Abstract

Clinical findings in 36 immunosuppressed patients with lower respiratory tract infection or bacteremia with Actinobacillus hominis are described. Animal contact was only recorded for three patients; nine patients died despite appropriate antimicrobial treatment. Although infections with this microorganism seem to be rare, the fact that 37 of 46 strains characterized in this study have been found in Copenhagen indicates that under-reporting may occur. A. hominis is phenotypically relatively homogeneous but can be difficult to differentiate from other Actinobacillus species unless extensive biochemical testing is performed. Mannose-positive strains of A. hominis are especially difficult to differentiate from A. equuli. Attempts to identify A. hominis by automatic identification systems may lead to misidentifications. Ribotyping and DNA-DNA hybridization data show that A. hominis is a homogeneous species clearly separated from other species within the genus Actinobacillus.

The genus Actinobacillus is comprised of species that are animal pathogens, the only exceptions being Actinobacillus ureae and Actinobacillus hominis, which appear to be highly adapted to humans. A. ureae was first described as a human respiratory tract pathogen in 1960 (8). In 1981, Friis-Møller reported on 17 cases of respiratory tract infections with an “A. ureae-like” bacterium, which was classified as a distinct species, A. hominis (5). Since then, only a few reports of diseases caused by this microorganism have been reported in the literature; these have, however, involved invasive disease (6, 12).

Since we now have a collection of 46 A. hominis strains isolated from various European countries, including blood culture isolates, we report here on clinical findings from patients infected with this microorganism. Furthermore, we investigate strain variability within A. hominis and describe its relationship to closely related species of the family Pasteurellaceae as determined by conventional methods, ribotyping, and DNA-DNA hybridization, and we examine the accuracy of commercial identification systems in this area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The 46 A. hominis isolates examined in the present study are listed in Table 1. Thirty-eight isolates from 37 patients (one patient had A. hominis isolated twice from the sputum with an interval of 15 months) were found in Copenhagen at five different departments of clinical microbiology from 1977 to 1999. There were two isolates each from Greenland, Germany, and France and one each from the Czech Republic and Sweden. The majority of isolates were found in the respiratory tract (sputa and tracheal and bronchial secretions), one was from the pleural fluid, and four were from blood. Selected strains were studied for DNA-DNA hybridization levels and were characterized by automatic identification systems (vide infra). Twenty type and reference strains from taxa related to A. hominis and used for comparison in the bacteriological study are listed in Table 2. Of these, only the Haemophilus species and A. ureae are indigenous species in man.

TABLE 1.

A. hominis isolates examined in this study (n = 46)

| Strain designation(s)

|

Source (yr) of isolation | |

|---|---|---|

| This study | Other designationsa | |

| 1 to 35b | NCTC 11529T, CCUG 23130+, CCUG 11625, SSI P1530, and all AFM isolates except AFM 54 | Lower respiratory tract; Copenhagen (1977–1995) |

| AFM 54 | Pleural fluid; Copenhagen (1986) | |

| SSI P1587 and SSI P1591 | Blood; Copenhagen (1999) | |

| SSI P851 and SSI P1336 | Lower respiratory tract; Greenland (1984 and 1990) | |

| CCUG 23131 | MCCM 00414 | Lower respiratory tract; Hamburg (1984) |

| CCUG 23129 | MCCM 00432 | Blood; Stuttgart (1987) |

| CCUG 25843 | Nasopharynx; Stockholm (1989) | |

| CCUG 37044 | SSI P1284 | Lower respiratory tract; E. Aldova, Prague (1988) |

| SSI P1592 | Blood; E. Heurtin, Rennes (1999) | |

| SSI P1593 | Lower respiratory tract; E. Heurtin, Rennes (1999) | |

NCTC, National Collection of Type Cultures, London, England; CCUG, Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Sweden; SSI, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark; MCCM, Medical Culture Collection Marburg, Philips University, Marburg, Germany.

The 35 isolates derived from 34 patients (see text).

TABLE 2.

A. hominis-related taxa examined in this study (n = 20)

| Organism | Strain designation(s)a |

|---|---|

| Actinobacillus capsulatusb | NCTC 11408T, SSI P243 |

| Actinobacillus equulib | NCTC 8529T, SSI P157 |

| Actinobacillus equuli | SSI P238 |

| Actinobacillus lignieresiib | NCTC 4189T, SSI P151 |

| Actinobacillus murisb | CCUG 16938T, SSI P1573 |

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniaeb | ATCC 27088T, SVS 4074 S1 |

| Actinobacillus suisb | ATCC 33415T, CCM 5586, SSI P635 |

| Actinobacillus ureaeb | NCTC 10219T, SSI P161 |

| Actinobacillus ureae | SSI P644 |

| Pasteurella pneumotropica, Jawetzb | NCTC 8141T, SSI P421 |

| Pasteurella pneumotropica, Hey(-)lb | ATCC 12555, SSI P309 |

| Bisgaard taxon 8b | CCUG 16494, SSI P1572 |

| Bisgaard taxon 9b | CCUG 15571, SSI P1575 |

| Bisgaard taxon 11b | CCUG 15573, SSI P1577 |

| Haemophilus haemolyticus | NCTC 10659T, HK 386, SSI P1579 |

| Haemophilus haemolyticus | HK 676 |

| Haemophilus parahaemolyticus | NCTC 8479T, HK 385 |

| Haemophilus paraphrohaemolyticus | SSI P1300 |

| Haemophilus paraphrohaemolyticus | NCTC 10670T, HK 411 |

| Haemophilus segnis | ATCC 33393T, HK 316 |

CCM, Czechoslovak Collection of Microorganisms, Prague, Czech Republic; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.; SSI, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark; SVS, Statens Veterinaere Serumlaboratorium, Copenhagen, Denmark; NCTC, National Collection of Type Cultures, London, England; CCUG, Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Sweden; HK, M. Kilian, Aarhus, Denmark.

Strains tentatively characterized by automatic identification systems.

Clinical study.

Patient records from 36 of the 37 Danish patients with A. hominis were studied as soon as the microorganisms were identified. Demographic data, including employment and animal contact history, underlying disease, and predisposing conditions, as well as symptoms and signs, were recorded.

Phenotypic characterization.

All of the strains studied were characterized by conventional tests as described previously (5). A total of 13 representative A. hominis strains and the 12 type and reference strains not belonging to the genus Haemophilus (see Table 2) were tentatively characterized by two commercial, automatic identification systems, ID 32E and Vitek GNI+ (both from bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Of the Pasteurellaceae, Pasteurella multocida and Pasteurella haemolytica are included in the database of both systems. Furthermore, ID 32E includes Pasteurella pneumotropica, and Vitek GNI+ includes A. ureae. Readings of the ID 32E system were done at both 24 and 48 h; when no profiles were produced automatically due to a questionable test result, this was resolved by visual reading. Only identifications accompanied by the epithets “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” or “acceptable” were considered to be definitively identified.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was done with Neo-Sensitabs (Rosco, Taastrup, Denmark) on Danish blood agar (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Ribotyping.

Riboprinting was performed using the RiboPrinter System, as recommended by the manufacturer (Qualicon, Wilmington, Del.). In brief, single colonies from a 24-h culture on a 5% blood agar plate were suspended in a sample buffer and heated at 80°C for 15 min. After the addition of lytic enzymes, samples were transferred to the RiboPrinter System. Further analysis, including HindIII restriction of DNA, was carried out automatically. The riboprint profiles were aligned according to the position of a molecular size standard and compared with patterns obtained previously. Profiles were analysed with the BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Similarity calculations were based on Dice coefficient and dendrograms generated by UPGMA clustering to determine profile relatedness.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

DNA was extracted from 21 strains of A. hominis, including the type strain, and from reference strains of 12 related taxa, as described by Gerner-Smidt (7) with modifications. Prior to lysis, the suspension of bacteria was treated with RNase in addition to lysozyme. After the purified DNA was pelleted by centrifugation, it was washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and dissolved in distilled water. For each strain, 5 to 10 tubes were processed. The purity of the DNA was determined spectrophotometrically. Ten strains (A. hominis and non-A. hominis strains) were extracted thrice and in connection with the second extraction treated with RNase, protease, and perchlorate. The DNA was sonicated, and the phosphate buffer concentration was adjusted to 0.28 M.

The method used for the determination of the degree of DNA relatedness, i.e., relative binding ratio, was the hydroxyapatite hybridization method of Brenner et al. (1); the degree of relatedness is expressed as a percentage. The DNAs were labeled enzymatically in vitro with [32P]dCTP using a nick translation reagent kit (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). DNA hybridization experiments were performed at 55°C for optimal DNA reassociation and at 70°C for stringent DNA reassociation. The percentages of divergence within related sequences were determined by assuming that each degree of DNA heteroduplex instability, compared with the melting temperature of the homologous DNA duplex, was caused by approximately 1% of unpaired bases. Before normalization to 100%, the levels of DNA bound to hydroxyapatite in homologous reactions were 51 to 72%. The levels of labeled DNA that bound to hydroxyapatite in control reaction mixtures that did not contain unlabeled DNA were 1 to 2.5% at 55°C and 1 to 3% at 70°C. Enhancing the extraction procedure (three extractions) elevated the level of DNA bound in homologous reaction from 51 to 72%.

RESULTS

Clinical study.

Of the 36 patients for whom records were available, 6 were women and 30 were men. Their ages ranged from 19 to 80 years. All of the patients had underlying diseases or other predisposing conditions for infections (Table 3) and were from low socioeconomic groups. Animal contact was only recorded for three patients. Upon admission to hospital, all patients were in a poor general condition and suffering from severe respiratory insufficiency, including two patients with A. hominis bacteremia and one with a pleural empyema. The majority of patients had low-grade fever and pulmonary infiltrates, although distinction between old and new infiltrates was not always possible. Nine of the patients, including one with bacteremia, died despite appropriate antimicrobial treatment with penicillin or ampicillin.

TABLE 3.

Underlying diseases and other predisposing factors in 36 patients with A. hominis infectiona

| Underlying disease or predisposing factor | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Chronic alcoholism | 17 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 11 |

| Drug addiction and/or psychiatric disorders | 10 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 10 |

| Pulmonary or esophageal cancer | 7 |

| Hepatitis or liver cirrhosis | 6 |

| Tuberculosis vetus | 4 |

| Cerebral malaria | 1 |

A total of 23 patients suffered from more than one predisposing factor.

Of 36 patients, 28 had not received antimicrobial treatment prior to microbiological sampling. A. hominis was isolated in pure culture from the blood of 2 patients, the pleural fluid of 1 patient, and lower respiratory tract specimens of 18 patients. In the remaining 15 respiratory tract specimens, A. hominis was cultured together with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Conventional tests.

The 46 A. hominis strains grew with grayish-white, mucoid and nonmucoid, soft colonies of about 1 to 2 mm in diameter without hemolysis on 5% horse blood agar after 24 h of incubation. In semisolid agar, the strains grew facultatively anaerobically and were nonmotile. The strains grew very poorly or not at all on bromothymol blue (modified Conradi-Drigalski) agar. The Gram stain showed small, pleomorphic gram-negative rods, often with a vacuolated appearance. Mucoid colonies consisted of bacteria with a small capsule. The biochemical reactions of the A. hominis strains are shown together with reactions of the 12 type and reference strains of the closely related taxa (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of A. hominis and type and reference strains of related taxa

| Characteristic | Resultsa with:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. hominis (46 strains) | A. capsulatus NCTC 11408T | A. equuli NCTC 8529T | A. lignieresii NCTC 4189T | A. muris CCUG 16938T | A. pleuropneumoniae ATCC 27088T | A. suis CCM 5586T | A. ureae NCTC 10219T | Bisgaard taxon 8 CCUG 16494 | Bisgaard taxon 9 CCUG 15571 | Bisgaard taxon 11 CCUG 15573 | P. pneu- motropica (Jawetz) NCTC 8141T | P. pneumotropica (Heyl) ATCC 12555 | |

| Hemolysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| Oxidase production | + | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + |

| Urease production | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| β-Galactosidase (ONPG) production | 45/46 | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + |

| β-Glucuronidase (PGUA) production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indole production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| Nitrate reduction | 23/23 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nitrite reduction | 23/23 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + |

| Gelatinase production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arginine production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lysine production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Ornithine production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| Acid production | |||||||||||||

| l-Arabinose | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| d-Xylose | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + |

| l-Rhamnose | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| d-Glucoseb | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| d-Galactose | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| d-Mannose | 9/46 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sucrose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lactose | 45/46 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + |

| Maltose | 45/46 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cellobiose | 2/46 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Trehalose | + | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| Melibiose | 44/46 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + |

| Adonitol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dulcitol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| d-Sorbitol | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| d-Mannitol | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inositol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Salicin | 23/46 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Esculin | 15/46 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Raffinose | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + |

0, negative; +, positive.

No gas produced from glucose by any strains.

ID 32E.

Characterization of 13 A. hominis strains resulted in 10 different profiles at 24 h. Eight of these profiles resulted in the epithet “doubtful profile” and were thus considered to be unidentified. The last two profiles resulted in an “acceptable identification” of Ochrobactrum anthropi (percent identification = 88.0, T = 0.60) for two strains and an “acceptable identification” of P. pneumotropica (percent identification = 89.2, T = 88.0) for one strain. Different results of carbohydrate fermentation were the cause of the different profiles.

For the 12 strains representing the taxa related to A. hominis, 10 different profiles were generated after 24 h. Six profiles from six strains were interpreted as giving no identification, while the two strains of P. pneumotropica were correctly identified with the epithets “acceptable” and “good” identification. The last four strains (A. equuli, A. lignieresii, and Bisgaard taxa 8 and 9) were misidentified as P. pneumotropica by two different profiles.

Vitek.

Ten bionumbers were produced for the 13 A. hominis strains with this system. Nine strains comprising six bionumbers were labeled as unidentified at 12 h. Four strains were identified as A. ureae, with normalized probability percentages of 99, 97, and 93% at 8, 8, and 4 h, respectively; the last strain was identified with a normalized probability percentage of 77% at 12 h, with the additional comment “good confidence, marginal separation.”

From the 12 strains representing taxa related to A. hominis, eight bionumbers were produced. A. suis and A. pleuropneumoniae were unidentified at 12 h, while the A. ureae strain was correctly identified at 12 h with a normalized probability percentage of 76% and the comment “good confidence, marginal separation.” The type strain of P. pneumotropica was misidentified as 99% Vibrio alginolyticus at 7 h, and Bisgaard taxon 11 was misidentified as 99% Sphingobacterium multivorum at 12 h. The remaining seven strains were misidentified as A. ureae with probability percentages of ≥93%.

Antibiotic susceptibility.

The A. hominis strains were found to be sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and polymyxin by the tablet diffusion method.

Ribotyping.

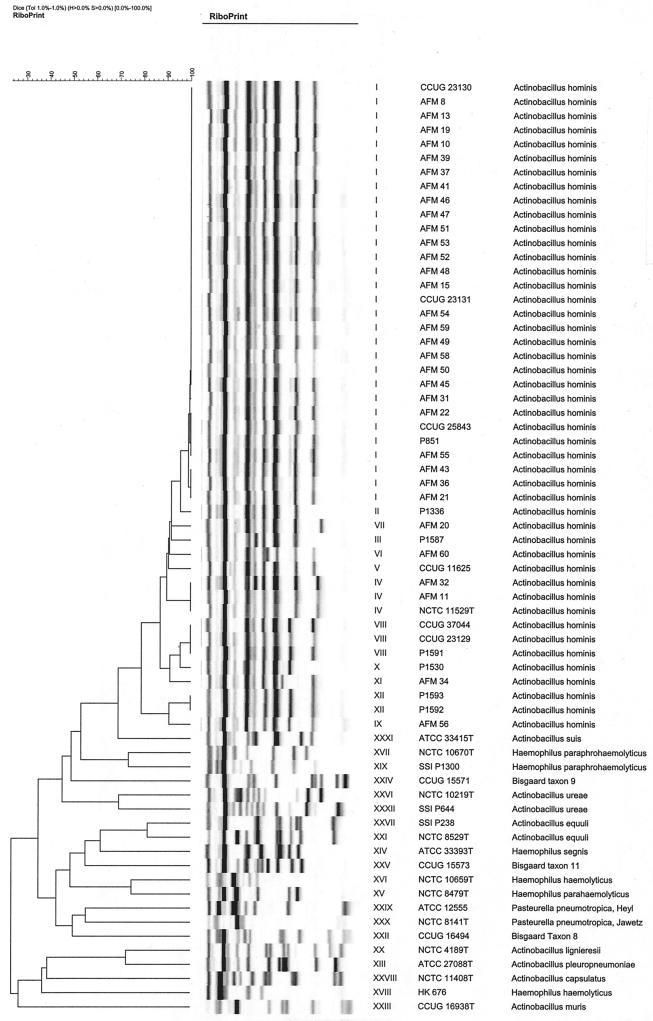

By schematic presentation of the riboprints in a dendrogram (Fig. 1), all 46 isolates of A. hominis were easily differentiated from the 20 strains of the related taxa. The A. hominis isolates could be divided into 12 different ribogroups, of which one (ribogroup I) consisted of the majority (n = 30) of the isolates. Three smaller ribogroups (IV, VIII, and XII) included two to three isolates each, while the remaining eight ribogroups were represented by only one strain each. Group I consisted of 27 Danish strains plus one strain from Germany (CCUG 23131), one strain from Greenland (P851), and the Swedish strain (CCUG 25843). Group IV comprised the type strain and two other Danish strains; group VIII comprised the other German strain (CCUG 23129), the Czech strain (CCUG 37044), and a Danish strain; and group XII comprised the two French strains (P1592 and P1593) from two different patients from the same microbiology laboratory. The four blood culture isolates belonged to three different ribogroups (III, VIII, and XII). For the 20 strains from the related taxa, each species or taxon was assigned to unique ribogroups. Two strains each of A. ureae, A. equuli, and H. paraphrohaemolyticus, clustered together, whereas the two strains of H. haemolyticus were not related as determined by riboprinting.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of schematic presentation of the riboprints of 46 strains of A. hominis and 20 type and reference strains of related taxa.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

The type strain of A. hominis was radiolabeled for use in DNA reassociation experiments, and the relatedness to 20 strains of A. hominis (including two mannose-fermenting strains) was determined. The strains were closely related, exhibiting 89 to 100% (median, 96%) relatedness at 55°C (optimal temperature) and 83 to 99% (median, 94%) relatedness at 70°C (stringent temperature), and the percentage of divergence (%D) was 0 to 1.2%, except for one strain having a %D of 4.1%. The results obtained in DNA reassociation experiments between the type strain of A. hominis and related organisms are given in Table 5. Of the 12 related taxons examined in this study, 10 had relative binding ratio (RBR) values of <70% at 55°C, although the A. equuli strain, the A. suis strain, and the A. capsulatus strain had RBR values of between 64 and 69%. Two strains, A. ureae and A. pleuropneumoniae, had RBR values of 70%, but %D values of 5.3 and 7.1%, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Relatedness of the type strain of A. hominis and related organisms

| Source of unlabeled DNA | RBR (% relatedness) at 55°C |

|---|---|

| Actinobacillus capsulatus NCTC 11408T | 64 |

| Actinobacillus equuli NCTC 8529T | 68 |

| Actinobacillus lignieresii NCTC 4189T | 50 |

| Actinobacillus muris CCUG 16938T | 24 |

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae ATCC 27088T | 75 (%D = 7.1) |

| Actinobacillus suis ATCC 33415T | 68 |

| Actinobacillus ureae NCTC 10219T | 70 (%D = 5.3) |

| Pasteurella pneumotropica (Jawetz) NCTC 8141T | 19 |

| Pasteurella pneumotropica (Heyl) ATCC 12555 | 20 |

| Bisgaard taxon 8 CCUG 16494 | 38 |

| Bisgaard taxon 9 CCUG 15571 | 50 |

| Haemophilus parahaemolyticus NCTC 8479T | 29 |

DISCUSSION

Except for the present study and its predecessor, whose patients all are included in the present material (5), very few cases with presumed or confirmed A. hominis infection have been described previously. In 1971, Rolland and Vandepitte (10) described eight patients with P. ureae pneumonia; one of the involved strains, which has not been preserved, appears from the description to be more compatible with A. hominis than with A. ureae based on the ability to ferment xylose, lactose, and salicin. A case of pleural empyema with A. hominis in a patient with carcinoma was published in 1988 (6). Finally, in 1991 Wüst et al. (12) reported two cases of bacteremia with A. hominis in patients with hepatic failure and a history of drug and alcohol abuse. Both patients died despite appropriate antimicrobial treatment. Autopsy was performed in one patient and disclosed necrotizing purulent bronchopneumonia. These cases are in agreement with our own findings, including the two cases of bacteremia, regarding predisposing factors, poor general condition of the patients, and the respiratory tract as the primary infectious focus.

Why A. hominis mainly has been isolated in Copenhagen is not clear. The fact that A. hominis has been described from bacteremias in Switzerland (12), Germany (12), and France (the present study) and has been isolated from respiratory tract specimens from Greenland, Sweden, and the Czech Republic indicates that the geographic dissemination of the microorganisms is widespread. A tradition for extensive characterization of small gram-negative rods in this country is probably part of the explanation for the predominance of the Danish isolates. Another explanation may be a rather intensive microbiology service in Copenhagen during the period involved.

Phenotypically, A. hominis is seen to be a relatively homogeneous taxon, but the mannose-positive strains (19%) may be difficult to differentiate from A. equuli (Table 4). However, these strains were, with two exceptions, salicin positive, a trait not compatible with A. equuli, and their colony morphology and riboprints were characteristic for A. hominis. One A. hominis bacteremia strain (P1591) was β-galactosidase negative, making A. ureae a possible diagnosis. The carbohydrate pattern (Table 4) and riboprint (Fig. 1), however, identified the strain clearly as A. hominis.

Automatic identification systems obviously play increasingly important roles in routine clinical microbiology. However, it should be equally obvious that the manufacturers are responsible for providing the user with information regarding the limitations of the systems. The majority of the attempts at identification of the 13 A. hominis strains resulted in doubtful profiles (ID 32E) or no identifications (Vitek), which is quite satisfactory, since A. hominis is not included in the databases of the systems. Misidentification as members of the family Pasteurellaceae (ID 32E, P. pneumotropica; Vitek, A. ureae) may be tolerable, but misidentification as O. anthropi with the epithet acceptable identification for two strains is not. Likewise, it may be tolerable when 4 of 12 strains representing the taxa related to A. hominis are misidentified as P. pneumotropica (ID 32E), but it is unsatisfactory when 2 of 12 strains are misidentified as V. alginolyticus and S. multivorum, respectively, with identification percentages of 99 (Vitek).

Riboprinting clearly discriminated all A. hominis strains from the related taxa included in this study. By adding the A. hominis ribogroups to the identification database of the RiboPrinter these riboprints can be used in future identification of presumptive A. hominis strains. Unknown isolates exhibiting a similarity of more than 84% to these ribogroups will result in species identification as A. hominis. Using this system for identification of A. hominis seems to be a valuable tool in identification.

According to the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics, the definition of a species would generally include strains with 70% or greater DNA- DNA relatedness under optimal conditions and a %D value of <5% for related sequences (11). All A. hominis strains examined in this study fulfilled these criteria. In the literature, two previous DNA relatedness studies have identified two and four A. hominis strains closely related to the type strain (2, 4). The level of relatedness found at 55°C between A. hominis DNA and DNAs of related species within the Actinobacillus genus was from 24 to 75% (Table 5). A. muris was the most distantly related and A. pleuropneumoniae was the most closely related, with the other Actinobacillus species placed in between these two. However, for the two Actinobacillus species most closely related to A. hominis, A. pleuropneumoniae and A. ureae, divergences of 7.1 and 5.3%, respectively, were found. In the literature, A. hominis DNA has been compared to DNA from A. ureae, A. equuli, A. lignieresii, P. pneumotropica, and P. multocida (2, 4). Results similar to those found in this study were reported for A. ureae, A. equuli, A. lignieresii, and P. pneumotropica, showing distant relatedness of A. hominis to P. pneumotropica but close relatedness to A. ureae and A. equuli. This is also in accordance with the 16S rRNA sequence data for single strains of each taxon published by Dewhirst et al (3). In this study, A. hominis fell into cluster 4A (genus Actinobacillus sensu stricto) together with A. equuli, A. lignieresii, A. pleuropneumoniae, A. suis, and A. ureae. Neighboring clusters contained A. muris, P. pneumotropica, A. capsulatus, and Bisgaard taxa 8 and 9.

In conclusion, A. hominis is associated with chronic, lower respiratory tract disease in debilitated patients and may cause bacteremia. Infections with this microorganism appear to be rare, but our findings suggest that under-reporting may take place. A. hominis is phenotypically homogeneous but may be difficult to differentiate from other Actinobacillus species, especially A. equuli, if the strain ferments mannose. However, genomic data from ribotyping, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing clearly demonstrate a distinct species within genus Actinobacillus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner D J, McWhorter A C, Knutson J K L, Steigerwalt A G. Escherichia vulneris: a new species of Enterobacteriaceae associated with human wounds. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1133–1140. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1133-1140.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christiansen C, Hansen E, Friis-Møller A. Homology between DNA from selected strains of the genera Pasteurella, Actinobacillus, and Haemophilus. In: Kilian M, Frederiksen W, Biberstein E L, editors. Haemophilus, Pasteurella and Actinobacillus. London, England: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewhirst F E, Paster B J, Olsen I, Fraser G J. Phylogeny of the Pasteurellaceae as determined by comparison of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid sequences. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1993;279:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80489-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert F, Stenzel A, Mutters R, Frederiksen W, Mannheim W. Some unusual members of the family Pasteurellaceae isolated from human sources—phenotypic features and genomic relationships. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1991;275:143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friis-Møller A. A new Actinobacillus species from the human respiratory tract. In: Kilian M, Frederiksen W, Biberstein E L, editors. Haemophilus, Pasteurella and Actinobacillus. London, England: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friis-Møller A, Kharazmi A. Neutrophil response, serum opsonic activity, and precipitating antibodies in human infection with Actinobacillus hominis. APMIS. 1988;96:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerner-Smidt P. Ribotyping of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2680–2685. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2680-2685.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksen S D, Jyssum K. A new variety of Pasteurella haemolytica from the human respiratory tract. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1960;50:433. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1960.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutters R, Frederiksen W, Mannheim W. Lack of evidence for the occurrence of Pasteurella ureae in rodents. Vet Microbiol. 1984;9:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(84)90081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolland A, Vandepitte J. Pasteurella ureae. Acta Clin Belg. 1971;26:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17843286.1971.11716765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wayne L G, Brenner D J, Colwell R R, Grimont P A D, Kandler O, Krichevsky M I, Moore L H, Moore W E C, Murray R G E, Stackebrandt E, Starr M P, Trüper H G. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:463–464. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wüst J, Gubler J, Mannheim W, von Graevenitz A. Actinobacillus hominis as a causative agent of septicemia in hepatic failure. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:693–694. doi: 10.1007/BF01975828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]