine outside of any indication is accompanied by increased information on the internet, purchases [13], then an increase from April 2020 in notifications of adverse effects associated with the taking of hydroxychloroquine in the World Health Organisation database [14], before the final conclusion in April 2021 on excess mortality from hydroxychloroquine used in the context of COVID-19 [15]. Widescale misuse is therefore found here promoted by political personalities such as the president of the United States of America or Brazil. There is also heterogeneity in the media. In fact, most written or televised conventional media is organised with fast-checking offices for information which is easily verifiable, and large French media organisations have produced very factual analyses with respect to the proper use of medicines in the context of COVID. The term media comprises a set of very heterogeneous practices and trends. In the context of hydroxychloroquine, the media bias for the information has for example appeared clear with an excess of communication in conservative American media [13], [16].

Recommendations

The finding of the existence of systemic misuse, the impossibility of proposing simple solutions leads us to propose two main areas for improved information and the training of users and health professionals in medicines in the context of multi-faceted interventions (Table 2 ). Some of these proposals have already been proposed in the context of a report on the improvement of information for users and health professionals for medicines in 2018 [17]. The two main areas of work proposed are, on the one hand, the prevention of misuse, with significant training. The second area involves the identification and treatment of misuse, including the need to identify, make transparent and distribute in an understandable way data on misuse on a national level. In that regard, the creation of a barometer for misuse on a population level is suggested.

Table 2.

Main areas of improvement of information and training for users and health professionals for medicines. Round table recommendations.

| Prevention of misuse | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | Target audience | Suggested method | Examples |

| Education/training/general acculturation | Secondary school pupils/school pupils | Introduce medicines in primary and secondary education (topic to be introduced in the health department) | |

| Promote education to media and information | Eduscol: https://entreleslignes.media/ | ||

| Health studies’ students | Reinforce education about medicines in health studies (medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, midwifery, physiotherapy, nursing, etc.) | Medicine modules in PAS/LAS (Specific Health Access Pathway/Degree with “Health Access” option); therapeutic sessions in objective and structured clinical examinations (ECOS) in second year of studies | |

| Patients and carers | Implement university training for patient partners in patient associations; promote therapeutic education Collaborative work on patient leaflets |

University degree from the Francophone Union of Patient Partners: https://ufpp.fr/formations-de-l-ufpp.html; work on e-leaflets: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/key-principles-use-electronic-product-information-eu-medicines) | |

| General population | Train the public (open access public service training/information platform) | ||

| Information | |||

| Journalists | Promote scientific journalism within editorials | Initiative d’Epsilon: https://www.epsiloon.com/common/cms/charte | |

| Professional societies | Communicate with the wider public | Initiative from Société française de pharmacologie et de thérapeutique: https://sfpt-fr.org/covid19 | |

| Regional Pharmacovigilance Centres, Regional Addiction Vigilance Centres National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products | Promote information of professionals and patients in medicines, their adverse effects and their proper use, enable direct access for patients to information; remind professionals that the efficacy and safety of a medicine is conditional, without exception, on compliance with the SPC | https://www.rfcrpv.fr/contacter-votre-crpv; https://addictovigilance.fr/bulletin/; https://base-donnees-publique.medicaments.gouv.fr; https://ansm.sante.fr/dossiers-thematiques/covid-19-vaccins/covid-19-suivi-hebdomadaire-des-cas-deffets-indesirables-des-vaccins; https://ansm.sante.fr/dossiers-thematiques/medicaments-et-grossesse; https://ansm.sante.fr/actualites/antalgiques-opioides-lansm-publie-un-etat-des-lieux-de-la-consommation-en-france | |

| Companies | Communicate with the wider public in a concerted way with agencies | Antibiotics: proper use, medical visit charter (communication on risk minimisation measures, surveys of medical visits), escalation of non-MA cases. Monitoring of sales, monitoring of reports | |

| Identification and treatment | |||

| Identification | Networks of Regional Pharmacovigilance Centres (CRPV) and Centres for the evaluation and information on pharmacodependency and addiction vigilance (CEIP-A) | Stimulate declarations to CRPV or CEIP-A of cases of misuse, including without an adverse effect in order to detect them better | Notifications/information requests received by networks of CRPV and CEIP. Sentinel networks of CEIP (OPPIDUM device via addiction structures; OSIAP device for falsified prescriptions, etc.) Mésange Project: identification of cases of misuse at the time of pharmaceutical dispensing |

| Companies | Escalation of signals to National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products | Indicators for monitoring of sales, indicators for medical information questions | |

| Doctors and (dispensing) chemists | Structuring of shared medical record (universal access), and harmonisation with the pharmaceutical file | ||

| Hospitals | Monitoring of consumption, monitoring of supply tensions | ||

| National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products | Comparison of the number of average packs with respect to the expected number, for abuse and for non-MA prescriptions/dispenses. Highlighting of misuse via health insurance databases [21] | Detection of doctor-shopping behaviour [22] | |

| Patients | On an individual basis: Medicine conciliation; use by the doctor of tools for highlighting misuse (e.g. opioids) | ||

| Treatment | National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products | Change of prescription methods (health authorities), risk reduction measures (Agencies, commercial documents e.g. isotretinoide). Monitoring of change of prescription methods | Example with monitoring of zolpidem reports -> zopiclone for Z drugs [23] |

| Dispensing chemists | Dispensation adaptée (01/07/2020) https://uspo.fr/dad-dispensation-adaptee-liste-des-specialites/ |

To conclude, the identification and treatment of misuse is complex and cannot be based on simple measures and a single individual. Above all it requires the identification of situations at risk of misuse thanks to various networks which are already available (regional pharmacovigilance centres, pharmacodependency and addiction vigilance information and evaluation centres), training of various health professionals involved in the treatment of patients and media relay for carers and patients. Coordination of all individuals, including patients, carers and the media is therefore required. Finally, it involves the implementation of impactful measures for these prevention actions.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

The articles, analyses and proposals of the New Giens Workshops are those of the authors and do not prejudge the proposals of their organisation.

References

- 1.Bégaud B., Costagliola D. 2013. Rapport sur la surveillance et la promotion du bon usage du medicament en France. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Rapport_Begaud_Costagliola.pdf. [Accessed 21 December 2021 (57 pp.)] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singier A., Noize P., Berdaï D., et al. Medicine misuse: a systematic review and proposed hierarchical terminology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(4):1695–1704. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Micallef J., Jouanjus É., Mallaret M., Lapeyre Mestre M. Détection des signaux du réseau français d’addictovigilance : méthodes innovantes d’investigation, illustrations et utilité pour la santé publique. Therapie. 2019;74:579–590. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé . 2012. Rapport de synthèse des Assises du médicament. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/ministere/documentation-et-publications-officielles/rapports/sante/article/rapport-de-synthese-des-assises-du-medicament. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caisse nationale de l’Assurance maladie . 2007. Consommation et dépenses de médicaments : comparaison des pratiques françaises et européennes. http://www.puppem.com/documents/cnamts_consommation_depenses_med_europe_10-2007.pdf. [Accessed 21 December 2021 (14 pp.)]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.ANSM . 2017. Etat des lieux de la consommation des benzodiazepines en France. https://archiveansm.integra.fr/var/ansm_site/storage/original/application/28274caaaf04713f0c280862555db0c8.pdf. [Accessed 21 December 2021 (60 pp.)] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grolleau A., Cougnard A., Bégaud B., Verdoux H. Psychotropic drug use and correspondence with psychiatric diagnoses in the mental health in the general population survey. Encephale. 2008;34:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institut national de veille sanitaire . 2007. Rapport d’étude épidémiologique. Psychotropes Code de l’enquête (IU2007-05) https://www.sentiweb.fr/document/955. [Accessed 21 December 2021 (53 pp.)] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonville-Béra A.P., Saissi H., Bensouda-Grimaldi L., Beau-Salinas F., Cissoko H., Giraudeau B., et al. Avoidability of adverse drug reactions spontaneously reported to a french regional drug monitoring centre. Drug Saf. 2009;32:429–440. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laroche M.L., Polard E., Gautier S., Lebrun-Vignes B., Faillie J.L., Chouchana L., et al. Epidemiology of hospitalization due to adverse drug reactions in France: the IATROSTAT study [Abstract CO-009] Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2021;35(S1):14–46. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fcp.12669. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ANSM . 2019. Antalgiques opioïdes : l’ANSM publie un état des lieux de la consommation en France. https://ansm.sante.fr/actualites/antalgiques-opioides-lansm-publie-un-etat-des-lieux-de-la-consommation-en-france. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ANSM . 2017. Signalement par les entreprises d’une prescription ou utilisation non conforme de médicament. https://archiveansm.integra.fr/var/ansm_site/storage/original/application/d36d6dd7055c0ac1281bd1f75a62184c.pdf. [Accessed 21 December 2021 (5 pp.)] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niburski K., Niburski O. Impact of Trump's promotion of unproven COVID-19 treatments and subsequent internet trends: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e20044. doi: 10.2196/20044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez J., Roustit M., Lepelley M., Revol B., Cracowski J.L., Khouri C. Reported adverse drug reactions associated with the use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:878–880. doi: 10.7326/M20-7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Axfors C., Schmitt A.M., Janiaud P., Van’t Hooft J., Abd-Elsalam S., Abdo E.F., et al. Mortality outcomes with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19 from an international collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2349. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22446-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordet R. Is the drug a scientific, social or political object? Therapie. 2020;75:389–391. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kierzek G., Léo M. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé; 2018. Rapport sur l’amélioration de l’information des usagers et des professionnels de santé sur le médicament. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/ministere/documentation-et-publications-officielles/rapports/sante/article/rapport-sur-l-amelioration-de-l-information-des-usagers-et-des-professionnels. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Légifrance . 2013. Article R5121-152 – Code de la santé publique. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000028083982/. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ANSM . 2018. Bonnes pratiques de pharmacovigilance. https://ansm.sante.fr/documents/reference/bonnes-pratiques-de-pharmacovigilance. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Medicines Agency . 2018. Good pharmacovigilance practices. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance/good-pharmacovigilance-practices. [Accessed 21 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupui M., Micallef J., Lapeyre-Mestre M. Interest of large electronic health care databases in addictovigilance: lessons from 15 years of pharmacoepidemiological contribution. Therapie. 2019;74:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2018.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soeiro T., Lacroix C., Pradel V., Lapeyre-Mestre M., Micallef J. Early detection of prescription drug abuse using doctor shopping monitoring from claims databases: illustration from the experience of the French Addictovigilance Network. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:640120. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.640120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gérardin M., Rousselet M., Caillet P., Grall-Bronnec M., Loué P., Jolliet P., et al. French national health insurance database analysis and field study focusing on the impact of secure prescription pads on zolpidem consumption and sedative drug misuse: ZORRO study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027443. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vignot S., Daynes P., Bacon T., Vial T., Montagne O., Albin N., et al. Collaboration between health-care professionals, patients, and national competent authorities is crucial for prevention of health risks linked to the inappropriate use of drugs: a position paper of the ANSM (Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé) Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:635841. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.635841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]