Abstract

The adequacy of hemodialysis is now assessed by measuring the removal of a single solute, urea. The urea clearance provided by current dialysis methods is a large fraction of the blood flow through the dialyzer, and, therefore, cannot be increased much further. However, other solutes, which are less effectively cleared than urea, may contribute more to the residual uremic illness suffered by patients on hemodialysis. Here, we review a variety of methods that could be used to increase the clearance of such nonurea solutes. New clinical studies will be required to test the extent to which increasing solute clearances improves patients’ health.

Keywords: dialysis, blood urea nitrogen, hemodialysis adequacy, hemodynamics, renal dialysis

Introduction

We presume that an important part of the residual illness in patients maintained on hemodialysis is due to incomplete removal of uremic solutes (1–4). The variety of such solutes is enormous (5), yet we now assess the adequacy of treatment by the removal of a single solute, urea. This review will describe potential means to improve clearance of nonurea solutes using mechanical devices. We will not discuss peritoneal dialysis, and will deal only in passing with solute properties that prevent increases in their clearance from achieving proportional reductions in their plasma levels. We will separately consider the clearances of free low mol wt solutes, middle molecules, and protein-bound solutes. To do so, we use the classification originally proposed by the European Uremic Toxin Work Group, which was founded in 1999 to address question related to solute retention and removal in CKD (2,5,6).

Free Low Mol Wt Uremic Solutes

Urea has served as a prototype for free, low mol wt uremic solutes. Its use for assessing treatment adequacy has directed the design of dialyzers and dialysis machines. With conventional hemodialysis, a large portion of the urea is cleared from the blood on a single pass through the dialyzer. The urea clearance cannot be increased much further by increasing the dialyzer membrane capacity or dialysate flow (7,8). The case is different, however, for nonurea solutes. Membrane capacity, as assessed by the mass transfer area coefficient KoA, declines in approximate proportion to the square root of the solute mass (9). A dialyzer’s KoA for solutes with a mass of 240 D is thus approximately half that of its KoA for urea, with a mass of 60 D. Viscosity further lowers the effective KoA of a dialyzer for removal of solutes from plasma, as compared with aqueous solutions (9). Therefore, the predicted clearances of free solutes decline with increasing mass, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The increase in clearance provided by an increase in KoA is relatively greater for solutes of larger size. The solid line depicts clearance values obtained with a standard dialyzer with the mass transfer area coefficient of urea (KoAurea) of 1400 ml/min in an aqueous solution, as assessed by the manufacturer. The dashed line depicts clearance values obtained with a dialyzer with a KoAurea twice as high. KoA values in plasma were reduced by a factor of 0.52, as compared with the KoA in aqueous solution, and KoA was assumed to decrease in the proportion m−0.46, where m is the solute molecular mass as described by Schneditz and Daugirdas (9). Clearance values were modeled for a plasma flow of 250 ml/min and a dialysate flow of 600 ml/min, using a published model (10). Doubling KoA has little effect on the clearance of very small solutes, but a larger effect on the clearance solutes with a molecular mass in the range of 400–2000 D. The clearance of such solutes, which includes the lower end of the range now classified as “middle molecules,” could be increased simply by increasing the size of dialyzers made with current membrane materials. The addition of convection, which is now used to increase the clearance of low molecular mass proteins, such as β2 microglobulin which has a molecular mass of approximately 12,000 D, would not be required.

Because toxicities have not been proven for solutes in the mass range depicted in Figure 1, there has been limited effort to increase their clearances. Here we encounter a recurrent problem in dialysis research that is reminiscent of the conundrum which gave the novel Catch 22 its title. We cannot prove that solutes are toxic without lowering their levels, and we do not develop means to lower their levels without proof they are toxic. However, the hope that dialysis can be miniaturized for ambulatory treatment has stimulated the development of new membrane materials (11). Such materials could allow dialyzer KoA values to be greatly increased, without increasing dialyzer size.

Middle Molecules

Early dialysis membranes were impermeable to solutes with a molecular mass much greater than 400 D. Dialysis with these membranes reversed uremic coma and kept patients alive for years. Researchers hypothesized, however, that removal of larger solutes would improve health. It was initially suggested that toxic, larger solutes had molecular masses in the range of between 300 and 2000 D, and they were thus designated “middle molecules.” (12) The meaning of “middle molecules” has changed over time to include solutes with molecular masses of between 600 and 45,000 D. Most of these molecules are small proteins with molecular masses >10,000 D (2). Efforts to increase the clearance of such solutes were stimulated by the finding that accumulation of β2 microglobulin caused amyloidosis in patients on dialysis. β2 Microglobulin, with a molecular mass of 12,000 D, was adopted as a prototypic middle molecule, just as urea had been adopted as a prototypic free, low mol wt solute.

The clearance of solutes in the size range of β2 microglobulin was initially increased by making dialysis membranes permeable to larger solutes. Use of these “high-flux” membranes provided β2 microglobulin clearances in the range of 20 ml/min. The Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study failed to show clear benefit from increasing β2 microglobulin clearance to this level, as compared with the few milliliters per minute achieved with “low-flux” membranes (13). However, researchers responded to this failure differently than to HEMO’s failure to show benefit with increased clearance of urea. Efforts were made to further increase the clearance of low mol wt proteins. Rapid passage of blood through the dialyzer does not allow sufficient time for large molecules to be cleared by diffusion, even if the dialysis membrane is permeable to them. However, their clearance can be increased by hemodiafiltration, which adds convective clearance to dialytic clearance. Convective clearance can also be added to dialytic clearance by manipulating blood and dialysate pressures within a dialysis cartridge (14,15).

Increasing β2 microglobulin clearances to approximately 80 ml/min by hemodiafiltration has, so far, failed to clearly improve outcomes in patients enrolled in clinical trials (16). Proponents of the technique note that patients who have achieved the highest ultrafiltration volumes have appeared to benefit (17,18). A randomized trial is now being conducted to more rigorously test the benefit of high-volume ultrafiltration (19). Efforts to further increase the clearance of middle molecules are also ongoing. Some efforts have been made to increase the clearance of β2 microglobulin and other low mol wt proteins by passing blood over sorbent columns (20). Currently, such protein sorbent columns are being considered largely for treatment of sepsis and associated acute kidney insufficiency (21). Other efforts are directed toward increasing the clearance of low mol wt proteins that are larger than β2 microglobulin. New dialyzers can clear such solutes by using “medium-cutoff” membranes that are permeable to solutes with a molecular mass up to 50 kD combined with designs promoting internal convection (22).

Our ability to increase clearances of β2 microglobulin and even larger solutes has revealed a fundamental, pathophysiologic problem. Plasma levels may not fall in proportion to the increase in solute clearances, particularly when treatment is intermittent (23). In the HEMO Study, increasing the average β2 microglobulin clearance by more than five-fold reduced the average plasma level by only 20% (24). This apparent discrepancy may be attributable to two factors (25). First, a low, but continually operating, nonrenal clearance accomplishes a large portion of the removal of β2 microglobulin. Second, β2 microglobulin movement from the interstitium to the plasma is restricted and plasma β2 microglobulin levels rebound after rapid removal from the plasma during intermittent dialysis or hemodiafiltration. It seems likely that these factors also limit the extent to which high renal replacement clearances can lower levels of other middle molecules. It is notable that increasing the clearances of solutes with a molecular mass >20 kD using medium-cutoff membranes has generally failed to lower their plasma levels (26–28). These findings should stimulate further investigation of the largely unknown mechanisms by which low mol wt proteins are cleared outside the kidney at a low rate. We might be able to increase this nonrenal clearance in patients whose kidneys have failed.

Protein-Bound Solutes

The protein-bound solutes are small molecules that bind to plasma proteins, with known examples binding largely to albumin (29–31). Conventional dialysis clears them poorly because only the free portion of the solute contributes to the concentration gradient driving their diffusion from the plasma to the dialysate (32). There has been much less clinical study of increasing the clearance of protein-bound solutes than of increasing the clearance of middle molecules. Looking back, it appears that this may have been because no single bound solute was shown to have a specific ill effect, such as the amyloidosis caused by accumulation of β2 microglobulin.

The clearance of bound solutes can be increased by increasing the free fraction of the solute as blood passes through the dialyzer. One attractive means to accomplish this is by adding displacing agents to the blood entering the dialyzer (33). Madero et al. (34) recently showed that infusion of ibuprofen could significantly increase the clearance of the bound solutes indoxyl sulfate and para-cresol sulfate during single dialysis treatments. Successful chronic treatment will require identification of displacing agents that can be repeatedly administered in sufficient concentrations without ill effect. Alternative agents have been considered but have not yet been shown to satisfy this requirement (35).

Imposing physical-chemical changes could also increase the free fractions of bound solutes as blood passes through the dialyzer. The free fraction of many bound solutes can be increased by lowering the blood pH (36). Clinical testing has been restricted to preventing a rise in blood pH during hemodialysis treatment, rather than lowering the blood pH (37). This had only a limited effect on the clearance of protein-bound uremic solutes, and whether reduction of blood pH below physiologic levels would have a greater effect remains to be tested. Another potential means to increase the free fraction of bound solutes is to increase the tonicity of the blood as it flows through the dialyzer (38). As with changes in pH, large changes in tonicity may be required to increase the free fractions of bound solutes, and the extent to which such changes can be safely imposed remains uncertain. It has also been suggested that the clearance of bound solutes can be increased by the imposition of electrical fields, possibly in conjunction with the use of new composite membrane materials (39,40).

Sorbents provide an alternate means to remove uremic solutes that bind to plasma proteins. Early physicians attempted to clear uremic solutes by direct passage of blood over activated carbon (41). However, contact of blood with carbon caused platelet consumption and other complications (42,43). These complications were largely avoided by coating carbon granules with cellulose acetate or other materials. Since then, hemoperfusion, using coated carbon cartridges, has mainly been used to remove poisons. Cartridges remain available, but evidence for efficacy is lacking and their use has declined where hemodialysis is available (43).

Hemoperfusion over coated sorbent granules provided limited clearance because solutes that diffuse through the coating cannot readily permeate the interior of the granules (44). Several strategies have been envisioned to improve the access of plasma solutes to sorbents (45). The first is to create sorbents that allow direct hemoperfusion by taking up solutes of interest without adversely affecting other blood constituents. Modern materials science provides a variety of means to create such sorbents (46–49). Clinical testing, however, has been limited and the ability to enhance the removal of protein-bound uremic solutes has not been demonstrated (48,49).

A second strategy for sorbent removal of bound solutes is to separate the plasma from the cellular components of the blood using a membrane with a molecular mass cutoff of 250–300 kD. The plasma stream created by this “plasma fractionation” can then be passed over sorbents to remove bound solutes. This strategy was largely developed for the treatment of liver failure, and its effect was measured by removal of bilirubin and bile acids (50). Limited trials showed that it could increase the clearance of protein-bound solutes from patients with ESKD (51,52). However, testing in ESKD was complicated by coagulation abnormalities and was, therefore, abandoned (53).

A third strategy for sorbent removal of bound solutes in hemodialysis is to add a sorbent to the dialysate compartment. This has the effect of reducing the solute concentration in the dialysate compartment toward zero, and thereby increasing the concentration gradient across the dialysis membrane (54). Because the free solute concentration of a highly bound solute in the plasma remains low, a high-capacity membrane is required to achieve high clearances of bound solutes when sorbent is added to the dialysate compartment (32). Indeed, adding a sorbent to the dialysate compartment has the same effect on bound solute clearances as greatly increasing the dialysate flow (54). Pilot clinical studies have shown that the bound solute clearances achieved with conventional hemodialysis can be increased significantly by increasing dialyzer membrane capacity together with dialysate flow (55,56).

An obvious candidate sorbent for addition to the dialysate compartment is albumin. Solutes bound to albumin in a patient’s plasma would pass through the dialysis membrane and be absorbed onto albumin in the dialysate compartment. Two designs for “albumin dialysis” have been considered. In “single-pass albumin dialysis,” the patient is dialyzed against an albumin solution that is discarded after passage over the dialysis membrane. In “sorbent-recirculating dialysis,” the patient is dialyzed against an albumin solution that is then dialyzed against standard dialysate in a second dialyzer, to remove unbound solutes and electrolytes, and is then passed through sorbent cartridges, to remove bound solutes, before being recirculated to dialyze the patient. Similarly to plasma fractionation, albumin dialysis has been developed as a short-term treatment for liver failure (50). Its questionable efficacy and great expense have discouraged consideration of its use as RRT.

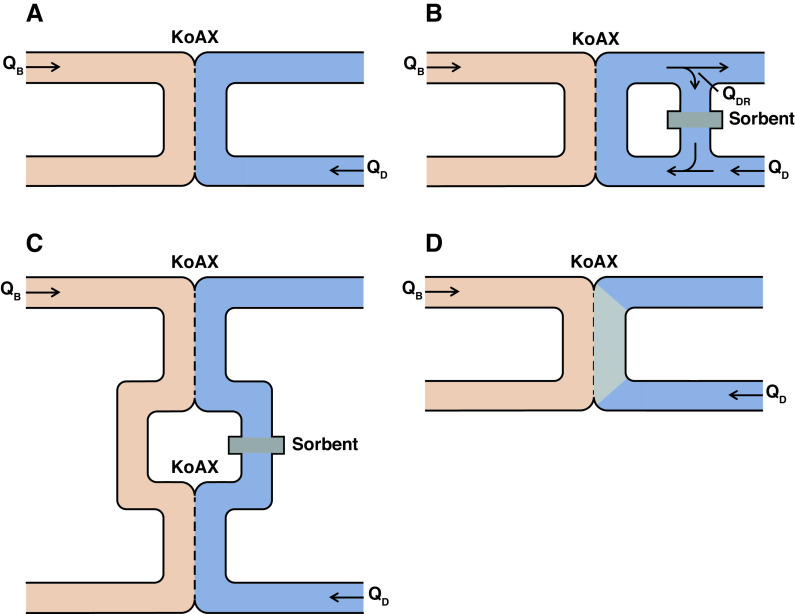

Other sorbents can also be added to the dialysate compartment to increase the diffusive clearance of protein-bound solutes. This has, so far, only been tested in vitro, with activated carbon being the sorbent most frequently used. Various configurations for adding activated carbon to the dialysate stream have been envisioned, as illustrated in Figure 2. Perhaps the simplest design is for a sorbent to be added to the dialysate stream (54). This is equivalent to albumin dialysis, but with the use of a sorbent other than albumin. Alternate designs would fix the sorbent in different positions in the dialysate stream. As is the case with plasma separation, sorbent addition to the dialysate stream has been considered more extensively for the treatment of liver failure than for kidney failure (57). In one design, part of the dialysate stream would be passed over a sorbent and then added to the fresh dialysate being pumped past the dialysis membrane (Figure 2B). The effect would be to greatly increase the effective dialysate flow for solutes taken up by the sorbent, and to increase their clearances by keeping their concentrations low in the dialysate compartment. This design might have particular application in home hemodialysis, in which low dialysate flows are commonly prescribed to limit the cost and complexity of home dialysate production (58). Another design would be to insert a sorbent cartridge in the dialysate path of two dialyzers used in series (Figure 2C). This configuration has the advantage that it could be tested using standard dialyzers and dialysis machines. Perhaps the optimal configuration for adding sorbent to the dialysate compartment would be to fix the sorbent in the dialysate compartment along the length of a dialyzer (Figure 2D). Of note, sorbent fixation to the dialysis membrane was tested early during the development of hemodialysis; however, its effect on bound solute clearances was not evaluated (59–61). The recent development of a mixed-matrix hemodialysis membrane, in which activated carbon is incorporated into the membrane material, represents a technical advance along these lines (62). The performance of mixed-matrix membranes could potentially be enhanced by an “outside-in” design, with dialysate flowing through hollow fibers while blood flows outside the fibers (63).

Figure 2.

Potential configurations for sorbent addition to the dialysate compartment to improve the clearance of protein-bound solutes. (A) In standard hemodialysis without any sorbent, blood (pink) flows at a rate QB past a semipermeable membrane (dashed line) with size KoAx for solute x, with dialysate (blue) flowing at a rate QD in the opposite direction on the other side of the membrane. Uremic solutes (not shown) diffuse from the blood into the dialysate, which goes down the drain. Different configurations for addition of a sorbent to lower the concentrations of bound solutes in the dialytic compartment have been considered. (B) Part of the dialysate stream now is diverted and flows at a rate QDR over a sorbent (gray shaded area), before being reintroduced into the stream of fresh dialysate entering the system at a flow rate of QD. The effective dialysate flow for a given solute is determined by the extent to which the sorbent takes up that solute. (C) Blood passes through two dialyzers in series, and a sorbent cartridge is inserted in the dialysate stream between the two dialyzers. (D) Sorbent material is fixed along the dialysate path within a dialyzer.

Although activated carbon has been the sorbent most commonly considered for addition to the dialysate stream, other materials could provide special benefits or greater safety (46,64–66). Addition of lipids to the dialysate was initially evaluated as a means to improve removal of drugs that bind to both lipids and plasma proteins (67,68). The addition of lipid to the dialysate could potentially increase the clearance of as-yet-unknown uremic toxins that bind to circulating lipids more than to proteins. It has also recently been suggested that liposomes could be added to the dialysate to absorb uremic solutes and thereby increase their dialytic clearance (65).

What Next?

We have means, as described above, to increase the clearances of various types of solutes. However, we have not identified those solutes that are the most toxic and, therefore, the most important to remove. This lack of information is a major impediment to progress. If we knew which solutes were toxic, we could refine our proposed methods for solute clearance. Sorbents that remove specific solutes from the blood or dialysate, displacing agents that release specific solutes from binding proteins, and active membrane materials that selectively pass or chemically degrade specific solutes could be devised. Solutes whose behaviors are not adequately characterized under our current classification scheme may require additional consideration, including solutes that bind to plasma lipids and solutes that move into, or out of, erythrocytes during conventional dialysis (69,70).

Metabolomic studies, using untargeted mass spectrometry, have provided a new means to identify toxic uremic solutes. This analytic method has increased the number of known uremic solutes to >250, and additional solutes continue to be identified (3,71–74). Large-scale studies will be required, however, to associate levels of individual solutes with clinical and physiologic end points. An alternate means to identify toxic solutes is to try to increase the clearance and lower the levels of whole groups of solutes. Positive clinical effects could both improve current treatment and provide direction to our search for specific toxins. Efforts to improve the removal of large middle molecules are ongoing, as described above. Means to improve the removal of protein-bound solutes have been much less extensively tested in patients. A clinical trial of adding activated carbon to the dialysate stream (using the configurations depicted in Figure 2, B or C) might speed progress in this area. Such a trial could be performed with only modest modifications to existing hemodialysis equipment. A positive result would spur development of more effective means to clear bound solutes. A question attracting current clinical interest is the relative value of residual native kidney function to dialysis (75,76). The ratio of residual to dialytic clearance for individual solutes is highly variable (25,77). Better knowledge of the extent to which residual function allows dialysis to be curtailed could help identify the solutes that are most toxic.

Finally, we face the question of the how solute levels respond to changes in their extracorporeal clearances. The failure of β2 microglobulin levels to fall in proportion to increases in the extracorporeal β2 microglobulin clearance has been noted above. Other studies suggest that plasma levels of the commonly studied, bound solute para-cresol sulfate are unaffected by large changes in its time-averaged dialytic clearance (78–81). This phenomenon remains unexplained, but could reflect changes in solute production combined with nonrenal clearance and/or a complex compartmental distribution. A question of particular current interest is the value of continuous clearance supplied by a wearable or implantable dialysis machine (11,82). The value of continuous, as opposed to intermittent, clearance can depend on a solute’s dialytic clearance relative to its volume of distribution within the body, as depicted in Figure 3. Overall, we need more knowledge, not only of solute toxicity, but also of solute generation and disposition within the body to improve our methods for solute removal.

Figure 3.

Predicted plasma solute levels with continuous dialysis using a wearable dialyzer (blue lines) compared with 8 hours of nocturnal dialysis, providing 10-fold higher solute clearances (red lines, with time averaged concentrations as dashed lines). Levels are depicted over the course of 24 hours for urea and two solutes that are normally cleared by tubular secretion. Solute A is not protein bound and is normally cleared at 540 ml/min by the kidneys, with a volume of distribution of 14 L. Solute B is normally 98% bound and has a kidney clearance of 23 ml/min and a volume of distribution of 13 L in terms of its total plasma levels. The figure is scaled so that plasma free levels would be 1.0 for each solute in humans with normal kidney function. The continuously operating wearable dialyzer provides a urea clearance of 17 ml/min, equal to that of the device described by Gura et al. (83). Dialytic clearances of the secreted solutes are adjusted downward, relative to urea, to 10 ml/min for the unbound solute and 1.3 ml/min for the bound solute, on the basis of the dialytic clearances of phenylacetylglutamine and para-cresol sulfate observed by Sirich et al. (84). The figure shows that plasma levels of solutes normally cleared by secretion are poorly controlled by dialysis, whether it is provided continuously or intermittently. Levels of urea are maintained within four-fold of normal by both treatments and must be plotted on an expanded scale for their diurnal variation be apparent, whereas levels of the secreted solutes remain >20-fold above normal. Compared with continuous dialysis, a higher clearance during nocturnal treatment can control average solute levels, but will allow wide diurnal variation in the levels of those solutes for which the dialytic clearance is high relative to their volume of distribution. The control of a solute’s plasma level with continuous dialysis, compared with intermittent dialysis, is highly dependent on the solute’s volume of distribution and compartmental behavior.

Disclosures

T. W. Meyer reports having consultancy agreements with, and receiving honoraria from, Baxter; serving on the editorial board for JASN and Kidney International; receiving research funding from Outset Medical; and having a patent application pending for improved removal of protein-bound solutes by dialysis. T. L. Sirich reports having consultancy agreements with Baxter. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

S. Lee was supported by the American Society of Nephrology Ben J Lipps Research Fellowship.

T. W Meyer was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant R01 DK101674. T. L. Sirich was supported by NIDDK grant R01 DK118426.

Author Contributions

S. Lee, T. W. Meyer, and T. L. Sirich wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Depner TA: Uremic toxicity: Urea and beyond. Semin Dial 14: 246–251, 2001. 10.1046/j.1525-139X.2001.00072.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duranton F, Cohen G, De Smet R, Rodriguez M, Jankowski J, Vanholder R, Argiles A; European Uremic Toxin Work Group: Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1258–1270, 2012. 10.1681/ASN.2011121175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka H, Sirich TL, Plummer NS, Weaver DS, Meyer TW: An enlarged profile of uremic solutes. PLoS One 10: e0135657, 2015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee EP, Waikar SS, Rebholz CM, Zheng Z, Perichon R, Clish CB, Evans AM, Avila J, Denburg MR, Anderson AH, Vasan RS, Feldman HI, Kimmel PL, Coresh J; CKD Biomarkers Consortium: Variability of two metabolomic platforms in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 40–48, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.07070618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanholder R, De Smet R, Glorieux G, Argiles A, Baurmeister U, Brunet P, Clark W, Cohen G, De Deyn PP, Deppisch R, Descamps-Latscha B, Henle T, Jorres A, Lemke HD, Massy ZA, Passlick-Deetjen J, Rodriguez M, Stegmayr B, Stenvinkel P, Tetta C, Wanner C, Zidek W: Review on uremic toxins: Classification, concentration, and interindividual variability [published correction appears in Kidney Int 98: 1354, 2020 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.001]. Kidney Int 63: 1934–1943, 2003. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00924.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanholder R, Abou-Deif O, Argiles A, Baurmeister U, Beige J, Brouckaert P, Brunet P, Cohen G, De Deyn PP, Drüeke TB, Fliser D, Glorieux G, Herget-Rosenthal S, Hörl WH, Jankowski J, Jörres A, Massy ZA, Mischak H, Perna AF, Rodriguez-Portillo JM, Spasovski G, Stegmayr BG, Stenvinkel P, Thornalley PJ, Wanner C, Wiecek A: The role of EUTox in uremic toxin research. Semin Dial 22: 323–328, 2009. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depner TA: Prescribing Hemodialysis: A Guide to Urea Modeling, 2nd Ed., Norwall, MA, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhimani JP, Ouseph R, Ward RA: Effect of increasing dialysate flow rate on diffusive mass transfer of urea, phosphate and beta2-microglobulin during clinical haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3990–3995, 2010. 10.1093/ndt/gfq326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneditz D, Daugirdas JT: Quantifying the effect of plasma viscosity on in vivo dialyzer performance. ASAIO J 66: 834–840, 2020. 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walther JL, Bartlett DW, Chew W, Robertson CR, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Downloadable computer models for renal replacement therapy. Kidney International 69: 1056–1063, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hojs N, Fissell WH, Roy S: Ambulatory hemodialysis-technology landscape and potential for patient-centered treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 152–159, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.01970219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scribner BH, Babb AL: Evidence for toxins of “middle” molecular weight. Kidney Int Suppl (3): 349–351, 1975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Cheung AK, Daugirdas JT, Greene T, Kusek JW, Allon M, Bailey J, Delmez JA, Depner TA, Dwyer JT, Levey AS, Levin NW, Milford E, Ornt DB, Rocco MV, Schulman G, Schwab SJ, Teehan BP, Toto R; Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study Group: Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 347: 2010–2019, 2002. 10.1056/NEJMoa021583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieter DH, Falkenhain S, Chalabi L, Collins G, Lemke HD, Canaud B: Clinical cross-over comparison of mid-dilution hemodiafiltration using a novel dialyzer concept and post-dilution hemodiafiltration. Kidney Int 67: 349–356, 2005. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoro A, Ferramosca E, Mancini E, Monari C, Varasani M, Sereni L, Wratten M: Reverse mid-dilution: New way to remove small and middle molecules as well as phosphate with high intrafilter convective clearance. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 2000–2005, 2007. 10.1093/ndt/gfm101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang AY, Ninomiya T, Al-Kahwa A, Perkovic V, Gallagher MP, Hawley C, Jardine MJ: Effect of hemodiafiltration or hemofiltration compared with hemodialysis on mortality and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 968–978, 2014. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blankestijn PJ, Grooteman MP, Nube MJ, Bots ML: Clinical evidence on haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33[suppl_3]: iii53–iii58, 2018. 10.1093/ndt/gfy218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canaud B, Köhler K, Sichart JM, Möller S: Global prevalent use, trends and practices in haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 398–407, 2020. 10.1093/ndt/gfz005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blankestijn PJ, Fischer KI, Barth C, Cromm K, Canaud B, Davenport A, Grobbee DE, Hegbrant J, Roes KC, Rose M, Strippoli GF, Vernooij RW, Woodward M, de Wit GA, Bots ML: Benefits and harms of high-dose haemodiafiltration versus high-flux haemodialysis: The comparison of high-dose haemodiafiltration with high-flux haemodialysis (CONVINCE) trial protocol. BMJ Open 10: e033228, 2020. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morena MD, Guo D, Balakrishnan VS, Brady JA, Winchester JF, Jaber BL: Effect of a novel adsorbent on cytokine responsiveness to uremic plasma. Kidney Int 63: 1150–1154, 2003. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girardot T, Schneider A, Rimmelé T: Blood purification techniques for sepsis and septic AKI. Semin Nephrol 39: 505–514, 2019. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2019.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch AH, Lyko R, Nilsson LG, Beck W, Amdahl M, Lechner P, Schneider A, Wanner C, Rosenkranz AR, Krieter DH: Performance of hemodialysis with novel medium cut-off dialyzers. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 165–172, 2017. 10.1093/ndt/gfw310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirich TL: Obstacles to reducing plasma levels of uremic solutes by hemodialysis. Semin Dial 30: 403–408, 2017. 10.1111/sdi.12609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung AK, Rocco MV, Yan G, Leypoldt JK, Levin NW, Greene T, Agodoa L, Bailey J, Beck GJ, Clark W, Levey AS, Ornt DB, Schulman G, Schwab S, Teehan B, Eknoyan G: Serum beta-2 microglobulin levels predict mortality in dialysis patients: Results of the HEMO study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 546–555, 2006. 10.1681/ASN.2005020132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward RA, Greene T, Hartmann B, Samtleben W: Resistance to intercompartmental mass transfer limits beta2-microglobulin removal by post-dilution hemodiafiltration. Kidney Int 69: 1431–1437, 2006. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belmouaz M, Diolez J, Bauwens M, Duthe F, Ecotiere L, Desport E, Bridoux F: Comparison of hemodialysis with medium cut-off dialyzer and on-line hemodiafiltration on the removal of small and middle-sized molecules. Clin NephrolClin Nephrol 89: 50–56, 2018. 10.5414/CN109133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho NJ, Park S, Islam MI, Song HY, Lee EY, Gil HW: Long-term effect of medium cut-off dialyzer on middle uremic toxins and cell-free hemoglobin. PLoS One 14: e0220448, 2019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner DE, Falzon L, Skoufos L, Bernardo A, Beck W, Xiao M, Tran H: Efficacy and safety of expanded hemodialysis with the Theranova 400 Dialyzer: A randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1310–1319, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.01210120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viaene L, Annaert P, de Loor H, Poesen R, Evenepoel P, Meijers B: Albumin is the main plasma binding protein for indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate. Biopharm Drug Dispos 34: 165–175, 2013. 10.1002/bdd.1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niwa T: Removal of protein-bound uraemic toxins by haemodialysis. Blood Purif 35[Suppl 2]: 20–25, 2013. 10.1159/000350843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neirynck N, Glorieux G, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Dhondt A, Vanholder R: Review of protein-bound toxins, possibility for blood purification therapy. Blood Purif 35[Suppl 1]: 45–50, 2013. 10.1159/000346223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer TW, Leeper EC, Bartlett DW, Depner TA, Lit YZ, Robertson CR, Hostetter TH: Increasing dialysate flow and dialyzer mass transfer area coefficient to increase the clearance of protein-bound solutes. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1927–1935, 2004. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000131521.62256.F0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao X, Thijssen S, Kotanko P, Ho CH, Henrie M, Stroup E, Handelman G: Improved dialytic removal of protein-bound uraemic toxins with use of albumin binding competitors: An in vitro human whole blood study. Sci Rep 6: 23389, 2016. 10.1038/srep23389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madero M, Cano KB, Campos I, Tao X, Maheshwari V, Brown J, Cornejo B, Handelman G, Thijssen S, Kotanko P: Removal of protein-bound uremic toxins during hemodialysis using a binding competitor. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 394–402, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.05240418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Wang Y, Xu X, Cao W, Shen Z, Wang N, Leng J, Zou N, Shang E, Zhu Z, Guo J, Duan J: Improved dialysis removal of protein-bound uremic toxins by salvianolic acids. Phytomedicine 57: 166–173, 2019. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kochansky CJ, McMasters DR, Lu P, Koeplinger KA, Kerr HH, Shou M, Korzekwa KR: Impact of pH on plasma protein binding in equilibrium dialysis. Mol Pharm 5: 438–448, 2008. 10.1021/mp800004s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Etinger A, Kumar SR, Ackley W, Soiefer L, Chun J, Singh P, Grossman E, Matalon A, Holzman RS, Meijers B, Lowenstein J: The effect of isohydric hemodialysis on the binding and removal of uremic retention solutes [published correction appears in PLoS One 13: e0200980, 2018 10.1371/journal/pone.0200980]. PLoS One 13: e0192770, 2018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krieter DH, Devine E, Körner T, Rüth M, Wanner C, Raine M, Jankowski J, Lemke HD: Haemodiafiltration at increased plasma ionic strength for improved protein-bound toxin removal. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 219: 510–520, 2017. 10.1111/apha.12730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saar-Kovrov V, Zidek W, Orth-Alampour S, Fliser D, Jankowski V, Biessen EAL, Jankowski J: Reduction of protein-bound uraemic toxins in plasma of chronic renal failure patients: A systematic review [published online ahead of print April 1, 2021]. J Intern Med 10.1111/joim.13248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yen SC, Liu ZW, Juang RS, Sahoo S, Huang CH, Chen P, Hsiao YS, Fang JT: Carbon nanotube/conducting polymer hybrid nanofibers as novel organic bioelectronic interfaces for efficient removal of protein-bound uremic toxins. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11: 43843–43856, 2019. 10.1021/acsami.9b14351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yatzidis H, Yulis G, Digenis P: Hemocarboperfusion-hemodialysis treatment in terminal renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl (7): S312–S314, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gelfand MC, Winchester JF: Hemoperfusion results in uremia. Clin Nephrol 11: 107–110, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghannoum M, Hoffman RS, Gosselin S, Nolin TD, Lavergne V, Roberts DM: Use of extracorporeal treatments in the management of poisonings. Kidney Int 94: 682–688, 2018. 10.1016/j.kint.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dinh DC, Recht NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Coated carbon hemoperfusion provides limited clearance of protein-bound solutes. Artif Organs 32: 717–724, 2008. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2008.00594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark WR, Ferrari F, La Manna G, Ronco C: Extracorporeal sorbent technologies: Basic concepts and clinical application. Contrib Nephrol 190: 43–57, 2017. 10.1159/000468911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheah WK, Ishikawa K, Othman R, Yeoh FY: Nanoporous biomaterials for uremic toxin adsorption in artificial kidney systems: A review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 105: 1232–1240, 2017. 10.1002/jbm.b.33475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandeman SR, Zheng Y, Ingavle GC, Howell CA, Mikhalovsky SV, Basnayake K, Boyd O, Davenport A, Beaton N, Davies N: A haemocompatible and scalable nanoporous adsorbent monolith synthesised using a novel lignin binder route to augment the adsorption of poorly removed uraemic toxins in haemodialysis. Biomed Mater 12: 035001, 2017. 10.1088/1748-605X/aa6546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li WH, Yin YM, Chen H, Wang XD, Yun H, Li H, Luo J, Wang JW: Curative effect of neutral macroporous resin hemoperfusion on treating hemodialysis patients with refractory uremic pruritus. Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e6160, 2017. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto S, Sato M, Sato Y, Wakamatsu T, Takahashi Y, Iguchi A, Omori K, Suzuki Y, Ei I, Kaneko Y, Goto S, Kazama JJ, Gejyo F, Narita I: Adsorption of protein-bound uremic toxins through direct hemoperfusion with hexadecyl-immobilized cellulose beads in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Artif Organs 42: 88–93, 2018. 10.1111/aor.12961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.García Martínez JJ, Bendjelid K: Artificial liver support systems: What is new over the last decade? Ann Intensive Care 8: 109, 2018. 10.1186/s13613-018-0453-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meijers BK, Weber V, Bammens B, Dehaen W, Verbeke K, Falkenhagen D, Evenepoel P: Removal of the uremic retention solute p-cresol using fractionated plasma separation and adsorption. Artif Organs 32: 214–219, 2008. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brettschneider F, Tölle M, von der Giet M, Passlick-Deetjen J, Steppan S, Peter M, Jankowski V, Krause A, Kühne S, Zidek W, Jankowski J: Removal of protein-bound, hydrophobic uremic toxins by a combined fractionated plasma separation and adsorption technique. Artif Organs 37: 409–416, 2013. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2012.01570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meijers BK, Hoylaerts MF, Evenepoel P: Coagulation and fractionated plasma separation and adsorption. Am J Transplant 9: 242–243, 2009. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer TW, Peattie JW, Miller JD, Dinh DC, Recht NS, Walther JL, Hostetter TH: Increasing the clearance of protein-bound solutes by addition of a sorbent to the dialysate. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 868–874, 2007. 10.1681/ASN.2006080863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo FJ, Patel KP, Marquez IO, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Effect of increasing dialyzer mass transfer area coefficient and dialysate flow on clearance of protein-bound solutes: A pilot crossover trial. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 1042–1049, 2009. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.01.265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sirich TL, Luo FJ, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Selectively increasing the clearance of protein-bound uremic solutes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1574–1579, 2012. 10.1093/ndt/gfr691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carpentier B, Ash SR: Sorbent-based artificial liver devices: Principles of operation, chemical effects and clinical results. Expert Rev Med Devices 4: 839–861, 2007. 10.1586/17434440.4.6.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haroon S, Davenport A: Haemodialysis at home: Review of current dialysis machines. Expert Rev Med Devices 15: 337–347, 2018. 10.1080/17434440.2018.1465817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gurland HJ, Fernandez JC, Samtleben W, Castro LA: Sorbent membranes used in a conventional dialyzer format. In vitro and clinical evaluation. Artif Organs 2: 372–374, 1978. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1978.tb01624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malchesky PS, Piatkiewicz W, Varnes WG, Ondercin L, Nosé Y: Sorbent membranes: Device designs, evaluations and potential applications. Artif Organs 2: 367–371, 1978. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1978.tb01623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mardini HA, Hoenich N, Bartlett K, Record CO: Comparative value of different dialysis membranes, including a carbon coated membrane for removal of noxious substances in hepatic coma. Int J Artif Organs 2: 290–295, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geremia I, Bansal R, Stamatialis D: In vitro assessment of mixed matrix hemodialysis membrane for achieving endotoxin-free dialysate combined with high removal of uremic toxins from human plasma. Acta Biomater 90: 100–111, 2019. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.ter Beek OEM, van Gelder MK, Lokhorst C, Hazenbrink DHM, Lentferink BH, Gerritsen KGF, Stamatialis D: In vitro study of dual layer mixed matrix hollow fiber membranes for outside-in filtration of human blood plasma. Acta Biomater 123: 244–253, 2021. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.12.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kato S, Otake KI, Chen H, Akpinar I, Buru CT, Islamoglu T, Snurr RQ, Farha OK: Zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks for the removal of protein-bound uremic toxin from human serum albumin. J Am Chem Soc 141: 2568–2576, 2019. 10.1021/jacs.8b12525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen Y, Shen Y, Bi X, Li J, Chen Y, Zhu Q, Wang Y, Ding F: Linoleic acid-modified liposomes for the removal of protein-bound toxins: An in vitro study [published online ahead of print November 2, 2020]. Int J Artif Organs 10.1177/0391398820968837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Han L, Xie J, Liu S, Jia L: Multi-sites polycyclodextrin adsorbents for removal of protein-bound uremic toxins combining with hemodialysis. Carbohydr Polym 247: 116665, 2020. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shinaberger JH, Shear L, Clayton LE, Barry KG, Knowlton M, Goldbaum LR: Dialysis for intoxication with lipid soluble drugs: Enhancement of glutethimide extraction with lipid dialysate. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 11: 173–177, 1965. 10.1097/00002480-196504000-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ward KW, Medina SJ, Portelli ST, Mahar Doan KM, Spengler MD, Ben MM, Lundberg D, Levy MA, Chen EP: Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo microdialysis recovery of SB-265123 using Intralipid and Encapsin as perfusates. Biopharm Drug Dispos 24: 17–25, 2003. 10.1002/bdd.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eloot S, Torremans A, De Smet R, Marescau B, De Deyn PP, Verdonck P, Vanholder R: Complex compartmental behavior of small water-soluble uremic retention solutes: Evaluation by direct measurements in plasma and erythrocytes. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 279–288, 2007. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ponda MP, Quan Z, Melamed ML, Raff A, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Methylamine clearance by haemodialysis is low. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1608–1613, 2010. 10.1093/ndt/gfp629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kikuchi K, Itoh Y, Tateoka R, Ezawa A, Murakami K, Niwa T: Metabolomic analysis of uremic toxins by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 878: 1662–1668, 2010. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rhee EP, Souza A, Farrell L, Pollak MR, Lewis GD, Steele DJ, Thadhani R, Clish CB, Greka A, Gerszten RE: Metabolite profiling identifies markers of uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1041–1051, 2010. 10.1681/ASN.2009111132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mair RD, Sirich TL, Plummer NS, Meyer TW: Characteristics of colon-derived uremic solutes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1398–1404, 2018. 10.2215/CJN.03150318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kalim S, Rhee EP: An overview of renal metabolomics. Kidney Int 91: 61–69, 2017. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basile C, Casino FG, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Is incremental hemodialysis ready to return on the scene? From empiricism to kinetic modelling. J Nephrol 30: 521–529, 2017. 10.1007/s40620-017-0391-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Casino FG, Basile C, Kirmizis D, Kanbay M, van der Sande F, Schneditz D, Mitra S, Davenport A, Gesuldo L; Eudial Working Group of ERA-EDTA: The reasons for a clinical trial on incremental haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 2015–2019, 2020. 10.1093/ndt/gfaa220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leong SC, Sao JN, Taussig A, Plummer NS, Meyer TW, Sirich TL: Residual function effectively controls plasma concentrations of secreted solutes in patients on twice weekly hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1992–1999, 2018. 10.1681/ASN.2018010081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pham NM, Recht NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Removal of the protein-bound solutes indican and p-cresol sulfate by peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 85–90, 2008. 10.2215/CJN.02570607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meyer TW, Sirich TL, Fong KD, Plummer NS, Shafi T, Hwang S, Banerjee T, Zhu Y, Powe NR, Hai X, Hostetter TH: Kt/Vurea and nonurea small solute levels in the Hemodialysis Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3469–3478, 2016. 10.1681/ASN.2015091035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sirich TL, Fong K, Larive B, Beck GJ, Chertow GM, Levin NW, Kliger AS, Plummer NS, Meyer TW; Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Trial Group: Limited reduction in uremic solute concentrations with increased dialysis frequency and time in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Daily Trial. Kidney Int 91: 1186–1192, 2017. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sirich TL, Meyer TW: Intensive hemodialysis fails to reduce plasma levels of uremic solutes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 361–362, 2018. 10.2215/CJN.00950118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Basile C, Davenport A, Mitra S, Pal A, Stamatialis D, Chrysochou C, Kirmizis D: Frontiers in hemodialysis: Innovations and technological advances. Artif Organs 45: 175–182, 2021. 10.1111/aor.13798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gura V, Rivara MB, Bieber S, Munshi R, Smith NC, Linke L, Kundzins J, Beizai M, Ezon C, Kessler L, Himmelfarb J: A wearable artificial kidney for patients with end-stage renal disease. JCI Insight 1: 86397, 2016. 10.1172/jci.insight.86397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sirich TL, Funk BA, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Prominent accumulation in hemodialysis patients of solutes normally cleared by tubular secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 615–622, 2014. 10.1681/ASN.2013060597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]