Abstract

This bibliometric analysis seeks to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted submission rates to Annals of Family Medicine by gender. Women represented 46.3% of all manuscript submissions included in our study (n = 1,964/4,238), spanning from January 1, 2015 to July 15, 2020. The overall volume of submissions increased during COVID-19 in comparison to pre-pandemic months; however, this increase was not evenly distributed among men and women (122% increase vs 101% increase, respectively). In the early months of the pandemic, 244 submissions were authored by men (58.5%), and 173 submissions were authored by women (41.5%). The gap in women’s submission rates is troubling, as it suggests they may be at greater risk of falling behind male colleagues during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key words: gender, authorship, bibliometrics, women, disparities, scholarly productivity

INTRODUCTION

Gender disparities in academic medicine have been well documented many years before the existence of COVID-19.1-4 Since the beginning of the shelter-in-place orders during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, however, women scientists realized a significant downturn in work productivity in comparison to their male counterparts.5 This finding is particularly stark for women with children under the age of 5 years.6 Even in family medicine, a specialty that recognizes more gender parity than others and has a reputation for being “family friendly,” disparities exist among academic leadership positions.1,7 Research publications are a critical piece of academic promotion in any field, this study therefore seeks to explore how COVID-19 impacted submission rates with respect to gender in a prominent primary care journal.

METHODS

We conducted a bibliometric analysis of submissions to the Annals of Family Medicine to explore the impact of COVID-19 on scholarly productivity. This journal was selected for its ranking as the top primary care journal based on publication volume and number of citations.8 Submission data included first author name, manuscript type, manuscript title, and date received. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board reviewed this study (STU00213662).

Submission volume was the primary outcome of interest. We calculated the percentages of submissions by gender during the COVID-19 pandemic (operationally defined as April 1, 2020 and beyond). For added context, we analyzed submission data over the past 5 years to serve as a benchmark comparison. Additionally, we examined the distribution of author gender by submission type (eg, original research, special reports) as some article types may be viewed more favorably in promotion and tenure considerations.

Author gender was derived algorithmically based on first name using the Gender API, a database derived from publicly available government records and social networks. This approach is widely used and previously validated.9-11 An exact binomial test was used to compare the observed proportion of women authors to our hypothesized population value of 0.50. R statistical software version 3.6.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) and SPSS statistical software version 26 for Windows (IBM Corp) were used to conduct statistical analyses and generate figures.

RESULTS

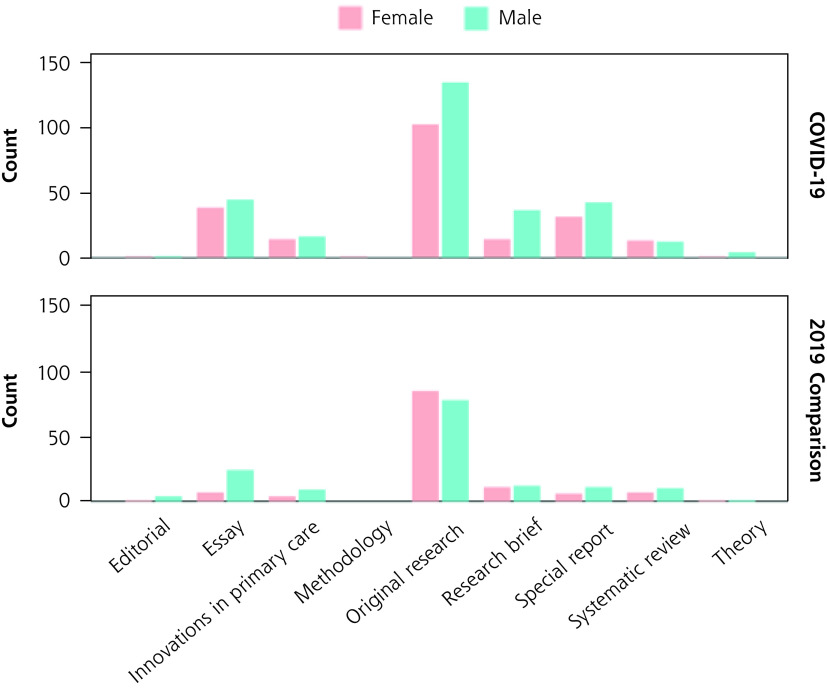

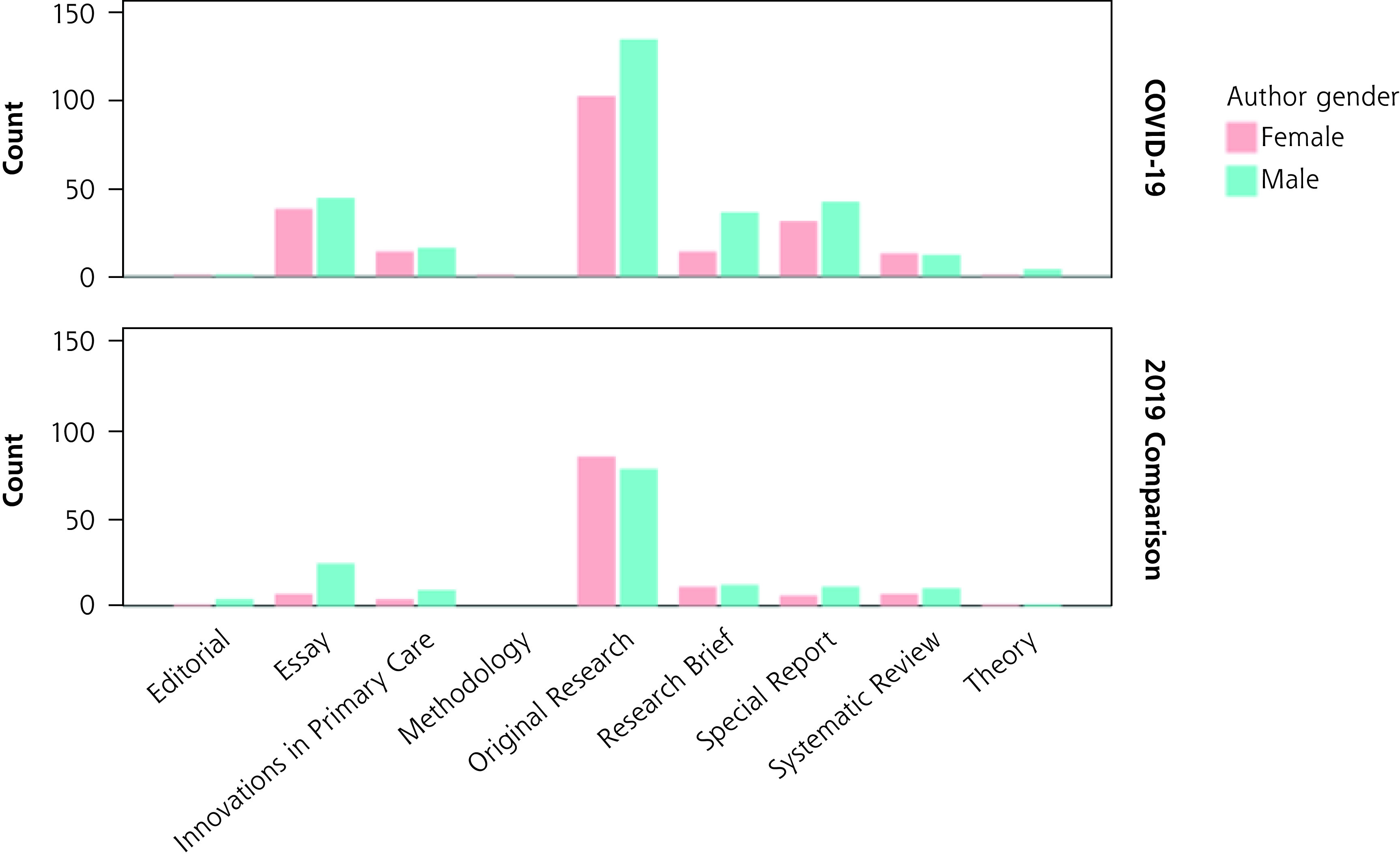

A total of 4,325 submissions were received between January 1, 2015 and July 15, 2020. First-author gender was derived algorithmically for 4,238 submissions (98%). Women represented 46.3% of all submissions (editorials, essays, innovations in primary care, methodology, original research, research briefs, special reports, systematic reviews, and theory articles (Figure 1)).

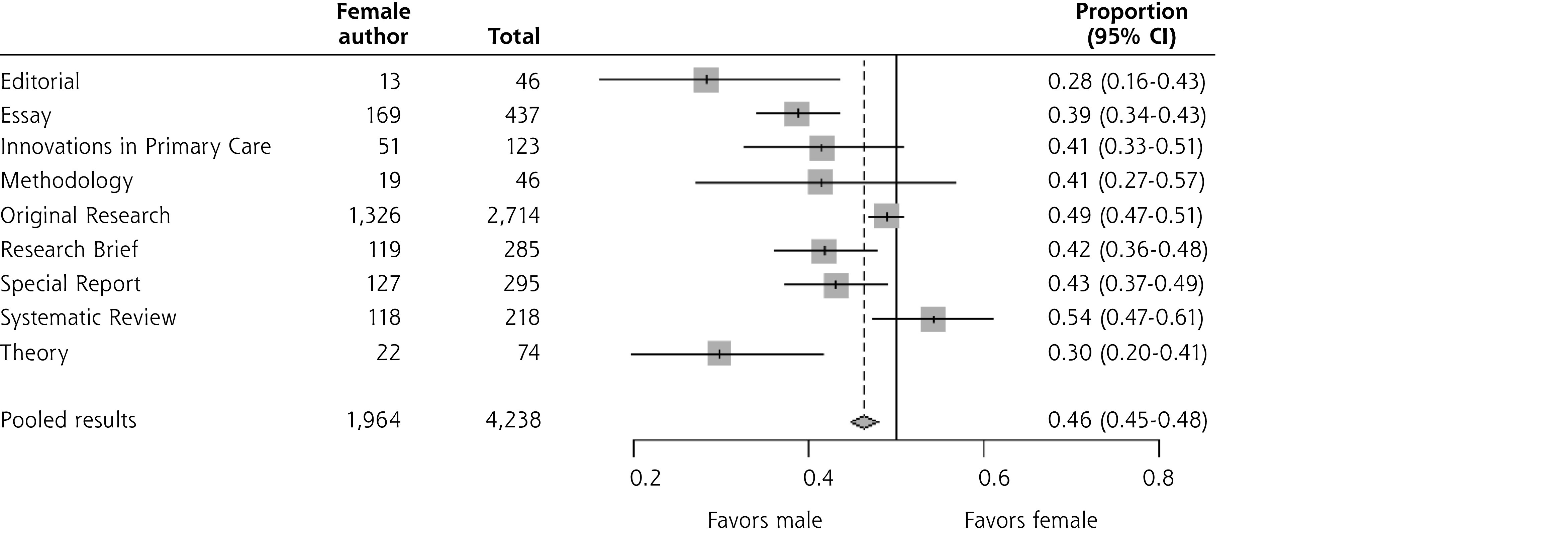

Figure 1.

Article submission type and author gender, 2015-2020.

The overall volume of submissions to Annals of Family Medicine increased during COVID-19 compared with prepandemic months, as shown in the overlapping histograms presented in Figure 2. Submissions peaked in April 2020 amid widespread stay-at-home orders; however, this increase was not evenly distributed. In the early months of the pandemic, 244 submissions were authored by men (58.5%), and 173 submissions were authored by women (41.5%). The observed proportion of submissions authored by women during the pandemic differed significantly from our hypothesized value of 0.50 (P <0.001, 95% CI, 0.367-0.464). Annals of Family Medicine flagged 192 submissions related to the COVID-19 pandemic; of these 76 (40%) were authored by women.

Figure 2.

Annals of Family Medicine journal submissions by gender, 2015-2020.

Men submitted more articles during the pandemic (n = 244) compared with the same period in 2019 (n = 110 articles), representing a 122% increase. Women also submitted more articles during the pandemic (n = 173) compared with the same period in 2019 (n = 86); however, the percentage increase was lower, at 101%. Because different manuscript types may carry more weight in promotion considerations, Figure 3 illustrates the breakdown in submissions by article type and gender. Men submitted more original research articles and research briefs (n = 107 and n = 32, respectively) compared with women colleagues (n = 78 and n = 10). Pre-pandemic submission differences were much less pronounced.

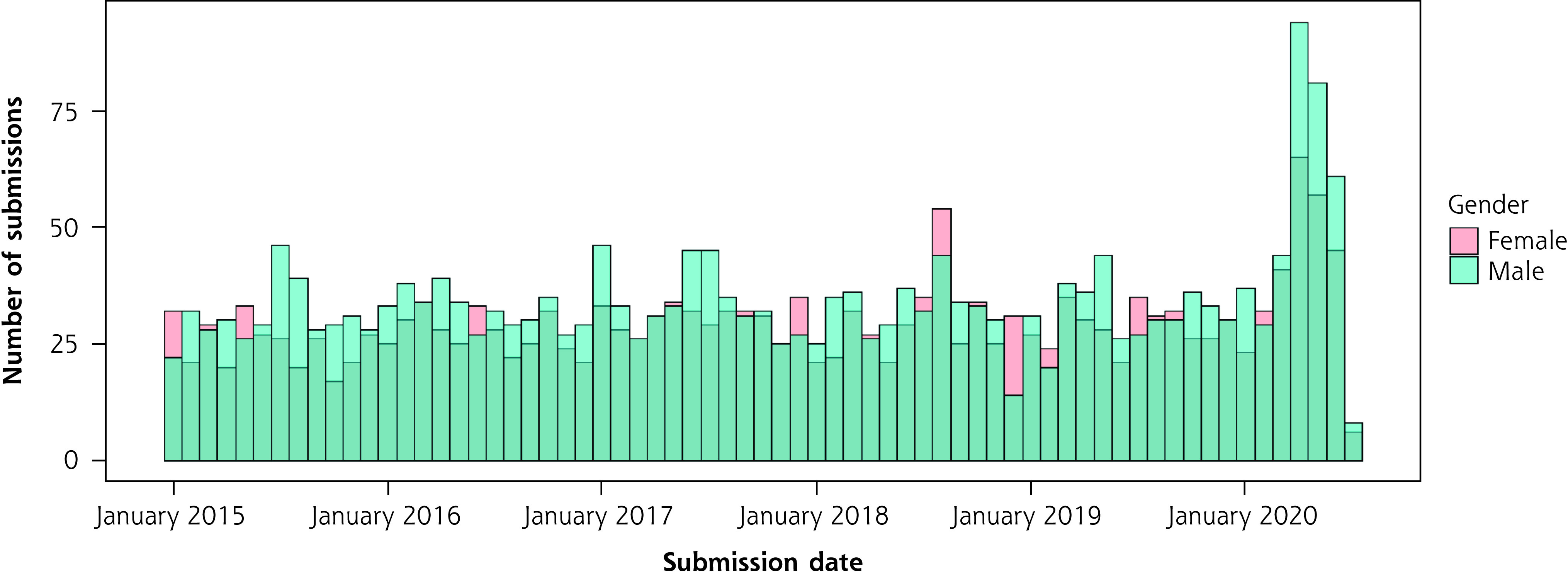

Figure 3.

Submissions by manuscript type, 2019-2020.

DISCUSSION

The gap in women’s submission rates is troubling, as it suggests they may be at greater risk of falling behind male colleagues during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Early-career researchers may lose momentum and opportunities to publish timely and seminal works, making them less competitive in an academic job market down the road. As women represent a disproportionate share of adjunct faculty without paid leave and other benefits, they may be more vulnerable to budget cuts and forced to leave the labor market altogether.12 These detrimental downstream effects may outlast the COVID-19 pandemic itself.

We feel that the best way to tackle this issue is to address it on multiple fronts. Greater recognition of gender disparities may be an initial step toward affecting change. Academic medical centers can reevaluate promotion and tenure considerations to reflect the shift in educational and clinical needs in response to COVID-19. Additionally, parental leave policies, childcare policies, and tenure extensions can help mitigate challenges posed by the pandemic.

This study has several limitations. Data are limited to a single journal, and gender categorization was limited to binary “male” and “female” and do not reflect nonbinary genders. Our analysis is limited to first authors and does not include senior authors, or other authorship positions. We examined submission data as a metric of productivity; future research on publication data would provide additional insight on gender disparities. Last, our findings may mask important heterogeneity, as the COVID-19 pandemic may disproportionately affect specific subgroups (eg, caregivers, single parents, those without access to childcare, etc) not captured in our data set.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated rapid changes to the academic workforce, with differential impacts by gender. Analyzing Annals of Family Medicine submission data, we found an overall increase in submissions compared with years prior; men, however, submitted manuscripts at higher rates than women. Though these differences likely reflect pre-existing disparities in academia and beyond, without intervention, COVID-19 may exacerbate gender disparities for years to come.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Read or post commentaries in response to this article.

References

- 1.Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg JJ, Skae C, Sampson B. Gender gap, disparity, and inequality in peer review. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2602-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raj A, Carr PL, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Longitudinal analysis of gender differences in academic productivity among medical faculty across 24 medical schools in the United States. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1074-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KM, Edberg D, Wheat S, Clements DS. Prevalence of women authors in family medicine literature. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1916029-e1916029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature. 2020;581(7809):365-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(3):341-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen ST, Jalal S, Ahmadi M, et al. Influences for gender disparity in academic family medicine in North American medical schools. Cureus. 2020; 12(5):e8368-e8368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.InCites Journal Citation Reports . 2019 Journal Impact Factor. Clarivate Analytics; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santamaría L, Mihaljević H. Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2018;4:e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wais K. Gender prediction methods based on first names with genderizeR. The R Journal. 2016;8:17-37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Predict gender from names using historical data. R package version 0.5.4.1000. Accessed Jul 31, 2020. https://github.com/ropensci/gender

- 12.Smalley A. Higher education responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). National Conference of State Legislatures. Accessed May 15, 2020. Updated Mar 22, 2021. https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/higher-education-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx2020