Abstract

For an engineered thick tissue construct to be alive and sustainable, it should be perfusable with respect to nutrients and oxygen. Embedded printing and then removing sacrificial inks in a cross-linkable yield-stress hydrogel matrix bath can serve as a valuable tool for fabricating perfusable tissue constructs. The objective of this study is to investigate the printability of sacrificial inks and the creation of perfusable channels in a cross-linkable yield-stress hydrogel matrix during embedded printing. Pluronic F-127, methylcellulose, and polyvinyl alcohol are selected as three representative sacrificial inks for their different physical and rheological properties. Their printability and removability performances have been evaluated during embedded printing in a gelatin microgel-based gelatin composite matrix bath, which is a cross-linkable yield-stress bath. The ink printability during embedded printing is different from that during printing in air due to the constraining effect of the matrix bath. Sacrificial inks with a shear-thinning property are capable of printing channels with a broad range of filaments by simply tuning the extrusion pressure. Bi-directional diffusion may happen between the sacrificial ink and matrix bath, which affects the sacrificial ink removal process and final channel diameter. As such, sacrificial inks with a low diffusion coefficient for gelatin precursor are desirable to minimize the diffusion from the gelatin precursor solution to minimize the post-printing channel diameter variation. For feasibility demonstration, a multi-channel perfusable alveolar mimic has been successfully designed, printed, and evaluated. The study results in the knowledge of the channel diameter controllability and sacrificial ink removability during embedded printing.

I. INTRODUCTION

With recent advances in materials and fabrication technologies, the development of engineered tissue constructs has been of great interest for various tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. In particular, three-dimensional (3D) engineered tissues may be used as more realistic in vitro models for biomedical uses such as drug screening, tumor metastasis evaluation, and disease therapy development by providing a more physiologically relevant microenvironment than a two-dimensional (2D) culture.1–4 Due to the diffusion limit, a distance of 200 μm or more is usually difficult for oxygen and nutrients to reach,5 and vascularization is indispensable for the maintenance of living tissues thicker than the diffusion limit. Therefore, the availability of perfusable channels is of great significance for thick tissues, which can enable much-needed mass-transport processes.4,6–8

The creation of perfusable channels in thick tissues can be accomplished in two main approaches in addition to layer-by-layer direct printing: pattern-based molding and embedded printing of a sacrificial pattern in a matrix. The pattern-based molding approach is to cast a matrix precursor around a sacrificial channel pattern in the mold cavity, followed by removing the pattern after cross-linking the matrix to expose channels.9–11 Some complicated channel patterns can be 3D printed, such as carbohydrate glass12 and Pluronic F-12713 lattice patterns used for perfusable channel creation. However, since the pattern structure needs to be self-supported, some complex 3D patterns may not be manufacturable. Besides, some features of sacrificial patterns may be flushed away during matrix casting.

Alternatively, the embedded printing approach, directly writing a sacrificial pattern into a matrix precursor material, has recently drawn attention for perfusable channel creation.14,15 This approach requires the matrix bath to have specific rheological properties to allow the translation of printing nozzle in the matrix bath while maintaining deposited structures. In general, support matrix bath materials are required to be yield-stress fluids and cross-linkable after printing is completed. Yield-stress fluids behave as solids at rest but transform to a liquid-like state if the applied shear stress exceeds a threshold (defined as the yield stress).15 This property allows the translation of the nozzle in the matrix bath and helps hold the shape of deposited inks in situ. Therefore, embedded printing is capable of printing a wide range of soft hydrogel materials that cannot form free-standing structures in air. Moreover, the utilization of sacrificial materials in embedded printing makes it possible to fabricate acellular and cellular structures with considerable complexity.15–18 For the advantages of freeform production and high efficiency, the embedded printing of sacrificial inks has become one of the most promising methods to fabricate perfusable channel networks in a hydrogel matrix. It should be noted that the concept of sacrificial material-based printing can be implemented for a broad range of non-biological applications such as the printing of negative templates for subsequent pattern deposition,19 and the concept of embedded printing can be utilized to deposit non-biomaterial inks in an engineering material bath such as inkjet printing a silver nanoparticle ink into a liquid poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) precursor bath.20

The physical properties of sacrificial ink materials used in embedded printing play a crucial role in affecting the printing performance and quality of resulting channels, including the printing and post-printing removal processes. In addition to those for general bioprinting in air such as the biocompatibility, printability, and mechanical properties,21–24 low stiffness inks become printable by the embedded approach with the help of the surrounding matrix, thus extending the printable viscosity range and achievable structure complexity. However, additional constraints are required for embedded printing, such as the post-printing ink diffusivity and removability. Minimal diffusion across the sacrificial ink and matrix interface is favorable to avoid the matrix contamination and better control the channel diameter. As a sacrificial ink, it is required to be easily liquefied for removal after the cross-linking of the matrix. Optimal sacrificial inks should have a controllable phase-transition property from gel to liquid for evacuation after printing. Stimuli for such phase transition can be temperature, basic or acidic environment, selective dissolution, and enzymatic cleavage.14 In order to avoid any damages to the embedded cells in the hydrogel matrix, a mild phase-transition condition is more favorable for being a good sacrificial ink. While the potential of embedded printing has been widely recognized for perfusable channel creation, systematic investigations are still needed regarding the selection of applicable sacrificial inks. In particular, the difference of ink printability between embedded printing and in-air printing and its dependence on the rheology properties have not been well explored. Furthermore, the diffusion phenomenon between the hydrophilic ink and cross-linkable matrix bath for embedded printing and its effect on the channel diameter variation are still elusive.

The objective of this study is to evaluate three representative sacrificial ink materials [Pluronic F-127, methylcellulose (MC), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)] for perfusable channel creation during embedded printing in a yield-stress matrix bath, in particular, in terms of the ink printability, post-printing ink removability, and post-printing chemical diffusion. Typical sacrificial ink materials used in bioprinting are thermo-reversible to facilitate the printing and removal processes, including carbohydrate glass,12 agarose,25 gelatin,26 and Pluronic F-127.13,27,28 In addition, water-soluble materials such as MC29 and PVA11,30 are also suitable sacrificial ink materials due to the ease of their post-printing evacuation. Of common thermo-reversible materials, carbohydrate glass and agarose need an elevated temperature (∼80–100 °C) for phase change, so they are good for the sacrificial structure printing-then-casting approach but not suitable for embedded printing in a cell-laden support matrix. While gelatin requires a lower phase transition temperature around 25–35 °C,31 it is not a suitable sacrificial ink for this study since the matrix for embedded printing contains transglutaminase (TG), which may enzymatically cross-link gelatin solutions. As such, Pluronic F-127 is selected as a thermo-reversible ink material for this study, which liquifies at 4 °C and solidifies at room temperature. Of common water-soluble materials, both MC and PVA are selected since they have different shear-thinning properties, which may illustrate the significance of the shear-thinning property on perfusable channel creation. It should be noted that the identification of the best sacrificial ink materials is not the focus of this study since different perfusable tissue applications may involve different matrix materials and have their own physical and/or chemical constraints on sacrificial ink materials. Instead, this study aims to evaluate several critical features associated with their use as sacrificial inks for embedded printing in a gelatin microgel-based, yield-stress matrix bath.15 For better evaluation of sacrificial inks for perfusable channel creation in engineered living tissues, the printability of sacrificial patterns and channel formation are specifically investigated in this study.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Material preparation

1. Preparation of sacrificial inks

Pluronic F-127 inks were prepared by dissolving and stirring the Pluronic F-127 powders (molecular weight ∼12 600 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in deionized water, followed by fully dissolving at 4 °C overnight to have the 20%, 23%, 25%, and 30% (w/v) inks. Of them, 20%, 23%, 25%, and 30% were used for rheological characterization; since the 20% ink is too fluidic and diffusive for the gelatin solution, only 23%, 25%, and 30% were used for printability evaluation, and only 23% and 30% (lowest and highest concentrations) were studied for removability and diffusion tests. MC inks were prepared by dissolving the MC powders (molecular weight ∼88 000 g/mol, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) in de-ionized water at 55 °C for 1 h, followed by cooling at 4 °C overnight for full hydration of the MC polymer chains until no deposits were observed. Concentrations of 1.0%, 2.5%, 4.0% (w/v) were obtained. Of them, the 1.0%, 2.5%, and 4.0% inks were used for rheological characterization and printability evaluation; since the 1.0% ink is too diffusive for the gelatin solution, only the 2.5% and 4.0% inks were evaluated for removability and diffusion tests. PVA inks were prepared by dissolving the PVA powders (molecular weight ∼22 000 g/mol, degree of hydrolysis 88%, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) in de-ionized water at 70 °C for swelling and then heated up to 95 °C for at least 1 h to have the 36%, 38%, and 40% (w/v) inks. Of them, 36%, 38%, and 40% were used for rheological characterization and printability evaluation, and 36% and 40% (lowest and highest concentrations) for removability and diffusion tests. All the prepared ink materials were stored at room temperature until use.

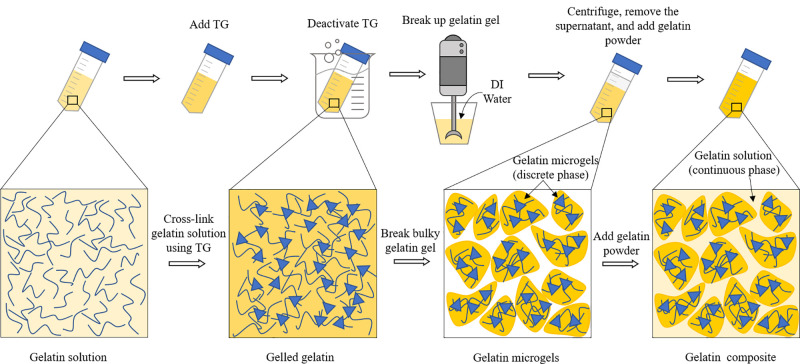

2. Preparation of gelatin microgels and gelatin composite

The supporting matrix used in this embedded printing study is a gelatin microgel-based composite, where a gelatin precursor acts as the continuous matrix while jammed microgels act as the rheology modifier, and its preparation process is illustrated in Fig. 1. First, 5 g gelatin powders (225 bloom type A, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) was dissolved in 47.5 ml Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (dPBS, Corning cellgro Manassas, VA, USA) in a 50 ml centrifuge tube for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the gelatin solution was mixed with a 2.5 ml 20% w/v transglutaminase (TG, Modernist Pantry, York, ME, USA) solution (prepared by dissolving the TG powders into dPBS), to achieve a final concentration of 10% w/v gelatin and 1.0% w/v TG. After incubation in a silver bead bath for 24 h at 37 °C, the cross-linked gelatin gel bulk was heated in boiling water for 30 min to deactivate the residual TG. After that, the gelatin gel was removed from the tube into a blender container for thoroughly breaking up into microgels using a 3-speed hand blender (KitchenAid, Benton Harbor, MI, USA). To facilitate the breakup process, 50–100 ml DI water was added to the container. After the gel breakup process, the gelatin microgels were collected and centrifuged at 4200 rpm for 5 min to remove the water supernatant. Then, 3% w/v gelatin powders were added into the microgel tube for 30 min at 37 °C for them to be dissolved. The obtained gelatin composite contained discrete gelatin microgels and a continuous gelatin precursor solution and was stored at 4 °C until use as the matrix bath. The resulting gelatin composite is a colloid with homogeneously distributed gelatin microgels as illustrated in a previous study.15

FIG. 1.

Schematics of the gelatin matrix preparation procedures.

B. Rheological characterization

Rheological properties of the Pluronic F-127, MC, and PVA inks were measured using a rheometer (MCR-702 TwinDrive, Anton-Paar, Graz, Austria) as described in a previous study.32 Specifically, the viscosity and shear stress were measured by steady rate sweeps with a shear rate range from 0.01 to 100.00 s−1 at a strain of 1.0%.

C. Printing study

The printing study was performed using a pneumatic 3D bioprinter (CELLINK INKREDIBLE, Boston, MA, USA) with a general-purpose gauge 22 dispensing tip (inner diameter of 0.41 mm, Nordson EFD, East Providence, RI, USA) at room temperature. For comparison, the inks and air pressure for both embedded printing and printing in air are listed in Table I. The matrix bath for embedded printing was prepared by adding a 20% w/v TG solution into the aforementioned gelatin composite with a volume ratio of 1:19 at 29.5 ± 0.5 °C right before printing. The resulting matrix bath is a yield-stress bath, enabling the embedded printing of 3D patterns.15 For printing in air, glass slides were used as the substrate by being covered with a frost Scotch tape. The path speed was set as 2 mm/s, and customized G-code scripts were programmed to guide the printing paths.

TABLE I.

Printing inks and air pressures for both printing in bath and in air.

| Material | Pluronic F-127 | MC | PVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23% | 25% | 30% | 1.0% | 2.5% | 4.0% | 36% | 38% | 40% | |

| Air pressure (kPa) | 70 | 100 | 130 | 4 | 25 | 70 | 60 | 125 | 165 |

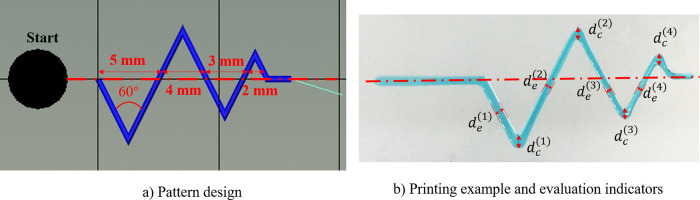

For printability evaluation, a saw-tooth-shaped 2D pattern is proposed as an assessment structure, which contains four connecting equilateral triangles (60°) with a decreasing side length (5, 4, 3, and 2 mm) as shown in Fig. 2(a). The saw-tooth pattern is designed to evaluate the printing quality of features with vertices, which are usually difficult to be printed. Images of the printed patterns were taken right after the printing and then analyzed for the width of the deposited filaments at multiple locations using ImageJ (NIH, USA). For the simplification of benchmark purpose, a printability (P) value is proposed as follows for patterns with three or more legible vertices:

| (1) |

where m is the number of legible vertices, is the width of the mth vertex section, and is the width of the mth straight side section [Fig. 2(b)]. The printability (P) value is introduced herein to account for the printing quality of vertices or sharp concerns, which are significant for perfusable systems in order for them to efficiently and effectively reach the whole construct. For an ink with poor printability, the deposited ink filaments may flow freely and spread out, leading to the ink fusion at the turning regions. As a result, the width of at vertices is usually larger than that of a straight side, indicating worsening printing accuracy. A smaller P value means better printability. While 1 is chosen as the P value threshold to evaluate the printing quality in this perfusion channel printing study, this threshold value can be different based on various printing application needs.

FIG. 2.

Schematics of the assessment pattern and measurement example.

The aforementioned assessment pattern is printed horizontally. It should be noted that there is a difference between the deposition of horizontal and vertical features during embedded printing in a yield-stress bath. Depending on whether the deposited ink interfaces the printing nozzle-induced liquefied zone, printing in horizontal and vertical directions can be very much different in terms of the ink up-flow phenomenon. During horizontal printing, the nozzle dislodges the gelatin composite bath along the printing path, and the yield-stress bath region in the wake of the immersed nozzle is unjammed and liquified due to the shearing force from the moving nozzle. As a result, the region above a horizontally deposited ink filament is liquified, and the deposited ink is less compressive from the immediately above direction, which may lead to an up-flow of the ink. During vertical printing, there is no dispensing nozzle-induced liquefied yield-stress bath region since the ink is dispensed along the nozzle axial direction, which is also the nozzle movement direction. As such, the up-flow phenomenon may be minimized during vertical printing.

D. Post-printing removal of sacrificial materials

The printed samples were kept for 30 min at room temperature to get fully cross-linked before sacrificial material removal. For the removal process, thermal liquefaction was used for Pluronic F-127, and aqueous dissolution was utilized for MC and PVA. Since Pluronic F-127 is an excellent thermo-sensitive material, its samples were placed at 4 °C for 30 min to liquefy the sacrificial ink. Since MC and PVA solutions are water-soluble, the samples were immersed in water for 30 min to remove MC or PVA. After the evacuation of the sacrificial inks, an off-the-shelf red food dye was infilled into the formed channels for better visualization of perfusion flows while the channel diameter was measured based on each cross section after cutting the gelled construct perpendicular to each channel. For each channel, at least three cross sections were examined at different straight side sections along the channel direction.

E. Channel diameter measurement

To evaluate the diffusion process, the change of filament widths of the printed sacrificial inks was monitored by using a microscope (EVOS, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the gelatin bath up to 1 h at an interval of 10 min right after printing, and the final channel diameters after removal were also measured.

F. Alveolar mimic design and cell culture

A multi-channel alveolar mimic was designed and printed to demonstrate the feasibility of the embedded printing approach for perfusable channel creation. NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts (ATCC, Rockville, MD) was used as a model cell to see how a perfusable channel may supply sufficient nutrient and oxygen to the cells in the surrounding matrix. Specifically, 3T3 cells were harvested32,33 and mixed into the sterilized gelatin composite matrix as described previously32,33 to have a final cell concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL. The resulting cellular gelatin composite matrix was further gently mixed with the TG solution to have a final TG concentration of 1% w/v and cast into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chamber for the embedded printing of perfusable channels using the 23% Pluronic F-127 ink. After printing, the construct was cross-linked at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 45 min, followed by the removal of the sacrificial ink at 4 °C for 15 min. After the channels were created, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) was dynamically perfused through the channels using a peristaltic pump (Ismatec, Wertheim, Germany) at a flow rate of 16 μL/min. For the control group, a bulk cellular gelatin composite structure without any channels was cultured under static condition by adding medium on the top surface only, which was changed every two days. After culturing for 4 days, fluorescein diacetate (FDA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used to stain the live and dead cells, respectively.

III. RESULTS

A. Rheological characterization

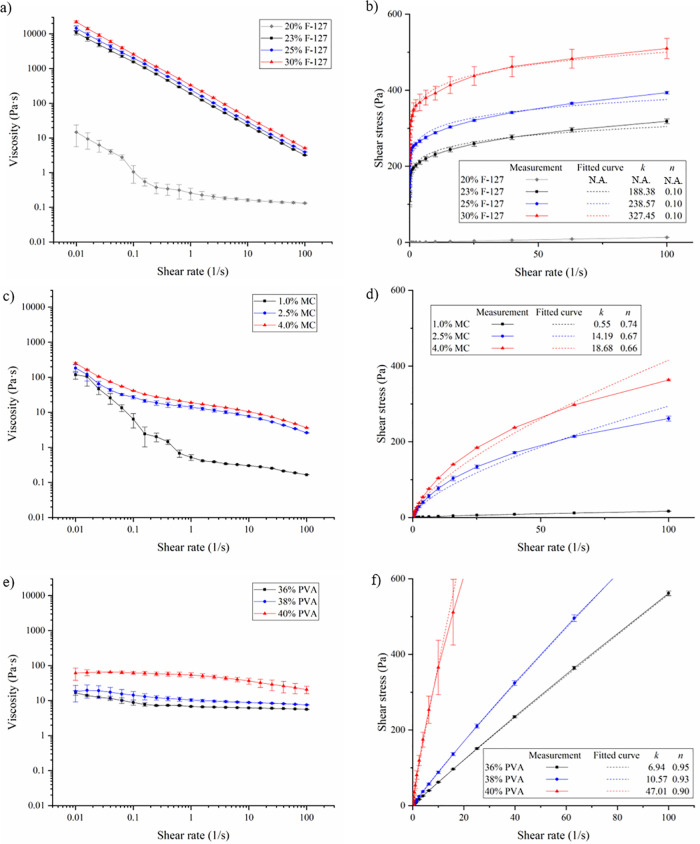

Figure 3 shows the viscosity and shear stress information of three different sacrificial inks, Pluronic F-127, MC, and PVA. A power-law model [ ] is used to fit the measured shear stress (τ)-shear rate ( ) curves, where k is the power-law consistency coefficient and n is the power-law flow behavior index. If n < 1, then the fluid is pseudoplastic and shear-thinning; if n = 1, the fluid is a Newtonian fluid; if n > 1, then the fluid is dilatant and shear-thickening. It is noted that the power-law model may not be the best constitutive model for these inks. For example, the Herschel–Bulkley model may be a better one for Pluronic F-127. The reason that the power-law model is adopted here is that it can reasonably capture their constitutive behavior, and the printability of these inks can be readily compared in terms of their model parameters (k and n).

FIG. 3.

Viscosity and shear stress results under steady shear of Pluronic F-127 (a) and (b), MC (c) and (d), and PVA (e) and (f). Error bars: ±one sigma.

As seen from Fig. 3, the viscosity of all three ink types increases with the concentration. The Pluronic F-127 (except the 20% ink) and MC inks are more shear-thinning, while the 20% Pluronic F-127 and all PVA ink are kind of Newtonian, and their n values are also estimated and presented in the figure. Since the 20% Pluronic F-127 ink is too fluidic for printing use, it was not further considered for the rest of the study.

For the Pluronic F-127 inks, their n value is the same (0.10). For the MC inks, their n value varies from 0.74 to 0.67 to 0.66, respectively; for the PVA inks, their n value varies from 0.95 to 0.93 to 0.90, respectively. For the MC and PVA inks, their n value decreases when their concentration increases, meaning more non-Newtonian.

B. Printability evaluation

The printability herein is evaluated based on the proposed feature printability (P) and feature diameter sensitivity (denoted as K) to the applied printing pressure.

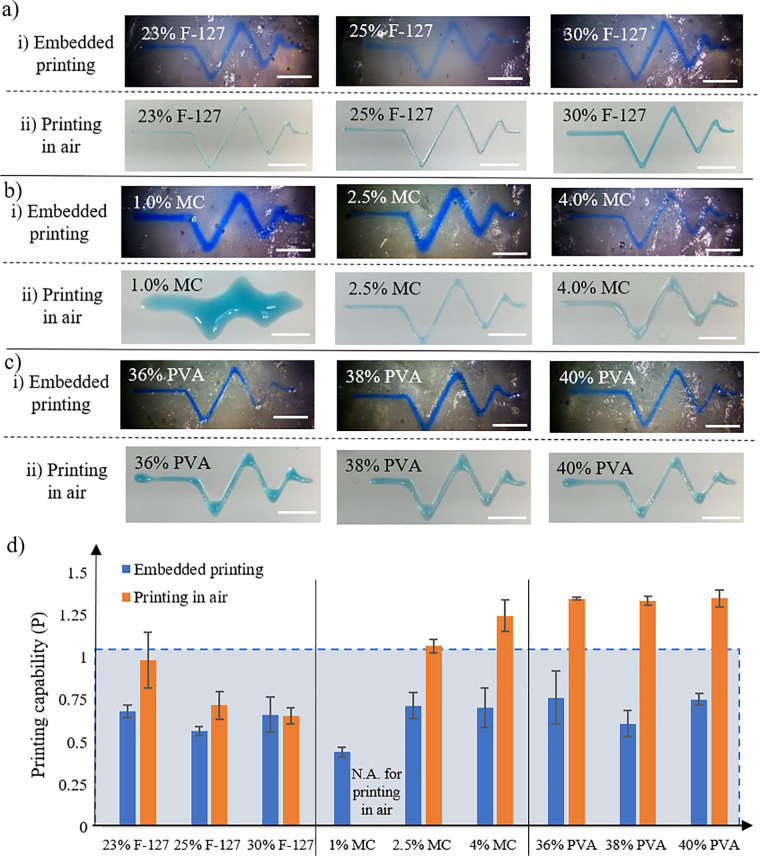

1. Printability in bath and in air

While the yield-stress property of the gelatin microgel-based matrix15 enables the embedded printing of various bioinks, it also improves the ink printability as seen from Fig. 4. For all the Pluronic F-127, MC, and PVA inks investigated in this study, they all show good printability and similar shape fidelity during embedded printing even that some of them may be not printable when printed in air as seen from Figs. 4(a)–4(c), and the printability value P decreases during embedded printing, showing improved printability, especially for the low concentration MC and PVA inks. When printing in air, only Pluronic F-127 inks can be printed well to capture each vertex; when printing in the yield-stress matrix bath, each ink can be printed well, indicating that the ink printability during embedded printing is different from that during printing in air due to the constraining effect of the matrix bath.

FIG. 4.

Evaluation of printability of (a) Pluronic F-127, (b) MC, and (c) PVA inks during pattern printing. The upper rows are based on embedded printing, and the lower rows are based on printing-in-air (scale bars: 5 mm). (d) Corresponding P values when embedded printing and printing in air (shaded area with P ≤ 1 means good printability). Error bars: ±one sigma.

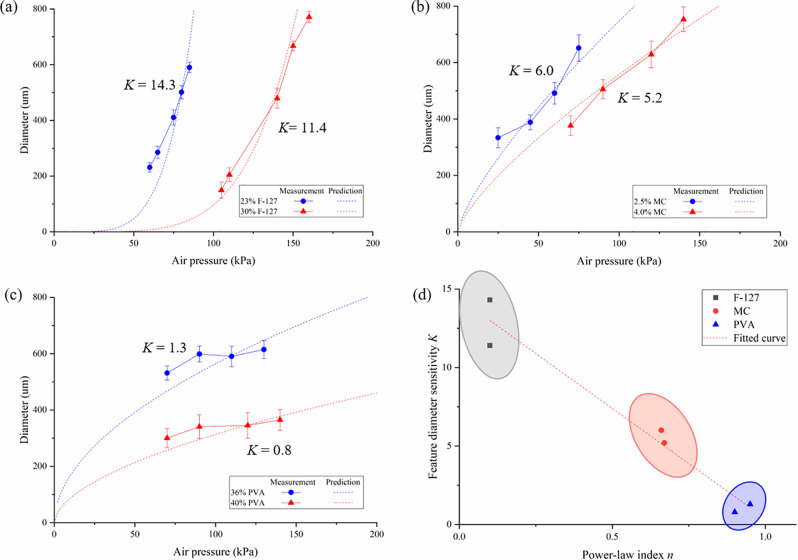

2. Feature diameter sensitivity to applied pressure

It is ideal to have different channel diameters by purely varying printing conditions, such as the applied pressure during embedded printing. The relationship between the filament diameter and air pressure was also investigated when the nozzle path speed was fixed at 2 mm/s. Herein, a sensitivity parameter K is introduced to describe this relationship, which is defined as the change of the printed diameter (μm) over the applied pressure (kPa), which is determined based on the curved fitted line as shown in Fig. 5. Two inks of each type were printed and evaluated: lowest and highest concentrations of the printable inks, and the 2.5% MC ink instead of the 1.0% MC ink was investigated as the lowest concentration ink since the latter was found to be too diffusive for the gelatin matrix bath. Of the six inks investigated, the Pluronic F-127 ink has the highest sensitivity to the applied pressure, followed by the MC and PVA inks [14.3 and 11.4 vs 6.0 and 5.2 vs 1.3 and 0.8 as seen from Figs. 5(a)–5(c)], and each lower concentration ink has higher sensitivity to the air pressure. In particular, the filament diameter of the 23% Pluronic F-127 ink increases from 231.1 μm to 590.2 μm when the air pressure varies from 60 to 85 kPa, showing a more than two-and-half fold increase in diameter. For the PVA inks [Fig. 5(c)], only a slight increase in diameter is observed as the pressure increases, meaning that the PVA filament is not sensitive to the applied pressure.

FIG. 5.

Filament diameter as a function of air pressure during embedded printing: (a) Pluronic F-127, (b) MC, and (c) PVA. (d) Relationship between the feature diameter sensitivity K and power-law flow behavior index n. Error bars: ±one sigma.

For a power-law fluid, the diameter of deposited filaments (df) can be estimated as follows:34

| (2) |

where R is the nozzle radius, L is the nozzle length, v is the path speed, and −Δp is the pressure drop. The predicted diameter based on this model is also shown in Fig. 5, showing good agreement. Assuming that the pressure drop is equal to the value of the applied pressure (ignore the buoyancy in the bath and the gravity of the ink), the filament diameter under varying air pressures can be predicted and is shown as the dashed curves in Fig. 5, respectively, by using the rheological measurements from Fig. 3 (k and n values), showing good agreement. For a given nozzle gauge and path speed, . Therefore, the filament diameter of a shear-thinning fluid (n < 1) is more sensitive to pressure than Newtonian fluids (n = 1). The dominant effect of n on k is also shown in Fig. 5(d) and further approximated using the following linear relationship:

| (3) |

For shear-thinning inks, a printing pressure increase results in a higher shear rate, which leads to a lower viscosity, meaning that more ink can be dispensed under the same pressure. As such, a higher shear-thinning ink (with a lower n value) has higher diameter sensitivity as seen from Eq. (3). It is concluded that inks with a shear-thinning property are capable of printing channels with a broad range of filaments by simply tuning the extrusion pressure, which may not be applicable to non-shear-thinning inks.

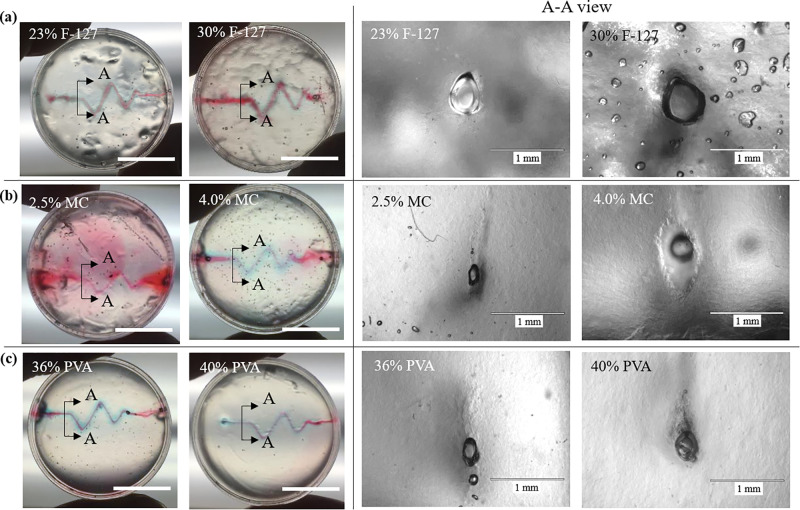

C. Removability evaluation

For the three sacrificial inks, the removal process was performed differently per their physical properties: thermal liquefaction for the Pluronic F-127 inks for their thermo-sensitive property and aqueous dissolution for the MC and PVA inks for their solubility in water. The deposited Pluronic F-127 inks can be liquefied and removed after simply cooling down, and the thermo-responsive test shows that the inks from 23% to 30% can change from the gel to sol state within 5 min at 4 °C to create perfusable channels as seen from Fig. 6(a). By immersing in a water bath, the MC and PVA inks can be easily removed too to create perfusable channels as seen from Figs. 6(b) and 6(c), respectively. No pronounced variance of the cross-sectional diameter is found at different straight side sections along the channel direction for each ink. It should be noted that the channel cross-sectional morphology of both the MC- and PVA-created channels are not as good as those by Pluronic F-127 in terms of circularity. This is attributed to their relatively low viscosity at zero shear rate after printing (order of 100 Pa·s vs 10 000 Pa·s of the Pluronic F-127 inks) in order to sustain their shape in the bath during the gelatin cross-linking period.

FIG. 6.

Sacrificial ink removal after printing: (a) Pluronic F-127, (b) MC, and (c) PVA. (Left) Perfusion of the created channels (blue: deposited ink; red: perfused dye; scale bars: 10 mm) and (right) cross-sectional views of the created channels after removal of the sacrificial inks.

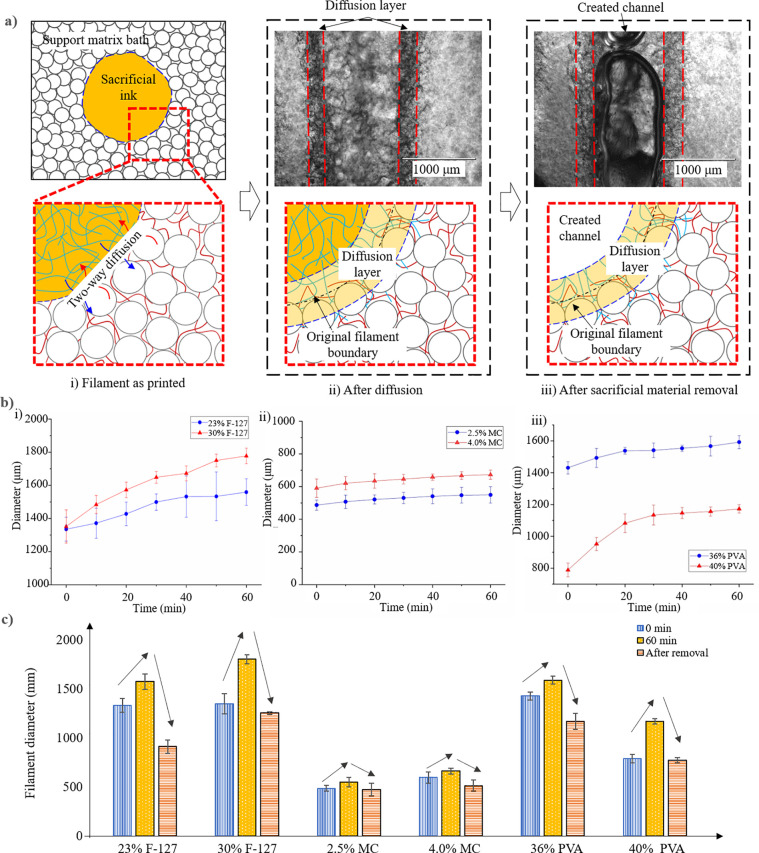

D. Diffusion-induced channel diameter variation

Since the gelatin composite matrix bath is composed of gelatin microgels and the gelatin precursor solution, a two-way diffusion happens between the hydrophilic sacrificial ink and gelatin solution phase. This may affect the ink removability and final channel size as during aqueous-in-aqueous printing35 due to the two-way diffusion process as illustrated in Fig. 7(a). The diffusion process starts right after a filament is printed: from the printed ink to the gelatin precursor solution and from the gelatin precursor solution to the printed ink [Fig. 7(a-i)]. After diffusion, the sacrificial ink and matrix bath are intermixed along the original filament boundary, thus forming a diffusion layer [Fig. 7(a-ii)]. The sacrificial ink removal process shows that the diffusion layer cannot be partially or completely removed [Fig. 7(a-iii)] depending on whether the diffused gelatin precursor solution is gelled at the ink removal moment.

FIG. 7.

Diffusion-induced filament/channel diameter variation: (a) schematic and images showing the diffusion and channel formation, (b) filament diameter variation as a function of post-printing time: (i) the Pluronic F-127 inks, (ii) the MC inks, and (iii) the PVA inks, and (c) Comparisons of feature diameter variations at 0 and 60 min, and after removal. Error bars: ±one sigma.

To evaluate the sacrificial ink diffusion-induced diameter variation of printed filaments, the filament diameter was measured over 60 min after printing. As shown in Fig. 7(b), the diameter of all deposited filaments increases over time due to the diffusion of sacrificial inks while the gelation precursor diffuses into the deposited ink filaments. The diameter increases are 18.3% ± 0.9%, 33.7% ± 0.7%, 12.8% ± 0.8%, 14.0% ± 0.6%, 11.2% ± 1.8%, and 48.7% ± 5.1%, respectively, for 23% Pluronic F-127, 30% Pluronic F-127, 2.5% MC, 4.0% MC, 36% PVA, and 40% PVA after 60 min post-printing. The rate difference is largely because of the diffusion coefficient of each ink in the gelatin solution; since the diffused inks stay in the matrix, they need to be at least biocompatible, if not biodegradable.

To investigate the effects of diffusion on the channel formation, the channel diameter after removing the sacrificial inks was also measured. The results are shown in Fig. 7(c) along with the measurements of the initial filament diameter. It is found that each channel diameter is smaller than the diameter of its counterpart, indicating that part of the filament is cross-linked due to the gelation of the diffused gelatin precursor, which is diffused from the matrix but left as part of the filament. In particular, the diameter of 23% Pluronic F-127-based channel may decrease by 31.5% (from the initial filament diameter), which is attributed to the high diffusion coefficient of the gelatin precursor with the 23% Pluronic F-127 ink. While the deposited sacrificial ink diffuses into the matrix bath after printing, its outskirt part is also mixed with the gelatin precursor diffused from the matrix bath. This outskirt part may turn unremovable if the diffused gelatin precursor gels as part of the sacrificial ink and has enough mechanical strength to survive from the removal process. As a result, the middle part of the deposited sacrificial ink is removed during the sacrificial ink removal step while the outskirt part stays with the matrix bath, resulting in a channel with a smaller diameter than that of the initially printed ink filament.

For the accurate control of channel diameter, it is expected that a sacrificial ink should be selected to have a small diffusion coefficient for cross-linkable material(s) of the matrix bath. A sacrificial ink should be selected to gel quickly or have a small diffusion coefficient for cross-linkable material(s) (gelatin precursor in this study) of the matrix bath to minimize the matrix material diffusion.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Printing performance during embedded printing

The printability results show that the ink printability during embedded printing is different from that during printing in air. Due to the existence of the yield-stress matrix bath, embedded printing may enhance the printability of some inks that are not printable in air as observed in this study. In particular, some low-viscosity inks can be printed since the supporting matrix bath used in embedded printing provides constraints to hold bioinks being deposited. As such, the general printability evaluation criteria are not applicable to embedded printing applications anymore. As a matter of fact, the selection of printable inks can be significantly broadened for embedded printing applications. In addition, printing in a yield-stress bath enables the freeform fabrication of 3D structures without the need for in situ cross-linking to retain their shape.15,27,36–39 In general, typical 3D printing approaches are layer-by-layer based, where a next layer is built on top of previously deposited layers and needs to be solidified in situ using a proper cross-linking mechanism. Fortunately, the omnidirectional support of yield-stress bath for deposited inks makes the in situ cross-linking requirement unnecessary if a 3D sacrificial structure is to be printed using embedded printing.

It should be noted that the filament formation process during embedded printing in a yield-stress matrix bath is different from that during conventional printing-in-air processes due to different supporting media (bath vs air). Broadly speaking, printing in air can be considered as a special case of printing in bath where the supporting material is air. In printing-in-air approaches, filaments are usually deposited directly in air and solidified in situ. The filament formation before cross-linking is in a liquid-in-air environment. The liquid–air interfacial surface tension and gravitational force significantly affect the morphology of deposited filaments. This emphasizes that the yield stress property contributes significantly to neutralizing the gravity and holding the shape when lacking any additional solidification mechanisms. During embedded printing, the supporting medium is the support bath, which is the gelatin composite-based yield-stress matrix bath in this study. The filament formation process occurs in a liquid-in-liquid environment, and the interfacial surface tension between the support bath and ink is usually negligible (for compatible material combinations such as the hydrophilic–hydrophilic combination). Instead, the filament formation process is affected by other material properties such as the shear elastic modulus of printed materials to ensure accurate deposition of bioinks and how fluidization of a support bath affects already deposited materials. Grosskopf et al.40 reported that the translating nozzle may cause dragging of the printed ink and displacement of the printed structure within a supporting matrix when the shear elastic modulus of the printed material is larger than that of the supporting matrix or when the yield stress of the supporting matrix is much lower than the viscous stresses. In general, several types of instabilities should be avoided during embedded printing,41,42 including: (1) crevice formation, (2) gravitational instability, (3) Rayleigh–Plateau instability, (4) Reynold's instability, and (5) diffusion, to name a few.

B. Selection of sacrificial ink materials for perfusable channel creation

1. Significance of the rheological properties of sacrificial ink materials

As observed from this study, typically considered rheological properties for 3D printing inks, such as the viscosity and surface tension range and yield-stress property, are not prerequisites for embedded printing applications. Therefore, general printability evaluation criteria are not applicable to embedded printing applications anymore. For the convenience of process implementation, the shear-thinning property may be of interest since the feature size can be easily tuned by controlling the applied printing pressure. In general, shear-thinning inks with a low n value are favorable for creating channels with spatially varying diameters.

2. Significance of matrix material diffusion on the final channel size

To minimize the channel diameter variation from the designed value, a sacrificial ink is expected to gel quickly after deposition and/or have a small diffusion coefficient for gelatin precursor to minimize the gelatin diffusion. As a sacrificial ink that is to be removed after printing, removal performance is one of the critical metrics for channel creation. It is expected that the diffused gelatin precursor may not have a too high concentration toward the center of deposited sacrificial filaments. For the part of low-concentration gelatin precursor within a deposited filament, the lightly gelled structure does not have enough strength to survive from the removal flow, leaving a perfusable channel. As such, it is preferred to choose a low gelatin precursor-diffusible sacrificial ink if the accurate control of channel morphology is of interest. This is particularly of consideration when fine printing features around 100 μm are of interest.

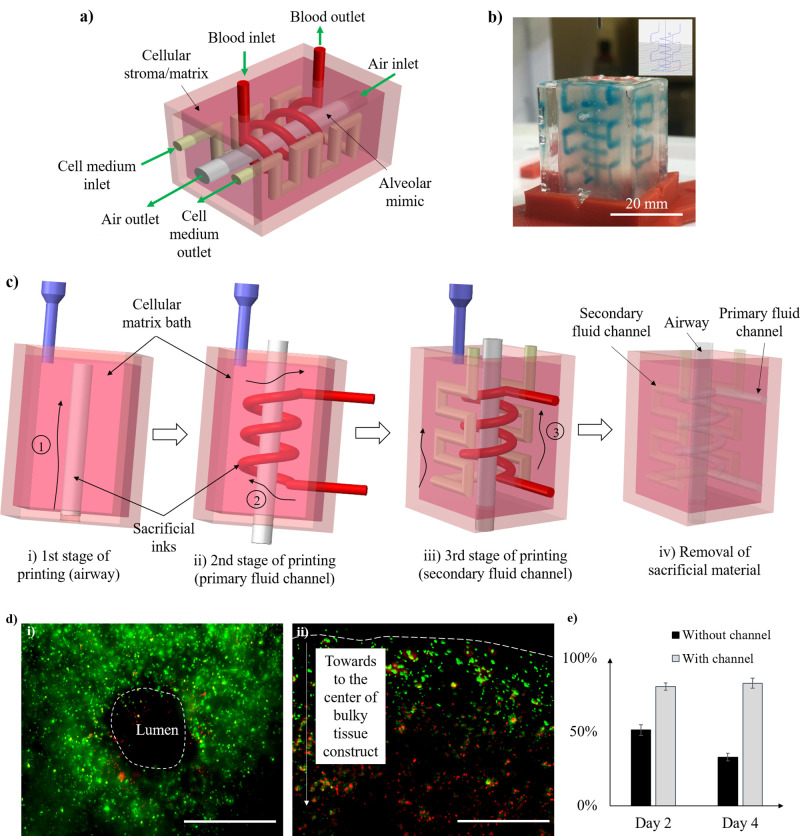

C. Feasibility demonstration

To test the feasibility of the sacrificial inks for embedded printing applications, a perfusable tissue model with three entangled channels is designed and fabricated to mimic the alveolar structure in the human lung. Figure 8(a) shows the detailed design of the three perfusable channels in the alveolar structure, which has an air channel to imitate alveoli, a primary fluid channel to imitate the blood vessel entangling the alveolar mimic, and a secondary fluid channel to provide mass transport channel for oxygen, nutrients, and wastes in a cellular matrix. For this study, all channels were perfused with cell media to demonstrate that the alveolar structure is a perfusable construct.

FIG. 8.

Fabrication of a perfusable tissue model: (a) schematic of the designed alveolar mimic, (b) the channel patterns after embedded printing in gelatin matrix (the sacrificial ink is dyed in blue, and the inset is the g-code path), (c) the schematics of the embedded printing process, and (d) fluorescence images of 3T3 cells in the tissue construct after culturing for 4 days [green (FDA) for live cells and red (EthD-1) for dead cells]: (i) with perfusable channels (dashed line: lumen) and (ii) without perfusable channel (dashed line: tissue block edge) (scale bars: 1000 μm), and (e) the cell viability of the groups without and with channels on day 2 and day 4.

The 23% Pluronic F-127 ink was used to construct the alveolar structure in the proposed gelatin composite matrix bath embedded with 3T3 cells. Figure 8(b) shows a printed tissue construct with a dyed sacrificial Pluronic F-127 ink before its removal, and Figs. 8(c-i)–8(c-iv) shows the step-by-step embedded printing process and subsequential sacrificial ink removal. Finally, the gelatin composite matrix is cross-linked under the enzymatic effect of TG and ready for cell medium perfusion.

Furthermore, the 3T3 cell viability is tested to show the cell medium delivery efficacy using the created perfusion channels. Figure 8(d) shows the representative images of 3T3 cells encapsulated in the gelatin composite matrix after 4-day culture; the living cells are shown in green, and the dead cells in red. The cells under dynamic culture show high viability [Fig. 8(d-i)] because the cell medium is continuously perfused through the channels, delivering much-needed oxygen and nutrients as well as removing the cell waste. However, for the bulky tissue construct without channels, the cell medium is unable to diffuse throughout the thick construct under the static culture condition, resulting in the low cell viability [Fig. 8(d-ii)]. The cell viability of the non-perfused group drops over time and is significantly lower than that of the perfused group {51.3% ± 3.7% vs 80.8% ± 2.5% on day 2 and 33.0% ± 2.6% vs 83.1% ± 3.5% on day 4 [Fig. 8(e)]}. The results illustrate the effectiveness of created perfusable channels for supporting thick tissue constructs.

V. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

Embedded bioprinting of sacrificial inks in a cross-linkable yield-stress matrix bath has emerged as a promising solution to fabricate perfusable channels that function as vasculature in 3D tissue constructs. The channel formation process depends on the shape fidelity of sacrificial inks during the embedded printing and post-printing sacrificial ink removal processes. Based on the printability and removability performance of three representative sacrificial inks [Pluronic F-127, methylcellulose (MC), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)] in a gelatin microgel-based composite matrix bath, some main conclusions can be drawn as follows. First, the ink printability during embedded printing is different from that during printing in air due to the constraining effect of the matrix bath, and general printability evaluation criteria are not applicable to embedded printing applications anymore. It should be noted that the channel cross-sectional morphology of both the MC- and PVA-created channels are not as good as those by Pluronic F-127 in terms of the circularity. Second, sacrificial inks with a shear-thinning property are capable of printing channels with a broad range of filaments by simply tuning the extrusion pressure, which may not be applicable to non-shear-thinning inks. The Pluronic F-127 ink has the highest sensitivity to the applied pressure of the six inks investigated, followed by the MC and PVA inks. In general, shear-thinning inks with a low n value are favorable for creating channels with spatially varying diameters. Finally, sacrificial inks with a low diffusion coefficient for cross-linkable matrix material(s) (gelatin precursor in this study) are desirable to minimize the post-printing channel diameter variation. Overall, this study offers better understanding of the use of sacrificial inks for channel creation in thick tissues, and the resulting knowledge may serve a guideline to refine the channel creation protocol and print better perfusable constructs/structures using embedded printing.

Future work may focus on: (1) the effect of yield-stress matrix bath on the filament formation during embedded printing, mainly in terms of its yield stress and viscoplastic behavior, and the prediction of deposited filament diameter using a suitable constitutive model and realistic printing environment such as the wall slip effect and matrix bath material properties, (2) the understanding of the post-printing two-way diffusion process in order to better develop sacrificial inks to minimize their diffusion into the gelatin solution if sacrificial inks are not biodegradable or even cytotoxic as well as the diffusion from the gelatin solution if the post-printing channel diameter variation is to be minimized, and (3) the development, perfusion, and evaluation of full-scale perfusable thick tissues with stroma cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported in this publication was partially supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (No. 1762941) and the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under Award No. UL1TR001427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The use of the Anton Paar rheometers is acknowledged.

APPENDIX: PREDICTION EQUATIONS PER FIG. 5

The prediction equations in Fig. 5 for each sacrificial ink are listed as follows:

| Ink materials | Equations (d in μm and Δp in kPa) |

|---|---|

| 23% Pluronic F-127 | |

| 30% Pluronic F-127 | |

| 2.5% MC | |

| 4.0% MC | |

| 36% PVA | |

| 40% PVA |

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bajaj P., Schweller R. M., Khademhosseini A., West J. L., and Bashir R., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 247–276 (2014). 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-105155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang Y., Leu M. C., Mazumder J., and Donmez A., J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 137, 014001 (2015). 10.1115/1.4028725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liew A. W. L. and Zhang Y., Int. J. Bioprint. 3(1), 3–17 (2017). 10.18063/IJB.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang Y. and Schmid S. R., J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 140, 094001 (2018). 10.1115/1.4040430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carmeliet P. and Jain R. K., Nature 407, 249–257 (2000). 10.1038/35025220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lovett M., Lee K., Edwards A., and Kaplan D. L., Tissue Eng., Part B 15(3), 353–370 (2009). 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Novosel E. C., Kleinhans C., and Kluger P. J., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 63(4–5), 300–311 (2011). 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Auger F. A., Gibot L., and Lacroix D., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 15, 177–200 (2013). 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Golden A. P. and Tien J., Lab Chip 7(6), 720–725 (2007). 10.1039/b618409j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang X. Y., Jin Z. H., Gan B. W., Lv S. W., Xie M., and Huang W. H., Lab Chip 14(15), 2709–2716 (2014). 10.1039/C4LC00069B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tocchio A., Tamplenizza M., Martello F., Gerges I., Rossi E., Argentiere S., Rodighiero S., Zhao W., Milani P., and Lenardi C., Biomaterials 45, 124–131 (2015). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller J. S., Stevens K. R., Yang M. T., Baker B. M., Nguyen D. H., Cohen D. M., Toro E., Chen A. A., Galie P. A., Yu X., Chaturvedi R., Bhatia S. N., and Chen C. S., Nat. Mater. 11(9), 768–774 (2012). 10.1038/nmat3357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kolesky D. B., Homan K. A., Skylar-Scott M. A., and Lewis J. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113(12), 3179–3184 (2016). 10.1073/pnas.1521342113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCormack A., Highley C. B., Leslie N. R., and Melchels F. P. W., Trends Biotechnol. 38(6), 584–593 (2020). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Compaan A. M., Song K., Chai W., and Huang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12(7), 7855–7868 (2020). 10.1021/acsami.9b15451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song K. H., Highley C. B., Rouff A., and Burdick J. A., Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(31), 1801331 (2018). 10.1002/adfm.201801331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Highley C. B., Song K. H., Daly A. C., and Burdick J. A., Adv. Sci. 6(1), 1801076 (2019). 10.1002/advs.201801076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skylar-Scott M. A., Uzel S. G., Nam L. L., Ahrens J. H., Truby R. L., Damaraju S., and Lewis J. A., Sci. Adv. 5(9), eaaw2459 (2019). 10.1126/sciadv.aaw2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun J., Li Y., Liu G., Chen S., Zhang Y., Chen C., Chu F., and Song Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12(19), 22108–22114 (2020). 10.1021/acsami.0c01138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang J., Bao B., Li M., Sun J., Zhang C., Li Y., Li F., Yao X., and Song Y., Adv. Mater. 28(7), 1420–1426 (2016). 10.1002/adma.201503682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jungst T., Smolan W., Schacht K., Scheibel T., and Groll J., Chem. Rev. 116(3), 1496–1539 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mandrycky C., Wang Z., Kim K., and Kim D. H., Biotechnol. Adv. 34(4), 422–434 (2016). 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fitzsimmons R. E., Aquilino M. S., Quigley J., Chebotarev O., Tarlan F., and Simmons C. A., Bioprinting 9, 7–18 (2018). 10.1016/j.bprint.2018.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Z., Jin Y., Yin J., Xu C., Xiong R., Christensen K., Ringeisen B. R., Chrisey D. B., and Huang Y., Appl. Phys. Rev. 5(4), 041304 (2018). 10.1063/1.5053979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bertassoni L. E., Cecconi M., Manoharan V., Nikkhah M., Hjortnaes J., Cristino A. L., Barabaschi G., Demarchi D., Dokmeci M. R., Yang Y., and Khademhosseini A., Lab Chip 14(13), 2202–2211 (2014). 10.1039/C4LC00030G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee W., Lee V., Polio S., Keegan P., Lee J. H., Fischer K., Park J. K., and Yoo S. S., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 105(6), 1178–1186 (2010). 10.1002/bit.22613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu W., DeConinck A., and Lewis J. A., Adv. Mater. 23(24), H178–183 (2011). 10.1002/adma.201004625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolesky D. B., Truby R. L., Gladman A. S., Busbee T. A., Homan K. A., and Lewis J. A., Adv. Mater. 26(19), 3124–3130 (2014). 10.1002/adma.201305506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahlfeld T., Kohler T., Czichy C., Lode A., and Gelinsky M., Gels 4(3), 68 (2018). 10.3390/gels4030068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu M., Dailamy A., Lei X. Y., Parekh U., McDonald D., Kumar A., and Mali P., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 7(23), e1800845 (2018). 10.1002/adhm.201800845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schuurman W., Levett P. A., Pot M. W., van Weeren P. R., Dhert W. J., Hutmacher D. W., Melchels F. P., Klein T. J., and Malda J., Macromol. Biosci. 13(5), 551–561 (2013). 10.1002/mabi.201200471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Song K., Compaan A. M., Chai W., and Huang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 22453–22466 (2020). 10.1021/acsami.0c01497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu C., Chai W., Huang Y., and Markwald R. R., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109(12), 3152–3160 (2012). 10.1002/bit.24591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chhabra R. P. and Richardson J. F., Non-Newtonian Flow and Applied Rheology: Engineering Applications ( Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muth J. T., Vogt D. M., Truby R. L., Menguc Y., Kolesky D. B., Wood R. J., and Lewis J. A., Adv. Mater. 26(36), 6307–6312 (2014). 10.1002/adma.201400334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hinton T. J., Jallerat Q., Palchesko R. N., Park J. H., Grodzicki M. S., Shue H. J., Ramadan M. H., Hudson A. R., and Feinberg A. W., Sci. Adv. 1(9), e1500758 (2015). 10.1126/sciadv.1500758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin Y., Compaan A., Chai W., and Huang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(23), 20057–20066 (2017). 10.1021/acsami.7b02398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jin Y., Chai W., and Huang Y., Mater. Sci. Eng., C 80, 313–325 (2017). 10.1016/j.msec.2017.05.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Compaan A. M., Song K., and Huang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(6), 5714–5726 (2019). 10.1021/acsami.8b13792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grosskopf A. K., Truby R. L., Kim H., Perazzo A., Lewis J. A., and Stone H. A., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(27), 23353–23361 (2018). 10.1021/acsami.7b19818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O'Bryan C. S., Bhattacharjee T., Niemi S. R., Balachandar S., Baldwin N., Ellison S. T., Taylor C. R., Sawyer W. G., and Angelini T. E., MRS Bull. 42(8), 571–577 (2017). 10.1557/mrs.2017.167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen S., Tan W. S., Juhari M. A. B., Shi Q., Cheng X. S., Chan W. L., and Song J., Biomed. Eng. Lett. 10, 453–479 (2020). 10.1007/s13534-020-00171-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.