Abstract

The viability of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is critically dependent upon staving off death by apoptosis, a hallmark of CLL pathophysiology. The recognition that Mcl-1, a major component of the anti-apoptotic response, is intrinsically short-lived and must be continually resynthesized suggested a novel therapeutic approach. Pateamine A (PatA), a macrolide marine natural product, inhibits cap-dependent translation by binding to the initiation factor eIF4A. In this study, we demonstrated that a synthetic derivative of PatA, des-methyl des-amino PatA (DMDAPatA), blocked mRNA translation, reduced Mcl-1 protein and initiated apoptosis in CLL cells. This action was synergistic with the Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-199. However, avid binding to human plasma proteins limited DMDAPatA potency, precluding further development. To address this, we synthesized a new series of PatA analogs and identified three new leads with potent inhibition of translation. They exhibited less plasma protein binding and increased cytotoxic potency toward CLL cells than DMDAPatA, with greater selectivity towards CLL cells over normal lymphocytes. Computer modeling analysis correlated their structure-activity relationships and suggested that these compounds may act by stabilizing the closed conformation of eIF4A. Thus, these novel PatA analogs hold promise for application to cancers within the appropriate biological context, such as CLL.

Keywords: translation inhibition, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, pateamine A (PatA), des-methyl, des-amino pateamine A (DMDAPatA), eIF4A

Introduction

Dysregulation of mRNA translation is a crucial feature of cancer. Alterations in the components of the translational machinery, including the translation factors and regulators, are commonly associated with cancer development and progression.1 mRNA translation is the nexus that integrates signals from multiple signaling pathways, and is connected to many hallmarks of cancer such as aberrant proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis.1 Therefore, targeting translation machinery holds great promise in cancer therapeutics. To this end, homoharringtonine, an inhibitor of translation elongation, was approved for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, and thus became the first translation inhibitor in the clinic.2

Among the phases of translation: initiation, elongation, termination and ribosome recycling, initiation is the most regulated and rate-limiting. The formation of the eIF4F complex, which prepares the mRNA for the incoming ribosome subunits, is the essential step for initiation, and thus a valid target for therapeutics.1 eIF4F is comprised of the scaffold protein eIF4G, the cap-binding protein eIF4E, and the helicase eIF4A. The most successful examples of agents acting through eIF4F are the rapalogs that inhibit mTORC1, which phosphorylates the eIF4E binding protein 4E-BP, leading to the release and activation of eIF4E to facilitate eIF4F assembly.3, 4 In addition, mTORC1 also phosphorylates and activates eIF4G and S6 kinase, which in turn activates eIF4A. Currently, rapalogs such as temsirolimus and everolimus have been approved for the treatment of breast and renal cancers and mantle cell lymphoma.5

Several natural products comprise a group of small molecules that function as inhibitors of eIF4A.6 eIF4A is well characterized as a RNA-dependent ATPase and an ATP-dependent RNA helicase. It unwinds the secondary structure of mRNA at the 5’ terminus to facilitate ribosome binding. Inhibition of the RNA binding activity of eIF4A by hippuristanol suppressed proliferation and induced apoptosis in T-cell leukemia.7 The tropical plant derived eIF4A inhibitor, silvestrol, exhibited anticancer activities in both leukemia and solid tumor models.8 Silvestrol acts by stimulating the RNA binding of eIF4A and sequestering eIF4A from the formation of the eIF4F complex.8

Pateamine A (PatA, 1) is another natural product that binds to eIF4A and inhibits translation initiation. It was isolated from the New Zealand marine sponge Mycale sp..9 Originally thought to be an immunosuppressant to block T cell activation and T cell receptor mediated IL-2 production,10 PatA also demonstrated inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in several cancer cell lines.11 Subsequently, PatA was found to be a potent inhibitor of translation initiation through binding to eIF4A.12–15 Similar to the case of silvestrol, rather than inhibiting eIF4A, PatA tightened its RNA binding, which is coupled with enhanced ATPase and helicase activities. This action sequestered eIF4A on mRNA, and thus prevents the recycling of eIF4A to form the eIF4F complex.13,16

Although natural products are an enduring class of privileged structures that possess a wide range of biological and medicinal properties,17–21 some of them lack the physical properties required for development into drugs. Therefore, much effort has gone into the synthesis of their analogs with the goal to improve their drugability while maintaining or enhancing their biological functions. We reported the first total synthesis of PatA in 1998.10 Subsequently, a simplified analog, des-methyl, des-amino PatA (DMDAPatA, 2, Fig. 3) was synthesized with comparable potency.22, 23 Cell-based assays with DMDAPatA demonstrated potent anti-proliferative activity in vitro against over 30 human cancer lines, including a cell line that overexpressed a multidrug resistance protein.24 This property is preferable over silvestrol, which appears to be a substrate of the multi-drug resistance 1 (MDR1) efflux pump.25 Xenograft studies in mice showed DMDAPatA had potency against human leukemia and melanoma, and sensitized non-small cell lung cancer cells to radiation.26

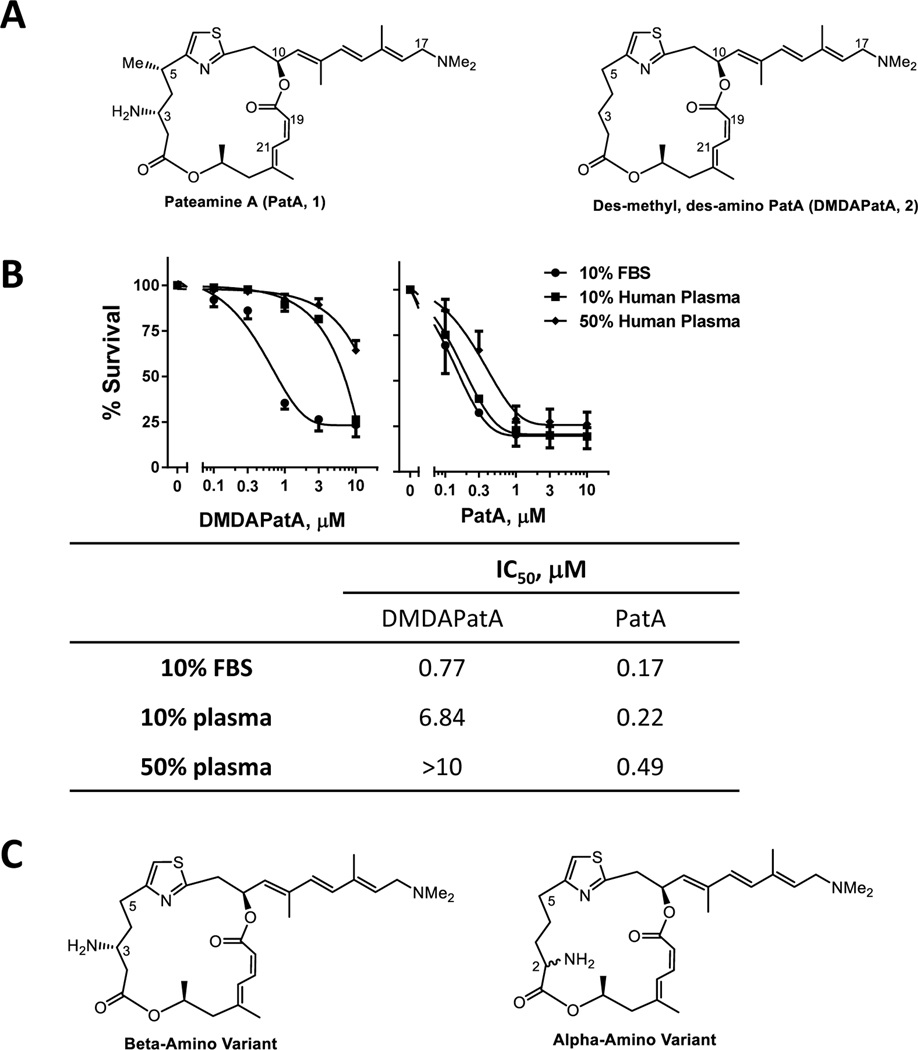

Figure 3. Human plasma greatly impacted the potency of DMDAPatA.

A. Chemical structures of PatA (1) and DMDAPatA (2). B. Comparison of toxicity of DMDAPatA and PatA in CLL cells incubated in media supplemented with either 10% FBS, 10% patient plasma or 50% patient plasma. Cell death was measured by annexin V/PI positivity at 24 h (mean ± SE, n=3). The IC50 values for induction of cell apoptosis were summarized below the graphs. C. Structures of the beta-amino and alpha-amino variants of PatA to indicate the locations where the structural modifications were made.

The present study extended the investigation of DMDAPatA in a different biological context: primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). These cells are characterized by their critical dependence of the sustained expression of anti-apoptotic proteins for survival.27, 28 One such protein, Mcl-1, is intrinsically short-lived; thus its level is very sensitive to inhibitors of protein biosynthesis. Our previous work demonstrated that transient exposure to inhibitors of transcription or translation, such as flavopiridol,29 SNS-03230 and homoharringtonine,31 efficiently induce apoptosis in the CLL cells through depletion of Mcl-1. When tested in primary CLL cells, DMDAPatA demonstrated inhibition of protein synthesis, reduction of Mcl-1 and initiation of apoptosis. However, our studies suggested that DMDAPatA is highly protein bound in human plasma and may lack sufficient in vivo potency required for development as a therapeutic agent. To address this, we synthesized a new series of PatA analogs with the goal of improving the physical properties and CLL potency.

Materials and methods

Patients

Fresh blood samples from 45 CLL patients were used in this study (Supplemental Table 1), including 23 male and 22 female patients with a median age of 67 years (range 48 to 81 years old). Their median white blood cell (WBC) count was 63 000/μl (range, 26 600 to 343 300/μl), with median lymphocyte percentage of 89% (range, 69% to 98%). The authors were blind about the biological features of the samples as well as the treatment history of the patient when performing the in vitro experiments. Approval was obtained from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board for this investigation, and all patients agreed to participate and provided informed consent for use of their cells for in vitro studies.

Evaluation of combination:

The combination analysis of DMDAPatA (2) and ABT-199 was performed by measuring cell death after 24 h incubation with each drug or in combination. The combination was carried out in a fixed ratio of concentrations based on the IC50 values of each individual compound. The CLL cells were cultured on top of the StromaNKtert layer to maintain cell viability for the duration of the experiment. The combination index (CI) was analyzed using the median-effect method32, 33 using the CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Dose reduction index was used to demonstrate the mutual potentiation of each compound when used in combination.

Computational Modeling

A homology model of the human eIF4A1 (P60842) protein was built starting from the crystal structure of the human exon junction complex with a trapped DEAD-box helicase (eIF4A3) bound to a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog and a short sequence of mRNA in a closed conformation, using MOE 2016.08 software.34 Binding sites for PatA analogs were predicted using MOE’s Site Finder tool. Based on literature data and prediction results, a binding site located between the ATP binding site and the RNA binding site was selected for docking studies.12, 14, 16, 22, 23, 35 PatA analogues were docked into the predicted binding site using the proxy triangle placement method available in MOE. These methods are described in detail in the supplemental material and methods.

Results

Mechanism of DMDAPatA (2) induced apoptosis in primary CLL cells:

DMDAPatA inhibited protein synthesis in primary CLL samples as soon as 4 h after exposure (Fig. 1A), supporting its role as a translation inhibitor. Further, DMDAPatA reduced levels of the short-lived anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 (Fig. 1B). Neither the levels of Bcl-2 nor Bcl-XL were affected by DMDAPatA, which is consistent with the longer half-lives of these proteins.36 Since Mcl-1 blocks apoptosis by preventing BAX and BAK from forming pores on the mitochondrial membrane, diminishing Mcl-1 with DMDAPatA induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). This was demonstrated by the loss of binding of the cationic dye DiOC6(3) (Fig. 1C, top). The IC50 for MOMP induction averaged 4.92 ± 1.40 μM (mean ± SD) in 15 CLL samples (Fig 1D). MOMP facilitates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to form the apoptosome, which activated caspase-3 and induced apoptosis. As PARP is a substrate of caspase 3, an increase of cleaved PARP in Fig. 1B indicated the activation of caspase 3. A flow cytometry analysis by annexin V and PI double staining demonstrated induction of apoptosis by DMDAPatA (Fig 1C, bottom), with an average IC50 of 5.21 ± 1.53 μM (mean ± SD, n=15) (Fig 1D). Although the sensitivity to DMDAPatA varied among patient samples, the IC50 values were not significantly different in samples from CLL patients with poor prognostic characteristics (such as a β2-microglobulin (B2M) of >4, advanced Rai stage (3–4), unmutated IgHV gene, positive for ZAP-70 expression or deletion/mutation of the TP53 gene) compared to samples with favorable prognosis (Fig. 1E). One sample with 19% del11q had a similar IC50 to DMDAPatA (4.32 μM) compared to other samples (not shown). Six patients received prior treatment containing either CD20 antibodies, revlimid or fludarabine, cytoxan & rituximab (FCR). Their IC50 values were not significantly different from those of the treatment naïve samples.

Figure 1. Mechanism of DMDAPatA (2) induced apoptosis in the primary CLL cells.

A. DMDAPatA inhibited RNA synthesis in the CLL cells. RNA synthesis, demonstrated by the percentage of [3H]leucine incorporation of untreated controls, was measured in the CLL cells at 4 and 24 h after incubation with DMDAPatA. Data represents mean ± SE from two CLL samples each performed in triplicates. B. DMDAPatA reduced the protein levels of Mcl-1 and induced PARP cleavage, an indicator of apoptosis, without affecting the expression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL. A representative immunoblot from 3 CLL samples is shown. C. A set of flow cytometry plots showing loss of mitochondria membrane potential (reduction of DiOC6(3) binding) and induction of apoptosis (Annexin V positivity) by DMDAPatA (10 μM, 24 h). D. A dose response curve of DMDAPatA to induce CLL cell death at 24 h. Cell death was measured by both DiOC6(3) and Annexin V staining (mean ± SE, n=15). E. DMDAPatA induces apoptosis in the CLL cells regardless of patient prognosis characteristics or treatment history. The IC50 values were compared in different groups with poor (open symbols) or favorable (closed symbols) prognosis. None of the comparison was significant by unpaired t test. Similar variance were found between groups that were compared. The bars represent the median values of each group. B2M: β2-microglobulin, mg/L; Rai: Rai stage; IgHV: mutation status of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable-region (IgHV) gene; ZAP70: expression of the ZAP70 protein; p53: deletion or mutation of the TP53 gene. The number of samples in each group is shown above the plot.

Synergistic combination of DMDAPatA (2) with ABT-199.

Both Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 are pro-survival proteins that regulate apoptosis by interacting with the BH3 motifs of their pro-apoptotic partners. The BH3 mimetic, ABT-199, binds with high affinity to Bcl-2 and blocks this interaction, but does not bind to Mcl-1. Resistance to BH3 mimetics was associated with upregulation of Mcl-1.37–39 Because DMDAPatA depleted Mcl-1 without affecting Bcl-2 expression, we hypothesized that the combinations of DMDAPatA and ABT-199 would target the two parallel arms of apoptosis control and kill the CLL cells synergistically. Indeed, a median effect analysis in four CLL samples demonstrated that DMDAPatA and ABT-199 exhibited strong synergy (combination index less than 1) (Fig. 2A, top). For a more straightforward demonstration of the synergistic effect, we compared the IC50 values of each compound alone and in combination (Fig. 2B). The combination clearly reduced the IC50 values of both compounds. The dose reduction index, a measurement of how much the dose of a compound could be reduced with a combination to reach the same effect, was calculated at various levels of cell killing (Fig. 2A, bottom). The addition of ABT-199 resulted in a 2–3 fold reduction of the IC50, IC75 and IC90 of DMDAPatA. Conversely, combination with DMDAPatA reduced IC50, IC75 and IC90 of ABT-199 by 7.6, 23 and 67 fold, respectively. These analyses demonstrated mutual potentiation of these compounds, thus providing rationale for future clinical combinations of DMDAPatA and analogs with inhibitors that antagonize Bcl-2 activity.

Figure 2. Synergistic combinations of DMDAPatA (2) and ABT-199.

A. A median-effect curve showing synergistic combinations of DMDAPatA and ABT-199 (n=4). Dose reduction index values of each compound at IC50, IC75 and IC90 were listed below the graph. B. The comparison of IC50 values of DMDAPatA and ABT-199 when used alone or in combinations in the four CLL samples.

Limitations of DMDAPatA (2).

A direct comparison of DMDAPatA to its parental compound PatA (1, chemical structures in Fig. 3A) showed that DMDAPatA is similarly potent as PatA in growth media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, a culture condition commonly used in the in vitro studies (Fig. 3B). However, when assayed against CLL cells cultured in media supplemented with 10% autologous patient plasma, DMDAPatA was about 30 times less potent than PatA. The IC50 was 6.88 μM for DMDAPatA and 0.20 μM for PatA, respectively. Further increasing plasma content in the media led to even greater loss of potency of DMDAPatA. In contrast, the presence of patient plasma in the media was not as influential to the IC50 values of PatA. We previously determined that the stability of DMDAPatA is similar in human serum and fetal bovine serum.23 In terms of plasma protein binding, we found that PatA was 97.4% and 98.7% bound to human serum and FBS, with 80.4% and 86.2% recovery rates respectively, after 22 h incubation with the serum (Table 1). DMDAPatA was 99.7% and 99.1% bound to human and bovine serum, respectively. The recovery rate of DMDAPatA in human serum was significantly less (31.4%) compared to that in FBS (78.3%). A low recovery rate does not affect the accuracy of binding measurement,40 but is likely a result of avid binding to human plasma proteins, which may have limited the amount of free DMDAPatA to exert its toxicity toward CLL cells. Thus, although DMDAPatA demonstrated activity as a protein synthesis inhibitor in CLL cells, its decreased potency in human plasma may diminish enthusiasm for its further development. This suggested that the synthesis of novel analogs is required with optimized properties and efficacy.

Table 1:

Structure-activity relationship of the PatA analogs and their plasma protein binding properties.

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Compounds | Structure | IC50, μMa | Human serum protein binding (%) b | FBS protein binding (%)b | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | 10% FBS | 10% Plasma | Fraction Bound | Recovery | Fraction Bound | Recovery | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| PatA (1) | NH2 | Me | H | H | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | 97.4 ± 0.6 | 80.4 ± 12.8 | 98.7 ± 0.6 | 86.3 ± 4.3 | |

| DMDA PatA (2) | H | H | H | H | 0.64 ± 0.29 | 4.54 ± 1.92 | 99.6 ± 0.1 | 38.1 ± 7.5 | 99.1 ± 0.1 | 78.3 ± 2.7 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| β-amino variants | 3 | NH2 | H | H | H | 0.30 ± 0.27 | 0.33 ± 0.25 | 86.7 ± 4.7 | 54.0 ± 2.6 | ||

| 4 | NHTCBoc | H | H | H | 2.97 ± 2.64 | 6.71 ± 3.63 | |||||

| 5 | NHAc | H | H | H | 5.60 ± 6.64 | 7.01 ± 1.78 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| α-amino variants | S configuration | ||||||||||

| 6 | H | H | NHBoc | H | 0.83 ± 0.18 | 2.23 ± 1.10 | 99.6 ± 0.1 | 92.7 ± 3.9 | |||

| 7 | H | H | NHCOCF3 | H | 0.55 ± 0.19 | 1.95 ± 1.60 | 99.3 ± 0.0 | 85.3 ± 2.3 | |||

| 8 | H | H | NHAc | H | 0.26 ± 0.24 | 0.56 ± 0.39 | 78.0 ± 7.2 | 33.7 ± 1.2 | |||

| 9 | H | H | NHSO2Me | H | 0.35 ± 0.33 | 1.00 ± 0.90 | 94.0 ± 2.6 | 45.7 ± 1.5 | |||

| 10 | H | H | NH2 | H | 2.47 ± 1.05 | 3.68 ± 1.95 | |||||

| 11 | H | H | NHTCBoc | H | 3.59 ± 0.46 | 6.81 ± 0.87 | |||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| R configuration | |||||||||||

| 12 | H | H | H | NHTCBoc | 1.88 ± 0.41 | 5.42 ± 0.24 | |||||

| 13 | H | H | H | NHAc | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 93.9 ± 1.0 | 21.8 ± 0.1 | 95.6 ± 0.2 | 80.8 ± 1.9 | |

Data represent the mean IC50 values ± SD measured in least 3 individual CLL samples.

Data represent mean ± SD in triplicate measurements.

Design, synthesis and biological screening of the new PatA analogs.

We introduced an amino group at either the C2 (alpha-amino variant) or C3 position (beta-amino variant) of the macrocycle (Fig. 3C), with the anticipation to lower lipophilicity (characterized by the octanol-water partition coefficient LogP) which correlates with reduced plasma protein binding.41, 42 The reduced lipophilicity may also lead to increased aqueous solubility, better permeability and dissolution.43 An abbreviated description of the synthesis of the alpha-amino variant (2-amino-DMPatA) and beta-amino variant, des-methyl PatA (DMPatA) is shown with key fragments and synthetic steps (Supplemental Fig. 1). Using this strategy, we synthesized eleven new derivatives including three beta-amino variants and eight alpha-amino variants (Table 1). We screened their potency by measuring their IC50s against the primary CLL cells at 24h. The most potent analog in the beta-amino series is the free amine des-methyl PatA (DMPatA 3, R1 = NH2) with similar activity to PatA (Table 1). Derivatives of the amine (4 and 5) with a carbamate or acetamide functional group are significantly less active than the free amine. In the alpha-amino series, six analogs were prepared with the S configuration at C2 and two with the R configuration 12 and 13. The four analogs with small polar groups attached to the amino functionality in the S configuration (6, 7, 8 and 9) are significantly more active than DMDAPatA. Derivatives 8 and 9 are the most potent analogs in this series, with 8 approaching the level of activity of the natural product PatA. The free amine (10, R3 = NH2) and the bulky TCBoc derivative 11 are relatively less active. The R configuration at C2 seems to improve activity when 13 was compared to its diastereomer 8, when assayed in FBS. However, both compounds appear equipotent when screened in the presence of human plasma.

Additional characterization of the analogs.

Based on this initial screening, 6 compounds (3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 13) were selected for additional evaluation of their drugability. We started with assessing plasma protein binding properties of these analogs (Table 1). Compared to DMDAPatA, 6 and 7 showed great improvement in percent recovery, but still had relatively high protein binding in human plasma. PatA derivatives 3, 8 and 9 have much lower plasma protein binding than both PatA and DMDAPatA with modest recovery. Analog 13 displayed over 90% plasma protein binding in both human and bovine serum, and a very low rate of recovery in human plasma (21.8%), possibly indicating a lack of stability in human plasma. Therefore, three new analogs, 3, 8 and 9 became our best development candidates.

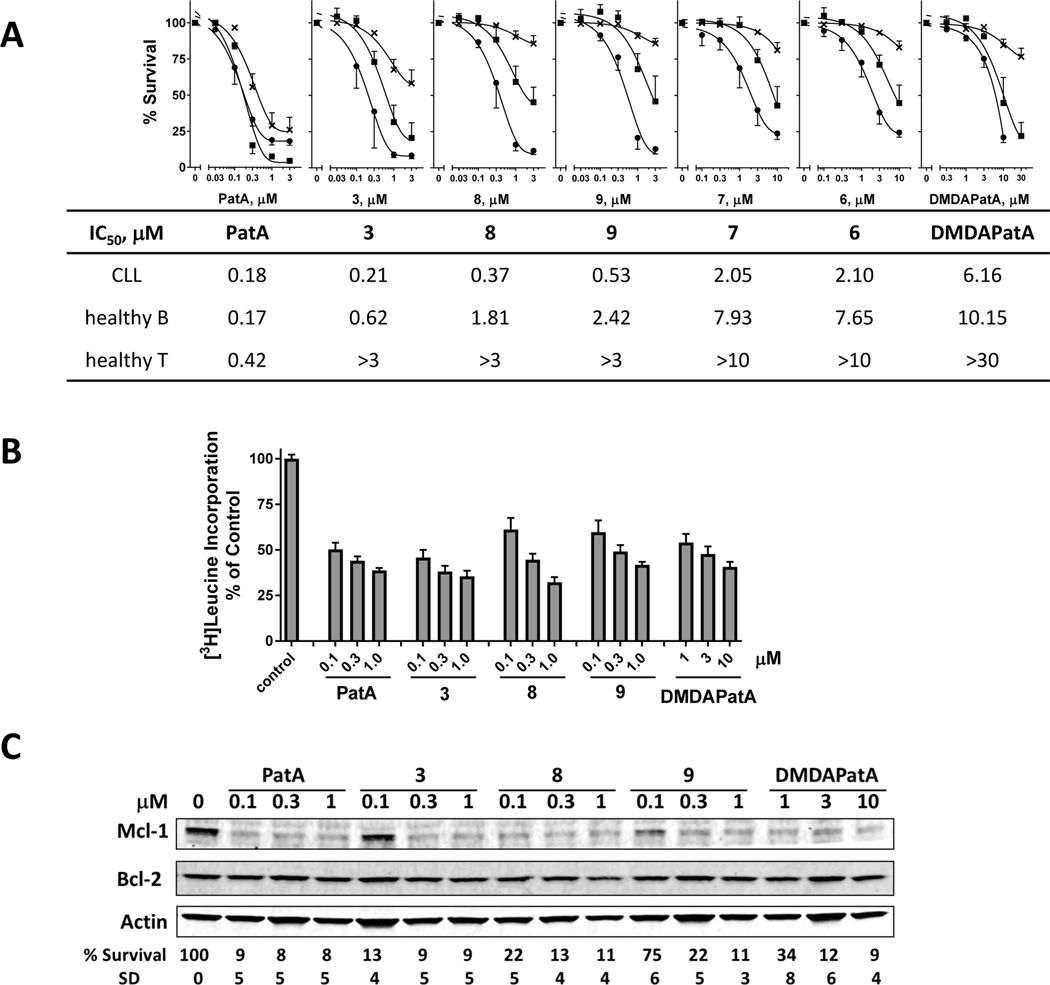

To predict the therapeutic window of the new PatA analogs, we compared their cellular toxicity to CLL cells and to B and T cells from healthy donors (Fig. 4A). Our data showed that PatA was similarly toxic to CLL cells as well as normal B and T cells. PatA was originally identified as a molecule that inhibits T cell activation, consistent with its toxicity to T cells.10 It is encouraging that all of the new PatA analogs demonstrated greatly reduced T cell toxicity, as well as lower potency toward B cells from healthy donors, indicating a significant improvement in therapeutic window.

Figure 4. The new PatA analogs inhibit protein synthesis and demonstrate improved selectivity toward the CLL cells.

A. Toxicities of the PatA analogs toward either the CLL cells (●), or the B (■) and T (×) cells from healthy donors (mean ± SE, n=3 except for 5 and 6 CLL samples were used for PatA and DMDAPatA, respectively ). The IC50 values were summarized below the graph. B. All PatA analogs inhibited of protein synthesis in primary CLL cells. Protein synthesis, demonstrated by percentage of [3H]leucine incorporation of untreated controls, was measured in the CLL cells at 4 h after incubation with PatA analogs. Data represents mean ± SE from three CLL samples each performed in triplicate. C. All PatA analogs reduced the protein levels of Mcl-1, without affecting the expression of Bcl-2. A representative immunoblot from one of three CLL samples were shown. The samples were collected at 24 h after incubating the CLL cells with increasing concentrations of the PatA analogs and then subjected to immunoblotting. The cell viability at the time of sample collecting was listed under the graph (mean % survival and SD, n=3).

To confirm that the new analogs retain their cytotoxic effects through inhibition of protein synthesis, we performed [3H]leucine incorporation analysis on the three most promising candidates, and compared them to DMDAPatA and PatA. In three CLL samples tested, all analogs demonstrated strong inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 4B). Reduction of Mcl-1 level was confirmed by immunoblots (Fig. 4C) and apoptosis was demonstrated by the reduction of CLL cell survival shown below the blots.

Computer modeling of PatA analogs and eIF4A interaction.

An additional 16 derivatives of PatA were screened against CLL that were less active than DMDAPatA and PatA (Supplemental Table 2). All analogs that lacked the C11-C17 basic side chain were completely inactive at concentrations up to 10 μM, as were derivatives with either a C19-C20 alkyne or a trans (19E)-alkene. The SAR noted above for less active derivatives is consistent with our previous reports of PatA derivatives against the proliferation of the cancer cell lines.23

To gain structural insights into the interaction of PatA analogs with eIF4A, we generated a homology model of the human eIF4A1 using the closed conformation of the eIF4A3 structure (PDB ID: 2HYI)34 as the template with both a small mRNA sequence and the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog bound (Fig. 5A). Although eIF4A1 and eIF4A3 share 65% amino acid similarity, eIF4A1 plays a major role in translation initiation, but eIF4A3 participates in the exon junction complex and functions in RNA metabolism.35, 44 Our model showed similar inter-domain interactions as that found in the eIF4A3 structure. The predicted binding site is located at the interface of the N-terminal domain (NTD) and the C-terminal domain (CTD), in between the RNA and ATP binding sites (Fig. 5A). Our computational studies suggest that the rigid binding domain of the PatA macrolide ring (Fig. 5B)23 binds to the pocket consisting of the His-Ala-Cys-Ile sequence that is highly conserved in all PatA binding proteins.45 The tertiary amine of the side chain resides in a small pocket consisting of NTD residues Gln114, Lys118, Gln115 (Ia motif) and CTD residues Arg319, Met315, Arg316, and Asp312. The flexible region (C1-C5) of the macrolide ring binds towards the RNA binding site that consists of residues Gln308, Lys309, Arg311 (of QxxR motif) from CTD and Gly136, Gly137 (GG motif), Thr138, Asn139, Ala142, Glu143 and Lys146 of the NTD. DMDAPatA (Fig. 5C) as well as our three leads (Fig. 5D–5F) all dock to this binding pocket with poses similar to PatA. Analysis of the binding poses of the inactive derivatives 16 and 17 with a C19–20 (E)-alkene shows a significant difference compared to the poses of active compounds such as PatA. The C18 carbonyl oxygen on the rigid side of the macrocycle is positioned in the opposite orientation of the binding pocket and forms an unfavorable interaction with the hydrophobic sidechain of Ile135; thus revealing why both analogs are not active. The trienyl side chain of PatA (C11–17) interacts with residues from both N- and C- terminal domains and binds toward the ATP binding site. Removing the C15 methyl group on the side chain (19, 20, 23, 24) increases conformational flexibility of the macrocycle. Additionally, all four of these derivatives lack a basic amine at the terminus of the side chain and both of these factors likely contribute to the loss of activity observed. Binding scores of PatA and its derivatives are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Figure 5. Predicted binding of PatA (1) and its analogs with eIF4A.

A. Predicted binding pocket (shown in gray surface) for the PatA analogues in the eIF4A1 homology model. Color coding: N-terminal domain, teal ribbon; C-terminal domain, pink ribbon; ATP, green; RNA, yellow. B-F. Docked pose of Pat A (1) (B), DMDAPatA (2) (C), DMPatA (3) (D), and N-substituted derivatives 8 (E) and 9 (F).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated our continued efforts to characterize and optimize the natural compound PatA. We showed that the previously identified lead analog DMDAPatA induced apoptosis in primary CLL cells through the intrinsic pathway regardless of patient prognostic characteristics. It reduced cellular levels of the short-lived anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1, and acted synergistically with the Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-199. However, DMDAPatA was >99% bound in human plasma, a property that limited its potency and diminished enthusiasm for future development. Consequently, new PatA derivatives were synthesized and several exhibited greater cytotoxic potency toward CLL cells than DMDAPatA and lower human plasma protein binding. These analogs also demonstrated improved selectivity over normal lymphocytes compared to the parent compound, PatA.

In silico modeling analysis showed that PatA’s predicted rigid binding domain22, consisting of C18–25 of the macrocyclic ring, the side chain, as well as the tertiary amine are all required for binding to the predicted binding pocket of eIF4A in its closed conformation. Any modifications in these areas of the chemical scaffold led to poses that did not dock effectively into the binding site, consistent with the observed dramatic loss of activity in our SAR studies (Supplemental Table 2). These analyses lead us to predict that PatA and its analogs may stabilize a closed conformation of eIF4A by interacting with residues of both the N- and C terminal domains. These compounds also interact directly or indirectly with residues involved in binding of ATP and RNA molecules, thus may play a role in altering their binding affinities. This model explains the proposed mechanism of action that PatA may sequester eIF4A on RNA and block its recycling.13, 41 In the presence of PatA, the energy released from ATP hydrolysis may not be sufficient to convert eIF4A to the open conformation to release RNA.46 Further computational and experimental efforts would be needed to prove this hypothesis. In contrast, the proposed scaffolding domain of PatA is more tolerable to modifications.22 All modifications made in this domain have docking scores that are comparable to PatA (Fig. 5, Supplemental Table 2) and it is likely that other pharmacological properties such as cellular permeability or plasma protein binding lead to observed differences in their cellular activities toward CLL.

By introducing an amino group at either the C2 or C3 position of the macrocycle (Fig. 3C), we anticipated lower lipophilicity, which indeed reduced the plasma protein binding (3, 8, 9), and enhanced potency in plasma (Table 1). It is worth noting that 3 differs only from PatA (1) by the absence of a single C5 methyl group, but demonstrates significantly lower toxicity toward normal B and T cells (Fig. 4), suggesting that this methyl group may contribute to off-target toxicity of PatA.

The helicase activity mediated by eIF4A is a key enzymatic reaction during the initiation phase of protein synthesis. Thus, eIF4A has been extensively explored as a druggable target. Compared to the broad translation inhibition by homoharringtonine which inhibits protein synthesis during the elongation phase,31 it is now recognized that mRNAs with a greater degree of complexity in the secondary structure within the 5’-untranslated region are more dependent on the helicase activity of eIF4A, suggesting that they may be selectively sensitive to particular eIF4A inhibitors.47, 48 Importantly, these so called “weak mRNAs” often control key cellular functions such as proliferation, cell cycle, survival or angiogenesis. Thus, it is not surprising that the activity of eIF4A is highly regulated through signaling pathways or by non-coding RNAs. These multiple layers of regulation enable cells to selectively adjust the expression levels of these key proteins in response to environmental changes. As these translational control mechanisms are frequently dysregulated in cancer, it is predicted that eIF4A inhibition by PatA analogs would selectively target proteins that promote tumorigenesis while sparing the house keeping proteins. A second mechanism of selectivity is attributed to the rapid turn-over rate of Mcl-149 mediated by the two PEST sequences in the Mcl-1 protein that signal for its rapid degradation.50, 51 Thus, upon a transient inhibition of translation, Mcl-1 protein is preferentially depleted. Third, CLL cells are primed to cell death, but apoptosis is kept on check by the over-expressed anti-apoptotic proteins.27 As soon as the anti-apoptotic reservoir was reduced by diminishing Mcl-1, the cells died rapidly. The normal cells do not have this addiction to the anti-apoptotic protein and thus were less sensitive to Mcl-1 reduction (Fig. 4A).

In addition to the promising activity of the PatA analogs as a single agent in CLL, because of the strong rationale to inhibit the two arms of the anti-apoptotic apparatus, we studied the combination effect of decreasing Mcl-1 by translation inhibition and blocking the function of Bcl-2 with venetoclax (Fig. 2). As with venetoclax,52 there is also a strong rationale to target both aspects of the pathogenesis of CLL; the constitutive activation of the BCR signaling and the overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins. Thus, decreasing Mcl-1 by translation inhibition will likely interact in a therapeutically positive manner with agents that block the BCR signaling pathway such as the Bruton kinase inhibitors or PI3K inhibitors. Because ibrutinib or idelalisib are not cytotoxic to the CLL cells in vitro,53, 54 these combinations would need to be tested in vivo in animal models and in the clinic.

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that inhibition of mRNA translation through perturbation of eIF4A by PatA analogs is an attractive therapeutic strategy for CLL either alone or in mechanism-based combinations. We have identified three new lead PatA analogs (3, 8 and 9) with potent inhibition of mRNA translation. These compounds hold promise for application of patient-specific disease with the appropriate biological context, such as CLL, in which the leukemia cells are addicted to the sustained expression of Mcl-1 for survival. These results provide a strong basis for further in vivo evaluation of these derivatives with the goal of bringing these drug leads to the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Achnowledgements:

This study was supported in part by research funding to DR and WP from a High-Impact/High-Risk Research Award from The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, RP130660, by the CLL Global Research Foundation and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Moon Shots Program and cancer center support grant P30CA16622.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information can be found online at the Leukemia website.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010. Apr; 10(4): 254–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi V, Plunkett W, Cortes JE. Omacetaxine: a protein translation inhibitor for treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2014. Apr 1; 20(7): 1735–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell 2007. Jul; 12(1): 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009. May; 10(5): 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasolo A, Sessa C. Current and future directions in mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011. Mar; 20(3): 381–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu J, Pelletier J. Targeting the eIF4A RNA helicase as an anti-neoplastic approach. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2015; 1849(7): 781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bordeleau ME, Mori A, Oberer M, Lindqvist L, Chard LS, Higa T, et al. Functional characterization of IRESes by an inhibitor of the RNA helicase eIF4A. Nat Chem Biol 2006. Apr; 2(4): 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bordeleau ME, Robert F, Gerard B, Lindqvist L, Chen SM, Wendel HG, et al. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation modulates chemosensitivity in a mouse lymphoma model. J Clin Invest 2008. Jul; 118(7): 2651–2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northcote PT, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. Pateamine: a potent cytotoxin from the New Zealand Marine sponge, mycale sp. Tetrahedron Letters 1991. 10/28/; 32(44): 6411–6414. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romo D, Rzasa RM, Shea HA, Park K, Langenhan JM, Sun L, et al. Total synthesis and immunosuppressive activity of (−)-pateamine A and related compounds: Implementation of beta-lactam-based macrocyclization. J Am Chem Soc 1998. Dec 2; 120(47): 12237–12254. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood KA, West LM, Northcote PT, Berridge MV, Miller JH. Induction of apoptosis by the marine sponge (Mycale) metabolites, mycalamide A and pateamine. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 2001. Jun; 6(3): 207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bordeleau ME, Matthews J, Wojnar JM, Lindqvist L, Novac O, Jankowsky E, et al. Stimulation of mammalian translation initiation factor eIF4A activity by a small molecule inhibitor of eukaryotic translation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005. Jul 26; 102(30): 10460–10465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Merrick WC, et al. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Molecular cell 2005. Dec 9; 20(5): 709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low WK, Dang Y, Bhat S, Romo D, Liu JO. Substrate-dependent targeting of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A by pateamine A: negation of domain-linker regulation of activity. Chemistry & biology 2007. Jun; 14(6): 715–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Rzasa RM, et al. Isolation and identification of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A as a molecular target for the marine natural product Pateamine A. Methods in enzymology 2007; 431: 303–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordeleau ME, Cencic R, Lindqvist L, Oberer M, Northcote P, Wagner G, et al. RNA-mediated sequestration of the RNA helicase eIF4A by Pateamine A inhibits translation initiation. Chemistry & biology 2006. Dec; 13(12): 1287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans FJ. Natural products as probes for new drug target identification. J Ethnopharmacol 1991. Apr; 32(1–3): 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson EE. Natural products as chemical probes. ACS Chem Biol 2010. Jul 16; 5(7): 639–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod 2012. Mar 23; 75(3): 311–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robles O, Romo D. Chemo- and site-selective derivatizations of natural products enabling biological studies. Nat Prod Rep 2014. Mar; 31(3): 318–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romo D, Liu JO. Editorial: Strategies for cellular target identification of natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2016. May 4; 33(5): 592–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romo D, Choi NS, Li S, Buchler I, Shi Z, Liu JO. Evidence for separate binding and scaffolding domains in the immunosuppressive and antitumor marine natural product, pateamine a: design, synthesis, and activity studies leading to a potent simplified derivative. J Am Chem Soc 2004. Sep 1; 126(34): 10582–10588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low W-K, Li J, Zhu M, Kommaraju SS, Shah-Mittal J, Hull K, et al. Second-generation derivatives of the eukaryotic translation initiation inhibitor pateamine A targeting eIF4A as potential anticancer agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2014; 22(1): 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuznetsov G, Xu Q, Rudolph-Owen L, Tendyke K, Liu J, Towle M, et al. Potent in vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of des-methyl, des-amino pateamine A, a synthetic analogue of marine natural product pateamine A. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2009. May; 8(5): 1250–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SV, Sass EJ, Davis ME, Edwards RB, Lozanski G, Heerema NA, et al. Resistance to the Translation Initiation Inhibitor Silvestrol is Mediated by ABCB1/P-Glycoprotein Overexpression in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells. The AAPS Journal 2011; 13(3): 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh D, Dougan J, Li J, Romo D, Moorman NJ, Graves LM, et al. Des-methyl, Des-amino pateamine A, a Synthetic Analogue of Marine Natural Product Pateamine A, Sensitizes Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells to Radiation and Enhances BAX Expression. Int J Radiat Oncol 2012. Nov 1; 84(3): S701–S702. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letai AG. Diagnosing and exploiting cancer’s addiction to blocks in apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer 2008. Feb; 8(2): 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen R, Plunkett W. Strategy to induce apoptosis and circumvent resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2010. Mar; 23(1): 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen R, Keating MJ, Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Transcription inhibition by flavopiridol: mechanism of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell death. Blood 2005. Oct 1; 106(7): 2513–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Wierda WG, Chubb S, Hawtin RE, Fox JA, Keating MJ, et al. Mechanism of action of SNS-032, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2009. May 7; 113(19): 4637–4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R, Guo L, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Wierda WG, Plunkett W. Homoharringtonine reduced Mcl-1 expression and induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2011. Jan 6; 117(1): 156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 1984; 22: 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res 2010. Jan 15; 70(2): 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen CB, Ballut L, Johansen JS, Chamieh H, Nielsen KH, Oliveira CL, et al. Structure of the exon junction core complex with a trapped DEAD-box ATPase bound to RNA. Science 2006. Sep 29; 313(5795): 1968–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwatani-Yoshihara M, Ito M, Ishibashi Y, Oki H, Tanaka T, Morishita D, et al. Discovery and Characterization of a Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4A-3-Selective Inhibitor That Suppresses Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay. ACS Chem Biol 2017. Jul 21; 12(7): 1760–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blagosklonny MV, Alvarez M, Fojo A, Neckers LM. bcl-2 protein downregulation is not required for differentiation of multidrug resistant HL60 leukemia cells. Leuk Res 1996. Feb; 20(2): 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konopleva M, Contractor R, Tsao T, Samudio I, Ruvolo PP, Kitada S, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis sensitivity and resistance to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2006. Nov; 10(5): 375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yecies D, Carlson NE, Deng J, Letai A. Acquired resistance to ABT-737 in lymphoma cells that up-regulate MCL-1 and BFL-1. Blood 2010. Apr 22; 115(16): 3304–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bojarczuk K, Sasi BK, Gobessi S, Innocenti I, Pozzato G, Laurenti L, et al. BCR signaling inhibitors differ in their ability to overcome Mcl-1-mediated resistance of CLL B cells to ABT-199. Blood 2016. Jun 23; 127(25): 3192–3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di L, Umland JP, Trapa PE, Maurer TS. Impact of recovery on fraction unbound using equilibrium dialysis. J Pharm Sci 2012. Mar; 101(3): 1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowley M, Kulagowski JJ, Watt AP, Rathbone D, Stevenson GI, Carling RW, et al. Effect of plasma protein binding on in vivo activity and brain penetration of glycine/NMDA receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 1997. Dec 5; 40(25): 4053–4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lázníček M, Lázníčková A. The effect of lipophilicity on the protein binding and blood cell uptake of some acidic drugs. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 1995 1995/June/01; 13(7): 823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DA, Di L, Kerns EH. The effect of plasma protein binding on in vivo efficacy: misconceptions in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9(12): 929–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan CC, Dostie J, Diem MD, Feng W, Mann M, Rappsilber J, et al. eIF4A3 is a novel component of the exon junction complex. RNA 2004. Feb; 10(2): 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matthews JH. The Molecular Pharmacology of Pateamine A. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/1883/thesis.pdf?sequence=1, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meng H, Li C, Wang Y, Chen G. Molecular dynamics simulation of the allosteric regulation of eIF4A protein from the open to closed state, induced by ATP and RNA substrates. PLoS One 2014; 9(1): e86104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubio CA, Weisburd B, Holderfield M, Arias C, Fang E, DeRisi JL, et al. Transcriptome-wide characterization of the eIF4A signature highlights plasticity in translation regulation. Genome Biol 2014; 15(10): 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolfe AL, Singh K, Zhong Y, Drewe P, Rajasekhar VK, Sanghvi VR, et al. RNA G-quadruplexes cause eIF4A-dependent oncogene translation in cancer. Nature 2014. Sep 4; 513(7516): 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lam LT, Pickeral OK, Peng AC, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Giltnane JM, et al. Genomic-scale measurement of mRNA turnover and the mechanisms of action of the anti-cancer drug flavopiridol. Genome Biol 2001; 2(10): RESEARCH0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozopas KM, Yang T, Buchan HL, Zhou P, Craig RW. MCL1, a gene expressed in programmed myeloid cell differentiation, has sequence similarity to BCL2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1993. Apr 15; 90(8): 3516–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers S, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science 1986. Oct 17; 234(4774): 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jain N, Thompson PA, Ferrajoli A, Burger JA, Borthakur G, Takahashi K, et al. Combined Venetoclax and Ibrutinib for Patients with Previously Untreated High-Risk CLL, and Relapsed/Refractory CLL: A Phase II Trial. Blood 2017; 130(Suppl 1): 429–429. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cervantes-Gomez F, Lamothe B, Woyach JA, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Balakrishnan K, et al. Pharmacological and Protein Profiling Suggests Venetoclax (ABT-199) as Optimal Partner with Ibrutinib in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2015. Aug 15; 21(16): 3705–3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Modi P, Balakrishnan K, Yang Q, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Gandhi V. Idelalisib and bendamustine combination is synergistic and increases DNA damage response in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Oncotarget 2017. Mar 7; 8(10): 16259–16274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.