Abstract

Background

The associations between premature atherosclerosis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) are not fully investigated. To determine whether IMIDs are associated with premature atherosclerosis, we examined the risk of incident coronary artery disease (CAD) in men less than 45 years old and women less than 50 years old with various forms of IMIDs compared with general population.

Methods

A population-based cohort was established and included patients with IMID, who were followed until the development of CAD, withdrawal from the insurance system, death, or 31 December 2016, whichever point came first. Patients with IMID included rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), primary Sjogren’s syndrome (SjS), idiopathic inflammatory myositis, systemic sclerosis (SSc), Behcet’s disease (BD), and systemic vasculitis (SV). The comparison group was 1 000 000 beneficiaries sampled at random from the whole population as matched control participants. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the cumulative incidences of CAD in patients with and without IMID.

Results

Among 58 862 patients with IMID, 2139 (3.6%) developed CAD and 346 (1.3%) developed premature CAD. Relative to the comparison cohorts, the adjusted HRs for premature CAD were 1.43 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.86) for primary SjS, 2.85 (95% CI 2.63 to 3.43) for SLE, 3.18 (95% CI 1.99 to 5.09) for SSc and 2.27 (95% CI 1.01 to 5.07) for SV.

Conclusions

Primary Sjogren’s syndrome, SLE, SSc and SV are associated with an increased risk of premature CAD. Our findings will support essential efforts to improve awareness of IMID impacting young adults.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases, epidemiology

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Many immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) have significant links with atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), systemic sclerosis (SSc) and primary Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS).

What does this study add?

Using a population-based study in Taiwan from 2004 to 2016, we compared IMIDs to their comparisons and confirmed that patients with RA, SjS, SLE, idiopathic inflammatory myositis, and SSc have increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD).

Further, our study found an increase of 40% in the risk of incident premature CAD for SjS, a threefold increase for SLE, around a threefold rise for SSc, and a twofold rise in systemic vasculitis when set beside their respective comparisons.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

Our work clarifies that greater attention should be paid to at-risk groups in the younger population and our findings will support essential efforts to improve awareness of IMID impacting young adults.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major health problem in developed countries and potentially leads to lethal complication.1 2 Published studies reported elevating trends of premature CAD and significantly higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular (CV) risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus among young adults.3 4 However, the increased incidence of CAD in patients with rheumatic disease is independent of traditional CV risk factors.5 6 There is a growing agreement and recognition of the role played by innate and adaptive immune systems in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis.7 8 The chronic inflammatory response characterised by immune-mediated inflammatory disease (IMID) may also promote endothelial dysfunction6 9 and accelerate the development of atherogenesis,10–12 thus significantly contributing to morbidity and mortality.13 The significant link between IMID and atherosclerotic CV manifestations has been established.14 15 Previous research has described the association between CAD and certain forms of IMID, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA),10 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),16 systemic sclerosis (SSc)17 and primary Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS).18

A recent study observed a significantly higher prevalence of premature CAD in patients with SLE and RA compared with general population,19 and the prognosis of premature CAD is poorer when coexisting with inflammatory diseases and autoimmune disorders.20 21 Owing to the risk of disability and lifelong healthcare issues, the burden of CAD is especially significant in young populations. However, the risks of premature CAD in patients with other forms of IMID have not been fully investigated. Our study aims to clarify whether IMID is a risk factor for premature CAD.

Material and methods

Patients and data sources

Taiwan launched a single-payer National Health Insurance programme on 1 March 1995. As of 2014, 99.9% of Taiwan’s population are enrolled.22 The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) has been released to researchers in an electronically encrypted form since 1999 and the system’s registry of patient files for catastrophic illness was used to establish the cohort of IMIDs in our study. To meet support objectives regarding families faced with major illnesses and the associated financial burden, the NHI system specifies 31 categories of catastrophic illness, covering most IMIDs. No need to have particularly severe disease course. To obtain a catastrophic illness certificate (CIC), the attending physician of a patient diagnosed as falling into one such category of catastrophic illness is required to provide relevant clinical and laboratory information as part of the application for review. The review committee then assesses the application according to the classification criteria for each diagnosis, and if approved, patients are then exempted from copayment for IMID-related treatment.23 The large sample sizes and high quality of catastrophic illness-related diagnosis within the claims data help create a reliable data set suitable for estimation of premature CAD incidence among patients with IMID in its various forms. All data in this study were anonymous.

Definition of patients with IMID and premature CAD

The International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) was used for coding the diagnosis of the diseases relevant to our study. Our study used a retrospective, population-based cohort of patients in Taiwan with a diagnosis of IMID in one or more of the following forms: RA (ICD-9-CM 714.0), SLE (ICD-9-CM 710.0), SjS (ICD-9-CM 710.2), idiopathic inflammatory myositis (IIM) (ICD-9-CM 710.3 and 710.4), SSc (ICD-9-CM 710.1), Behcet’s disease (BD) (ICD-9-CM 136.1) and systemic vasculitis (SV) (ICD-9-CM 446); this cohort was confined to those aged ≧18 years between 2004 and 2016 who had been approved for the CIC as a result of their IMID.

We divided each IMID into the following categories: men under 45, women under 50 years of age; men over 45, women over 50 years of age; and all ages. We defined patients who developed CAD before 45 years for men and before 50 years for women as premature CAD. Outcomes were compared with patients who had no diagnosis of IMID. For solid outcome, incident CAD cases appearing in our study included acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (ICD-9-CM 410) and ischaemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM 411), these having been retrieved from the inpatient diagnosis claims data as the principal diagnosis. The validity of AMI diagnosis coding in the Taiwan NHIRD has been verified and the positive predictive value (PPV) for AMI was 0.88. The PPV increased to 0.93 when using only the principal diagnosis in the NHIRD.24 To avoid inclusion of high-risk patients, we estimated the risk of CAD only in patients with IMID who had no previous inpatient diagnosis for CAD (ICD-9-CM 410, 411, 412, 413, 414) 3 years prior to the diagnosis of their IMID.

Our comparison group was 1 000 000 beneficiaries sampled at random from the whole population as matched control participants. We randomly assigned an index date for each control group. To minimise selection bias, we applied identical selection criteria and only considered as potential candidates for the control group those who had complete information on age or sex, were aged ≥18 years between 2004 and 2016, and who had no history of CAD in the 3 years prior to the index date.

Study design

Our study spanned the period from 1 January 2004 through to 31 December 2016. With the IMID cohorts, follow-up commenced from the date of CIC issuance for IMID, this date also being matched for the comparison groups (as the index date). We excluded patients younger than 18 years, and those who had incomplete information on age or sex. During the follow-up period, we linked participants to the admission claims data to identify the first episode of CAD (ICD-9-CM code 410 or 411). From the date of cohort entry, all patients were followed until the development of CAD, withdrawal from the insurance system, death or 31 December 2016, whichever point came first.

Statistical analysis

Data processing and statistical analysis were performed using SAS statistical software (V.9.4.1; SAS Institute). Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate the HR of CAD for individual IMID compared with the control group. Analyses were adjusted for patients’ age, sex and traditional risks of CAD including diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 648, 250, 249), hypertension (ICD-9-CD 401), dyslipidaemia (ICD-9-CM 272), renal failure (ICD-9-CM 586, 585.9), atherosclerosis (ICD-9-CM 440) and CAD-related medications including steroids, antidiabetics, diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, lipid lowing agents, aspirin and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) using regression models. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the cumulative incidences of CAD in patients with and without IMID. A p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 58 862 patients with IMIDs and 1 000 000 control patients aged ≧18 years were identified between 2007 and 2016. The demographic background, baseline traditional risk factors and related medication of CAD are shown in table 1. There were 26 820 patients with RA, 17 530 with SjS, 10 014 with SLE, 1488 with IIM, 1373 with SSc, 1161 with BD, and 476 patients with SV in our study. In terms of gender, the control group of patients was well balanced with an almost equal number of males and females (50.2% females, numbering 501 845), but with females in greater number among patients with RA (76.5%), SjS (90.4%), SLE (87.5%), IIM (67.3%), SSc (71.7%), BD (56.7%) or SV (55.5%). In terms of age group, the largest proportion of RA, SjS, IIM, and SSc patients were between 50 and 64 years. For SLE, the majority were between ages 18 and 34 years, while for BD it was 35–49 years. The three most common forms of IMID in Taiwan were RA, SjS and SLE. Traditional risk factors were higher at baseline in the cohorts of RA, SjS, IIM, SSc and SV, encompassing diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia; exposure to medication including steroids, antidiabetics, diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, lipid-lowing agents, aspirin and NSAIDs was also greater in these patient cohorts (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease and control

| RA N=26 820 (%) |

Sjogren’s syndrome N=17 530 (%) |

SLE N=10 014 (%) |

IIM N=1488 (%) |

Systemic sclerosis N=1373 (%) |

Behcet’s disease N=1161 (%) |

Systemic vasculitis N=476 (%) |

Control N=1 000 000 (%) |

|

| Age (y/o) | ||||||||

| Mean | 53.3 (13.9) | 53.5 (13.7) | 39.4 (15.3) | 50.2 (14.3) | 52.0 (13.9) | 38.8 (12.2) | 46.6 (16.5) | 43.1 (16.3) |

| 18–34 | 2574 (9.6) | 1637 (9.3) | 4421 (44.2) | 210 (14.1) | 163 (11.9) | 459 (39.5) | 130 (27.3) | 351 769 (35.2) |

| 35–49 | 7704 (28.7) | 4842 (27.6) | 3247 (32.4) | 488 (32.8) | 382 (27.8) | 473 (40.7) | 137 (28.8) | 314 808 (31.5) |

| 50–64 | 10 810 (40.3) | 7365 (42.0) | 1583 (15.8) | 564 (37.9) | 582 (42.4) | 195 (16.8) | 138 (29.0) | 222 444 (22.2) |

| 65–79 | 4942 (18.4) | 3206 (18.3) | 585 (5.8) | 193 (13.0) | 218 (15.9) | 34* | 62 (13.0) | 86 308 (8.6) |

| >80 | 790 (3.0) | 480 (2.7) | 178 (1.8) | 33 (2.2) | 28 (2.0) | 9 (1.9) | 24 671 (2.5) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 20 516 (76.5) | 15 847 (90.4) | 8765 (87.5) | 1002 (67.3) | 985 (71.7) | 658 (56.7) | 264 (55.5) | 501 845 (50.2) |

| Male | 6304 (23.5) | 1683 (9.6) | 1249 (12.5) | 486 (32.7) | 388 (28.3) | 503 (43.3) | 212 (44.5) | 498 155 (49.8) |

| Baseline traditional risk factors | 4101 (15.3) | 3074 (17.5) | 958 (9.6) | 255 (17.14) | 238 (17.33) | 87 (7.5) | 60 (12.61) | 79 138 (7.9) |

| DM | 3062 (11.4) | 1736 (9.9) | 645 (6.4) | 171 (11.5) | 158 (11.5) | 53 (4.6) | 69 (14.5) | 65 047 (6.5) |

| HTN | 5639 (21.0) | 3494 (19.9) | 1445 (14.4) | 320 (21.5) | 327 (23.8) | 94 (8.1) | 118 (24.8) | 109 115 (10.9) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 4101 (15.3) | 3074 (17.5) | 958 (9.6) | 255 (17.1) | 238 (17.3) | 87 (7.5) | 60 (12.6) | 79 138 (7.9) |

| Renal failure | 101 (0.4) | 76 (0.4) | 118 (1.2) | 8 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 8* | 17 (3.6) | 1267 (0.1) |

| Atherosclerosis | 171 (0.6) | 109 (0.6) | 53 (0.5) | 9 (0.6) | 34 (2.5) | 16 (3.4) | 2149 (0.2) | |

| Related medications | ||||||||

| Steroids | 21 350 (79.6) | 10 118 (57.7) | 8904 (88.9) | 1445 (97.1) | 992 (72.3) | 977 (84.2) | 424 (89.1) | 177 426 (17.7) |

| Antidiabetics | 2344 (8.7) | 1119 (6.4) | 645 (6.4) | 170 (11.4) | 123 (9.0) | 32 (2.8) | 88 (18.5) | 54 428 (5.4) |

| Diuretics | 4773 (17.8) | 2028 (11.6) | 3172 (31.7) | 531 (35.7) | 422 (30.7) | 76 (6.6) | 192 (40.3) | 45 533 (4.6) |

| Beta-blockers | 4314 (16.1) | 3648 (20.8) | 1982 (19.8) | 328 (22.0) | 262 (19.1) | 162 (14.0) | 148 (31.1) | 83 688 (8.4) |

| CCBs | 4712 (17.6) | 3114 (17.8) | 1921 (19.2) | 356 (23.9) | 519 (37.8) | 90 (7.8) | 167 (35.1) | 89 526 (9.0) |

| Lipid lowing agents | 2365 (8.8) | 1816 (10.4) | 829 (8.3) | 156 (10.5) | 139 (10.1) | 37 (3.2) | 53 (11.1) | 55 615 (5.6) |

| Aspirin | 3318 (12.4) | 2246 (12.8) | 2233 (22.3) | 260 (17.5) | 410 (29.9) | 165 (14.2) | 174 (36.6) | 55 270 (5.5) |

| NSAIDs | 26 372 (98.3) | 15 126 (86.3) | 8625 (86.1) | 1306 (87.8) | 1146 (83.5) | 1023 (88.1) | 398 (83.6) | 607 623 (60.8) |

*Analysis number is combined due to risk of patient identification.

CCB, calcium channel blocker; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; IIM, idiopathic inflammatory myositis; NSAID, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Risks of hospital admission for CAD and premature CAD

The cohort was followed from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2016, and the total mean follow-up time was 5.3 years (table 2). There were 1141 (4.3%), 534 (3.0%), 281 (2.8%), 59 (4.0%), 84 (6.1%), 18 (1.6%) and 22 (4.6%) CAD-related hospitalisations among patients with RA, SjS, SLE, IIM, SSc, BD and SV, respectively. During this period, there were 2139 (3.6%) and 20 247 (2.0%) CAD-related hospitalisations among patients with IMID and the general population (table 2). We then compared by age group the incidence of CAD in our IMID cohort with the patients without IMID, as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Risk evaluation for admission CAD in patients with specific immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

| Patient no | Admission CAD events | Follow-up years (mean) | Admission CAD incidence rate per 100 PY | Crude HR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Main analysis | ||||||||

| All IMID | 58 862 | 2139 | 5.3 | 0.69 | 1.93 (1.84 to 2.02) | <0.0001 | 1.30 (1.24 to 1.37) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 26 820 | 1141 | 5.6 | 0.76 | 2.12 (2.00 to 2.25) | <0.0001 | 1.21 (1.13 to 1.28) | <0.0001 |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 17 530 | 534 | 4.6 | 0.66 | 1.86 (1.71 to 2.03) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.15 to 1.37) | <0.0001 |

| SLE | 10 014 | 281 | 5.5 | 0.51 | 1.42 (1.27 to 1.60) | <0.0001 | 1.78 (1.58 to 2.01) | <0.0001 |

| IIM | 1488 | 59 | 4.7 | 0.84 | 2.37 (1.83 to 3.05) | <0.0001 | 1.63 (1.26 to 2.10) | 0.0002 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 1373 | 84 | 5.0 | 1.22 | 3.44 (2.78 to 4.26) | <0.0001 | 1.96 (1.58 to 2.43) | <0.0001 |

| Behcet’s disease | 1161 | 18 | 6.7 | 0.23 | 0.65 (0.41 to 1.03) | 0.065 | 0.90 (0.56 to 1.42) | 0.64 |

| Systemic vasculitis | 476 | 22 | 5.2 | 0.89 | 2.53 (1.67 to 3.83) | <0.0001 | 1.20 (0.79 to 1.83) | 0.38 |

| General population | 1 000 000 | 20 247 | 5.7 | 0.36 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Subgroup analysis | ||||||||

| Men aged <45 years, women <50 years | ||||||||

| All IMID | 25 674 | 346 | 5.9 | 0.23 | 2.6 (2.32 to 2.9) | <0.0001 | 1.71 (1.51 to 1.94) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 9534 | 102 | 6.2 | 0.17 | 1.91 (1.57 to 2.33) | <0.0001 | 1.16 (0.94 to 1.42) | 0.158 |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 6306 | 58 | 5.1 | 0.18 | 2.14 (1.65 to 2.77) | <0.0001 | 1.43 (1.09 to 1.86) | 0.009 |

| SLE | 7559 | 143 | 5.9 | 0.32 | 3.58 (3.03 to 4.23) | <0.0001 | 2.85 (2.36 to 3.43) | <0.0001 |

| IIM | 660 | 13 | 5.6 | 0.35 | 3.99 (2.31 to 6.88) | <0.0001 | 1.73 (0.99 to 3.03) | 0.054 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 493 | 18 | 6.1 | 0.60 | 6.78 (4.27 to 10.78) | <0.0001 | 3.18 (1.99 to 5.09) | 0.0001 |

| Behcet’s disease | 877 | 6 | 6.9 | 0.10 | 1.1 (0.49 to 2.44) | 0.820 | 0.74 (0.33 to 1.66) | 0.472 |

| Systemic vasculitis | 245 | 6 | 6.0 | 0.41 | 4.56 (2.05 to 10.15) | <0.0001 | 2.27 (1.01 to 5.07) | 0.046 |

| General population | 615 280 | 3294 | 6.0 | 0.09 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Men aged ≥45 years, women ≥50 years | ||||||||

| All IMID | 33 188 | 1793 | 4.8 | 1.11 | 1.3 (1.23 to 1.36) | <0.0001 | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.24) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 17 286 | 1039 | 5.3 | 1.14 | 1.32 (1.24 to 1.4) | <0.0001 | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) | <0.0001 |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 11 224 | 476 | 4.4 | 0.97 | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.25) | 0.05 | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28) | 0.002 |

| SLE | 2455 | 138 | 4.3 | 1.31 | 1.53 (1.29 to 1.8) | <0.0001 | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.49) | 0.009 |

| IIM | 828 | 46 | 4.1 | 1.37 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.13) | 0.002 | 1.41 (1.06 to 1.89) | 0.020 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 880 | 66 | 4.4 | 1.69 | 1.98 (1.55 to 2.52) | <0.0001 | 1.62 (1.27 to 2.06) | <0.0001 |

| Behcet’s disease | 284 | 12 | 6.1 | 0.69 | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.4) | 0.422 | 0.92 (0.52 to 1.61) | 0.761 |

| Systemic vasculitis | 231 | 16 | 4.3 | 1.62 | 1.9 (1.16 to 3.1) | 0.011 | 0.98 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.942 |

| General population | 384 720 | 16 953 | 5.1 | 0.86 | Reference | Reference |

*Adjusted by age, sex, DM, HTN, dyslipidaemia, renal failure, atherosclerosis, steroids, antidiabetics, diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blocker, lipid lowing agents, aspirin, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs.

CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; IIM, idiopathic inflammatory myositis; IMID, immune-mediated inflammatory disease; PY, person-years; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

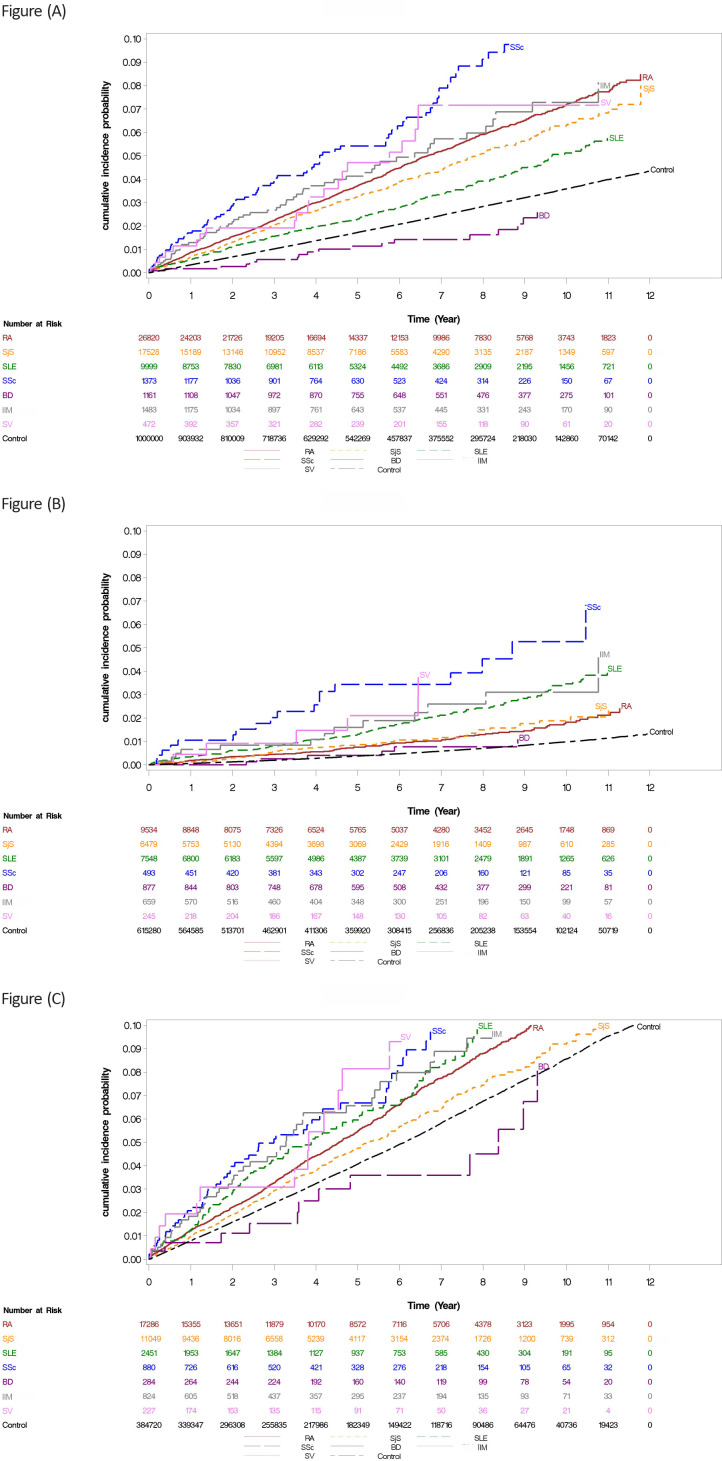

Table 3 shows the risk of hospitalisation for CAD associated with the traditional risk factors; as our study confirms, increased age, male gender, DM, HTN and renal failure are all associated with an increased risk of CAD. This study further identifies the higher risk of developing CAD for patients with IMIDs including RA, SjS, SLE, IIM and SSc, relative to the comparisons. After adjusting for traditional risk factors and related medications, the adjusted HRs for CAD were still significantly higher than their comparisons in patients with RA: 1.21 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.28), SjS: 1.25 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.37), SLE: 1.78 (95% CI 1.58 to 2.01), IIM: 1.63 (95% CI 1.26 to 2.10) and SSc: 1.96 (95% CI 1.58 to 2.43) (table 2 and figure 1A).

Table 3.

Traditional risk factors and related medication of CAD

| All | ||

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| IMID | 1.30 (1.24 to 1.37) | <0.0001 |

| Tradition risk factors of CAD | ||

| Age | 1.06 (1.06 to 1.06) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 1.87 (1.82 to 1.92) | <0.0001 |

| DM | 1.26 (1.19 to 1.34) | <0.0001 |

| HTN | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.02) | 0.37 |

| Renal failure | 1.73 (1.49 to 2.01) | <0.0001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.19) | 0.50 |

| Related medication | ||

| Steroids | 1.17 (1.14 to 1.21) | <0.0001 |

| Antidiabetics | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 1.28 (1.24 to 1.33) | <0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers | 1.42 (1.37 to 1.47) | <0.0001 |

| CCB | 1.35 (1.30 to 1.40) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid Lowing agents | 1.26 (1.20 to 1.32) | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin | 1.47 (1.42 to 1.52) | <0.0001 |

| NSAIDs | 1.15 (1.12 to 1.19) | <0.0001 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; IMID, immune-mediated inflammatory disease; NSAID, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidences of coronary artery disease in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method (A) and by men age <45 and women age <50 (B) or men age ≥45 and women age ≥50 y/o (C). BD, Behcet’s disease; IIM, idiopathic inflammatory myositis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SjS, Sjogren’s syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SSc, systemic sclerosis; SV, systemic vasculitis.

We further divided the patients into two groups (men age <45 and women age <50 or men age ≥45 and women age ≥50 y/o) to expose the premature CAD risk in our IMID cohorts. Among 25 674 patients with IMID, 346 (1.3%) developed premature CAD (defined for men as appearing before age 45 and for women before age 50). Relative to the comparisons, the adjusted HRs for premature CAD were 1.43 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.86) for SjS, 2.85 (95% CI 2.36 to 3.43) for SLE, 3.18 (95% CI 1.99 to 5.09) for SSc and 2.27 (95% CI 1.01 to 5.07) for SV. A marked increase in premature CAD is thus identified among patients with SjS, SLE, SSc and SV compared with the non-IMID comparisons, with all p<0.05 (table 2 and figure 1B, C).

Discussion

In our study, the risk of hospitalisation for CAD or premature CAD in patients with IMID was investigated in a population-based cohort followed for 9 years. The prevalence of traditional CAD risk factors including diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia was higher in patients with RA, SjS, IIM, SSc and SV at the baseline relative to general population, which is attributable to the proportion of older cohort members likely to use more medication for CAD. These were important confounding factors which may lead to overestimation regarding risk of CAD among patients with IMID. After adjustment for age, sex, traditional risks of CAD and CAD-related medications, a marked increase was observed in risk of developing CAD in patients with RA, SjS, SLE, IIM and SSc when compared with their comparisons. CAD has been identified as the primary cause of adult deaths within the general population,1 25 26 also constituting a major cause of death in patients with IMID.5 27–33

Although atherosclerotic CV events have been declining in older adults, the proportion of AMI hospitalisations attributable to young patients increased from 1995 to 2014.3 After adjustment for age, sex, traditional risks of CAD and CAD-related medications, a marked increase was observed in the risk of developing premature CAD in patients with SjS, SLE, SSc and SV when compared with their comparisons. Our study identifies an increase of around 40% in the risk of incident premature CAD for SjS, a threefold increase for SLE, around a threefold rise for SSc and a twofold rise for SV when set beside their respective comparisons. The results indicate an age-dependent pattern of CAD risk among patients with certain IMIDs.

The majority of IMIDs are relatively rare and studies evaluating risk factors for premature CAD are limited in number and scope. To our knowledge, ours is the first study dedicated to examining the risk of hospitalisation for premature CAD in individual IMIDs with a nationwide population-based cohort. With recent studies finding that concomitant inflammatory and autoimmune disorders in younger adults are associated with poor prognoses,20 21 our work clarifies that greater attention should be paid to the younger population. Our study finds that SjS, SLE, SSc and SV should be regarded as independent risk factors in respect of developing premature CAD. Despite currently recommended prevention measures, premature CAD remains an aggressive disease characterised by high rates of recurrent events and mortality.

Our results correspond well with those of previous studies establishing a link between individual IMIDs, to include RA,5 32 SLE,16 34–36 SSc,17 IIM29 37 and chronic inflammation along with increased risk of CAD. An age-dependent pattern of CAD risk has previously been reported, with higher levels of risk found in younger patients with RA and SLE.19 38 39 Premature CAD carries a poor long-term prognosis so it is paramount that we understand and explain unique risk factors to prevent CAD events in younger populations. Systemic inflammation appears responsible for the elevated risk, whether directly due to deleterious effects of endothelial dysfunction, or indirectly through accentuation of multiple risk pathways such as lipid abnormalities.40–42

After adjusting for traditional risk factors and related medications, the adjusted HRs for CAD was 1.21 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.28), and aHD for premature CAD was 1.13 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.36) in patients with RA, respectively. The results were different from previous studies suggesting that patients with RA had increased risk of premature atherosclerosis.38 39 In addition to racial and ethnic disparities in patients with RA,43 different study designs including definitions of study populations, outcomes and the baseline covariates among studies, could be the likely explanations. Moreover, a previous study indicated the hospitalisations rate for CAD has fallen since 2004,44 due to increased awareness of CAD and preventive treatment. Because our study included more recent data (2004–2016) compared with previous studies (1997–2006), the difference of study period could be another possible explanation for the inconsistency of results.

The results of our study showed that BD does not increase the risk of CAD in all age groups. This is consistent with the findings from previous studies in Taiwan45 and in the UK.46 However, one study from Korea revealed the risk of myocardial infarction was 60% higher for patients with BD than for general population.47 The likely explanation for the discrepant results is that Korea is located along the Silk Road, the vast network of ancient trade routes connecting China with the Mediterranean Basin including Korea48 where BD is both more common and more severe.

A significant strength of our study is the nationwide population cohort, facilitated by our access to a substantial database of sufficient power for the study of rare disease such as premature CAD; in addition, we had access to data on CV risk factors, alongside that for related use of medication. Third, claims data linked to patient assessments for the CIC offers a high degree of diagnosis validity, producing a reliable data set and valuable opportunity to estimate the incidence of premature CAD among patients with specific forms of IMID. Fourth, we ruled out all those who had a CAD history traceable within 3 years prior to the follow-up period, ensuring that we excluded recurrent patients from our study, thus avoiding any overestimation of risk regarding CAD.

Like all studies using a claims database, our study is subject to an inherited limitation in that the NHIRD were not able to show control of different levels of severity/activity for patients’ IMID, diabetes, hypertension, etc. By including in the IMID cohort only those who had applied for a CIC, any IMID patients who had not applied will not be part of our study; however, since approval for a CIC means exemption for copayment, we can assume that the number of patients with IMID but no CIC is likely to be low. The competing risks of cancers and interstitial lung disease are also a concern, but the effect on this study is relatively minor since the number of affected patients will be very small and is less likely to have influenced the results significantly. In using the NHIRD, we did not have access to information regarding patient body weight, exercise activity, smoking and diet, all of which may also have a bearing on the appearance and outcomes of CAD. Although we adjusted for the use of steroids and the results did not change substantially after adjustments, potential confounding effects due to the use of steroids should be considered.

Conclusions

Our study found an increase of 40% in the risk of incident premature CAD for SjS, a threefold increase for SLE, around a threefold rise for SSc and a twofold rise in SV when set beside their respective comparisons. These findings support essential efforts to improve awareness of IMID impacting young adults.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Health Data Science) Centre, National Cheng Kung University Hospital for providing administrative and technical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors approved the final version before submission. M-YW and Y-CH contributed to literature search, study concept and design. T-CL, EC-CL and M-YW were involved in data analysis and interpretation of the results. EC-CL and M-YW had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from National Cheng Kung University Hospital (NCKUH-10803039).

Disclaimer: The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (A-EX-107–047) of National Cheng-Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan. All data in the study were anonymous.

References

- 1.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 2001;104:2746–53. 10.1161/hc4601.099487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation 2001;104:2855–64. 10.1161/hc4701.099488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora S, Stouffer GA, Kucharska-Newton AM, et al. Twenty year trends and sex differences in young adults hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2019;139:1047–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vikulova DN, Grubisic M, Zhao Y, et al. Premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: trends in incidence, risk factors, and sex-related differences, 2000 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012178. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.del Rincón ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. Do cardiovascular risk factors confer the same risk for cardiovascular outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients as in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients? Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:64–9. 10.1136/ard.2006.059980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, et al. Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2000;101:2883–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.25.2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niessner A, Sato K, Chaikof EL, et al. Pathogen-sensing plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulate cytotoxic T-cell function in the atherosclerotic plaque through interferon-alpha. Circulation 2006;114:2482–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Magadmi M, Bodill H, Ahmad Y, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: an independent risk factor for endothelial dysfunction in women. Circulation 2004;110:399–404. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136807.78534.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J. Rheumatoid arthritis: a disease associated with accelerated atherogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;35:8–17. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1685–95. 10.1056/NEJMra043430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Mechanisms of disease: atherosclerosis in autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2006;2:99–106. 10.1038/ncprheum0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2003;107:1303–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000054612.26458.B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasad M, Hermann J, Gabriel SE, et al. Cardiorheumatology: cardiac involvement in systemic rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:168–76. 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoenfeld Y, Gerli R, Doria A, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Circulation 2005;112:3337–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hak AE, Karlson EW, Feskanich D, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the risk of cardiovascular disease: results from the nurses' health study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1396–402. 10.1002/art.24537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngian G-S, Sahhar J, Proudman SM, et al. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular risk factors in a national cross-sectional cohort study of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1980–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X-F, Huang J-Y, Chiou J-Y, et al. Increased risk of coronary heart disease among patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 2018;8:2209. 10.1038/s41598-018-19580-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahtta D, Gupta A, Ramsey DJ, et al. Autoimmune rheumatic diseases and premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an analysis from the vital registry. Am J Med 2020;133:1424–32. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collet J-P, Zeitouni M, Procopi N, et al. Long-Term Evolution of Premature Coronary Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1868–78. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1376–414. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare . National health insurance annual report 2014-2015 2014.

- 23.Patients with catastrophic illnesses or rare diseases. Available: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/english/Content_List.aspx?n=F5B8E49CB4548C60&topn=1D1ECC54F86E9050

- 24.Cheng C-L, Lee C-H, Chen P-S, et al. Validation of acute myocardial infarction cases in the National health insurance research database in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2014;24:500–7. 10.2188/jea.JE20140076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:948–54. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006;367:1747–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Airio A, Kautiainen H, Hakala M. Prognosis and mortality of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:234–9. 10.1007/s10067-005-1164-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobloug GC, Svensson J, Lundberg IE, et al. Mortality in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: results from a Swedish nationwide population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:40–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Moss K, et al. Outcome in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis: morbidity and mortality. Rheumatology 2002;41:22–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dankó K, Ponyi A, Constantin T, et al. Long-Term survival of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies according to clinical features: a longitudinal study of 162 cases. Medicine 2004;83:35–42. 10.1097/01.md.0000109755.65914.5e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hochberg MC, Feldman D, Stevens MB. Adult onset polymyositis/dermatomyositis: an analysis of clinical and laboratory features and survival in 76 patients with a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1986;15:168–78. 10.1016/0049-0172(86)90014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmqvist ME, Wedrén S, Jacobsson LTH, et al. Rapid increase in myocardial infarction risk following diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis amongst patients diagnosed between 1995 and 2006. J Intern Med 2010;268:578–85. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skaggs BJ, Hahn BH, McMahon M. Accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with SLE--mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:214–23. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asanuma Y, Oeser A, Shintani AK, et al. Premature coronary-artery atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2407–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa035611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wierzbicki AS. Lipids, cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2000;9:194–201. 10.1191/096120300678828235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruce IN, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB. Premature atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:257–78. 10.1016/S0889-857X(05)70138-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng M-Y, Lai EC-C, Kao Yang Y-H. Increased risk of coronary heart disease among patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Rheumatology 2019;58:1935–41. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:929–34. 10.1136/ard.2010.143396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solomon DH, Goodson NJ, Katz JN, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1608–12. 10.1136/ard.2005.050377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, et al. Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists' view. Eur Heart J 2013;34:719–28. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sattar N, McInnes IB. Vascular comorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis: potential mechanisms and solutions. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2005;17:286–92. 10.1097/01.bor.0000158150.57154.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, et al. Explaining how "high-grade" systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2003;108:2957–63. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenberg JD, Spruill TM, Shan Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 2013;126:1089–98. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nedkoff L, Goldacre R, Greenland M, et al. Comparative trends in coronary heart disease subgroup hospitalisation rates in England and Australia. Heart 2019;105:1343–50. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin C-Y, Chen H-A, Wu C-H, et al. Is Behçet's syndrome associated with an increased risk of ischemic heart disease? A real-world evidence in Taiwan. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:161. 10.1186/s13075-021-02543-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas T, Chandan JS, Subramanian A, et al. Epidemiology, morbidity and mortality in Behçet's disease: a cohort study using the health improvement network (thin). Rheumatology 2020;59:2785–95. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahn H-S, Lee D, Lee SY, et al. Increased cardiovascular risk and all-cause death in patients with Behçet disease: a Korean nationwide population-based dynamic cohort study. J Rheumatol 2020;47:903–8. 10.3899/jrheum.190408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho SB, Cho S, Bang D. New insights in the clinical understanding of Behçet's disease. Yonsei Med J 2012;53:35–42. 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Not applicable.