Abstract

Background

Longitudinal observational cohort studies in cancer patients are important to move research and clinical practice forward. Continued study participation (study retention) is of importance to maintain the statistical power of research and facilitate representativeness of study findings. This study aimed to investigate study retention and attrition (drop-out) and its associated sociodemographic and clinical factors among head and neck cancer (HNC) patients and informal caregivers included in the Netherlands Quality of Life and Biomedical Cohort Study (NET-QUBIC).

Methods

NET-QUBIC is a longitudinal cohort study among 739 HNC patients and 262 informal caregivers with collection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), fieldwork data (interview, objective tests and medical examination) and biobank materials. Study retention and attrition was described from baseline (before treatment) up to 2-years follow-up (after treatment). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with retention in NET-QUBIC components at baseline (PROMs, fieldwork and biobank samples) and retention in general (participation in at least one component) were investigated using Chi-square, Fisher exact or independent t-tests (p< 0.05).

Results

Study retention at 2-years follow-up was 80% among patients alive (66% among all patients) and 70% among caregivers of patients who were alive and participating (52% among all caregivers). Attrition was most often caused by mortality, and logistic, physical, or psychological-related reasons. Tumor stage I/II, better physical performance and better (lower) comorbidity score were associated with participation in the PROMs component among patients. No factors associated with participation in the fieldwork component (patients), overall sample collection (patients and caregivers) or PROMs component (caregivers) were identified. A better performance and comorbidity score (among patients) and higher age (among caregivers) were associated with study retention at 2-years follow-up.

Conclusions

Retention rates were high at two years follow-up (i.e. 80% among HNC patients alive and 70% among informal caregivers with an active patient). Nevertheless, some selection was shown in terms of tumor stage, physical performance, comorbidity and age, which might limit representativeness of NET-QUBIC data and samples. To facilitate representativeness of study findings future cohort studies might benefit from oversampling specific subgroups, such as patients with poor clinical outcomes or higher comorbidity and younger caregivers.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Cohort study, Representativeness, Attrition, Retention

Background

Longitudinal observational cohort studies in (cancer) patients are important to move research and clinical practice forward. However, study retention (continued study participation) can be compromised in such studies. Attrition (drop-out) limits the statistical power of research and, in case attrition is selective, may lead to biased results and hamper representativeness of study findings [1]. Especially in studies among cancer patients study attrition may occur due to factors such as mortality and long-term side-effects of treatment.

Previous longitudinal cohort studies provided insight into study retention and attrition among cancer patients [2–9]. Two small studies in which patients were asked to complete patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) showed retention rates of 15% among 47 adolescent and young cancer patients (1–1.5 year follow-up) and 96% among 121 breast cancer patients (1 year follow-up) [2, 3]. In addition, Ness et al. (2016) [9] presented results of the Head and Neck 5000 study and showed that among 5356 head and neck cancer (HNC) patients 75% completed PROMs, and of 90%, 85% and 42% respectively oral rinse samples, blood samples and paraffin embedded tumor blocks were collected at baseline. At 4- and 12-months follow-up 63 and 57% of the patients completed the PROMs. In addition, Perez-Cruz et al. (2018) [6] reported that 67% of 744 advanced cancer patients showed up for a follow-up research visit at 2–5 weeks follow-up. Leuteritz et al. (2018) [5] showed that 89% of 577 young adult cancer patients completed PROMs at 1 year follow-up. A study by Ramsey et al. [7] with yearly PROM collection among 2625 colorectal cancer patients showed a retention rate of 58% of those alive (56% of all patients) at 2-years follow-up and 51% (47% of all patients) at 4 years follow-up. A study by Spiers et al. (2018) [8] among 1227 prostate cancer patients who were invited to complete PROMs at 3–6 years follow-up showed that 69% of those alive (62% of all patients) participated. Finally, Fossa et al. (2020) [4] showed that among 1436 testicular cancer patients 64% of those alive (54% of all patients) completed all three PROMs assessments over a time period of 17 years. In these studies retention rates were higher among patients who were younger [4, 7, 8], who were higher-educated [7, 8], had a higher socio-economic status [4, 7, 8], and had better clinical [4, 6, 8] and patient-reported outcomes [6, 7]. Mixed results were reported regarding gender [5–7].

Except for the study of Perez-Cruz et al. (2018) [6] and Ness et al. (2016) [9], all previous studies focused on the collection of a limited set of PROMs every 1 to 6 years. No study investigated retention and attrition in a longitudinal observational cohort study comprising different types of data, such as collection of PROMs, conduction of fieldwork assessments and collection of biobank samples, with multiple measurements per year. Also, so far, only in one study retention rates among informal caregivers of cancer patients was investigated [10]. This study of Fernix et al. (2006) [10] showed that among 206 informal caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients (all types) 85% participated in a face to face interview at 13-months follow-up.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate study retention and attrition in a longitudinal cohort study with a comprehensive assessment protocol among HNC patients and their informal caregivers using data of the Netherlands Quality of Life and Biomedical Cohort Study (NET-QUBIC), and to explore sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with study retention. NET-QUBIC is a longitudinal observational cohort study among 739 HNC patients and 262 informal caregivers with collection of PROMs, fieldwork data (interview, objective tests and medical examination) and biobank materials from before start of treatment up to 2-years follow-up [11, 12]. In a previous study patients evaluated this comprehensive assessment protocol as feasible in terms of time investment and intimacy [11]. The overarching objective of NET-QUBIC is to optimize diagnosis, treatment and supportive care by advancing interdisciplinary research [11, 12]. So far, more than 20 derivate studies are ongoing or have been published that use NET-QUBIC data and samples [12–18]. Further insight in study retention and attrition will facilitate interpretation of findings derived from these studies. Also, this study contributes to designing future longitudinal cohort studies with comprehensive assessment protocols among cancer patients.

Methods

In this study data of the NET-QUBIC observational cohort study was used [12]. Recruitment of NET-QUBIC participants took place in 7 HNC centers throughout the Netherlands. In total, 739 newly diagnosed HNC patients and 262 caregivers were recruited (March 2014 to June 2018). Inclusion criteria were previously untreated patients with newly diagnosed HNC (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, unknown primary; all stages); age ≥ 18 years; treatment with curative intent; able to write, read, and speak Dutch. Patients were excluded in case they were diagnosed with lymphoma, skin malignancies or thyroid cancer; were unable to understand the questions or test instructions; did not provide informed consent or had severe psychiatric co-morbidities (schizophrenia, Korsakoff’s syndrome, severe dementia). A partner, family member or close friend of the patient was asked to participate as informal caregiver. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at VUmc (2013.301(A2018.307)-NL45051.029.13) and at all local participating centers. The biobank protocol was also approved by the biobank committee of VUmc (2018.406). All patients and caregivers signed informed consent.

NET-QUBIC assessment protocol

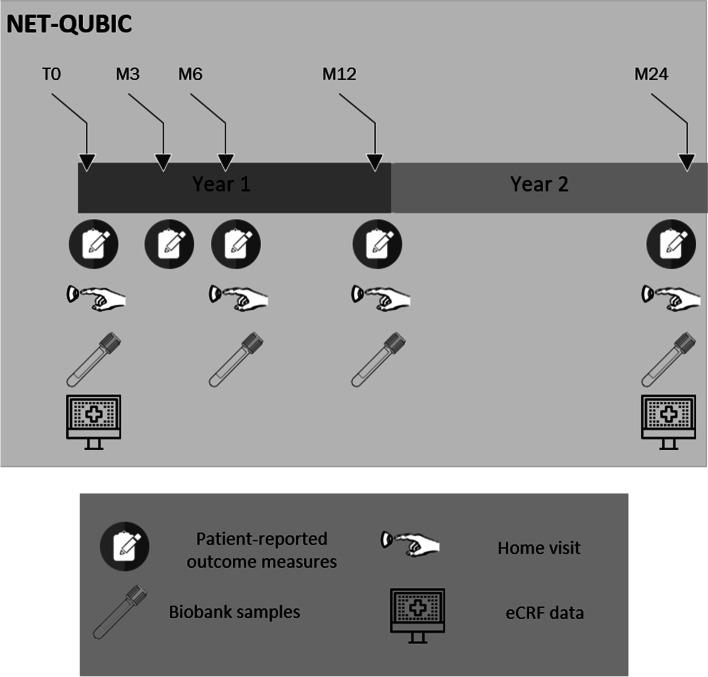

In the NET-QUBIC study a wide range of measures were collected, including clinical data, PROMs, fieldwork assessments and collection of biobank samples (see Fig. 1). Clinical data was collected after the end of primary treatment, and at 2-years follow-up. PROMs were completed at baseline (approximately 2 weeks after diagnosis), and at 3 months, 6 months, 1,2, 3, 4 and 5-years after treatment by both HNC survivors and their caregivers. Fieldwork assessments including interview data, objective tests, and medical examinations were performed at baseline, 6 months, and 1–2- and 5-years follow-up among HNC survivors only. In addition, tumour biopsies were collected at baseline and biobank samples (blood, oral rinse and saliva) at baseline, 6 months, and 1-, 2- and 5-years follow-up in patients. In caregivers blood and oral rinse were collected once at baseline. These samples were collected to be used as control samples for HNC patients, as informal caregivers are likely to be comparable to HNC patients in terms of lifestyle characteristics such as alcohol consumption and smoking behaviour. For detailed insight on collected PROMs, fieldwork assessments and biobank samples we refer to previous publications [11, 12] and the NET-QUBIC website (www.kubusproject.nl). Data collection from 3- to 5-years follow-up is currently ongoing. This study, therefore, focuses on study retention and attrition up to 2 years follow-up (last 2-year follow-up assessment: August 2020).

Fig. 1.

NET-QUBIC assessment protocol

Study follow-up procedures

All patients and informal caregivers were asked to participate in the follow-up assessments. To limit study attrition due to loss to follow-up primary contact information was collected (name, address, phone number (home and mobile) and email address of patients and their informal caregivers. Patients and informal caregivers were asked to complete the follow-up PROMs using paper and pencil at home. Patients and informal caregivers received the PROMs by regular post and were reminded twice to complete the PROMs (also by regular post). The fieldwork assessments were scheduled by phone. In case a patient could not be reached we phoned again at a later time point. When the patient could still not be reached after several phone calls an e-mail was send to the patient (if an email address was available). To facilitate study retention the fieldwork assessments were performed at the patients’ home (with the possibility of a fieldwork assessment at the hospital when preferred by the patient). Oral rinse and blood samples were collected at time of the fieldwork assessment (preferred) or at time of clinical follow-up visit (if not willing to participate in the fieldwork assessment). Yearly newsletters were sent to patients and informal caregivers. Also, patients and their general practitioners were informed by regular post on part of the results of their fieldwork assessment and blood values (e.g. blood pressure, body mass index or haemoglobin concentration). Patients and informal caregivers were allowed to participate in a subset of NET-QUBIC components (e.g., PROMs and biobank component only) to minimize study attrition. In case patients or informal caregivers dropped-out the reason was reported.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY USA). Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the NET-QUBIC study population were described using descriptive statistics.

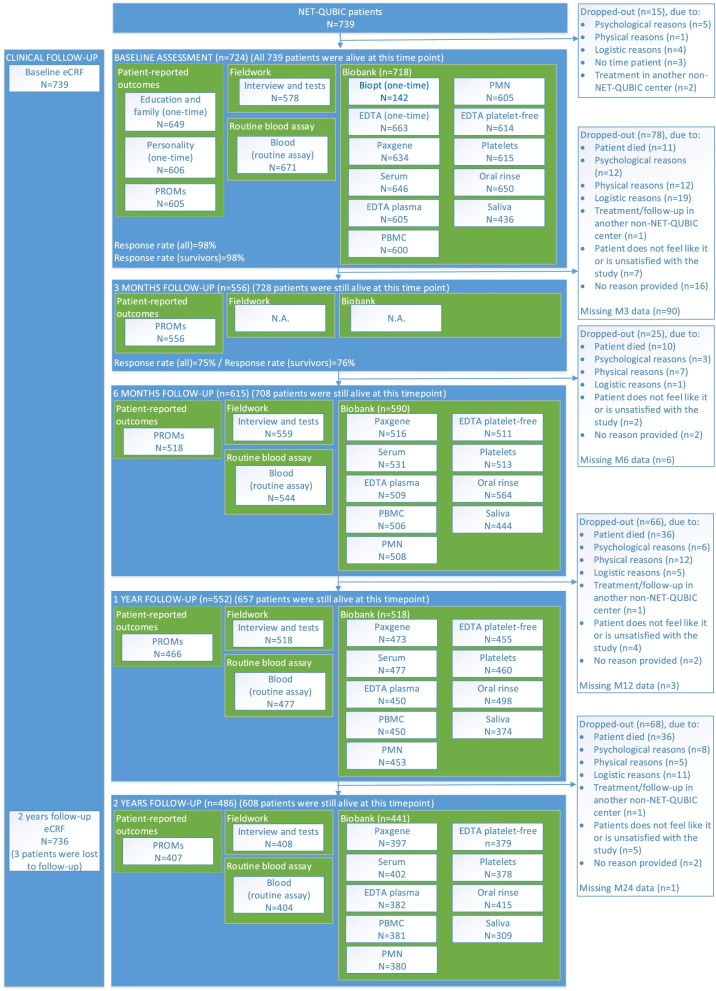

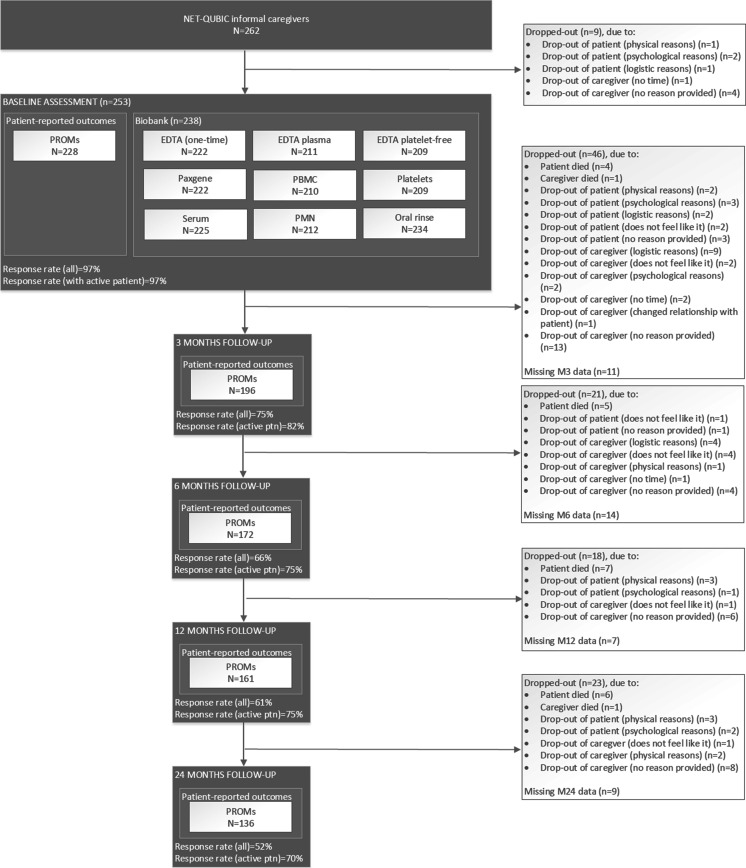

To describe study retention and attrition up to 2-years follow-up a detailed flow diagram is provided (Figs. 2 and 3). Patients/caregivers were coded as ‘study retention in general (yes)’ at a particular time point in case data was available on at least one NET-QUBIC component (PROMs, fieldwork, biobank). Patients/caregivers were coded as ‘study attrition (yes)’ in case no data was available on all components (PROMs, fieldwork, biobank) at this time point and all further time points. Patients/caregivers were coded as ‘drop-out: patient/caregiver died’ in case they died while still participating in the study. Other categories for drop-out were psychological reasons (e.g. distress, fatigue), physical reasons (e.g. too ill, palliative treatment), logistic reasons (e.g. patient can repeatedly not be reached), no time from the patient’s point of view, treatment or follow-up in another non-NET-QUBIC medical center or not wanting to participate anymore. The total number of patients/caregivers who died is, however, higher as some patients/caregivers dropped out due to other reasons before they died. Mortality in patients is presented separately as the number of patients alive per time point. In the group of caregivers we had no information on mortality after they dropped out. In case the patient died or dropped out, the caregiver automatically also dropped out.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of NET-QUBIC patients

Fig. 3.

Flow diagram of NET-QUBIC informal caregivers

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with retention in various assessment components at baseline and retention in general (participation in at least one component) at 6 months, 1- and 2-years follow-up were investigated using Chi-square tests, Fisher exact tests or independent t-tests. Factors associated with study retention at baseline were investigated for the main components (PROMs, fieldwork and biobank assessment) as well as the biobank subcomponents: tumour biopsy, blood, oral rinse and saliva. These subcomponents were studied separately as due to the study design and logistic reasons different sociodemographic and clinical factors may have influenced availability of samples. Study retention in general was investigated twice per time point: i) among all patients/caregivers and ii) among patients alive (to preclude factors associated with survival) or among caregivers of patients who were still alive and participating (to preclude factors associated with drop-out of patients). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Previously it was shown that among 1861 patients invited for NET-QUBIC 739 patients participated (40%) [12]. In addition, 262 informal caregivers participated. Table 1 provides insight into the baseline characteristics of all patients and informal caregivers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HNC patients and their informal caregivers

| HNC patients (n = 739) |

Informal caregivers (n = 262) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 63.2 ± 9.7 | 58.8 ± 11.6 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Men | 549 (74%) | 70 (27%) |

| Women | 190 (26%) | 192 (73%) |

| Education level, n (%)a | ||

| Low | 279 (43%) | 82 (37%) |

| Middle | 171 (26%) | 63 (28%) |

| High | 198 (31%) | 78 (35%) |

| Living situation, n (%)b | ||

| Living alone | 163 (25%) | 8 (4%) |

| Living with partner (with or without children) | 451 (69%) | 205 (91%) |

| Other (e.g. living with children, living with parents or assisted living | 35 (5%) | 12 (5%) |

| Tumor location, n (%) | ||

| Oral Cavity | 199 (27%) | |

| Oropharynx | 262 (36%) | |

| Hypopharynx | 52 (7%) | |

| Larynx | 205 (28%) | |

| Unknown primary | 21 (3%) | |

| Clinical disease Stage, n (%) | ||

| Stage 0/Ic | 163 (22%) | |

| Stage II | 132 (18%) | |

| Stage III | 127 (17%) | |

| Stage IV | 317 (43%) | |

| Type of treatment, n (%)d | ||

| Single treatment | ||

| Surgery | 152 (21%) | |

| Radiotherapy | 241 (33%) | |

| Combination treatment | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 215 (29%) | |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 106 (14%) | |

| Surgery and chemoradiotherapy | 23 (3%) | |

| Othere | 1 (0.1%) | |

| WHO performance, n (%) | ||

| Able to carry out normal activity | 507 (69%) | |

| Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out light work | 191 (26%) | |

| Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work | 40 (5%) | |

| Capable of only limited self-care | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Completely disabled | 0 (0%) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%)f | ||

| None | 204 (29%) | |

| Mild | 264 (38%) | |

| Moderate | 155 (22%) | |

| Severe | 76 (11%) | |

| HPV-status (oropharynx cancer only), n (%)g | ||

| Positive | 99 (43%) | |

| Negative | 130 (57%) | |

| Baseline smoking status, n (%)h | ||

| Daily smoker | 127 (22%) | 38 (17%) |

| Not a daily smoker | 445 (78%) | 187 (83%) |

| Baseline alcohol consumption, n (%)i | ||

| Excessive alcohol consumption | 129 (22%) | 25 (11%) |

| No excessive alcohol consumption | 445 (78%) | 200 (89%) |

| Relation informal caregiver – patient, n (%)j | ||

| Partner | 219 (84%) | |

| Daughter/son | 31 (12%) | |

| Other (i.e. sibling, friend, ex-partner) | 10 (4%) | |

aMissing in 91 patient and 39 informal caregivers. bMissing in 90 patients and 37 informal caregivers. cOne patient had a cTNM stage of 0, however, pTNM was stage 2. dOne patient died before start of treatment. eRadiotherapy with hyperthermic treatment. fMissing in 40 patients. gMissing in 33 oropharynx cancer patients. hMissing in 167 patients and 37 informal caregivers. iDefined as > 14 units of alcohol per week for women and > 21 units per week for men. Missing in 165 patients and 37 informal caregivers. jMissing in 2 informal caregivers

Study retention and attrition

As presented in Fig. 2, baseline clinical data was available of all 739 patients. Of the total 739 patients, 724 patients (98%) had available baseline data for PROMs, fieldwork and/or biobank samples. Fifteen patients dropped out prior to the baseline assessment due to psychological reasons (n = 5), logistic reasons (e.g., quick start treatment) (n = 4), no time from the patients point of view (n = 3), treatment in another non-NET-QUBIC center (n = 2) or physical reasons (n = 1). Study retention in general among all 739 patients at 3- and 6-months and 1- and 2-years follow-up was 556 (75%), 615 (83%), 552 (75%) and 486 patients (66%), respectively. Up to 2-years follow-up 131 patients died (110 patients with cancer and 21 patients with another cause). When only patients alive were taken into account study retention was 80% at 2-years follow-up (486 of 608 patients alive). At 3- and 6-months and 1- and 2-years follow-up respectively 11% (78 of 739 patients), 3% (25 of 739 patients), 9% (66 of 739 patients) and 9% (68 of 739 patients) of all patients dropped out, equaling to a total study attrition (including drop-out prior to baseline assessment) of 34% (252 of 739 patients). Most important reasons for study attrition were mortality (n = 93/252 (37%)), logistic reasons (n = 40/252 (16%)), physical reasons (n = 37/252 (15%)), and psychological reasons (n = 34/252 (13%)).

Among informal caregivers of HNC patients, of the 262 informal caregivers that signed informed consent, 253 informal caregivers completed the PROMs and/or biobank assessment at baseline (97%) (Fig. 3). Of the nine informal caregivers who did not complete the PROMs and/or biobank, reasons for non-completion were drop-out of the patient they cared for (n = 4) and drop-out of the informal caregiver (n = 5). Study retention in general among all 262 informal caregivers at 3- and 6-months and 1 and 2-years follow-up was 196 (75%), 172 (66%), 161 (61%) and 136 informal caregivers (52%) Respectively. At 3- and 6-months and 1- and 2-years follow-up, respectively 18% (46 of 262 informal caregivers), 8% (21 of 262 informal caregivers), 7% (18 of 262 informal caregivers) and 9% (23 of 262 informal caregivers) informal caregivers dropped out, equaling to a total study attrition (including drop-out prior to baseline assessment) of 45% (117 of 262 informal caregivers). Drop-out was initiated by the informal caregiver (n = 68/117, 58%) or followed drop-out of the patients (n = 49/117, 42%), of which 19% (22/117) because the patient died. When only informal caregivers were taken into account of whom the patient they cared for was still alive and participating in the study, study retention was 70% at 2-years follow-up (136 of 193 informal caregivers with an active patient).

Factors associated with study retention

At baseline, 605 patients completed the PROMs, 578 patients the fieldwork assessment and 718 patients the biobank assessment (Fig. 2). Patients who had a less advanced tumor stage, better physical performance and lower ACE-27 comorbidity score were more likely to complete the PROMs at baseline (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences between patients who participated in the fieldwork assessment or biobank assessment protocol (overall), and those who did not. However, some differences on subcomponents of the biobank assessment were, found. Patients with a tumor biopsy were less often diagnosed with laryngeal cancer, had a more advanced tumor stage, had a worse physical performance and had a higher comorbidity score. Blood samples were more often collected among patients who received single treatment and saliva was more often available of patients who were older and had a better physical performance score. Among informal caregivers there were no statistically significant differences between those who did and those who did not participate in the PROMs or biobank assessment at baseline (Table 3).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients that participated in the various components (PROMs, interview, biobank) and subcomponents (accelerometer, tumour biopsy, blood, oral rinse and saliva) of NET-QUBIC at baseline

|

PROMsa Yes N = 605 |

PROMsa No N = 134 |

P-value |

Fieldwork Yes N = 578 |

Fieldwork No N = 161 |

P-value |

Biobank Yes N = 718 |

Biobank No N = 21 |

P-value | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Men | 450 (74%) | 99 (74%) | 0.90 | 438 (76%) | 111 (69%) | 0.08 | 536 (75%) | 13 (62%) | 0.19 | |||

| Women | 155 (26%) | 35 (26%) | 140 (24%) | 50 (31%) | 182 (25%) | 8 (38%) | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 63.5 ± 9.5 | 62.0 ± 10.9 | 0.14 | 63.6 ± 9.3 | 61.9 ± 11.0 | 0.06 | 63 ± 9.7 | 62 ± 11.3 | 0.57 | |||

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.47c | |||||||||

| Oral Cavity | 168 (28%) | 31 (23%) | 147 (25%) | 52 (32%) | 191 (27%) | 8 (38%) | ||||||

| Oropharynx | 211 (35%) | 51 (38%) | 212 (37%) | 50 (31%) | 256 (36%) | 6 (29%) | ||||||

| Hypopharynx | 38 (6%) | 14 (10%) | 38 (7%) | 14 (9%) | 52 (7%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| Larynx | 169 (28%) | 36 27%) | 164 (28%) | 41 (25%) | 199 (28%) | 6 (29%) | ||||||

| Unknown primary | 19 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 17 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 20 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||||||

| Clinical disease Stage, n (%) | 0.011 | 0.16 | 0.87c | |||||||||

| 0/I | 147 (24%) | 16 (12%) | 133 (23%) | 30 (19%) | 159 (22%) | 4 (19%) | ||||||

| II | 108 (18%) | 24 (18%) | 94 (16%) | 38 (24%) | 129 (18%) | 3 (14%) | ||||||

| III | 97 (16%) | 30 (22%) | 99 (17%) | 28 (17%) | 122 (17%) | 5 (24%) | ||||||

| IV | 253 (42%) | 64 (48%) | 252 (44%) | 65 (40%) | 308 (43%) | 9 (43%) | ||||||

| Treatment, n (%)b | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.16 | |||||||||

| Single treatment | 326 (54%) | 67 (50%) | 306 (53%) | 87 (54%) | 385 (54%) | 8 (38%) | ||||||

| Combination treatment | 279 (46%) | 66 (50%) | 272 (47%) | 73 (46%) | 332 (46%) | 13 (62%) | ||||||

| WHO performance, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.72 | |||||||||

| Able to carry out normal activity | 426 (70%) | 81 (60%) | 394 (68%) | 113 (70%) | 493 (69%) | 14 (67%) | ||||||

| Restricted in physically strenuous activity | 154 (25%) | 37 (28%) | 154 (27%) | 37 (23%) | 186 (26%) | 5 (24%) | ||||||

| Ambulatory | 25 (4%) | 16 (12%) | 30 (5%) | 11 (5%) | 39 (5%) | 2 (10%) | ||||||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.003 | 0.63 | 0.30 | |||||||||

| None | 180 (31%) | 24 (20%) | 164 (30%) | 40 (27%) | 200 (29%) | 4 (24%) | ||||||

| Mild | 223 (39%) | 41 (34%) | 206 (37%) | 58 (39%) | 257 (38%) | 7 (41%) | ||||||

| Moderate | 117 (20%) | 38 (31%) | 118 (21%) | 37 (25%) | 153 (22%) | 2 (12%) | ||||||

| Severe | 57 (10%) | 19 (16%) | 62 (11%) | 14 (9%) | 72 (11%) | 4 (24%) | ||||||

|

Tumor biopsy Yes N = 142 |

Tumor biopsy No N = 597 |

P-value |

Bloodd Yes N = 655 |

Bloodd No N = 84 |

P-value |

Oral rinse Yes N = 650 |

Oral rinse No N = 89 |

P-value |

Saliva Yes N = 436 |

Saliva No N = 303 |

P-value | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Men | 99 (70%) | 450 (75%) | 489 (75%) | 60 (71%) | 487 (75%) | 62 (70%) | 331 (76%) | 218 (72%) | ||||

| Women | 43 (30%) | 147 (25%) | 166 (25%) | 24 (29%) | 163 (25%) | 27 (30%) | 105 (24%) | 85 (28%) | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 62.5 ± 10.0 | 63.4 ± 9.8 | 0.29 | 63.4 ± 9.6 | 62.3 ± 10.5 | 0.36 | 63.3 ± 9.6 | 62.9 ± 11.1 | 0.73 | 64.0 ± 8.9 | 62.2 ± 10.8 | 0.022 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.022 | 0.58 | 0.20 | 0.26 | ||||||||

| Oral Cavity | 41 (29%) | 158 (26%) | 173 (26%) | 26 (31%) | 168 (26%) | 31 (35%) | 105 (24%) | 94 (31%) | ||||

| Oropharynx | 56 (39%) | 206 (34%) | 232 (35%) | 30 (36%) | 229 (35%) | 33 (37%) | 166 (38%) | 96 (32%) | ||||

| Hypopharynx | 16 (11%) | 36 (6%) | 47 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 49 (8%) | 3 (3%) | 31 (7%) | 21 (7%) | ||||

| Larynx | 26 (18%) | 179 (30%) | 186 (28%) | 19 (23%) | 186 (29%) | 19 (21%) | 122 (28%) | 83 (27%) | ||||

| Unknown primary | 3 (2%) | 18 (3%) | 17 (3%) | 4 (5%) | 18 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 12 (3%) | 9 (3%) | ||||

| Clinical disease Stage, n (%) | 0.020 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| 0/I | 18 (13%) | 145 (24%) | 146 (22%) | 17 (20%) | 142 (22%) | 21 (24%) | 101 (23%) | 62 (20%) | ||||

| II | 28 (20%) | 104 (17%) | 118 (18%) | 14 (17%) | 121 (19%) | 11 (12%) | 70 (16%) | 62 (20%) | ||||

| III | 24 (17%) | 103 (17%) | 109 (17%) | 18 (21%) | 104 (16%) | 23 (26%) | 72 (17%) | 55 (18%) | ||||

| IV | 72 (51%) | 245 (41%) | 282 (43%) | 35 (42%) | 283 (44%) | 34 (38%) | 193 (44%) | 124 (41%) | ||||

| Treatment, n (%)b | 0.39 | 0.043 | 0.15 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Single treatment | 71 (50%) | 322 (54%) | 357 (55%) | 36 (43%) | 352 (54%) | 41 (46%) | 231 (53%) | 162 (54%) | ||||

| Combination treatment | 71 (50%) | 274 (46%) | 297 (45%) | 48 (57%) | 297 (46%) | 48 (54%) | 205 (47%) | 140 (46%) | ||||

| WHO performance, n (%) | 0.028 | 0.13 | 0.97 | 0.046 | ||||||||

| Able to carry out normal activity | 86 (61%) | 421 (71%) | 456 (70%) | 51 (61%) | 445 (68%) | 62 (70%) | 309 (71%) | 198 (65%) | ||||

| Restricted in physically strenuous activity | 43 (30%) | 148 (25%) | 166 (25%) | 25 (30%) | 169 (26%) | 22 (25%) | 110 (25%) | 81 (27%) | ||||

| Ambulatory | 13 (9%) | 28 (5%) | 33 (5%) | 8 (10%) | 36 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 17 (4%) | 24 (8%) | ||||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.030 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.45 | ||||||||

| None | 30 (21%) | 174 (31%) | 180 (29%) | 24 (31%) | 178 (29%) | 26 (32%) | 129 (31%) | 75 (27%) | ||||

| Mild | 50 (36%) | 214 (38%) | 234 (38%) | 30 (38%) | 236 (38%) | 28 (35%) | 159 (38%) | 105 (38%) | ||||

| Moderate | 41 (29%) | 114 (20%) | 139 (22%) | 16 (21%) | 137 (22%) | 18 (22%) | 85 (20%) | 70 (25%) | ||||

| Severe | 19 (14%) | 57 (10%) | 68 (11%) | 8 (10%) | 67 (11%) | 9 (11%) | 46 (11%) | 30 (11%) | ||||

Patients with PROMs data, interview data or biobank samples may have missing data on components of the assessment. Groups were compared using chi square tests, unless otherwise specified. Significant p-values (p < 0.05) were printed in bold. Abbreviations: PROMs, patient-reported outcome measure, SD, standard deviation, WHO, World Health Organization

aThe collected PROMs on education, family or personality were not taken into account, as patients were asked to complete these PROMs as part of the follow-up assessment in case data was missing

bOne patient died before start of treatment and was therefore not included in the analysis on treatment

cCompared using Fisher Exact Test

dIncluding paxgene, serum, EDTA plasma, PBMC, PMN, EDTA platelet-free and/or platelets

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of informal caregivers that participated in the various components (PROMs, biobank) of NET-QUBIC at baseline

| PROMs Yes N = 228 |

PROMs No N = 34 |

P-value | Biobank Yes N = 238 |

Biobank No N = 24 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 62 (27%) | 8 (24%) | 0.65 | 61 (26%) | 9 (38%) | 0.21 |

| Women | 166 (73%) | 26 (76%) | 177 (74%) | 15 (63%) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 59.3 ± 11.3 | 55.7 ± 13.3 | 0.09 | 58.9 ± 11.7 | 57.7 ± 10.1 | 0.63 |

| Relation informal caregiver – patienta, n (%) | 0.14b | 0.61b | ||||

| Partner | 194 (85%) | 25 (76%) | 200 (84%) | 19 (83%) | ||

| Daughter/son | 26 (11%) | 5 (15%) | 27 (11%) | 4 (17%) | ||

| Other (i.e. sibling, friend, ex-partner) | 7 (3%) | 3 (9%) | 10 (4%) | 0 (0%) | ||

Informal caregivers with PROMs data or biobank samples may have missing data on specific components of the assessment. Results on the representativeness of data for a specific research question may thus differ from above results. Groups were compared using chi square tests, unless otherwise specified. Significant p-values (p < 0.05) were printed in bold

aMissing in two informal caregivers

bCompared using Fisher Exact Test

Abbreviations: PROMs patient-reported outcome measure, SD standard deviation

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with study retention in general among patients at 6-months and 1- and 2-years follow-up are presented in Table 4. Among all HNC patients, a less advanced tumor stage and a better physical performance score were associated with study retention at all time points. In addition, a better ACE-27 comorbidity score was associated with study retention at 1- and 2-years follow-up, and larynx cancer was associated with study retention at 2-years follow-up. Among HNC patients alive, better physical performance remained associated with study retention at 6-months and 1- and 2-years follow-up and ACE-27 comorbidity score with study retention at 2-years follow-up.

Table 4.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of active patients and drop-outs at 6-months, and 1- and 2-years follow-up

| 6 months follow-up | 1 year follow-up | 2 years follow-up | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active patients N = 615 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 124 |

Drop-outs (excl. deceased) N = 93 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (deceased) |

Active patients N = 552 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 187 |

Drop-outs (excl. deceased) N = 105 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (deceased) |

Active patients N = 486 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 253 |

Drop-outs (excl. deceased) N = 122 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (deceased) |

|

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Men | 454 (74%) | 95 (77%) | 72 (77%) | 0.52 | 0.46 | 409 (74%) | 140 (75%) | 78 (74%) | 0.84 | 0.97 | 358 (74%) | 191 (75%) | 86 (70%) | 0.59 | 0.48 |

| Women | 161 (26%) | 29 (23%) | 21 (23%) | 143 (26%) | 47 (25%) | 27 (26%) | 128 (26%) | 62 (25%) | 36 (30%) | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 63.4 ± 9.6 | 62.6 ± 10.6 | 61.6 ± 10.9 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 63.3 ± 9.6 | 63.1 ± 10.3 | 62.3 ± 10.6 | 0.84 | 0.36 | 63.5 ± 9.7 | 62.8 ± 9.8 | 62.1 ± 10.3 | 0.35 | 0.17 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.011 | 0.65 | |||||||||

| Oral Cavity | 165 (27%) | 34 (17%) | 23 (25%) | 146 (26%) | 53 (28%) | 24 (23%) | 126 (26%) | 73 (29%) | 35 (29%) | ||||||

| Oropharynx | 219 (36%) | 43 (35%) | 32 (34%) | 197 (36%) | 65 (35%) | 36 (34%) | 174 (36%) | 88 (35%) | 39 (32%) | ||||||

| Hypopharynx | 41 (7%) | 11 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 34 (6%) | 18 (10%) | 9 (9%) | 24 (5%) | 28 (11%) | 9 (7%) | ||||||

| Larynx | 171 (28%) | 34 (27%) | 29 (31%) | 158 (29%) | 47 (25%) | 35 (33%) | 147 (30%) | 58 (23%) | 37 (30%) | ||||||

| Unknown primary | 19 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 17 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 15 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 2 (2%) | ||||||

| Clinical disease Stage, n (%) | 0.011 | 0.11 | < 0.001 | 0.12 | < 0.001 | 0.50 | |||||||||

| 0/I | 148 (24%) | 15 (12%) | 14 (15%) | 139 (25%) | 24 (13%) | 20 (19%) | 126 (26%) | 37 (15%) | 28 (23%) | ||||||

| II | 113 (18%) | 19 (15%) | 15 (16%) | 106 (19%) | 26 (14%) | 17 (16%) | 94 (19%) | 38 (15%) | 22 (18%) | ||||||

| III | 100 (16%) | 27 (22%) | 22 (24%) | 88 (16%) | 39 (21%) | 26 (25%) | 76 (16%) | 51 (20%) | 26 (21%) | ||||||

| IV | 254 (41%) | 63 (51%) | 42 (45%) | 219 (40%) | 98 (52%) | 42 (40%) | 190 (39%) | 127 (50%) | 46 (38%) | ||||||

| Type of treatment, n (%)a | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.018 | 0.54 | |||||||||

| Single treatment | 333 (54%) | 60 (49%) | 48 (52%) | 305 (55%) | 88 (47%) | 57 (54%) | 274 (56%) | 119 (47%) | 65 (53%) | ||||||

| Combination treatment | 282 (46%) | 63 (51%) | 45 (48%) | 247 (45%) | 98 (53%) | 48 (46%) | 212 (44%) | 133 (53%) | 57 (47%) | ||||||

| WHO performance, n (%) | < 0.001 | 0.018 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | < 0.001 | 0.042 | |||||||||

| Able to carry out normal activity | 442 (72%) | 65 (52%) | 56 (60%) | 400 (72%) | 107 (57%) | 68 (65%) | 364 (75%) | 143 (57%) | 79 (65%) | ||||||

| Restricted in physically strenuous activity | 148 (24%) | 43 (35%) | 28 (30%) | 136 (25%) | 55 (29%) | 27 (26%) | 107 (22%) | 84 (33%) | 35 (29%) | ||||||

| Ambulatory | 25 (4%) | 16 (13%) | 9 (10%) | 16 (3%) | 25 (13%) | 10 (9%) | 15 (3%) | 26 (10%) | 8 (7%) | ||||||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.003 | 0.06 | < 0.001 | 0.016 | |||||||||

| None | 179 (30%) | 25 (22%) | 21 (25%) | 166 (32%) | 38 (22%) | 21 (22%) | 149 (32%) | 55 (23%) | 25 (22%) | ||||||

| Mild | 226 (39%) | 38 (34%) | 30 (36%) | 205 (39%) | 59 (34%) | 37 (38%) | 189 (41%) | 75 (32%) | 41 (37%) | ||||||

| Moderate | 123 (21%) | 32 (29%) | 25 (30%) | 105 (20%) | 50 (29%) | 30 (31%) | 86 (19%) | 69 (29%) | 35 (31%) | ||||||

| Severe | 59 (10%) | 17 (15%) | 8 (10%) | 49 (9%) | 27 (16%) | 9 (9%) | 39 (8%) | 37 (16%) | 11 (10%) | ||||||

Active patients may have missing data on specific components of the assessment. Groups were compared using chi square tests. Significant p-values (p < 0.05) were printed in bold

aOne patient died before start of treatment and was therefore not included in the analysis on treatment

Abbreviations: SD standard deviation, WHO World Health Organization

Among all informal caregivers, higher age was associated with study retention at 1- and 2-years follow-up. This association remained statistically significant among informal caregivers of patients who were still alive and participating (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of active informal caregivers and drop-outs at 6-months, and 1- and 2-years follow-up

| 6 months follow-up | 1 year follow-up | 2 years follow-up | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active caregivers N = 172 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 90 |

Drop-outs (excl. With inactive patients) N = 58 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (excl. inactive) |

Active caregivers N = 161 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 101 |

Drop-outs (excl. With inactive patients) N = 54 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (excl. inactive) |

Active caregivers N = 136 |

Drop-outs (all) N = 126 |

Drop-outs (excl. With inactive patients) N = 57 |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (all) |

p-value active vs. drop-outs (excl. inactive) |

|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.77 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.75 | |||||||||

| Men | 47 (27%) | 23 (26%) | 12 (21%) | 42 (26%) | 28 (28%) | 11 (20%) | 34 (25%) | 36 (29%) | 13 (23%) | ||||||

| Women | 125 (73%) | 67 (74%) | 46 (79%) | 119 (74%) | 73 (72%) | 43 (80%) | 102 (75%) | 90 (71%) | 44 (77%) | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 59.7 ± 10.9 | 57.1 ± 12.7 | 57.2 ± 11.6 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 60.0 ± 10.4 | 56.9 ± 13.0 | 56.2 ± 12.6 | 0.042 | 0.030 | 60.9 ± 9.9 | 56.5 ± 12.8 | 55.0 ± 12.2 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Relation informal caregiver – patienta, n (%) | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.26 | |||||||||

| Partner | 151 (89%) | 68 (77%) | 48 (83%) | 140 (87%) | 79 (80%) | 46 (85%) | 121 (89%) | 98 (79%) | 46 (81%) | ||||||

| Daughter/son | 16 (9%) | 15 (17%) | 7 (12%) | 15 (9%) | 16 (16%) | 6 (11%) | 11 (8%) | 20 (16%) | 7 (12%) | ||||||

| Other (i.e. sibling, ex-partner)friend, | 5 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 3 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 6 (5%) | 4 (7%) | ||||||

Informal caregivers with PROMs data or biobank samples may have missing data on specific components of the assessment. Results on the representativeness of data for a specific research question may thus differ from above results. Groups were compared using chi square tests, unless otherwise specified. Significant p-values (p < 0.05) were printed in bold

aMissing in two informal caregivers

Abbreviations: PROMs patient-reported outcome measure, SD standard deviation

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate study retention and attrition, and sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with study retention up to two years follow-up in a longitudinal cohort study among HNC patients and their informal caregivers. At 2-years follow-up, study retention was 80% among patients alive at that time-point (66% among all included HNC patients) and 70% among informal caregivers with a patient still actively participating in the study (52% among all included informal caregivers). Reasons for study attrition among HNC patients were mostly mortality-related, followed by logistic, physical, or psychological factors. Both sociodemographic and clinical outcomes influenced participation in the different NET-QUBIC (sub) components (PROMs, tumour biopsy, blood, and saliva) at baseline. Study retention in general (participation in at least one NET-QUBIC component) at 2-years follow-up was associated with a better physical performance and lower comorbidity score (patients still alive) and younger age (caregivers).

The NET-QUBIC retention rate of 66–80% among HNC patients is relatively high compared to the retention rate over time of 56% (among all patients included at baseline) to 58% (among all patients included at baseline and believed to be alive) at 2-years follow-up found in a previous observational cohort study among colorectal cancer patients (recalculated) [7]. It is also high in comparison to another large observational cohort study (i.e. Head and Neck 5000) which showed that 57% of HNC patients completed PROMs at 1-years follow-up [9]. A possible explanation might be that, by study design, we facilitated study retention by performing the fieldwork assessment at the patients’ home (and the possibility of a fieldwork assessment at the hospital when preferred by the patient), by sending reminders by post in collecting PROMs data, and by sending yearly newsletters to patients and informal caregivers. A previous meta-analysis on the effectiveness of retention strategies in both clinical and non-clinical observational cohort studies also showed that offering site and home visits might improve study retention. However, no effects of newsletters and reminders were found [1]. The high retention rate in the NET-QUBIC study might also result from the design of the NET-QUBIC study, in which patients were allowed to participate in a subset of NET-QUBIC components (e.g., fieldwork and biobank component only) to minimize study attrition. When we focus on the collection of PROMs, 67% of patients alive participated at 2-years follow-up, whereas 67% of patients alive participated in the fieldwork component and 73% in the biobank component. These high percentages per NET-QUBIC component support the previous findings of van Nieuwenhuizen et al. [11], who showed that a comprehensive assessment protocol as used in the NET-QUBIC study is evaluated as feasible by patients in terms of time investment and intimacy. The NET-QUBIC retention rate of 61 and 52% (all informal caregivers) to 75 and 70% (all informal caregivers with a patient still actively participating in the study) at respectively 1 and 2-years follow-up is lower than the retention rate of 85% at 13-months follow-up reported in a study in which face to face interviews were conducted among informal caregivers of terminally ill patients [10]. An explanation for this difference might be that informal caregivers are more likely to participate in face to face interviews in comparison to completing PROMs (in NET-QUBIC informal caregivers only filled in PROMs at the follow-up time points), but more research is needed on this hypothesis.

The most important reason for study attrition among HNC patients in the NET-QUBIC study was mortality, followed by logistic, physical or psychological reasons, which are also common reasons for study attrition in clinical trials among cancer patients [19, 20]. In contrast to previous findings [4, 7, 8], age was not associated with study retention in general. In line with previous studies [4, 6, 8], however, better clinical outcomes such as a better physical performance and favourable comorbidity score were found to be associated with study retention. Together with previous results of Verdonck-de Leeuw et al. (2019) [12] who showed that HNC patients who participated in the NET-QUBIC study were younger, more often male, diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer, and treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy (compared to all HNC patients diagnosed), these findings indicate that NET-QUBIC data and samples might be slightly selective. Also, data and samples of informal caregivers of HNC patients are not entirely representative, as older caregivers were more likely to continue study participation. Future NET-QUBIC researchers should be aware of these differences in participation and retention when writing the data analysis plan of their NET-QUBIC study and reflect on the representativeness of their findings in the discussion section. In addition, future cohort studies might benefit from oversampling specific subgroups such as patients with poor clinical outcomes or younger caregivers.

Besides differences in study retention over time, some minor differences were found between patients who did and who did not participate in the different NET-QUBIC (sub) components at baseline. Patients with worse clinical outcomes (e.g., worse physical performance) were less likely to complete PROMs and to participate in saliva collection. These (sub) components needed to be performed by the patient without the researcher/fieldworker present, which might be more difficult for patients with a poorer physical performance (e.g., due to inability to open saliva tubes or to post the PROMs/saliva tubes). Tumor biopsies, however, were more often collected among patients with worse tumor-specific and clinical outcomes. This might be explained by the NET-QUBIC study design, in which additional tumor biopsies were only collected in case tumor biopsies were already collected for diagnostics purposes and sufficient tumor tissue was available. Finally, older age was associated with higher participation in the collection of saliva samples. Only patients who participated in the fieldwork component were asked to collect saliva samples the following day. The higher age among participants of the saliva component might, consequently, directly result from the higher age among participants of the fieldwork assessment (although non-significant, p-value of 0.06). Our hypothesis is that working-aged patients are less likely to participate in the fieldwork/saliva (sub) component due to work obligations. These differences among participants and non-participants might limit representativeness of NET-QUBIC data and samples. However, it might also improve representativeness of NET-QUBIC data. For example, the older age among patients who participated in the fieldwork or saliva (sub) component may counteract the lower recruitment rate among older HNC patients found by Verdonck-de Leeuw et al. [12].

To improve retention rates in future longitudinal cohort studies in cancer patients and their informal caregiver, we, suggest to personalize the method of participation and offer both online and paper and pencil options to complete the PROMs. In the NET-QUBIC study we asked all patients and informal caregivers to complete the PROMs using paper and pencil, as it was estimated that about 30% quite some HNC patients have no internet or limited computer skills has no access to the internet or limited computer skills [21, 22]. Some, potentially younger, HNC patients and informal caregivers may, however, be more likely to complete PROMs on a computer or smartphone. In addition, although we have no data to support this assumption, we assume that the involvement of a dedicated research nurse or research coordinator for a long period of time is of great importance for study retention.

A strength of this study is that it is the first study that investigated study retention and attrition in a longitudinal cohort study among cancer patients with PROMs, fieldwork and biobank assessments. A limitation of this study is, however, that, due to the design of the study, only sociodemographic and clinical characteristics could be compared among groups of patients and caregivers (and not PROMs). Also, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of NET-QUBIC participants were only compared for the main NET-QUBIC component (PROMs, fieldwork, biobank) and a selection of NET-QUBIC subcomponents (tumor biopsy, blood, oral rinse and saliva). Due to patient or caregiver-related factors specific PROMs or subcomponents of the fieldwork assessment may, however, be missing and influence representativeness of data (e.g., specific PROM questions on sexuality may be left open by certain groups of patients or informal caregivers).

Conclusions

Retention rates of the NET-QUBIC study are high. Nevertheless selection may have occurred during the study, which might slightly limit representativeness of NET-QUBIC data and samples. To facilitate representativeness of study findings future cohort studies might benefit from oversampling specific subgroups such as patients with poor clinical outcomes or higher comorbidity and younger caregivers.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- NET-QUBIC

Netherlands Quality of Life and Biomedical Cohort Study

- HNC

Head and neck cancer

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcome measures

- ACE-27

Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27

- WHO

World Health Organization

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

Authors’ contributions

FJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft RBr: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing RBa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing JL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing CL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing RT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing CT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing IV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society [grant number VU 2013–5930] and the Dutch Cancer Society, Alpe Young Investigator Grant [grant number 12820]. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data nor in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the collection and integration of large amounts of personal, biological, genetic and diagnostic information precludes open access to the NET-QUBIC research data. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. On the NET-QUBIC website (www.kubusproject.nl) is described how NET-QUBIC data are made available for the research community.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol has been approved by the medical ethical committee of Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc (the coordinating research center) (2013.301(A2018.307)-NL45051.029.13). Participants provided written informed consent to use and re-use their data and samples in future studies that aim to research HRQOL and improved diagnosis and treatment of HNC.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Teague S, Youssef GJ, Macdonald JA, Sciberras E, Shatte A, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. Retention strategies in longitudinal cohort studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg AR, Bona K, Wharton CM, Bradford M, Shaffer ML, Wolfe J, et al. Adolescent and young adult patient engagement and participation in survey-based research: a report from the "resilience in adolescents and young adults with Cancer" study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(4):734–736. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heppner PP, Armer JM, Mallinckrodt B. Problem-solving style and adaptation in breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(2):128–136. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fosså SD, Dahl AA, Myklebust T, Kiserud CE, Nome R, Klepp OH, et al. Risk of positive selection bias in longitudinal surveys among cancer survivors: lessons learnt from the national Norwegian testicular Cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;67:101744. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leuteritz K, Friedrich M, Nowe E, Sender A, Taubenheim S, Stoebel-Richter Y, et al. Recruiting young adult cancer patients: experiences and sample characteristics from a 12-month longitudinal study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;36:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Cruz PE, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, Kwon JH, Muckaden MA, Bruera E, et al. Factors associated with attrition in a multicenter longitudinal observational study of patients with advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(3):938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey I, de Rooij BH, Mols F, Corsini N, Horevoorts NJE, Eckert M, et al. Cancer survivors who fully participate in the PROFILES registry have better health-related quality of life than those who drop out. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(6):829–839. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00793-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiers S, Oral E, Fontham ETH, Peters ES, Mohler JL, Bensen JT, et al. Modelling attrition and nonparticipation in a longitudinal study of prostate cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0518-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness AR, Waylen A, Hurley K, Jeffreys M, Penfold C, Pring M, et al. Recruitment, response rates and characteristics of 5511 people enrolled in a prospective clinical cohort study: head and neck 5000. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(6):804–809. doi: 10.1111/coa.12548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenix JB, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson HG, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Kasl SV, Bradley EH. Religiousness and major depression among bereaved family caregivers: a 13-month follow-up study. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(4):286–292. doi: 10.1177/082585970602200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Nieuwenhuizen AJ, Buffart LM, Smit JH, Brakenhoff RH, Braakhuis BJ, de Bree R, et al. A comprehensive assessment protocol including patient reported outcomes, physical tests, and biological sampling in newly diagnosed patients with head and neck cancer: is it feasible? Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(12):3321–3330. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2359-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Jansen F, Brakenhoff RH, Langendijk JA, Takes R, Terhaard CHJ, et al. Advancing interdisciplinary research in head and neck cancer through a multicenter longitudinal prospective cohort study: the NETherlands QUality of life and BIomedical cohort (NET-QUBIC) data warehouse and biobank. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):765. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5866-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoso AMM, Jansen F, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, et al. Sleep quality trajectories from head and neck cancer diagnosis to six months after treatment. Oral Oncol. 2021;115:105211. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoso AMM, Jansen F, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, et al. Poor sleep quality among newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(2):1035–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05577-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piai V, Prins JB, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Terhaard CHJ, Langendijk JA, et al. Assessment of neurocognitive impairment and speech functioning before head and neck Cancer treatment. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(3):251–257. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirosevic S, Thewes B, van Herpen C, Kaanders J, Merkx T, Humphris G, et al. Prevalence and clinical and psychological correlates of high fear of cancer recurrence in patients newly diagnosed with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(9):3187–3200. doi: 10.1002/hed.25812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douma JAJ, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Jansen F, Langendijk JA, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, et al. Demographic, clinical and lifestyle-related correlates of accelerometer assessed physical activity and fitness in newly diagnosed patients with head and neck cancer. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2020;59(3):342–350. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1675906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douma JAJ, de Beaufort MB, Kampshoff CS, Persoon S, Vermaire JA, Chinapaw MJ, et al. Physical activity in patients with cancer: self-report versus accelerometer assessments. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3701–3709. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05203-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oriani A, Dunleavy L, Sharples P, Perez Algorta G, Preston NJ. Are the MORECare guidelines on reporting of attrition in palliative care research populations appropriate? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC palliative care. 2020;19(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0506-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal WG, Pessin HA, Radomski JN, Simay Gökbayrak N, Katz AM, et al. Factors associated with attrition from a randomized controlled trial of meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1002/pon.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Hout A, van Uden-Kraan CF, Holtmaat K, Jansen F, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, et al. Role of eHealth application Oncokompas in supporting self-management of symptoms and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors: a randomised, controlled trial recruitment, response rates and characteristics of 5511 people enrolled in a prospective clinical cohort study: head and neck 5000. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(1):80–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Eerenstein SEJ, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Health-related and cancer-related internet use by patients treated with total laryngectomy. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(1):131–140. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04757-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the collection and integration of large amounts of personal, biological, genetic and diagnostic information precludes open access to the NET-QUBIC research data. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. On the NET-QUBIC website (www.kubusproject.nl) is described how NET-QUBIC data are made available for the research community.