Abstract

Introduction:

Food insecurity (FI) is common in families with young children. People experiencing FI have worse health outcomes related to behaviors (obesity, diabetes management, etc) than people who are food secure. This study explores strategies that parents on limited incomes use to feed their children, their understanding of nutrition for their children, and the social factors contributing to or alleviating FI.

Methods:

We conducted key informant interviews with 20 parents of young children from Mesa County, Colorado who were receiving benefits from the Woman, Infants, and Children program. Participants were between 21 and 32 years of age and 9 reported Latinx heritage. Questions addressed parents’ understanding of how FI affects their ability to enact healthy behavior and their experience of caring for children while facing FI. Transcripts were analyzed using a grounded theory approach, using Atlas.ti for organization.

Results:

Four primary themes emerged: participants have knowledge around healthy behaviors; parents use detailed budgeting schemes to provide for their families; parents are invested in their children’s future; and while parents often rely on assistance programs, they also have a strong sense of responsibility to provide.

Discussion:

Parents know what they can do to promote health but face significant obstacles in implementing their knowledge. Assumptions are often made that health behavior is primarily about personal choice and motivation, but system-level factors prevent implementation of healthy behavior.

Conclusion:

Parents are aware of the connection between nutrition and outcomes and work to ensure opportunities for good health but are limited by system-level factors.

Keywords: food insecurity, health behaviors, health knowledge, nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity (FI) is defined as a household level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food, implying both quantity and quality of food.1 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, FI affected 12% of the US population and around 16% of families with children.2 FI is associated with poor health outcomes in both children and adults. In children, household FI has been associated with poorer parental ratings of their children’s overall health and increased number of hospitalizations,3 as well as developmental, behavioral, and academic challenges.4 In adults, experience of FI at some point during childhood or young adulthood is associated with higher body mass index, depressive symptoms, and disordered eating.5 FI is also associated with poor nutritional quality,6,7 possibly contributing to poor health in families with children.

Previous research indicates that parents in families experiencing FI are interested in discussing prevention and health behavior change with their children’s providers.8 Many of the poor health outcomes associated with FI are in part related to health behaviors, pointing to a possible mismatch between what people know about healthy behavior and what they are actually able to put into practice.

Building on these findings, we were interested in exploring how families with young children understand and attempt to mitigate the effects of FI on their health and strategies they use to ensure good nutrition and health for their families. There have been some studies examining strategies families use to meet needs and avoid hunger while experiencing FI. For example, parents experiencing FI protect their children from hunger by purchasing inexpensive, calorie-rich but nutrient-poor foods, and parents are more likely to feed children first or forego their own needs, such as medical care, to be able to purchase adequate amounts of food.9 In addition, some qualitative research done with primarily urban populations has revealed strategies to alleviate FI such as cooking in large groups or sharing of food resources.10

However, there is very little research on the approach families experiencing FI use to safeguard their health, particularly focusing on their approach to healthy nutrition and other behaviors given their social context. This paper reports the results of qualitative inquiry to understand health behaviors of families with young children facing FI in western Colorado.

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted in Mesa County, Colorado. Mesa County, with a total population of 150,000 and covering more than 3,300 square miles is comprised of one urban center (Grand Junction) surrounded by several rural communities. Approximately 81% of the Mesa County population is non-Hispanic White and 15% of Mesa County residents currently live in poverty compared with 11% statewide.11

Institutional Review Board Approval

This study received institutional review board approval through the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was explained and obtained prior to interviews.

Sampling Strategy and Recruitment

As the research was intended to explore the lived experience of families with young children who experience FI, the sampling strategy was purposive to include parents of young children receiving food assistance. Participants were recruited at the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program office in Mesa County, Colorado. Potential participants received an informational flyer about the study from WIC staff. Interested parents gave their contact information to WIC staff and were contacted by the investigator by phone to arrange an interview. Interviews were conducted in private spaces, generally when the participants came in for a WIC appointment. No one else was present during the interview besides the participant(s) and the researcher except participants’ young children (under the age of 5).

Participants

We conducted 17 interviews, 3 of which were with male-female couples for a total of 17 female and 3 male participants. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 32 years. Nine participants reported Hispanic ethnicity. We conducted the interviews in English, and they were recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Research Tools

The research team formulated the question guide based on our previous research indicating increased interest in discussing health behaviors among food-insecure parents compared with food-secure parents, as well as a review of the literature on FI in families. The interview guide was pilot tested with 2 representatives of the target population. Participants also completed a FI screening tool12; all except 1 screened positive for household FI with 11 also reporting child FI.

Timeframe

Interviews were conducted between April 2017 and January 2018. Each interview lasted 30 to 45 minutes. Thematic saturation was reached.

Analysis Team and Approach

An emergent, grounded theory approach was used in analysis,13 as this approach allows new information about previously studied concepts to emerge. All transcripts were double-coded. AN analyzed all 17 transcripts, and each transcript was also coded by 1 other team member with experience in qualitative interview analysis and health disparities (BM, PP-B, or EB). The researchers met repeatedly to discuss codes, individual transcripts, and emerging themes. ATLAS.ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used for data sorting and management.

Theoretical Approach

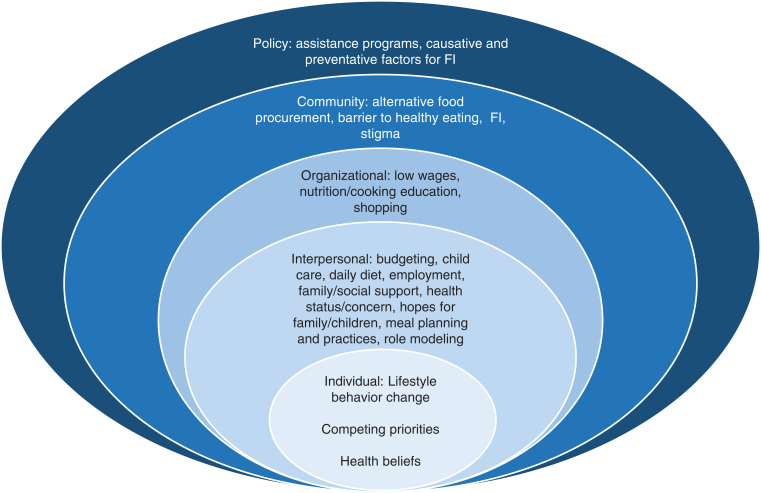

As we were interested in how families with FI navigate health behaviors in their social context, we used the social-ecological model in development of codes and themes. We started with an a priori list of codes developed according to individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy implications of FI14,15 and iteratively added more. See Figure 1 for an example of codes for each level.

Figure 1.

Codes mapped to the Social-Ecological Model. FI = food insecurity.

RESULTS

Themes

The themes that emerged from our data did not map to separate spheres of the social ecological model but reflect the interplay between these constructs and the reality that FI impacts and is impacted by both individual and social factors.

Four primary themes emerged, as well as some subthemes.

Theme 1

Participants generally had knowledge of healthy eating and other behaviors but struggled to implement these behaviors in their family’s lives because of expense and income instability, health or other circumstances, and competing priorities.

Implementing Health Knowledge in Light of Expense and Income Instability

The participants in this study were almost uniformly able to describe a healthy diet for young children. They were also keenly aware that the meals they served their children were not as nutritious as they could be. The general explanation for this was that they could not afford to take “risks” on healthier foods that their kids might not eat or that they could not afford healthy options like fresh fruit and vegetables.

“I will buy vegetables, but … the meat is really the most expensive. So, if we have meat, we barely have vegetables on the side. And if we have vegetables, they’re canned…. I always just think that the original vegetable is always better than the canned.”

Parents also describe stretching meals at the end of a benefit or pay cycle with increased simple carbohydrates like pasta or rice or being dependent on foods provided by food banks or school-based programs. They recognize that these highly processed foods are not healthy, but often have no other options.

“Once the benefits and stuff like that run out, then we kind of go to not so healthy. You know, I will buy stuff like the SpaghettiOs, and a bunch of the canned foods for backup because the meat gets really expensive, the produce is really expensive, and it doesn’t last very long.”

“I guess just feels kinda like a bummer, you know. You want to eat chicken, you wanna eat steak or something. You always eat potatoes ’cause there’s lots of potatoes; there’s lots of rice and beans. We used to be homeless for a while … so we just kinda adapt to whatever there is … like, don’t think about it too much as long as we eat, you know.”

Health

Many participants mentioned personal or family health concerns and were aware of the effects of FI and resultant poor nutrition on their health.

“You know, I realized that my—my health—I have diabetes. My children are in the higher percentiles for weight, and I just realized that it’s our fault because we have allowed … whatever we feel like eating, you know, more convenient things that we’re not good for us.”

Competing Priorities

Parents also described competing priorities and juggling multiple expenses. Parents were aware of things that would improve the health of their families but had to balance this with financial and logistical realities.

“I need to have more concerted effort to do like more cardiovascular things where I maybe go ridin’ bikes with him where … Um [sighs] just being so busy and not planning it into the day. It just seems like life like takes over. Also circumstances, where we live.”

“You know, I coupon a lot, and I noticed with that it was very easy to get coupons for like the juice, fruit rollups, gushers, all those things to get ’em—even free. And I think it’d be really nice if there was like coupons for the healthier things. You know, ’cause even while I was couponing I was stocking up on those free things.”

Often small, unexpected expenses had long term negative effects on finances and consequently, health behavior and nutrition.

“And then my car has broken down recently. The last fix was $700…. And then also catching up, ’cause there were a few months where I fell behind on Xcel [utilities], so I used my credit card to get caught up.”

Theme 2

Parents used detailed budgeting schemes, saved to make sports and other activities possible, and did their best to model healthy behavior.

Detailed Budgeting Schemes

Participants described detailed meal planning and budgeting as a strategy that helps decrease the likelihood of running out of food but does not eliminate FI. Some participants described making meal plans in advance, buying in bulk, and cooking things like pasta from scratch in an effort to save money.

“Well, WIC gives us a certain amount of vegetables, so we try to make sure we get those fruits and vegetables, and then me and my significant other put money aside each check to make sure that we have food to feed our family for the month.”

“I mainly shop for canned goods and bulk food items to where I always have food because I don’t like ever being…feeling that way that, I mean, we’re gonna go hungry and there’s no food…If I don’t shop for convenience, I have food all month.”

Saving to Allow for Other Health-Promoting Activities

“Well, instead of getting, like, quality meats [laughs], we go to Walmart and get the cheaper stuff. Rather than spending it on that, so then that way we can get—afford the school stuff, the softball and basketball. We do try to let them play at least one sport a year.”

Modeling Healthy Behavior

“Just start eating them yourself and they’ll be like, ‘Oh what’s mom eating? I want some of that.’”

“Um I would say they learn nutrition, so they’re not, ‘Oh hey let’s go eat out,’ five times a week … there are some weeks when I just don’t wanna cook. We’ll just go get something, but other weeks I say … we can cook together. My 5-year-old always wants to help, so we have like a little spot just for him that he can cook, and we have like these little practice knives that he can cut his own foods, so just get him to teach him how to eat right instead of eating McDonald’s every day.”

Theme 3

Parents are invested in their families’ future and interested in learning opportunities, often because they are trying to improve on what they experienced as children.

They often mentioned that education or support around eating a nutritious diet on a limited budget or managing household finances would be helpful.

“Like WIC, the cooking class is really cool. You know cooking for your family. Maybe classes on shopping. How to shop for food, what to shop for on a budget. Maybe different budgeting classes.”

Many participants described experiencing significant hardship as children themselves. They were committed to providing better opportunities for their children.

“When I was little, we really didn’t have any money at all. My parents would work, but they worked pretty much to pay bills … my mom would usually be sleeping during the day, and then my dad would work all day, and then come home and try and make something, so if anything, we would just find whatever we could eat and just eat it [laughs]. Now, we sit down for dinner every night. I just tried to make it … everything that I wanted when I was little.”

“I don’t want … us to be like my family was, and I want my family to be together forever, just be able to eat healthy and enjoy our lives. I don’t wanna put my kids in harm.”

In addition, parents often had career or educational goals, again motivated in part by desire for a life for their kids that was different from their own. They recognized that achieving these goals required short-term sacrifice for long-term gain. This was particularly true for parents who were pursuing education in the hopes of jobs with higher salaries in the future, leading to increased family stability.

“Well, of course it’s hard right now, but it’ll get easier later. And the job, like my school, it’s like a good opportunity—I could get hired right when I graduate. So basically [sigh], we just have to really work at it. It’ll pay in the long run.”

Theme 4

Parents rely on family and social network support or organizations, including food assistance programs, to support healthy behaviors in their families, but report a sense of responsibility to provide as well.

Family or Social Network Support

Participants also described relying on family and social networks to keep food on the table. Often this seemed to be a preferred avenue for making ends meet over food banks or other food assistance programs.

“I’d probably ask family first, I have a really supportive family, so they’d probably help first, and then if not, we would probably go to food stamps for the time being”

“We’ll last like a couple days without certain food. You know, we might last 2, 3 days without milk, and one of us will bring it or a couple days without bread, and we’ll just bring it after that.”

Organizational Support

Participants reported receiving significant support from food assistance programs, particularly around nutrition education.

“Um I have learned actually a lot coming here. I was kind a bad like [laughs] way back when [laughs] … when my son was little, but we’ve learned like balanced meals like fruits, vegetables, stuff like that, and now we let him pick out his own vegetables … he actually loves Brussels sprouts.”

“Well, we also make use of some of the programs the state has the offer. Like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). It’s a very good program. I mean you don’t have to be ashamed to be a part of it. I mean if you use it for what it’s needed for like providing for your family when you ain’t got enough income.”

Others expressed trying to stay off assistance programs unless absolutely necessary, both because of hesitancy to use government programs and the perception that food quality was low when received from community programs.

“I had food stamps at one point, but I try not to live off the … He’s [my dad] always been a person that’s liked to work, and you know work hard and feed his family, or make sure that we have food on the table, and make sure that we’re not … you know using assistance if we don’t absolutely need it.”

“I really don’t like going to certain food banks. I feel like what they give you is pretty much crap, in my personal opinion. They give you yogurt that’s pretty much about ready to expire. They give you bread that’s stale. They’re not giving you like meats. They’re not giving you anything that like solid that will hold down baby’s belly.”

Sense of Responsibility

Participants also described helping those in need and believed their experiences could benefit others.

“Well one came to me, and said, ‘I don’t know what to do. I haven’t …’ you know just kind of divulged that they really needed the help … so I said you know this is the information. I figure I’ve been through what I have for a reason. I used to be upset a lot, and not understand why, but I’ve kind of come to the realization that … with everything that’s gone on in my life I can use my experience to help other people and maybe get through to somebody.”

They also described self-sacrifice so that other family members would not go hungry.

“I think it’s the days that he doesn’t eat at school he comes home really hungry, and he eats more. So, then my husband will eat. And now my daughter is kind of—I’m introducing the food that I cook for my family to her, too. And so, I hate to say this, but I’m kind of like the one that is left out because I’m serving my family.”

DISCUSSION

There is evidence that lack of nutrition knowledge contributes to FI and poor nutritional status in low-income families.16 However, the parents in our sample who are facing FI were aware of what foods and activities promote health in their children and were able to describe how they could improve their families’ health. They reported spending a lot of time and energy determining how to best promote health in their families. However, due to limited economic and personal bandwidth, they were often forced to rely on nutritionally poor foods and could not always support health-promoting behaviors in their families.

Another explanation for FI is poor budgeting or meal planning.17 While some research has revealed a lack of financial literacy among people who experience FI, we found that parents use elaborate budgeting strategies and planning, often being hyperaware of where they are spending money and the choices they have to make. In fact, this strategizing and budgeting takes great amounts of mental energy and time. People facing FI could be seen as modern day “hunter gatherers” in their approach to food, often having to go to great lengths to procure food, which draws energy and resources away from other activities that might help to ensure a more secure future (eg, education).

Perhaps contrasting with other studies, this study confirms what we found in a previous quantitative study: that food-insecure parents are interested in healthy behavior and health improvement but are not always able to enact healthy choices and behaviors due to factors often outside their control. This study sheds lights on some of the factors that keep awareness and interest in healthy lifestyles from translating into healthy behaviors. This inability to enact healthy behaviors likely reflects basic theories like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs18; families are concerned primarily with avoiding hunger and making ends meet. However, our analysis also indicates that while people are working to meet their basic needs, they are very aware of higher level needs such as improving nutrition for health. We also found evidence of future-oriented thinking and trying to mitigate current poverty by making investments in their future or the future of their children through short-term sacrifice.

Our research also demonstrates the important role of community and programmatic support in the lives of families facing FI, particularly during times of transition, such as parental pursuit of higher education. This type of support is threatened with current policy proposals to cut food assistance programs to non-working adults; cutting these programs may lead parents of young children to decide not to pursue their long-term goals for financial security, thus perpetuating continued FI and ultimately poor health outcomes. In addition, given the extended family and social support our participants reported, our study indicates a need to evaluate families in a larger context, recognizing the potential and importance of peer-to-peer support and education around nutrition and social needs. For example, participants may benefit from education directed at healthy eating on a budget, as there are options for inexpensive healthy foods that are not perishable that were not mentioned by participants, such as dried beans, lentils, and frozen vegetables.

Finally, we believe our data and analysis are trustworthy given that participants endorsed several well-documented qualitative findings from previous research on FI in low-income families, particularly concerning parental choice to feed children prior to feeding themselves and the dietary effects of a fluctuating income.19 While our study is qualitative in nature, and therefore cannot be generalized to other populations, we believe we have captured a snapshot of life for food-insecure families in western Colorado.

CONCLUSION

FI results in complex struggles between meeting daily needs and trying to engage in health-promoting behaviors. Families who experience FI have very limited resources to put toward healthy food and other elements of a healthy lifestyle and often have to make practical choices like feeding their children filling, non-nutritious foods to avoid hunger. They are often faced with short-term decisions that reduce the likelihood of escaping poverty and FI in the future. Future research and programmatic efforts to determine how to better support low-income families in providing nutritious foods and engaging in healthy behaviors could result in improved health outcomes on individual and societal levels.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Statement: Andrea Nederveld, MD, MPH, received funding from the Rocky Mountain Health Foundation for this study.

Authors’ Contributions: Andrea Nederveld, MD, MPH, conducted all interviews, reviewed and analyzed all transcripts, lead discussions on analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Elizabeth Bayliss, MD, MSPH, assisted Dr Nederveld with study design, analyzed one-third of the transcripts, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Phoutdavone Phimphasone-Brady, PhD, and Bridget Marshall, DNP, each analyzed one-third of the transcripts and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Abbreviations: FI = food insecurity; WIC = Women, Infants, and Children

References

- 1.USDA. Definitions of Food Security. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx#:∼:text=Food%20insecurity%E2%80%94the%20condition%20assessed,may%20result%20from%20food%20insecurity

- 2.USDA. Household Food Security in the United States in 2017. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022

- 3.Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr 2004. Jun;134(6):1432–8. DOI: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankar P, Chung R, Frank DA. Association of food insecurity with children’s behavioral, emotional, and academic outcomes: A systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2017. Feb/Mar;38(2):135–50. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darling KE, Fahrenkamp AJ, Wilson SM, D’Auria AL, Sato AF. Physical and mental health outcomes associated with prior food insecurity among young adults. J Health Psychol 2017. Apr;22(5):572–81. DOI: 10.1177/1359105315609087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mello JA, Gans KM, Risica PM, Kirtania U, Strolla LO, Fournier L. How is food insecurity associated with dietary behaviors? An analysis with low-income, ethnically diverse participants in a nutrition intervention study. J Am Diet Assoc 2010 Dec;110(12):1906–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Leung CW, Epel ES, Ritchie LD, Crawford PB, Laraia BA. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014. Dec;114(12):1943–53.e2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.06.353 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nederveld A, Cox-Martin M, Bayliss E, Allison M, Haemer M. Food insecurity and healthy behavior counseling in primary care. J Health Dispar Res Pract 2018. Fall;11(3):49–58. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol11/iss3/4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nord M, Parker L. How adequately are food needs of children in low-income households being met? Child Youth Serv Rev 2010. Sep;32(9):1175–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers N, Sood A, Alolayan Y, et al. Coping with food insecurity among African American in public-sector mental health services: A qualitative study. Community Ment Health J 2019. Apr;55(3):440–7. DOI: 10.1007/s10597-019-00376-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Mesa County, Colorado. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/mesacountycolorado

- 12.USDA. Survey Tools. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools/

- 13.Charmaz K. Grounded theory as an emergent method. In: Handbook of emergent methods. Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P, editors. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008; p 155–72 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green LW, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. Am J Health Promot 1996. Mar-Apr;10(4):270–81. DOI: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol 1977;32(7):513–31. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begley A, Paynter E, Butcher LM, Dhaliwal SS. Examining the association between food literacy and food insecurity. Nutrients 2019. Feb;11(2):445. DOI: 10.3390/nu11020445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang Y, Kim J, Chatterjee S. The association between consumer competency and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation on food insecurity. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017. Sep;49(8):657–66.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maslow AH. Higher and lower needs. J Psychol 1948. Apr;25(2):433–6. DOI: 10.1080/00223980.1948.9917386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nord M. Youth are less likely to be food insecure than adults in the same household. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2013. Jun;8(2):146–63. DOI: 10.1080/19320248.2013.786667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]