Abstract

Introduction:

Continuity is valued by patients, clinicians, and health systems for its association with higher-value care and satisfaction. Continuity is a commonly cited reason for entering primary care; however, it is difficult to achieve in residency settings. We sought to determine the effect of transitioning from a traditional “block” (13 4-week rotations per year) to a “clinic-first” (priority on outpatient continuity) curriculum on measures of continuity in our family medicine residency.

Methods:

For the 3 years prior to and the 4 years following the transition from block to clinic-first curriculum (July 2011-June 2018, n = 51 block resident-years and n = 72 clinic-first resident-years), we measured resident panel size, clinic time, office visits, and both resident- and patient-sided continuity measures. We also defined a new longitudinal continuity measure, “familiar faces,” which is the number of patients that a resident saw at least 3 times during residency.

Results:

The transition from block to clinic-first curriculum increased panel size, clinic time for first- and second-year residents, overall total visits, and total number of clinic visits with paneled patients. Continuity measures demonstrated an increased resident-sided continuity at all training levels, an increase (first-year residents) or unchanged (second- and third-year residents) continuity from the patient perspective, and a near doubling of longitudinal continuity.

Conclusion:

Redesigning our family medicine residency curriculum from a traditional block schedule to a clinic-first curriculum improved our residents’ continuity experience.

Keywords: Keywords:, continuity, curriculum redesign, family medicine residency, Primary care

INTRODUCTION

Continuity of care is universally recognized by patients, clinicians, and health systems as an important component of high-quality care.1,2 Higher levels of continuity between patients and their primary care physicians (PCPs) are associated with better health outcomes, including reduced mortality,3-6 improved patient satisfaction,7,8 and reduced healthcare costs.5,9 Better continuity is linked to fewer missed appointments, decreased duplicative or unnecessary care, and higher rates of appropriate follow-up.10 Moreover, medical students commonly cite continuity as a key reason for pursuing a career in primary care,11,12 and residents report higher satisfaction with increasing levels of continuity.13

Although continuity is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement for residencies in family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics,14-16 there is no specific guidance about how best to measure continuity or what level should be used as a benchmark. There are several well-established measures of continuity that have been applied to residency clinics; however, no measure captures the longitudinal continuity with patients during their training.17,18 Extended periods away from clinic on inpatient rotations is a major scheduling roadblock of continuity for residents. Thus, although continuity in residency training is nominally appreciated, it is not clear how best to measure or improve it.

Starting in June 2014, our family medicine residency underwent a comprehensive curriculum redesign, transitioning from a traditional “block” schedule with 13 4-week blocks, where residents are typically immersed in a specialty with limited amounts of clinic per week, to a longitudinal schedule allowing residents to provide continuous access for a panel of patients throughout 3 years of training (our version of “clinic first”).19-21 The clinic-first training model has been well described elsewhere;21 briefly, it prioritizes continuity of care and increases time spent training in an outpatient residency clinic with high functioning, stable teams. The goals of our curriculum transformation were to 1) better align training with family physician practice following graduation, 2) to teach population health management, 3) to improve the care of patients paneled to resident PCPs, and 4) to improve continuity of care. This required an increase in resident clinic time and shorter, more frequent inpatient experiences to provide patients regular access to their resident PCPs. Inpatient medicine was changed from 4-week blocks to 1-week rotations, and obstetrics was changed from 4-week blocks to 3-4 day/night rotations; the total amount of training in inpatient medicine and obstetrics remained constant. Other block rotations, such as geriatrics and intensive care, were similarly shifted toward longitudinal experiences or shorter blocks without altering the total amount of training. The increase in clinic time was achieved by reducing or eliminating observational specialty care learning experiences. By making these changes, residents were in clinic for a minimum of 3 half-day sessions per week and no more than 8 weekdays between clinic sessions, compared with 1 half-day session per week in many of the blocks in the prior curriculum. Panel sizes were also increased to a goal of 400 patients per resident starting at the beginning of intern year. In this report, we present how these curricular changes affected measures of continuity from resident and patient perspectives and discuss the implications for improving continuity within residency settings.

METHODS

Our 6-resident-per-year, community-based residency program is an affiliate of the University of Washington’s WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Idaho) Family Medicine Residency Network. Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA), previously Group Health Cooperative, is an integrated care delivery system that has served as a model for value-driven care.22 Data for this analysis were extracted from the Epic electronic medical record (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) from July 2011 to June 2018 at KPWA. This analysis was exempted from review by the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board because it was classified as a quality improvement project. Resident and faculty buy-in for this curriculum change was achieved through building consensus on the case for change and a shared responsibility for design by residents and faculty.

The clinic-first curricular schedule is built to match the clinic access requirements of the resident panel sizes (400 patients) as defined by Group Health Cooperative/KPWA primary care standards. The frequency of half-day clinics is adjusted to account for the increase in the number of patients seen per clinic half-day as residents advance in their training. There were no changes in team-based structure (staffing model or team members), resident identity as PCP in the electronic medical record, or resident-specific clinic scheduling processes between pre- and post-curricular changes. Resident clinic schedules are opened at least 3 months in advance, and great efforts are made to avoid rescheduling patients.

For the 3 years before and 4 years after our curriculum change, we calculated multiple measures of continuity as well as clinic metrics, including panel size, number of half-day clinic sessions per week, and number of outpatient visits. Resident panel size fluctuates as patients enter and leave the KPWA health system and switch their PCP; therefore, panel size was calculated as the averages of the panel sizes at one-fourth and three-fourths of the way through the academic year.

Continuity from the clinician perspective can be calculated as the percentage of patients seen by a clinician who are on that clinician’s panel (continuity for physician, PHY).23 For the residency clinic, we calculated the percentage of visits that a resident saw a patient on their panel out of the resident’s total number of outpatient clinic visits for each academic year.

The most commonly used measure of continuity from the patient perspective is the usual provider of care index (UPC),24 which is the percentage of primary care visits with the “usual” provider (ie, the clinician most frequently seen over a given time period). We calculated patient-sided continuity as the percentage of visits for which patients saw their resident PCP out of the total primary care clinic visits for patients paneled to a resident. Primary care visits outside of KPWA are extremely rare. Certain types of primary care visits, including foot care and walk-in retail clinic, are not performed by residents within our system, so these visits were excluded from the denominator.

With residents providing consistent panel access for 3 years, we wanted to measure whether residents were developing longitudinal relationships with their patients. Previously validated continuity measures are cross-sectional and population based and do not describe this relationship, so we also defined and calculated a third continuity measure, “familiar faces” (the number of patients a resident saw 3 or more times over the course of residency). The goal of this measure was to quantify how frequently residents had the opportunity to establish a longitudinal healing relationship with a patient by seeing them at least yearly on average. Caring for a patient on at least 3 separate occasions reflects a combination of 1) longitudinal management of chronic disease, 2) evaluation and management of acute conditions with follow-up, and 3) preventive care. Given that the curriculum transition occurred midway through residency for 2 classes of residents, we assessed the association between the “familiar faces” measure and the clinic-first curriculum based on how many clinic-first years a resident experienced (ie, a given resident class may have experienced 1, 2, or 3 years of clinic-first curriculum).

Because schedules differ systematically among residents at each level of training, we stratified comparisons by resident year. Due to variations in class size and timing of our curriculum transition (occurring for residents at different levels of training), this analysis includes data from 18 first-year residents (R1s), 17 second-year residents (R2s), and 16 third-year residents (R3s) in the block curriculum and 24 R1s, R2s, and R3s in the clinic-first curriculum. With a small sample size, we used nonparametric methods to compare outcomes between the block and clinic-first curricula (Mann-Whitney U test). Lastly, we analyzed the association between the “familiar faces” measure and years of clinic-first curricula using Kendall’s tau rank correlation coefficient, which is a nonparametric ordinal test. Analyses were performed with R version 3.5.1 using the gMWT package and the Kendall package.

RESULTS

Compared with the block model, in the clinic-first curriculum, R1s and R2s spent more half-day sessions in clinic per week, had more office visits, and had larger patient panels; these clinic measures were not significantly different for R3s (Table 1). For all resident levels, the curriculum change was associated with more total office visits by patients on resident panels and a higher average rate of office visits by patients on resident panels.

Table 1.

Resident clinic characteristics before and after the curriculum change from block scheduling to a clinic first model, stratified by resident level

| Block (PRE) | Clinic first (post) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic half-days per week | R1 | 1.8 | 2.9 | < 0.001 |

| R2 | 1.8 | 2.1 | < 0.001 | |

| R3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.56 | |

| Resident no. of office visits per year | R1 | 365 | 589 | < 0.001 |

| R2 | 480 | 561 | < 0.001 | |

| R3 | 569 | 561 | 0.75 | |

| Panel size | R1 | 149 | 294 | < 0.001 |

| R2 | 274 | 383 | < 0.001 | |

| R3 | 329 | 371 | 0.055 | |

| Panel’s no. of office visits per year | R1 | 202 | 510 | < 0.001 |

| R2 | 366 | 649 | < 0.001 | |

| R3 | 457 | 624 | < 0.001 | |

| Visits per paneled patient per year | R1 | 1.34 | 1.73 | 0.0011 |

| R2 | 1.32 | 1.69 | < 0.001 | |

| R3 | 1.38 | 1.68 | < 0.001 |

All values are reported as means. p values are based on Mann-Whitney U test.R1 = first-year resident; R2 = second-year resident; R3 = third-year resident.

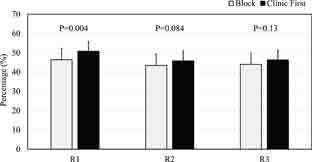

Compared with the block schedule, the clinic-first curriculum was associated with greater resident-sided continuity (PHY) for all resident levels (Figure 1). For R1s resident-sided continuity increased from (mean ± SD) 26.3% ± 9.1% to 43.7% ± 10.4% (p < 0.001), for R2s from 33.0% ± 9.7% to 53.0% ± 10.9% (p < 0.001), and for R3s from 36.3% ± 11.1% to 51.5% ± 10.7% (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Resident-sided continuity in a block versus clinic-first curriculum. The columns represent mean provider-sided continuity during the block and clinic-first curricula. Resident-sided continuity (PHY) is calculated as the percentage of time that a resident saw a patient on their panel out of the resident’s total number of outpatient residency clinic visits in an academic year. Error bars are standard deviation. R1 = first-year resident; R2 = second-year resident; R3 = third-year resident.

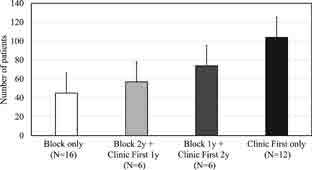

The clinic-first curriculum was associated with greater patient-sided continuity (UPC) for R1s (increasing from 46.4% ± 4.3% under the block curriculum to 50.8% ± 4.5% under the clinic-first curriculum, p = 0.004), but there was no statistically significant change for R2s and R3s (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient-sided continuity in a block versus clinic-first curriculum. The columns represent the mean patient-sided continuity during the block and clinic first curricula. Patient-sided continuity (also known as usual provider continuity [UPC]) is calculated as the percentage of time that patients saw their resident primary care provider for an office visit out of the patients’ total primary care clinic visits during the academic year. R1 = first-year resident; R2 = second-year resident; R3 = third-year resident.

The number of patients seen at least 3 times in clinic by a resident throughout training (“familiar faces”) was correlated with a greater exposure to the clinic-first curriculum (p < 0.001), with the lowest number among residents who experienced the block curriculum only and the highest among residents who completed 3 years of clinic-first residency training (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

“Familiar Faces” continuity with increasing exposure to clinic first curricula. Columns represent mean “Familiar Faces” continuity score, which is the number of patients a resident saw at least 3 times in clinic throughout residency. “N” represents the number of residents whose training is characterized by the above curriculum experience.

DISCUSSION

We found that switching from a traditional block to a clinic-first curriculum improved patient-clinician continuity in the residency clinic. By making the resident clinic the first priority in the design and implementation of the curriculum, we significantly increased the amount of time in clinic, the number of patients residents saw on their panel, the size of resident panels, and the number of patients residents cared for multiple times during residency. Prior reviews of the effects of curriculum innovations on continuity measures within primary care residency clinics have shown conflicting results.18 This is likely because of differences in how continuity was measured, the length of the curriculum (outpatient block vs entire residency), a lack of tools to measure and report continuity, and the challenges of providing continuous outpatient access by residents. Our experience illustrates the value of emphasizing learning in the residency continuity clinic, the complexity and limitations of the existing continuity measures, and the need for further emphasis on continuity in residency training.

Resident-sided continuity describes how frequently residents see patients for whom they are the PCP and is largely affected by panel size.18 The intentionally larger panel sizes in the clinic-first curriculum were expected to increase resident-sided continuity because there were more paneled patients to fill appointments, and this is what we found. The curriculum increased resident-sided continuity at all training levels, with the largest effect for R1s, nearly doubling from 26% to 44%. However, in spite of similar panel sizes and time in clinic for R3s before and after the curriculum change, resident-sided continuity increased, which suggests the role of other factors such as fewer large time gaps between clinics, the amount of time residents provide consistent clinic access (3 years), and potentially greater panel engagement. In our clinic-first curriculum now, residents see their own patients about half of the time, which improves the resident continuity experience.

Patient-sided continuity describes how often primary care visits are with a patient’s assigned PCP. This measure is a balance between panel size and PCP availability. If panel sizes were increased without a concomitant increase in clinic time, then we would anticipate patient-sided continuity would decrease as more patients compete to fill a limited number of appointments. However, despite larger panel sizes, patient-sided continuity remained about the same for all 3 years. This suggests that the increases in clinic time were commensurate with increases in panel size and that patients were able to see their resident-PCPs about half the time. A higher frequency of clinic sessions is instrumental for patient-sided continuity and the frequency with which residents can be scheduled is limited by both the curriculum and the relative amount of time residents are in clinic compared with other locations.

Interestingly, patients paneled to residents in the clinic-first curriculum had 25% more primary care visits compared with those on resident panels in the block curriculum. This could be due to a higher level of patient engagement and follow-up because residents were more regularly available to patients in the clinic-first curriculum for a longer period of time. This may also have been secondary to a higher level of medical complexity of patients on the resident panels over time.

Our residents have previously described the personal and educational value of forming longitudinal healing relationships with patients in the clinic-first curriculum.19,20 However, none of the continuity measures detected this. Consequently, we developed a new measure to capture the longitudinal continuity experience by calculating how often residents saw an individual patient at least 3 times. This “familiar faces” measure nearly doubled under the clinic-first curriculum compared with the traditional block model. Building relationships through repeated encounters and witnessing how conditions and patients evolve over time are fundamental to resident learning and, we hypothesize, are related to the previously seen improved outcomes, decreased cost, and patient satisfaction; without this new measure we could not assess this important component of learning and service, and we hope that this may be helpful for other programs.

The main limitation of our results is that this study was observational. Residents were not randomized, and there was no control group to assess the impact of other variables in the residency clinic and care delivery system that could have affected the continuity measures over the same time period. Also, the curriculum change took place at a single, urban, family medicine residency program within an integrated care delivery system, so our findings may not generalize to other residency programs. We plan to assess how the curricular changes affected objective measures of resident well-being and patient quality metrics. Finally, the increased continuity observed was modest: 50% continuity for patients or providers is not ideal. Compared with other PCPs, residents are just not in clinic enough to be reliably available when needed; resident PCPs in our system are arithmetically equivalent to a 0.22 full-time-equivalent provider. With relatively few appointment slots available per week, patients have limited access to resident PCPs. Interestingly, when we compared patient-sided continuity among faculty and other nonfaculty PCPs in the same clinic, the measure hovered between 45% and 55% for most providers, so it is possible that this low patient-sided continuity may reflect larger issues with access and scheduling in our system that are not well aligned to promote continuity.

CONCLUSION

Although panel size and clinic time have conflicting effects on continuity from provider and patient perspectives, by increasing both, we observed that the clinic-first curriculum increased overall time in clinic, the number of paneled patients residents saw, the proportion of the time residents saw their own patients, and the number of patients seen multiple times. There is a glaring gap between the well-established value of continuity in primary care and its measurement and integration into the design of training programs. There is also a limitation in continuity that residents and patients can experience when the minority of time residents spend in training is in the clinic. As a pillar of primary care, there is an urgent need to redesign primary care residency curricula to promote patient-provider continuity and leverage the value it brings to health care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jamie Balducci and her team at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Plan, for assistance with data acquisition.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations: KPWA, Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA); PCP, primary care physician; PHY, continuity for physician; R1, first-year resident; R2, second-year resident; R3, third-year resident; UPC, usual provider of care; WWAMI, Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Idaho

Funding: There was no external funding source.

Author Contributions: Kathleen J. Paul, MD, MPH, participated in the study design, drafted the manuscript, and participated in the manuscript’s critical review and submission. Brandon H. Hidaka, MD, PhD, participated in the drafting of the manuscript, designed and performed the statistical analysis, and participated in the manuscript’s critical review and submission. Paul Ford, MS, participated in the study design, acquired the data and participated in the manuscript’s critical review. Carl Morris, MD, MPH, participated in the study design and the manuscript’s critical review and submission.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014 Mar-Apr;12(2):166-71. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1616, PMID:24615313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield BH. Primary care: Balancing health needs, services, and technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leleu H, Minvielle E. Relationship between longitudinal continuity of primary care and likelihood of death: Analysis of national insurance data. PLoS One 2013 Aug;8(8):e71669. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071669, PMID:23990970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolinsky FD, Bentler SE, Liu L, et al. Continuity of care with a primary care physician and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010 Apr;65(4):421-8. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/glp188, PMID:19995831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin DW, Cho J, Yang HK, et al. Impact of continuity of care on mortality and health care costs: A nationwide cohort study in korea. Ann Fam Med 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):534-41. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1685, PMID:25384815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker R, Freeman GK, Haggerty JL, Bankart MJ, Nockels KH. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2020 Sep;70(698):e600-e611. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp20X712289, PMID:32784220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: A critical review. Ann Fam Med 2004 Sep-Oct;2(5):445-51. DOI: 10.1370/afm.91, PMID:15506579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjortdahl P, Laerum E. Continuity of care in general practice: Effect on patient satisfaction. BMJ 1992 May;304(6837):1287-90. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.304.6837.1287, PMID:1606434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss LJ, Blustein J. Faithful patients: The effect of long-term physician-patient relationships on the costs and use of health care by older Americans. Am J Public Health 1996 Dec;86(12):1742-7. DOI: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1742, PMID:9003131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shortell SM, May N. Continuity of medical care. Medical Care 1976 May;14(5):377-91. DOI: 10.1097/00005650-197605000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students' career choices regarding internal medicine. J Am Med Assoc 2008 Sep;300(10):1154-64. DOI: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1154, PMID:18780844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon DJ, DiPette DJ. Specialty choice among students entering the fourth year of medical school. Am J Med Sci 1994 Nov;308(5):284-8. DOI: 10.1097/00000441-199411000-00005, PMID:7977447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blankfield RP, Kelly RB, Alemagno SA, King CM. Continuity of care in a family practice residency program. Impact on physician satisfaction. J Fam Pract 1990 Jul;31(1):69-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in internal medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in family medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. BMJ 2003 Nov;327(7425):1219-21. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219, PMID:14630762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker J, Payne B, Clemans-Taylor BL, Snyder ED. Continuity of care in resident outpatient clinics: A scoping review of the literature. J Grad Med Educ 2018 Feb;10(1):16-25. DOI: 10.4300/jgme-d-17-00256.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes K, Morris CG. Clinic first: Prioritizing primary care outpatient training for family medicine residents at group health cooperative. J Gen Intern Med 2015 Oct;30(10):1557-60. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-015-3272-z, PMID:26224150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundar KR. The gift of empanelment in a "clinic first" residency. Ann Fam Med 2018 Nov;16(6):563-5. DOI: 10.1370/afm.2307, PMID:30420375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R, Barnes K, Bodenheimer T. Clinic first: 6 actions to transform ambulatory residency training. J Grad Med Educ 2016 Oct;8(4):500-3. DOI: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00398.1, PMID:27777657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson EB. Group Health Cooperative--one coverage-and-delivery model for accountable care. N Engl J Med 2009 Oct;361(17):1620-2. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp0909021, PMID:19846846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darden PM, Ector W, Moran C, Quattlebaum TG. Comparison of continuity in a resident versus private practice. Pediatrics 2001 Dec;108(6):1263-8. DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1263, PMID:11731646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breslau N, Reeb KG. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J Med Educ 1975 Oct;50(10):965-9. DOI: 10.1097/00001888-197510000-00006, PMID:1159765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]