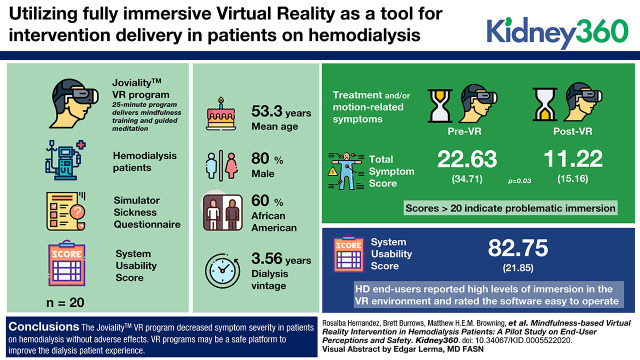

Visual Abstract

Keywords: dialysis, alternative therapies, hemodialysis, mindfulness/meditation, psychological wellbeing, symptom management, virtual reality

Abstract

Background

Virtual reality (VR) is an evolving technology that is becoming a common treatment for pain management and psychologic phobias. Although nonimmersive devices (e.g., the Nintendo Wii) have been previously tested with patients on hemodialysis, no studies to date have used fully immersive VR as a tool for intervention delivery. This pilot trial tests the initial safety, acceptability, and utility of VR during maintenance hemodialysis treatment sessions—particularly, whether VR triggers motion sickness that mimics or negatively effects treatment-related symptoms (e.g., nausea).

Methods

Patients on hemodialysis (n=20) were enrolled in a phase 1 single-arm proof-of-concept trial. While undergoing hemodialysis, participants were exposed to our new Joviality VR program. This 25-minute program delivers mindfulness training and guided meditation using the Oculus Rift head-mounted display. Participants experienced the program on two separate occasions. Before and immediately after exposure, participants recorded motion-related symptoms and related discomfort on the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire. Utility measures included the end-user’s ability to be fully immersed in the virtual space, interact with virtual objects, find hardware user friendly, and easily navigate the Joviality program with the System Usability Scale.

Results

Mean age was 55.3 (±13.1) years; 80% male; 60% Black; and mean dialysis vintage was 3.56 (±3.75) years. At the first session, there were significant decreases in treatment and/or motion-related symptoms after VR exposure (22.6 versus 11.2; P=0.03); scores >20 indicate problematic immersion. Hemodialysis end-users reported high levels of immersion in the VR environment and rated the software easy to operate, with average System Usability Scale scores of 82.8 out of 100.

Conclusions

Patients on hemodialysis routinely suffer from fatigue, nausea, lightheadedness, and headaches that often manifest during their dialysis sessions. Our Joviality VR program decreased symptom severity without adverse effects. VR programs may be a safe platform to improve the experience of patients on dialysis.

Key Points

This pilot trial tests the initial safety, acceptability, and utility of virtual reality during hemodialysis treatment sessions.

Our Joviality program, a fully immersive virtual reality environment, decreased dialysis-related symptom severity without adverse effects.

Fully immersive virtual reality programs may be a safe platform to improve the experience of patients on dialysis.

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is an evolving technology that immerses end users in a digitally fabricated, yet realistic and lifelike environment. End users wear a head-mounted display (HMD) that uses tracking systems and physical motion, such as eye or head movements, to navigate a digitally created virtual world, which can replicate realistic settings (e.g., 360° video of a garden or beach) or complex science-fiction environments (1). VR is most frequently used in video gaming and for simulation training with clinicians and military personnel (2–4). VR has also been successfully used in treatment plans for pain management (e.g., burn victims), physical rehabilitation, and psychologic phobias (e.g., acrophobia or fear of heights), with evident improvements in emotional wellbeing and lessening of physical complaints (5–9).

The benefits of chairside exposure to VR remain largely unexplored in patients on hemodialysis (HD). Previous studies on VR-related experiences have focused on nonimmersive gaming devices (e.g., Nintendo Wii) (10–12). Therapeutic uses of VR might provide similar benefits to video gaming, including distraction, entertainment, and engagement, which allow patients to feel they can escape the mundane clinical setting, where they spend over ≥9 h/wk (13,14). VR might provide additional benefits through embedding of evidence-based programming (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction) (15). Such programming could improve a patient’s emotional wellbeing, quality of life, and disease progression.

There might also be negative side effects of using VR that must be explored before widespread use. Most notably, VR can induce cybersickness symptoms of fatigue, nausea, dizziness, and general discomfort. Testing for cybersickness is particularly relevant for this patient population, because cybersickness symptoms are often similar to common symptoms experienced by patients on HD that are related to intradialytic hypotension, osmotic shifts during dialysis, or other causes. Therefore, nausea and other routine discomfort associated with HD therapy might be exacerbated by VR. Another concern is the extended periods of noise experienced during dialysis. Noise creates a unique environmental exposure that might lead to sensory overload and adverse effects when combined with VR (16).

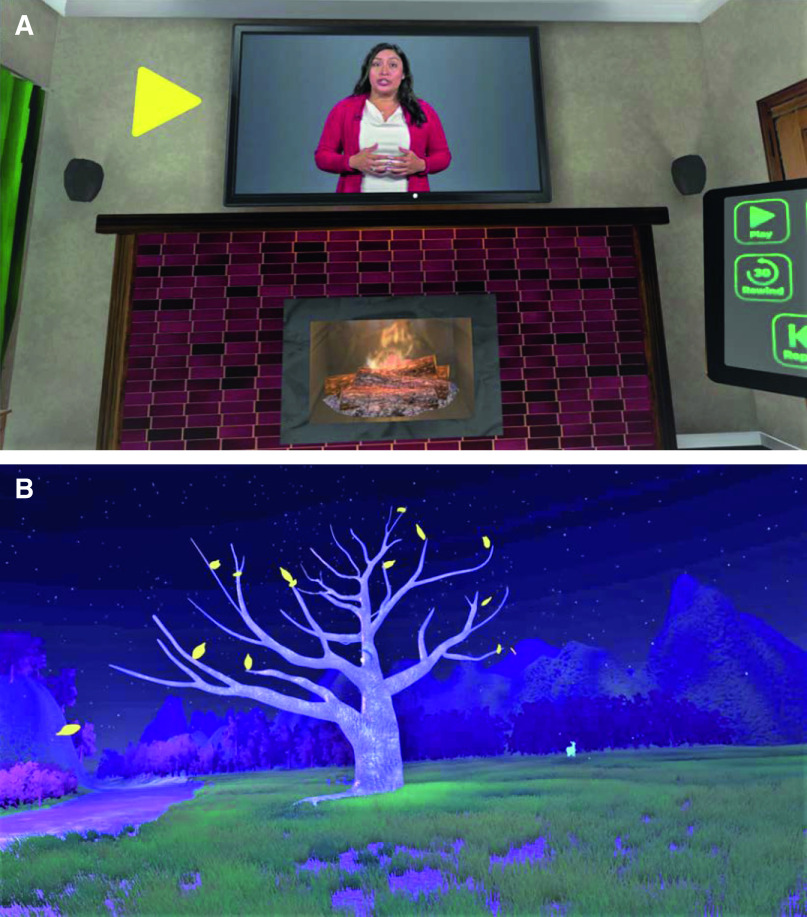

This pilot study tests the initial safety, acceptability, and utility of VR during regularly scheduled HD treatment. We employ a 25-minute mindfulness/meditation exercise in a fully immersive VR program delivered through an HMD (see Figure 1). Our central hypothesis is that the VR program will be immersive, cause no adverse effects, and create a positive experience. We specifically expect patients will report high levels of spatial presence, low levels of nausea and discomfort, and describe their experience as enjoyable, understandable and clear, and beneficial. Our primary goal is to determine whether VR exacerbates symptoms routinely experienced during maintenance HD—mainly, headaches, nausea, lightheadedness, or fatigue.

Figure 1.

Oculus Rift head-mounted display.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Data for this phase 1 single-arm proof-of-concept trial were collected from 20 participants between October and November 2019 (Figure 2). Participants were recruited from an HD clinic in Urbana-Champaign, IL, using the following inclusion criteria: (1) recipient of HD treatment for ≥3 months, (2) ≥18 years of age, (3) sufficient visual and audio acuity to navigate the VR world unaided, and (4) English fluency. Exclusion criteria included: (1) unavailability for the entire study period, (2) cognitive impairments suggesting dementia, (3) physical/sensory limitations restricting use of an HMD, and (4) history of epilepsy, seizures, or vertigo. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign approved the trial (Institutional Review Board number 19190). Written informed consent was obtained for all enrolled participants. The research activities being reported are consistent with Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

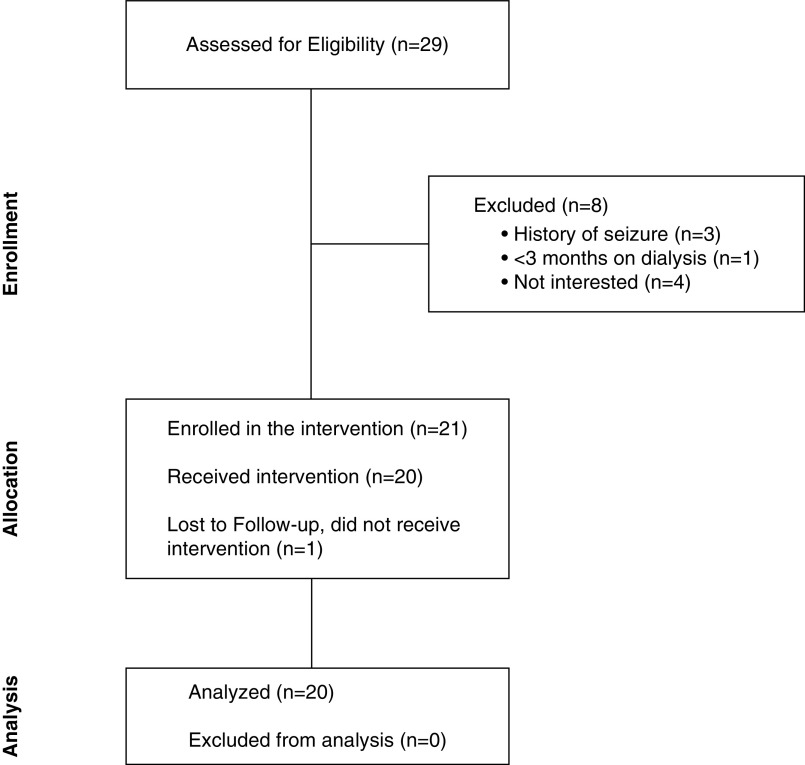

Figure 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart diagram.

Recruitment consisted of research staff approaching potentially eligible participants chairside, during regularly scheduled HD treatment sessions. Patients were provided study details and answers to their questions. Patients interested in enrolling underwent screening to determine full eligibility. With the exception of cognitive impairment, which was assessed with the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (17), all eligibility requirements were on the basis of self-reported data. Eligible patients then provided written informed consent and completed several questionnaires (see Measures and Assessment Procedures) immediately before participation.

VR Intervention

We used the Oculus Rift CV1 (1080×1200 resolution per eye, a 90 Hz refresh rate, and a 110° field of view) (Facebook Technologies, LLC) to expose HD participants to Joviality, our newly designed VR mindfulness/meditation program. VR immersion occurred 30 minutes after HD treatment initiation or during the final hour of dialysis. This program was adapted from the Developing Affective Health to Improve Adherence (DAHLIA) positive psychologic curriculum developed by Cohn et al. (2014) (18). Joviality focuses on the DAHLIA module that is readily translatable to a solitary VR experience: techniques of mindful awareness and meditation.

A transdisciplinary team of digital artists, computer programmers, and engineers developed the Joviality program. The textual content of DAHLIA related to mindful awareness and meditation was adapted for VR, with the agile design principles of brainstorming, storyboarding, testing, and refining (19,20). The finished program places end-users in an armchair within a virtual living room, where they follow visual and auditory stimuli and instructions on a flatscreen television (Figure 3A). The television displays a prerecorded video, where the principal investigator of the trial explains the concept of mindfulness using the DAHLIA curriculum. This explanation focuses on learning and practicing nonjudgmental and intentional awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations in the present moment. Participants then learn techniques to practice mindfulness in their everyday life outside of the dialysis center. After the delivery of this mindfulness/mediation lesson, participants are teleported to a virtual garden for a 12-minute guided meditation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Virtual reality settings for the JovialityTM program for delivery of mindfulness education and engagement in guided meditation. (A) Living room for mindfulness education. (B) Virtual garden for guided meditation.

The entire 25-minute intervention was repeated on two separate occasions during consecutive HD treatment sessions (e.g., Monday and Wednesday, or Tuesday and Thursday). Research staff assisted participants in fitting the HMD to ensure a comfortable experience. Given the limited hand mobility of HD end-users, we opted not to use hand controllers; instead, participants navigated the VR environment with head movement (e.g., nod). HMDs were removed from participants by research staff when severe motion sickness was evident or a dialysis-related event interfered with the dialysis session. Staff notified the attending clinician of symptomatology for immediate follow-up.

Measures

Measures consisted of end-users’ subjective ratings on paper-and-pencil questionnaires administered before and after the intervention (Table 1). Research staff were available to assist participants in completing these assessments.

Table 1.

Sequencing of assessment measures for the Joviality program

| Surveys and Data Collection Assessments | Exposure 1 | Exposure 2 | Postinterventiona | ||||

| Pre Virtual Reality | VR Session One | Post Virtual Reality | Pre Virtual Reality | VR Session Two | Post Virtual Reality | ||

| VR/HD symptoms (SSQ) | X | X | X | X | |||

| Immersion in VR environment (IPQ) | X | X | |||||

| Usability of VR equipment (SUS) | X | ||||||

| Feedback from end-users on VR exposure | X | ||||||

| Clinical staff assessments of VR treatment | X | ||||||

VR, virtual reality; HD, hemodialysis; SSQ, Simulator Sickness Questionnaire; IPQ, IGroup Presence Questionnaire; SUS, System Usability Scale.

Postintervention measures were completed after both exposure sessions.

The main outcome of the trial was the safety of the VR program. This was evaluated with the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). The SSQ is a 16-item questionnaire that measures an end-user’s current feelings of cybersickness and other adverse motion-related symptomatology (21). Items are measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), with higher scores indicating greater cybersickness. In addition to generating a total score, subscales captured domains of symptoms related to oculomotor functioning, nausea, and disorientation. Because items of the SSQ overlap with HD-related symptoms, participants completed the questionnaire both before and after both VR exposures to test for worsening (or improvements) of symptoms.

The subjective ratings of presence and immersion in the VR program was measured with the IGroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) (22–24). This 14-item questionnaire includes three subscales: (1) Spatial Presence, which captures the extent to which end-users feel physically present in the space; (2) Involvement, which evaluates the level to which end-users are captivated and estimates their ability to focus on the content presented; and (3) Experienced Realism, which gauges whether the virtual environment mimics real-life objects and interactions. The questionnaire also includes a single item outside of the subscales that asks, “In the computer-generated world, I had a sense of ‘being there’.” This item measures the overall level of presence. All items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater immersion and felt presence. The mean IPQ score is calculated by averaging across the 14 items, which generates a score ranging from 1 (low level of presence) to 7 (high level of presence). An average score is also calculated for each of the subscales. Presence via the IPQ was measured after both VR experiences.

The subjective ratings of the VR device and software was captured with the System Usability Scale (SUS) (25,26). This ten-item questionnaire includes such items as “I would imagine that most people would learn to use this VR program very quickly.” Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A total score is computed by adding all items and generating a score ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores are indicative of greater usability, and scores ≥80 indicate that end-users enjoyed interacting with the system so much they are likely to recommend its use to others (27). Usability via the SUS was measured after the second VR exposure only.

Participants were also asked what they liked and disliked most about the Joviality program, and how they thought the program and VR experience could be improved through qualitative feedback. Medical staff also rated the extent to which VR immersion promoted isolationism, noise pollution affected the clinic space, and VR interfered with normal clinical practices in Clinical Staff Assessments (Supplemental Appendix A). Survey data from clinical staff were anonymous and limited to those on the dialysis floor, including nurses or technicians. All of these measures were collected after the second VR exposure only.

Several other measures were collected through surveys with patients. Sociodemographic characteristics included age (in years), sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, number of years of formal education, annual household income, employment status, health insurance coverage (absent versus present), and place of nativity (US born versus foreign born). Health status included previous history and/or current prevalence of hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus. Last, data on VR past use were collected to control for different effects among first-time VR users and repeat users. To gather these data, we asked participants whether they were familiar with VR technology and whether they previously used an HMD. Items used a dichotomous response (yes, no) (28).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics 23 for Windows, 2015). Descriptive statistics summarized baseline characteristics of patients. Paired sample t tests determined the magnitude of pre and post changes in the questionnaire measures collected before and after VR exposure (see Table 1 for sequencing of study measures). To test for effect modifiers, independent sample t tests were used with SSQ, IPQ, and the SUS scores within sex, age (<55 versus ≥55), race/ethnicity, and previous VR experience (yes versus no) subgroups. Qualitative data of HD end-user experiences were examined for emergent themes. Assessments of clinical staff were presented as percentages as these were dichotomous in nature.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 2 presents the characteristics of trial participants (n=20). Ages ranged from 34 to 84 years (M=55.25, SD=13.12). Similar to the demographic characteristics of the patients of the HD enrollment site, the majority (80%) of participants were male. (Only five females were available and approached during trial enrollment.) In total, 60% of participants identified as Black and the remainder identified as non-Hispanic White. The average number of years participants were on dialysis was 3.56 (SD=3.75). On average, participants reported 13.5 years of formal schooling, and 35% had annual household incomes below US$20,000. A high prevalence of comorbid cardiovascular disease risk factors were reported, including 85% of participants with hypertension, 50% with diabetes, and 25% with hypercholesterolemia. Finally, 65% had previous knowledge of VR technology and 30% had used an HMD in the past.

Table 2.

Description of participants who completed the Joviality trial (n=20)

| Characteristics | Result |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 55.25 (13.12) |

| Male, n (%) | 16 (80) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Black | 12 (60) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 8 (40) |

| Married, n (%) | 8 (40) |

| Dialysis vintage, yr, mean (SD) | 3.56 (3.75) |

| Retired or unable to work, n (%) | 9 (45) |

| Schooling, yr, mean (SD) | 13.50 (3.38) |

| Income <$20,000, n (%) | 7 (35) |

| US born, n (%) | 20 (100) |

| Health insurance coverage, n (%) | 20 (100) |

| Body mass index, yr, mean (SD) | 32.25 (6.77) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 17 (85) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 5 (25) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 10 (50) |

| VR familiarity, n (%) | 13 (65) |

| VR experience, n (%) | 6 (30) |

VR, virtual reality.

Recruitment and Feasibility

Figure 2 provides a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram summarizing rates of recruitment, enrollment, and dropout. A total of 29 patients on HD were assessed for eligibility and eight were excluded for the following reasons: (1) self-reported history of epilepsy, seizures, or vertigo (n=3); (2) HD treatment initiated <3 months ago (n=1); and (3) lack of interest in study participation (n=4). Final participant enrollment included 21 patients. However, one participant did not experience the VR program due to the lack of adherence with their scheduled HD treatments. Of the remaining participants, 100% completed both VR exposures.

VR Program Safety

Table 3 summarizes cybersickness scores before and after the two exposures to the VR program. Significant decreases were observed during exposure one for fatigue, nausea, oculomotor symptoms, disorientation, and total symptomology before versus after VR, P<0.05. No statistically significant differences in scores were observed during exposure two.

Table 3.

Safety of the virtual reality program, as measured by changes in Simulator Sickness Questionnaire values pre- to postexposure

| Symptomatology | Exposure One | Exposure Two | ||||

| Pre Virtual Reality, Mean (SD) | Post Virtual Reality, Mean (SD) | P a | Pre Virtual Reality, Mean (SD) | Post Virtual Reality, Mean (SD) | P a a | |

| General discomfort | 7.70 (10.35) | 4.28 (7.61) | 0.16 | 5.99 (11.48) | 3.32 (8.60) | 0.24 |

| Fatigue | 5.31 (6.07) | 1.14 (2.78) | 0.002 | 3.41 (5.75) | 2.65 (5.08) | 0.43 |

| Headache | 1.52 (3.97) | 0.38 (1.69) | 0.27 | 0.76 (2.33) | 0.38 (1.69) | 0.33 |

| Eye strain | 2.27 (4.33) | 2.27 (4.98) | 1.0 | 1.90 (4.17) | 1.14 (2.78) | 0.43 |

| Difficulty focusing | 6.45 (12.28) | 7.53 (12.62) | 0.58 | 5.38 (11.83) | 2.15 (6.62) | 0.27 |

| Salivation increasing | 0.95 (4.27) | 0.95 (4.27) | 0.48 (2.13) | 0.95 (2.94) | 0.33 | |

| Sweating | 2.39 (5.25) | 0.48 (2.13) | 0.10 | 0.95 (2.94) | 0.95 (4.27) | 1.0 |

| Nausea | 8.21 (15.74) | 1.17 (5.25) | 0.06 | 2.35 (7.22) | 0.95 (4.27) | 0.25 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 5.14 (9.78) | 0.86 (3.83) | 0.06 | 2.57 (6.27) | 0.86 (3.83) | 0.16 |

| Fullness of the head | 2.78 (7.28) | 0.70 (3.11) | 0.19 | 1.38 (4.28) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 |

| Blurred vision | 6.45 (12.28) | 6.45 (12.28) | 1.0 | 3.23 (7.88) | 3.23 (7.88) | 1.0 |

| Dizziness w/eyes open | 2.09 (6.82) | 1.39 (6.23) | 0.33 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.0 |

| Dizziness w/eyes closed | 1.39 (6.23) | 1.39 (6.23) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.0 | |

| Vertigob | 2.09 (6.81) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.19 | 0.70 (3.11) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.33 |

| Stomach awarenessc | 2.86 (5.45) | 0.95 (2.94) | 0.10 | 0.48 (2.13) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.33 |

| Burping | 1.91 (4.99) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.10 | 0.48 (2.13) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.33 |

| Subscales and total score | ||||||

| Nausea | 18.60 (30.71) | 5.72 (8.42) | 0.04 | 8.12 (12.49) | 5.25 (15.31) | 0.37 |

| Oculomotor | 19.33 (25.38) | 10.99 (13.35) | 0.03 | 12.89 (20.44) | 7.96 (14.85) | 0.18 |

| Disorientation | 21.58 (44.36) | 13.22 (26.13) | 0.10 | 9.05 (15.16) | 4.87 (11.31) | 0.21 |

| Total Symptom Score | 22.63 (34.71) | 11.22 (15.16) | 0.03 | 11.97 (17.61) | 7.29 (15.28) | 0.18 |

Results of paired sample t tests between pre- and postexposure, P values <0.05, and associated exposure values displayed in bold.

Vertigo is experienced as loss of orientation with respect to vertical upright.

Stomach awareness is usually used to indicate a feeling of discomfort that is just short of nausea.

VR Program Presence and Utility

Table 4 shows the degree to which participants were immersed in the two VR program exposures. Overall presence scores were moderate for both exposures with means around 4.0 (ranging from 1=low to 7=high). Levels varied between more specific measures. Scores were highest for the single measure of presence (“sense of being there”) and lowest for involvement and experience. No scores showed statistically significant differences between exposures one and two, P>0.05. The VR device and software had moderately high levels of usability (see Table 3). The average usability score was 82.74±21.85, and the range was 15–100.

Table 4.

Level of presence during the virtual reality program (n=20)

| Survey Measures | Exposure One, Mean (SD) | Exposure Two, Mean (SD) |

| IPQ | ||

| Overall IPQ Score | 4.13 (1.19) | 3.94 (1.15) |

| General “sense of being there” | 5.60 (1.76) | 4.65 (2.11) |

| Spatial presence | 5.03 (1.53) | 4.57 (1.39) |

| Involvement | 3.30 (1.18) | 3.51 (1.23) |

| Experienced realism | 3.48 (1.62) | 3.39 (1.33) |

| SUS | ||

| Total score | 82.75 (21.85) | |

IPQ, iGroup Presence Questionnaire; SUS, System Usability Scale.

Qualitative Feedback and Clinical Assessments

HD end-users judged the program as fun and easy to use. Specific themes in their responses involved the relaxing/calming environment, effective tool for active distraction, pleasant scenery, and valuable mindfulness education. In terms of recommended improvements, end-users wanted multiple destinations of travel during curricular content and meditation practice, and graphics that more realistically mimic the real world, such as 360° videos of actual locations in the United States and abroad. Staff members reported that the VR program did not interfere with their typical duties (n=8, 100%), did not lead to social isolationism for HD end users (n=8, 100%), and was well received by both patients and clinical staff (n=8, 100%) (Supplemental Appendix A and B).

Effect Modifiers

Table 5 presents the results of stratified analyses by participant subgroups. Mean changes in cybersickness scores did not show significant differences by sex, age, race/ethnicity, or previous VR experience. However, we did observe trends suggesting greater symptom declines in females, Black patients, younger adults (<55), and those with previous VR experience; these differences were most prominent at exposure one. No statistically significant differences were evident in presence and usability by sex, age, or previous VR experience. Nevertheless, trends suggest greater immersion in males and older adults (≥55 years) and greater system usability in non-Hispanic Whites.

Table 5.

Virtual reality assessments stratified by sex, age, and previous virtual reality experience

| Individual-level Characteristics | Simulator Sickness Questionnaire | iGroup Presence Questionnaire | System Usability Scale Postintervention Mean (SD) | ||

| Exposure One Δμ (SD) | Exposure Two Δμ (SD) | Exposure One Mean (SD) | Exposure Two Mean (SD) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | −8.64 (21.06) | −4.91 (11.96) | 4.31 (1.11) | 3.94 (1.14) | 82.81 (22.89) |

| Female | −22.44 (21.81) | −3.74 (27.14) | 3.43 (1.39) | 3.92 (1.39) | 82.50 (20.10) |

| P value | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | −7.48 (9.38) | −2.34 (14.27) | 4.36 (1.10) | 3.73 (1.14) | 90.31 (13.66) |

| Black | −14.03 (26.74) | −6.23 (16.13) | 3.98 (1.26) | 4.07 (1.19) | 77.71 (25.24) |

| P value | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.22 |

| Age | |||||

| <55 | −16.21 (27.55) | −6.23 (16.09) | 3.67 (1.45) | 3.75 (1.48) | 83.89 (17.90) |

| ≥55 | −7.48 (14.96) | −3.40 (15.0) | 4.51 (0.81) | 4.01 (0.85) | 81.82 (25.47) |

| P value | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Previous VR experience | |||||

| Yes | −16.83 (32.15) | −5.61 (16.00) | 3.80 (0.87) | 3.83 (0.76) | 83.33 (21.72) |

| No | −9.08 (15.85) | −4.27 (15.38) | 4.28 (1.30) | 4.0 (1.31) | 82.50 (22.72) |

| P value | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.42 | 0.80 | 0.94 |

Δμ, mean change before versus after virtual reality exposure; VR, virtual reality.

Discussion

We present the first safety test of VR in patients on HD. Our new 25-minute VR program, Joviality, was both safe and enjoyable among HD end-users when delivered chairside. As such, VR may offer a viable high-tech platform to deliver therapies to patients on HD as they attend regularly scheduled dialysis treatment. Further, this VR program decreased HD patient-related symptomatology (e.g., nausea) and elicited high levels of immersion with technology that was easy to operate. These results promote larger trials that focus on the additional benefits of VR for patients on HD including effects on quality of life, dietary adherence, morbidity, and longevity.

The mechanism through which chairside VR exposure might ameliorate HD-related side effects remains unclear. Researchers in the field of pain management suggest two plausible mechanisms are involved: (1) active distraction or attentional diversion, and/or (2) physiologic changes (29). Through its high-definition graphics and interaction with virtual objects, VR can be an effective tool in distracting patients on HD from uncomfortable medical procedures occurring chairside. The stimulus diverts focus away from usual side effects, thereby making symptoms such as nausea and lightheadedness less intense. Alternatively, VR may reduce brain activity in regions where pain responses have been recorded.

If the therapeutic use of VR becomes adopted in HD settings, important questions remain to be answered for optimal efficacy. For example, when is VR exposure most effective during dialysis sessions—the beginning, middle, or toward the end? Also, what types of environmental simulations are most aesthetically pleasing and result in greatest immersion and engagement (e.g., 360° videos or three-dimensional computer animations)? The VR content should also be carefully considered. In its current iteration, our Joviality program is geared toward teaching skills of mindfulness to improve emotional wellbeing, but health education and other public health content could be similarly disseminated. For instance, our group is designing a three-dimensional grocery store tour where patients on HD engage in virtual shopping to identify the types of food that are healthiest to purchase and consume.

Ethical considerations must also be at the forefront of therapeutic uses of VR in HD settings. Kellmeyer et al. (30) provide an insightful commentary on ethical priorities to consider when including VR as a medical technology in therapy. One such ethical dilemma involves the concept of “persuasive technology.” This occurs when VR is the only viable option to escape one’s immediate physical surroundings and when it becomes the main tool to socialize and communicate with others. This is particularly true for patients with paralysis who are “locked in” and their autonomy stripped, thus making human-to-human contact unlikely. For patients on HD, a patient-centered design (31) could be used, whereby VR exposure does not promote social isolation, and sedentarism is not heightened to overcome this dilemma. Results of this study should be interpreted in light of existing limitations. First, we had a limited sample size, with recruitment from a single clinic site in a small college town in the Midwestern United States. Future studies should be conducted in metropolitan cities, with greater diversity in race/ethnicity, place of nativity status, and sex. Second, given the pilot nature of our trial, we did not include a control arm. This precludes us from making causal inferences because improvements in symptoms may have been a result of confounding factors, such as social contact with research staff. A randomized trial that includes an adequate control arm would more clearly elucidate the benefits reported here. Future trials should also adhere to more stringent standardization protocols when timing VR exposure during maintenance HD to test for moderation by dialyzing time. Further, we did not assess for long-term effects of VR exposure on HD-related symptoms. Future trials will want to include multiple prospective waves of data collection. Medical history should also be ascertained through more objective methods in the future, such as adjudication of medical records to avoid recall bias from self-reported data.

This study also had several strengths. This trial was the first to test whether VR is safe for chairside use with patients on HD. We did not use commercialized VR content but instead designed a new program tailored for HD end-users. The VR program content was adapted from the evidenced-based positive psychologic intervention DAHLIA (18). And we limited VR intractability to head movement, given limited hand mobility of patients on HD during dialysis. Commercial VR programs often utilize remote controllers to move within a virtual space, which would not have been practical for many HD end-users. In light of these strengths, we hope to conduct additional trials with adapted versions of Joviality in the near future. End-users will encounter a different setting and curricular module at each immersion. New weekly content will counter study findings where improvements were most prominent at exposure one. (It is possible that end-users became familiar with the content when an identical lesson was delivered in the same location.) As in the gaming industry, creation of new content will likely prove critical. We will also test whether VR exposure leads to carryover effects where symptom improvement is sustained, and whether timing of VR exposure serves as an effect modifier.

In conclusion, this pilot trial provides promising findings regarding the safety and benefit of VR for patients on HD. Future trials to more robustly test efficacy are now called for, and are indeed underway.

Disclosures

K.R. Wilund reports receiving honoraria from the Greenfield Health Systems, National Kidney Foundation, and Renal Research Institute, Inc.; reports being a scientific advisor or member of the Journal of Renal Nutrition; and reports having other interests/relationships in the Kidney Health Initiative. R. Hernandez reports being a scientific advisor or member of the American Heart Association, Nazareth Academy. All remaining authors have nothing to declare.

Funding

R. Hernandez is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through award 1K01HL130712-01A5. Additionally, research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Campus Research Board grant RB19034, VR@Illinois, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award U54MD012523.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of clinical staff of the hemodialysis enrollment site, along with all participants who graciously allowed us to collect their data and qualitative experience with our software. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions

B. Burrows was responsible for project administration; B. Burrows and R. Hernandez were responsible for formal analysis; M. Browning, D. Fast, R. Hernandez, N. Litbarg, J. Moskowitz, K. Solai, and K. Wilund were responsible for methodology; D. Fast, N. Litbarg, J. Moskowitz, K. Solai, and K. Wilund were responsible for resources; R. Hernandez, J. Moskowitz, and K. Wilund conceptualized the study and were responsible for funding acquisition; R. Hernandez, N. Litbarg, and J. Moskowitz were responsible for investigation; R. Hernandez, K. Solai, and K. Wilund provided supervision; M. Browning and R. Hernandez wrote the original draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at http://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0005522020/-/DCSupplemental.

Postintervention clinical staff feedback (n=8). Download Supplemental Appendix A, DOCX file, 14 KB (13.1KB, docx)

Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). Download Supplemental Appendix B, DOCX file, 14 KB (13.1KB, docx)

References

- 1.LaValle SM: Virtual Reality, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017, 418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghanbarzadeh R, Ghapanchi AH, Blumenstein M, Talaei-Khoei A: A decade of research on the use of three-dimensional virtual worlds in health care: A systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res 16: e47, 2014. 10.2196/jmir.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindner P, Miloff A, Zetterlund E, Reuterskiöld L, Andersson G, Carlbring P: Attitudes toward and familiarity with virtual reality therapy among practicing cognitive behavior therapists: A cross-sectional survey study in the era of consumer VR platforms. Front Psychol 10: 176, 2019. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motraghi TE, Seim RW, Meyer EC, Morissette SB: Virtual reality exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A methodological review using CONSORT guidelines. J Clin Psychol 70: 197–208, 2014. 10.1002/jclp.22051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indovina P, Barone D, Gallo L, Chirico A, De Pietro G, Giordano A: Virtual reality as a distraction intervention to relieve pain and distress during medical procedures: A comprehensive literature review. Clin J Pain 34: 858–877, 2018. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerdan SW, Grindle M, van Woerden HC, Kamel Boulos MN: Head-mounted virtual reality and mental health: Critical review of current research. JMIR Serious Games 6: e14, 2018. 10.2196/games.9226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishkind MC, Norr AM, Katz AC, Reger GM: Review of virtual reality treatment in psychiatry: Evidence versus current diffusion and use. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19: 80, 2017. 10.1007/s11920-017-0836-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dascal J, Reid M, IsHak WW, Spiegel B, Recacho J, Rosen B, Danovitch I: Virtual reality and medical inpatients: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Innov Clin Neurosci 14: 14–21, 2017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malloy KM, Milling LS: The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 30: 1011–1018, 2010. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho H, Sohng K-Y: The effect of a virtual reality exercise program on physical fitness, body composition, and fatigue in hemodialysis patients. J Phys Ther Sci 26: 1661–1665, 2014. 10.1589/jpts.26.1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segura‐Ortí E, García‐Testal A: Intradialytic virtual reality exercise: Increasing physical activity through technology. Semin Dial 32: 331–335, 2019. 10.1111/sdi.12788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou H-Y, Chen S-C, Yen T-H, Han H-M: Effect of a virtual reality-based exercise program on fatigue in hospitalized Taiwanese end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clin Nurs Res 29: 368–374, 2020. 10.1177/1054773818788511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Nazly E, Ahmad M, Musil C, Nabolsi M: Hemodialysis stressors and coping strategies among Jordanian patients on hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Nephrol Nurs J 40: 321–327; quiz 328, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahaf R, Sadat Ilali E, Peyrovi H, Akbari Kamrani AA, Spahbodi F: Uncertainty, the overbearing lived experience of the elderly people undergoing hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 5: 13–21, 2017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabat-Zin J: Full Catastrophe Living: Usingthe Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness, New York, Random House Publishing Group, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber SM, Jeitziner MM, Wyss P, Chesham A, Urwyler P, Müri RM, Jakob SM, Nef T: Visuo-acoustic stimulation that helps you to relax: A virtual reality setup for patients in the intensive care unit. Sci Rep 7: 13228, 2017. 10.1038/s41598-017-13153-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeiffer E: A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 23: 433–441, 1975. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, Hult JR, Moskowitz JT: An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Posit Psychol 9: 523–534, 2014. 10.1080/17439760.2014.920410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen D, Lindvall M, Costa P: An introduction to agile methods. Adv Comput 62: 1–66, 2004. 10.1016/S0065-2458(03)62001-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaphiris P, Ioannou A: Learning and Collaboration Technologies. Second International Conference, LCT 2015, Held as Part of HCI International 2015, Los Angeles, CA, USA, August 2–7, 2015. 10.1007/978-3-319-20609-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy RS, Lane NE, Berbaum KS, Lilienthal MG: Simulator sickness questionnaire: An enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int J Aviat Psychol 3: 203–220, 1993. 10.1207/s15327108ijap0303_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schubert T, Friedmann F, Regenbrecht H: The experience of presence: Factor analytic insights. Presence (Camb Mass) 10: 266–281, 2001. 10.1162/105474601300343603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Constantin C, Grigorovici D: Virtual Environments and the Sense of Being There: An SEM Model of Presence. in Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Workshop on Presence, Aalborg University, Denmark, October 6-8, 2003.

- 24.Schwind V, Knierim P, Haas N, Henze N: Using presence questionnaires in virtual reality. in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, May 4–9, 2019 10.1145/3290605.3300590 [DOI]

- 25.Brooke J: System Usability Scale, Reading, England, Digital Equipment Corporation, 1986, p 480 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooke J: SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. In: Usability Evaluation in Industry, edited by Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland AL, London, Taylor and Francis, 1996, pp 189–194 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauro J: Measuring Usability with the System Usability Scale, SUS, 2011. Available at: https://measuringu.com/sus/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirico A, Gaggioli A: When virtual feels real: Comparing emotional responses and presence in virtual and natural environments. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22: 220–226, 2019. 10.1089/cyber.2018.0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta A, Scott K, Dukewich M: Innovative technology using virtual reality in the treatment of pain: Does it reduce pain via distraction, or is there more to it? Pain Med 19: 151–159, 2018. 10.1093/pm/pnx109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellmeyer P, Biller-Andorno N, Meynen G: Ethical tensions of virtual reality treatment in vulnerable patients. Nat Med 25: 1185–1188, 2019. 10.1038/s41591-019-0543-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triberti S, Liberati EG: In: Virtual Reality: Technologies, Medical Applications and Challenges, edited by Cipresso P, Serino S, Hauppauge, NY, Nova Science, 2015, pp 3–30 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Postintervention clinical staff feedback (n=8). Download Supplemental Appendix A, DOCX file, 14 KB (13.1KB, docx)

Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). Download Supplemental Appendix B, DOCX file, 14 KB (13.1KB, docx)