Abstract

Introduction

Multimorbidity is a major public health challenge, with a rising prevalence in low/middle-income countries (LMICs). This review aims to systematically synthesise evidence on the prevalence, patterns and factors associated with multimorbidity of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among adults residing in LMICs.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of articles reporting prevalence, determinants, patterns of multimorbidity of NCDs among adults aged >18 years in LMICs. For the PROSPERO registered review, we searched PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane libraries for articles published from 2009 till 30 May 2020. Studies were included if they reported original research on multimorbidity of NCDs among adults in LMICs.

Results

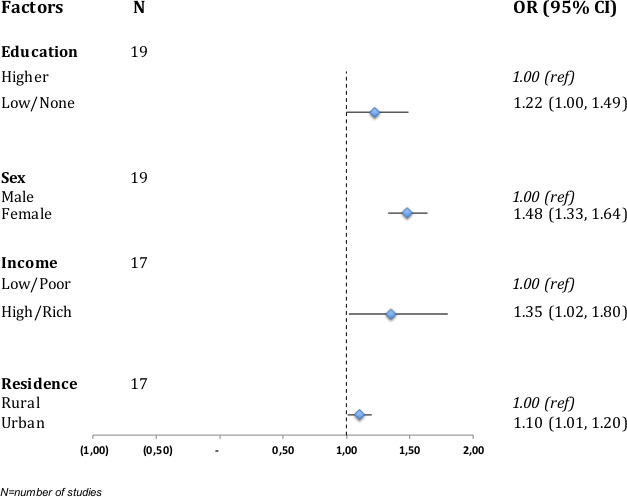

The systematic search yielded 3272 articles; 39 articles were included, with a total of 1 220 309 participants. Most studies used self-reported data from health surveys. There was a large variation in the prevalence of multimorbidity; 0.7%–81.3% with a pooled prevalence of 36.4% (95% CI 32.2% to 40.6%). Prevalence of multimorbidity increased with age, and random effect meta-analyses showed that female sex, OR (95% CI): 1.48, 1.33 to 1.64, being well-off, 1.35 (1.02 to 1.80), and urban residence, 1.10 (1.01 to 1.20), respectively were associated with higher odds of NCD multimorbidity. The most common multimorbidity patterns included cardiometabolic and cardiorespiratory conditions.

Conclusion

Multimorbidity of NCDs is an important problem in LMICs with higher prevalence among the aged, women, people who are well-off and urban dwellers. There is the need for longitudinal data to access the true direction of multimorbidity and its determinants, establish causation and identify how trends and patterns change over time.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019133453.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Inclusion of most studies (14/36 articles) from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) ensured standardisation of methods of measurements and data collection.

The included studies had large sample sizes, which ensured adequate statistical power to detect even a small effect of interest.

Recall and self-declaration bias due to self-reported outcome may result in under/over estimation of the true prevalence of multimorbidity.

Assessment of the determinants of multimorbidity did not take the heterogeneity and clusters of conditions into consideration.

Involving patients with varied characteristics and from a wide range of settings may contribute to substantial heterogeneity.

Introduction

Although the burden of diseases in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) has classically been infectious, changes in demographic patterns as a result of the interplay between urbanisation, life-style and culture, has led to emerging non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in LMICs.1 2 The NCD burden is estimated to increase by 27% in the African region in the next 10 years, while Western Pacific and South-East Asia will account for the highest absolute number of deaths from NCDs.3

Coexistence of one or more chronic diseases in an individual is commonly denoted as multimorbidity.4 5 With the increasing prevalence of NCDs in LMICs,6 many of which share common risk factors, the prevalence of multimorbidity of NCDs will continue to rise. There is, however, a substantial difference in the burden of NCDs between LMICs and high-income countries (HICs) due to the difference in drivers, such as promotion of healthier lifestyles and providing equitable healthcare by instituting appropriate government policies.7 While research investigated common pathways on NCD multimorbidity in HICs, it is unclear if this is also valid for LIMCs.8 It is therefore important to identify common NCD multimorbidity patterns and pathways that are specific to LMICs.

Studies undertaken so far predominantly used self-reported measures and show multimorbidity to be associated with decreased quality of life, increased healthcare utilisation and costs in primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare settings,4 5 9–12 just as reported in HICs.13 14 There is also limited information on the distribution of patterns of multimorbidity, their size, their drivers and their risk factors in LMICs. There are a few studies indicating that multimorbidity in LMICs is more frequent in women and that it starts at an earlier age than in HICs, but these studies are scattered.15 16 In order to address and manage the increasing number of people with multimorbidity, it is important to assess the burden of multimorbidity as well as the combinations of NCDs and their patterns in LMICs. A recent scoping review of that summarised the prevalence and determinants of multimorbidity chronic NCDs in LMICs reported prevalence ranging from 3.2% to 90.5%.6 This review builds on the previous scoping review by adopting systematic methods and meta-analysis to synthesise the evidence on the prevalence, patterns and factors associated with multimorbidity of NCDs among adults residing in LMICs. We further showed the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity of NCDs according to country’s income level classification by the World Bank.

Methods

Review framework and patient and public involvement

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported according to the recommendations outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement17 (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2021-049133supp001.pdf (76.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This is a meta-analysis based on study-level data and no individual-level data were involved in the study or in defining the research question or outcome measures. It was not possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Search strategy

A structured search was done in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library for articles published in English from 2009 until April 2020. Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and their combinations used in the searches included “Multiple Chronic Conditions”, “Multimorbidity”, “Comorbidity”, “Non-Communicable Diseases”, “Developing Countries”, “Cardiovascular Diseases”, “Neoplasms”, “Lung Diseases, Obstructive”, “Diabetes Mellitus” and “Mental Disorders”, “Hypertension”. In addition, the reference lists and bibliographies of the included articles were examined to identify any other relevant article. The detailed search strategy is provided as online supplemental file 2.

bmjopen-2021-049133supp002.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they (i) reported original research on multimorbidity of NCDs, (ii) included adults aged 18 years and above and residing in LMICs, (iii) conducted in any of these study settings; community, residential care homes, primary care, secondary care, tertiary care and specialised care centres/institutions; or at the regional level using data from primary research, demographic and health surveys, or demographic and health surveillance systems. We defined LMICs according to the World Bank’s Country and Lending Group List.18 We excluded studies conducted in HICs. Studies published in languages other than English and studies on comorbidity (studies that recruited patients based on an index disease or primary disease of interest) were also excluded. However, we included comorbidity in the search strategy to enable us to capture and scrutinise studies that used the terms comorbidity and multimorbidity interchangeably or incorrectly.

Definition of terms/concepts

We defined multimorbidity of NCDs as co-occurrence of two or more chronic non-communicable health conditions in the same individual.8 Prevalence of multimorbidity of NCDs was defined as the proportion of people with two or more chronic NCDs in the study population.8 Patterns of multimorbidity NCDs were assessed by considering the frequencies and distributions of NCDs among individuals, regions and countries.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (OAA, AMF) extracted data from the included articles. In case of divergent opinions, KK-G and DB were consulted. Information extracted included author(s) name, year of publication and study country, survey/source of data, sample size, method of data collection, number of NCDs, multimorbidity definition, prevalence and factors associated with multimorbidity. The following summary measures were included: prevalence, odds ratio (OR), prevalence risk ratios and relative risk ratio with their 95% CI for the association between risk factors/determinants and NCD multimorbidity.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies.19 This tool was used to appraise the reliability, validity, generalisability and overall quality of the included studies using 14 criteria. This included clearly stated research question and objective, clearly specified study population, adequate participation rate, similar subject selection/recruitment and uniform application of eligibility to all participants, sample size estimation, exposure measurement before outcome, sufficient time frame to detect an association, examination of different levels of exposure, multiply exposure measurement over time, valid outcome assessment, detection bias, loss to follow-up and adjustment of confounding variables. The tool provides general guidance to determine the overall quality of the studies and to grade their level of quality as good, fair or poor.

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies that provided sufficient data were used in the meta-analyses using Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) software.20 For multi-country studies with sufficient analysis of country level data, findings from individual countries were included separately in the meta-analyses. Findings of the remaining studies were presented in a narrative format. We pooled the OR (95% CI) for the association between sex, education, income, residence (rural/urban) and multimorbidity. A pooled OR of the association between age and multimorbidity was not estimated due to the variation in reference age categories whereas smoking, physical activity and alcohol consumption were not meta-analysed due to the limited number of studies that reported on them. The log OR and SEs were combined in RevMan using the generic inverse-variance.21 22 We performed a random effect analysis, and heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane’s Q and degree of inconsistency (I2).23 The pooled prevalence of multimorbidity was estimated using Open Meta (analyst) software.24 The pooled prevalence was further stratified according to different regions in LMICs. The robustness of the pooled estimates was assessed by conducting a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis.25 All analyses were considered statistically significant at the two-sided 5% level (p<0.05).

Results

The electronic database and reference list search yielded 3272 articles, while 3134 articles remained after removal of duplicates. After the title and abstract screening, 68 articles were deemed potentially relevant. Twenty-nine articles were further excluded because they were conducted on communicable diseases (n=18), in non-LMICs (n=2), had poor quality (n=1) or based on other reasons such as presence of an index disease, or assessed multimorbidity in all ages without a separate report for adult above 18 years (n=8). We included 39 studies for the current review (figure 1). Some of the studies reported results from multiple countries, which were included individually in the analyses. For example, Bao et al26 included analyses from seven countries; Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, China. Agrawal and Agrawal,27 Garin et al28 and Christian et al29 each reported findings from six countries; China, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa and Ghana. Zhou et al30 reported findings from India, China, and Bangladesh while Kunna et al31 assessed multimorbidity in China and India. Table 1 shows all the countries or regions where multimorbidity of NCDs were conducted.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for study inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| Author | Country/region | Inclusion criteria | Study design | Survey/source of data | Sampling characteristics | Field year | Sample size | Age range (years) |

Data collection | No of NCDs | Multi-morbidity definition | Prevalence (%) | Quality of included studies |

| Afshar et al (27 LMICs)16 | Africa, Central and South America, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, South Asia, South East Asia |

Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHS | Probabilistic | 2001–2004 | 25 761 | ≥18 | Self-report | 6 | ≥2 | Ranges from 1.7 to 15.2; Africa (3.6–11.2) Central and South America (5.7–13.4) Eastern Europe and Central Asia (7.6–15.0) South Asia (3.9–7.8) Southeast Asia (1.7–15.2) Mean global prevalence (95 CI) 7.8 (7.8 to 7.8)* |

Good |

| Agrawal and Agrawal27 | China | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | China (15048); (India 12198); Mexico (2725); Russia (4946); South Africa (4227); Ghana (5571) | ≥18 | Self-report+medication use+SBD | 9 | ≥2 | 22.0–50.0: China (22.0); India (24.0); Mexico (27.0); Russia (50.0); South Africa (32.0); Ghana (23.0) |

Good |

| Arokiasamy et al4 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 42 236 | ≥18 | Self-report+medication use+SBD | 9 | ≥2 | 21.9 | Good |

| Aye et al54 | Myanmar | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | Household survey | Probabilistic | 2016 | 4859 | ≥60 | Self-report | 14 | ≥2 | 33.2 | Good |

| Bao et al 26 | Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, China | Prevalence | Population based Cohort | Household survey | NR | 2003–2010 | 15 027 | ≥65 | Self-report+physical examination | 15 | ≥2 | Ranges from 31.0 to 68.0; China (31.0); Peru (49.0) Cuba (58.0), Venezuela (60.0), Mexico (60.0), Dominican Republic (68.0) |

Fair |

| Chen et al57 | China | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | CHARLS | Probabilistic | 2011–2012 | 3737 | ≥45 | Self-report | 16 | ≥2 | 46.0 | GOOD |

| Christian et al29 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 42 487 | ≥50 | Self-report | 8 | ≥2 | Ranges from 8.8 to 50.2: Ghana (8.8), India (16), China (20.3), Mexico (20.8), South Africa (20.8%), Russia (50.2) |

Good |

| Ebrahimoghli et al32 | Iran | Prevalence | Retrospective cohort study | IHIO | All beneficiaries of IHIO | 2013–2016 | 481 733 | ≥18 | ATC CS | 18 | ≥2 | 21.5 | Fair |

| Garin et al28 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence determinants and patterns | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | China (13157), Ghana (4305), India (6560), Mexico (2301), South Africa (3763), Russia (3836) | ≥50 | Self-report +medication use +SBD | 12 | ≥2 | Ranges from 45.1 to 72.0: China (45.1), Ghana (48.3), India (57.9), Mexico (64.0), South Africa (63.4), Russia (72.0) |

|

| Hien et al33 | Burkina Faso | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | Household survey | Probabilistic | 2012 | 389 | ≥60 | Self-report+clinical examination+medical record review | 16 | ≥2 | 65.0 | Good |

| Jawed et al55 | Pakistan | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | The IMPACT study | Probabilistic | 2015–2016 | 1500 | ≥30 | Self-report+medication use+SBD | 16 | ≥2 | 48.6 | Good |

| Jerliu et al46 | Kosovo | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | Community survey | Probabilistic | 2011 | 2265 | ≥65 | Self-report | 7 | ≥2 | 45.0 | Good |

| Jovic et al42 | Serbian | Prevalence, patterns | Cross-sectional | NHS-Serbia | Probabilistic | 2013 | 13 103 | ≥20 | Self-report | 12 | ≥2 | 26.9 | Good |

| Jankovic et al43 | Serbian | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | NHS-Serbia | Probabilistic | 2013 | 13 765 | ≥20 | Self-report | 13 | ≥2 | 30.2 | Good |

| Khan et al45 | Bangladesh | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | Household survey | Probabilistic | 2014–2016 | 12 338 | ≥35 | Self-report+medication use+SBD | 6 | ≥2 | 8.4 | Good |

| Khanam et al48 | Bangladesh | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | HDSS | Probabilistic | 2003–2004 | 452 | ≥60 | Self-report+physical examination+blood test | 9 | ≥2 | 53.7 | Good |

| Kumar et al47 | India | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | Household survey | NR | 2012–2013 | 58 590 | ≥20 | Self-report | 5 | ≥2 | 0.7 | Fair |

| Kunna et al31 | China, Ghana | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | China (11 814); Ghana (4050) | ≥50 | Self-report+SBD | 7 | ≥2 | China (29.7); Ghana (30.2) | Good |

| Koyanagi et al87 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2011 | 32 715 | ≥50 | Self-report+SBD | 10 | ≥2 | 49.8 | Good |

| Lee et al9 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 39 213 | ≥18 | Self-report | 9 | ≥2 | Varies from 3.9 in Ghana-33.6 in Russia | Good |

| Mini and Thankappan50 | India | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | UNFPA | Probabilistic | 2011 | 9852 | ≥60 | Self-report | 12 | ≥2 | 30.7 | Good |

| Nugraha et al41 | Indonesia | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | Community survey | Probabilistic | 2018 | 427 | ≥60 | Self-report | 15 | ≥2 | 60.7 | Good |

| Nunes et al40 | Brazil | Prevalence and patterns | Cross-sectional | Household survey | Probabilistic | 2008 | 1593 | ≥60 | Self-report | 17 | ≥2 | 81.3 | Good |

| Nunes et al34 | Brazil | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | PNS | Probabilistic | 2013 | 60 202 | ≥18 | Self-report | 22 | ≥2 or≥3 | 22 for ≥2 and 10.2 for ≥3 | Good |

| Pati et al58 | India | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007 | 10 973 | ≥18 | Self-report | 9 | ≥2 | 8.9 | Good |

| Pati et al39 | India | Prevalence and patterns | Cross-sectional | Primary healthcare | Probabilistic | 1649 | ≥18 | Self-report | 21 | ≥2 | 28.3 | Good | |

| Pengpid and Peltzer36 | Mekong | Prevalence, determinants | Cross-sectional | Primary healthcare | Probabilistic | NR | 6236 | ≥18 | Self-report | 21 | ≥2 | 72.6 (28.6 had 2, 22.4 had 3 and 21.6 had ≥24 chronic conditions) | Good |

| Phaswana-Mafuya et al52 | South Africa | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2008 | 3840 | ≥50 | Self-report | 8 | ≥2 | 22.5 | Good |

| Price et al53 | Malawi | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | Household survey | No sampling: all adults | 2013–2016 | 28 891 | ≥18 | Self-report+medication use+patient health record+clinical test | 3 | ≥2 | 4.0 | Good |

| Rehr et al51 | Northern Jordan | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | UNHCR | Probabilistic | 2016 | 8041 | ≥18 | Self-report | 6 | ≥2 | 44.7 | Good |

| Rzewuska et al35 | Brazil | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | PNS | Probabilistic | 2013 | 60 202 | ≥18 | Self-report+SBD | 14 | ≥2 | 24.2 | Good |

| Sum et al44 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence and patterns | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 41 557 | ≥18 | Self-report+SBD | 9 | ≥2 | 18.9 | Good |

| Vadrevu56 | India | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | Household survey | Probabilistic | 2009 | 815 | ≥40 | Self-report+SBD | 6 | ≥2 | 44.1 | Good |

| Vancampfort et al88 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 34 129 | ≥50 | Self-report+SBD | 11 | ≥2 | 45.5 | Good |

| Vancampfort et al89 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 34 129 | ≥50 | Self-report+SBD | 11 | ≥2 | 45.5 | Good |

| Vancampfort et al49 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, South Africa, Russia | Prevalence and determinants | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2010 | 14 585 | ≥65 | Self-report+SBD | 11 | ≥2 | 60.2 | Good |

| Waterhouse et al90 | South Africa | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHO SAGE | Probabilistic | 2007–2008 | 3055 | ≥50 | Self-report | 8 | ≥2 | 13.2 | Good |

| Woldesemayat et al60 | Ethiopia | Prevalence, patterns and determinants | Cross-sectional | Healthcare | NR | 2016 | 411 | ≥18 | Self-report+medical card | 18 | ≥2 | 17.8 | Good |

| Zhou et al30 | Bangladesh, India, China | Prevalence | Cross-sectional | WHS | Probabilistic | 2002–2004 | Bangladesh (5507); India (9199); China (3990) | ≥18 | Self-report | 9 | ≥2 | Bangladesh (28.8); India (34.4); China (14.3) | Good |

*Include prevalence from 27 LMICs and 1 high-income country.

ATC CS, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; BDHS, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey; CHARLS, China Health and Population Fund; HDSS, Health and Demographic Surveillance System; IHIO, Iranian Health Insurance Organization; LMIC, low/middle-income country; NCDs, non-communicable diseases; PNS, Pesquisa Nacional de Saude (Brazillian National Health Survey); SA-NIDS, South Africa National Income Dynamics Study; SBD, symptom based diagnosis; UNHCR, United Nations High Commission for Refugees; WHO-SAGE, WHO Study on Global AGEing and adults health; WHS, World Health Survey.

All included articles were cross-sectional except two studies that were cohort studies.26 32 A total of 1 220 309 individuals were included and the sample size ranged from 38933 to 60 202.34 35 NCDs were assessed through self-report in all included studies, or in combination with a health insurance database,32 or medication use and clinical test. One study assessed based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. The number of self-reported NCDs ranged from 3 to 22. All studies defined multimorbidity as coexistence of two or more chronic NCDs, except one study which defined multimorbidity as a count of 21 chronic health conditions36 (table 1).

Most of the studies were of good quality. Three included articles were judged to be of fair quality.26 32 37 One study was excluded because of having a small sample size, and a lack of data or non-robust methods.38 Twenty-one of the included studies did not give information about missing data handling4 26 29–31 33 34 36 39–52 (online supplemental file 3).

bmjopen-2021-049133supp003.pdf (121.7KB, pdf)

The overall prevalence of multimorbidity of NCD varied from 0.7% (in a population aged ≥20 years in a rural community in Western India) to 81.3% (in an elderly population aged ≥60 years in Southern Brazil).40 47 A study that assessed prevalence of multimorbidity among adults ≥18 years in 27 LMICs using the World Health Surveys reported a mean prevalence ranging from 1.7% (95% CI 1.4 to 2.0) in Myanmar to 15.2% (95% CI 14.3 to 16.0) in Nepal.16 In studies that combined self-reported diseases with symptom based diagnosis, medication use/medical card review, prevalence varied between 4.0% and 72% in people ≥18 years.36 53 The overall prevalence of multimorbidity was 36.4% (95% CI 32.2% to 40.6%) as shown in figure 2. In a subgroup analysis, the pooled prevalence according to the countries’ income levels was 39.3% (95% CI 34.5% to 44.1%) for upper middle-income countries (MICs) (online supplemental figure 1a) and 29.2% (95% CI 23.0% to 35.4%) for lower MICs (online supplemental figure 1b). We did not pool the prevalence for low-income countries (LICs) because there were only three studies, with prevalence ranging from as low as 4.0% in Malawi to 65.0% in Burkina Faso. Subgroup analysis according to the World Bank regions of LMICs was 26.2% (95% CI 18.9% to 33.5%) for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA); 29.5% (95% CI 20.9% to 38.1%) for Asia; 31.8% (95% CI 25.7% to 37.8%) for East Asia; 33.1% (95% CI 10.4% to 55.8%) for Middle-East and North Africa (MENA); for Europe and Central Asia (excluding high income) 44% (95% CI 32.7% to 55.3%) and 50.4% (95% CI 35.6% to 65.2%) for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). According to the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, no single study had a substantial influence on the overall prevalence of NCD multimorbidity (online supplemental figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of pooled prevalence of multimorbidity in low/middle-income countries.

bmjopen-2021-049133supp006.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp007.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)

Age, sex, education, wealth/income, urban/rural setting and marital status were the most studied factors associated with multimorbidity of NCDs (online supplemental table 1). ORs for the association between major predictors and multimorbidity are shown in online supplemental table 2. Age was positively associated with multimorbidity of NCDs in 22 studies, whereas 3 studies28 48 49 found no association.

bmjopen-2021-049133supp004.pdf (112.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp005.pdf (204.3KB, pdf)

Figure 3 shows a forest plot of pooled OR for the association between major predictors and multimorbidity; details of the meta-analysis for the individual predictors are shown in online supplemental figure 3a–d). Women had significantly higher odds of multimorbidity compared with men in 11 studies,4 9 28 34–36 48 50 54–56 whereas 8 studies showed a non-significant association28 31 33 46 49 51 57 58 (online supplemental table 2). Fourteen studies (one study included six different country level results) were meta-analysed and the pooled OR for female sex and NCD multimorbidity was 1.48 (95% CI 1.33 to 1.64) (figure 3, online supplemental figure 3a). The association between education and multimorbidity was assessed in 31 studies. In most studies, the risk of multimorbidity was higher among those with a lower educational status,4 16 28 34–36 43 51 while four studies reported a lower risk of lower education statu.45 50 53 57 A meta-analysis of 13 studies (one study included six different country level results; one study included results for males and females) showed an OR of 1.22 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.49) for those with no formal education or lower educational attainment (figure 3, online supplemental figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of pooled ORs of factors associated with multimorbidity in low/middle-income countries.

bmjopen-2021-049133supp008.pdf (105.3KB, pdf)

The association between socioeconomic status (income/wealth) and multimorbidity was determined in 14 studies; 7 studies found an association with higher odds/risk/prevalence of multimorbidity for people in the most well-off class,9 28 31 45 48 50 53 while in 3 studies the odds/prevalence of multimorbidity was higher for people considered to be poor.4 28 31 The pooled OR from 10 studies (one study included six different country level results; one study included results for males and females) showed increased odds of NCD multimorbidity among people who are well-off, OR 1.35 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.80) (figure 3, online supplemental figure 3c). There were significantly higher odds/risk for multimorbidity of NCDs for urban areas.9 34 49 53 54 59 A meta-analysis of 10 studies (one study included six different country level results; two included results for males and females) showed a pooled OR of 1.10 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.20) for urban residence (figure 3, online supplemental figure 3d). There was a high degree of heterogeneity as depicted by high I2 >90% in the various meta-analyses conducted.

Three of the seven studies that assessed the association between multimorbidity of NCDs and physical activity/exercise showed significantly higher odds for those that do little or no physical activity,4 31 49 while the other five showed no significant relationship.31 36 45 53 60 Eight studies examined the relationship between obesity and multimorbidity; five articles found higher a positive association between multimorbidity of NCDs and obesity.4 27 31 45 56 In the WHO SAGE study among five LMICs, obese individuals were 2.3 times (95% CI 2.0 to 2.52) more likely to have multimorbidity compared with the non-obese when multimorbidity was compared with no disease.4 Eight studies assessed the association between smoking and multimorbidity, with a study conducted among the elderly from seven Indian urban and rural states reporting a positive association50 when compared with no NCD (OR: 1.22, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.37). Alcohol consumption was associated with higher odds of NCD multimorbidity.50 53

The patterns of reported NCD multimorbidity are shown in table 2. Seventeen studies assessed patterns of multimorbidity of NCDs using factor analysis,28 34 35 42 54 cluster analysis50 or descriptive methods.39 40 44 45 51 60 Sixteen out of the 17 studies that reported on patterns of multimorbidity were conducted in MICs, while only one study was conducted in LIC. Cardiometabolic and cardiorespiratory conditions were the most identified patterns seen in MICs, while cardiovascular, musculoskeletal system diseases and endocrine system diseases were observed in the only one study in LMICs (table 2). The highest prevalence of cardiometabolic pattern was 70.3% and 60.7% among males and females aged 20–40 years, respectively in MICs. Cardiometabolic, mental and respiratory conditions were present in both men and women in two MICs studies that stratified by sex.35 42 Mental disorder was also reported to cluster with other conditions such as cardiometabolic, respiratory and musculoskeletal conditions in studies conducted in Brazil, Serbia and a multi-country study in South Africa, Ghana, Mexico, Russia, Bangladesh, India and China.28 34 35 39 42 44

Table 2.

Patterns of multimorbidity reported in included studies

| Pattern | Study | Economy status | Diseases | Prevalence % (95% CI) |

| Cardiometabolic | Garin et al28 (China) | MIC | Diabetes, obesity, hypertension, angina, stroke, cataract | NR |

| Garin et al28 (Ghana, India, Mexico) | MIC | Diabetes, obesity, hypertension | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (Russia) | MIC | Diabetes, obesity, hypertension, angina, stroke, cataract, arthritis, edentulism, depression | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (South Africa) | MIC | Diabetes, obesity, hypertension, angina, stroke, arthritis, edentulism | NR | |

| Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male (age 20–44 years): Cardiometabolic Age 45–64 years: Cardiometabolic Age 65+ years: Cardiometabolic |

70.3 39.2 29.5 |

|

| MIC | Female (Age 20–44 years): Cardiometabolic Age 45–64 years: Cardiometabolic Age 65+ years: Cardiometabolic |

60.7 53.2 33.2 |

||

| Khan et al45 | MIC | Hypertension, diabetes, CVD; Hypertension, diabetes, stroke; Hypertension, diabetes, cancer; Hypertension, CVD, stroke Diabetes, CVD, stroke Hypertension, diabetes, CVD, stroke |

0.6 0.4 0.0 0.3 0.3 0.6 |

|

| Mini and Thankappan50 | MIC | High blood pressure, diabetes | 4.7 | |

| Nunes et al34 | MIC | High blood pressure, heart attack, angina, heart failure, stroke, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, arthritis/rheumatism | NR | |

| Rehr et al51 | MIC | Diabetes and hypertension; Diabetes, hypertension and CVD; Hypertension and CVD; Diabetes, hypertension and thyroid disease |

17.6 (15.9 to 19.5) 8.1 (6.9 to 9.7) 7.1 (5.9 to 8.4) 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) |

|

| Rzewuska et al35 | MIC | Male and female: diabetes, stroke, cardiovascular disorders; high blood cholesterol, hypertension | NR | |

| Cardiovascular | Aye et al54 | MIC | Coronary heart disease, Heart failure | NR |

| Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male (age 45–64 years): cardiovascular Age >65 years: cardiovascular Female (45–64 years): cardiovascular Age >65 years: cardiovascular |

22.8 28.7 29.6 18.9 |

|

| Rehr et al51 | MIC | Hypertension and CVD | 7.1 (5.9 to 8.4) | |

| Woldesemayat et al60 | LIC | Cardiovascular and endocrine system diseases | 2.4 | |

| Cardiorespiratory | Aye et al54 | MIC | Asthma, COPD, hypertension, diabetes, stroke | NR |

| Garin et al28 (China) | MIC | Angina, asthma, COPD, depression, arthritis, cataract | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (Ghana) | MIC | Angina, asthma, COPD | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (India) | MIC | Angina, asthma, COPD, depression | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (Mexico) | MIC | Angina, asthma, COPD, stroke, depression, arthritis, cataract | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (South Africa) | MIC | Angina, asthma, COPD, stroke, depression, arthritis | NR | |

| Rehr et al51 | MIC | Hypertension and chronic respiratory condition | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.9) | |

| Khan et al45 | MIC | Hypertension, diabetes, COPD | 0.1 | |

| Mental | Aye et al54 | MIC | Depression, mental illness | NR |

| Respiratory | Garin et al28 (Russia) | MIC | Asthma, COPD, cataract | NR |

| Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male (age 45–64): respiratory Age 65+ years: respiratory Female (age 45–64 years): respiratory 16.8 Age 65+ years: respiratory |

13.7 16.0 14.5 |

|

| Rzewuska et al35 | MIC | Male and female: Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | NR | |

| Musculoskeletal | Aye et al54 | MIC | Arthritis, osteoporosis | NR |

| Ocular+musculoskeletal +cardiorespiratory |

Aye et al54 | MIC | Asthma, COPD, cataract, arthritis, osteoporosis, asthma, COPD, hypertension, diabetes, stroke | NR |

| Mini and Thankappan50 | MIC | Arthritis, hypertension; Arthritis, cataract |

7.5 5.3 |

|

| Nunes et al40 | MIC | HBP, heart problem, eyesight problem, spinal column disease, rheumatism | 10.6 to 5.5 | |

| Pati et al39 | MIC | Hypertension+APD+diabetes, Hypertension+APD+CBA; Hypertension+arthritis+diabetes; Hypertension+arthritis+CBA; APD+visual impairment+CBA; APD+visual impairment+arthritis Athritis+CBA+CLD; Athritis+CBA+visual impairment APD+hypertension/visual impairment/CBA/arthritis/diabetes/CLD/deafness Hypertension+visual impairment/CBA/visual impairment/arthritis/deafness Arthritis+visual impairment/CBA/diabetes |

NR | |

| Sum et al44 | MIC | Age 18–49 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD, Age 50–64 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD Age >64 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD, Hypertension+cataract |

4.99 4.13 1.90 19.08 17.08 9.79 33.77 29.73 16.44 15.27 |

|

| Mental+musculoskeletal | Garin et al28 (China) | MIC | Arthritis, depression, stroke, cataract | NR |

| Garin et al28 (Ghana) | MIC | Arthritis, depression | NR | |

| Garin et al28 (India) | MIC | Arthritis, depression, cataract, angina | NR | |

| Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male age ≥65 years: mechanical/mental/metabolic Female age ≥65 years: mechanical/mental/metabolic |

25.8 32.3 |

|

| Nunes et al34 | MIC | Arthritis/rheumatism, spinal column problem, spinal column problem, asthma/wheezy bronchitis, COPD, work-related muscle-skeletal disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, kidney problem | NR | |

| Rzewuska et al35 | MIC | Male and female: Arthritis or rheumatism, high blood cholesterol, MSK-D related to work, any chronic back problem, chronic renal insufficiency, schizophrenia, bipolar, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression | NR | |

| Sum et al44 | MIC | Age: 18–49 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD, Hypertension+depression |

4.99 4.13 1.90 1.67 |

|

| Cardio metabolic+musculoskeletal | Mini and Thankappan50 | MIC | Arthritis, hypertension | 7.5 |

| Nunes et al40 | MIC | HBP, rheumatism, spinal column disease; HBP, heart problem, spinal column disease; HBP, heart problem, cognitive impairment; HBP, spinal column, falls | 10.6 to 5.7 | |

| Pati et al39 | MIC | Hypertension, arthritis, diabetes/CBA | ||

| Woldesemayat et al60 | LIC | Cardiovascular and musculoskeletal system diseases | 1.2 | |

| Cardio metabolic+musculoskeletal +mental |

Nunes et al40 | MIC | HBP, heart problem, cognitive impairment, depression | 10.6 to 5.2 |

| Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male: Age 45–64 years: Aggregate pattern, such as degenerative joint disease/arthrosis, depression, cardiovascular, kidney disease, stroke and malignancy Female: Aged 20–44 years: non-communicable pattern such as degenerative joint disease/arthrosis, depression, cardiovascular and malignancy |

24.3 13.3 |

|

| Cardio+metabolic+respiratory +musculoskeletal+mental |

Jovic et al42 | MIC | Male: Age 20–44 years: non-communicable pattern such as degenerative joint disease/arthrosis, depression, cardiovascular, respiratory, kidney disease and malignancy | 29.7 |

| Pati et al39 | MIC | Arthritis+CBA/visual impairment/chronic lung disease | NR | |

| Sum et al44 | MIC | Age 18–49 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD, Hypertension+depression Age 50–64 years: Hypertension+arthritis, Hypertension+angina, Hypertension+CLD |

4.99 4.13 1.90 1.67 19.08 17.08 9.79 |

APD, acid peptic disease; CBA, chronic back pain; CLD, chronic lung disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRD, cardiorespiratory disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LIC, low-income country; MIC, middle-income country; MSK-D, musculoskeletal disorder.

Discussion

This systematic review with meta-analyses of 39 studies shows that the overall prevalence of NCD multimorbidity in LMICs was 36% with substantial variation between studies. Prevalence differed by region and was observed to be lowest in SSA and highest in LAC region. According to income levels of countries, the prevalence of NCD multimorbidity was higher among upper MICs and as compared with lower-middle income countries. Older age, female sex, higher income and urban residence increased the odds of having NCD multimorbidity. Cardiometabolic and cardiorespiratory patterns of multimorbidity of NCDs were most common; in addition, multimorbidity of mental disorders with respiratory, musculoskeletal and cardiometabolic conditions was observed.

An important finding from our review is the large variation in the estimates of prevalence of multimorbidity of NCDs in LMICs. This may be explained by differences in definition/measurement of multimorbidity, study populations, demographics, study settings, self-reported diseases and the number of NCDs included. Similar variation was seen in reviews that focused on South Asia61 and HICs.62 63 A recent scoping review of multimorbidity of chronic NCDs in LMICs also found a wide variation in the prevalence of multimorbidity in LMICs (3.2%–90.5%), depending on population age and the number of conditions considered.6 Since prevalence estimates depend on the number and the type of chronic conditions included in the measurement of multimorbidity, there might be underreporting due to lack of data or undiagnosed conditions. To date, there is no valid standard measurement of multimorbidity indicating a need for a uniform definition and a reporting system for multimorbidity, as suggested by the Academy of Medical Science.8

The positive association of multimorbidity with age and female sex is consistent with a study comparing 27 LMICs and 1 HIC using the World Health Survey,16 other reviews on multimorbidity in South Asia and LIMCs6 39 as well as reviews from HICs.62 63 The meta-analyses showed higher odds of multimorbidity among women compared with men. While the association between these factors and multimorbidity is inconsistently reported, the sex-related differences in multimorbidity could be related to context related proxy for behavioural characteristics such as care seeking, that might influence the detection of multimorbidity.8 Women are more likely to have frequent healthcare consultations than men64 65 and might be able to self-report their health status than men. In addition, sex differences in socioeconomic status could also account for the discrepancy observed. Socioeconomic status affects general health functioning, including mental and physical health. Research show that women, in general, have lower socioeconomic status than men, which is in part related to gender inequality and could negatively affect health outcomes.66

In LMICs, people who are well-off in terms of income seem to be most affected by multimorbidity, in contrast with evidence from HIC8 that shows an inverse association. Few studies from HIC have, however, reported higher prevalence among people who are well-off.9 16 59 Contextually, people who are well-off in LMICs are generally less physically active and consume more fats, salt and processed food which could partly explain the higher prevalence of NCD multimorbidity.67 Further, they might be better educated, informed and have greater access to medical care and are more likely to receive disease diagnosis. The significantly higher odds for multimorbidity of NCDs seen in the urban areas may be due to under-reporting in rural areas as a result of poorer access to healthcare and healthcare insurance.68 In most LMICs, healthcare services are paid out of pocket for every inpatient and outpatient visit.9 People living in rural areas are less likely to have long-term healthcare insurance and also less likely to be provided with adequate healthcare.69 Furthermore, regional differences in lifestyle could also explain higher odds of multimorbidity of NCDs in people living in urban areas as residence in urban areas is associated with unfavourable diets and lower physical activity levels.70 71

This review identified various patterns of NCD multimorbidity across different regions in LMICs. Cardiometabolic and cardiorespiratory patterns of multimorbidity were most common and share major pathophysiological pathways and common risk factors such as smoking,72 73 partly explaining their clustering together. The frequent co-occurrence of cardiometabolic conditions and mental disorders among studies in LMICs as shown in this review is consistent with findings from HICs62 74 75 and highlights the importance of prevention and management policies addressing environmental and living conditions.76

Current evidence suggests a poorer health-related quality of life, worse clinical outcomes and an increased risk of premature mortality among patients with concurrent physical and mental health conditions than those who have physical conditions alone.77–79 Individuals with concurrent physical and mental health conditions are also found to have challenges with medication adherence, compromised self-management,80 high risk of adverse drug events,81 higher rates of healthcare utilisation. They are however at a risk of receiving suboptimal care for coexisting health conditions, leading to poorer health outcomes and increased mortality.82

Strength and limitations

A strength of this review is that most of the included studies from the database search were from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE), which ensured standardisation of methods of measurements and data collection. This review provides worldwide prevalence rates and predictors for multimorbidity. The standardised methods and large sample sizes of the underlying studies ensure a high qualitative standard of the report.

A main limitation of this review is that all studies included self-reported measures for data collection of multimorbidity, and very few collected physical or biochemical data. Self-reported disease is fairly accurate, and may be subject to recall and self-declaration bias, under or over reporting of outcome of interest.83 84 This may result in under/over estimation of the true prevalence of multimorbidity. The restriction of inclusion criteria to only studies conducted in English might have also led to studies from other LMICs, especially South America where Spanish dominates, leading to potential bias in the estimates. Generally, studies that assessed determinants of multimorbidity did not take the heterogeneity and clusters of conditions into consideration. The observational studies summarised involved patients with varied characteristics and from a wide range of settings contributing to substantial heterogeneity, which could affect the reliability of the findings. The use of cross-sectional design in almost all studies limits the ability to assess the outcome over a longer period and therefore makes it impossible to draw a causal relationship between the various determinants and multimorbidity.85 In the absence of intervention studies, the meta-analysis of the observational studies provides insight into the direction and strength of the association between the various risk factors and NCD multimorbidity. We did not include MeSH terms related to metabolic diseases such as obesity/overweight, metabolic syndrome and osteoarthritis mainly because they are risk factors of major NCDs. We believe, however, that our search strategy was able to cover these risk factors since most of the major NCDs are assessed together with these in most multimorbidity studies.

Implications of findings

The rising burden of multimorbidity in LMICs indicates the urgent need to strengthen the healthcare system to accommodate for the diagnosis and management of multiple chronic conditions. Available evidence shows that patients with multimorbidity have significantly higher mean outpatient and inpatient visits, resulting in higher out-of-pocket expenditure.9 43 58 Increased healthcare utilisation among patients with multimorbidity poses challenges to the patients, health providers and the healthcare system.

Evidence from HIC shows diverse challenges when dealing with patients with multimorbidity, including the complexity of multiple guidelines which focus on the management of single conditions and challenges in delivering patient-centred care.86 This emphasises the need to develop context-specific guidelines on how to diagnose and deal with multiple chronic conditions and to ensure better health service provision, health management and resource deployment to manage the increasing number of people with multimorbidity. Exploring the economic burden of multimorbidity across different settings and populations in LMICs will be crucial in informing policy decisions about service provision and resource allocation.

Despite the clear rise of multimorbidity in LMICs, there is a challenge in explaining the factors behind this rising burden given inconsistencies in findings. This is partly due to the lack of longitudinal studies providing strong evidence on the determinants and the differences in patterns of multimorbidity among different age groups as well as factors that influence variation in clusters of multimorbidity. The acceptance of a standard definition of multimorbidity will provide more clarity on the burden and epidemiology of multimorbidity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review shows a high burden of multimorbidity in LMICs, especially among women, the people who are well-off, and people residing in urban areas, with cardiometabolic and cardiorespiratory profiles being the most prevalent patterns of multimorbidity. There are however major gaps in epidemiological research on this topic, including the need for longitudinal data to access the true direction of the multimorbidity and its determinants, to establish causation and to identify how trends and patterns change over time.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @DanBoat98, @amarzafl

Contributors: OAA, AMF, DB and KK-G conceptualised the study. OAA and AMF carried out the literature search, data extraction and risk of bias assessment with support from DB. DB and OAA conducted the narrative synthesis and statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors (OAA, DB, AMF, SP, NL, JvO and KK-G) critically reviewed and approved the manuscript. DB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author (d.boateng-2@umcutrecht.nl).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Riley JC. The timing and pace of health transitions around the world. Popul Dev Rev 2005;31:741–64. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00096.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendoza W, Miranda JJ. Global shifts in cardiovascular disease, the epidemiologic transition, and other contributing factors: toward a new practice of global health cardiology. Cardiol Clin 2017;35:1–12. 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCD Alliance . Ncd facts: the global epidemic, 2017. Available: https://ncdalliance.org/the-global-epidemic [Accessed 26 Feb 2020].

- 4.Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya U, Jain K, et al. The impact of multimorbidity on adult physical and mental health in low- and middle-income countries: what does the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) reveal? BMC Med 2015;13:178. 10.1186/s12916-015-0402-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei MY, Mukamal KJ, Multimorbidity MKJ. Multimorbidity, mortality, and long-term physical functioning in 3 prospective cohorts of community-dwelling adults. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:103–12. 10.1093/aje/kwx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abebe F, Schneider M, Asrat B, et al. Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. J Comorb 2020;10:2235042X2096191–2096191. 10.1177/2235042X20961919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Flaherty M, Buchan I, Capewell S. Contributions of treatment and lifestyle to declining CVD mortality: why have CVD mortality rates declined so much since the 1960s? Heart 2013;99:159–62. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Academy of Medical Sciences . Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research, 2018. Available: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/82222577

- 9.Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, et al. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127199. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, et al. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet 2017;389:951–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30402-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornicroft G, Ahuja S, Barber S, et al. Integrated care for people with long-term mental and physical health conditions in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:174–86. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang HHX, Wang JJ, Wong SYS, Wong M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in China and implications for the healthcare system: cross-sectional survey among 162,464 community household residents in southern China. BMC Med 2014;12:188. 10.1186/s12916-014-0188-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palladino R, Tayu Lee J, Ashworth M, et al. Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilisation and health status: evidence from 16 European countries. Age Ageing 2016;45:431–5. 10.1093/ageing/afw044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, et al. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e297-307. 10.3399/bjgp12X636146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidalgo CA, Blumm N, Barabási A-L, et al. A dynamic network approach for the study of human phenotypes. PLoS Comput Biol 2009;5:e1000353. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afshar S, Roderick PJ, Kowal P. Global patterns of multimorbidity: a comparison of 28 countries using the world health surveys. In: Hoque M, Pecotte B, McGehee M, eds. Applied demography and public health in the 21st century. Cham: Springer, 2017: 381–402. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The World Bank . World bank country and lending groups – world bank data help desk. World Bank, 2019: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute . Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. National Institutes of health, department of health and human services, 2014. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 20.Higgins JP, Green S. Guide to the contents of a cochrane protocol and review. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Book Series, 2008: 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2000;19:3127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Altman DG, JAS on behalf of the CSMG and the CBMG . Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Julian PT, Higgins DGA, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Book Series, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses testing for heterogeneity. BMJ 2003. doi:10.1136%2Fbmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace BC, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. End-Users : R as a Computational Back-End 2012;49:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT. Commentary: heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1158–60. 10.1093/ije/dyn204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao J, Chua K-C, Prina M, et al. Multimorbidity and care dependence in older adults: a longitudinal analysis of findings from the 10/66 study. BMC Public Health 2019;19:585. 10.1186/s12889-019-6961-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agrawal S, Agrawal PK. Association between body mass index and prevalence of multimorbidity in Low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. Int J Med Public Health 2016;6:73–83. 10.5530/ijmedph.2016.2.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:205–14. 10.1093/gerona/glv128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christian AK, Sanuade OA, Okyere MA, et al. Social capital is associated with improved subjective well-being of older adults with chronic non-communicable disease in six low- and middle-income countries. Global Health 2020;16:2. 10.1186/s12992-019-0538-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou C-H, Tang S-F, Wang X-H, et al. Satisfaction about patient-centeredness and healthcare system among patients with chronic multimorbidity. Curr Med Sci 2018;38:184–90. 10.1007/s11596-018-1863-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunna R, San Sebastian M, Stewart Williams J. Measurement and decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in single and multimorbidity in older adults in China and Ghana: results from the who study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE). Int J Equity Health 2017;16:79. 10.1186/s12939-017-0578-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahimoghli R, Janati A, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in Iran: an investigation of a large pharmacy claims database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2020;29:39–47. 10.1002/pds.4925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hien H, Berthé A, Drabo MK, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly in Burkina Faso: cross-sectional study. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:1328–33. 10.1111/tmi.12377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunes BP, Chiavegatto Filho ADP, Pati S, et al. Contextual and individual inequalities of multimorbidity in Brazilian adults: a cross-sectional national-based study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015885. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rzewuska M, de Azevedo-Marques JM, Coxon D, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity within the Brazilian adult general population: evidence from the 2013 National health survey (PNS 2013). PLoS One 2017;12:e0171813. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Multimorbidity in chronic conditions: public primary care patients in four greater Mekong countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14. 10.3390/ijerph14091019. [Epub ahead of print: 06 09 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar P, Kumar S. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in an industrial city of eastern India. Indian J Psychiatry 2019;61:S474. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Islas-Granillo H, Medina-Solís CE, de Lourdes Márquez-Corona M, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in subjects aged ≥60 years in a developing country. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:1129–33. 10.2147/CIA.S154418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pati S, Swain S, Knottnerus JA, et al. Health related quality of life in multimorbidity: a primary-care based study from Odisha, India. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2019;17:116. 10.1186/s12955-019-1180-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunes BP, Thumé E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity in older adults: magnitude and challenges for the Brazilian health system. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1172. 10.1186/s12889-015-2505-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nugraha S, Hapsari I, et al. Multimorbidity increases the risk of falling among Indonesian elderly living in community Dwelling and elderly home: a cross sectional study. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2019;10:2263. 10.5958/0976-5506.2019.03898.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jovic D, Vukovic D, Marinkovic J. Prevalence and patterns of Multi-Morbidity in Serbian adults: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148646. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jankovic J, Mirkovic M, Jovic-Vranes A, et al. Association between non-communicable disease multimorbidity and health care utilization in a middle-income country: population-based study. Public Health 2018;155:35–42. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sum G, Salisbury C, Koh GC-H, et al. Implications of multimorbidity patterns on health care utilisation and quality of life in middle-income countries: cross-sectional analysis. J Glob Health 2019;9:20413. 10.7189/jogh.09.020413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan N, Rahman M, Mitra D, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity among Bangladeshi adult population: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030886. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jerliu N, Toçi E, Burazeri G, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic correlates of chronic morbidity among elderly people in Kosovo: a population-based survey. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:22. 10.1186/1471-2318-13-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar D, Raithatha SJ, Gupta S, et al. Burden of self-reported noncommunicable diseases in 26 villages of Anand district of Gujarat, India. Int J Chronic Dis 2015;2015:260143. 10.1155/2015/260143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khanam MA, Streatfield PK, Kabir ZN, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among elderly people in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr;29:406–14. 10.3329/jhpn.v29i4.8458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vancampfort D, Smith L, Stubbs B, et al. Associations between active travel and physical multi-morbidity in six low- and middle-income countries among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203277. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mini GK, Thankappan KR. Pattern, correlates and implications of non-communicable disease multimorbidity among older adults in selected Indian states: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013529. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rehr M, Shoaib M, Ellithy S, et al. Prevalence of non-communicable diseases and access to care among non-cAMP Syrian refugees in northern Jordan. Confl Health 2018;12:33. 10.1186/s13031-018-0168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phaswana-Mafuya N, Peltzer K, Chirinda W, et al. Self-reported prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases and associated factors among older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action 2013;6:20936. 10.3402/gha.v6i0.20936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Price AJ, Crampin AC, Amberbir A, et al. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and cascade of care in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural and urban Malawi. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:208–22. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30432-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aye SKK, Hlaing HH, Htay SS, et al. Multimorbidity and health seeking behaviours among older people in Myanmar: a community survey. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219543. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jawed M, Inam S, Shah N, et al. Association of obesity measures and multimorbidity in Pakistan: findings from the impact study. Public Health 2020;180:51–6. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vadrevu L. Rising challenge of multiple morbidities among the rural poor in India — a case of the Sundarbans in West Bengal. Int J Med Sci Public Heal 2016;5:343–50. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen H, Cheng M, Zhuang Y, et al. Multimorbidity among middle-aged and older persons in urban China: prevalence, characteristics and health service utilization. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2018;18:1447–52. 10.1111/ggi.13510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pati S, Agrawal S, Swain S, et al. Non communicable disease multimorbidity and associated health care utilization and expenditures in India: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:451. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, Multi-Country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:205–14. 10.1093/gerona/glv128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woldesemayat EM, Kassa A, Gari T, et al. Chronic diseases multi-morbidity among adult patients at Hawassa university comprehensive specialized Hospital. BMC Public Health 2018;18:352. 10.1186/s12889-018-5264-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pati S, Swain S, Hussain MA, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of multimorbidity in South Asia: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007235. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One 2014;9:e102149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, et al. Do men consult less than women? an analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003320. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santosh J, Crampton P. Gender differences in general practice utilisation in New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 2009;1:261–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eichener A, Robbins G. National snapshot: poverty among women & families. Fact sheets, 2014. Available: https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Poverty-Snapshot-Factsheet-2017.pdf [Accessed 14 Aug 2021].

- 67.Allen L, Williams J, Townsend N, et al. Socioeconomic status and non-communicable disease behavioural risk factors in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e277–89. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30058-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson NW, Couper ID, De Vries E, et al. A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1060. 10.22605/RRH1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Sayed AM, Vail D, Kruk ME. Ineffective insurance in lower and middle income countries is an obstacle to universal health coverage. J Glob Health 2018;8:020402. 10.7189/jogh.08.020402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gopichandran V, Jayamani V, Lee P, et al. Diet and physical activity among women in urban and rural areas in South India: a community based comparative survey. J Family Med Prim Care 2013;2:334. 10.4103/2249-4863.123782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Assah FK, Ekelund U, Brage S, et al. Urbanization, physical activity, and metabolic health in sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Care 2011;34:491–6. 10.2337/dc10-0990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carter P, Lagan J, Fortune C, et al. Association of cardiovascular disease with respiratory disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2166–77. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Health effects of cigarette smoking, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schäfer I, von Leitner E-C, Schön G, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS One 2010;5:e15941. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Calderón-Larrañaga A, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in primary care: interactions among chronic diseases using factor analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e32190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, et al. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature 2007;450:494–6. 10.1038/450494a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the world health surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mujica-Mota RE, Roberts M, Abel G, et al. Common patterns of morbidity and multi-morbidity and their impact on health-related quality of life: evidence from a national survey. Qual Life Res 2015;24:909–18. 10.1007/s11136-014-0820-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gallo JJ, Hwang S, Joo JH, et al. Multimorbidity, depression, and mortality in primary care: randomized clinical trial of an evidence-based depression care management program on mortality risk. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:380–6. 10.1007/s11606-015-3524-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Psychological distress and multimorbidity in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:417–22. 10.1370/afm.528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Panagioti M, Stokes J, Esmail A, et al. Multimorbidity and patient safety incidents in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135947. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patel V, Chatterji S. Integrating mental health in care for noncommunicable diseases: an imperative for person-centered care. Health Aff 2015;34:1498–505. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.SC W, CY L, DS K. The agreement between self-reporting and clinical diagnosis for selected medical conditions among the elderly in Taiwan. Public Health. 10.1016/s0033-3506(00)00323-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, et al. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1407–17. 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levin KA. Study design III: cross-sectional studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7:24–5. 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sinnott C, Mc Hugh S, Browne J, et al. GPs’ perspectives on the management of patients with multimorbidity: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003610. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koyanagi A, Lara E, Stubbs B, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity, and mild cognitive impairment in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:721–7. 10.1111/jgs.15288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A. Physical chronic conditions, multimorbidity and sedentary behavior amongst middle-aged and older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:147. 10.1186/s12966-017-0602-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Firth J, et al. Handgrip strength, chronic physical conditions and physical multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults in six low- and middle income countries. Eur J Intern Med 2019;61:96–102. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Waterhouse P, van der Wielen N, Banda PC, et al. The impact of multi-morbidity on disability among older adults in South Africa: do hypertension and socio-demographic characteristics matter? Int J Equity Health 2017;16:62. 10.1186/s12939-017-0537-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049133supp001.pdf (76.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp002.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp003.pdf (121.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp006.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp007.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp004.pdf (112.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp005.pdf (204.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049133supp008.pdf (105.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author (d.boateng-2@umcutrecht.nl).