Abstract

Objectives

The present study examines how varying levels of restrictions on the nightlife economy have impacted violent crime during the COVID-19 pandemic and the extent to which the crime preventive side-effects of restrictions are associated with the density of alcohol outlets.

Methods

The Data stems from geocoded locations of violent crimes combined with data on the density of on-premises alcohol outlets and the level of COVID-19 restrictions in Copenhagen, Denmark. We use a negative binomial count model with cluster robust standard error to assess the effect of the interaction between alcohol outlet density and COVID-related restriction levels on the nightlife economy on the frequency of violent crime.

Results

The article reveals how both the level of restrictions on the nightlife economy and the density of alcohol outlets significantly impacted the frequency of violent crime. The regression analysis shows that the effect of restrictions on the nightlife economy depends on the concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets in the area. In areas with a high concentration of outlets, we observe a much higher reduction in crime as consequence of the COVID-19 related restrictions.

Conclusions

The results shows that a more restricted nightlife economy, including earlier closing times, could have a crime preventive effect, especially in areas with a high density of alcohol outlets.

Keywords: Alcohol outlet, COVID-19 restrictions, Violent crime, Routine activity theory

1. Introduction

Several studies suggest a positive correlation between on-premises alcohol outlet concentration and violent crime (e.g., Conrow, Aldstadt, & Mendoza, 2015; Groff & Lockwood, 2014; Wei, Grubesic, & Kang, 2020) and between outlet opening hours and violent crime (e.g., Burton et al., 2017; De Goeij et al., 2015; De Vocht et al., 2017; Kypri, Jones, McElduff, & Barker, 2011; Kypri, McElduff, & Miller, 2014; Rossow & Norström, 2012; Wilkinson, Livingston, & Room, 2016). This suggests a link between the availability of alcohol, level of nightlife activity, and violent crime. Currently, however, our knowledge of the interplay between opening hours and alcohol outlet density is limited. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique opportunity to study this relationship, as the pandemic and associated restrictions represent a natural experiment in which the nightlife activity levels change due to the varying restrictions on bars, restaurants, nightclubs, etc. The central question is, thus, whether restrictions on nightlife establishments will reduce the level of violent crime differently in areas with high alcohol outlet concentrations compared to low-concentration areas. Specifically, the present study investigates the extent to which COVID-19 nightlife restrictions moderate the relationship between alcohol outlet concentration and violent crime. We estimated a negative binomial model to test the effect of both COVID-19 related restrictions and alcohol outlet concentration on the level of violent crime as well as the interaction effect. Our hypothesis is that the different measures implemented to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus (specifically, the restrictions aimed at reducing nightlife activity) will reduce violent crime more in areas with high concentrations of on-premises alcohol outlets. Data on geocoded locations of criminal offences were combined with geocoded data on the concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets.

We contribute to the literature on the criminogenic impact of COVID-19 restrictions and nightlife activity in several ways. First, we use 0.01 km2 grid cells (100 m × 100 m) as our unit of analysis, which is more finely grained than most other analyses. The geographical unit used in most studies is based on census tract data or LSOA (Lower Super Output Area) (Langton, Dixon, & Farrell, 2021a; Lightowlers, Pina-Sánchez, & McLaughlin, 2021). Second, the gradual opening (and lockdown) of Danish society allows distinction to be drawn between different levels of opening-hour restrictions and, thus, different levels of nightlife activity. Third, the examination of the interaction between alcohol outlet density and the level of restrictions enables us to examine the mechanism behind the drop in violent crime during the COVID-19 lockdown. This allows us to move beyond the results found in the existing literature on the overall effect of COVID-19 restrictions on violent crime and to identify more closely how the restrictions disrupt the criminogenic processes.

This study then contributes both to the literature on the criminogenic effect of COVID-19 restrictions and the literature on how nightlife activity (i.e., the impact of the spatial concentration of alcohol outlets and their opening hours) has an impact on violent crime. Several studies have shown a significant drop in violent crime during the pandemic (Langton, Dixon, & Farrell, 2021; Nivette et al., 2021), and numerous authors assume that the drop in crime is related to nocturnal activity and alcohol consumption (Nivette et al., 2021). However, no studies have directly linked the drop in violent crime during the pandemic geographically to places with high concentrations of alcohol outlets and the nightlife economy. Several studies have previously found a robust association between alcohol outlet concentration and violent crime (Conrow et al., 2015; Groff & Lockwood, 2014; Wei et al., 2020). As regards the effect of opening hours, smaller experimental studies have shown an effect of reducing the opening hours of on-premises alcohol outlets in smaller areas; however, no studies have examined the differential effect of nightlife restrictions.

2. Theory

Cohen and Felson's (1979) seminal article, “Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach,” made clear that crime and victimization is closely related to everyday routine activities. This is particular evident in the temporal and spatial distribution of crime, which mirrors the different opportunities for crime in different settings. Theorizing the spatial dimension of routine activity theory, Brantingham and Brantingham (1995) have proposed a framework for understanding the different mechanisms whereby different places can become crime hotspots. They distinguish between places that can be considered crime attractors (i.e., places attracting many motivated offenders) and places that function as crime generators (by attracting many suitable targets). Areas with high concentrations of alcohol outlets have generally been considered crime attractors (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1995, p. 8).

Empirical work has generally found a solid connection between alcohol outlet density and crime, violent crime in particular (e.g., Conrow et al., 2015; Groff & Lockwood, 2014; Wei et al., 2020). Research has also suggested that the association between alcohol outlet density and violent crime is not linear but curvilinear (J-shaped). In other words, the link between alcohol outlet density and violent crime seems strongest in areas with the highest density of on-premises alcohol outlets. This “multiplier effect” suggests a saturation or tipping point, where the normal mechanism that holds violent crime in check breaks down (Gmel, Holmes, & Studer, 2016; Levine, 2017; Livingston, 2008; Pridemore & Grubesic, 2013; Wei et al., 2020). Several explanations for this multiplier effect have been suggested (see, e.g., Levine, 2017, p. 160), where self-selection seems especially important, as areas with very high concentrations of on-premises outlets seem to create a culture of heavy drinking and loud music combined with extensive street activities both inside and outside the establishments, which attracts a certain type of risk-seeking patrons. But not only do areas with high concentrations of on-premises alcohol outlets function as crime attractors, they can also be seen as crime generators in the sense that many people seek out these areas because of their vibrant nightlife and become easy targets as intoxication renders them increasingly vulnerable to violent victimization.

Opportunities and alcohol availability can also be seen as affecting crime in the connection found between on-premises alcohol outlet opening hours and crime. Although there are exceptions (Humphreys & Eisner, 2014), the vast majority of studies examining the crime–opening hours connection have found a significant positive connection (Burton et al., 2017; De Goeij et al., 2015; De Vocht et al., 2017; Kypri, Jones, McElduff and Barker, 2011, Kypri, McElduff and Miller, 2014; Rossow & Norström, 2012; Wilkinson et al., 2016). In a study of the effect of increasing opening hours in Amsterdam, De Goeij et al. (2015) found that increasing openings hour by 1 h increased alcohol-related damage by 34%.

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a major disruption in the daily lives of most people as it led to city-, region-, and country-wide lockdowns. The effect of these lockdowns was most pronounced for those living in the most densely populated cities. While this disruption also affected crime levels, the impact has varied for different crime types and different countries (Ashby, 2020; Campedelli, Favarin, Aziani, & Piquero, 2020). It is beyond the scope of this paper to untangle the underlying reasons for these heterogeneities, but they are likely a consequence of differences in lockdown measures and the general socioeconomic vulnerability of the populations and the different compensation measures introduced in different countries.

Although some research indicates that, on some measures, violence might have increased in the USA during the pandemic (Mohler et al., 2020; Rosenfeld & Lopez, 2020), most research conducted in other countries has shown that the pandemic and accompanying lockdown measures have reduced levels of violence (Andresen & Hodgkinson, 2020; Gerell, Kardell, & Kindgren, 2020; Langton et al., 2021; Payne & Morgan, 2020; Payne, Morgan, & Piquero, 2020). At present, it is not obvious what kind of violence has contributed to this drop, but a British study based on emergency room data, for example, found that the reduced violence was limited to violence outside the home, whereas violence at home did not wane (Shepherd, Moore, Long, Mercer Kollar, & Sumner, 2021). Additionally, although early evidence has suggested that domestic violence might actually have increased during the lockdown (Piquero, Jennings, Jemison, Kaukinen, & Knaul, 2021), other studies have not reached the same conclusion (Lopez & Rosenfeld, 2021; Wang, Fung, & Weatherburn, 2021).

The present study specifically examines the impact of lockdown measures on nightlife-related violence. Based on our theoretical framework, we present the following hypotheses:

-

1)

Tighter restrictions on the nightlife economy due to COVID-19 will reduce the level of police-recorded, violent crime.

-

2)

Higher concentrations of on-premises alcohol outlets will increase violent crime.

-

3)

COVID-19 restrictions on the nightlife economy will reduce violent crime more in areas with high concentrations of on-premises alcohol outlets.

3. The context of the study: Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital of Denmark and has roughly 700,000 inhabitants.1 Denmark is a highly developed, comprehensive welfare state, and Copenhagen is being branded as a dynamic modern city with aspirations to attract tourists to its vibrant cultural life. Compared to other Nordic countries, Denmark has relatively liberal alcohol policy, including lower legal age limits for off-premises alcohol sales (16 years for beer and wine, 18 years for hard liquor), lower taxes on alcoholic beverages, and liberal rules for retail sales (Tingerstedt et al., 2020).

Denmark responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with a relatively rapid lockdown of society but was also quick to reopen parts of society once the rate of infection began to wane. The prompt reopening of society in different phases provides a unique opportunity to examine the impact on violent crime at different levels of restrictions on the nightlife economy.

3.1. Data and methods

The data consists of geocoded locations of reported violent crime. For each violent incident, we have data for its location, as the police record the address of the incident and time of its occurrence. The geocode crime data was aggregated to 10,000 m2 /0.01 km2 grids. Crime incidents were also aggregated in weekly slots. Because we needed to locate violent events precisely in time and space, we only include crime data with precise geographic information (i.e., crime data with complete address information). The data consists of violent crime statistics obtained for the period January 1–October 30 in 2019 and 2020. The unit of the analysis was 0.01 km2 grid cells per week. There are 10,509 grid cells observed, and 88 weekly slots, which yielded 945,810 observations. However, as the geographic location of incidents of crime is tied to an address in the police registration process, we restrict our data set to grid cells within the Copenhagen/Frederiksberg area, wherein is located at least one address according to the national register of addresses to avoid a substantial number of false zero cells. We have also excluded a grid cell where a prison is located. The negative binomial regression analysis is then based on 7469 grid cells in 80 weekly slots. We end up with a data set consisting of 597,520 observations.

3.2. Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is the number of incidents of violent crime per 0.01 km2 per week. The Danish national police supplied us with data covering all of the violent crime reported to the police in the period January–October for both 2019 and 2020. The total number of violent incidents was 2405, and the number of violent incidents/0.01 km2/week ranged from 0 to 33 (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent incident | 597,520 | 0.005 | 0.089 | 0 | 33 |

| Restriction level | |||||

| Few restrictions | 597,520 | 0.025 | 0.156 | 0 | 1 |

| Medium restrictions | 597,520 | 0.163 | 0.369 | 0 | 1 |

| High level of restrictions | 597,520 | 0.075 | 0.263 | 0 | 1 |

| Closed | 597,520 | 0.100 | 0.300 | 0 | 1 |

| Alcohol outlet density | 597,520 | 0.616 | 1.858 | 0 | 36.25 |

| Addresses | 597,520 | 12.352 | 9.260 | 1 | 80.0 |

| Season | |||||

| Quarter 2 | 597,520 | 0.325 | 0.468 | 0 | 1 |

| Quarter 3 | 597,520 | 0.250 | 0.433 | 0 | 1 |

| Quarter 4 | 597,520 | 0.125 | 0.331 | 0 | 1 |

3.3. Independent variable

The main independent variable is the geographically averaged on-premises alcohol outlet density. This data was obtained by combining data from the Alcohol Permission System, which is operated by the national police, and information from the central business register in Denmark. On-premises alcohol outlets are defined as establishments selling alcoholic beverages for consumption onsite (e.g., restaurants, bars, nightclubs). All on-premises alcohol outlets with an address in Copenhagen or Frederiksberg were entered into the data set. Each outlet was geocoded and aggregated to the grid.

As the level of nightlife activity in an area depends not only on the concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets in that particular area but also on the concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets in neighboring areas, we calculate a geographic average for each grid cell that considers the number of outlets in the focal area together with neighboring areas (defined using a queen specification). The weighted average of alcohol outlet density at location i, that is xi, is given by xi + 2*(Σj wijxj), where the weighted sum is over those “neighbors” j that have a nonzero value for element wij in the weight matrix (Ejrnæs, Scherg, Cold, & Staunstrup, 2021).

The weighted average of on-premises alcohol outlet density/0.01 km2 ranges from 0 to 36.25. The second independent variable indicates the level of restrictions on on-premises alcohol outlets. Because the alcohol outlet opening hours vary during the pandemic due to different restrictions on the nightlife economy, we constructed a five-category variable (no extraordinary restrictions, few restrictions on opening hours, medium levels of restrictions, high levels of restrictions on nightlife, and closed nightlife) indicating the level of restrictions on opening hours. The “no restriction” category consists of the weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic without any extraordinary restrictions on opening hours. The opening hours for on-premises alcohol outlets in Denmark are normally decided by local municipal licensing boards, which can permit an establishment to remain open until 5 am. Approximately 20% of on-premises alcohol outlets in Copenhagen are licensed to serve alcoholic beverages until 5 am (Københavns Kommune, 2020). “Few restrictions” covers the weeks where no on-premises alcohol outlet was allowed to be open after 2 am. “Medium restrictions” indicates that no on-premises alcohol outlets were allowed to close later than 12 pm, and “high level of restrictions” covers the weeks where all on-premises alcohol outlets had to close at 10 pm. “Closed” indicates the period during the lockdown in which all on-premises alcohol outlets were closed.

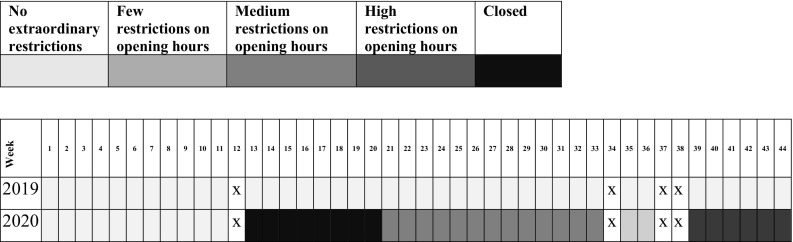

The weeks marked with an “x” are excluded from the analysis, as new restrictions took effect midweek (See Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 restrictions on nighttime economy opening hours.

We also seek to control for the general activity in an area by including a variable measuring the number of addresses in it. Similarly, we seek to control for the effect of seasonality by including a quarter-year variable.

3.4. Statistical model

We estimated a negative binomial regression for police-recorded violent crime. Negative binomial regression was selected due to the count nature of the data on violent crime and the skewed distribution of the dependent variable. Because observation within grid cells is not independent, we use cluster robust standard error. To test how restrictions on the nightlife economy moderate the effects of alcohol outlets on police-recorded violent crime, we include an interaction term. In the regression model we control for number of addresses and seasonal variation in crime. We use the interaction model below to test our main hypothesis.

-

•

Violent incident: the number of police-recorded violent incidents in a grid cell i for week t.

-

•

Few restrictions: dummy variable that 1 equals those weeks where the opening hours for on-premises alcohol outlets are restricted to 2.00 am.

-

•

Medium restrictions: dummy variable that 1 equals weeks where the opening hours are restricted to 12.00 pm.

-

•

High level of restrictions: dummy variable that 1 equals weeks where the opening hours are restricted to 10 pm.

-

•

Outlet density: continuous variable indicating the geographically weight number of on-premises alcohol outlets in the grid cell i.

-

•

Addresses: number of addresses in the grid cell i.

-

•

Quarter2: dummy variable that equals 1 in April, May, and June.

-

•

Quarter3: dummy variable that equals 1 in July, August, and September.

-

•

Quarter4: dummy variable that equals 1 in October.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

Fig. 2 illustrates the time series for incidents of violent crime. The figure compares the development in violent crime in areas without any alcohol outlets (i.e., alcohol outlet density =0) and the number of incidents of violent crime in areas with alcohol outlets (i.e., alcohol outlet density > 0).

Fig. 2.

Development in violent crime (January 2019–October 2020).

The figure reveals two interesting details. Firstly, that in areas without any alcohol outlets, the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions hardly affect the number of incidents of crime. Secondly, we see that the number of violent crime incidents actually drops a few weeks before the COVID-19 restrictions were implemented.2 On average, the number of incidents of crime dropped by approximately 40% after the restrictions were introduced in areas with alcohol outlets.

As part of the descriptive statistics, we did an explorative spatial analysis – specifically a hotspot analysis of violent crime in Copenhagen (search radius 200 m, grid size 10 m and using a quartic kernel). Fig. 3 compares concentrations of violent crime before the COVID-19 pandemic (March–October 2019) and during the pandemic (March 2020–October 2020). The hotspot analysis shows how the level of violent crime dropped in Copenhagen during the pandemic and that the drop seems particular salient in central Copenhagen (See Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hotspot analysis.

4.2. Negative binomial analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the negative binomial regression with clustered standard error. We report the incident rate ratio (IRR), which can be interpreted as the ratio of violent incidents of a category compared with that of the reference group. Incident rates greater than 1 indicate a positive relationship, whereas incident rates lower than 1 indicate a negative relationship.

Table 2.

Explaining violent crime.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref: No restrictions | |||

| Few restrictions | 0.866 | 0.937 | 1.013 |

| Medium restrictions | 0.723⁎⁎⁎ | 0.780⁎⁎⁎ | 0.860 |

| High restrictions | 0.587⁎⁎⁎ | 0.663⁎⁎⁎ | 0.762⁎ |

| Closed | 0.508⁎⁎⁎ | 0.558⁎⁎⁎ | 0.677⁎⁎⁎ |

| Addresses | 1.043⁎⁎⁎ | 1.017⁎⁎⁎ | 1.016⁎⁎⁎ |

| Ref: Quarter1 | . | . | . |

| Quarter2 | 1.228⁎⁎ | 1.228⁎ | 1.230⁎ |

| Quarter3 | 1.127 | 1.114 | 1.118 |

| Quarter4 | 1.166 | 1.106 | 1.105 |

| Outlet density | 1.244⁎⁎⁎ | 1.271⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Interaction effect | |||

| Few restrictions × on-premises alcohol outlet density | 0.951 | ||

| Medium restrictions × on-premises alcohol outlet density | 0.939⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| High level restrictions × on-premises alcohol outlet density | 0.915⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Closed × on-premises alcohol outlet density | 0.872⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| _cons | |||

| Lnalpha | 52.49⁎⁎⁎ | 26.93⁎⁎⁎ | 25.83⁎⁎⁎ |

| N | 597,520 | 597,520 | 597,520 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0154 | 0.0524 | 0.0536 |

⁎p < 0.05, ⁎⁎p < 0.01, ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001.

Model 1 shows that the level of nightlife restrictions has a significant impact on the number of violent incidents. Fig. 4 shows that during the lockdown, when the nightlife establishments were closed, we find the highest drop in violent crime compared to the period before the lockdown. The figure shows that we find a clear negative relationship between the level of restrictions and the number of violent incidents pr. 0.01 km2 grid cells. If we compare the no-restrictions scenario with the lockdown period, we see a (1–0.51 = 0.49) 49% reduction in violent crime. The medium restrictions scenario, where the closing hour for on-premises alcohol outlet was 12 pm, we see a 28% reduction in crime. The results confirm the first hypothesis: that opening-hours restrictions reduce overall violent crime indicents. According to the marginal effect analysis, the violent count decreases by approximately 0.003 during the lockdown (See Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Prediction of violent crime incident at various restrictions level.

Model 2 includes the outlet density variable. The significant positive coefficient indicates a positive association between alcohol outlet density and police-recorded violent incidents. The result is in line with previous studies indicating a robust association between alcohol outlet density and violent incidents. For a 1-unit increase in the outlet density variable, the frequency of violent crime incidents increases by (1–1.24 = 0.24) 24%. We can then confirm the second hypothesis, which states that a greater concentration of alcohol outlets increases the likelihood of violent incidents.

Model 3 adds an interaction term between outlet density and level of restrictions. In this model, we examine the extent to which the effect of COVID-19 restrictions on nightlife is moderated by the density of on-premises alcohol outlets in the area. We find a significant interaction effect, which indicates that COVID-19 restrictions have primarily had an effect on violent crime in areas with a high concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets. The result of the negative binomial regression shows that the effect of nightlife restrictions depends on the concentration of alcohol outlets in the area. This means that the positive associations between alcohol outlets and violent crime weakens when there are restrictions on opening-hours. To illustrate the results, we have calculated the predicted reduction in incidents of crime in areas with different alcohol outlet density levels (See Table 3 ). In areas with one alcohol outlet/0.01 km2, we find a 19% reduction in incidents of violent crime in the medium restrictions scenario compared to “no restrictions.” In areas with 10 alcohol outlets/0.01 km2, we find a 54% reduction in incidents of violent crime.

Table 3.

Crime Reduction.

| 1 Alcohol outlet |

5 Alcohol outlets |

10 Alcohol outlets |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Count | Percent Reduction | Estimated Count | Percent Reduction | Estimated Count | Percent reduction | |

| Ref: No restrictions | 0.0044 | 0.0116 | 0.0388 | |||

| Few restrictions | 0.0043 | 4% | 0.0092 | 21% | 0.0238 | 39% |

| Medium restrictions | 0.0036 | 19% | 0.0073 | 37% | 0.0178 | 54% |

| High restrictions | 0.0031 | 30% | 0.0057 | 51% | 0.0121 | 69% |

| Closed | 0.0026 | 41% | 0.0040 | 66% | 0.0066 | 83% |

Fig. 5 shows how the level of restrictions reduces the strength of the curvilinear association between on-premises alcohol density and incidents of violence. In other words, the COVID-19 nightlife restrictions have a much higher crime preventive effect in areas with high alcohol outlet density.

Fig. 5.

The interaction between alcohol outlets and level of restrictions.

4.3. Robustness check

Several checks were conducted to confirm the robustness of these findings. First, we employed a negative binomial multi-level model in which weeks are nested into grid cells (Supplementary material Table 1). To account for the nested structure in the data, we include a random intercept for grid cells that informs about the variability in violent crime across different grid cells. The results of the multilevel model did not deviate from the results of the negative binomial model with clustered standard error.

Second, the negative binomial regression with clustered standard error was also compared with a linear regression with fixed effects for grid cells (Supplementary material Table 2). The results of the fixed effect regression were consistent with the negative binomial regression results. Third, we also ran a regression with the outlet density variable recoded into three dummy variables indicating different outlet density levels (Supplementary material Table 3). Again, the result does not deviate substantially from the former analysis. We also ran a regression where we excluded one outlier grid cell which had an extraordinary rate of violence on one day in 2019 caused by a political demonstration (Supplementary material Table 4). Again, the results did not deviate substantially. Finally, we also ran a regression with the variable indicating the number of alcohol outlets without the neighborhood effect (spatial smoothening) (Supplementary material Table 5). While the results again did not deviate, the size of the effects was reduced when using the number-of-outlets variable without the neighborhood effect. The robustness check indicates that the neighboring grid cells have a substantial impact on violent crime (which is not surprising given the rather small grid cells).

5. Conclusion

On the one hand, this study sheds some light on the mixed results of previous research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on crime. Our study showed how specifically nightlife-related violent crime was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic because of the restrictions on social activity. We could not see any impact on violence in other settings. Although this finding can hide underlying developments in other types of violence (e.g., workplace violence might have also fallen, while domestic violence might have increased), the results clearly indicate that restrictions on the opening hours of on-premises alcohol outlets were a major reason why violent crime in Copenhagen fell during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the study sheds light on the question about the connection between nightlife related activity, alcohol availability, and violent crime. Our findings show that the concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets increases the level of violent crime. Second, that restrictions on opening hours reduce violent crime. This finding is in line with previous research. However, the most interesting results are that the reductions in violent crime resulting from COVID-19 restrictions were larger in areas with high concentrations of alcohol outlets. This means that the crime preventive effects of restrictions on nightlife opening hours are moderated by the concentration of alcohol outlets. The results are consistent with opportunity theory, according to which restrictions on social activities and interactions reduce criminal opportunity. More specifically, the article supports the alcohol availability thesis, which suggest that greater alcohol availability, both in terms of the concentration of outlets and temporally in terms of opening hours, has a strong impact on violent crime. Secondly, the study indicates that it is especially in the late hours that violent crime occurs in the most active nightlife areas. Our results clearly indicate that limiting late-hours nightlife activity in areas with high concentrations of alcohol outlets will have a significant impact on violent crime in these areas. Crime prevention effects can thus be achieved by either reducing the concentration of alcohol outlets where there is already a high concentration of on-premises alcohol outlets or by reducing the opening hours for the establishments with the longest opening hours. Specifically, in our case, placing restrictions on alcohol outlets in the high-density areas of the city will likely have a significant impact on crime while only affecting a small subset of all on-premises alcohol outlets.

5.1. Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we rely on police-recorded data, which are limited by the considerable number of incidents of crime that go unreported. Our study will likely underestimate the real number of violent incidents. However, the level of police-recorded crime has traditionally been high in Denmark. Secondly, we rely on a time invariant measure of alcohol outlets. The time period is relatively short, however, and the level of compensation was relatively high during the lockdown. There is therefore reason to expect that the geographical distribution of alcohol outlets does not change substantially during the period. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally changed daily routines. We are therefore unable to completely isolate the effect of the specific nightlife restrictions from other social-distancing initiatives. Finally, this study lacks external validity because it only focuses on one city, and it could be highly dependent on specific characteristics of the Danish welfare state and the alcohol licensing policy in Denmark.

Funding

This work was supported by the The Danish Crime Prevention Council.

Acknowledgements

We thank Adam Cold for helping in collecting and cleaning the data and Jan K. Staunstrup for geo-coding the data.

Footnotes

Embedded within the municipality of Copenhagen is the small municipality of Frederiksberg. Although the make-up of Frederiksberg is somewhat different from Copenhagen, the two municipalities are highly integrated, which is why we include Frederiksberg in our analysis of violence in Copenhagen.

The so-called anticipatory benefits are a well-known phenomenon in crime prevention (Smith, Clarke, & Pease, 2002). Specifically, data on weekly spending at restaurants and bars in Denmark, published by a major Danish bank (“Danske Bank”), indicate that people went out less in the weeks before the lockdown. Specifically, this might have been influenced by the many media reports early in the pandemic about people contracting the coronavirus in a nightlife setting in an Austrian ski resort.

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2022.101884.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Andresen M.A., Hodgkinson T. Somehow I always end up alone: COVID-19, social isolation and crime in Queensland, Australia. Crime Science. 2020;9(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby M.P. Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science. 2020;9:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham P., Brantingham P. Criminality of place. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. 1995;3(3):5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burton R., Henn C., Lavoie D., O’Connor R., Perkins C., Sweeney K.…Sheron N. A rapid evidence review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: An English perspective. The Lancet. 2017;389:1558–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campedelli G.M., Favarin S., Aziani A., Piquero A.R. Disentangling community-level changes in crime trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chicago. Crime Science. 2020;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L.E., Felson M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review. 1979;44(4):588–608. doi: 10.2307/2094589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conrow L., Aldstadt J., Mendoza N.S. A spatio-temporal analysis of on-premises alcohol outlets and violent crime events in Buffalo, NY. Applied Geography. 2015;58:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Goeij M.C., Suhrcke M., Toffolutti V., van de Mheen D., Schoenmakers T.M., Kunst A.E. How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: A realist systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;131:131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vocht F., Heron J., Campbell R., Egan M., Mooney J.D., Angus C., Hickman M. Testing the impact of local alcohol licencing policies on reported crime rates in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2017;71(2):137–145. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejrnæs, A., Scherg, R. H., Cold, A. E. E., & Staunstrup, J. (2021). Natteliv og vold: Undersøgelse af voldskriminaliteten under nedlukningen af nattelivet https://dkr.dk/materialer/vold-og-voldtaegt/natteliv-og-vold pga. corona.

- Gerell M., Kardell J., Kindgren J. Minor Covid-19 association with crime in Sweden. Crime Science. 2020;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00128-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G., Holmes J., Studer J. Are alcohol outlet densities strongly associated with alcohol-related outcomes? A critical review of recent evidence. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2016;35(1):40–54. doi: 10.1111/dar.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff E.R., Lockwood B. Criminogenic facilities and crime across street segments in Philadelphia: Uncovering evidence about the spatial extent of facility influence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2014;51(3):277–314. doi: 10.1177/0022427813512494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys D.K., Eisner M.P. Do flexible alcohol trading hours reduce violence? A theory-based natural experiment in alcohol policy. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;102:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kommune K. Copenhagen; The City of: 2020. Statistik over alkoholbevillinger og nattilladelser i København september 2020 [Statistics on on-premises alchohol licenses in the City of Copenhagen] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K., Jones C., McElduff P., Barker D. Effects of restricting pub closing times on night-time assaults in an Australian city. Addiction. 2011;106(2):303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K., McElduff P., Miller P. Restrictions in pub closing times and lockouts in Newcastle, Australia five years on. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33(3):323–326. doi: 10.1111/dar.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton S., Dixon A., Farrell G. Six months in: Pandemic crime trends in England and Wales. Crime Science. 2021;10(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40163-021-00142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton S., Dixon A., Farrell G. Small area variation in crime effects of COVID-19 policies in England and Wales. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2021;75(June) doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine N. The location of late night bars and alcohol-related crashes in Houston, Texas. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2017;107:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightowlers C., Pina-Sánchez J., McLaughlin F. The role of deprivation and alcohol availability in shaping trends in violent crime. European Journal of Criminology. 2021 doi: 10.1177/14773708211036081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M. Alcohol outlet density and assault: A spatial analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(4):619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez E., Rosenfeld R. Crime, quarantine, and the U.S. coronavirus pandemic. Criminology & Public Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12557. April, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., Short M.B., Sledge D., Tita G.E.…Brantingham P.J. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nivette A.E., Zahnow R., Aguilar R., Ahven A., Amram S., Ariel B.…Eisner M.P. A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;1–10 doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01139-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J., Morgan A. 2020. Property Crime during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic forecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J.L., Morgan A., Piquero A.R. COVID-19 and social distancing measures in Queensland, Australia, are associated with short-term decreases in recorded violent crime. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2020;1–25 doi: 10.1007/s11292-020-09441-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Jennings W.G., Jemison E., Kaukinen C., Knaul F.M. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2021;101806 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore W.A., Grubesic T.H. Alcohol outlets and community levels of interpersonal violence: Spatial density, outlet type, and seriousness of assault. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2013;50(1):132–159. doi: 10.1177/0022427810397952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R., Lopez E. Council on criminal justice. 2.72. 2020. Pandemic, social unrest, and crime in U.S. cities. [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I., Norström T. The impact of small changes in bar closing hours on violence. The Norwegian experience from 18 cities. Addiction. 2012;107(3):530–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J.P., Moore S.C., Long A., Mercer Kollar B.L.M., Sumner S.A. Association between COVID-19 lockdown measures and emergency department visits for violence-related injuries in Cardiff, Wales. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2021;325(9):885–887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.J., Clarke R.V., Pease K. Anticipatory benefits in crime prevention. Crime Prevention Studies. 2002;13:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tingerstedt C., Mäkelä P., Agahi N., Moan I.S., Bye E.K., Parikka S.…Lau C.J. Comparing older people’s drinking habits in four Nordic countries: Summary of the thematic issue. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift. 2020;37(5):434–443. doi: 10.1177/1455072520954326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.J.J., Fung T., Weatherburn D. The impact of the COVID-19, social distancing, and movement restrictions on crime in NSW, Australia. Crime Science. 2021;1–14 doi: 10.1186/s40163-021-00160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R., Grubesic T.H., Kang W. Urban Analytics and City Science; Environment and Planning B: 2020. Spatiotemporal patterns of alcohol outlets and violence: A spatially heterogeneous Markov chain analysis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson C., Livingston M., Room R. Impacts of changes to trading hours of liquor licences on alcohol-related harm: A systematic review 2005–2015. Public Health Research and Practice. 2016;26(4) doi: 10.17061/phrp2641644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material