Abstract

Background: The disproportionately high prevalence of poor reproductive and sexual health outcomes among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women is related to histories of colonization, oppression, and structural racism. Intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence (SV) contribute to these health outcomes.

Materials and Methods: Narrative interviews were conducted with AI/AN women from four tribal reservation communities. Interviews explored connections among sexual and reproductive health, IPV, SV, reproductive coercion (RC), and pregnancy experiences as well as women's experiences of healing and recovery.

Results: Among the 56 women interviewed (aged 17–55 years, 77% were aged 40 years and younger), all described multiple exposures to violence and highlighted lack of disclosure related to sexuality, childhood abuse, SV, and historical trauma. Access to confidential reproductive health services and contraceptive education was limited. Almost half (45%) reported experiencing RC in their lifetime. Use of substances occurred in both the context of SV and for surviving after exposure to violence. Women underscored the extent to which IPV, SV, and RC are embedded in histories of colonization, racism, and ongoing oppression. Interventions that incorporate AI/AN traditions, access to culturally responsive reproductive health and advocacy services, organizations, and services that have AI/AN personnel supporting survivors, public discussion about racism, abuse, sexuality, and more accountable community responses to violence (including law enforcement) are promising pathways to healing and recovery.

Conclusions: Findings may advance understanding of AI/AN women's reproductive health in the context of historical trauma and oppression. Intervention strategies that enhance resiliency of AI/AN women may promote reproductive health.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, sexual violence, pregnancy, reproductive coercion, American Indian and Alaska Native persons (AI/AN), qualitative research

Introduction

Poor reproductive and sexual health outcomes among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women, including unintended pregnancy, are related to histories of colonization, oppression, and structural racism.1–3 Intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence (SV) increase risk for poor reproductive health. Fear of consequences for refusing sex and abusive partners' influence on sexual decision-making are well-recognized pathways for increasing women's risk for unintended pregnancy.4–13 Contraceptive discrepancy (i.e., using a different method than preferred),14 inconsistent and nonuse of condoms,13,15,16 and fear of condom negotiation15,17 are common among women who have experienced abuse. Interference with contraception18,19 and drug/alcohol involvement20 also link abuse with unintended pregnancy,18,19 compounded by limited access to emergency contraception and abortion especially among AI/AN women.21

IPV has also been linked to unintended pregnancy via reproductive coercion (RC). Abusive male partners attempt to impregnate female partners by pressuring them to become pregnant, manipulating condoms, threatening violence in response to condom requests, and contraceptive sabotage.7,22–25 Studies have documented high rates of IPV/SV and unintended pregnancy in AI/AN communities,2,26,27 yet the role of RC in this population has not been explored. Studies on RC to date have not included sufficient numbers of AI/AN women to understand how IPV, RC, pregnancy intentions, and contraceptive behaviors may be similar or different from non-AI/AN women. In addition, studies have paid limited attention to cultural resiliency and traditional healing that could provide protective strategies to buffer communities experiencing high levels of trauma and low access to resources.28,29

Research on resiliency has yet to examine ways in which communities and individuals use strengths and assets to cope with unrelenting adversities in the context of AI/AN women's reproductive decision-making. This in-depth qualitative study explored how exposure to IPV/SV and RC may influence pregnancy intentions and contraceptive behaviors within AI/AN communities.

The study aimed to elucidate how AI/AN women who have experienced IPV/SV describe pregnancy experiences, contraceptive behaviors, and reproductive decision-making in relation to violence. Given the inextricable historical, cultural, and structural influences on AI/AN women's experiences of violence, a multilayered qualitative analysis was applied. This approach was used to facilitate understanding of individual-level factors and sociocultural and historical forces as they pertain to AI/AN women's reproductive autonomy and safety from violence-related experiences. Input from tribal community members further elucidated community assets that could be mobilized to reduce women's risk for IPV/SV, RC, and unintended pregnancy and integrated into a conceptual model to guide culturally responsive violence prevention and health promotion efforts.

Materials and Methods

An AI/AN advocate (E.G.) and AI/AN researcher (K.J.E.S.) reviewed study design and protocols to ensure cultural appropriateness. Four AI/AN communities (two Northwestern, one Midwestern, and one Northeastern) agreed to participate in the study. All communities were federally recognized tribes on small reservations situated near small towns and/or cities. Sites had an existing relationship with an SV prevention advocate (E.G.) through prior participation in federally funded public health initiatives related to IPV/SV. Each site had experience with training community members and agencies in confidentiality, health effects of IPV/SV, effects of historical trauma on individuals and community, and client-centered safety responses. Within each site, a local AI/AN advocate assisted with identifying women to participate and serve as a liaison among women and study personnel. Tribal leadership (e.g., tribal council, board members) and community members at each site were informed in 1- to 2-hour formal meetings with research team leads (E.G. and E.M.) and the local AI/AN advocate about the proposed research. They had the opportunity to ask questions and provide feedback before deciding whether to become partners.

Tribal leadership from all four sites approved conduct of the study via tribal processes. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board also approved the study. The research team adhered to Native research ethics of respect, continual dialogue, building on strengths in following tribal protocols, maintaining open communication, having avenues for feedback, input and questions from tribal community members and leadership, and re-evaluating all stages of research to ensure positive impact for Native communities.30 Advocates were available to provide ongoing support to participants. One of the investigators (E.G.), an AI/AN advocate with 32 years of experience, provided consultation and support for advocates and participants.

We obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality to protect research data from subpoena. The research team never had access to the full name of any participant; no names were ever connected to data. Due to child abuse reporting requirements and risk for breach of confidentiality associated with interviewing minors, this study focused on women aged 18 years and older.

Each site's tribal advocate identified a private space to ensure that women could engage without being identified as study participants. The study focused on women aged 18–50 years (with an emphasis on 18–35 years, i.e., childbearing age), and advocates assisted with recruitment, including inviting individuals for whom they had previously provided services. Women were told that the interview would be about their relationships and health. Flyers about the study were posted at each community's health center and common spots (e.g., grocery stores, casinos, community centers) with the local advocate's contact information. Only the advocate had contact information for participants, which was never disclosed to the research team.

When interested participants arrived for the interview, we used a private space to explain the study, including the focus on IPV/SV and RC, and allowed individuals to decline participation. Women were asked to first complete a survey on a computer (with option of audio-recorded questions read to them through headphones), which asked about relationship violence, pregnancy experiences, and demographic characteristics (Supplementary Table S1). We noted that the survey included questions about violence that might be difficult and they could stop the survey at any time. After the survey, we confirmed that they still were willing to move forward with the interview. The interview lasted 60–120 minutes using an interview guide developed with the research team and tribal advocates to ensure that cultural norms were respected. We stopped a few times throughout the interview to check in with each participant about how they were feeling. No one declined participation, and all completed both survey and interview.

Interviews began with women drawing their life history timeline, marking events including relationships and pregnancies. They then talked about these life events and relationships in whatever order they chose. Interviewers explored experiences with health care, other professionals (such as law enforcement, teachers, judicial system), use of services, community responses, and ideas for improving community response to IPV/SV as well as women's health. Interviews probed for strategies that women used to increase safety, heal from experiences of violence, and promote their health and well-being. Following the interview, women received information about local and national advocates, resources, and a $50 gift card.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed into written format; audio files were destroyed after transcripts were checked for accuracy and identifiable information removed. Using a consensus coding approach (supported with Atlas.ti coding software), two non-AI/AN coders independently coded the first five transcripts and then compared and adjusted codes. The team created a codebook with definitions, rules, and examples for each code. Key a priori topics of interest were pregnancy history, IPV/SV/RC, health impact, health care response, and suggestions regarding what would have been helpful for women, with additional codes identified during review of each transcript. Revisions to the codebook were made iteratively. Two coders coded each transcript using the final codebook. Coded transcripts were compared, and disagreements resolved by the senior investigator (E.M.).

In a process called axial coding, codes were combined into broader categories to define emerging patterns or themes and capture heterogeneity of experiences. For this analysis, we focused on the ways in which women described how IPV/SV and RC have intersected with their sexual and reproductive histories. We identified ways in which women described overcoming adversities as well as ideas for what would have helped them. We included care-seeking experiences and identified contextual barriers and facilitators of contraceptive use as well as access to IPV/SV services.

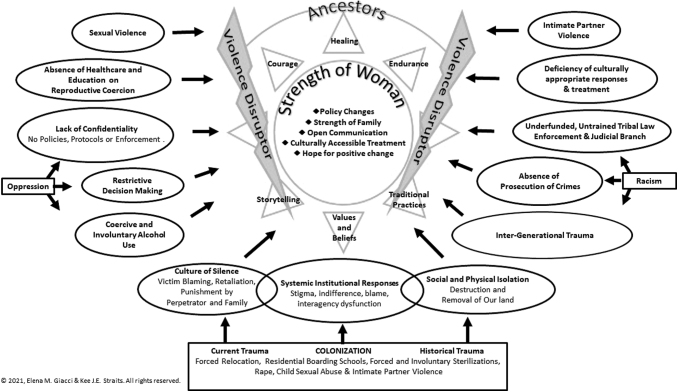

Interviews explored individual factors and experiences impacting sexual and reproductive health and did not specifically ask about systemic, cultural, or sociopolitical factors. Some responses were frequent enough to suggest broader sociopolitical influences. The themes were reviewed by a team of AI/AN experts and tribal partners involved in this study. The two lead investigators (E.G. and E.M.) returned to each site to review study findings with tribal partners, community members, and health professionals and discuss development of culturally responsive interventions based on findings. Two AI/AN team members (E.G. and K.J.E.S.) analyzed findings from the interviews and summarized responses that were connected to sociopolitical factors and potential community-level solutions, and created a conceptual map from the findings (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Violence Disruptor Model—an American Indian/Alaska Native Community-informed framework for ending violence.

Results

Respecting the wishes of the AI/AN partners who requested that we not take women's voices out of context, we do not provide actual quotes in this article. As many women were recruited by advocates providing IPV/SV services, almost all participants reported experiencing violence at the hands of a partner (96%). Almost half (45%) reported RC with 14% reporting this in the past 3 months. Of the 56 women, 95% had been pregnant, and 57% of them reported unexpected (mistimed or unintended) pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 56)

| Characteristic | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 17–25 | 27 (15) |

| 26–30 | 21 (12) |

| 31–40 | 39 (22) |

| 41–55 | 13 (7) |

| Lifetime history | |

| Ever pregnant | 95 (53) |

| Unintended pregnancya | 57 (30) |

| IPV (physical or sexual violence) victimization | 96 (54) |

| Physical IPV (hit, kicked, slapped, choked, physically hurt) | 89 (50) |

| Sexual IPV (made to have sex with or without use of force and threats) | 79 (44) |

| Reproductive coercion | 45 (25) |

| Conflict over pregnancy outcomes | 43 (24) |

| Recent (past 3 months) experiences | |

| Physical and sexual IPV | 21 (12) |

| Reproductive coercion | 14 (8) |

| Sex without condom when wanted to use one | 16 (9) |

| Fear of asking partner to use condom or discussing birth control, or fear of refusing sex | 13 (7) |

Denominator restricted to those who have ever been pregnant (n = 53).

IPV, intimate partner violence.

Below, we summarize key themes emerging from the interviews. Table 2 summarizes the contextual analysis that emerged with tribal partners as interview findings were reviewed with each site. Table 3 highlights protective factors and individual and community strengths. A conceptual framework integrates interview findings and tribal partner feedback with existing literature into broader sociopolitical and historical context (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Contextual Factors Connected to Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, and Reproductive Coercion, and Reproductive/Sexual Health as Identified by Participants, Advocates, and Tribal Partners

| Category | Themes |

|---|---|

| Historical, current trauma, and racism sociopolitical factors | • Intergenerational trauma produced by forced relocation, destruction of land resources, and systemic oppression • Specific histories of residential school system, removal of babies from tribal families, and forced sterilization of AI/AN women • Generational trauma that prohibited disclosure and restrictive decision-making for victims • “Culture of Silence” of survivor; keeping stories of abuse secret • Racism, oppression, and microaggressions reflected in law enforcement agencies and health center responses • Systemic and institutional responses (e.g., law enforcement) of stigma, indifference, blame, and actively creating barriers • Absence of prosecutions of rape, child sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence • Inadequate judicial education and understanding of sexual and domestic violence in AI/AN communities • Lack of culturally appropriate responses for AI/AN survivors of sexual assault • Historical mistrust of health, social services, and outside non-Native community resources |

| Specific history of residential boarding schools | • Continued acts of sexual abuse against children at residential schools • Physical, emotional, and psychological abuse enacted against AI/AN children |

| Environmental/social context | • Coercive and forced alcohol and drug-facilitated sexual assault preceding sex and/or unintended pregnancy (either intentionally by subject as negative coping tool or by perpetrator to coerce/control victim) • Absence of health care and education services that provide reproductive health needs and sexual education • Transportation barriers to accessing and receiving rape crisis services and reproductive/sexual health services • Cultural taboos to discussion of sex |

| Impairing decision-making | • Partner determines contraceptive decisions • Forced sex or intentional actions by partner (including using alcohol and other drugs as a date rape drug) to impair and diminish decision-making and increasing condom misuse |

| Social consequences/community responses | • Deficiency of culturally appropriate services and treatment • Lack of confidentiality and policy/protocols that enforce them • Continued social isolation and blaming for IPV/SV and reproductive coercion • Retaliation and isolation by perpetrator's family • Loss of access to community supports • Lack of prosecution of violent crimes on tribal land • Underfunded, inadequate training, response, or resources from tribal and outside law enforcement on IPV/SV |

| Intergenerational trauma | • Childhood abuse among multiple generations within family • Generational trauma that prohibited disclosure by victim (e.g., disbelief, active silencing, no responsiveness) |

AI/AN, American Indian and Alaska Native; IPV, intimate partner violence; SV, sexual violence.

Table 3.

Resilience Factors for Surviving Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, and Reproductive Coercion as Identified by Participants, Advocates, and Tribal Partners

| Category | Themes |

|---|---|

| Individual characteristics, situations, and strengths | • Family—including mother or other female adult caregiver supporting and protecting family • Continued hope for a better future for their children and community |

| Cultural identity, connection, and participation | • Not feeling whole without our connection to AI/AN culture • Healing found specifically in finding courage, strength, and endurance in culture and community • Developing a renewed stronger AI/AN identity • Improved cultural connection strengthening social supports, healing, traditional practice, and spirituality |

| Values/beliefs | • Support changing personal and community beliefs around sexual violence and silence • Acknowledging victims are not to blame • Recognize one's strengths, beliefs, and values and of other women and how community can change acceptance of violence as norm |

| Personal and community shifts in communication about sex, sexuality, and abuse | • Open communication with adults about healthy sexuality, relationships, and body image • Open communication with own children about sexuality, relationships, and body image • Hope for changing culture of silence around abuse • Sharing how to access support • Culturally appropriate educational materials about sexuality with discussion of abuse |

| Culturally accessible treatment services | • Services or treatment accessible on or near home reservation • Services provided by AI/AN advocates, or with other AI/AN women • Services that integrate traditional AI/AN concepts and traditions supported by community • Having culturally appropriate educational materials • Creating confidential and culturally relevant spaces for women to share their stories • Non-Native organizations having AI/AN advocacy representation |

| Placing IPV/SV in context of historical trauma | • Connecting historical trauma and silence to boarding school abuse • Educating individuals and community on intergenerational trauma of family members to remove blame, shame, and guilt • Support of development of cultural healing practices that include survivor journey |

AI/AN, American Indian and Alaska Native; IPV, intimate partner violence; SV, sexual violence.

Limited sexual health education and access to reliable health services and information

A common theme was lack of conversation around sexuality, healthy sexual development, and reproduction. Most women reported complete silence within their families, with shame and guilt associated with discussion of these topics. One woman described that whenever a sexual encounter was on television, she and her siblings were sent out of the room. She added that her mother never discussed sex with her. Another young woman shared that when she got her period, her mother expressed exasperation about having to address this with her. When asked about whether their mothers spoke with them about sex, women consistently stated that it was left up to schools. Yet sex education through schools was minimal with 1 or 2 hours of classes in high school on biology and condoms with no discussion of other contraception, consent, relationship abuse, or communication. Limited understanding of how one got pregnant contributed to unexpected pregnancy.

Women were reticent to go to the doctor to learn about contraception, as this was rarely encouraged by their mothers. Among women who did seek care, health care providers rarely discussed contraception. Concerns about confidentiality when seeking care were common, including being seen at the only pharmacy in the community.

A source of (mis)information about sex and contraception came from men with whom the women were having sex. Women's lack of information translated to not being informed that they even had a choice about contraceptive decisions in their sexual relationship, increasing opportunities for coercion and unplanned pregnancies. One young woman, describing her first pregnancy, explained that she trusted her partner to prevent pregnancy because he seemed to know more about menstrual cycles than she did; looking back, she realized the pregnancy (which she neither desired nor planned) was likely his plan.

RC and contraception

RC emerged in many stories. About half of the women described male partners trying to impregnate them on purpose, refusing to use condoms and tampering with contraceptive methods. As noted above, contraceptive decision-making was influenced by women's incomplete knowledge of reproductive health. Women attributed RC to community norms limiting education about sexuality, hindering disclosure of SV in their families and communities, including lack of awareness of RC as an aspect of abuse.

Early experiences of violence and sexual abuse figured prominently in women's experiences. Women pointed to alcohol and other date rape drugs used by perpetrators to commit forced sex. Some women described being told by family or community members that they were lying about such experiences, which led them to not seek care and to use substances to cope. Women noted failure of law enforcement (on and off reservation) and U.S. Attorney's Office to respond to such violence, especially when alcohol and drugs were involved. Perceived community expectations around encouraging pregnancy (often with prohibitions against abortion) combined with lack of local response to IPV/SV (including childhood abuse) contributed to shifting the locus of control for pregnancy and sexual decision-making away from women. Women, however, expressed hope for changing the culture surrounding relationship violence and sexuality in their communities, and increasing women's reproductive autonomy (Table 3).

Substance use as context for sexual activity in adolescence

Many described growing up surrounded by drugs and alcohol. Some women described gathering with peers to drink or get high starting in early adolescence. Date rape drugs including alcohol were interwoven with women's descriptions of impaired sexual decision-making and lack of knowledge around sex and contraception. Women noted alcohol and drugs as prerequisites to sex during this time of their lives. Some connected this to abuse in childhood and using substances for coping; others described being forced to use drugs or alcohol by their abusers. One woman explained that she used drugs during sexual encounters to numb the pain she felt as a result of previous abuse. Others stated drinking or drugs could lower inhibitions and allow them to have sex with less trauma.

Several women noted their first unintended pregnancy (usually in adolescence) occurred while being coerced into using drugs or alcohol. The majority described experiences during adolescence of agreeing to have sex when they did not want to have it, and fearing anger from their partner if they disagreed. One woman described how a trusted male friend got her drunk then forced her to have sex for the first time while she was unaware of what was happening. None of the participants used the term “rape” to describe these encounters. Following such experiences of violence in adolescence, women described self-medicating with drugs and alcohol, which in turn led to more experiences of IPV/SV and pregnancies.

Law enforcement and other social service agency responses

Women underscored how racism, limited responsiveness, or indifference to the violence from local agencies contributed to their isolation. The majority of women shared that when they contacted tribal police or authority, no action was taken or any resolution achieved. Many reported feeling unsafe, not taken seriously, or even ridiculed. Women perceived that law enforcement (tribal, state, or federal) was on the side of the perpetrator. Some women reported reaching out to other services for help with minimal results. One voiced that a local non-AI/AN domestic violence agency worker seemed inconvenienced by having to help her, making the participant feel like reporting the incident was not worth it.

Health care system responses

Local health care services were seen as unhelpful, and women overwhelmingly shared concerns around confidentiality. One participant shared that within 5 minutes of leaving a clinic appointment during which she found out she was pregnant, she started receiving phone calls from acquaintances who heard the news from a clinic nurse. Women reported being asked about IPV only during a pregnancy by their gynecologist, not other health care providers. Mental health services were difficult to receive, as in the case of a woman who was denied a prescription for an antidepressant because the provider did not want to prescribe medicine for domestic issues. Women also described distrust for health and social services, preventing them from seeking help.

Community supports and resiliency

All participants noted finding strength in their culture and traditions during their healing process, often saying they felt that they had lost that part of themselves and needed to find a way back to AI/AN culture to feel whole (Table 3). Many women shared how AI/AN advocacy services and trauma recovery centers provided support. Most interviews referenced the AI/AN advocate within their community as a vital source of support. As women recovered from trauma and substance use, new messages from these AI/AN programs replaced negative messages reinforcing silence that women had learned in childhood. Lessons incorporated traditional AI/AN concepts of the strength of women in their community, reminded them of their own cultural roots, and the courage of their feminine ancestors.

Personal resilience

Women all described ways to reconcile their experiences in the context of community historical trauma (Table 3). They recounted what they had learned of their parents' and grandparents' histories of trauma, how relatives were exposed to violence, at home or in state-sponsored boarding schools, and how those experiences could lead to normalizing violence within their homes. Several participants offered explanations for the abuse they had experienced as children that parents were trying to do their best using what they were taught.

With acknowledging historical and ongoing trauma on families and communities, women were asked at the end of the interview what messages they wanted to pass on to their children or the younger generation. Women spoke about strengths, connectedness, and changing the culture surrounding abuse as well as silences related to sexuality. One woman explained that she tells her children to appreciate the sacredness of their bodies and disclose if anyone violates them. All spoke about the messages they are passing on to the next generation: communicating openly with their own children about their sexuality, healthy relationships, and supports available if something happens to them.

Violence Disruptor Model: interpretation of findings

The Violence Disruptor Model (Fig. 1) is a conceptual map for understanding individual and systemic barriers to treatment and resiliencies for AI/AN women who have experienced IPV/SV. As Indigenous women, the two lead authors describe the creation of this model in their own words:

“The Violence Disruptor Model addresses the fundamental principles of sexual and intimate partner violence in AI/AN communities. The model arose after careful reflection, review of themes encountered in the interviews, and tribal member feedback. The women's life stories provided clear links to systemic, historical, and sociopolitical realities that the health literature too often fails to connect to Native women's lived experiences of IPV/SV. To fathom the epidemic of IPV/SV in American Indian Country, it is paramount to acknowledge the inequities, racism, and historical trauma which exist as direct consequences of colonization. These attacks on AI/AN communities have been incessant from the moment colonizers stepped on our land. The model visualizes the complexities and frames these inequities as consequences of oppression created explicitly against AI/AN people that violates our ancestors' traditional values and beliefs. Summarizing only the trauma and barriers in the women's stories would lead to further stigma, disparities, and inequity. This model highlights individual, family, and community strengths described by these women as sources of their survivance in overcoming experiences of IPV/SV.”

Discussion

These interviews with AI/AN women and tribal member interpretations, taken together, underscore the extent to which IPV, SV, and RC are deeply embedded in histories of colonization, racism, and ongoing oppression. Research suggests that sexual assault against AI/AN women was used as a deliberate tool for colonization and cultural genocide18,31,32 with present-day systemic effects such as federal limitations on tribal responses to rape continuing to limit community responses to such violence.33,34 The many barriers to reporting IPV/SV in AI/AN communities likely perpetuate such violence.8,14,17,35–39 Although not in the interview guide specifically, all participants reflected on sociocultural factors in AI/AN communities that contribute to unplanned pregnancies and ongoing exposure to IPV/SV. Participants underscored the sacredness of stories of survival, adding deeper understanding of the resilience and strength of AI/AN women.

Recurring theme of silences and secrecy were described in the context of racism, historical, current, and intergenerational trauma. Women's reproductive experiences were shaped by silencing and shame regarding violent experiences, which they linked to histories of marginalization of their communities. Specifically, women described inadequate and limited access to sexual health education and services. This, combined with negative family and community responses to abuse, led to lack of care seeking for reproductive health needs. Inequitable access to confidential health services and ineffective service agency responses (including law enforcement) reflect ongoing neglect of AI/AN communities. Legal and judicial responses, in turn, are complicated by pervasive challenges of placing blame on female victims while tribal, state, and federal lack of collaboration perpetuate the epidemic of “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.”40,41

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore RC among AI/AN women. Few studies have directly examined reasons for the disproportionately high rates of unintended pregnancy among AI/AN women.42,43 Most research related to unintended pregnancy in AI/AN communities has focused on adolescent pregnancy and sexual risk among youth.35,44 Similar to non-AI/AN women, RC occurred in the context of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse by partners who also interfered with contraceptive use and care seeking.16,24,45 Some women perceived that their partners were actively trying to impregnate them against their wishes, and described partner and community influences on keeping pregnancies they did not want.

Substance use and exposure to violence including sexual abuse have been linked to sexual risk among AI/AN youth,46–48 a connection reflected in many stories. Participants described using substances for self-medication following violence exposure and intentional drug and alcohol use by perpetrators to control them. Contraceptive and condom nonuse—both intentional and not—in the setting of alcohol and other drugs compounded risk for unplanned pregnancy. Prevalence of drugs and alcohol in tribal communities is connected to colonization and structural racism.49,50 Consistent with prior study,51 participants underscored the ubiquity and devastating consequences of substances in tribal communities as a reflection of historical oppression and communal sorrow.

Women and tribal members reflected on how threats of physical/cultural extermination of an entire group of people (both historical and ongoing) changes communal motivations around reproduction and the ways that individual AI/AN women and tribal communities continue to struggle with having jurisdiction over their own bodies and land. Secrecy enforced by oppressors permeates these stories. As noted by AI/AN scholars, it is possible that such silences around abuse and sexuality were not a cultural norm before colonization. Instead, they may be both a reflection of Christian missionizing (sexuality as taboo; abuses perpetrated by officiates of the Church) and a response to surviving SV perpetrated on AI/AN women through brutal acts of colonization (e.g., raids, rape, massacre), and state sponsored violence (e.g., forced removals of children from families, boarding schools, and forced sterilization).1 While mechanisms connecting IPV/SV to unintended pregnancy have been described for non-AI/AN women, these interviews highlight how sociocultural factors unique to AI/AN communities constrain women's reproductive decision-making. These are illustrated in the Violence Disruptor Model.

In describing pathways to healing, women pointed to potential interventions to address historical and current trauma including: childhood sexual abuse prevention; strengthening tribal policies and practices that raise community awareness and end silence around abuse and sexuality; comprehensive sexuality education, including healthy relationships and consent; culturally appropriate IPV/SV services; confidential reproductive health services; and responsive and supportive law enforcement offices. The potential for mobilizing community strengths to end violence is summarized in the Violence Disruptor Model that emerged from this work.

Sociocultural strengths revealed in the interviews and subsequent discussions with tribal leaders are highlighted in this conceptual model. Connection to the reservation and one's tribe and AI/AN identity promoted resiliency by guiding healing and recovery. Women who connected with AI/AN advocates and shared their stories with other AI/AN women described how this relieved the burden of holding so many secrets. Creating spaces for women to share stories and reduce isolation and shame may help nurture women's sense of control over their sexual and reproductive lives. Increasing capacity within AI/AN communities to have a robust support system for IPV/SV survivors is critical for developing a culturally responsive foundation for women's health. As noted in the Violence Disruptor Model, targets for intervention could include education on historical and current trauma effects on IPV/SV, use of traditional values as a protective healing strategy, distinguishing between norms that became instituted within AI/AN communities after colonization (secrecy and silence) and comparing systemic abuse vs. healthy traditional values. Interventions to reduce RC and increase reproductive autonomy and safety from IPV/SV for AI/AN women may benefit from research that explores resilience and traditional healing, which can be combined with harm reduction and protective policies.

As a qualitative exploratory study, this study has limitations. As with most qualitative studies, the sample size was small. Content saturation was reached after one third of interviews were completed, suggesting shared experiences across these tribal communities. We continued interviews to ensure heterogeneity of experiences by age, use of services, and pregnancy history. The study was not designed to examine differences across communities and centered universal themes of trauma reflected in the stories. Although we explored strengths and community resiliency, the interview guide emphasized individual experiences. Future studies could further elaborate on resilience in the context of sociocultural influences. Non-AI/AN researchers did the first round of coding and may have introduced information bias. Tribal members and the lead authors (both AI/AN) offered more nuanced interpretation. Finally, as interviews preferentially included women with histories of IPV/SV, the stories may not reflect experiences of women who had unplanned pregnancies and no exposure to IPV/SV.

Conclusions

This study explored connections among IPV, SV, RC, and pregnancy among AI/AN women, embedded in histories of colonization, racism, and oppression. Women and tribal partners provided a road map for culturally responsive interventions that address exposure to IPV/SV and promote reproductive health. As the COVID-19 pandemic now ravages AI/AN communities, findings may guide development of culturally resonant responses to IPV/SV that integrate community resiliency and address historical trauma and systemic barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the women, advocates, tribal leaders, and community members who made this participatory project possible. We also thank members of Dr. Miller's research team who participated in data analysis including Theresa Gmelin.

Authors' Contributions

E.G. and E.M. conceived the study, applied for funding, conducted the study, participated in data analysis, and all stages of article preparation. K.J.E.S. participated in data analysis and interpretation as well as writing, review, and revisions of drafts of the article. A.G., S.M-.W., and R.I. participated in literature review, data analysis, and review of drafts of the article. E.G. and K.J.E.S. created the Violence Disruptor Model.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Miller receives royalties from UpToDate, a clinical decision support resource for clinicians.

Funding Information

This project was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (Grant No. NICHD R21HD077101 to E.M.). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Urban Indian Health Institute. Reproductive health of Urban American Indian and Alaska Native women: Examining unintended pregnancy, contraception, sexual history and behavior, and non-voluntary sexual intercourse, Seattle, WA: Urban Indian Health Institute, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bohn DK. Lifetime and current abuse, pregnancy risks, and outcomes among Native American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2002;13:184–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palmer JE, Chino M. Interpersonal violence and American Indian and Alaska Native communities. In: Cuevas CA, Rennison CM, eds. The Wiley handbook on the psychology of violence. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016:678–694. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pallitto CC, O'Campo P. The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: Analysis of a national sample from Colombia. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2004;30:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hathaway JE, Mucci LA, Silverman JG, Brooks DR, Mathews R, Pavlos CA. Health status and health care use of Massachusetts women reporting partner abuse. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao W, Paterson J, Carter S, Iusitini L. Intimate partner violence and unplanned pregnancy in the Pacific Islands Families Study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007;100:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lang DL, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I. Associations between recent gender-based violence and pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, condom use practices, and negotiation of sexual practices among HIV-positive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG 2007;114:1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Perales MT, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;100:104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK. Domestic violence, contraceptive use, and unwanted pregnancy in rural India. Stud Fam Plann 2008;39:177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coker AL, Derrick C, Lumpkin JL, Aldrich TE, Oldendick R. Help-seeking for intimate partner violence and forced sex in South Carolina. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Violence and reproductive health: Current knowledge and future research directions. Matern Child Health J 2000;4:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Decker MR, Raj A, Silverman JG. Sexual violence against adolescent girls: Influences of immigration and acculturation. Violence Against Women 2007;13:498–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams CM, Larsen U, McCloskey LA. Intimate partner violence and women's contraceptive use. Violence Against Women 2008;14:1382–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sales JM, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Rose E, Crosby RA. The mediating role of partner communication skills on HIV/STD-associated risk behaviors in young African American females with a history of sexual violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silverman JG, McCauley HL, Decker MR, Miller E, Reed E, Raj A. Coercive forms of sexual risk and associated violence perpetrated by male partners of female adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2011;43:60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1016–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McFarlane J, Malecha A, Watson K, et al. Intimate partner sexual assault against women: Frequency, health consequences, and treatment outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fantasia HC, Sutherland MA, Fontenot HB, Lee-St John TJ. Chronicity of partner violence, contraceptive patterns and pregnancy risk. Contraception 2012;86:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sapra KJ, Jubinski SM, Tanaka MF, Gershon RR. Family and partner interpersonal violence among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Inj Epidemiol 2014;1:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gattozzi E, Asetoyer C. Indigenous Women's Reproductive Justice: A survey of the availability of plan B® and emergency contraceptives within Indian Health Service. 2008. Lake Andes, SD: Native American Women's Health Education Resource Center. Available at: http://www.nativeshop.org/images/stories/media/pdfs/SurveyofEC_PlanBintheIHSER2008.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2021.

- 22. Center for Impact Research. Domestic violence and birth control sabotage: A report from the Teen Parent Project. Chicago, IL: Center for Impact Research, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller E, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway JE, Silverman JG. Male pregnancy promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: Findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr 2007;7:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception 2010;81:316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schultz K, Walls M, Grana SJ. Intimate partner violence and health: The roles of social support and communal mastery in five American Indian communities. J Interpers Violence 2021;36:NP6725–NP6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans-Campbell T, Lindhorst T, Huang B, Walters KL. Interpersonal violence in the lives of urban American Indian and Alaska Native women: Implications for health, mental health, and help-seeking. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1416–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davis RE. The strongest women”: Exploration of the inner resources of abused women. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1248–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women taking action and generating evidence, World Health Organization, 2010. Available at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/9789241564007_eng.pdf

- 30. Straits KJE, Bird DM, Tsinajinnie E, et al. Guiding principles for engaging in research with Native American communities, version 1. UNM Center for Rural and Community Behavioral Health & Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Willmon-Haque S, BigFoot SD. Violence and the effects of trauma on American Indian and Alaska native populations. J Emot Abuse 2008;8:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith A. Conquest: Sexual violence and American Indian genocide, Reprint, Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meyer-Emerick N. The Violence against Women Act of 1994: An analysis of intent and perception. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Washburn KK. Testimony before the U.S. sentencing commission on the tribal law and order act. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1539721 or 10.2139/ssrn.1539721 Accessed January 20, 2010. [DOI]

- 35. Palacios JF, Strickland CJ, Chesla CA, Kennedy HP, Portillo CJ. Weaving dreamcatchers: Mothering among American Indian women who were teen mothers. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dalla RL, Marchetti AM, Sechrest EBA, White JL. All the men here have the Peter Pan syndrome—they don't want to grow up’: Navajo adolescent mothers” intimate partner relationships—a 15-year perspective. Violence Against Women 2010;16:743–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Finfgeld-Connett D. Qualitative systematic review of intimate partner violence among Native Americans. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2015;36:754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hamby S. The path of helpseeking: Perceptions of law enforcement among American Indian victims of sexual assault. J Prev Interv Community 2008;36:89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wahab S, Olson L. Intimate partner violence and sexual assault in Native American communities. Trauma Violence Abuse 2004;5:353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Missing and murdered: Act now for comprehensive protection of indigenous women and girls. Available at: https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/484201-missing-and-murdered-act-now-for-comprehensive-protection-of Accessed December 30, 2020.

- 41. Ross R, GreyWolf I, Tehee M, Henry S, Cheromiah M. Missing and murdered indigenous women and children. Open Science Framework, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soon R, Elia J, Beckwith N, Kaneshiro B, Dye T. Unintended pregnancy in the native Hawaiian community: Key informants' perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2015;47:163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stockman JK, Hayashi H, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:62–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rutman S, Park A, Castor M, Taualii M, Forquera R. Urban American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Youth risk behavior survey 1997–2003. Matern Child Health J 2008;12 Suppl 1:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Torpy SJ. Native American women and coerced sterilization: On the trail of tears in the 1970s. Am Indian Cult Res J 2000;24:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hellerstedt WL, Peterson-Hickey M, Rhodes KL, Garwick A. Environmental, social, and personal correlates of having ever had sexual intercourse among American Indian youths. Am J Public Health 2006;96:2228–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Devries KM, Free CJ, Morison L, Saewyc E. Factors associated with the sexual behavior of Canadian Aboriginal young people and their implications for health promotion. Am J Public Health 2009;99:855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kaufman CE, Desserich J, Big Crow CK, Holy Rock B, Keane E, Mitchell CM. Culture, context, and sexual risk among Northern Plains American Indian Youth. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2152–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beauvais F. American Indians and alcohol. Alcohol Health Res World 1998;22:253–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Frank JW, Moore RS, Ames GM. Historical and cultural roots of drinking problems among American Indians. Am J Public Health 2000;90:344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Skewes MC, Blume AW. Understanding the link between racial trauma and substance use among American Indians. Am Psychol 2019;74:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.