The COVID‐19 pandemic has exposed the importance of mental health, a previously overlooked aspect of health. Physicians who treat venous thromboembolism (VTE) may not consider mental health sequelae such as psychological distress, fear, and anxiety to fall within their specialist remit, although most would agree that optimal VTE management results in full patient recovery. Complications such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, postthrombotic syndrome, and bleeding are well characterized in the thrombosis literature, and much research has focused on optimizing therapy to mitigate these adverse outcomes. However, patients who have experienced pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis consistently report other mental health complications such as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder. 1 , 2 , 3 In fact, when patients with VTE are interviewed about their lived experience, they are seldom preoccupied by their physical recovery and instead focus on psychological distress, worry, and well‐being.

There is a mismatch between physician goals and patient needs in relation to VTE management, a mismatch that can no longer go unrecognized and unaddressed. Symptoms such as anxiety are more prevalent among patients with VTE than patients experiencing other life‐threatening conditions such as acute coronary syndrome. 4 Recurrent themes contributing to excess psychological distress include the frequency of pulmonary embolism misdiagnosis, 2 , 3 delayed assessments, not being taken seriously by physicians, and inconsistent information regarding the diagnosis. 5

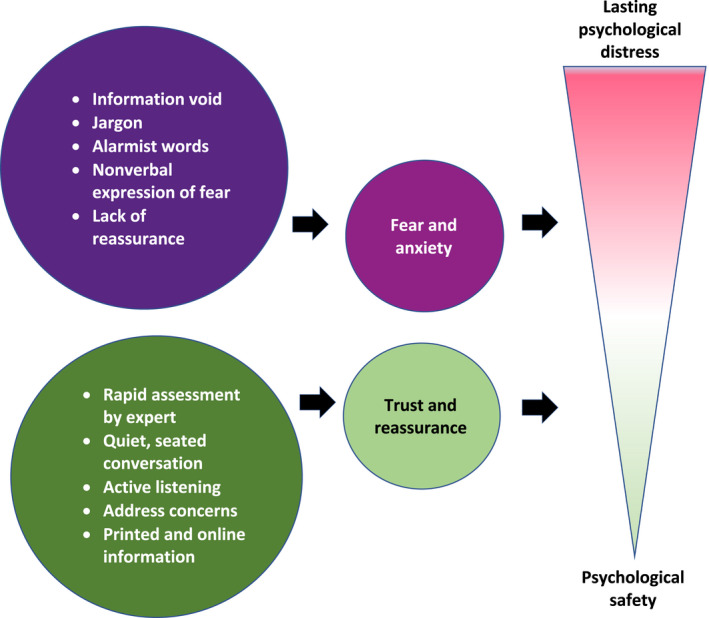

Patients who report lasting psychological distress after pulmonary embolism are more likely to recall their diagnosis delivery as a traumatic event. 1 In this issue of Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Hernandez‐Nino et al. explore how health care practitioners can both cause and exacerbate the psychological distress arising from VTE diagnosis. The impact of physician word choice is striking and paints a picture of physicians so immersed in disease management that they cannot step back to see a patient who does not understand what is happening and who is being excluded from participating in the conversation. Jargon such as saddle is unhelpful and confusing to patients, while alarmist terms like “time bomb” contribute to patient fear and distress. This is a stark contrast to other physician activities, such as breaking bad news, where physicians in training develop highly tuned communication skills. Physicians would never use technical terms such as code blue when telling a family member of a death nor use euphemisms such as passed or gone.

Hernandez‐Nino et al. also point to a lack of effective information sharing between health care provider and patient. This information void has been reported elsewhere, 2 , 5 causing feelings of abandonment and anger toward physicians. The information void is a barrier to patient participation in VTE management decisions, making patients feel they are bystanders in their own care. 2 The resultant perceived lack of control can lead to further mistrust in health care providers, and it is not unusual for patients to seek out new physicians. 2 , 5 Patients describe lack of information at every level: from the pathophysiology of VTE, such as understanding what VTE is and whether it can cause a stroke or heart attack, 1 to the expected prognosis and practicalities of when to return to work. 2

Fallout from the information void includes information seeking from the Internet, family members, and other health care providers, reasonable options at face value. However, Internet searching and advice from friends and family likely exacerbate anxiety. Instead of addressing the root problem (lack of information about the condition), physicians often view repeated patient visits as a nuisance.

No physician would want to be the vessel of patient distress, so how could these situations arise? Paradoxically, pulmonary embolism testing causes anxiety among physicians. Fear of pulmonary embolism is pervasive among physician culture. 6 Most emergency physicians will manage a patient with acute pulmonary embolism only once every few months and may rely on a pulmonary embolism response team to determine acute management. In this study, patients recall sudden changes in provider behavior once the diagnosis is known: closer monitoring, additional physicians, and a more serious demeanor. It is understandable that this causes confusion for patients since nothing about their condition has changed. Hernandez‐Nino et al. show how an imbalance between reassurance and alarm, coupled with little or incomplete information, can set the perfect environment for fear, distress, and anxiety.

How can we do better? Physician situational awareness is essential to improving patient outcomes and patient satisfaction. Taking responsibility for both the physical and mental health repercussions of VTE should be our central purpose. Good communication skills and empathy form the core of the solution. There is no substitute for taking time to talk with patients (Figure 1). Providing consistent information and messaging, explaining what VTE is (and what it is not), reviewing how it is managed and what patients can expect during their recovery is vitally important. These conversations should not be the exception but the rule for every patient diagnosed with VTE.

FIGURE 1.

The links between physician behaviour and patient distress

In practical terms, this means physicians who test and treat patients for VTE should have a firm understanding of patient prognosis and therapeutic options. When the diagnosing physician is unclear on these issues, patients should be rapidly assessed by an expert who has the time to share this information in a quiet and uninterrupted environment. It is particularly important that patients who re‐present to medical services (their family physician, the emergency department or clinic) have their concerns taken seriously and are allowed additional time with an expert to review information on their VTE diagnosis and treatment. All patients should be given standardized, printed information as well as a link to a patient information website and support group. Just as medicine addresses physical recovery from VTE, with some thought and empathy, we can also improve the mental health recovery of our patients.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Handling Editor: Dr Lana Castellucci

REFERENCES

- 1. Tran A, Redley M, de Wit K. The psychological impact of pulmonary embolism: a mixed‐methods study. Res Pract Thromb Haemos. 2021;5:301‐307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunter R, Lewis S, Noble S, Rance J, Bennett PD. “Post‐thrombotic panic syndrome”: a thematic analysis of the experience of venous thromboembolism. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22:8‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Noble S, Lewis R, Whithers J, Lewis S, Bennett P. Long‐term psychological consequences of symptomatic pulmonary embolism: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore T, Norman P, Harris PR, Makris M. Cognitive appraisals and psychological distress following venous thromboembolic disease: an application of the theory of cognitive adaptation. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2395‐2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rolving N, Brocki BC, Andreasen J. Coping with everyday life and physical activity in the aftermath of an acute pulmonary embolism: a qualitative study exploring patients’ perceptions and coping strategies. Thromb Res. 2019;182:185‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zarabi S, Chan TM, Mercuri M, et al. Physician choices in pulmonary embolism testing. Can Med Assoc J. 2021;193:E38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]