Abstract

Background: Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe mood disorder that affects ∼5% of menstruating individuals. Although symptoms are limited to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, PMDD causes significant distress and impairment across a range of activities. PMDD is under-recognized by health care providers, can be difficult to diagnose, and lies at the intersection of gynecology and psychiatry. Thus, many patients are misdiagnosed, or encounter challenges in seeking care. The aim of this study was to examine patients' experiences with different health care specialties when seeking care for PMDD symptoms.

Methods: We examined data from the 2018 Global Survey of Premenstrual Disorders conducted by the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders (IAPMD). Patients rated their health care providers (general practitioners, psychiatrists, gynecologists, psychotherapists) in three key areas related to treatment of premenstrual mood complaints: interpersonal factors, awareness and knowledge of PMDD, and whether the patient was asked to track symptoms daily. Intraclass correlations examined between- and within-person variance. Multilevel regression models predicted ratings on each provider competency item, with ratings nested within individuals to examine the within-patient effect of provider type on outcomes.

Results: The sample included 2,512 patients who reported seeking care for PMDD symptoms. Regarding interpersonal factors, psychotherapists were generally rated the highest. On awareness and knowledge of PMDD, gynecologists and psychiatrists were generally rated the highest. Gynecologists were more likely than other providers to ask patients to track symptoms daily.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that different providers have different strengths in assessing and treating PMDD. Further, graduate and medical training programs may benefit from increased curricular development regarding evidence-based evaluation and treatment of PMDD.

Keywords: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, premenstrual syndrome, PMDD, PMS, mental health services, primary care

Introduction

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a mood disorder characterized by significant affective symptoms, including mood swings, irritability, depression, and anxiety, occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.1 During the luteal phase, these symptoms can impair functioning; interfering with activities of daily life,2 reducing productivity at home or at work, and impacting relationships,3 including marital and parental relationships.4 Functional impairment can persist for ∼1 week each menstrual cycle, representing significant burden.5 Although the point prevalence of PMDD (estimated based on daily ratings) is ∼5.5%,6 PMDD is under-recognized. While premenstrual mood complaints have been acknowledged in the medical community for nearly a century, PMDD was only recently (2013) made an official diagnosis in the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),7 and only last year (2019) classified as a disorder in the World Health Organization (WHO)'s International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).8 Thus, clinician education and knowledge of evidence-based PMDD assessment and treatment may be limited.9

Unfortunately, many who experience PMDD may not receive appropriate treatment due to lack of awareness of the disorder.7 Patients may have difficulty receiving an accurate diagnosis of PMDD, or finding a provider to provide evidence-based treatment.10 An additional barrier for patients is uncertainty regarding which provider to approach. In the ICD-11, PMDD is primarily listed under diseases of the genitourinary system, with a crosslisting under depressive disorders. However, the DSM-5 includes PMDD as a mood disorder. Clearly, PMDD is at a crossroads between mental and gynecologic health. General practitioners (i.e., primary care or family physicians) are often the first providers to see patients with PMDD. A patient's insurance may require her to present to her primary care physician before receiving a referral to a gynecologist or psychiatrist. Since PMDD is categorized as a mood disorder in the DSM-5 and reflects a neurobiological sensitivity to hormone changes,11,12 psychiatrists also see patients with PMDD symptoms. Because symptoms are temporally related to the menstrual cycle, patients may seek help from gynecologists. Given the characteristic mood symptoms, patients also present to nonmedical psychotherapists (e.g., psychologists, counselors, social workers). A study of patients in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France found that 90% of those seeking treatment for premenstrual symptoms received treatment for these symptoms from a gynecologist or primary care doctor.5 Most patients reported their premenstrual symptoms to their health care provider at an appointment made for another purpose,13 and consultations specifically for premenstrual mood complaints comprised <0.1% in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada.14

For health care providers, PMDD diagnosis and treatment present challenges. Due to the cyclic nature of the symptoms, accurate diagnosis requires prospective daily mood ratings for two menstrual cycles. Typically, a tool such as the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) is used, in which the patient rates daily a range of symptoms and impairment.15 Once the patient has completed daily ratings for at least two menstrual cycles, the provider may use a tool such as the Endicott scoring system or Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS) to determine whether the symptom profile meets DSM-5 criteria for PMDD diagnosis.16,17 However, only ∼12% of physicians diagnosing PMDD reported using prospective daily ratings for two cycles.9 Without daily ratings, providers may mistake the mood fluctuations as bipolar disorder, not recognizing that the cyclicity is tied to the menstrual cycle. Further, PMDD diagnosis may be complicated if there are comorbid affective diagnoses or premenstrual exacerbation of a mood or anxiety disorder.

Another challenge in managing PMDD is lack of clear treatment guidelines. Although treatment guidelines exist in the United Kingdom (The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG)'s Green-top Guidelines18) and from private companies in the United States (Up-to-Date Guidelines),19 there are currently no gynecologic (e.g., American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecologists [ACOG]) or psychiatric (e.g., APA) PMDD treatment guidelines for health care providers in the United States. The U.K. Green-top guidelines are geared toward premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a less severe syndrome that often includes physical symptoms as well as mild or moderate mood symptoms. The lack of guidance from professional organizations on PMDD treatment is a challenge for providers.

Finally, pharmacologic treatment of PMDD is unique from other mood disorders. Effective treatments for PMDD include SSRIs,20 extended-cycle oral contraceptives,21 and ovarian suppression using GnRH agonists22 or surgical oophorectomy.23 SSRIs are considered the gold standard treatments for PMDD. However, SSRI use for PMDD differs from the traditional indication for major depressive disorder (MDD).24 For PMDD, the SSRI may be taken only during the luteal phase, from ovulation or symptom onset.25–28 In addition, lower SSRI doses are effective for PMDD, compared with doses typically used for MDD.29 While some psychiatrists are familiar with prescribing SSRIs in the luteal phase or at lower doses for PMDD, many providers are not. Extended-cycle contraceptives are another treatment option, in which the patient has a hormone-free interval a few times per year as opposed to once every month.30 Among the COCs, Yaz is the only hormonal contraceptive that is approved for treating PMDD.21,31

PMDD causes distress and impairment similar to other mood disorders,32,33 so it is critical that providers are trained in its diagnosis and management. Diagnosing and treating PMDD require several competencies. First, the provider must be receptive to the patient's description of premenstrual symptoms, and willing to learn more about premenstrual symptoms if their knowledge is limited. Second, the provider must be aware of PMDD, the PMDD diagnostic procedure, and treatment options. Finally, the provider should be competent in treatment planning, including prospective daily mood ratings or referral to an expert in menstrual cycle suppression if indicated.

In this study, we describe the results of a large global survey of individuals with self-reported premenstrual disorders (n = 2,512). Patients reported on provider competence in three key areas related to treatment of premenstrual mood complaints: interpersonal factors (basic validation, compassion, willingness to learn about PMDD), awareness and knowledge (knowledge of PMDD diagnosis and effective treatments), and concrete indicators of expertise (e.g., use of daily ratings to make diagnosis). We focused on general practitioner physicians, psychiatrists, gynecologists, and psychotherapists. We sought to test three hypotheses: (1) With respect to interpersonal factors (compassion, validation, openness to learn), we expected psychiatrists and therapists to be rated highest, followed by gynecologists, then general practitioners. (2) With respect to PMDD knowledge, assessment, and effective treatment, we predicted that psychiatrists and gynecologists will be rated higher than other providers. (3) With respect to concrete indicators of expertise, we expected that psychiatrists and gynecologists will be rated higher than other providers.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional online survey design was used to examine the impact of provider type on a patient's ratings of provider competence in various areas. The survey was administered from September 24, 2018 to December 4, 2018. Participants were asked to rate each type of provider they had seen in the past in three areas of competency: (1) interpersonal factors, (2) awareness and knowledge of PMDD, and (3) concrete indicators of expertise. Specific survey items are detailed below.

Participants

Females with self-reported PMDD symptoms were recruited through social media posts by several organizations focused on PMDD awareness, peer support, education, and advocacy. Interested parties were directed to an online survey hosted by SurveyMonkey, which included a variety of questions, including demographics, nationality, premenstrual symptom characteristics, diagnosis, management, and impact of symptoms across areas of their life. Participants provided informed consent at the start of the survey. After the completion of data collection, data were deidentified and shared with the senior author, who obtained a determination from the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board that this work did not constitute Human Subjects Research (given that data were fully deidentified).

Measures

Prospectively confirmed PMDD (descriptive only)

While all participants who rated at least one provider in the survey (n = 2,512) were included in the present sample, we used a screening question to generate a descriptive variable indicating whether the person had received a prospective diagnosis of PMDD from a health care provider. Individuals were asked whether a medical professional had ever examined their daily symptom ratings across two cycles to determine their diagnosis. Participants responded, “No” (n = 1,714; 68.2%), “Yes, and they diagnosed me with PMDD” (n = 591; 23.5%), “Yes, and they diagnosed me with PME” (n = 30, 1.1%), or “Yes, and they diagnosed me with another, noncyclical disorder (not PMDD or PME)” (n = 177; 7%). For descriptive purposes, we coded those participants who endorsed the second option as “prospectively confirmed” cases of PMDD. Of note, this is not a guarantee that these patients did in fact have DSM-5 PMDD, since diagnosis using daily ratings is extremely complex and prone to human error.17 Further, it does not mean that the rest of the sample did not have DSM-5 PMDD, since most patients seeking care for PMDD are never asked to provide daily ratings at all.9 Therefore, this variable is calculated for descriptive purposes only, to note that ∼23.5% of the larger sample had been diagnosed with PMDD by a health care provider after the provider had examined daily symptom ratings across at least two cycles.

Provider competence survey

Patient advocates at the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders (www.iapmd.org), with input from members of Vicious Cycle: Making PMDD Visible (an international patient-led PMDD awareness project), and Me v PMDD (a startup focused on development of a PMDD daily rating mobile app) developed a list of competencies that are fundamental to treatment of PMDD. The list included items related to (1) interpersonal factors (“My provider showed compassion to me when I described my symptoms,” “My provider believed me when I spoke about my premenstrual symptoms,” “My provider had willingness to learn about PMDD if they had limited knowledge”); (2) awareness and knowledge (“My provider had knowledge of PMDD,” “My provider had knowledge of different treatment options for PMDD,” “My provider had knowledge about the efficacy of different treatment options for PMDD”); and (3) request to track symptoms daily (“My provider asked me to track my daily symptoms with my cycle for a minimum of two months”).

The participants were first asked whether they had sought care for their premenstrual symptoms from each of the following types of providers: (1) general practitioner (family physician or primary care provider), (2) gynecologist, (3) psychiatrist, and (4) other mental health providers (psychotherapists; e.g., psychologists, social workers, counselors). For each type of provider endorsed, the participant was asked to rate the provider on each of the competencies noted above. Providers were rated on a scale of 0 (No), 1 (Somewhat), or 2 (Yes).

Analytic plan

All analyses were carried out in SAS 9.4. Descriptive analyses were performed to characterize demographic features of the sample as well as to determine the percentage of the sample seeking care from each type of provider. The data structure was rating forms (for each specialty seen) at level 1, nested within patients at level 2—that is, each patient rated multiple provider specialties on the same rating form. Therefore, for each outcome we calculated the intraclass correlation (ICC), or the extent to which variability on a particular competence item was determined by the participant's general tendency to rate providers higher or lower (between-person variance) versus within-person variance in how a given person rated different providers. Higher ICCs indicate that a given provider rating is determined more by between-person differences in satisfaction, whereas lower ICCs indicate that a given provider rating is determined more by the unique patient-reported experiences of that particular provider. Second, we calculated means and standard deviations for each outcome by provider type.

Next, we utilized a separate multilevel regression model predicting ratings on each repeated competency item in SAS PROC MIXED, with ratings nested within people to examine the effect of provider type (pairwise contrasts). To account for nonindependence of ratings within a given patient, we included a random intercept at the patient level. We used category coding of repeated measures to conduct these contrasts. In addition, we created person-centered graphs of provider ratings on each item that help visualize the relative ratings of each provider for that outcome (relative to other providers). In these graphs, the 0 on the y axis represents the individual's mean rating of all providers on that outcome; higher values represent higher ratings of that specialty relative to the patient's ratings of other specialties, and lower values represent lower ratings of that specialty relative to other specialties.

Results

Participant flow and demographics

A total of 2,512 individuals provided ratings of at least one provider. Table 1 contains demographic information for the sample. The majority of the sample identified as female, were Caucasian, and had a postsecondary education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (n = 2,512)

| Category | Statistics |

|

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Age (mean = 33.72; SD = 8.05) | — | — |

| Prospective diagnosis with PMDD by health care provider | 591 | 23.5 |

| Age at menarche (mean = 12.48; SD = 1.61) | — | — |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 2,442 | 97.10 |

| Nonbinary | 56 | 2.23 |

| Other | 8 | 0.32 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight | 1,943 | 77.16 |

| Gay/lesbian | 58 | 2.30 |

| Bisexual | 276 | 10.96 |

| Pansexual | 78 | 3.10 |

| Queer | 92 | 3.65 |

| Other | 50 | 1.99 |

| Race | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 66 | 2.62 |

| Black or African | 51 | 2.03 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 77 | 3.06 |

| White/Caucasian | 2,177 | 86.56 |

| Other | 139 | 5.53 |

| Education | ||

| Left school at 16 with qualifications/diploma | 137 | 5.47 |

| Left school at 16 with no qualifications/diploma | 65 | 2.60 |

| Left school at 18 with qualifications/diploma | 362 | 14.46 |

| Left school at 18 with no qualifications/diploma | 26 | 1.04 |

| Apprenticeship | 52 | 2.08 |

| Associate's degree | 231 | 9.23 |

| Bachelor's degree | 853 | 34.07 |

| Master's degree | 396 | 15.81 |

| Ph.D. | 47 | 1.88 |

| Other | 335 | 13.38 |

| Income | ||

| <$15,000 | 309 | 13.51 |

| $15,000–$19,000 | 153 | 6.69 |

| $20,000–$24,999 | 140 | 6.12 |

| $25,000–$29,999 | 127 | 5.55 |

| $30,000–$34,999 | 164 | 7.17 |

| $35,000–$39,000 | 134 | 5.86 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 235 | 10.27 |

| $50,000–$79,999 | 449 | 19.62 |

| $80,000–$99,999 | 207 | 9.05 |

| $100,000 or above | 370 | 16.17 |

PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Descriptive analyses

Table 2 presents the characteristics of our primary variables, including means and standard deviations as well as the ICC of each rating scale item. The most common type of provider rated was general practitioner (GP), followed by gynecologists (GYN), then therapists (THER), then psychiatrists (PSYCHI). Regarding ICCs, most outcomes demonstrated ICCs ranging from 0.12 to 0.20, indicating that the bulk of the variance in provider ratings was attributable to differences between providers within a given patient (rather than patient-level differences in average ratings). A slightly higher ICC was present for the diagnostic expertise outcome of asking a patient to track symptoms (0.29; 29% of the variance due to between-patient differences). Being asked to track symptoms may therefore reflect differences at the patient level (e.g., nationality, age, comorbidity, etc.) to a greater extent than the other outcomes, although it was noted that the majority of the variance in this outcome was still related to provider-level differences within a given patient.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Each Outcome by Provider Type (n = 2,512)

| Provider type |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICCs (%) |

General practitioner (GP) |

Gynecologist (GYN) |

Psychiatrist (PSYCHI) |

Psychotherapist (THER) |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Did you see this kind of provider? | 1,569 (62.49) | 1,113 (44.47) | 754 (30.73) | 914 (36.89) | |

| Rating item | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Interpersonal factors | |||||

| “My provider showed compassion to me when I described my symptoms.” | 20.4 | 1.27 (0.77) | 1.36 (0.76) | 1.43 (0.75) | 1.65 (0.64) |

| “My provider believed me when I spoke about my premenstrual symptoms.” | 16.8 | 1.42 (0.69) | 1.62 (0.61) | 1.60 (0.64) | 1.67 (0.59) |

| “My provider had willingness to learn about PMDs if they had limited knowledge.” | 25.8 | 0.97 (0.81) | 1.11 (0.83) | 1.13 (0.84) | 1.23 (0.79) |

| Knowledge of PMDD and treatments | |||||

| “My provider had knowledge of PMDs.” | 15.2 | 0.95 (0.78) | 1.43 (0.70) | 1.11 (0.82) | 0.88 (0.79) |

| “My provider had knowledge of different treatment options for PMDs.” | 12.5 | 0.84 (0.76) | 1.36 (0.72) | 0.97 (0.80) | 0.67 (0.76) |

| “My provider had knowledge of the efficacy of different treatments for PMDs.” | 15.6 | 0.65 (0.72) | 1.13 (0.77) | 0.80 (0.79) | 0.54 (0.73) |

| Diagnostic expertise | |||||

| “My provider asked me to track my daily symptoms with my cycle for a minimum of two months.” | 29.5 | 0.62 (0.88) | 0.79 (0.94) | 0.68 (0.92) | 0.57 (0.86) |

ICC, intraclass correlation.

Hypothesis tests

Results are summarized below; contrasts from multilevel models comparing each type of provider can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of Multilevel Models Contrasting Each Provider Type on Patient-Reported Competency (n = 2,512)

| |

Contrasting general practitioners with… |

Contrasting gynecologists with… |

Contrasting psychiatrists with… |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynecologists |

Psychiatrists |

Therapists |

Psychiatrists |

Therapists |

Therapists |

|

| γ (SE) | γ (SE) | γ (SE) | γ (SE) | γ (SE) | γ (SE) | |

| Interpersonal factors | ||||||

| Showed compassion | 0.10* (0.03) | 0.09* (0.03) | 0.38* (0.03) | 0.08* (0.03) | 0.28* (0.03) | 0.19* (0.03) |

| Believed me | 0.19* (0.02) | 0.18* (0.03) | 0.25* (0.02) | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.07* (0.03) |

| Willing to learn more | 0.11* (0.04) | 0.12* (0.04) | 0.21* (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.10* (0.04) | 0.09* (0.04) |

| Knowledge of PMDD and treatments | ||||||

| Aware of PMDD | 0.48* (0.03) | 0.16* (0.03) | −0.10* (0.03) | −0.32* (0.04) | −0.58* (0.03) | −0.25* (0.04) |

| Knew treatment options | 0.52* (0.03) | 0.15* (0.03) | −0.18* (0.03) | −0.37* (0.04) | −0.71* (0.03) | −0.33* (0.04) |

| Knew treatment efficacies | 0.49* (0.03) | 0.16* (0.03) | −0.12* (0.03) | −0.33* (0.04) | −0.61* (0.03) | −0.28* (0.04) |

| Diagnostic expertise | ||||||

| Used daily ratings for diagnosis | 0.17* (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.13* (0.04) | −0.24* (0.04) | −0.11* (0.04) |

value represents statisitcal significance (p = 0.05).

SE, standard error.

Interpersonal factors

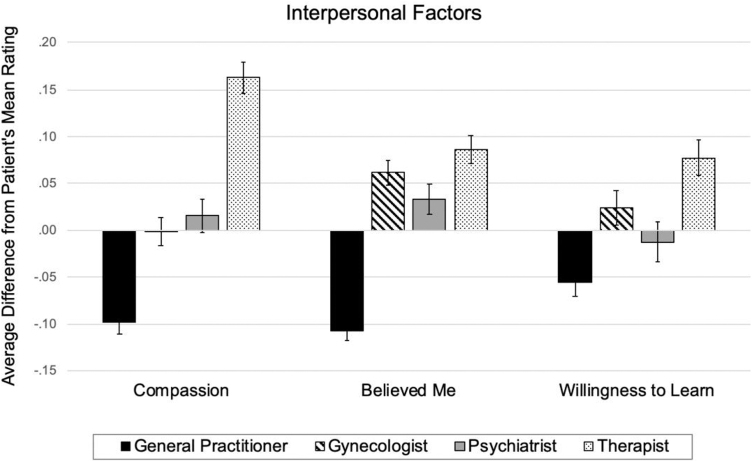

We hypothesized that psychiatrists (PSYCHI) and psychotherapists (THER) would be rated the highest with respect to interpersonal factors, followed by gynecologists (GYN) and then general practitioners (GP) (PSYCHI = THER > GYN > GP). Results of multilevel models testing these predictions are presented in Table 3 and depicted in Figure 1. As predicted, across the interpersonal items (compassion, believing the patient, and willingness to learn about the diagnosis), general practitioners were generally rated the lowest. Therapists were generally rated the highest, and psychiatrists and gynecologists were rated in between.

FIG. 1.

Within-person differences in PMDD patient ratings of various providers on interpersonal factors. PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

With respect to the compassion item, general practitioners were rated significantly lower than all other providers, gynecologists were rated lower than both psychiatrists and therapists, and therapists were rated higher than psychiatrists. On the “My provider believed me” item, general practitioners were again rated significantly lower than all other providers, there were no differences between gynecologists and psychiatrists, and therapists were rated higher than psychiatrists. With respect to willingness to learn more about PMDD, general practitioners were rated lower than all other providers, there were no differences between gynecologists and psychiatrists, and therapists were rated higher than both gynecologists and psychiatrists.

In sum, there was support for our hypothesis that general practitioners would be rated lower on interpersonal factors and psychiatrists/therapists would be rated higher; however, we found an advantage in this area for therapists, and only compassion (and not validation or openness to learn) was higher among psychiatrists than gynecologists.

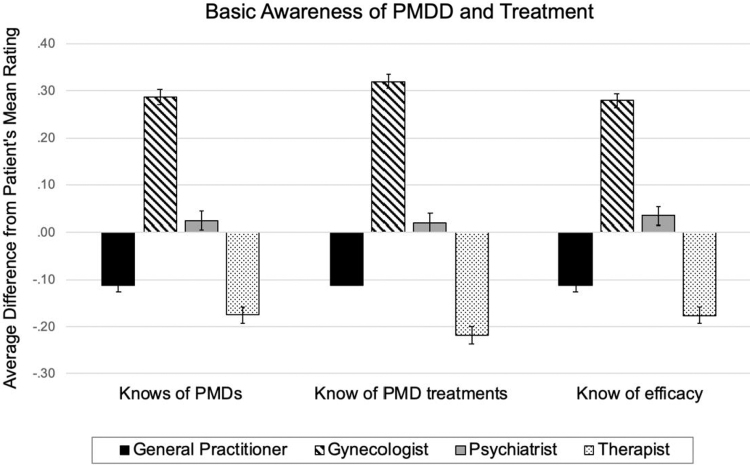

Awareness of PMDD and treatment

We hypothesized that psychiatrists and gynecologists would be rated the highest with respect to awareness of PMDD and basic treatment, followed by general practitioners and therapists (PSYCHI = GYN > GP = THER). Results of multilevel models testing these predictions are presented in Table 3 and depicted in Figure 2. As predicted, gynecologists and psychiatrists were generally rated the highest, with therapists being rated the lowest and general practitioners rated in between.

FIG. 2.

Within-person differences in PMDD patient ratings of various providers on basic awareness and knowledge of PMDD and its treatment.

All three outcomes (awareness of PMDD, knowledge of treatment options, knowledge of treatment efficacy) had an identical pattern of results (Table 3). With respect to awareness and treatment knowledge, general practitioners were rated significantly lower on awareness and knowledge items than gynecologists and psychiatrists but were rated higher than therapists. Gynecologists were rated higher in awareness and knowledge than all other providers, and contrary to our predictions, were rated as more knowledgable than psychiatrists. Therapists were rated lower than all other providers.

To summarize, there was support for our hypothesis that general practitioners and therapists would be rated lower on awareness of PMDD and basic treatment than gynecologists and psychiatrists. However, we found that gynecologists had an advantage in this area, and that psychiatrists were rated lower than gynecologists in every item of this category.

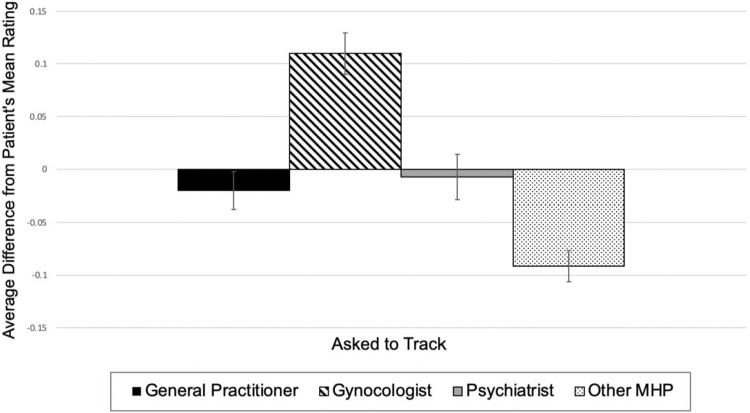

Diagnostic expertise: request to track symptoms daily

We hypothesized that psychiatrists and gynecologists would be rated the highest followed by general practitioners and therapists (PSYCHI = GYN > GP = THER) with respect to requesting patients track symptoms daily, which is an indicator of expertise. Results of multilevel models testing this prediction are presented in Table 3 and depicted in Figure 3. On the item of requesting patients track symptoms daily, gynecologists were rated higher than all other providers and psychiatrists were rated higher than therapists. It was unexpected that psychiatrists were rated as worse than gynecologists, and were no different from general practitioners on this variable, although they were more likely than therapists to ask a patient to track symptoms.

FIG. 3.

Within-person differences in PMDD patient ratings of various providers on an indicator of diagnostic expertise (asking the patient to track symptoms daily).

To summarize, there was support for our hypothesis that gynecologists would be rated higher than general practitioners and therapists on requests to track daily symptoms, which is an indicator of diagnostic expertise. However, psychiatrists rated lower than gynecologists on this measure, contrary to our hypothesis.

Discussion

This study examined how patients seeking care for perceived PMDD symptoms rated different types of health care providers in terms of interpersonal factors, awareness of PMDD, and diagnostic expertise. We hypothesized that psychiatrists and therapists would be rated higher than other providers on interpersonal factors, and that gynecologists and psychiatrists would be rated higher than other providers on knowledge and expertise. With respect to interpersonal factors, our results were largely supported, although gynecologists performed similarly to psychiatrists, and therapists performed better than all other providers. With respect to knowledge and expertise, gynecologists outperformed all other providers, with psychiatrists notably underperforming relative to expectations.

Given that PMDD is classified as a psychiatric disorder in the DSM-5, with core symptoms related to emotional dysfunction, it is surprising and potentially concerning that patients perceived psychiatrists to be less knowledgable than gynecologists. There are several potential reasons that psychiatrists underperformed in knowledge and expertise regarding PMDD. First, PMDD is a relatively new addition to the DSM-5, introduced in 2013. It is possible that providers, particularly those practicing since before 2013, have not received education and training regarding PMDD. Data from the National Task Force on Women's Reproductive Mental Health in the United States reflect this, showing that few psychiatry residency programs include reproductive psychiatry in the curriculum, with barriers including lack of qualified faculty and lack of time.34 The APA provides core competencies for residency training as well as a recommended online curriculum through the APA Learning Center; the online curriculum (Supplemental Education and Training [SET]) for psychiatry residents has >50 recommended topics (e.g., practice management, special populations), but neither PMDD, PMS, nor any other reproductive mood disorder is included.35 At the fellowship level, because reproductive psychiatry is not recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, there are not accredited fellowships, standardized curricula, or subspecialty examinations in reproductive psychiatry.36 Finally, neither the APA nor ACOG has provided treatment guidelines for physicians in the United States treating PMDD, and the United Kingdom's RCOG guidelines are labeled for PMS and not PMDD. Together, these factors may have limited knowledge regarding PMDD among psychiatrists. While there are little data on psychiatrists specifically, a study of physicians in the United States found that providers encountering individuals with premenstrual complaints either were not aware of or were not practicing the guidelines of using daily ratings to diagnose PMDD.9

Gynecologists were generally rated the highest among all categories of PMDD knowledge and treatment. A prior study found that patients were more likely to initially present with premenstrual mood complaints to an OB-GYN provider than to a primary care provider, with OB-GYNs reported seeing 6–15 new PMDD cases per year compared with 0–10 new cases per year for primary care physicians.9 Interestingly, a study of patients seeking gynecologic care found that 59% would not seek help regarding mental health concerns from their gynecologist, feeling it was an inappropriate setting for mental health care or that gynecologists do not have sufficient training in mental health care.37 While gynecologists may not view mental health concerns as within their area of expertise, they were more accurate in diagnosing PMDD than MDD based on case descriptions.38 Indeed, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics lists PMS/PMDD as 1 of 64 Medical Student Educational Objectives during the OB-GYN clerkship; in other words, from their first exposure to gynecology, medical students are expected to recognize and treat PMS and PMDD as gynecologic concerns. Given that the APA and the Association of Academic Psychiatry do not have similar objectives regarding PMS/PMDD education at the medical student or resident level, it makes sense that gynecologists receive higher ratings on knowledge and treatment by PMDD patients.

These results have several implications for patients and patient advocates. First, the findings suggest that different providers have different strengths in assessing and treating PMDD. For individuals experiencing PMDD symptoms, satisfactory care may be achieved by seeking help from multiple providers, some of whom may be able to provide compassion, whereas others may be able to provide specific guidance and treatment. Health care utilization can also be supplemented by peer support, which many patients find helpful throughout the treatment process.

In addition, our results have implications for health care providers. Training in medical school, residency, and fellowships, particularly in primary care, psychiatry, and OB-GYN, should include information on reproductive mood disorders such as PMDD.39 However, only around half of residency programs in the United States include training in reproductive psychiatry.34 As early as medical school, the core psychiatry clerkship should include diagnosis and treatment of PMDD within its educational objectives. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) does include knowledge of PMDD as a recommended competency of residents,40 thus it is concerning that general practitioners received low ratings on awareness, knowledge, and treatment of PMDD. Especially for patients who do not have access to multiple providers, it is essential that general practitioners are trained in the importance of daily symptom ratings for PMDD diagnosis and encouraged to utilize evidence-based collaborative care models for patients presenting with mental health concerns.41,42 Continuing education for physicians could also promote knowledge and awareness of PMDD. To address these gaps in provider education, the National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry (NCRP) was recently developed in the United States.43 The NCRP is an interactive online curriculum that aims to educate mental health care providers in reproductive psychiatry, and includes modules on menstrual-cycle-related mood symptoms, including PMDD, PMS, and PME of another mood disorder. While they cannot prescribe medication in most locations, psychologists can contribute to PMDD care through (1) assessment and diagnosis of PMDD using daily ratings, (2) referral to a prescriber for SSRI or oral contraceptive treatment, (3) helping a patient monitor treatment effects and side effects using daily ratings, and (4) using psychotherapies to reduce impairment associated with PMDD symptoms.44 Therapists may also benefit from PMDD training programs that focus on evidence-based diagnosis and case management. Finally, it is important that leading professional organizations in psychiatry, gynecology, and psychology publish (or endorse existing) evidence-based treatment guidelines for PMDD. This includes, but is not limited to, the APA, ACOG, the Royal College of Psychiatry (RCOP), and the American Psychological Association.

This study also had several important strengths. First, the use of a survey developed with patient advocates has the advantage of infusing the lived experience of actual patients into this work; future studies should expand on this approach to include standardized measures of patient experiences based on carefully validated surveys. Second, the use of multilevel models to investigate the effect of provider specialty (type) on patient ratings of provider performance is another important strength. This approach accounts for the nested nature of the ratings (multiple providers being rated by the same patient), and allowed us to isolate and predict the variance in provider performance ratings that is due to provider characteristics (e.g., provider specialty) while setting aside the variance in provider performance ratings that is due to patient characteristics.

This study had several important limitations. First, there are limitations of the patient-designed questionnaire used in this sample. These limitations primarily revolve around assumptions about the characteristics of the patient (e.g., assuming that all survey respondents actually have PMDD or are knowledgable about PMDD treatments) or the provider (e.g., assuming that most providers lack knowledge of PMDD). While the prioritization of patient ideas and priorities in research studies is important, patient-centered study design would ideally involve a structured, collaborative dialog between patients, experienced clinicians, and scientists with relevant expertise in survey development and validation. Second, it is possible that the contrasts between providers presented here are influenced by some selection bias based on response to initial treatments; patients who reach adequate symptom remission with first- or second-line treatments may be less likely to see more than one type of provider. Third, we asked participants to rate their experiences with provider categories for PMDD complaints across their entire treatment history; this long time frame could have led to less reliable ratings in some cases (e.g., when treatment occurred decades ago, or when multiple providers from a single category were seen across the lifetime). Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of the survey prevents us from drawing conclusions about the true diagnostic status of our participants; while 23.5% of the sample had received a diagnosis with PMDD by a provider using daily ratings to confirm the pattern of symptoms, this does not equate to a reliable diagnostic subgrouping of the sample. However, the focus of this article is on treatment experiences among those who seek care for perceived PMDD symptoms (rather than among those who have PMDD), and the results still provide important information about treatment seekers' experiences with various specialties. Finally, it is important to note that rating the competence and knowledge of one's provider relies on a minimum amount of patient knowledge; therefore, these ratings probably reflect perceived provider knowledge or competence, and may not actually reflect provider competence with respect to evidence-based guidelines.

PMDD has significant negative effects on a person's professional and personal life across the reproductive life span, including work absenteeism, decreased work productivity, impairment in daily activities, and interference with relationships.3 While impairment is most significant in the luteal phase, it may extend into the perimenstrual window, with the symptoms, or their negative consequences, persisting into the early follicular phase.45 PMDD is associated with cumulative 3.8 years of disability, measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), for each woman with the disorder; across the United States alone, this represents >14 million DALYs lost.32 Given these negative effects, access to appropriate PMDD diagnosis and treatment by their providers is paramount. This study suggests that there is room for improvement in providers' interpersonal approach, knowledge about PMDD, and expertise in diagnosing and treating PMDD, and that this varies by specialty. Improvements in training and promoting awareness of PMDD, particularly given its wide impact and public health relevance, may strengthen providers' ability to furnish quality care.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders (IAPMD) that designed and carried out data collection for this study in collaboration with Vicious Cycle and Me v PMDD, as well as the time volunteered by the survey respondents.

Authors' Contributions

L.H. contributed to conceptualization and planning of analyses, wrote and revised the final draft; H.S. contributed to conceptualization of the hypotheses and writing the first draft; J.B. contributed to writing and editing the final draft; S.R. cleaned and managed data and assisted with data analyses; T.E.M. contributed to conceptualization of the study and hypotheses, writing the first draft, performing data analyses, and editing the final draft. B.B. and L.M. directed survey development and survey administration.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; K23MH107831) (LH), (NIMH R00MH109667) (TEM) and the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders (IAPMD).

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schoep ME, Nieboer TE, van der Zanden M, Braat DDM, Nap AW. The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: A survey among 42,879 women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220:569..e1–569.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heinemann LAJ, Minh TD, Heinemann K, Lindemann M, Filonenko A. Intercountry assessment of the impact of severe premenstrual disorders on work and daily activities. Health Care Women Int 2012;33:109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003;28 Suppl 3:55–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hylan TR, Sundell K, Judge R. The impact of premenstrual symptomatology on functioning and treatment-seeking behavior: Experience from the United States, United Kingdom, and France. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 1999;8:1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gehlert S, Song IH, Chang C-H, Hartlage SA. The prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a randomly selected group of urban and rural women. Psychol Med 2009;39:129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. . Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:465–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [WHO] Word Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. (11th Ed.; ICD-11). Geneva: WHO, 2019. Available at: https://icd.who.int/ Accessed March 25, 2021.

- 9. Craner JR, Sigmon ST, McGillicuddy ML. Does a disconnect occur between research and practice for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) diagnostic procedures? Women Health 2014;54:232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osborn E, Wittkowski A, Brooks J, Briggs PE, O'Brien PMS. Women's experiences of receiving a diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A qualitative investigation. BMC Womens Health 2020;20:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schmidt PJ, Martinez PE, Nieman LK, et al. . Exposure to a change in ovarian steroid levels but not continuous stable levels triggers PMDD symptoms following ovarian suppression. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174:980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei S-M, Schiller CE, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. The role of ovarian steroids in affective disorders. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018;23:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robinson RL, Swindle RW. Premenstrual symptom severity: Impact on social functioning and treatment-seeking behaviors. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000;9:757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weisz G, Knaapen L. Diagnosing and treating premenstrual syndrome in five western nations. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1498–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Endicott J, Harrison W. Daily rating of severity of problems form. In: Department of Research Assessment and Training. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily record of severity of problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Girdler SS, Schmalenberger KM, et al. . Toward the reliable diagnosis of DSM-5 premenstrual dysphoric disorder: The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS). Am J Psychiatry 2017;174:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Premenstrual Syndrome, Management (Green-top Guideline No. 48). Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, 2016. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg48/ Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 19. Yonkers K, Casper R. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. UptoDate.com Published online 2019. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-premenstrual-syndrome-and-premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder Accessed March 25, 2021.

- 20. Steiner M, Pearlstein T, Cohen LS, et al. . Expert guidelines for the treatment of severe PMS, PMDD, and comorbidities: The role of SSRIs. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2:CD006586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Ismail KMK, Jones PW, O'Brien PMS. The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without “add-back” therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: A meta analysis. BJOG 2004;111:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cronje WH, Vashisht A, Studd JWW. Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy for severe premenstrual syndrome. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2152–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eriksson E, Ekman A, Sinclair S, et al. . Escitalopram administered in the luteal phase exerts a marked and dose-dependent effect in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freeman EW. Luteal phase administration of agents for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. CNS Drugs 2004;18:453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Sammel MD, Ferdousi T, Lin H. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers KA, Freeman E, Stout AL, Cohen L. Efficacy of intermittent, luteal phase sertraline treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, Farfel GM, Gillespie JA. Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: Efficacy of 3 dosing strategies. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1624–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiegratz I, Hommel HH, Zimmermann T, Kuhl H. Attitude of German women and gynecologists toward long-cycle treatment with oral contraceptives. Contraception 2004;69:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pearlstein TB, Bachmann GA, Zacur HA, Yonkers KA. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception 2005;72:414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003;28 Suppl 3:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pearlstein T, Steiner M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Burden of illness and treatment update. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2008;33:291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Osborne LM, Hermann A, Burt V, et al. . Reproductive psychiatry: The gap between clinical need and education. AJP 2015;172:946–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. SET for Success, 2020. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/residents-medical-students/residents/set-for-success Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 36. Nagle-Yang S, Miller L, Osborne LM. Reproductive psychiatry fellowship training: Identification and characterization of current programs. Acad Psychiatry 2018;42:202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bennett IM, Palmer S, Marcus S, et al. . “One end has nothing to do with the other”: Patient attitudes regarding help seeking intention for depression in gynecologic and obstetric settings. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009;12:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hill LD, Greenberg BD, Holzman GB, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists' attitudes toward premenstrual dysphoric disorder and major depressive disorder. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2001;22:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barkin JL, Osborne LM, Buoli M, Bridges CC, Callands TA, Ezeamama AE. Training frontline providers in the detection and management of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. J Womens Health 2020;29:889–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents. Published online 2015.

- 41. Overbeck G, Davidsen AS, Kousgaard MB. Enablers and barriers to implementing collaborative care for anxiety and depression: A systematic qualitative review. Implement Sci 2016;11:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang H, Tabb KM, Cerimele JM, Ahmed N, Bhat A, Kester R. Collaborative care for women with depression: A systematic review. Psychosomatics 2017;58:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry. NCRP. Available at: http://ncrptraining.org/ Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 44. Eisenlohr-Moul T. Premenstrual disorders: A primer and research agenda for psychologists. Clin Psychol 2019;72:5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chawla A, Swindle R, Long S, Kennedy S, Sternfeld B. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Is there an economic burden of illness? Med Care 2002;40:1101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]