Abstract

Background:

Clinical trials have generally showed a neutral effect of blood pressure (BP) reduction on clinical outcomes among acute ischemic stroke patients. We conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis to assess whether disease severity modifies the effect of early antihypertensive treatment on death and disability among patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Methods:

In the China Antihypertensive Trial in Acute Ischemic Stroke, 4,071 patients with acute ischemic stroke and elevated BP were randomly assigned to receive antihypertensive treatment or to discontinue all hypertension medications within 48 h of symptom onset. The primary outcome was a combination of death and major disability at 14 days or hospital discharge. In this subgroup analysis, participants were categorized into 3 groups according to their baseline NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores (0–4, 5–15, or ≥ 16).

Results:

At 24 h after randomization, mean systolic BP differences (95% CIs) were −8.5 (−10.0 to −7.1), −9.8 (−11.4 to −8.3), and −9.1 (−14.4 to −3.8) mm Hg between the treatment and control groups (all p values <0.001) for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively. At day 7 after randomization, the corresponding mean systolic BP differences were −9.3 (−10.5 to −8.2), −9.1 (−10.3 to −7.8), and −10.1 (−15.1 to −5.1) mm Hg between the treatment and control groups (all p values <0.001). The primary outcome was not significantly different between the treatment and control groups at day 14 or hospital discharge among all NIHSS subgroups (p value for homogeneity = 0.66). ORs (95% CI) associated with treatment were 1.14 (0.87–1.49, p = 0.33), 1.04 (0.86–1.25, p = 0.70), and 0.67 (0.18–2.44, p = 0.54) for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively. The composite outcome of death and major disability at 3-month follow-up did not differ between the 2 comparison groups for all NIHSS subgroups. In addition, vascular events and recurrent stroke were not significantly different between the 2 comparison groups at the 3-month follow-up visit among all NIHSS subgroups except that there was a suggestive risk reduction for recurrent stroke among those with an NIHSS score of 5–15 (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.20–0.99, p = 0.05).

Conclusion:

Early BP reduction with antihypertensive medications did not reduce or increase the risk of death, major disabilities, recurrent instances of stroke, and vascular events in acute ischemic stroke patients with a variety of disease severities.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Antihypertensive treatment, Disability, Mortality, Stroke severity

Elevated blood pressure (BP) is common in the acute phase of ischemic stroke, occurring in about 75% of all patients [1, 2]. The early BP increase following ischemic stroke often reflects uncontrolled or undiagnosed chronic hypertension. However, an early hypertensive response to physical and psychological stresses from brain ischemia is an important contributing factor for elevated BP in acute ischemic stroke [3, 4]. It has been suggested that dynamic cerebral autoregulation is impaired in the affected hemisphere after ischemic stroke, which makes early BP management more challenging [4, 5]. Several clinical trials have tested the effects of individual drug or management strategies of BP lowering on adverse clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke and showed inconsistent results [6–8]. These trials have mostly been conducted in patients with a mild-to-moderate acute ischemic stroke. Overall, they indicated that BP lowering had a neutral effect on death or dependency [9].

Observational clinical studies reported that stroke severity measured by the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was associated with elevated BP during the acute phase, and predicted poor clinical outcomes of ischemic stroke [10–12]. In a subgroup analysis of the Scandinavian Candesartan Acute Stroke Trial, there was a significant trend toward a better effect of candesartan on the functional outcome in patients with larger infarcts (total anterior circulation or partial anterior circulation) than in patients with smaller infarcts (lacunar infarction) [13]. In contrast, there was a trend suggesting a beneficial effect of antihypertensive treatment in lacunar stroke and a detrimental effect in embolic stroke in the China Antihypertensive Trial in Acute Ischemic Stroke (CATIS) [8]. Since stroke severity is highly correlated with stroke subtype, these data provided conflicting information on the modifier effect of disease severity on the effect of early BP lowering on clinical outcomes among patients with acute ischemic stroke. CATIS was a multicenter randomized controlled trial designed to test the effect of BP reduction within the first 48 h after the onset of an acute ischemic stroke on death and major disability [8]. CATIS provides an opportunity to assess the effect of early antihypertensive treatment on death and major disability among patients with acute ischemic stroke according to disease severity.

Methods

Trial Participants

CATIS was a multicenter, single-blind, blinded end-points randomized clinical trial conducted in 26 hospitals across China from August 2009 to May 2013. The trial design, methods, and main results were published elsewhere [8]. In brief, a total of 4,071 patients aged ≥ 22 who had ischemic stroke confirmed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain within 48 h of symptom onset, and with a systolic BP between 140 and <220 mm Hg were recruited into the study. Patients with a systolic BP ≥ 220 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 120 mm Hg, severe heart failure, acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, atrial fibrillation, aortic dissection, cerebrovascular stenosis, or resistant hypertension; those in a deep coma; and those treated with intravenous thrombolytic therapy were excluded [8].

The study was approved by IRBs at Tulane University in the United States and Soochow University in China, as well as Ethical Committees at the 26 participating hospitals. Written consent was obtained from all study participants. A data and safety monitoring board met at least annually to review the accumulating data for safety and to monitor the trial for either superiority or inferiority of BP reduction on clinical outcomes.

Intervention

Participants were randomly assigned to receive antihypertensive treatment or to control. All home antihypertensive agents were discontinued after randomization. Several antihypertensive medications, including intravenous angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (enalapril, first-line), calcium channel blockers (second-line), and diuretics (third-line), were used individually or in combination in the intervention group to achieve the targeted BP reduction according to a prespecified stepwise treatment algorithm. The antihypertensive treatment aimed at lowering systolic BP by 10–25% within the first 24 h after randomization, achieving a systolic BP <140 mm Hg and diastolic BP <90 mm Hg within 7 days, and maintaining this level of BP control during the remainder of a patient’s hospitalization period. Patients in both groups were prescribed antihypertensive medications at their hospital discharge according to clinical guidelines [14, 15].

Measurements

Demographic characteristics and medical histories were collected at enrollment. Stroke severity was assessed by trained neurologists using NIHSS (scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurologic deficits: 0 = no stroke symptoms; 1–4 = minor stroke; 5–15 = moderate stroke; 16–20 = moderate to severe stroke; and 21–42 = severe stroke) at baseline, 14 days or hospital discharge, and 3 months after treatment [16]. Three BP measurements were conducted by trained nurses at baseline according to a common protocol adapted from procedures recommended by the American Heart Association [17]. BP was measured with the participants in a supine position using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer and 1 of 4 cuff sizes (pediatric, regular adult, large adult, or thigh) based on participants’ arm circumferences. After randomization, 3 BP measurements were obtained every 2 h for the first 24 h, every 4 h during the second and third days, and 3 times a day thereafter until hospital discharge or death.

Outcome Assessment

The primary outcome was a combination of death and major disability, defined as a score of 3–6 on the modified Rankin Scale (scores range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms, 5 indicating severe disability, and 6 indicating death) [18]. Secondary outcomes included an ordered 7-level categorical score of the modified Rankin Scale for neurologic functional status, vascular disease events (e.g. vascular deaths, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and hospitalized and treated peripheral arterial disease), recurrent fatal and nonfatal stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Study outcomes were assessed at 14 days or hospital discharge, whichever came first, and at 3 months by trained neurologists and nurses unaware of treatment assignment. Death certificates were obtained for deceased participants. Hospital data were abstracted for all vascular events. The outcome assessment committee, blinded to treatment assignment, reviewed and adjudicated vascular events based on the criteria established in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) [19].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the intention-to-treat analysis. Participants were divided into 3 subgroups according to baseline stroke severity (NIHSS score of 0–4 (no stroke symptoms or minor stroke), 5–15 (moderate stroke), and ≥ 16 (moderate to severe stroke or severe stroke) [16]. Proportions of primary and secondary outcomes at 14 days or hospital discharge and at 3 months were compared between the antihypertensive treatment and control groups using a χ2 test at a 2-sided a level of 0.05 without correction for multiple comparisons within each subgroup. Univariate logistic regression models were used to estimate ORs and 95% CIs associated with antihypertensive treatment vs. control among each NIHSS subgroup. Additionally, the median and interquartile range (IQR) of modified Rankin Scale scores was calculated, and the difference between antihypertensive treatment and control groups was compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Univariate ordinal logistic regression models were used to estimate the effect of BP reduction on the full range of the modified Rankin Scale. In a sensitivity analysis, baseline NIHSS scores were categorized into quartiles (0–2, 2–4, 5–8, and ≥ 9). Homogeneity of treatment effect on all clinical outcomes in subgroups by baseline stroke severity was assessed by adding an interaction term (subgroup × treatment) in logistic regression models. Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

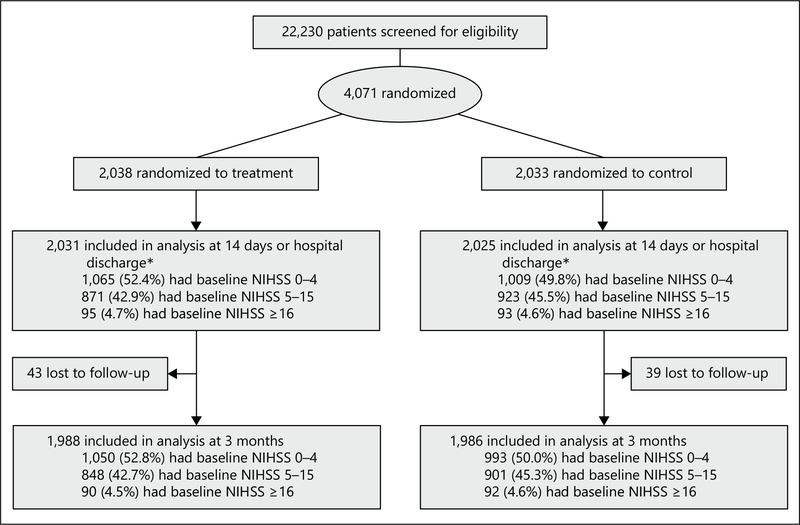

A total of 22,230 patients with acute ischemic stroke were screened from August 2009 to May 2013; of them, 4,071 were eligible and randomly assigned to receive antihypertensive treatment (n = 2,038) or to discontinue all hypertensive medications (n = 2,033). Seven participants in the treatment group and 6 in the control group withdrew from the trial during hospitalization. In addition, 43 participants in treatment and 40 in control groups were lost to follow-up at 3 months (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study participant flowchart. * Seven participants in the antihypertensive treatment group and 8 in the control group had missing data on the baseline NIHSS score.

At entry, 2,074 participants had a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4 (1,065 in intervention and 1,009 in control), 1,794 had a score of 5–15 (871 in intervention and 923 in control), and 188 had a score of ≥ 16 points (95 in intervention and 93 in control). Baseline characteristics were balanced between antihypertensive treatment and control groups within each NIHSS subgroup (table 1). In addition, co-treatments (antiplatelet, anticoagulation, and dehydration) were not significantly different between antihypertensive treatment and control within each NIHSS subgroup.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trial participants according to baseline NIHSS scores*

| NIHSS score 0–4 |

NIHSS score 5–15 |

NIHSS score ≥16 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment (n = 1,065) |

control (n = 1,009) |

P value |

treatment (n = 871) |

control (n = 923) |

P value |

treatment (n = 95) |

control (n = 93) |

P value |

|

|

| |||||||||

| Male, n (%) | 712 (66.9) | 662 (65.6) | 0.55 | 548 (62.9) | 565 (61.2) | 0.46 | 56 (59.0) | 56 (60.2) | 0.86 |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.0 (10.7) | 60.5 (10.8) | 0.25 | 62.8 (10.8) | 62.9 (10.9) | 0.97 | 66.6 (10.6) | 66.4(11.8) | 0.93 |

| Time from onset to randomization, h, mean ± SD | 16.3 (13.2) | 15.8 (12.9) | 0.41 | 14.6 (12.5) | 14.4(13.2) | 0.77 | 10.5 (11.1) | 9.6 (11.1) | 0.60 |

| Blood pressure at entry, mm Hg, mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Systolic | 165.6 (17.2) | 164.8 (16.5) | 0.27 | 167.9 (17.2) | 166.3 (16.4) | 0.05 | 168.1 (18.1) | 167.9 (18.0) | 0.94 |

| Diastolic | 96.3 (10.7) | 96.3 (11.5) | 0.94 | 97.2 (11.0) | 96.8 (11.2) | 0.43 | 98.7(11.3) | 97.3 (11.7) | 0.41 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 24.9 (3.0) | 25.0 (3.2) | 0.52 | 24.9 (3.1) | 25.0 (3.1) | 0.59 | 24.9 (5.3) | 24.8 (3.3) | 0.79 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 846 (79.4) | 806 (79.9) | 0.80 | 676 (77.6) | 716 (77.6) | 0.98 | 81 (85.3) | 73 (78.5) | 0.23 |

| Use of antihypertensive medications, n (%) | 524 (49.2) | 502 (49.8) | 0.80 | 439 (50.4) | 441 (47.8) | 0.27 | 46 (48.4) | 38 (40.9) | 0.30 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 66 (6.2) | 79 (7.8) | 0.15 | 65 (7.5) | 58 (6.3) | 0.32 | 6 (6.3) | 3 (3.2) | 0.32 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 209 (19.6) | 174 (17.2) | 0.16 | 145 (16.7) | 154(16.7) | 0.98 | 15 (15.8) | 21 (22.6) | 0.24 |

| History of coronary heart disease, n (%) | 102 (9.6) | 116 (11.5) | 0.15 | 90 (10.3) | 97(10.5) | 0.90 | 24 (25.3) | 15 (16.1) | 0.12 |

| Current cigarette smoking, n (%) | 409 (38.4) | 399 (39.5) | 0.59 | 285 (32.7) | 326 (35.3) | 0.25 | 31 (32.6) | 34 (36.6) | 0.57 |

| Current alcohol drinking, n (%) | 353 (33.2) | 351 (34.8) | 0.43 | 241 (27.7) | 258 (28.0) | 0.89 | 20 (21.1) | 30 (32.3) | 0.08 |

| NIHSS score at baseline, median (IQR)* | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 0.67 | 7.0 (6.0–10.0) | 7.0 (6.0–10.0) | 0.63 | 19.0 (17.0–22.0) | 19.0 (17.0–22.0) | 0.82 |

Scores range from 0 (normal neurologic status) to 42 (coma with quadriplegia).

BP Reduction

Mean systolic BP was reduced by 22.4 (12.5%), 22.7 (13.1%), and 19.2 mm Hg (11.1%) in the antihypertensive treatment group, and 12.8 (7.3%), 12.9 (7.3%), and 10.0 mm Hg (5.5%) in the control group within 24 h after randomization for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively (table 2). The corresponding mean systolic BP differences were –8.5, –9.8, and –9.1 mm Hg between the treatment and control groups (all p < 0.001). The mean systolic BP differences between the treatment and control groups were –9.3, –9.1, and –10.1 mm Hg at day 7 after randomization (all p < 0.001), and –8.9 (p < 0.001), –8.6 (p < 0.001) and –4.6 (p = 0.19) mm Hg at day 14 after randomization for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively.

Table 2.

Blood pressure reduction after randomization at 14 days or hospital discharge according to baseline NIHSS scores

| NIHSS score 0–4 |

NIHSS score 5–15 |

NIHSS score ≥16 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | control | difference (95% Cl) | p value | treatment | control | difference (95% Cl) | p value | treatment | control | difference (95% Cl) | p value | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Blood pressure at 24 h after randomization, mm Hg, mean ± SD | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | 144.2 (15.2) | 151.9 (15.5) | −7.7 (−9.0 to −6.4) | <0.001 | 145.1 (14.6) | 153.4(15.8) | −8.3 (−9.8 to −6.9) | <0.001 | 147.6 (15.8) | 157.5 (19.7) | −9.9 (−15.1 to −4.6) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 85.6 (8.9) | 89.7(9.9) | −4.1 (−5.0 to −3.3) | <0.001 | 86.0 (8.7) | 89.4 (9.4) | −3.4 (−4.3 to −2.6) | <0.001 | 87.7(9.3) | 90.5 (9.9) | −2.8 (−5.6 to 0.04) | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Absolute blood pressure changes from baseline to 24 h after randomization, mm Hg, mean ± SD | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | −22.4(15.6) | −12.8 (17.4) | −8.5 (−10.0 to −7.1) | <0.001 | −22.7(16.2) | −12.9 (17.0) | −9.8 (−11.4 to −8.3) | <0.001 | −19.2 (15.6) | −10.0 (20.1) | −9.1 (−14.4 to −3.8) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | −10.7(10.4) | −6.6 (11.1) | −4.2 (−5.1 to −3.3) | <0.001 | −11.2 (10.6) | −7.3 (10.9) | −3.9 (−4.9 to −2.9) | <0.001 | −10.7 (11.0) | −6.4 (12.1) | −4.3 (−7.7 to −0.9) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Proportional blood pressure changes from baseline to 24 h after randomization, %, mean ± SD | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | −12.5 (8.6) | −7.3 (9.8) | −5.2 (−6.0 to −4.4) | <0.001 | −13.1 (8.8) | −7.3 (9.6) | −5.8 (−6.7 to −4.9) | <0.001 | −11.1 (8.8) | −5.5 (11.4) | −5.6 (−8.6 to −2.6) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | −10.5 (10.0) | −6.0 (11.2) | −4.5 (−5.4 to −3.6) | <0.001 | −10.9 (10.1) | −6.8 (10.9) | −4.1 (−5.1 to −3.1) | <0.001 | −10.2 (10.5) | −5.8 (12.1) | −4.4 (−7.8 to −1.1) | 0.009 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Blood pressure at day 7 after randomization, mm Hg, mean ± SD | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | 137.1 (11.6) | 146.4(13.3) | −9.3 (−10.5 to −8.2) | <0.001 | 137.4 (11.7) | 146.5 (13.8) | −9.1 (−10.3 to −7.8) | <0.001 | 138.5 (14.5) | 148.6 (15.1) | −10.1 (−15.1 to −5.1) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 82.5 (7.2) | 86.6 (8.4) | −4.1 (−4.8 to −3.3) | <0.001 | 82.1 (7.1) | 86.1 (7.9) | −4.0 (−4.8 to −3.3) | <0.001 | 83.3 (8.1) | 87.2 (7.7) | −3.9 (−6.6 to−1.3) | 0.004 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Blood pressure at day 14 after randomization, mm Hg, mean ± SD | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | 135.2 (10.2) | 144.1 (14.4) | −8.9 (−10.7 to −7.1) | <0.001 | 135.0 (10.2) | 143.6 (13.5) | −8.6 (−10.3 to −7.0) | <0.001 | 136.6 (15.1) | 141.2 (15.7) | −4.6 (−11.5 to −2.3) | 0.19 |

| Diastolic | 81.6 (6.4) | 85.3 (8.8) | −3.7 (−4.8 to −2.6) | <0.001 | 81.2 (8.2) | 85.4(7.8) | −4.1 (−5.2 to −3.1) | <0.001 | 82.0 (7.2) | 85.1 (8.7) | −3.1 (−6.7 to −0.5) | 0.09 |

Clinical Outcomes at 14 Days or Hospital Discharge

At 14 days or hospital discharge, the primary outcome was not significantly different between the treatment and control groups among all NIHSS subgroups (p value for homogeneity = 0.66). ORs (95% CI) associated with treatment were 1.14 (0.87–1.49, p = 0.33), 1.04 (0.86–1.25, p = 0.70), and 0.67 (0.18–2.44, p = 0.54) for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively (table 3). Likewise, the secondary outcomes of modified Rankin Scale scores and death rate were not significantly different between the treatment and control groups within each NIHSS subgroup. In addition, ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that antihypertensive treatment was not associated with the odds of a higher modified Rankin Scale score among all 3 NIHSS subgroups.

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes at 14 days or hospital discharge according to baseline NIHSS scores

| Outcome variables | NIHSS score 0–4 |

NIHSS score 5–15 |

NIHSS score ≥16 |

p value for homogeneity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment (n = 1,065) |

control (n = 1,009) |

OR (95% CI) |

p value | treatment (n = 871) |

control (n = 923) |

OR (95% CI) |

p value | treament (n = 95) |

control (n = 93) |

OR (95% CI) |

p value | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Primary outcome Death or major disability*, n (%) | 134 (12.6) | 113 (11.2) | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 0.33 | 460 (52.8) | 479 (51.9) | 1.04 (0.86–1.25) | 0.70 | 89 (93.7) | 89 (95.7) | 0.67 (0.18–2.44) | 0.54 | 0.66 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Secondary outcomes Score on modified | |||||||||||||

| Rankin Scale†, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.95 | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 0.43 | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 0.78 | 0.83 | |||

| Participants, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 (no symptoms) | 172 (16.2) | 132 (13.1) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18)* | 0.95 | 32 (3.7) | 21 (2.3) | 0.94 (0.79–1.10)‡ | 0.43 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.93 (0.55–1.57)‡ | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| 1 (no significant disability despite symptoms) | 527 (49.5) | 550 (54.5) | 124 (14.2) | 151 (16.4) | 2(2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||||||

| 2 (slight disability) | 232 (21.8) | 214 (21.2) | 255 (29.3) | 272 (29.5) | 4 (4.2) | 4 (4.3) | |||||||

| 3 (moderate disability) | 81 (7.6) | 66 (6.5) | 205 (23.5) | 225 (24.4) | 6 (6.3) | 6 (6.5) | |||||||

| 4 (moderately severe disability) | 41 (3.9) | 41 (4.1) | 188 (21.6) | 208 (22.5) | 29 (30.5) | 33 (35.5) | |||||||

| 5 (severe disability) | 7 (0.7) | 3 (0.3) | 62 (7.1) | 37 (4.0) | 39 (41.1) | 37 (39.8) | |||||||

| 6 (dead) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.6) | 9(1.0) | 15 (15.8) | 13 (14.0) | |||||||

| Death, n (%) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 1.58 (0.38–6.64) | 0.53 | 5 (0.6) | 9(1.0) | 0.59 (0.20–1.76) | 0.34 | 15 (15.8) | 13 (14.0) | 1.15 (0.52–2.58) | 0.73 | 0.49 |

| Duration of initial hospitalization, median (IQR), days | 12.0 (9.0–14.0) | 12.0 (9.0–14.0) | 0.46 | 13.0 (9.0–14.0) | 13.0 (9.0–14.0) | 0.14 | 13.0 (5.0–14.0) | 13.0 (7.0–15.0) | 0.47 | 0.42 | |||

Modified Rankin Score of 3 or greater.

Scores on the modified rankin scale, for which a score of 0 indicates no symptoms, a score of 5 indicates severe disability, and a score of 6 indicates death.

Odds of a 1-unit higher modified Rankin score.

Clinical Outcomes at 3 Months

At 3 months, mean systolic BP differences between treatment and control were –3.5 (p < 0.001), –2.0 (p < 0.001) and –5.1 mm Hg (p = 0.06) for patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16, respectively (table 4). The composite outcome of death or major disability, the median modified Rankin Scale score, death, vascular events, and the combination of vascular events and death were all not significantly different between the treatment and control groups within each NIHSS subgroup (all p > 0.05). For patients with a baseline NIHSS score of 0–4 and ≥ 16 points, the risk of recurrent stroke was not significantly different between the treatment and control groups; for those with a baseline NIHSS score of 5–15 points, there was a borderline significant reduction in recurrent stroke in the antihypertensive treatment group (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.20–0.99; p = 0.05). However, the treatment effects were not statistically different across the 3 NIHSS subgroups (p for interaction = 0.38).

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes at 3-month post-treatment follow-up visit according to baseline NIHSS scores

| NIHSS score 0–4 |

NIHSS score 5–15 |

NIHSS score ≥16 |

p value for homogeneity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment (n = 1,050) |

control (n = 993) |

blood pressure difference or OR (95% Cl) | p value |

treatment (n = 848) |

control (n = 901) |

blood pressure difference or OR (95% Cl) | p value |

treatment (n = 90) |

control (n = 92) |

blood pressure difference or OR (95% Cl) | p value |

||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Blood pressure at 3 months after randomization, mm Hg, mean ± SD | |||||||||||||

| Systolic | 138.5 (11.0) | 142.0 (12.6) | −3.5 (−4.5 to −2.4) | <0.001 | 140.2 (12.3) | 142.3 (11.9) | −2.0 (−3.2 to −0.9) | <0.001 | 139.7 (13.3) | 144.8 (17.4) | −5.1 (−10.5 to 0.3) | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Diastolic | 85.5 (7.5) | 87.2 (7.9) | −1.7 (−2.4 to −1.0) | <0.001 | 86.5 (8.4) | 87.5 (8.0) | −1.0 (−1.8 to −0.2) | 0.01 | 86.6 (7.2) | 88.4 (9.3) | −1.8 (−4.7 to 1.1) | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| Use of antihypertensive | |||||||||||||

| medication, n (%) | 882 (84.0) | 757 (76.2) | 1.64 (1.31 to 2.04) | <0.001 | 719 (84.8) | 663 (73.6) | 2.00 (1.58 to 2.54) | <0.001 | 66 (73.3) | 66 (71.7) | 1.08 (0.57 to 2.08) | 0.81 | 0.16 |

| Death or major | |||||||||||||

| disability, n (%) | 89 (8.5) | 100 (10.1) | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.12) | 0.21 | 335 (39.5) | 320 (35.5) | 1.19(0.98 to 1.44) | 0.09 | 76 (84.4) | 82 (89.1) | 0.66 (0.28 to 1.58) | 0.35 | 0.08 |

| Score on modified | |||||||||||||

| Rankin | |||||||||||||

| Scale†, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.85 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.36 | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 0.83 | 0.73 | |||

| Participants, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 (no symptoms) | 305 (29.1) | 278 (28.0) | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.19)* | 0.85 | 71 (8.4) | 62 (6.9) | 0.93 (0.78 to 1.09)‡ | 0.36 | 1(1.1) | 1(1.1) | 0.94 (0.56 to 1.58)‡ | 0.83 | 0.73 |

| 1 (no significant disability despite symptoms) | 457 (43.5) | 453 (45.6) | 204 (24.1) | 233 (25.9) | 5 (5.6) | 3 (3.3) | |||||||

| 2 (slight disability) | 199 (19.0) | 162 (16.3) | 238 (28.1) | 286 (31.7) | 8 (8.9) | 6 (6.5) | |||||||

| 3 (moderate disability) | 52 (5.0) | 68 (6.9) | 184 (21.7) | 182 (20.2) | 17 (18.9) | 15 (16.3) | |||||||

| 4 (moderately severe disability) | 19 (1.8) | 18 (1.8) | 101 (11.9) | 83 (9.2) | 16 (17.8) | 29 (31.5) | |||||||

| 5 (severe disability) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.6) | 27 (3.2) | 31 (3.4) | 14 (15.6) | 16 (17.4) | |||||||

| 6 (dead) | 16 (1.5) | 8 (0.8) | 23 (2.7) | 24 (2.7) | 29 (32.2) | 22 (23.9) | |||||||

| Death, n (%) | 16 (1.5) | 8 (0.8) | 1.91 (0.81 to 4.47) | 0.14 | 23 (2.7) | 24 (2.7) | 1.02 (0.57 to 1.82) | 0.95 | 29 (32.2) | 22 (23.9) | 1.51 (0.79 to 2.90) | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| Recurrent stroke, n (%) | 16 (1.5) | 20 (2.0) | 0.75 (0.39 to 1.46) | 0.40 | 9(1.1) | 21 (2.4) | 0.45 (0.20 to 0.99) | 0.05 | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.4) | 1.56 (0.25 to 9.58) | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| Vascular events, n (%)†† | 22 (2.1) | 23 (2.3) | 0.90 (0.50 to 1.63) | 0.74 | 15 (1.8) | 28 (3.1) | 0.56 (0.30 to 1.06) | 0.07 | 11 (13.6) | 8 (9.6) | 1.47 (0.56 to 3.88) | 0.43 | 0.23 |

| Death or vascular events, n (%) | 31 (3.0) | 28 (2.8) | 1.05 (0.62 to 1.76) | 0.86 | 31 (3.7) | 43 (4.8) | 0.76 (0.47 to 1.21) | 0.25 | 30 (33.3) | 23 (25.0) | 1.50 (0.79 to 2.86) | 0.22 | 0.24 |

Modified Rankin Score of 3 or greater.

Scores on the modified Rankin Scale, for which a score of 0 indicates no symptoms, a score of 5 indicates severe disability, and a score of 6 indicates death.

Odds of a 1-unit higher modified Rankin Score.

Includes vascular deaths, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, hospitalized and treated angina, hospitalized and treated congestive heart failure, and hospitalized and treated peripheral arterial disease.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using the quartiles of baseline NIHSS scores (0–2, 3–4, 5–8, ≥ 9) as cut-points. The results of the sensitivity analysis were consistent with those of the main analysis (online suppl. tables 1 and 2, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000444722). The primary outcome of death and major disability at day 14 or hospital discharge was not significantly different between the treatment and control groups among all NIHSS subgroups (p value for homogeneity = 0.85). Likewise, the composite outcome of death and major disability at 3-month follow-up did not differ between the 2 comparison groups for all NIHSS subgroups (p value for homogeneity = 0.43).

Discussion

This prespecified subgroup analysis of the CATIS trial found that the primary outcome of death or major disability was not different at 14 days or hospital discharge and at 3-month follow-up between the antihypertensive treatment group and the control group among acute ischemic stroke patients with various disease severities (NIHSS score of 0–4, 5–15, and ≥ 16) despite a significant difference in BP reduction between the 2 comparison groups. Median modified Rankin Scale scores were not significantly different between the treatment and control groups at 14 days or discharge and at 3-month follow-up across NIHSS subgroups. Furthermore, rates of vascular events, recurrent stroke, and all-cause mortality were not significantly different between the 2 comparison groups at the 3-month follow-up visit among all NIHSS subgroups except that there was a suggestive risk reduction for recurrent stroke among those with an NIHSS of 5–15. These results indicate that there is a neutral effect of antihypertensive treatment on death and major disability, recurrent stroke, and other clinical outcomes among acute ischemic stroke patients, which is independent of a patient’s disease severity.

The potential effect modification of stroke severity on BP reduction and clinical outcomes has not been well studied among patients with acute ischemic stroke. It was suggested that serious stroke might involve more transient or permanent damage to the areas involved in the brain regulation of cardiovascular functioning compared to mild stroke [4, 12]. Furthermore, autoregulation might also be more likely to be impaired in patients with severe stroke compared to mild stroke in regions surrounding an acute lesion [4, 5]. Because of these reasons, it was conventionally believed that BP lowering might not be safe among patients with severe acute ischemic stroke [14, 15]. However, our study indicated that antihypertensive treatment did not increase adverse clinical outcomes among patients with severe acute ischemic stroke.

Several randomized trials have tested the effects of BP reduction on clinical outcomes in acute stroke patients with mild to moderate disease severities (median NIHSS scores ranging from 4 to 11) [7, 20, 21]. In the Controlling Hypertension and Hypotension Immediately Post-Stroke (CHHIPS) trial, 179 acute stroke patients with a median NIHSS score of 9 (IQR 5–16) were randomly assigned to receive labetalol (n = 58), lisinopril (n = 58), or placebo (n = 63) for 2 weeks. The primary outcome of death or dependency at 2 weeks was not significantly different among groups [20]. In the Continue or Stop Post-Stroke Antihypertensives Collaborative Study (COSSACS), 763 stroke patients with a median baseline NIHSS score of 4 (IQR 3–8) were randomly assigned to continue (n = 379) or stop (n = 384) pre-existing antihypertensive agents. The results indicated that continuation of antihypertensive drugs did not reduce 2-week death or dependency, cardiovascular event rate, or mortality at 6 months [21]. In the Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke (ENOS) trial, a subgroup of 2,097 patients with acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke and a mean baseline NIHSS score of 11 (SD 6) were randomly assigned to continue (n = 1,053) or stop (n = 1,044) taking their antihypertensive drugs before their stroke. The primary outcome, modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days after randomization, did not differ in the 2 comparison groups [7]. Results from these studies and the CATIS trial primary analysis indicated that early antihypertensive treatment did not reduce or increase adverse clinical outcomes in patients with acute stroke. Our analysis brought to light the new information that the neutral effect of antihypertensive treatment did not significantly vary by stroke severity.

As a subgroup analysis of a clinical trial, there were some inherent limitations in our study, such as multiple comparisons, loss of statistical power, and difficulty in interpretation [22]. Therefore, our study findings cannot provide a definite answer to guide clinical patient care. In addition, there are several limitations specifically related to this study. First, acute stroke patients with BP of 220/120 mm Hg or greater were excluded because the current guidelines recommend antihypertensive treatment in such patients [14, 15]. Patients with intravenous thrombolytic therapy were also excluded because of a different requirement for BP reduction [15]. Thus, our study results might not be applicable to those patients. Second, the sample size for patients with an NIHSS score of ≥ 16 was very small in our study, and small effects of BP reduction therefore cannot be ruled out in this group. However, there was no evidence of heterogeneity in BP-lowering effects by stroke severity in our study. Third, our trial did not compare the appropriate BP targets, times of starting treatment, and classes of antihypertensive drug for early BP lowering in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Finally, data regarding culprit arterial patency, cerebral blood flow, collateral blood flow, and presence of penumbral tissue were not collected in the CATIS trial. Future trials should collect these data to guide BP management in acute ischemic stroke.

In conclusion, this subgroup analysis of the CATIS trial indicates that early BP reduction with antihypertensive medications did not reduce or increase death, major disability, recurrent stroke, and vascular events in acute ischemic stroke patients with a variety of disease severities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinical staff working in all hospitals that participated in this study for their support and contribution to this project and Miss Katherine Obst for her editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This study is supported by Tulane University and Collins C. Diboll Private Foundation, both in New Orleans, La., USA; Soochow University, a Project of the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81320108026), all in China. Dr. Xiaoqing Bu was supported by a research training grant (D43TW009107) from the NIH Fogarty International Center, Bethesda, Md., USA. We acknowledge that the Changzhou Pharmaceutical Factory provided the study drug (Enalapril) for this trial.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None.

Investigators for the CATIS

Study Steering Committee: Jiang He (Chair), Jing Chen, Weijun Tong, Yonghong Zhang, Tan Xu; Data and Safety Monitoring Board: Paul K. Whelton (Chair), Jose Biller, C. Lillian Yau, Zhenxin Zhang, Xingquan Zhao. Study and Data Coordinating Center: Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and School of Medicine, New Orleans, La., USA: Lydia A. Bazzano, Chung-Shiuan Chen, Jing Chen, L. Lee Hamm, Jiang He, Tanika N. Kelly, Shengxu Li, Sheryl Martin-Schild, Katherine T. Mills, Qi Zhao; School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, China: Xiaoqing Bu, Fanlong Kong, Hongmei Li, Hao Peng, Lingyan Tang, Weijun Tong, Aili Wang, Ke Wang, Jiahui Wu, Juan Xu, Tan Xu, Tian Xu, Mingzhi Zhang, Shaoyan Zhang, Yonghong Zhang; Participating Hospitals: Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Hebei United University, Hebei, China (Dali Wang, Yanbo Peng, Li Zhang, Xiaojing Zhao, Suling Gao, Jiang Zhang); Department of Neurology, Yutian County Hospital, Hebei, China (Changjie Liu, Jinchao Wang, Lingjun Kong, Yanhong Wu, Yanan Cao, Baoli Liu); Department of Neurology, Kerqin District First People’s Hospital of Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, China (Zhong Ju, Bing Zhao, Haiying Liu, Maoli Bu, Yongjiang Li); School of Public Health, Taishan Medical College, Shandong, China (Qunwei Li); Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical College, Jiangsu, China (Deqin Geng, Fangfang Zhu, Junjun Shan, Chao Ren, Anbo Cheng); Department of Neurology, The 88th Hospital of PLA, Shandong, China (Jintao Zhang, Cuiling Zhou, Yulan Zhao, Yujie Bi, Na Zhong); Department of Internal Medicine, Feicheng City People’s Hospital, Shandong, China (Dong Li, Cuilan Liang, Shanliang Qiao, Guansheng Zhang, Wei Wang); Department of Neurology, Tongliao Municipal Hospital, Inner Mongolia, China (Fengshan Zhang, Yanqiu Du, Jianhui Zhang, Shuhua He); Department of Neurology, Siping Central Hospital, Jilin, China (Libing Guo, Qingjuan Du, Chunying Zhang, Wenhui Ma); Department of Cardiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning, China (Yingxian Sun); Department of Neurology, Jilin Central Hospital, Jilin, China (Xuemei Wang, Jiale Liu, Yongshun Wang, Dawei Yin); Department of Neurology, General Hospital of First Automobile Works, Jilin, China (Yong Cui, Jing Tian, Hong Chang, Yonghong Gao); Department of Neurology, Tangshan Worker’s Hospital, Hebei, China (Yongqiu Li, Haifeng Gao, Dongsen Zhang); Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jilin University, Jilin, China (Dihui Ma); Department of Neurology, Dongping County People’s Hospital, Shandong, China (Dongsheng Zhang, Jianjun Cui); Department of Neurology, The Second People’s Hospital of Huaian City, Jiangsu, China (Guang Yang, Liandong Zhao, Jingdong Zheng); Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Chengde Medical College, Hebei, China (Yanjun Gao, Liang Zhao); Department of Neurology, Kailuan General Hospital, Hebei, China (Xiaodong Yuan, Shujuan Wang); Department of Neurology, Anshan Changda Hospital, Liaoning, China (Xiujie Han, Dan Zhou, Yulin Song); Department of Neurology, Wenshang County Chinese Traditional Medicine Hospital, Shandong, China (Mingyu Zhang); Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Heilongjiang, China (Shurong Duan); Department of Neurology, First People’s Hospital of Kezuohouqi, Inner Mongolia, China (Tao Feng); Department of Neurology, Suzhou Kowloon Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Jiangsu, China (Jizhen Li); Department of Neurology, Anshan Hospital of the First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University, Liaoning, China (Suzhen Liu, Likui Hu); Department of Neurology, Anshan Central Hospital, Liaoning, China (Wei Hu); Department of Neurology, Anshan Shuangshan Hospital, Liaoning, China (Chun Nie); Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia National University, Inner Mongolia, China (Nuenjiya Zhao).

References

- 1.Qureshi AI, Ezzeddine MA, Nasar A, Suri MF, Kirmani JF, Hussein HM, Divani AA, Reddi AS: Prevalence of elevated blood pressure in 563,704 adult patients with stroke presenting to the ED in the United States. Am J Emerg Med 2007;25:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Xu J, Zhao X, Wang D, Wang C, Liu L, Wang A, Meng X, Li H, Wang Y: Association of hypertension with stroke recurrence depends on ischemic stroke subtype. Stroke 2013;44:1232–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlberg B, Asplund K, Hägg E: Factors influencing admission blood pressure levels in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 1991;22:527–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qureshi AI: Acute hypertensive response in patients with stroke: pathophysiology and management. Circulation 2008;118:176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen NH, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Reccius A, Masurkar A, Huang A, Marshall RS: Dynamic cerebral autoregulation is transiently impaired for one week after large-vessel acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;39:144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandset EC, Bath PM, Boysen G, Jatuzis D, Kõrv J, Lüders S, Murray GD, Richter PS, Roine RO, Terént A, Thijs V, Berge E; SCAST Study Group: The angiotensin-receptor blocker candesartan for treatment of acute stroke (SCAST): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Lancet 2011;377: 741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ENOS Trial Investigators, Bath PM, Woodhouse L, Scutt P, Krishnan K, Wardlaw JM, Bereczki D, Sprigg N, Berge E, Beridze M, Caso V, Chen C, Christensen H, Collins R, El Etribi A, Laska AC, Lees KR, Ozturk S, Phillips S, Pocock S, de Silva HA, Szatmari S, Utton S: Efficacy of nitric oxide, with or without continuing antihypertensive treatment, for management of high blood pressure in acute stroke (ENOS): a partial-factorial randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385: 617–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Zhang Y, Xu T, Zhao Q, Wang D, Chen CS, Tong W, Liu C, Xu T, Ju Z, Peng Y, Peng H, Li Q, Geng D, Zhang J, Li D, Zhang F, Guo L, Sun Y, Wang X, Cui Y, Li Y, Ma D, Yang G, Gao Y, Yuan X, Bazzano LA, Chen J; CATIS Investigators: Effects of immediate blood pressure reduction on death and major disability in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the CATIS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Li C, Li T, Xiong J, Zhao X: Effects of early hypertension control after ischaemic stroke on the outcome: a meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;40:270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvistad CE, Logallo N, Oygarden H, Thomassen L, Waje-Andreassen U, Naess H: Elevated admission blood pressure and stroke severity in acute ischemic stroke: the Bergen NORSTROKE Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 36:351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong AA, Davis JP, Schluter PJ, Henderson RD, O’Sullivan JD, Read SJ: The time course and determinants of blood pressure within the first 48 h after ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;24:426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manabe Y, Kono S, Tanaka T, Narai H, Omori N: High blood pressure in acute ischemic stroke and clinical outcome. Neurol Int 2009; 1:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandset EC, Jusufovic M, Sandset PM, Bath PM, Berge E; SCAST Study Group: Effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment in different subtypes of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015;46:877–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.China National Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Cerebrovascular Diseases Committee: China National Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Cerebrovascular Diseases. Beijing, People’s Medical Publishing Houses, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, Bruno A, Connors JJ, Demaerschalk BM, Khatri P, McMullan PW Jr, Qureshi AI, Rosenfield K, Scott PA, Summers DR, Wang DZ, Wintermark M, Yonas H; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology: Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:870–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V: Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ: Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the council on high blood pressure research professional and public education subcommittee. Circulation 2005;111:697–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonita R, Beaglehole R: Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke 1988;19:1497–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Manual of Operations. University of Texas Coordinating Center for Clinical Trials website. https://ccct.sph.uth.tmc.edu/allhatoutreach/ (accessed August 8, 2013).

- 20.Potter JF, Robinson TG, Ford GA, Mistri A, James M, Chernova J, Jagger C: Controlling hypertension and hypotension immediately post-stroke (CHHIPS): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson TG, Potter JF, Ford GA, Bulpitt CJ, Chernova J, Jagger C, James MA, Knight J, Markus HS, Mistri AK, Poulter NR; COSSACS Investigators: Effects of antihypertensive treatment after acute stroke in the continue or stop post-stroke antihypertensives collaborative study (COSSACS): a prospective, randomised, open, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM: Statistics in medicine–reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2189–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.