Abstract

Fast and reliable identification of microbial isolates is a fundamental goal of clinical microbiology. However, in the case of some fastidious gram-negative bacterial species, classical phenotype identification based on either metabolic, enzymatic, or serological methods is difficult, time-consuming, and/or inadequate. 16S or 23S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) bacterial sequencing will most often result in accurate speciation of isolates. Therefore, the objective of this study was to find a hypervariable rDNA stretch, flanked by strongly conserved regions, which is suitable for molecular species identification of members of the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae. The inter- and intrageneric relationships were investigated using comparative sequence analysis of PCR-amplified partial 16S and 23S rDNAs from a total of 94 strains. When compared to the type species of the genera Acinetobacter, Moraxella, and Neisseria, an average of 30 polymorphic positions was observed within the partial 16S rDNA investigated (corresponding to Escherichia coli positions 54 to 510) for each species and an average of 11 polymorphic positions was observed within the 202 nucleotides of the 23S rDNA gene (positions 1400 to 1600). Neisseria macacae and Neisseria mucosa subsp. mucosa (ATCC 19696) had identical 16S and 23S rDNA sequences. Species clusters were heterogeneous in both genes in the case of Acinetobacter lwoffii, Moraxella lacunata, and N. mucosa. Neisseria meningitidis isolates failed to cluster only in the 23S rDNA subset. Our data showed that the 16S rDNA region is more suitable than the partial 23S rDNA for the molecular diagnosis of Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae and that a reference database should include more than one strain of each species. All sequence chromatograms and taxonomic and disease-related information are available as part of our ribosomal differentiation of medical microorganisms (RIDOM) web-based service (http://www.ridom.hygiene.uni-wuerzburg.de/). Users can submit a sequence and conduct a similarity search against the RIDOM reference database for microbial identification purposes.

Classification and diagnostic systems for microorganisms have historically been based on the existence of observable characteristics. However, because of limitations in the discriminatory power of these characteristics, problems have arisen in identification and diagnosis (29). A more recent approach for classification and identification of microorganisms involves the comparison of genetic characteristics. These molecular methods are becoming increasingly important in microbiological diagnostics (23). They are an expansion of or an alternative to phenotyping techniques if one or more of the following conditions are met: (i) microorganisms cannot be cultivated or are difficult to cultivate, (ii) organisms grow only slowly and are poorly differentiated, (iii) growth of organisms represents a hazard to laboratory staff, (iv) a suitable test method for phenotyping is not available, and (v) the extent of infection is to be quantitated (e.g., the virus load). Guidelines similar to the phenotypic methods of Koch have already been established for molecular techniques used in the identification of microorganisms involved in particular diseases (9). In most cases, one of the following genomic structures is chosen as target for a molecular diagnosis test: (i) DNA sequences bearing the code for toxic or pathogenic factors, (ii) DNA sequences of specific antigens, (iii) specific DNA plasmid sequences, (iv) DNA sequences bearing rRNA codes, and (v) small sequences, mostly species specific, which are noncoding. The rRNA genes (rDNA) are particularly suitable for identification purposes since they are ubiquitous to all living organisms. They occur as multicopy genes, making their detection relatively easy, and are composed of conserved, variable, and highly variable regions so that probes may be designed to meet a desired level of specificity. Furthermore, they are essential for survival and may be used as a molecular clock for phylogenetic studies (11, 20, 25, 40, 41).

Existing sequence databases and analytical tools (e.g., the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank or Ribosomal Database Project) are not optimal for accurate identification of clinically relevant microorganisms (17). The contents of these databases suffer many drawbacks including the presence of ragged sequence ends, faulty sequence entries (due to error-prone sequencing techniques used earlier), absence of quality control of sequence entries, noncharacterized entries, outdated nomenclature, and lack of type strains pertaining to many clinically important microorganisms. Furthermore, the results are not presented in a user-friendly manner. Our ribosomal differentiation of medical microorganisms (RIDOM) project is a new initiative and attempts to overcome these problems (12).

Culture collection strains of Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae were studied since these families not only contain established human pathogens such as N. meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae but also contain other species which are important as emerging causes of opportunistic infections (19). Molecular identification of these particular isolates should be a good challenge for molecular diagnostic systems in general because these organisms belong to a group of bacteria that is naturally competent and frequently exchanges chromosomal genes. This exchange process could considerably complicate molecular diagnosis and identification. According to Bøvre, the family Neisseriaceae previously consisted of the genera Neisseria, Kingella, Acinetobacter, and Moraxella, the latter genus containing the subgenera Moraxella (rod-shaped bacteria) and Branhamella (cocci) (2, 3). On the basis of DNA hybridization and phylogenetic rDNA sequence analysis results, it is now suggested that Neisseria, Kingella, and Eikenella species are grouped in the family Neisseriaceae in the β subclass of the Proteobacteria. The genera Acinetobacter, Moraxella, and Psychrobacter are removed from the Neisseriaceae and included in the family Moraxellaceae in the γ subclass of the Proteobacteria (26, 27, 32). This classification system is still evolving and therefore not complete.

In practice, a defined and limited sequence run must suffice for the identification process in most cases. To decide the target that best meets the requirements for identification, coherent variable regions of the rRNA operon were studied in a total of 94 Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae strains. The sequence traces and further taxonomic and disease-related information on these strains have also been deposited on our RIDOM web server for prototypic demonstration purposes. The same partial 16S and 23S rDNA sequences were also used to examine the phylogenetic relationships among species of the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae families.

(This study was presented in part at the 99th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Chicago, Ill., 31 May to 3 June 1999.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains investigated in this study are listed in Table 1. Culture collection isolates, including the type strains, were used in this analysis when available. Strains were grown on 5% human blood and chocolate agar plates at 22, 28, or 37°C with 5% CO2. All isolates were identified by conventional biochemical methods (19).

TABLE 1.

Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaccae strains included in the studya

| Species | Strain | EMBL accession number (16S/23S) |

|---|---|---|

| A. baumanni | DSM 30007T, LMG 994 | AJ247197/AF124611; AJ247198/N.D. |

| A. calcoaceticus | DSM 30006T | AJ247199/AF124612 |

| A. haemolyticus | DSM 6962T, LMG 1033 | AJ247200/AF124613; AJ247201/N.D. |

| A. johnsonii | DSM 6963T, LMG 10584 | AJ247202/AF124614; AJ247203/AF242446 |

| A. junii | DSM 6964T, LMG 10577 | AJ247204/AF124615; −/− |

| A. lwoffii | DSM 2403T, LMG 1134, LMG 1138, LMG 1154, LMG 1299, LMG 1300 | AJ247205/AF124616; −/−; AJ247207/AJ242449; AJ247206/AJ242448; N.D./−; AJ247208/− |

| A. radioresistens | DSM 6976T, LMG 10614 | AJ247209/AF124617; AJ247210/AJ242450 |

| Chromobacterium violaceum | DSM 30191T | AJ247211/AF124618 |

| Eikenella corrodens | DSM 8340T, LMG 15557, Oslo 31745/80 | AJ247212/AF124619; −/−; AJ247213/− |

| Iodobacter fluviatilis | DSM 3764T | AJ247214/AF124620 |

| Kingella denitrificans | ATCC 33394T, NCTC 10997 | N.D./AJ228757; AJ247215/AJ242451 |

| K. kingae | DSM 7536T | AJ247216/AF124626 |

| Kingella oralis | ATCC 51147T | AJ247217/AF124627 |

| M. (Branhamella) catharralis | ATCC 25238T, LMG 1133 | AJ247218/AJ228758; AJ247219/AJ242452 |

| Moraxella (B.) caviae | ATCC 14659T, CCUG 355 | AJ247220/AF124637; −/N.D. |

| Moraxella (B.) cuniculi | LMG 8382T, CCUG 27179 | N.D./AJ228759; AJ247221/N.D. |

| Moraxella (B.) ovis | LMG 8381T, ATCC 33078 | AJ247222/AJ228760; −/− |

| Moraxella (Moraxella) atlantae | LMG 5133T, CDC 5118 | N.D./AF124638; N.D./AJ242453 |

| Moraxella (M.) bovis | LMG 986T, LMG 1006 | AJ247223/AF124639; AJ247224/AJ242454 |

| Moraxella (M.) canis | LMG 11194T | AJ247225/AF124640 |

| Moraxella (M.) caprae | NCTC 12877T | N.D./AF124641 |

| M. (M.) equi | LMG 5315T, ATCC 25576 | AJ247226/AF124642; −/N.D. |

| M. (M.) lacunatab | ATCC 11748T, ATCC 17956, ATCC 17967, LMG 1008 | AJ247228/AJ242455; −/AJ242456; AJ247227/AF124643;−/AJ242457 |

| Moraxella (M.) lincolnii | LMG 5127T | AJ247229/AF124644 |

| Moraxella (M.) nonliquefaciens | DSM 6360T, NCTC 7784, LMG 1045 | AJ247230/AF124645; −/−; AJ247231/N.D. |

| Moraxella (M.) osloensis | LMG 5131T, LMG 6916 | AJ247232/AF124646; AJ247233/N.D. |

| N. animalis | NCTC 10212T, ATCC 19573 | AJ247234/AF124628; −/− |

| N. canis | LMG 8383T | AJ247235/AJ228761 |

| Neisseria cinerea | DSM 4630T, LMG 8380 | AJ247236/AJ228762; −/− |

| N. elongata subsp. elongata | LMG 5124T | AJ247252/AJ228763 |

| N. elongata subsp. glycolytica | NCTC 11050T | AJ247253/AF124634 |

| N. elongata subsp. nitroreducens | ATCC 49377T, ATCC 49378 | AJ247254/AF124635; −/− |

| Neisseria flava | Berger 122 | AJ247237/AF124629 |

| Neisseria flavescens | ATCC 13115T, LMG 5297 | N.D./−; N.D./AJ228764 |

| N. gonorrhoeae | DSM 9188T, DSM 9189 Wue 799, Wue 920 | AJ247238/AJ228765; AJ247239/−; −/−; −/− |

| Neisseria iguanae | ATCC 51483T | AJ247240/AF124630 |

| Neisseria lactamica | DSM 4691T, Berger 116 | AJ247241/AJ228766; −/− |

| N. macacae | ATCC 33926T | AJ247243/AF124631 |

| N. meningitidis | DSM 10036T, 2120, 25/634, 264/93, ATCC 13102, ATCC 35559, BZ163, H41/88, H44/76, MC58, Z2491, Z6422 | AJ247244/AJ228767; N.D./−; −/−; −/−; N.D./AJ242458; AJ247245/AJ242459; −/−; N.D./−; N.D./−; −/−; −/−; N.D./− |

| N. mucosa subsp. heidelbergiensis | ATCC 25999T, Berger 114, LMG 5136c | AJ247258/AJ242462; −/−; AJ247260/N.D. |

| N. mucosa subsp. mucosa | ATCC 19696T, Berger 112, DSM 4631 | AJ247257/AJ242460; −/−; AJ247255/AJ228768 |

| Neisseria perflava | LMG 5284T, Berger 120 | AJ247246/AF124632; −/− |

| Neisseria polysaccharea | ATCC 43768T | N.D./AJ228769 |

| Neisseria sicca | LMG 5290T | AJ247248/AJ228770 |

| Neisseria subflava | LMG 5313T | AJ247249/AJ228771 |

| N. weaveri [Anderson] | ATCC 51223T | AJ247250/AJ228772 |

| N. weaveri [Holmes] | LMG 5135T, ATCC 51462 | AJ247251/AF124633; −/− |

| Oligella ureolytica | LMG 6519T | AJ247261/AF124621 |

| Oligella urethralis | DSM 7531T, Oslo 1098 | AJ247262/AF124622; AJ247263/N.D. |

| Psychrobacter immobilis | DSM 7229T | AJ247264/AF124623 |

| Psychrobacter phenylpyruvicus | Oslo A9911 | AJ247266/AJ242462 |

| Suttonella indologenes | DSM 8309T | AJ247267/AF124625 |

T designates the type strain of this species; −, sequence determined but not submitted to EMBL because another species sequence was identical and already submitted; N.D., sequence not determined; subsp., subspecies. ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; Berger, Ulrich Berger Neisseriaceae strain collection, Heidelberg, Germany; CCUG, Culture Collection University of Göteborg; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Gent (Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms); NCTC, National Collections of Type Cultures; Oslo, Oslo strain collection; Wue, Würzburg strain collection. Multiple 16S/23S groups in column 3 correspond to strains in column 2.

Moraxella lacunata is proposed to consist of at least two subspecies, i.e., subsp. lacunata (small colony variant or group II) and subsp. liquefaciens (large colony variant or group I) (24).

No phenotypic information available to classify this strain as a N. mucosa subspecies.

In vitro amplification and DNA sequencing of the 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes.

A loopful of bacterial cells for extraction of DNA was washed with distilled water and incubated in 200 μl Tris-EDTA buffer for 10 min at 100°C. The suspension was vortexed and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 1 min. Two microliters of the supernatant were used for PCR amplification. PCR was performed in a total volume of 50 μl containing 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 5 pmol of each primer, 5 μl of 10-fold concentrated polymerase synthesis buffer, and 1 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (PE Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). Thermal cycling reactions consisted of an initial denaturation (80°C, 5 min) followed by 28 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 0.45 min), annealing (53°C or 60°C for 16S or 23S rDNA PCR, respectively, 1 min), and extension (72°C, 1.5 min), with a single final extension (72°C, 10 min). Reactions took place in a dedicated automated DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp 2400, PE Biosystems). Negative controls containing water in place of template DNA were run in parallel in each run. The amplicons were sequenced with the PCR primers using the Taq-cycle (Big)-DyeDeoxy Terminator kit and the protocol recommended by the manufactor (PE Biosystems). Centri-Sep columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, N.J.) were used for purifying the sequencing products. Sequences were determined by electrophoresis with the ABI Prism 377 or 310 semiautomated DNA sequencers (PE Biosystems). The nucleotide sequences from both DNA strands were determined in this manner. The broad-range primers SSU-bact-27f (5′- AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG -3′) and SSU-bact-519r (5′-GWA TTA CCG CGG CKG CTG -3′) reported by Lane (15) were applied for 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) PCR and sequencing, whereas the universal primers LSU-bact-1399f (5′- GAT GGG AAR CWG GTT AAT ATT CC-3′) and LSU-bact-1602r (5′- CAC CTG TGT CGG TTT SGG TA -3′) were used for amplification and sequencing of 23S rDNA. Identical or near-identical 23S rDNA primer binding sites have already been described by Van Camp et al. (36) and by Ludwig et al. (16). Ambiguities were resequenced and at least 98% percent of the complete double-stranded sequences of the 16S and 23S rDNA targets were obtained.

Analysis of the rDNA sequences.

The region from base positions 54 to 510 for the 16S rDNA and the region from positions 1400 to 1600 for the 23S rDNA were analyzed (corresponding to Escherichia coli 16S and 23S rDNA positions, respectively). Sequences from primer regions were therefore not included in this analysis. Sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W program (34). This program was also used to construct phylogenetic trees from distance matrices using the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (28) with the correction for multiple substitutions option turned off. The mean sequence divergence level within each taxon and between each pair of related taxa and genera was calculated as the mean of all pairwise comparisons.

EMBL accession numbers for the partial sequences of the 16S and 23S rDNA genes in the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae strains investigated in this study are listed in Table 1. The EMBL accession numbers for the 16S rDNA sequences used to determine error rates in public databases are as follows: Acinetobacter baumannii X81660, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus X81661, Acinetobacter haemolyticus X81662, Acinetobacter johnsonii X81663, Acinetobacter junii X81664, Acinetobacter lwoffi X81665, Acinetobacter radioresistens X81666, Chromobacterium violaceum M22510, Eikenella corrodens M22512, Iodobacter fluviatile M22511, Kingella kingae M22517, Moraxella catarrhalis U10876, Moraxella lacunata D64049, Neisseria animalis L06172, Neisseria canis L06170, Neisseria elongata subsp. elongata L06171, Neisseria macacae L06169, Neisseria weaveri L10738, and Suttonella indologenes M35015.

RIDOM implementation.

The software selected for the RIDOM project had to be freely available for academic use as well as efficient and applicable without the need of a specific platform. FASTA version 2.0 is used for similarity searches, whereas CLUSTAL W version 1.7 is utilized for constructing multiple alignments and nearest-neighbor trees (22, 34). C-source code is available in the case of both programs. Phylogenetic trees are drawn with the aid of DRAWTREE version 3.5 of the PHYLIP software package (7). A MySQL (MySQL AB, Stockholm, Sweden) database holds all taxonomic, disease-related, and species information. Depending on the user query results, dynamically generated HTML pages are published with the aid of an APACHE HTTP server. The database, FASTA, and CLUSTAL W are linked to the common gateway interface of the Web server using programmed Perl script, which also interprets similarity search results. The client's World Wide Web browser should support at least HTML version 3.2. Some HTML extensions such as JavaScript, frames, and cascading style sheets are used occasionally for greater clarity of presentation. These extensions, however, are not essential and therefore older browsers can also be used. Due to the frequent use of tables, however, text-only browsers such as Lynx are not well suited to the task of viewing the contents of RIDOM.

RESULTS

A total of 202 nucleotides of the 23S rRNA gene from 94 isolates and 457 bp of the 16S rDNA from 90 Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae strains were determined by direct DNA sequencing (Table 1). When compared to the type species of the genera Acinetobacter, Moraxella, and Neisseria, an average of 30 polymorphic positions were observed within the partial 16S rDNA for each species and an average of 11 polymorphic positions were observed within the 202 nucleotides of the 23S gene (Table 2). Some of the polymorphic positions were found to be species specific, and a subset of these were present in every isolate of the species concerned (conserved polymorphism). It is interesting that differences in diversity within a species group were observed, depending on which gene was being considered. For example, in the case of N. mucosa, four and three alleles were observed for the 16S and 23S genes, respectively, whereas M. lacunata exhibited two and three alleles, respectively. On the other hand, the complexity of N. meningitidis and N. weaveri were similar, as exemplified by the number of alleles observed for the 16S and 23S genes. In this context alleles are defined as observed rDNA sequence differences of different isolates of the same species, as determined by direct sequencing of PCR products (10).

TABLE 2.

Analysis of polymorphisms in the 16S and 23S rRNA genes of Acinetobacter, Neisseria, and Moraxella species

| Speciesa | No. of isolates | Alleles

|

Total no. of polymorphic positions

|

Species-specific polymorphismsb

|

Species-specific conserved polymorphismsc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | 23S | 16S | 23S | 16S | 23S | 16S | 23A | ||

| A. baumanni | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 5 | − | − |

| A. haemolyticus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 0 | − | − |

| A. johnsonli | 2 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| A. junii | 2 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| A. lwoffii | 5 | 3 | 2 | 47 | 17 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| A. radioresistens | 2 | 2 | 2 | 33 | 21 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| ACINETOBACTER (MEAN ± SD) | 1.67 ± 0.82 | 1.33 ± 0.52 | 27.83 ± 10.69 | 11.67 ± 5.85 | 4.50 ± 5.68 | 2.67 ± 2.39 | 2.50 ± 3.11 | 2.25 ± 2.63 | |

| M. (B.) catharralis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 37 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| M. (B.) caviae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 18 | 2 | 3 | − | − |

| M. (B.) ovis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 29 | 12 | 3 | 1 | − | − |

| M. (M.) bovis | 2 | 1 | 2 | 25 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. (M.) canis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 38 | 19 | 3 | 1 | − | − |

| M. (M.) equi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | − | − |

| M. (M.) lacunata | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. (M.) lincoinii | 1 | 1 | 1 | 45 | 26 | 12 | 8 | − | − |

| M. (M.) nonliquefaciens | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. (M.) osloensis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 58 | 15 | 19 | 2 | − | − |

| MORAXELLA (MEAN ± SD) | 1.20 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.70 | 28.20 ± 9.35 | 14.00 ± 7.54 | 4.2 ± 6.29 | 1.50 ± 2.51 | 0.25 ± 0.50 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| N. animalis | 2 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 19 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| N. canis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 43 | 7 | 10 | 3 | − | − |

| N. cinerea | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N. elongata subsp. elongata | 4 | 3 | 2 | 52 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| N. elongata subsp. glycolytica | 1 | 1 | 1 | 51 | 6 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 51 | 6 | |||||

| N. elongata subsp. nitroreducens | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50 | 6 | ||||

| N. flava | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 5 | 1 | 1 | − | − |

| N. gonorrhoeae | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − |

| N. iguanae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 35 | 6 | 15 | − | − |

| N. lactamica | 2 | 2 | 1 | 36 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| N. macacae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 35 | 5 | 0 | 0 | − | − |

| N. meningitidis | 7 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N. mucosa subsp. heidelbergienis | 5 | 4 | 3 | 58 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 51 | 6 | |||||

| N. mucosa subsp. mucosa | 3 | 2 | 2 | 36 | 7 | ||||

| N. perflava | 2 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N. sicca | 1 | 1 | 1 | 35 | 7 | 0 | 1 | − | − |

| N. subflava | 1 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 4 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| N. weaveri | 3 | 1 | 1 | 31 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 1 | − |

| NEISSERIA (MEAN ± SD) | 1.54 ± 0.92 | 1.27 ± 0.59 | 31.13 ± 15.06 | 8.67 ± 8.83 | 2.13 ± 2.95 | 1.80 ± 3.84 | 0.75 ± 1.39 | 0.63 ± 1.41 | |

| ALL SPECIES (MEAN ± SD) | 1.45 ± 0.77 | 1.32 ± 0.60 | 29.55 ± 15.48 | 10.97 ± 8.06 | 3.26 ± 4.75 | 1.87 ± 3.14 | 1.06 ± 1.91 | 0.88 ± 1.75 | |

Acinetobacter spp. were compared with A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006T, Moraxella spp. were compared with Moraxella lacunata ATCC 17967T, and Neisseria spp. were compared against N. gonorrhoeae DSM 9188T. SD, standard deviation.

Polymorphisms found only in corresponding species.

Polymorphisms found in every isolate analyzed of that species. 0, no conserved polymorphisms; −, no conserved polymorphisms although species-specific polymorphisms were detected.

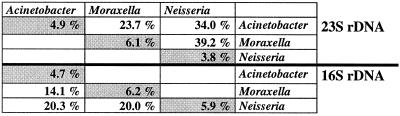

Intraspecies variation for the 16S and 23S genes was highest in A. lwoffii (4.35 and 3.4%), M. lacunata (1.66 and 2.49%), M. catharralis (0.55 and 2.25%) and Neisseria mucosa (1.64 and 1.05%), respectively. Acinetobacter isolates showed the highest average intraspecies variation (2.10 and 1.76%), followed by Moraxella (0.90 and 1.50%) and Neisseria (0.36 and 0.42%), respectively. Interspecies variation within a genus (Fig. 1) ranged from 6.2 to 6.1% for Moraxella spp. to 4.7 to 4.9% for Acinetobacter spp. Interspecies variation between the genera (Fig. 1) ranged from 39.2% for Moraxella and Neisseria spp. 23S rRNA gene sequences to 14.1% for Acinetobacter and Moraxella 16S rRNA gene sequences.

FIG. 1.

Interspecies variation between (white fields) and within (grey fields) genera for 37 isolates of Neisseria (15 different species), 16 isolates of Moraxella (10 species), and 10 isolates of Acinetobacter (7 species). Values are the percent of variation based either on 457 bp in the case of 16S rRNA (bottom) or 202 bp in the case of the 23S rRNA gene (top).

To demonstrate the relationships between species, the aligned DNA sequences were used to produce a distance matrix for pairs of sequences by using the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (28). All species used in this study fell into one of two large groups on the tree. One group included all isolates of the genera Chromobacterium, Eikenella, Iodobacter, Kingella, Neisseria, and Oligella and comprises the β subclass of the Proteobacteria. The other group contained all isolates of the genera Acinetobacter, Moraxella, Psychrobacter, and Suttonella and constitutes the γ subclass of the Proteobacteria. It is interesting that Oligella spp. clustered with the β subclass of Proteobacteria according to 16S rDNA sequence analysis, but to a separate group as analyzed by partial 23S rDNA sequences.

N. macacae and N. mucosa subsp. mucosa ATCC 19696 had identical 16S and 23S rDNA sequences. The 23S genes of Moraxella equi, M. lacunata ATCC 17967, and of Neisseria elongata subsp. glycolytica and N. elongata subsp. nitroreducens also showed sequence identity. The species clusters were heterogeneous in both genes for A. lwoffii, M. lacunata, and N. mucosa. N. meningitidis isolates failed to cluster in one group only in the case of the 23S rDNA subset. These N. meningitidis isolates grouped neither according to serotypes nor to multilocus enzyme electrophoretic types. No clustering according to the Moraxella subgenera Branhamella or Moraxella could be observed.

The EMBL database contained 19 sequences from the same culture collection strains that covered the 16S rDNA region examined in this study. These sequences were compared against our newly generated sequence chromatograms. The EMBL sequences contained 56 ambiguities, whereas our own sequences showed only 3 ambiguities. Furthermore, we detected eight substitutions, two insertions, and one deletion that could be attributed to possible sequencing errors in these published sequences (i.e., an error rate of 0.78%).

DISCUSSION

Our objective was to find a hypervariable rDNA stretch, flanked by strongly conserved regions, which can be used for molecular species identification of species within the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae families. The longest coherent variable region in the 16S rDNA fulfilling these criteria spans the region from E. coli positions 54 to 510 and in the 23S rDNA spans the region from positions 1400 to 1600 (16). This is well illustrated by the quantitative map of nucleotide substitution rates in bacterial rDNAs published by Van de Peer et al. (37). The inter- and intrageneric relationships of members of the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae were therefore investigated by carrying out comparative sequence analysis of PCR-amplified partial 16S and 23S rDNAs of these regions in a total of 94 strains. An ideal region should show a low intraspecies and a high interspecies variability. When the DNA sequences of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes were used as a measure of the intraspecies and interspecies distances within a genus, no great differences between the two regions could be observed (Fig. 1). Only in the case of the 23S rDNA in Neisseria was the interspecies variation significantly lower than that of the 16S rDNA. The interspecies distances between genera for the 23S rDNA sequences on the other hand, were consistently higher than those for the 16S rDNA. A comparison of an absolute measure (i.e., polymorphic positions), however, showed that 16S rDNA always had significantly more variable positions and this was because the relevant region in the 16S rDNA was more than twice as long as that in the 23S rDNA (Table 2). We therefore concluded that the selected region of the 16S rDNA is more suitable than that of the 23S rDNA for identification purposes because of its greater length.

The intraspecies variation within A. lwoffii alone was nearly as high as the interspecies differences in the genus Acinetobacter in general, with the result that molecular identification of this heterogeneous species will be relatively difficult. This finding pinpoints a potential problem in the interpretation of rDNA sequence analysis and indicates that a reliable classification system will require a complete genetic database. The taxonomy of Acinetobacter is, however, still incomplete and evolving, with only seven species currently named (nomenspecies) out of a total of 18 known genomic species, which indicates that a further subdivision of Acinetobacter species may be needed (5, 13, 38). Another potential limitation of the 16S and 23S rDNA method is the insufficient discriminatory power for recently diverged species, as seen in this study in the case of N. macacae and N. mucosa subsp. mucosa ATCC 19696 (8, 21, 39). On the other hand, these two entities are even by phenotypic means not clearly distinct species. In general, a sequential (e.g., second line) sequencing of the more variable 16S/23S rDNA spacer region (1, 14), and a polyphasic approach (i.e., a combination with other pheno- or genotypic techniques) (31), should solve this problem. A further problem in using the rDNA sequencing approach for identification purposes is the possible intercistronic heterogeneity between different rRNA operons (18). Despite these limitations, DNA sequence-based microbial identification is expected to play a major role in clinical microbiology laboratories in the future because of its speed, reproducibility, and potential for automation. High-quality DNA sequence data, in combination with DNA microarray techniques, may revolutionize diagnostic laboratory procedures (35).

The lack of adequate quality control procedures for public database entries and the associated difficulties when this data is used in medical diagnostics is documented by the high error rates of sequences detected in this study. Therefore, a diagnostic library preferably should rely on culture collection strain sequences and make their primary sequence data (i.e., the sequence chromatograms) available to users for purposes of intersubjective control of their data.

According to 16S rDNA sequences analysis, the genera Chromobacterium, Eikenella, Iodobacter, Kingella, Neisseria, and Oligella form one cluster, which is a part of the β subclass of the Proteobacteria. Acinetobacter, Moraxella, Psychrobacter, and Suttonella are separated into another cluster belonging to the γ subclass of the Proteobacteria (6, 13, 24). Signature sequence positions for these subclasses determined by Woese (41), most notably the E. coli position 485, also support this grouping. In contrast, the relationships among subgroups in our study differ slightly depending on the gene analyzed and also differ from previous results. This might be due to interspecies recombination events, since these species belong to a group of bacteria that frequently exchange chromosomal genes (30).

New RIDOM entries of bacterial genera are compared with the American Society for Microbiology's Manual of Clinical Microbiology to guarantee that all medically relevant pathogens are included (19). For quality control reasons, only sequences from strains held in culture collections are included in the database. In addition, the electropherograms of the sequence are deposited on our World Wide Web server thus allowing detailed comparison of the sequences generated. The classification of species entries is made in accord with the NCBI's “Guidelines and Conventions for the purpose of Biological classification.” Therefore, we implemented the phylogeny tree of the Ribosomal Database Project (17) to reflect current phylogenetic knowledge on prokaryotes. In the case of nomenclatural terms, we adhered as closely as possible to the recommendations of the draft BioCode as found at the Royal Ontario Museum Website (http://www.rom.on.ca/biodiversity/biocode/biocode1997.html). To ensure updated taxonomic entries and avoid outdated nomenclature, bacterial names are checked with the aid of the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen's Bacterial Nomenclature up-to-date database (http://www.dsmz.de/bactnom/bactname.htm), which is based on valid names published in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. The hierarchic ordering and naming of different levels within the “organ-browser” is adapted from the “NLM-MeSH Tree Structures—Category C. Diseases” as found at the National Library of Medicine Website (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/). The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences' International Nomenclature of Diseases (4) and the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (42) were used to relate standardized disease terms to specific microorganisms and to facilitate low background noise links to Internet databases.

The logic incorporated in the recently published and now commercially available MicroSeq system (PE Biosystems, Forster City, Calif.) is comparable to that in the RIDOM system (33). It also uses nonragged 16S rDNA sequences for microbial identification purposes. The database of MicroSeq currently contains over 1200 full-length, high-quality ATCC culture collection bacterial strain sequences. A feature-rich Macintosh analysis software enables the comparison of any unknown sequence with the sequences in the database. However, some fundamental differences exist between the two systems. Most notable of these is the fact that the RIDOM system, due to its open hypertext structure, allows the incorporation of other useful Internet sources. Another important difference is the inclusion of phenotypic methods and non-rDNA targets for species identification purposes (a polyphasic approach). Furthermore, the RIDOM approach is far-reaching in that it not only tries to include sequences and species names in its database but also includes additional information related to taxonomy and disease. Finally, RIDOM is specifically designed for medically important organisms for both humans and animals, whereas MicroSeq in its current form concentrates on environmental isolates for food and pharmaceutical industry quality control needs.

The RIDOM system currently offers the Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae dataset for general use and demonstration purposes, and a rapid and constant increase in the number of entries pertaining to other classes of bacteria and fungi is now under development. If the similarity search score is too low because the species in question is not yet incorporated in our database, the user may directly conduct a search of the NCBI GenBank using NCBI's sequence similarity search tool BLAST. Even if the user has no sequence for comparison, our database can still be searched or an Internet metasearch for species information related to nomenclature, phylogeny, or disease can be carried out. The RIDOM persistent uniform resource locator is http://purl.oclc.org/net/ridom, which is currently associated with the following URL: http://www.ridom.hygiene.uni-wuerzburg.de/. E-mail contact is possible using the address webmaster@ridom.hygiene.uni-wuerzburg.de.

In conclusion, our data show that it is possible to identify most Neisseriaceae and Moraxellaceae species by partial rDNA sequencing and that the 16S rDNA region examined in this study is more suitable for molecular diagnosis than the partial 23S rDNA. A genetic database should be exhaustive, that is, it should include more than just one representative strain of each species. A molecular diagnosis system should involve both different molecular targets and additional analytical procedures, since not all species can be differentiated by partial 16S rDNA sequencing alone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Monika Bergmann, Angelika Hansen, and Marion Patzke-Öchsner of the Institute for Hygiene and Microbiology for their excellent technical assistance. We also thank Jürgen Schoof and Ulrich Vogel for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry T, Colleran G, Glennon M, Dunican L K, Gannon F. The 16s/23s ribosomal spacer region as a target for DNA probes to identify eubacteria. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:51–56. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bøvre K. Proposal to divide the genus Moraxella Lwoff 1939 emend. Henriksen and Bøvre 1968 into two subgenera, subgenus Moraxella (Lwoff 1939) Bøvre 1979 and subgenus Branhamella (Catlin 1970) Bøvre 1979. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1979;29:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bøvre K. Neisseriaceae Prevot 1933. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. 7th ed. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 288–309. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International nomenclature of diseases. II. Infectious diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkshoorn L, van Harsselaar B, Tjernberg I, Bouvet P J M, Vaneechoutte M. Evaluation of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:33–39. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enright M C, Carter P E, MacLean I A, McKenzie H. Phylogenetic relationships between some members of the genera Neisseria, Acinetobacter, Moraxella, and Kingella based on partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:387–391. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox G E, Wisotzkey J D, Jurtshuk P. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identify may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:166–170. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-1-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredricks D N, Relman D A. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:18–33. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gingeras T R, Ghandour G, Wang E, Berno A, Small P M, Drobniewski F, Alland D, Desmond E, Holodniy M, Drenkow J. Simultaneous genotyping and species identification using hybridization pattern recognition analysis of generic Mycobacterium DNA arrays. Genome Res. 1998;8:435–448. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmsen D, Heesemann J, Brabletz T, Kirchner T, Müller-Hermelink H K. Heterogeneity among Whipple's-disease-associated bacteria. Lancet. 1994;343:1288. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmsen D, Rothgänger J, Singer C, Albert J, Frosch M. Intuitive hypertext-based molecular identification of micro-organisms. Lancet. 1999;353:291. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim A, Gerner S P, Liesack W. Phylogenetic relationship of the twenty-one DNA groups of the genus Acinetobacter as revealed by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:837–841. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen M A, Webster J A, Straus N. Rapid identification of bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:945–952. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.945-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludwig W, Dorn S, Springer N, Kirchhof G, Schleifer K H. PCR-based preparation of 23S rRNA-targeted group-specific polynucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3234–3244. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3236-3244.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The RDP (ribosomal database project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Murcia A J, Anton A I, Rodriguez-Valera F. Patterns of sequence variation in two regions of the 16S rRNA multigene family of Escherichia coli. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:601–610. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washinghton, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen G J, Woese C R, Overbeek R. The winds of (evolutionary) change: breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.1-6.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palys T, Nakamura L K, Cohan F M. Discovery and classification of ecological diversity in the bacterial world: the role of DNA sequence data. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1145–1156. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettersson B, Kodjo A, Ronaghi M, Uhlen M, Tønjum T. Phylogeny of the family Moraxellaceae by 16S rDNA sequence analysis, with special emphasis on differentitation of Moraxella species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:75–89. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Relman D A, Loutit J S, Schmidt T M, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis: an approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1573–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossau R, Van Landschoot A, Gillis M, De Ley J. Taxonomy of Moraxellaceae fam. nov., a new bacterial family to accommodate the genera Moraxella, Acinetobacter, and Psychrobacter and related organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:310–319. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossau R, Vandenbussche G, Thielemans S, Segers P, Grosch H, Gothe E, Mannheim W, De Ley J. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistron similarities and deoxyribonucleic acid homologies of Neisseria, Kingella, Eikenella, Simonsiella, Alysiella, and Center for Disease Control groups EF-4 and M-5 in the emended family Neisseriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah H N, Gharbia S E, Collins M D. The gram-stain, a declining synapomorphy in an emerging evolutionary tree. Rev Med Microbiol. 1997;8:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith N H, Holmes E C, Donovan G M, Carpenter G A, Spratt B G. Networks and groups within the genus Neisseria: analysis of argF, recA, rho, and 16S rRNA sequences from human Neisseria species. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:773–783. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stackebrandt E, Goebel B M. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:846–849. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stackebrandt E, Murray R G E, Trüper H G. Proteobacteria classis nov., a name for the phylogenetic taxon that includes the “purple bacteria and their relatives.”. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Y W, Ellis N M, Hopkins M K, Smith D H, Dodge D E, Persing D H. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic techniques for identification of unusual aerobic pathogenic gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3674–3679. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3674-3679.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Troesch A, Nguyen H, Miyada C G, Desvarenne S, Gingeras T R, Kaplan P M, Cros P, Mabilat C. Mycobacterium species identification and rifampin resistance testing with high-density DNA probe arrays. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:49–55. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.49-55.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Camp G, Chapelle S, De Wachter R. Amplification and sequencing of variable regions in bacterial 23S ribosomal RNA genes with conserved primer sequences. Curr Microbiol. 1993;27:147–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01576012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van de Peer Y, Chapelle S, De Wachter R. A quantitative map of nucleotide substitution rates in bacterial rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3381–3391. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaneechoutte M, Dijkshoorn L, Tjernberg I, Elaichouni A, de Vos P, Claeys G, Verschraegen G. Identification of Acinetobacter genomic species by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:11–15. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.11-15.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vedros N A, Hoke C, Chun P. Neisseria macacae sp. nov., a new Neisseria species isolated from the oropharynges of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1983;33:515–520. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson K H, Blitchington R, Frothingham R, Wilson J A. Phylogeny of the Whipple's-disease-associated bacterium. Lancet. 1991;338:474–475. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th rev. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]