Abstract

Host inflammatory responses predict worse outcome in severe pneumonia, yet little is known about what drives dysregulated inflammation. We performed metagenomic sequencing of microbial cell-free DNA (mcfDNA) in 83 mechanically-ventilated patients (26 culture-positive, 41 culture-negative pneumonia, 16 uninfected controls). Culture-positive patients had higher levels of mcfDNA than those with culture-negative pneumonia and uninfected controls (p<0.005). Plasma levels of inflammatory biomarkers (fractalkine, procalcitonin, pentraxin-3 and suppression of tumorigenicity-2) were independently associated with mcfDNA levels (adjusted p<0.05) among all patients with pneumonia. Such host-microbe interactions in the systemic circulation of patients with severe pneumonia warrant further large-scale clinical and mechanistic investigations.

Keywords: Pneumonia, Infections, Host-microbe interaction

Variability in host inflammatory response has emerged as a key predictor of outcome in critically-ill patients.[1] Elevated biomarkers of host innate immunity and inflammation upon admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) have been consistently associated with worse outcomes in patients with severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[1,2] Little is known about the specific stimuli and triggers of this exuberant inflammatory response, but recent research implicates variation in the lung microbiome in patients with acute respiratory failure. Low community diversity and high abundance of pathogenic bacteria in the respiratory tract correlate with elevated inflammatory biomarkers and worse clinical outcomes.[3] It is unclear whether this early systemic inflammatory response reflects local interactions between microbes and immune cells in the alveolar space, or systemic activation of innate immunity from circulating pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that leak from the injured alveolar epithelium. Such distinction is important for understanding the pathogenesis of severe pneumonia and clarifying causal mechanisms for circulating PAMPs.

The advent of ultra-sensitive, plasma metagenomic sequencing for circulating microbial cell-free DNA (mcfDNA) [4] offers the opportunity to study the impact of a well-known PAMP (mcfDNA) on systemic host-responses in pneumonia. We hypothesized that patients with severe pneumonia with higher levels of mcfDNA would exhibit intensified inflammatory responses.

METHODS

We conducted a nested case-control study of mechanically-ventilated patients with and without severe pneumonia from an ICU cohort.[2,3,5] Based on consensus review of all available clinical data, we retrospectively diagnosed patients with community vs. hospital-acquired pneumonia [6], and as culture-positive (when pathogenic microbial species were isolated from respiratory specimens or blood cultures) vs. culture-negative (when there was no growth in neither culture, or only normal respiratory flora were reported in respiratory cultures). We quantified the radiologic severity index (RSI) on the first available chest radiograph post-intubation and calculated clinical pulmonary infection scores (CPIS) from available data.[7,8] We conducted plasma mcfDNA metagenomics with the Karius Test [Karius Inc., CA]. We measured nine host-response biomarkers and classified patients in a hyper- vs. hypoinflammatory subphenotype (Supplemental Methods). Metagenomic sequences were quantified as mcfDNA molecules per microliter (MPMs). We compared clinical variables, biomarker and mcfDNA levels between the three clinical groups (culture-positive vs. culture-negative pneumonia, and uninfected controls) with non-parametric tests. We examined associations between biomarkers and mcfDNA concentration with linear regression models (Supplemental Methods).

RESULTS

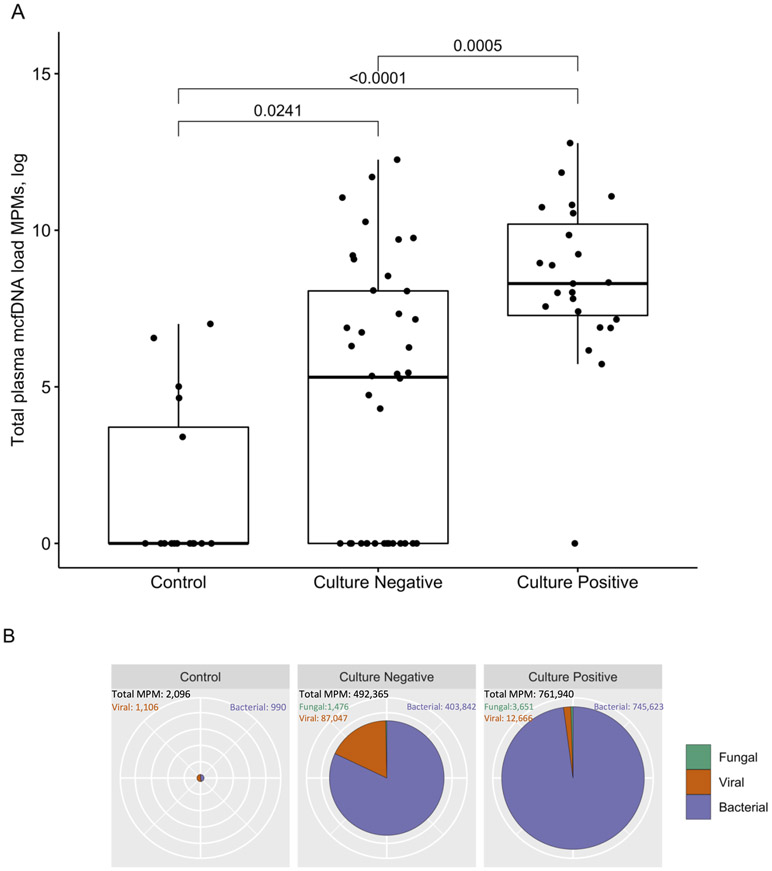

We examined 26 patients with culture-positive pneumonia, 41 patients with culture-negative pneumonia, and 16 uninfected controls (Table 1). Patients with pneumonia (culture-positive or negative) had fewer ventilator-free days, higher CPIS, RSI, and levels of inflammatory biomarkers compared to controls (Table 1, p<0.05). Culture-positive subjects had higher circulating mcfDNA compared to other groups (p<0.05, Figure 1A). Of the 23 culture-positive subjects with detectable mcfDNA in plasma, only three (13%) were bacteremic. There were no significant differences in plasma mcfDNA levels between patients diagnosed with hospital- vs. community-acquired pneumonia (Figure S1). The majority (92%) of all detected mcfDNA sequences belonged to bacteria (Figure 1B) and 64% of sequences were assigned to established respiratory pathogens (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Table S1, Figure S2). A comparison between mcfDNA sequencing and culture results is shown in Table S2. We did not detect any significant effect of timing of sample acquisition or antibiotic exposure prior to sampling on mcfDNA load (Figure S3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, outcomes, host response biomarkers and quantitative results of microbial cell-free DNA sequencing by clinical diagnosis.

| Uninfected controls# (n=16) |

Culture-negative pneumonia (n=41) |

Culture-positive pneumonia (n=26) |

P-value for comparisons between all 3 subgroups |

P-value for culture -positive vs negative pneumonia |

P-value for comparisons between pneumonia vs controls |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median [IQR], yrs) | 56.2 [44.2, 69.4] | 54.2 [41.7, 69.8] | 57.1 [52.1, 62.4] | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.92 |

| Male, N (%) | 12 (75.0) | 22 (53.7) | 18 (69.2) | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.39 |

| COPD, N (%) | 1 ( 6.2) | 6 (14.6) | 7 (26.9) | 0.23 | 0.51 | 0.29 |

| Immunosuppression, N (%) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (15.0) | 9 (34.6) | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1.00 |

| BMI (median [IQR], kg/m2) | 27.7 [23.3, 29.7] | 29.1 [26.6, 34.1] | 25.4 [22.1, 32.5] | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 1 (6.2) | 18 (43.9) | 9 (34.6) | 0.0202 | 0.61 | 0.0087 |

| CPIS (median [IQR]) | 2.0 [1.0, 4.0] | 6.0 [6.0, 7.0] | 8.0 [7.0, 8.0] | <0.0001 | 0.0271 | <0.0001 |

| RSI (median [IQR]) | 4.0 [1.5, 15.5] | 33.0 [20.5, 49.5] | 17.0 [8.0, 28.0] | 0.0001 | 0.0070 | 0.0015 |

| SOFA score$ (median [IQR]) | 5.0 [3.0, 7.5] | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] | 6.0 [4.0, 8.0] | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.19 |

| HAP, N (%) | NA | 11 (26.8) | 8 (30.8) | NA | 0.83 | NA |

| ARDS, N(%) | NA | 17 (41.5) | 3 (11.5) | NA | 0.0129 | NA |

| VFD (median [IQR], days) | 24.0 [21.8, 25.3] | 18.0 [0.0, 24.0] | 17.0 [11.2, 22.8] | 0.0036 | 0.57 | 0.0009 |

| Mortality at 30 days, N (%) | 1 ( 6.2) | 11 (26.8) | 4 (15.4) | 0.21 | 0.56 | 0.18 |

| Hypoinflammatory subphenotype, N (%) | 15 (93.8) | 38 (95.0) | 19 (73.1) | 0.0293 | 0.07 | 0.68 |

| Plasma biomarkers, pg/mL | ||||||

| Procalcitonin (median [IQR]) | 218.5 [80.8, 358.6] | 607.5 [187.5, 1787.9] | 1569.0 [423.3, 4040.7] | 0.0035 | 0.07 | 0.0046 |

| Pentraxin-3 (median [IQR]) | 1068.8 [578.1, 2446.0] | 3412.8 [1596.6, 6594.2] | 6974.1 [2866.6, 11836.7] | 0.0008 | 0.06 | 0.0011 |

| IL-6 (median [IQR]) | 24.6 [16.2, 50.6] | 31.5 [10.8, 100.4] | 67.0 [30.4, 186.4] | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| IL-8 (median [IQR]) | 10.7 [6.8, 13.9] | 13.3 [7.1, 23.4] | 24.5 [10.7, 43.2] | 0.0316 | 0.12 | 0.0500 |

| Ang-2 (median [IQR]) | 4030.3 [2298.1, 4667.2] | 4897.9 [3275.6, 10374.3] | 7818.7 [3387.8, 13765.0] | 0.0184 | 0.49 | 0.0061 |

| ST-2 (median [IQR]) | 46629.3 [22641.9, 149493.9] | 117878.2 [54886.1, 255883.2] | 185459.4 [101065.5, 626255.4] | 0.0045 | 0.15 | 0.0032 |

| RAGE (median [IQR]) | 1688.9 [1346.2, 3205.4] | 2701.2 [1661.4, 5673.3] | 4050.3 [2304.9, 7019.0] | 0.0058 | 0.14 | 0.0045 |

| TNFR1 (median [IQR]) | 2398.7 [1300.8, 3336.2] | 2892.5 [2197.3, 5511.8] | 3955.3 [2305.2, 9087.0] | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.0262 |

| Fractalkine (median [IQR]) | 841.4 [410.1, 1231.9] | 1305.2 [410.1, 2217.9] | 1652.9 [910.4, 2809.1] | 0.0387 | 0.22 | 0.0292 |

| McfDNA Sequencing Results | ||||||

| Total plasma mcfDNA (median [IQR], MPM) | 0.0 [0.0, 48.5] | 202.0 [0.0, 3174.8] | 4015.0 [1461.0, 28435.5] | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 |

| Bacterial mcfDNA (median [IQR]) | 0.0 [0.0, 7.5] | 0.0 [0.0, 1053.5] | 4015.0 [1131.5, 24113.5] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0033 |

| Viral mcfDNA (median [IQR], MPM) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

| Fungal mcfDNA (median [IQR], MPM) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Presence of respiratory pathogen mcfDNA, N (%) | 1 (6.2) | 16 (40.0) | 21 (91.3) | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 |

| Respiratory pathogen mcfDNA (median [IQR], MPM) ^ | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 1104.5] | 2986.0 [626.0, 12718.5] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| McfDNA of microbes with unclear clinical importance (median [IQR], MPM) ^ | 0.0 [0.0, 7.5] | 0.0 [0.0, 877.3] | 594.0 [0.0, 1175.5] | 0.0396 | 0.16 | 0.0341 |

Data are presented as median with interquartile ranges for continuous variables and N with percentage for categorical variables. P-values for comparisons between the three clinical categories were obtained from Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and from Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. P-values for the comparison between patients with culture-positive vs. −negative pneumonia were adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini-Hochberg correction post-hoc from three group comparisons. P-values for the comparisons between patients with pneumonia (both culture-positive and negative) vs. controls were obtained from Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and from Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Among the 16 uninfected controls, 12 (75%) subjects were intubated for airway protection without any evidence of respiratory infection, and the remaining 4 (25%) subjects were intubated for cardiogenic pulmonary edema from decompensated congestive heart failure.

SOFA score calculation did not include the neurologic component, as all patients were intubated and receiving sedative medications, which impaired our ability to perform assessment of Glasgow Coma Scale in a consistent and reproducible manner.

Detailed classification of mcfDNA belonging to recognized respiratory pathogens vs. microbes of unclear clinical importance is provided in Table S1.

Ang, angiopoietin; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPIS, clinical pulmonary infection score; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; IL, interleukin; IQR, interquartile range; mcfDNA, microbial cell-free DNA; MPM, microbial cell-free DNA per microliter of plasma; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; RSI, radiologic severity index; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; ST-2, suppression of tumorgenicity-2; TNFR-1, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1; VFD, ventilator free day.

Figure 1: Plasma microbial cell-free DNA levels are elevated in culture-positive pneumonia compared with culture-negative pneumonia and uninfected controls.

A: Patients with culture-positive pneumonia had higher levels of plasma mcfDNA Molecules per Microliter (MPMs) compared to patients with culture-negative pneumonia, who in turn had also higher plasma mcfDNA levels compared to uninfected controls (pairwise comparisons post hoc adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg method).

B: Types of mcfDNA (bacterial, fungal or viral) detected in culture-positive, culture-negative pneumonia and in uninfected controls. The radius of pie charts scales quadratically proportional to the sum of mcfDNA MPMs detected within each patient subgroup. The proportion of viral mcfDNA was significantly higher in the culture-negative (17.7%) compared to the culture-positive pneumonia (1.7%) group (p<0.0001 for z test of comparison of proportions).

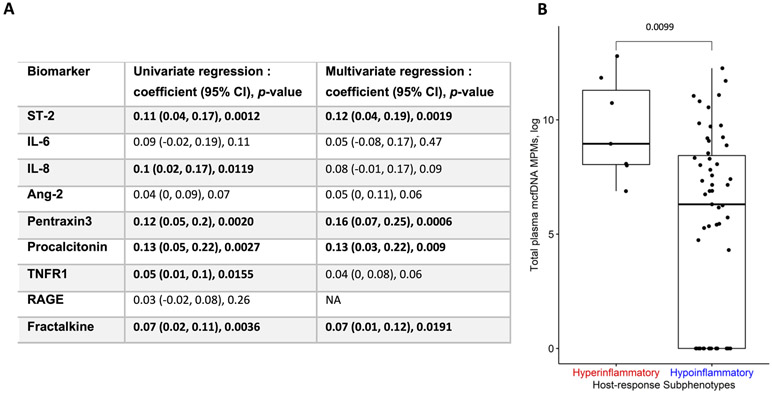

As for host response, in univariate regression models of biomarkers against mcfDNA in patients with pneumonia, we detected significant associations for fractalkine, interleukin-8, procalcitonin, pentraxin-3, suppression of tumorigenicity-2 (ST-2), and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFR-1) levels (all p<0.05, Figure 2A). In multivariate regression models, the associations for fractalkine, procalcitonin, pentraxin-3 and ST-2 remained statistically significant (Figure 2A). Patients with pneumonia assigned to the adverse hyperinflammatory subphenotype (n=9, 13%) had significantly higher mcfDNA levels compared to hypoinflammatory patients (p<0.01, Figure 2B). Stratified analyses by mcfDNA category (recognized respiratory pathogens vs microbes of unclear clinical importance, Table S1) revealed significant associations with the hyperinflammatory subphenotype (Figure S4) and culture-positivity (Figure S5) for mcfDNA belonging to respiratory pathogens only.

Figure 2: Circulating mcfDNA is associated with host inflammatory responses in patients with pneumonia. A. Linear regression results for association between microbial cell-free DNA (mcfDNA) and host response biomarkers.

We built linear regression models of plasma biomarkers (outcomes) against plasma mcfDNA levels (predictor) in unadjusted as well as adjusted models for a priori selected potential confounders: i) a surrogate of the microbial inoculum (culture-positive vs. negative classification), ii) degree of lung injury as depicted radiographically by radiographic severity index (RSI) and by the epithelial injury biomarker receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE), and iii) host innate immunity status (age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and immunosuppression). Estimated regression coefficient, 95% confidence intervals and p-values for significance of mcfDNA MPMs for each regression model are reported.

B. Patients with pneumonia assigned to the hyperinflammatory subphenotype had significantly higher mcfDNA compared to hypoinflammatory patients (median 7,731, interquartile range-IQR, MPMs, [3,100-79,849] vs. 546 [0-4,609] respectively, p<0.05). We assigned patients to the hyper- vs. hypo-inflammatory subphenotype based on a parsimonious predictive model utilizing levels of angiopoietin-2, procalcitonin, TNFR1 and bicarbonate (see supplemental methods).

Ang-2, angiopoietin-2; CI, confidence interval; IL, interleukin; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end product; ST-2, suppression of tumorigenicity-2; TNFR-1, tumour necrosis factor receptor 1.

DISCUSSION

Our study reveals a novel link between circulating mcfDNA and systemic inflammation in patients with severe pneumonia, suggesting a biologically plausible microbe-host interaction in the systemic circulation. In our relatively small, but carefully phenotyped cohort, we demonstrate that circulating mcfDNA accounts, at least in part, for the intensified inflammatory host-responses, which have been reproducibly associated with worse clinical outcomes in severe pneumonia.[2] The discovery of a higher mcfDNA load in patients assigned to the hyperinflammatory subphenotype adds additional resolution in linking microbiota and patient-level outcomes.

Study of mcfDNA in the systemic circulation has been challenging due to the extremely small ratio of microbial to human cfDNA in blood samples, even in the presence of bacteremia. Methodological advancements have enabled the sequencing of circulating mcfDNA, which may assist in non-invasive clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, as shown by Langelier et al. who identified one or more confirmed pneumonia pathogens in 12/18 (67%) of critically-ill patients with pneumonia.[9] Similarly, we detected mcfDNA of respiratory pathogens in 91% and 40% of culture-positive and -negative patients, respectively. Nonetheless, the clinical utility of plasma metagenomics in improving clinical decision making and patient outcomes remains to be demonstrated by prospective studies. Furthermore, a multi-compartment study of microbiota and barrier function would help clarify whether circulating microbes (or their fragments) invade through the injured alveolar epithelium or leak through a disrupted intestinal mucosal barrier.

Notably, the significant associations between mcfDNA and fractalkine, procalcitonin, pentraxin-3 and ST-2 were independent of our radiographic (RSI) and biomarker (RAGE) measurements of the degree of lung injury. McfDNA is an established PAMP that can stimulate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in innate immune cells to activate downstream inflammatory signaling.[10] Other microbial PAMPs, like beta-D-Glucan, flagellin or lipopolysaccharide, may also leak in the systemic circulation and directly activate PRRs.

With ongoing efforts to understand differential outcomes in critically-ill patients, it is important to unravel proximal, biological determinants of the clinical subphenotypes for directing personalized therapeutic interventions. Our findings of plausible host and microbe interactions in the systemic circulation of patients with severe pneumonia warrant further large-scale clinical and mechanistic investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank the patients and patient families that have enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh Acute Lung Injury Registry. We also thank the physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists and other staff at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian and Shadyside Hospital intensive care units for assistance with coordination of patient enrollment and collection of patient samples. We would also like to thank Caitlin Schaefer MPH for her help with clinical data extraction.

Funding information:

National Institute of Health [K23-KL139987-03 (GDK), P01-HL114453-07(BM)]; Karius Inc. (GDK)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statements: GDK has received research funding from Karius Inc.; GH received research funding from Karius Inc. AA, LB, SD and SB are employed by Karius Inc.; BM receives research funding from Bayer Pharmaceuticals Inc.; the other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics approval statement: This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (protocol STUDY19050099). Written informed consent was provided by all participants or their surrogates in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability statement:

To ensure transparency and reproducibility of our study, we will release our de-identified dataset and code for analyses on GitHub upon acceptance of publication.

References

- 1.Reddy K, Sinha P, O’Kane CM, et al. Subphenotypes in critical care: translation into clinical practice. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:631–643. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitsios GD, Yang L, Manatakis DV, et al. Host-Response Subphenotypes Offer Prognostic Enrichment in Patients With or at Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med 2019;47:1724–1734. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitsios GD, Yang H, Yang L, et al. Respiratory Tract Dysbiosis Is Associated with Worse Outcomes in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:1666–1677. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201912-2441OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blauwkamp TA, Thair S, Rosen MJ, et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:663–674. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0349-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitsios G, Yang L, Nettles R, et al. 245. Plasma and Respiratory Specimen Metagenomic Sequencing for the Diagnosis of Severe Pneumonia in Mechanically-Ventilated Patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:S138–S138. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz360.320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, et al. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165566.82925.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: the clinical pulmonary infection score as a surrogate for diagnostics and outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51 Suppl 1:S131–5. doi: 10.1086/653062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheshadri A, Godoy M, Erasmus JJ, et al. Progression of the Radiologic Severity Index is associated with increased mortality and healthcare resource utilisation in acute leukaemia patients with pneumonia. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019;6:e000471. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langelier C, Fung M, Caldera S, et al. Detection of Pneumonia Pathogens from Plasma Cell-Free DNA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:491–495. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201904-0905LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009;22:240–73, Table of Contents. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To ensure transparency and reproducibility of our study, we will release our de-identified dataset and code for analyses on GitHub upon acceptance of publication.