Abstract

Introduction:

Women’s decision-making autonomy has a positive effect on the scale-up of contraceptive use. In Ethiopia, evidence regarding women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use and associated factors is limited and inconclusive. Therefore, this study was intended to assess married women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use and associated factors in Ethiopia using a multilevel logistic regression model.

Methods:

The study used data from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey that comprised of a weighted sample of 3668 married reproductive age women (15–49 years) currently using contraceptives. A multilevel logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors affecting married women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Akaike’s information criterion was used to select the best-fitted model.

Results:

Overall, 21.6% (95% confidence interval = 20.3%–22.9%) of women had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Community exposure to family planning messages (adjusted odds ratio = 2.22, 95% confidence interval = 1.67–3.05), media exposure (adjusted odds ratio = 2.13, 95% confidence interval = 1.52–3.23), age from 35 to 49 years (adjusted odds ratio = 2.09, 95% confidence interval = 1.36–4.69), living in the richer households (adjusted odds ratio = 1.67, 95% confidence interval = 1.32–3.11), and visiting health facility (adjusted odds ratio = 2.01, 95% confidence interval = 1.34–3.87) were positively associated with women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. On the contrary, being Muslim (adjusted odds ratio = 0.53, 95% confidence interval = 0.29–0.95), being married before the age of 18 years (adjusted odds ratio = 0.33, 95% confidence interval = 0.12–0.92), and residing in rural residence (adjusted odds ratio = 0.48, 95% confidence interval = 0.23–0.87) were negatively associated with women’s independent decision on contraceptive use.

Conclusion:

Less than one-fourth of married reproductive age women in Ethiopia had the decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Media exposure, women’s age, household wealth, religion, age at marriage, visiting health facilities, community exposure to family planning messages, and residence were the factors associated with women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. The government should promote women’s autonomy on contraceptive use as an essential component of sexual and reproductive health rights through mass media, with particular attention for adolescent women, women living in households with poor wealth, and those residing in rural settings.

Keywords: Associated factors, contraceptive use, Ethiopia, married women, multilevel analysis, women’s autonomy

Introduction

Women’s decision-making autonomy is the ability of women to decide independently on their concerns. 1 Women’s independent decision on reproductive health issues is crucial for better maternal and child health outcomes; however, restriction of open discussion between couples due to gender-based power inequalities limits women’s access to reproductive health services, particularly contraceptives. 2 Women’s autonomy on the decision regarding health increases women’s access to health information and utilization of reproductive services. 3 A previous study showed that women’s decision-making autonomy was associated with an increase in contraceptive use by 70%. 4 Other studies also revealed a higher prevalence of contraceptive use among women who had decision-making autonomy.5–7 In addition, women’s decision-making autonomy is linked with other dimensions of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) like unmet family planning need, 3 unintended pregnancy,8,9 and sexual behavior. 10

Studies have shown that women are less autonomous on the decision regarding contraceptive use and other SRH issues due to cultural influence at the community level and male dominance at the household level.11,12 In developing countries, the proportion of women independently deciding on contraceptive use is low.3,13,14 According to the 2017 estimates, 63% of married women use contraceptives worldwide and 32% of women utilize these services in Africa 15 with huge regional variations. In Ethiopia, only 35% of reproductive age women use some form of fertility control methods. 16

Studies in different parts of Africa have reported women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use as one of the socio-cultural factors affecting the uptake of contraceptive services.4–7,10,17–23 However, women’s low status due to deep-rooted socio-cultural barriers and gender norms hinder them to have decision-making autonomy on their SRH issues. 24 It was reported that only 55% of married women in the globe had decision-making autonomy on SRH issues, with 36% in Sub-Saharan Africa. 25 About 6% 3 and 41.3% 26 of married women in Senegal and South Africa, respectively, had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. In Ethiopia, evidence shows a significant variation in the level of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use across different geographical areas that ranges from 22% to 80%.27–33

Studies conducted previously have identified different community and individual-level factors affecting women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. These include place of residence, 33 age,13,30,33,34 household wealth index, 13 women’s education14,29,32,34 and occupation,13,14,32,33 women’s knowledge about contraceptive,30,31,35 religion, 14 and number of living children. 33

Different strategies, policies, and programs have been implemented to improve safe motherhood at global, regional, and national levels. For instance, the International Conference for Population Development (ICPD) recognition of the SRH rights in 1994 was subsequently supported by the 2000 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as the global movement toward achieving universal health coverage. 36

In Ethiopia, laws and policy revisions were undertaken as the responses to international conventions and human rights agreements highlighted in ICPD, MDGs, and SDGs. Promoting the use of SRH services and information, 37 legalization of women’s rights to information and rights to be protected from the risk of unwanted pregnancy, 38 and implementation of a 5-year Health Sector Transformation Plan strategies37,39 were the efforts taken to improve reproductive health. In Ethiopia, despite the regulations and strategies taken to strengthen SRH and related rights, women still have little autonomy over their decision to use the available contraceptive methods to avoid unintended pregnancies. 40

Studies conducted regarding women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use are still highly variable and inconclusive. Furthermore, both individual- and community-level factors affecting women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use are not yet addressed at the national level that will help the policy and decision-makers to develop appropriate intervention tools based on evidence. Hence, this study was aimed to assess the level of married women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use and its associated factors in Ethiopia using a mixed-effect logistic regression model.

Methods and materials

Data source, study period, study design, and procedures

Secondary analysis of cross-sectional data was performed after the data were retrieved from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program official database website (http://dhsprogram.com), which was collected from 18 January to 27 June 2016. The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) is a nationally representative survey conducted every 5 years in the nine regional states (Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambela, Harari, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR), and Tigray), and two administrative cities (Addis Ababa and Dire-Dawa) of Ethiopia. 16

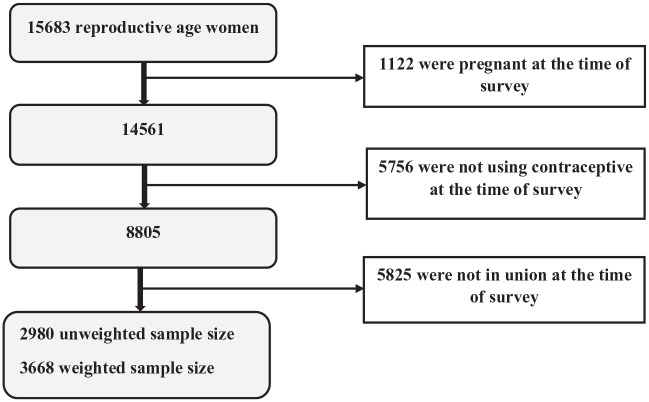

A stratified two-stage cluster sampling technique was applied using the 2007 Population and Housing Census as a sampling frame. In the first stage, 645 enumeration areas (EAs) were selected with probability proportional to the EA size and with independent selection in each sampling stratum. In the second stage, on average 28 households were systematically selected from each EA. A total weighted sample of 3668 married reproductive age women (15–49 years) currently using contraceptives was included in this study. Those women who were not using contraceptives, un-married or not in a union, and pregnant at the time of the survey were excluded from the analysis. Thus, out of the total 15683 reproductive age women included in the 2016 EDHS, 1122 pregnant women were excluded at an initial step and then 5756 women who were not using contraceptives during the survey were dropped. Finally, women who were not in a union at the time of the survey were excluded which yielded an unweighted sample size of 2980 women. To handle the disproportionate allocation of samples in the EDHS, we applied sampling weight and the final weighted sample size for this study was 3668 (Figure 1). The detailed sampling procedure exists in the full EDHS 2016 report. 16

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the married reproductive age women included in this study using the 2016 EDHS data.

Study variables and operational definitions

Dependent variable

The outcome variable of this study was “married women’s independent decision on contraceptive use.” For the analysis purpose, the outcome variable was dichotomized into “not autonomous = 0” (for married reproductive age women who reported that the decision on their contraceptive use was made mainly by her husband/partner, respondent and her husband/partner, and others) and “autonomous = 1” (for married reproductive age women who reported that the decision on their contraceptive use was made only by themselves).3,29

Independent variables

Independent variables were classified into individual-level variables and community-level variables. Individual-level variables were respondent’s age, couple’s age difference, type of marriage, birth order, respondent’s education, respondent’s occupation husband’s education, husband’s occupation, wealth index, religion, exposure to mass media, birth order, age at marriage, number of living children, birth interval, a desired number of children, knowledge of modern method, visiting health facility in the last 12 months, intimate partner violence, and discussing family planning with a health worker. Community-level variables were region, residence, distance to the health facility, community exposure to family planning message, and proportion of women working in the community.

“Region” was grouped into three categories (small peripheral, larger central, or metropolitan) based on their geopolitical features.41,42 “Small peripheral” include Afar, Somali, Benishangul, and Gambella regions. The “larger central” regions include Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, and SNNPRs, while “Metropolitan” include Harari region, Dire-Dawa, and Addis Ababa administrative cites.

“Community exposure to family planning message” and “proportion of women working in the community” were aggregated from individual information and then the aggregated values were categorized as “low” if the median value or proportion of the clusters were below the national level and “high” if the median values of the clusters were above the national level. 43

“Exposure to mass to mass media” was generated from the variables (watching television (TV), listening to the radio, and reading newspapers). Thus, women who watch TV or listened to radio or read a newspaper less than once a week and at least once a week were considered as having exposure to mass media (coded = Yes “1”), while those who did not watch TV or listen to the radio or read a newspaper at all were categorized as not having exposure to mass media (coded = No “0”).44,45

“Couple age difference” was obtained by subtracting woman’s age from her husband’s age (age of husband − age of a woman) and further categorized as “negative” (age of a woman is greater than that of husband), “equal” (age of woman and husband is equal), “less than 10 years” (husband is less than 10 years older than women), and “equal or greater than 10 years” (husband’s age exceeds women’s age by 10 years and above). 46

“Birth order” is the number of birth/s the woman had in her life until this survey was conducted. Accordingly, women who gave birth once were recoded as “first birth order,” twice as “second birth order,” and those who gave birth three times and more as “third birth order and above.”

“Birth interval” (the time interval between successive two births that was recorded in months in the EDHS 2016 data set) was categorized as “<24 months” for women with the time gap between two successive births of less than 24 months, and “⩾24 months” for women with an interval of 24 months and above. 45

Data management and statistical analysis

In the EDHS, sample allocation to different regions as well as urban and rural areas was not proportional. Thus, sample weights to the data were applied to estimate proportions and frequencies to adjust disproportionate sampling and non-response. A full clarification of the weighting procedure was explained in the 2016 EDHS report. 16 The analysis was done using Stata version 16.0. The presence of multicollinearity among predictors was checked through variance inflation factor (VIF) taking the cut-off value of 10. Predictors having a VIF value of less than 10 were considered responses as the non-appearance of multicollinearity.

Bivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis

The effect of each predictor on the outcome variable was checked at a p-value of 0.25. All predictors with a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis were considered as candidates for multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis.47,48

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis

To account for the clustering effects (i.e. women are nested within clusters) of 2016 EDHS data, a multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the effects of each predictor of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use.

Model building and comparison

We have fitted four models that contain predictors of interest for this study. Model I (null model), a model without independent variables to test random variability in the intercept and to estimate the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) and proportion change in variance (PCV). Model II, a model with only community-level explanatory variables. Model III, a model with only individual-level explanatory variables, and Model IV (full model), a model with both individual- and community-level predictors simultaneously. The fitted model was

where πij is the probability of women who had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use, 1 − πij is the probability of not having decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among married women, β0 is the log odds of the intercept, β1 . . . βn is the amount of effect by the individual- and community-level variables, Χ1 . . . Χn is the independent variables at the individual and community level, uoj is the random error at community (cluster), and eij is the random error at the individual level.

ICC was calculated as the proportion of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use between cluster variations in the total variation

where Var(uoj) is the community (cluster) level variance and the assumed household variance component, which is Π2/3 = 3.29.

The variability on the odds of married women decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use explained by successive models was calculated by PCV as

where Ve is the variance in married women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use in the null model (Model I), and Vmi is the variances in the successive model (Model IV or full model).

Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) value was used for model selection criteria and the model with a low AIC value was considered as a best-fitted model for this analysis. From the models fitted, Model IV (full model), a model with both individual- and community-level predictors has the smallest AIC value. Hence, Model IV (full model) best fits the data. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) in the multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis was used to select variables that have a statistically significant effect on women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use.

Ethical consideration

The data were accessed from the DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com) after getting registered and permission was got (AuthLetter_147887). The retrieved data were used for this registered research only. The data were treated as confidential and no determination was made to identify any household or individual respondent.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Out of the total respondents, 76.5% of women resided in rural settings, 53.1% did not attend formal education, 51.2% were Orthodox religion followers, and 47.7% of the respondent’s age range from 25 to 34 years. About 62% of the respondent were married at the age of 18 years above, 54.2% did not have exposure to mass media, and 47% were non-working. Concerning partner’s characteristics, partners of 39% and 58% of women had no formal schooling and were engaged in agriculture as their main occupation. It was also found that 65.8% of women gave birth to at least three children, 83% had a birth interval of 24 months and above, and 75.4% of them were less than 10 years younger than their partner (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants, Ethiopia, 2016.

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Urban | 862 | 23.5 |

| Rural | 2806 | 76.5 | |

| Region | Small peripheral | 59 | 1.6 |

| Large central | 3388 | 92.4 | |

| Metropolitan | 221 | 6.0 | |

| Distance to the health facility | Big problem | 1674 | 45.6 |

| Not a big problem | 1994 | 54.4 | |

| Community exposure to FP message | Low exposure | 2331 | 63.6 |

| High exposure | 1337 | 36.4 | |

| Proportion of women working in the community | Low | 1889 | 51.8 |

| High | 1769 | 48.2 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 1877 | 51.2 |

| Protestant | 968 | 26.4 | |

| Muslim | 768 | 20.9 | |

| Others+ | 55 | 1.5 | |

| Current age | 15–24 years | 850 | 23.2 |

| 25–34 years | 1750 | 47.7 | |

| 35–49 years | 1068 | 29.1 | |

| Women’s age at first marriage | <18 years | 1397 | 38.1 |

| >18 years | 2271 | 61.9 | |

| Women’s educational status | No education | 1948 | 53.1 |

| Primary | 1146 | 31.3 | |

| Secondary | 343 | 9.3 | |

| Higher | 231 | 6.3 | |

| Husband’s educational status | No education | 1427 | 38.9 |

| Primary | 1445 | 39.4 | |

| Secondary | 432 | 11.8 | |

| Higher | 364 | 9.9 | |

| Women’s occupation | No work | 1729 | 47.1 |

| Professional | 249 | 6.8 | |

| Business | 703 | 19.2 | |

| Agriculture | 872 | 23.8 | |

| Others++ | 115 | 3.1 | |

| Husband’s occupation | No work | 330 | 9.0 |

| Professional | 319 | 8.7 | |

| Business | 635 | 17.3 | |

| Agriculture | 2138 | 58.3 | |

| Others++ | 246 | 6.7 | |

| Wealth index | Poorest | 382 | 10.4 |

| Poorer | 645 | 17.6 | |

| Middle | 765 | 20.9 | |

| Richer | 818 | 22.3 | |

| Richest | 1058 | 28.8 | |

| Media exposure | No | 1988 | 54.2 |

| Yes | 1680 | 45.8 | |

| Birth order | First | 640 | 17.4 |

| Second | 615 | 16.8 | |

| Third and above | 2413 | 65.8 | |

| Number of living children | ⩽2 | 1635 | 44.6 |

| >2 | 2033 | 55.4 | |

| Birth interval | <24 months | 470 | 17.0 |

| ⩾24 months | 2289 | 83.0 | |

| Type of marriage | Monogamy | 3497 | 95.3 |

| Polygamy | 171 | 4.7 | |

| Couple’s age difference | Negative | 119 | 3.2 |

| Equal | 79 | 2.2 | |

| <10 years | 2767 | 75.4 | |

| ⩾10 years | 703 | 19.2 | |

| Desired number of children | 0–2 | 529 | 14.4 |

| 3–4 | 1642 | 44.8 | |

| 5+ | 1146 | 31.3 | |

| God/Allah’s will | 265 | 7.2 | |

| Do not know | 86 | 2.4 | |

| Knowledge of modern method | No | 245 | 6.7 |

| Yes | 3423 | 93.3 | |

| Visited health facility in the last 12 months | No | 1608 | 43.8 |

| Yes | 2060 | 56.2 | |

| Intimate partner violence | No | 1262 | 76.9 |

| Yes | 379 | 23.1 | |

| Discussed FP with health worker | No | 479 | 37.6 |

| Yes | 793 | 62.4 |

FP: family planning.

Unweighted sample size for all variable included in the analysis is 2980, except for intimate partner violence (n = 1287), discussed FP with health worker (n = 1023).

Others+: catholic, traditional, and other EDHS category.

Others++: other EDHS category.

Women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use

Overall, 793 (21.6% (95% CI = 20.1%–22.9%)) women had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use.

Univariable analysis

The result of the chi-square test showed that place of residence, region, community exposure to family planning message, religion, women’s age, age at marriage, women’s occupation, husband’s occupation, wealth index, exposure to mass media, the desired number of children, and experiencing intimate partner violence were significantly associated with women decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable investigation (chi-square test) of the association between individual- and community-related variables and married women decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use in Ethiopia, 2016.

| Variables | Women’s decision-making autonomy | Chi-square (χ2) test result | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous | Non-autonomous | |||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 197 (24.9) | 665 (23.1) | 19.5 | <0.01* |

| Rural | 595 (75.1) | 2211 (79.9) | ||

| Region | ||||

| Small peripheral | 11 (1.4) | 48 (1.7) | 29.2 | <0.01* |

| Large central | 723 (91.2) | 2666 (92.7) | ||

| Metropolitan | 58 (7.4) | 162 (5.6) | ||

| Distance to health facility | ||||

| Big problem | 350 (44.2) | 1324 (46.0) | 0.5 | 0.47 |

| Not a big problem | 442 (55.8) | 1552 (54.0) | ||

| Community exposure to FP message | ||||

| Low exposure | 505 (63.7) | 1827 (63.5) | 9.1 | <0.01* |

| High exposure | 287 (36.3) | 1049 (36.5) | ||

| Proportion of women working in the community | ||||

| Low | 422 (53.3) | 1477 (51.4) | 0.4 | 0.52 |

| High | 370 (46.7) | 1398 (48.6) | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Orthodox | 445 (56.1) | 1432 (49.8) | 12.4 | <0.01* |

| Protestant | 180 (22.7) | 788 (27.4) | ||

| Muslim | 163 (20.5) | 606 (21.1) | ||

| Others+ | 5 (0.7) | 50 (1.7) | ||

| Current age | ||||

| 15–24 years | 163 (20.6) | 687 (23.9) | 10.1 | <0.01* |

| 25–34 years | 344 (43.4) | 1406 (48.9) | ||

| 35–49 years | 285 (36.0) | 783 (27.2) | ||

| Women’s age at first marriage | ||||

| ⩾18 years | 493 (62.2) | 1778 (61.8) | 13.6 | <0.01* |

| <18 years | 299 (37.8) | 1098 (38.2) | ||

| Women’s educational status | ||||

| No education | 471 (59.4) | 1477 (51.3) | 1.5 | 0.68 |

| Primary | 221 (27.8) | 926 (32.2) | ||

| Secondary | 62 (7.8) | 281 (9.8) | ||

| Higher | 39 (5.0) | 192 (6.7) | ||

| Husband’s educational status | ||||

| No education | 356 (44.9) | 1072 (37.3) | 7.2 | 0.07* |

| Primary | 283 (35.8) | 1162 (40.4) | ||

| Secondary | 91 (11.4) | 341 (11.8) | ||

| Higher | 63 (7.9) | 301 (10.5) | ||

| Women’s occupation | ||||

| No work | 388 (48.9) | 1342 (46.7) | 14.8 | <0.01* |

| Professional | 54 (6.8) | 195 (6.8) | ||

| Business | 158 (20.0) | 544 (18.9) | ||

| Agriculture | 166 (20.9) | 707 (24.6) | ||

| Others++ | 27 (3.4) | 88 (3.0) | ||

| Husband’s occupation | ||||

| No work | 80 (10.1) | 250 (8.7) | 9.8 | 0.04* |

| Professional | 57 (7.2) | 262 (9.1) | ||

| Business | 138 (17.5) | 497 (17.3) | ||

| Agriculture | 450 (56.9) | 1687 (58.7) | ||

| Others++ | 6 (8.4) | 179 (6.2) | ||

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest | 104 (13.1) | 279 (9.7) | 26.0 | <0.01* |

| Poorer | 168 (21.1) | 478 (16.6) | ||

| Middle | 178 (19.9) | 607 (21.1) | ||

| Richer | 132 (16.7) | 686 (23.9) | ||

| Richest | 231 (29.2) | 827 (28.7) | ||

| Media exposure | ||||

| No | 453 (57.2) | 1535 (53.4) | 11.7 | <0.01* |

| Yes | 339 (42.8) | 1341 (46.6) | ||

| Birth order | ||||

| First | 118 (14.8) | 523 (18.2) | 3.8 | 0.15 |

| Second | 127 (16.0) | 488 (17.0) | ||

| Third and above | 548 (69.2) | 1865 (64.8) | ||

| Number of living children | ||||

| <2 | 335 (42.3) | 1300 (45.2) | 0.3 | 0.59 |

| >2 | 457 (57.7) | 1576 (54.8) | ||

| Birth interval | ||||

| <24 months | 78 (13.0) | 392 (18.2) | 2.75 | 0.09 |

| ⩾24 months | 582 (83.0) | 1761 (81.8) | ||

| Desired number of children | ||||

| 0–2 | 108 (13.6) | 421 (14.6) | 15.0 | <0.01* |

| 3–4 | 314 (39.6) | 1329 (46.2) | ||

| 5+ | 276 (34.8) | 87 (30.3) | ||

| God/Allah’s will | 64 (8.1) | 200 (7.0) | ||

| Do not know | 31 (3.9) | 56 (1.9) | ||

| Knowledge of modern method | ||||

| No | 58 (7.2) | 188 (6.6) | 0.2 | 0.69 |

| Yes | 736 (92.8) | 2688 (93.5) | ||

| Visited health facility in the last 12 months | ||||

| No | 347 (43.8) | 1261 (43.8) | 0.4 | 0.88 |

| Yes | 445 (56.2) | 1615 (56.2) | ||

FP: family planning.

Others+: catholic, traditional, and other EDHS category.

Others++: other EDHS category.

Empty multilevel logistic regression model (null model)

From the null model, the variance of the random factor was 0.89. This variance estimate is greater than zero, which indicates that there are cluster area differences in women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use in Ethiopia, and thus, multilevel logistic regression model should be considered for further analysis.

The intra-cluster correlation coefficient indicated that 21% of the total variability in women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use is due to differences across cluster areas, with the remaining unexplained 79% attributable to individual differences. According to the PCV value, 53% of the variation in women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use across communities was described by predictors (both individual- and community-related) included in the full model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Community-level variance of two-level mixed-effect logit models predicting women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use in Ethiopia, 2016.

| Random effect | Null model | Full model |

|---|---|---|

| Community-level variance | 0.89 | 0.42 |

| ICC (%) | 21 | 11 |

| PCV (%) | Reference | 53 |

| Model fitness statistics (AIC) | 3654 | 2644 |

| Median odds ratio (MOR) | 2.43 | 1.68 |

ICC: intra-class correlation coefficient; PCV: proportion change in variance; AIC: Akaike’s information criterion.

Multilevel logistic regression model (full model)

In the multivariable multilevel logistic regression model, residence site, women’s educational status, religion, age, age at marriage, wealth index, and exposure to mass media were statistically associated with women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. After adjusting for covariates, the odds of the women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among women who were residing in rural settings were lower than those who were living in an urban area (AOR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.23–0.87). However, women who lived in a community with high exposure to family planning messages were twice more likely to make an independent decision on contraceptive use compared to those in a community with low exposure to family planning messages (AOR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.67–3.05), respectively.

Women who had their first marriage before the age of 18 years were less likely to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to women who married at 18 years or above (AOR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.12–0.92). Similarly, the likelihood of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among women in the age range of 35–49 years (AOR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.36–4.69) was more than two times higher compared to their reference group.

In this study, the odds of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among Muslims were lower compared to those whose religion was orthodox (AOR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.29–0.95). Similarly, women from the richer households were more likely to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to those women from the poorest households (AOR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.32–3.11). Besides, women who had exposure to mass media (AOR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.52–3.23) and those who visited a health facility in the last 12 months (AOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.34–3.87) had a higher likelihood to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression of the individual- and community-related variables associated with women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use, Ethiopia, 2016.

| Variables | Unadjusted analysis, COR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis, AOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II | Model III | Model IV | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| Rural | 0.76 (0.47–0.98) | 0.50 (0.27–0.91) | 0.48 (0.23–0.87)* | |

| Region | ||||

| Small peripheral | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| Large central | 1.19 (0.82–1.74) | 1.26 (0.86–1.85) | 1.26 (0.74–2.15) | |

| Metropolitan | 1.70 (1.11–2.61) | 1.53 (0.95–2.46) | 1.65 (0.83–2.31) | |

| Distance to the health facility | ||||

| Big problem | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| Not a big problem | 1.06 (0.77–1.46) | 1.01 (0.72–1.43) | 1.01 (0.65–1.53) | |

| Community exposure to FP message | ||||

| Low exposure | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| High exposure | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) | 2.25 (1.71–3.11) | 2.22 (1.67–3.05)* | |

| Proportion of women working in the community | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| High | 1.06 (0.79–1.40) | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) | 1.08 (0.70–1.69) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Orthodox | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Protestant | 0.59 (0.39–1.09) | 0.49 (0.28–1.03) | 0.68 (0.55–1.11) | |

| Muslim | 0.91 (0.59–1.39) | 0.94 (0.54–1.65) | 0.53 (0.29–0.95)* | |

| Others+ | 0.25 (0.09–0.76) | 0.30 (0.09–1.03) | 0.36 (0.10–1.20) | |

| Current age | ||||

| 15–24 years | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 years | 1.19 (0.85–1.68) | 1.50 (0.71–3.31) | 1.28 (0.93–1.91) | |

| 35–49 years | 1.78 (1.21–2.64) | 2.23 (1.02–4.98) | 2.09 (1.36–4.69)* | |

| Women’s age at first marriage | ||||

| ⩾18 years | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| <18 years | 1.04 (0.78–0.1.37) | 0.41 (0.19–0.96) | 0.33 (0.12–0.92)* | |

| Women’s educational status | ||||

| No education | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.69 (0.50–0.95) | 0.71 (0.45–1.10) | 0.68 (0.43–1.06) | |

| Secondary | 0.62 (0.39–0.96) | 0.47 (0.22–1.04) | 0.39 (0.14–1.01) | |

| Higher | 0.54 (0.29–1.02) | 0.32 (0.11–1.19) | 0.25 (0.12–1.07) | |

| Husband’s educational status | ||||

| No education | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.72 (0.52–0.98) | 0.85 (0.57–1.28) | 0.86 (0.58–1.30) | |

| Secondary | 0.79 (0.52–1.20) | 1.07 (0.51–2.23) | 1.05 (0.50–2.20) | |

| Higher | 0.59 (0.34–1.01) | 1.12 (0.44–2.87) | 1.11 (0.43–2.88) | |

| Women’s occupation | ||||

| No work | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Professional | 1.10 (0.58–2.10) | 2.71 (1.01–10.34) | 2.64 (0.99–10.29) | |

| Business | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 1.22 (0.75–1.98) | 1.21 (0.74–1.98) | |

| Agriculture | 0.80 (0.56–1.13) | 0.56 (0.35–1.05) | 0.57 (0.35–1.01) | |

| Others++ | 1.22 (0.64–2.31) | 0.84 (0.31–2.29) | 0.78 (0.28–2.19) | |

| Husband’s occupation | ||||

| No work | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Professional | 0.67 (0.36–1.26) | 0.64 (0.28–1.43) | 0.63 (0.28–1.39) | |

| Business | 0.80 (0.49–1.31) | 0.97 (0.50–1.88) | 0.93 (0.48–1.79) | |

| Agriculture | 0.83 (0.54–1.28) | 0.77 (0.45–1.32) | 0.79 (0.46–1.36) | |

| Others++ | 1.16 (0.62–2.15) | 1.48 (0.63–3.47) | 1.35 (0.56–3.22) | |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Poorer | 1.10 (0.70–1.69) | 1.19 (0.47–2.07) | 1.19 (0.65–2.16) | |

| Middle | 0.70 (0.42–118) | 0.76 (0.38–1.51) | 0.76 (0.38–1.52) | |

| Richer | 0.55 (0.34–0.91) | 1.72 (2.88–5.41) | 1.67 (1.32–3.11)* | |

| Richest | 0.85 (0.55_1.32) | 1.07 (0.56–2.07) | 0.85 (0.41–1.76) | |

| Media exposure | ||||

| No | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.82 (0.62–1.10) | 2.29 (1.61–3.84) | 2.13 (1.52–3.23)* | |

| Birth order | ||||

| First | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Second | 1.15 (0.70–1.88) | 1.01 (0.49–2.71) | 1.09 (0.45–2.68) | |

| Third and above | 1.39 (0.91–2.12) | 1.28 (0.03–2.28) | 1.31 (0.68–3.12) | |

| Number of living children | ||||

| <2 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| >2 | 1.25 (0.95–1.65) | 0.97 (0.45–2.11) | 0.97 (0.44–2.68) | |

| Birth interval | ||||

| <24 months | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ⩾24 months | 1.46 (0.88–2.42) | 1.47 (0.88–2.46) | 1.46 (0.87–2.45) | |

| Desired number of children | ||||

| 0–2 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3–4 | 1.03 (0.67–1.60) | 0.85 (0.48–1.54) | 0.86 (0.48–1.55) | |

| 5+ | 1.33 (0.87–2.01) | 1.11 (0.63–1.95) | 1.14 (0.65–2.02) | |

| God/Allah’s will | 1.46 (0.81–2.65) | 1.13 (0.53–2.45) | 1.15 (0.54–2.45) | |

| Do not know | 2.14 (1.06–4.35) | 2.71 (1.05–6.99) | 2.82 (1.08–5.03) | |

| Knowledge of modern method | ||||

| No | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.85 (0.50–1.45) | 0.59 (0.30–1.15) | 0.58 (0.30–1.11) | |

| Visited health facility in the last 12 months | ||||

| No | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.29 (0.89–1.94) | 2.11 (1.44–3.99) | 2.01 (1.34–3.87)* | |

FP: family planning; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; COR: crude odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Others+: catholic, traditional, and other EDHS category.

Others++: other EDHS category.

Statistically significant variables at 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use is an essential component of SRH rights. 49 This study assessed the level of women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use and its associated factors in Ethiopia using the 2016 DHS data set. It was revealed that only 21.6% of women in Ethiopia had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. This finding is in line with the previous studies in Mahikeng, South Africa 14 and Ethiopia.27,28

However, our finding is lower compared to the results of the studies in Adwa, North Ethiopia, 29 Dinsho, Southeast Ethiopia, 30 rural districts of Southern Ethiopia, 13 South Africa, 26 and Nigeria 17 which reported that 36%, 52%, 58%, 41%, and 24% of women respectively had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Moreover, the proportion of women who had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use in this study is substantially lower than the findings reported from the studies in Mizan-Aman 67%, 32 Basoliben 80%, 31 and Northwest Ethiopia 77%. 50 On the contrary, our finding is higher than a study in Senegal, 3 which found that 6% of women had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. The discrepancy might be due to the methodological differences of the studies and variations in the socio-cultural and religious context of the study areas.

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression model identified the place of residence and community exposure to family planning message (at community level), religion, wealth index, exposure to mass media, current age, age at marriage, and visiting health facility (at individual level) as the factors affecting women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Accordingly, women from rural dwellings had a lower likelihood of having decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to those residing in urban settings. This finding is consistent with the result of the previous studies in Ethiopia,33,35 which found higher decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among urban women. This might be because women in urban residences have better educational opportunities and have access to information, particularly on contraceptives and other SRH-related issues than their rural counter group, which enables them to have greater involvement in the household decision-making process and to decide on contraceptive use.

Married women in a community with high exposure to family planning messages were nearly twice more likely to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to their counter group. This finding is in line with the result of a study done in Ethiopia. 27 Furthermore, it is supported by the finding of a study in Pakistan that reported a positive relationship between women’s decision-making autonomy and their awareness about family planning. 51 The possible explanation for this finding is women exposed to family planning information might have better understanding of reproductive health rights and the advantages of contraceptives that encourages their participation in reproductive health decisions.

The analysis also identified religion as the individual-level factor that significantly influenced women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. For instance, women who were Muslim were less likely to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use than Orthodox religious followers. This finding is nearly in agreement with the result of a study in South Africa 14 and Ghana, 52 which found higher odds of decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among Christian religion fellows. Socio-cultural barriers and religious articulation of behavioral norms with a bearing on fertility behavior accompanied by gender inequality might contribute to these phenomena.

The odds of decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among women aged 35–49 years were 2.09 times higher compared to those women from the age of 15–24 years. This finding is similar to the previous studies in Ethiopia,3,13,33 which reported higher decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use as the age of respondents increased. This result can be explained by the fact that younger women are less likely to visit family planning clinics and lack awareness due to limited access to SRH information, 53 and therefore have little control over their contraceptive decision. On the contrary, our finding is inconsistent with the result of the studies in Southern Ethiopia,30,32 where higher decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use was reported among younger women. Methodological differences might contribute to these variations. For instance, the previous two studies used a simple random sampling method to reach the study population.

Women who had their first marriage before the age of 18 years were less likely to have decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to those married at 18 years or above. This finding is consistent with a previous study, 25 which reported a lower likelihood of decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among women who married at an early age. This might be due to the inferior negotiating power of younger women associated with limited educational opportunities as a consequence of early marriage.54,55

Exposure to the sources of contraceptive knowledge enables women to have information about fertility control methods and thus freely make the decision to use these services on informed choice. Accordingly, this study showed that decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use among women who read newspapers or magazines and/or listened to radio and/or television increased by more than twofold compared to their reference group, which is supported by the existence of the positive relationship between use of contraceptive methods and exposure to mass media. 56 Furthermore, consistent with the results of previous studies,25,57 this study revealed that women from richer households had increased odds of having decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use compared to those from the poorest households. It was also found that women who visited a health facility in the last 12 months were nearly twice more likely to make an independent decision on contraceptive use. This might be because women who visit health facilities have better access to health information and understanding of health issues, and thus more likely to make health decisions autonomously.

Strengths and limitations

This study used nationally representative data and applied an advanced model, a mixed-effect model, to handle the clustering effect. However, the cross-sectional nature of the EDHS data used in this study which relies on the self-reported responses of the events that occurred in the past may be influenced by recall bias. Besides, information about women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use was collected based on self-reporting, which is likely to be subjected to social desirability bias due to its socio-cultural nature.

Study implication and recommendation for future study

The finding of this study implies that the majority of married reproductive age women in Ethiopia are non-autonomous on the decision regarding contraceptive use and different socio-demographic and health-related factors were identified to have a significant influence on women’s independent decision to use contraceptives. Therefore, qualitative studies that explore individual-, household-, and community-level barriers hindering women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use are needed to scale-up contraceptive use at national and local levels.

Conclusion

This study revealed that less than one-fourth of married women of reproductive age (15–49 years) had decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use, which is significantly lower than the figures reported in the previous studies. The mixed-effect logistic regression analysis showed that place of residence, community exposure to family planning message, women’s current age, age at first marriage, religion, exposure to mass media, household wealth index, and visiting health facility were identified as the factors affecting women’s decision-making autonomy on contraceptive use. Therefore, the government should promote women’s autonomy on contraceptive use as an essential component of SRH rights through mass media, with particular attention for adolescent women, women living in the poorest households, and those residing in rural settings of the country. Moreover, short-term training about SRH rights should be offered to religious leaders as a strategy to disseminate health messages. The existing health extension program should be supported on the dissemination of family planning messages in the areas with limited access to mass media to reach rural adolescent women. Improving the health-seeking behavior of the community and sexual and reproductive health education targeting school adolescents are also crucial in the realization of sexual and reproductive health rights.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the ICF international for granting access to use the 2016 EDHS data set for this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions: K.U.M., S.B.A., and A.W.T. had substantial contributions to the conception and design of this research, involved in the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the article. M.A. designed the study and revised the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The data were accessed from the DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com) after getting registered and permission was obtained (AuthLetter_147887). The accessed data were used for the registered research only. The data were treated as confidential and no effort was made to identify any household or individual respondent.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legally authorized representatives before the study initiation.

ORCID iD: Kusse Urmale Mare  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8522-1504

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8522-1504

Availability of data and materials: The raw data set used and analyzed in this study can be accessed from the DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com).

References

- 1. Mistry R, Galal O, Lu M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: a contextual analysis. Soc Sci Med 2009; 69(6): 926–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Acharya DR, Bell JS, Simkhada P, et al. Women’s autonomy in household decision-making: a demographic study in Nepal. Reprod Health 2010; 7(1): 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sougou NM, Bassoum O, Faye A, et al. Women’s autonomy in health decision-making and its effect on access to family planning services in Senegal in 2017: a propensity score analysis. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. OlaOlorun FM, Hindin MJ. Having a say matters: influence of decision-making power on contraceptive use among Nigerian women ages 35–49 years. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(6): e98702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Viswan SP, Ravindran TKS, Kandala NB, et al. Sexual autonomy and contraceptive use among women in Nigeria: findings from the demographic and health survey data. Int J Womens Health 2017; 9: 581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wado YD. Women’s autonomy and reproductive healthcare-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Fairfax, VA: ICF International, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loll D, Fleming PJ, Manu A, et al. Reproductive autonomy and modern contraceptive use at last sex among young women in Ghana. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2019; 45: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zeleke LB, Alemu AA, Kassahun EA, et al. Individual and community level factors associated with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Ethiopia. Sci Rep 2021; 11(1): 12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rahman M. Women’s autonomy and unintended pregnancy among currently pregnant women in Bangladesh. Matern Child Health J 2012; 16(6): 1206–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Biswas AK, Shovo TEA, Aich M, et al. Women’s autonomy and control to exercise reproductive rights: a sociological study from rural Bangladesh. SAGE Open 2017; 7(2): 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kulczycki A. Husband-wife agreement, power relations and contraceptive use. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2008; 34(3): 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Orr MG, et al. Toward a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: evidence from the United States. Stud Fam Plan 2009; 40(2): 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alemayehu M, Meskele M. Health care decision making autonomy of women from rural districts of Southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health 2017; 9: 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Osuafor GN, Maputle SM, Ayiga N. Factors related to married or cohabiting women’s decision to use modern contraceptive methods in Mahikeng, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2018; 10(1): e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Nations. World family planning: 2017 highlights, 2017, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/WFP2017_Highlights.pdf

- 16. Central Statistical Agency. The 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey preliminary report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alabi O, Odimegwu CO, De-Wet N, et al. Does female autonomy affect contraceptive use among women in northern Nigeria? Afr J Reprod Health 2019; 23(2): 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. AlSumri HH. A national study: the effect of Egyptian married women’s decision-making autonomy on the use of modern family planning methods. Afr J Reprod Health 2015; 19(4): 68–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Acharya D, Adhikari R, Ranabhat C. Factors associated with non-use of contraceptives among married women in Nepal. J Health Promot 2019; 7: 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tadesse M, Teklie H, Yazew G, et al. Women’s empowerment as a determinant of contraceptive use in Ethiopia further analysis of the 2011 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. DHS Fur Anal Rep 2013; 82: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al Riyami A, Afifi M, Mabry RM. Women’s autonomy, education and employment in Oman and their influence on contraceptive use. Reprod Health Matter 2004; 12(23): 144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Atiglo DY, Codjoe SNA. Meeting women’s demand for contraceptives in Ghana: does autonomy matter? Women Health 2019; 59(4): 347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahman MM, Mostofa MG, Hoque MA. Women’s household decision-making autonomy and contraceptive behavior among Bangladeshi women. Sex Reprod Healthc 2014; 5(1): 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters JS, Wolper A. Women’s rights, human rights: international feminist perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. UNFPA. Tracking women’s decision-making for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights, 2020, https://www.unfpa.org/resources/tracking-womens-decision-making-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-reproductive-rights

- 26. National Department of Health and ICF. South Africa demographic and health survey 2016. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; Lexington, KY: ICF, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Delbiso TD. Gender power relations in reproductive decision-making: the case of Gamo migrants in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Afr Popul Stud 2013; 27(2): 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eshete A, Adissu Y. Women’s joint decision on contraceptive use in Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia: a community based comparative cross-sectional study. Int J Fam Med 2017; 2017: 9389072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alemayehu M, Hailesellasie K, Biruh G, et al. Married women’s autonomy and associated factors on modern contraceptive use in Adwa town, northern Ethiopia. Science 2014; 2(4): 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dadi D, Bogale D, Minda Z, et al. Decision-making power of married women on family planning use and associated factors in Dinsho Woreda, south east Ethiopia. Open Access J Contracept 2020; 11: 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alemayehu B, Kassa GM, Teka Y, et al. Married women’s decision-making power in family planning use and its determinants in Basoliben, northwest Ethiopia. Open Access J Contracept 2020; 11: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Belay AD, Mengesha ZB, Woldegebriel MK, et al. Married women’s decision making power on family planning use and associated factors in Mizan-Aman, south Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2016; 16(1): 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edossa ZK, Debela TF, Mizana BA. Women’s decision on contraceptive use in Ethiopia: multinomial analysis of evidence from Ethiopian demographic and health survey. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol 2020; 7: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Osamor PE, Grady C. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: a synthesis of the literature. Int J Womens Health 2016; 8: 191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bogale B, Wondafrash M, Tilahun T, et al. Married women’s decision making power on modern contraceptive use in urban and rural southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2011; 11(1): 342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. UNFPA. Sexual and reproductive health for all: reducing poverty, advancing development and protecting human rights, 2010, https://www.unfpa.org/fr/node/6149

- 37. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. National reproductive health strategy 2006–2015, https://www.exemplars.health/-/media/resources/underfive-mortality/ethiopia/ethiopia-fmoh_national-reproductive-health-strategy.pdf?la=en. 2006

- 38. Constitution of Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Proclamation No. 1/1995 Proclamation of the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1995, https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkozje))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2665274

- 39. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Ethiopia health sector transformational plan (2015/16–2019/20), 2015, https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/ethiopia-health-sector-transformation-plan-201516-201920

- 40. Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018; 391(10140): 2642–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abrha S, Shiferaw S, Ahmed KY. Overweight and obesity and its socio-demographic correlates among urban Ethiopian women: evidence from the 2011 EDHS. BMC Public Health 2016; 16(1): 636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahmed KY, Page A, Arora A, et al. Trends and determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2016. Int Breastfeed J 2019; 14: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tegegne TK, Chojenta C, Forder PM, et al. Spatial variations and associated factors of modern contraceptive use in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis. BMJ Open 2020; 10(10): e037532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tadesse AW, Aychiluhm SB, Mare KU. Individual and community-level determinants of iron-folic acid intake for the recommended period among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. Heliyon 2021; 7(7): e07521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aychiluhm SB, Tadesse AW, Mare KU, et al. A multilevel analysis of short birth interval and its determinants among reproductive age women in developing regions of Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(8): e0237602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kitila SB, Terfa YB, Akuma AO, et al. Spousal age difference and its effect on contraceptive use among sexually active couples in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Contracept Reprod Med 2020; 5(1): 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, et al. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Sour Code Biol Med 2008; 3(1): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression, vol. 398. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49. UNFPA. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: the cornerstone of sustainable development, 2018, https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights-cornerstone-sustainable-development

- 50. Tadesse SY, Emiru AA, Tafere TE, et al. Women’s autonomy decision making power on postpartum modern contraceptive use and associated factors in north west Ethiopia. Adv Public Health 2019; 2019: 1861570. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nadeem M, Malik MI, Anwar M, et al. Women decision making autonomy as a facilitating factor for contraceptive use for family planning in Pakistan. Soc Indicat Res 2021; 156(1): 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Crissman HP, Adanu RM, Harlow SD. Women’s sexual empowerment and contraceptive use in Ghana. Stud Fam Plan 2012; 43(3): 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rios-Zertuche D, Blanco LC, Zúñiga-Brenes P, et al. Contraceptive knowledge and use among women living in the poorest areas of five Mesoamerican countries. Contraception 2017; 95(6): 549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mim SA. Effects of child marriage on girls’ education and empowerment. J Educ Learn 2017; 11(1): 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guilbert N. Early marriage, women empowerment and child mortality: married too young to be a “good mother,” 2013, https://basepub.dauphine.psl.eu//bitstream/handle/123456789/11404/DT%202013–05%20Guilbert.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 56. Wado YD. Women’s autonomy and reproductive health-care-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Women Health 2018; 58(7): 729–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. UNFPA. Research on factors that determine women’s ability to make decisions about sexual and reproductive health and rights, 2019, https://www.unfpa.org/resources/research-factors-determine-womens-ability-make-decisions-about-sexual-and-reproductive