Abstract

Background.

Globally mobile populations are at higher risk of acquiring geographically restricted infections and may play a role in the international spread of infectious diseases. Despite this, data about sources of health information used by international travelers are limited.

Methods.

We surveyed 1,254 travelers embarking from Boston Logan International Airport regarding sources of health information. We focused our analysis on travelers to low or low-middle income (LLMI) countries, as defined by the World Bank 2009 World Development Report.

Results.

A total of 476 survey respondents were traveling to LLMI countries. Compared with travelers to upper-middle or high income (UMHI) countries, travelers to LLMI countries were younger, more likely to be foreign-born, and more frequently reported visiting family as the purpose of their trip. Prior to their trips, 46% of these travelers did not pursue health information of any type. In a multivariate analysis, being foreign-born, traveling alone, traveling for less than 14 days, and traveling for vacation each predicted a higher odds of not pursuing health information among travelers to LLMI countries. The most commonly cited reason for not pursuing health information was a lack of concern about health problems related to the trip. Among travelers to LLMI countries who did pursue health information, the internet was the most common source, followed by primary care practitioners. Less than a third of travelers to LLMI countries who sought health information visited a travel medicine specialist.

Conclusions.

In our study, 46% of travelers to LLMI countries did not seek health advice prior to their trip, largely due to a lack of concern about health issues related to travel. Among travelers who sought medical advice, the internet and primary care providers were the most common sources of information. These results suggest the need for health outreach and education programs targeted at travelers and primary care practitioners.

Globally mobile populations are at higher risk of acquiring geographically restricted infections, such as yellow fever, dengue fever, and malaria, as well as infections that are more common in resource-poor areas of the world, such as typhoid fever, hepatitis A, and diarrheal diseases. In addition to the personal health risks, mobile populations may also pose a health risk to the local community by facilitating the dissemination of pathogens across borders. The rapid worldwide spread of novel influenza strains1 and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)2 represents two recent examples of the role of globally mobile populations in the spread of disease.

To improve health interventions targeted at globally mobile populations, an improved understanding of their health practices is needed. In particular, identifying sources of health advice and barriers to appropriate pre-travel care is essential. In this study, we surveyed US residents traveling to international destinations who were departing from Boston Logan International Airport in 2009. The purpose was to collect demographic data on travelers, to identify sources of health information, and to understand barriers to the pursuit of health information prior to departure.

Methods

We surveyed a convenience sample of travelers awaiting departure from Boston Logan International Airport on an international flight or on a domestic flight with an immediate connection to an international flight. Representatives of the Boston Public Health Commission, the Massachusetts Port Authority, and the Boston Logan Airport Fire Rescue and Police were involved in the development and administration of the surveys. Surveys were administered from February through August 2009. Survey respondents filled out questionnaires regarding their destination and provided demographic data about themselves and any travel companions. Only one survey was collected per traveling group or family. We questioned individuals as to whether they had pursued health information from specific sources, including the internet (in particular the CDC Travelers’ Health website), primary care providers, travel medicine specialists, travel agents, employers, and travel publications. We also asked them to indicate whether they were carrying prescription medications related to their trip. The majority of surveys (>90%) were administered in English; surveys were also available in Spanish, Portuguese, French Creole, Chinese, Hindi, and Arabic.

Geographic destinations were classified into income categories according to the 2009 World Bank World Development Report (http://econ.worldbank.org).3 We divided survey respondents into those traveling to countries classified as low and low-middle income (LLMI) or upper-middle and high income (UMHI) by the World Development Report. Travelers were classified as “visiting friends and relatives” (VFR) according to a definition outlined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), ie, an immigrant to the United States who returns to his or her homeland, a lower income country, to visit friends or relatives.4 Also included in the VFR category were family members who were born in the United States. Travelers who did not meet the above definition of VFR travel were classified as “visiting family.”

Survey data were entered and managed in Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). We performed bivariate and multivariate analyses using SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and SUDAAN 10.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). To test for significant differences between groups, we used two-sided t-tests (continuous variables) or chi-square tests (categorical variables), as appropriate. We performed a logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between demographic factors [age (continuous), gender (male or female), country of birth (foreign-born or US-born), fellow travelers (traveling alone or not), duration of travel (>14 days or ≤14 days), and purpose of travel] and the likelihood of pursuing health information among travelers to LLMI countries.

The Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee approved this study. No personally identifiable information was collected from study respondents.

Results

A total of 1,254 travelers, all of whom resided permanently in the United States, completed the survey. A total of 476 survey respondents (38%) were traveling to LLMI countries and 778 survey respondents (62%) were traveling to UMHI countries. The four most common LLMI country destinations among survey respondents were the Dominican Republic (n = 129), India (n = 55), China (n = 47), and Turks and Caicos (n = 43). A total of 61 survey respondents were visiting countries in Africa, including 45 visiting sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 1 compares demographic characteristics of survey respondents traveling to LLMI countries and UMHI countries. Travelers to LLMI countries differed significantly from travelers to UMHI countries in a number of attributes. In particular, travelers to LLMI countries were younger and more likely to be foreign-born. The four most common foreign birthplaces among survey respondents were India (n = 42), the Dominican Republic (n = 41), China (n = 16), and Haiti (n = 15). Travelers to LLMI countries pursued trips of longer duration; visiting family and performing volunteer work were more frequently reported as the purpose of travel to LLMI countries (Table 1). Of note, 98 (21%) travelers to LLMI countries fit the CDC criteria for VFR.4 Travelers to LLMI traveled more frequently with children under the age of 5 (17% of respondents to LLMI countries vs 8% of respondents to UMHI countries, p = 0.02). Overall, 54% of survey respondents traveling to LLMI countries pursued any health information prior to departure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents, by income classification of destination country*

| LLMI countries | UMHI countries | p Value ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 476 (38%) | 778 (62%) | |

| Age of primary respondent (years; median, range) | 43 (10–89) | 46 (12–96) | 0.01 |

| Gender (male) | 219 (46%) | 331 (43%) | 0.22 |

| Foreign-born | 176 (38%) | 146 (19%) | <0.0001 |

| Traveling with family | 180 (38%) | 404 (52%) | <0.0001 |

| Duration of travel (days) | |||

| 1–7 | 132 (28%) | 354 (46%) | <0.0001 |

| 8–14 | 162 (34%) | 322 (41%) | |

| 15–28 | 120 (25%) | 60 (8%) | |

| >28 | 61 (13%) | 41 (5%) | |

| Purpose of trip† | |||

| Vacation | 251 (53%) | 586 (75%) | <0.0001 |

| Visiting family | 134 (28%) | 124 (16%) | <0.0001 |

| VFR | 98 (21%) | N/A | — |

| Business | 63 (13%) | 87 (11%) | 0.29 |

| Volunteer work | 62 (13%) | 4 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Education/cultural exchange | 37 (8%) | 71 (9%) | 0.40 |

| Adventuring | 22 (5%) | 40 (5%) | 0.68 |

| Attending large event | 10 (2%) | 13 (2%) | 0.59 |

| Providing medical care | 17 (4%) | 2 (0.3%) | — |

| Pursued any health information prior to travel | 259 (54%) | 195 (25%) | <0.0001 |

LLMI = low or low-middle income; UMHI = upper-middle or high income; VFR visiting friends and relatives.

The denominator for each category is the number of respondents who answered the given question. Missing data are not represented in the table.

Survey respondents could select more than one purpose of the trip.

Based on two-sided t-tests (continuous variable) or chi-square tests (categorical variable).

Among travelers to LLMI countries, 21% reported verifying that their immunizations were up to date prior to departure, and 36% reported carrying a prescription medication for travelers’ diarrhea. A total of 364 travelers to LLMI countries were visiting countries that included areas endemic for malaria; 20% of these individuals reported carrying a prescription antimalarial drug with them.

By multivariate analysis, several factors were associated with failing to pursue health information among travelers to LLMI countries (Table 2). Being foreign-born, traveling alone, traveling for less than 14 days, and traveling for vacation each predicted higher odds of not pursuing health information, after controlling for other variables. There was a trend toward VFR travel being associated with failure to pursue health information.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with not pursuing health information among travelers to LLMI countries

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.39 |

| Gender (male) | 1.40 (0.91–2.14) | 0.12 |

| Foreign-born | 2.29 (1.25–4.21) | <0.01 |

| Traveling alone | 1.91 (1.17–3.11) | 0.01 |

| Duration of travel <14 d | 3.14 (1.98–4.98) | <0.0001 |

| Purpose of trip | ||

| Vacation | 2.19 (1.23–3.91) | <0.01 |

| VFR | 2.04 (0.94–4.42) | 0.07 |

| Business | 1.05 (0.53–2.06) | 0.89 |

| Volunteer work | 0.19 (0.07–0.48) | <0.001 |

| Education/cultural exchange | 0.61 (0.27–1.39) | 0.24 |

| Adventuring | 0.51 (0.20–1.27) | 0.15 |

VFR = visiting friends and relatives.

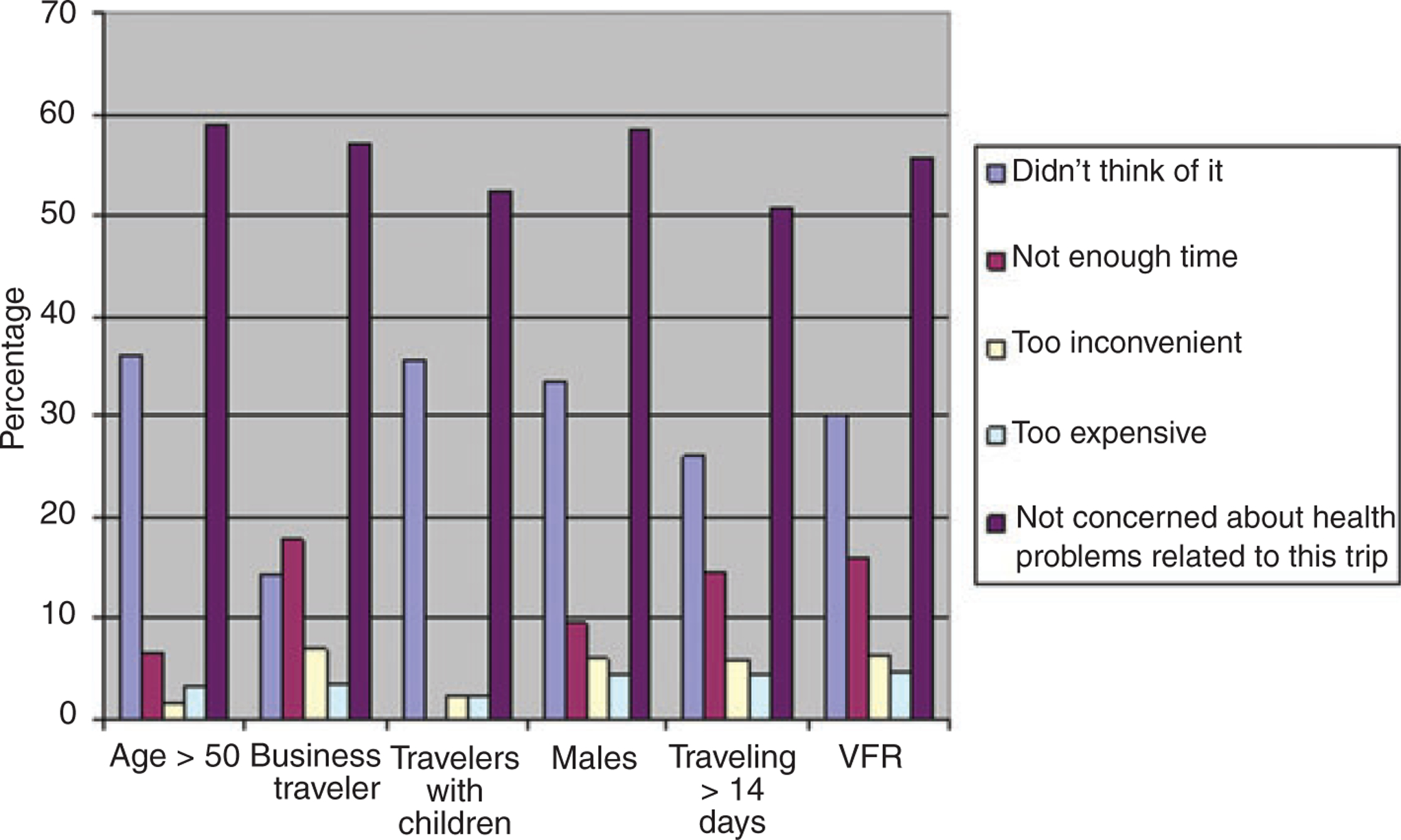

We questioned survey respondents on specific reasons that might have prevented them from pursuing health information prior to their trip. Among all groups, the most commonly cited reason for not pursuing health information was a lack of concern about health problems related to the trip (Figure 1). Survey respondents also commonly reported that they did not consider health problems related to the trip. Business travelers more frequently reported having insufficient time to pursue health information prior to departure than did other classes of travelers. Of note, cost was rarely cited as a barrier to pursuing health information.

Figure 1.

Reasons for not pursuing health information, by type of traveler.

Table 3 shows the sources of health information used by the 259 travelers to LLMI countries who sought medical advice prior to their trip. Overall, the internet was the most common source of health information among survey respondents. Twenty percent of travelers to LLMI countries who sought medical advice specifically reported visiting the CDC Travelers’ Health website (www.cdc.gov/travel); this represents only 11% of all travelers to LLMI countries. More than a third of travelers to LLMI countries (38%) who sought health information obtained it from a primary care practitioner. Of note, VFR travelers who sought medical advice were particularly likely to have obtained health information from a primary care practitioner (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sources of health information among travelers to LLMI countries who pursued health information prior to departure*

| Source | All respondents (n = 259) |

VFR (n = 35) |

Non-VFR (n = 224) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet | 110 (43%) | 11 (31%) | 99 (44%) |

| Primary care practitioner† | 98 (38%) | 20 (57%) | 78 (35%) |

| Travel medicine specialist | 77 (30%) | 1 (3%) | 76 (34%) |

| CDC website | 53 (20%) | 6 (17%) | 47 (21%) |

| Travel book | 26 (10%) | 2 (6%) | 24 (11%) |

| Travel agent/trip organizer | 24 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 23 (10%) |

| Employer | 7 (3%) | 0 | 7 (3%) |

LLMI = low or low-middle income; VFR = visiting friends and relatives.

Survey respondents could select more than one source of health information.

p < 0.05 for comparison between VFR and other travelers.

Discussion

Approximately 80 million people from industrialized nations travel to the developing world each year.5 This travel exposes travelers to preventable health risks that are unique to their destination country and may also pose a risk of importing travel-related diseases to the local population in their home country. In recent decades, travel medicine has grown into a well-developed subspecialty of medicine, with dedicated publications and professional societies. CDC has also focused education efforts on travelers and provides a comprehensive website devoted to travelers’ health (www.cdc.gov/travel). Nevertheless, many travelers do not access health resources prior to departure.6,7 In this study, we surveyed 1,254 international travelers departing from a major US airport, to identify barriers to the pursuit of health information and to understand which, if any, sources of health information were being utilized by travelers to high-risk countries.

Fifty-four percent of survey respondents traveling to LLMI countries reported pursuing health information of any type prior to their trip. This finding is similar to that of a smaller study (n = 404) of US travelers to high-risk destinations departing from John F. Kennedy International Airport, in which 36% reported seeking health advice.8 Also consistent with previous reports, we found that travelers to LLMI countries were more likely to be foreign-born and were more commonly traveling to visit family. Many of these individuals met the CDC definition of VFR travelers—a group in whom a higher risk of travel-associated infectious diseases has been established.9

A number of factors—including foreign birth, traveling alone, traveling for less than 14 days, and traveling for vacation—independently predicted a lower likelihood of pursuing health information prior to departure. Most commonly, travelers reported a lack of concern about health issues as the primary reason that they did not pursue health information prior to their trip. These findings underscore that efforts are needed to heighten the awareness of the risk associated with travel to LLMI countries.

Among travelers to LLMI countries who sought health advice prior to departure, we found the internet to be the most common source of information. However, only a small proportion (11%) of all travelers to LLMI countries visited the CDC Travelers’ Health website. Primary care practitioners were another common source of health information among travelers to LLMI countries, and VFR travelers were particularly likely to have pursued health information from a primary care practitioner. Less than a third of travelers to LLMI countries who pursued health information visited a travel medicine specialist, and among VFR travelers, this number was only 3%.

Boston Logan International Airport is one of the United States’ largest airports in terms of passenger volume and flight movements,10 and travelers departing from Boston Logan International Airport are likely similar to those departing from other major hubs in the United States. Nevertheless, an important limitation of our study was its restriction to a single US airport. Due to the travel patterns from Boston Logan International Airport, few survey respondents were directly traveling to Southeast Asia or sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, although our survey was conducted over more than 7 months, the sample size for any given destination was small and precluded any analysis by geographic destination or country of birth. Survey data from other points of departure in the United States would be useful for gathering information on a broader range of travelers and for identifying any characteristics unique to travelers to specific destinations.

Our results suggest a number of interventions that might be productive in improving the health knowledge of travelers to LLMI countries. In particular, we found the internet to be a key source of health information for travelers to LLMI countries. Given this finding, focusing education interventions at the time of online ticket purchase or through popular websites for travelers might be productive. Linking directly from such sites to the CDC Travelers’ Health website may be a useful tactic, as many survey respondents did not use this resource. Providing web-based material in languages other than English may be useful for targeting foreign-born travelers. Many survey respondents, particularly foreign-born individuals, reported obtaining health information from primary care practitioners; further information about the knowledge and practices of primary care practitioners with regard to travel medicine is needed to understand and optimize the advice that is provided in a generalist setting. Finally, campaigns focused on airports or other common departure venues could improve awareness prior to future trips.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U19CI000514). We thank the staff of Boston Logan International Airport, particularly Chief Robert Donahue, Robert Callahan, Catherine Obert, Brad Martin, David Ishihara, and Dr James Watkins, CDC quarantine officer, for their assistance with this project. We also thank Jana Eisenstein, Jennifer Kendall, Robert Citorik, Erica Sennott, and Richelle Charles for their assistance with administering the airport surveys. We thank Ricky Morse and Peter Lazar for their assistance with data management. We are grateful to Dr Emilia Koumans for a critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors state they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Khan K, Arino J, Hu W, et al. Spread of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus via global airline transportation. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris JS, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004; 10:S88–S97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Development Report 2009: reshaping economic geography. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2009. Available at: http://econ.worldbank.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health information for international travel 2010. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LH, Wilson ME. The role of the traveler in emerging infections and magnitude of travel. Med Clin North Am 2008; 92:1409–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilder-Smith A, Khairullah NS, Song JH, et al. Travel health knowledge, attitude and practices among Australasian travelers. J Trav Med 2004; 11:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Herck K, Van Damme P, Castelli F, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices in travel-related infectious diseases: the European airport survey. J Trav Med 2004; 11:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamer DH, Connor BA. Travel health knowledge, attitude and practices among United States travelers. J Trav Med 2004; 11:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angell SY, Cetron MS. Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACI Airports Economic Survey 2009. Geneva: Airports Council International, 2009. [Google Scholar]