Abstract

Data in this study supported a model of internalization that included both transmission and transactional variables. Two sets of hierarchical linear regression models were conducted on data collected from the fathers, mothers, and adolescents (10 to 12 years old) in 171 intact Caucasian families. One set predicted adolescent religious behavior, the other predicted the importance of religion to child. Transmission variables (parental religious behavior and parental desire for child to be religious) predicted the most variance in all models. Dyadic discussions of faith (transactional) predicted significant variance in all models. Child gender had a direct effect only on adolescent religious behavior. A significant 3-way interaction occurred between child gender, parental desire for child to be religious, and dyadic discussions when predicting importance of religion to child, with child and parent gender dyads interacting in a complex manner.

A wise son maketh a glad father; but a foolish son is the heaviness of his mother.

Proverbs 10:1 (American Standard Version)

The question of whether and how parents can “pass on” their most deeply held values to their children has been of vital interest to parents themselves and to society in general from early Biblical times through today. By virtue of their roles, parents are the primary socializing agents for their children. Internalization, the socialization process by which children come to learn, value, and acquire the beliefs and behaviors of their parents, has been empirically studied for many years from various developmental and nondevelopmental perspectives (Baldwin, 1911; Bandura & Walters, 1959, 1963; De-Charms, 1968; Freud, 1957; Janet, 1930;Piaget, 1970; Schafer, 1968; Vygotsky, 1987).

For most of this time, two main groups of theories have dominated the discussion (Lawrence & Valsiner, 1993). In the more traditional cultural transmission model, values are passed from the parent to the child unidirectionally. The child is seen as a passive recipient, accepting or not accepting the values transmitted by parents who are perceived as the active agents in the internalization process. The alternative transactional, sometimes called transformational (Lawrence & Valsiner, 1993), models of internalization are drawn from more constructivist theories of development in which the child transforms or reorganizes parental input (e.g., Vygotsky, 1987). In these models, both parents and children are perceived as active agents in the internalization process (Ryan & Powelson, 1991). These transactional models convey a process involving action and intention, rather than a process characterized by passivity (Grolnick, Ryan, & Deci, 1997).

Most work in this field has not included the assessment of domain specific transactional processes. Children’s internalization of parental values has been measured by ascertaining the degree of imitation or compliance in behavior across a variety of settings (Heider, 1958; Schafer, 1968). There were two disadvantages to this approach. Internalization of values in different domains may be differentially impacted by the use of generic, global measures of parent-child transactions. In addition, in light of societal and parental powers of coercion, external behavior may not be the most accurate measure of internalization in children (Lawrence & Valsiner, 1993).

Much of the more recent work on internalization has been sited in the domain of education. Education is clearly a domain of major and growing import in our society, and one over which children and parents frequently interact. One disadvantage of the internalization research in this domain is that most parents consider themselves to be past the age at which they can demonstrate a personal involvement in their own formal education, and they are thus reduced to a “do as I say” position. Perhaps even more significantly, children have very few actual opportunities for choice in education until middle adolescence. Children under 16 cannot choose overtly to avoid schooling without incurring severe, societally imposed sanctions (e.g., penalties for truancy). Their range of choices regarding type of educational experiences is also limited, because the majority of the curriculum is prescribed in most schools until at least the junior or senior year in high school.

The domain of religion does not suffer from these disadvantages and, for a number of reasons, offers an excellent territory within which to explore the psychological and intrafamilial correlates of internalization. Religious values are often highly salient to those who hold them; they are typically identified as among the most important values held by individuals (Gallup, 1996). Parents and children also have regular opportunities to engage together in religious behaviors, such as attending church and praying. This allows parents to model their own religious values and children to express their internalization of these values behaviorally.

There are few significant constraints in our society on either religious beliefs or behavior; our U.S. constitution, in fact, guarantees that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Adolescents do, however, experience constraints that their parents place upon them (Collins, Gleason, Sesma, Jr., 1997; Conger, 1978; Hill & Holmbeck, 1986; Staub, 1979). Parents often feel the need to exert their authority by placing boundaries on the extent to which their adolescent children can examine, discuss, and practice, or fail to practice, religious faith and behaviors (Balswick & Balswick, 1989; Staub, 1979). For some families, these constraints tend to be less absolute than those in other highly salient areas (e.g., education, drug use). At about the same time that children begin the transition into adolescence, many attend confirmation classes or receive other kinds of religious instruction (Gallup, 1996). During this phase children are often encouraged by parents or other adults to examine and define for themselves what they believe, what aspects of their beliefs are important, and how their behavior may be impacted by that belief system (Balswick & Balswick, 1989; Staub, 1979).

Four studies using self-reported data from mothers, fathers, and children (Acock & Bengston, 1978; Dudley & Dudley, 1986; Hayes & Pittlekow, 1993; Hoge, Petrillo, & Smith, 1982) have examined the influence of parental religiousness on child religiousness. All four studies reported that both mothers’ and fathers’ religious beliefs were the best predictors of adolescent religious beliefs. Both Hayes and Pittlekow (1993) and Hoge et al. (1982) found these results held true even when controlling for sociodemographic variables. Acock and Bengston (1978), as well as Hayes and Pittlekow (1993), also reported that mothers’ religious beliefs were more influential in predicting adolescent religious beliefs than fathers’ religious beliefs. Conversely, in the only study that assessed both beliefs and behaviors, Acock and Bengston (1978) reported that fathers’ religious behaviors were more influential in predicting adolescent religious behaviors.

These correlational findings support a purely transmissional model of internalization of religious values. Other researchers, however, support models of internalization that incorporate more transformational aspects by emphasizing both individual and environmental contributions (Bandura, 1991; Kihlstrom & Harackiewicz, 1990). Several early studies (Gecas, 1971; Thomas & Weigert, 1971, 1984; Weigert & Thomas, 1972) on family socialization processes related to the internalization of religiousness have found consistent associations between internalization and parental support, parental control, and degree of positive affect experienced between parent and child. Adolescents who reported high levels of both parental support and control were more likely to adhere to the forms of religiousness that their parents exhibited. Those experiencing low levels of both were less likely to hold or exhibit the religiousness of their parents.

More recent research in both the domains of educational and religious values has resulted in the development of more complex transformational models in which both parents and children are perceived as active agents in the process of internalization (Deci & Ryan, 1980; Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, & Ryan, 1991; Grolnick & Ryan, 1989; Grolnick, Ryan, & Deci, 1997; Peterson, Rollins, & Thomas, 1985; Strahan & Craig, 1995). Self-determination theory, one of the better-known transformational models, postulates that internalization takes place first within the context of the nuclear or extended family and then within the larger community. Those who argue for an understanding of internalization based on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Rigby, Deci, Patrick, & Ryan, 1992; Ryan & Lynch, 1989) describe this process as organismic, constructive, and transactional in nature. Internalization, therefore, takes place in an environmental context from which the process cannot be extricated. For example, researchers have examined how family processes such as marital or parent-child communication and relationship quality promote or inhibit the internalization of particular religious attitudes and behaviors (Ellison & Sherkat, 1993a, 1993b; Erickson, 1992; Gorsuch, 1994; Hunsberger & Brown, 1984; Ryan & Powelson, 1991).

Much of the research in this field has suffered from significant limitations in research design. Data are typically collected from only one perspective, the parent’s or (more often) the child’s. Most researchers have addressed either religious beliefs or behaviors, and yet both variables may offer important insight into religious values. Although internalization of parental values develops throughout the period of adolescence, few studies have investigated the origins of this process in early adolescence. Most researchers have collected data from late adolescents or college-aged individuals, in some cases using retrospective recollections to infer earlier processes. Only a small number of studies have used multiple perspective research designs, with data collected from mothers, fathers, and early adolescents (Dudley & Dudley, 1986; Grolnick & Ryan, 1989; Hoge et al., 1982; Peterson et al., 1985; Strahan, 1994).

Finally, few studies have assessed both parents’ and adolescents’ domain specific values and behaviors while simultaneously examining the impact of the transactional process. The main purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate whether a transactional model of religious internalization, based on self-determination theory (Grolnick & Ryan, 1989), could predict additional unique variance, over and above a more parsimonious transmission model, based on early social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1959). A second question, raised by Gorsuch (1994), is whether certain transactional processes have not only the potential to facilitate internalization, but also to inhibit or impede internalization.

A further purpose of this study was to investigate domain specificity with respect to family processes. Many of the conflicting findings related to the impact of various family processes on internalization may be due to the use of global measures of family process (see, for example, Bao, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 1999). The transactional measure in our study, dyadic discussions of faith, is a domain specific construct.

A final question in this study involves the interaction of child gender with the transmissive and transactional elements of the internalization process in the domain of religion. Several longitudinal and cross-sectional studies (Donahue & Benson, 1995; Nelson & Potvin, 1981; Sloane & Potvin, 1983; Potvin & Sloane, 1985; Reed, 1972; Weiting, 1975; Willitis & Crider, 1989; Zaenglein, Vener, & Stewart, 1975) have reported that girls are more religious than boys. The models used in this article also suggest that children with the same gender and different relational histories may internalize parental values and beliefs differentially (Brody, Flor, Hollett-Wright, & McCoy, 1998; Brody, Flor, Hollett-Wright, McCoy, & Donovan, 1999; Flor, 1998). For example, adolescent girls who experience a relationship with a parent that involves open, frequent, communication may internalize more than adolescent girls may from a parent who is less communicative and open.

Method

Sample

The participants in this study were a subset of 171 Caucasian, intact two-parent families with an early adolescent child (84 girls, 87 boys). This subset of families was taken from a larger, simple random target-age sample (n = 232) that included both Caucasian and African American families secured for a study investigating family issues related to alcohol consumption. Eighty-one of the 171 families included an older sibling who also participated in the study.

Survey Sampling Incorporated (SSI) provided a directory based listing of families in 10 rural North-eastern Georgian counties that could possibly meet the inclusion criteria for the study. SSI could provide only a list of households where a child ranging in age from 10 to 15 might be present. Pilot studies with SSI indicated that the procedures for the initial selection process from directory based listings had a better than 70% success rate for determining that a household had a child between the ages of 10 and 15. Families were then randomly selected from the list provided by SSI and sent letters notifying them that they would be receiving a telephone call from the Survey Research Center (SRC) at the University of Georgia.

Phone calls to the families were made by the staff of the SRC to determine whether the family included a child between the ages of 10 and 12, whether the two parents in the home were the biological parents of the adolescent child (step- and single-parent families were excluded), and whether they wished to receive additional information regarding the study. Families meeting this inclusion criterion were then placed on a final list from which a research assistant solicited participation in the study. Seventy-one percent of the families from this final list agreed to participate. It is important to note that while 88% of all Georgian households have telephones, those with unlisted numbers or those without telephones were automatically excluded from participation in the study.

The 61 African American families from the original sample were not included in the analyses of this study for two reasons. First, religious participation and belief in African American families may involve family processes different from those found in Caucasian families (Balk, 1983; Brody, Stoneman, & Flor, 1995; Brody, Stoneman, Flor, & McCrary, 1994; Krause & Tran, 1989; Palmer & Noble, 1986; Taylor & Chatters, 1991). Higher levels of religiousness were related to higher levels of coping and internal control in this population. Second, the small number of African American families in the sample prevented any comparative possibilities with the Caucasian families in this study.

All data used in this study were from Caucasian families with both biological parents living in the home at the time of assessment. The means and standard deviations in age for fathers, mothers, and children were 41.6 (SD = 5.6), 38.9 (SD = 4.5), and 12.0 (SD = 0.6), respectively. Median yearly family income was $45,922, with a mean of $53,978 (SD = $47,214), and range of $4,020 to $559,927.

Of the participating families, 14% had one child, 50% had two children, 29% had three, and 8% had more than three children. Seven percent of the fathers and 4% of the mothers never graduated from high school or attained a General Education Development certificate (GED), whereas 14% of the fathers and 23% of the mothers graduated from high school or attained a GED. For mothers, “some college or trade school (no degree)” was both the modal and median educational level. The mode was the same for fathers and the median was “trade school diploma/certificate or Associate of Arts degree.” Of the fathers, 17% held bachelor’s degrees, as did 13% of the mothers, whereas 15% of the fathers and 16% of the mothers held master’s, doctoral, or professional degrees.

Thirty-one of the 171 mothers (roughly 18%), without gainful employment either inside or outside the home, considered themselves to be full-time homemakers, while 36 of the mothers (roughly 21%) who had some gainful employment inside or outside the home considered themselves to be primarily full-time homemakers. Mothers with gainful employment contributed an average of 31% of their families’ incomes. Roughly 6% of the mothers and 4% of the fathers considered themselves temporarily unemployed. These data indicate the diversity of the sample with respect to level of education, family structure, and parental occupational characteristics.

Procedures

Data were collected during two visits to families’ homes, with each visit lasting approximately 3 hrs. The two visits were spaced about one week apart, as the families’ schedules permitted. Two trained researchers assisted fathers, mothers, and target children in the completion of a series of computerized questionnaires. Family members were interviewed individually in separate rooms, when space permitted, so that their responses were not affected by the presence of other members. Participants were shown how to respond to the questions using a keypad, which was shielded from the researcher’s view to ensure confidentiality of responses. Computerized questionnaires were presented in an oral interview format to approximately 10% of the participants due to either their discomfort in using the laptop computer or possible literacy concerns.

Measures

Religiousness was assessed using the Inventory of Religious Internalization (IRI; Flor, 1993), using a multivariate approach (Gorsuch, 1986; Gorsuch & McFarland, 1972; Schaefer & Gorsuch, 1991) across three domains: belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer. Items of the IRI are carefully phrased to avoid any bias toward, or against, persons of various religion affiliations (i.e., Christian, Jewish, Muslim, etc.) and those without religious affiliations. Religiousness is operationalized, for this study, according to three aspects: (a) statements relating to religious belief, (b) statements relating to religious behavior, and (c) statements relating to religious salience (i.e., importance of religion).

The version of the IRI answered by parents in this study consisted of 50 items and was divided into four sections: (a) values and beliefs, (b) motivations for religiousness, (c) religious behavior, and (d) salience and family process. In the values and beliefs section, fathers and mothers indicated whether they themselves believed in God, attended religious services, and prayed; whether they thought the target child believed in God, attended religious services, and prayed; and how strongly they wanted the target child to believe in God, attend religious services, and pray. The motivations for religiousness section used an adapted form of the Christian Religious Internalization Scale (CRIS; Grolnick & Ryan, 1987, 1989). The CRIS assessed the reasons for fathers’ and mothers’ levels of belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer, as well as the reasons to which they attributed the target child’s levels of belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer.

The religious behavior section assessed fathers’ and mothers’ frequency of attendance at religious services and denominational affiliation. The fourth section assessed other value-related issues such as the importance fathers and mothers placed on belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer, as well as the frequency and nature of discussions around issues of faith and religion between each parent and the target child.

The child version of the IRI consisted of 28 items and was divided into four sections. In the values and beliefs section, respondents indicated to what degree they themselves believed in God, attended religious services, and prayed. The motivations for religiousness section used an adapted form of the CRIS, which assessed the reasons for their levels of belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer. The religious behavior section assessed target children’s frequency of attendance at religious services and denominational affiliation. And again, the final section assessed other value related issues such as the importance that target children place on belief in God, attendance at religious services, and prayer, as well as their perceptions of the frequency and nature of discussions around issues of faith and religion between each parent and the target child.

Religious behavior.

Following Allport and Ross’s (1967), Gorsuch’s (1984), and Kirkpatrick & Hood’s (1990) suggestions for measures of religiousness that discriminate between the antireligious, the nonreligious, the indiscriminately proreligious, and the truly religious, religious behavior was operationalized through the use of a product term that included both belief and behavior. Participant responses to the question “Do you believe in God?” were dichotomized such that “No” and “I’m not sure” were assigned a value of 0, whereas “I think so” and “definitely yes” were assigned a value of 1. Participants’ responses to, “How often do you attend religious services?” were then multiplied by the dichotomized belief in God.

The product term yielded a religious behavior value of zero for persons who stated that they did not believe in God. This was done to differentiate between horizontal believers and vertical believers; Davidson (1972) characterized the former as those individuals who attend church for nonreligious reasons, because they do not believe in God. All other values remained unchanged, as their scores are multiplied by a value of one. Eleven fathers, three mothers, and two children were affected by this operationalization of religious behavior; thus only a small number of people were affected by this choice in defining religious behavior. Religious behavior, therefore, had a range of 0 to 5 for fathers, mothers and targets; a mean of 2.6, 3.0, and 3.2 for fathers, mothers, and targets respectively; and a standard deviation of 1.6,1.5, and 1.4 for fathers, mothers, and targets, respectively. Higher scores indicate higher levels of religious behavior.

Importance of religion to child.

Importance of religion to child was assessed through the sum of children’s responses to two questions: “How important is it to you that you pray?” and “How important is it to you that you attend religious services?” Responses were made using a four-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (It isn’t important at all) to 3 (very important) Due to an unforeseen programming problem in the computerized interviews, children’s responses to an intended third question, “How important is it for you to believe in God?” were not available for inclusion in this composite measure. Importance of religion to child, therefore, had a range of 0 to 6, a mean of 5.1, and a standard deviation of 1.4. Higher scores indicate higher levels for importance of religiousness.

Dyadic discussions of faith.

Fathers, mothers, and target children were asked two questions relating to parent-child discussions of faith. The first question assessed frequency of dyadic discussion (“How often do you and your [father, mother, child] talk about faith/religion?”) using a four-point Likert-type scale. Responses ranged from 0 (We never talk about it) to 3 (We talk about it a lot). The second question assessed a qualitative aspect of the discussion (“When you and your [father, mother, child] talk about your faith/religion, how does the conversation go?”). This question also used a four-point Likert-type scale. Responses to the second item ranged from 0 (We don’t talk about it) to 3 (We usually talk about it openly and everyone shares their side of the issue).

Because the frequency and qualitative aspects of the discussions about faith were highly correlated for dyads in this sample (.77 for father-child dyads and .67 for mother-child dyads) and estimates of internal consistency of the four items, two from each perspective, were acceptable (.78 for father-child dyads and .71 for mother-child dyads), responses to these two questions were summed across perspectives into a single score. This score was then used as an indicator of frequent bidirectional discussions about faith between each parent-child dyad. This decision to use a combined score was further supported by the finding that no dyads exhibited any level of bidirectionality without a moderate to high level of frequency. The data thus seemed to indicate that frequent interaction was necessary for bidirectionality of dyadic discussions about faith.

Dyadic discussions of faith thus had a range of 0–12 for both father-child and mother-child dyads, with higher scores indicating greater frequency or greater openness of parent-child discussions of religion, or both. Means were 8.19 (SD = 3.24) for father-child dyads and 9.56 (SD = 2.45) for mother-child dyads.

Parental desire for child to be religious.

The product of two sets of related questions comprised the variable of parental desire for child to be religious. The first set was the sum of parents’ responses to a series of questions “How important is it to you that your child (1) believe in God, (2) pray, and (3) attend church?” Responses to this first set of questions were made using a four-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (It isn’t important at all) to 3 (very important). The second set was the sum of answers to the series of questions, “Do you want your child to (1) believe in God, (2) pray, or (3) attend church?” Responses to this second set of questions were made using a four-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (NO) to 3 (definitely yes). Parental desire for child to be religious therefore had a range of 0 to 81 for both fathers and mothers, with means of 61.7 (SD = 24.4) for fathers and 68.5 (SD = 20.8) for mothers.

Results

Descriptive Analyses of Religious Behavior

Eighty-eight percent of fathers and 93% of mothers reported at least sometimes attending religious worship services, all of various Christian denominations. Thirty-eight percent of parents identified themselves as Baptists, and 14% identified themselves as Methodist. An additional 8% identified themselves as Presbyterians, and 6% identified themselves as members of the Christian Church. The remaining 11% (n = 19) were scattered across eight other denominations. These data indicate that the sample was religiously diverse across Christian denominations, but did not include adherents of non-Christian religions (e.g., Jewish, Muslim). The sample did include, however, a small percentage of fathers, mothers, and children who expressly stated that they did not believe in God, did not identify themselves as adherents of any religion, or did not attend any formal religious services (12%, 7%, and 7%, respectively). Although religious affiliation was not a criterion for inclusion in the study, the distribution of religious affiliations among this rural Georgian sample was not unexpected.

Seventy-seven percent of couples were religiously homogeneous with respect to church affiliation, whereas 23% were heterogeneous. Religious heterogeneity in the sample was due to one family member not attending institutional religious services (12 fathers, 4 mothers, and 5 adolescents). Eight families (5%) had both parents not attending institutional religious services. Comparisons of several measures of religious behavior for this sample with national and regional data collected from the South or Southeast by the Princeton Religion Research Center (Gallup, 1996) may be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

National and Sample Religiousness Demographics

| Variable | Nationala adult | Mother | Father | Target child |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief in God – | ||||

| Yes | 96 | 98 | 94 | 99 |

| Not sure | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| No | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Do you pray? | ||||

| Yes | 90 | 98 | 90 | 98 |

| No | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| Church attendanceb | ||||

| Weekly | 38 | 40 | 31 | 42 |

| Nearly weeklyc | 13 | 29 | 28 | 35 |

| Monthly | 17 | 14 | 19 | .12 |

| Seldom | 25 | 11 | 11 | 5 |

| Never | 6 | 7 | 12 | 5 |

| Importance of religion | ||||

| Very | 69 | 76 | 62 | 74 |

| Fairly | 22 | 18 | 21 | 20 |

| Not very | 8 | 6 | 13 | 6 |

Note. Due to rounding, percentages may add to more than 100%.

National data are from Religion in America, by G. H. Gallup, 1996, Princeton, New Jersey: The Princeton Religion Research Center. Copyright 1996 by The Princeton Religion Research Center. Reprinted with permission.

Southern regional data were used.

Response set was worded “nearly monthly” for national data; sample data response was “2 or 3 times per month.”

Regression Analyses

Separate hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted independently for mother-child and father-child dyads using each of the two direct transmission measures: (a) parental religious behavior and (b) parental desire for child to be religious as predictors of the two dependent measures: (a) child religious behavior and (b) importance of religion to child. Child gender and the single transactional measure, parent-child dyadic discussions of faith, were included in all regression analyses. Inter-correlations among all variables included in the four models are presented in Table 2. Partial Fs were used to determine whether this last variable contributed significantly in predicting outcomes beyond the effect of the direct transmission variable in each model. The partial Fs, cumulative Fs, and R2 for each model are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Independent and Dependent Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child gender | — | .15 | .07 | .05 | .00 | .07 |

| 2. Child religious behavior | .15 | — | .56***** | .64***** | .42***** | .47***** |

| 3. Parental religious behavior | −.04 | .54***** | — | .51***** | .64***** | .49***** |

| 4. Importance of religion to child | .05 | .64***** | .43***** | — | .48***** | .52***** |

| 5. Parental desire for child to be religious | .05 | .32***** | .66***** | .43***** | — | .44***** |

| 6. Dyadic discussions of faith | .08 | .42***** | .57***** | .44***** | .57***** | — |

Note. Father-child data are below diagonal, and mother-child data are above diagonal.

p < .0001.

Table 3.

Child Religious Behavior as Predicted by Parental Religious Behavior

| Variable | Cumulative F | Partial F | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 3.65a | 5.84** | .02 |

| B. Parental religious behavior | 0.70***** | 84.15***** | .33 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 33.45***** | 13.46**** | .38 |

| A × B | 27.06***** | 5.33** | .40 |

| A × C | 21.66***** | 0.42 | .40 |

| B × C | 18.38***** | 1.60 | .40 |

| A × B × C | 16.08***** | 1.79 | .41 |

| Father-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 3.65a | 5.52** | .02 |

| B. Parental religious behavior | 39.71***** | 78.21***** | .32 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 28.02***** | 3.61a | .34 |

| A × B | 23.42***** | 6.75*** | .36 |

| A × C | 18.69***** | 0.21 | .36 |

| B × C | 16.36***** | 3.34 | .38 |

| A × B × C | 13.97***** | 0.17 | .38 |

Note.

p = .06.

p < .025.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Table 4.

Child Religious Behavior as Predicted by Parental Desire for Child to be Religious

| Variable | Cumulative F | Partial F | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 3.65a | 5.34* | .02 |

| B. Parental desire for child to be religious | 20.14***** | 43.50***** | .19 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 22.75***** | 24.41***** | .29 |

| A × B | 21.10***** | 11.83**** | .34 |

| A × C | 16.79***** | 0.04 | .34 |

| B × C | 14.42***** | 2.06 | .35 |

| A × B × C | 12.77***** | 2.21 | .36 |

| Father-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 3.65a | 4.47* | .02 |

| B. Parental desire for child to be religious | 11.55***** | 21.08***** | .12 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 13.88 ***** | 16.64***** | .20 |

| A × B | 10.56***** | 0.68 | .20 |

| A × C | 8.94***** | 2.19 | .21 |

| B × C | 7.60***** | 0.94 | .22 |

| A × B × C | 6.91***** | 2.35 | .23 |

Note.

p = .06.

p < .05.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Variables were entered in the following order in all models: (a) Child Gender, (b) transmission measure [parental religious behavior or parental desire for child to be religious], (c) Dyadic Discussions of Faith, (d) Child Gender × [transmission measure], (e) Child Gender × Dyadic Discussions of Faith, (f) [transmission measure] × Dyadic Discussions of Faith, (g) Child Gender × [transmission measure] × Dyadic Discussions of Faith. Predicted values of Child Religious Behavior and Importance of Religion to Child were calculated at five standard deviations either side of the mean when significant interactions were encountered.

Child religious behavior.

Significant main effects were noted for both transmission measures (parental religious behavior and parental desire for child to be religious), as well as the transactional measure (dyadic discussions of faith) in all four regression models predicting child religious behavior (see Tables 3 & 4). As parental modeling of religious behavior increased, so did the adolescent’s religious behavior; likewise, as parents desired to see their children more religious, their children exhibited more religious behavior. As parents discussed issues of faith more with their children, child religious behavior also increased.

Total variance accounted for in predicting child religious behavior in the mother-child model that included parental religious behavior was 41% and 38% in the father-child model (see Table 3). Total variance accounted for in predicting child religious behavior in the mother-child model that included parental desire for child to be religious was 36% and 23% in the father-child model (see Table 4). Child gender predicted 2% of the variance in all four models.

Parental religious behavior predicted equally well and equally strongly in both mother-child and father-child models where it was used as the transmission measure, F(6, 163) = 84.15, p < .001, R2 = .31; and F(6, 163) = 78.21, p < .001, R2 = .30, respectively. Dyadic discussions of faith predicted an additional 5% of the variance in the mother-child model and 2% in the father-child model. Where parental desire for child to be religious was used as the transmission measure, it predicted 17% of the variance in the mother-child model, F(l, 163) = 43.50, p < .001 and 10% in the father-child model, F(6, 163) = 21.08, p < .001. Dyadic discussions of faith predicted an additional 10% of the variance in the mother-child model and 8% in the father-child model.

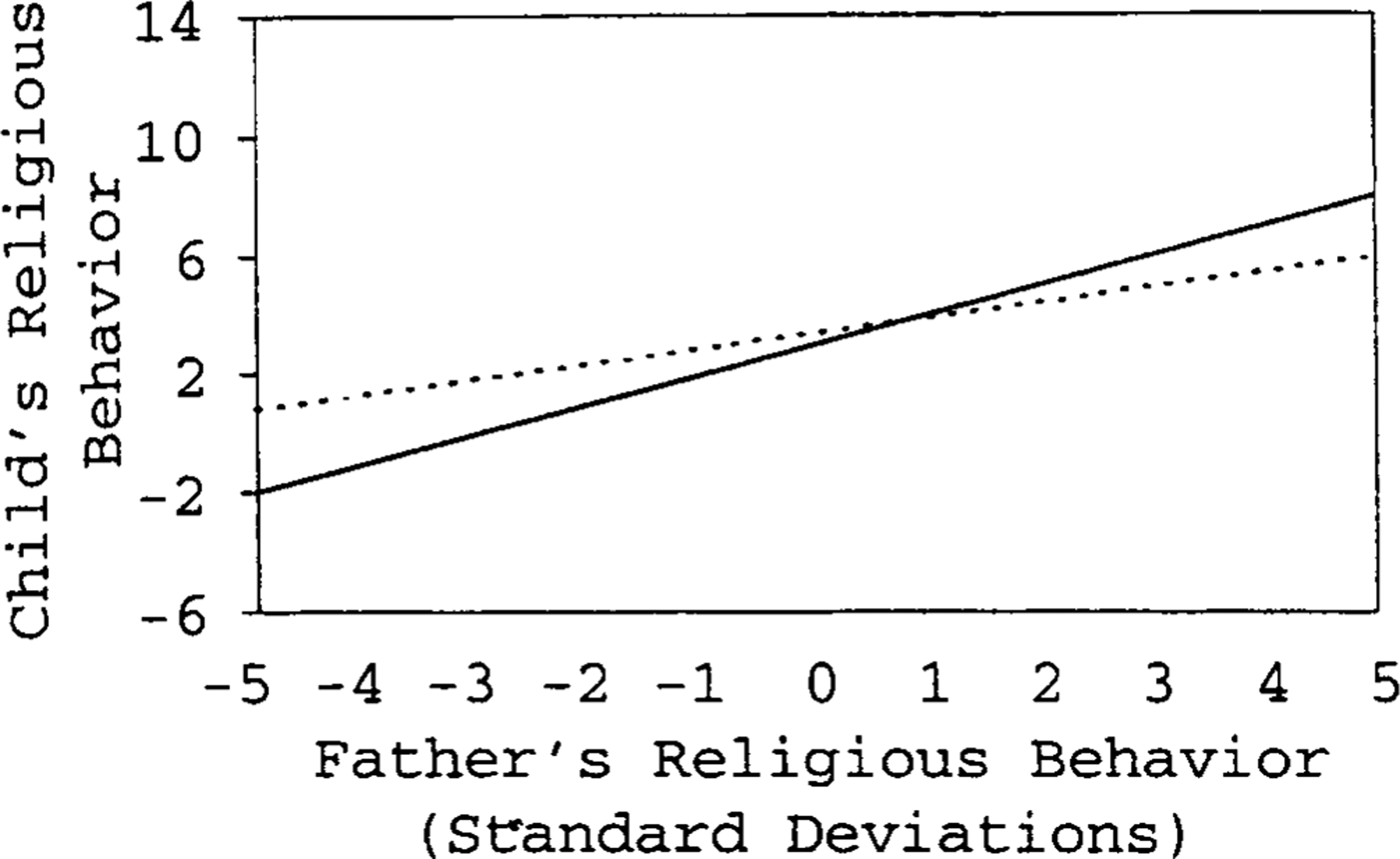

In three of the four regression models for predicting child religious behavior, the effect of the parental transmission measure was moderated significantly by child gender; parental religious behavior, F(6, 163) = 5.33, p < .025, R2 = .02 in the mother-child model and F(6, 163) = 6.75, p < .001, R2 = .02 in father-child model; parental desire for child to be religious, F(6, 163) = 11.83, p < .001, R2 = .05 in the mother-child model. No two-way interaction was noted in the father-child model involving parental desire for child to be religious. In each of the three models in which child gender interacted with the transmission measures, the slopes for boys and girls were both positive, but the slopes for boys were steeper (see Figure 1 for an example).

Figure 1.

Predicted adolescent religious behavior for interaction between child gender and parental religious behavior in father-child model. Solid line represents data for boys. Dashed line represents data for girls.

Importance of religion to child.

Significant main effects were noted for both transmission measures (parental religious behavior and parental desire for child to be religious), as well as the transactional measure (dyadic discussions of faith) in all four regression models predicting importance of religion to child (see Tables 5 and 6). As parental modeling of religious behavior increased, so did importance of religion to child; likewise as parents desired to see their children more religious, their children considered religion more important. As parents discussed issues of faith more with their children, the importance of religion also increased for the children of this study.

Table 5.

Importance of Religion to Child as Predicted by Parental Religious Behavior

| Variable | Cumulative F | Partial F | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 0.40 | 0.67 | .00 |

| B. Parental religious behavior | 29.34***** | 72.39***** | .26 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 30.59***** | 27.02***** | .35 |

| A × B | 23.40***** | 1.67 | .36 |

| A × C | 19.30***** | 2.39 | .37 |

| B × C | 19.82***** | 14.48**** | .42 |

| A × B × C | 17.03***** | 0.61 | .42 |

| Father-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 0.40 | 0.51 | .00 |

| B. Parental religious behavior | 19.84***** | 40.74***** | .19 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 17.85***** | 11.17**** | .24 |

| A × B | 13.35***** | 0.12 | .24 |

| A × C | 10.68***** | 0.24 | .24 |

| B × C | 8.84***** | 0.00 | .24 |

| A × B × C | 7.56***** | 0.13 | .25 |

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Table 6.

Importance of Religion to Child as Predicted by Parental Desire for Child to Be Religious

| Variable | Cumulative F | Partial F | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 0.40 | 0.64 | .00 |

| B. Parental desire for child to be religious | 25.82***** | 62.67***** | .24 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 30.04***** | 31.06***** | .35 |

| A × B | 25.20***** | 7.36*** | .38 |

| A × C | 20.25***** | 0.65 | .38 |

| B × C | 16.78***** | 0.04 | .38 |

| A × B × C | 15.18***** | 3.83* | .39 |

| Father-child model | |||

| A. Gender | 0.40 | 0.53 | .00 |

| B. Parental desire for child to be religious | 18.95***** | 40.30***** | .18 |

| C. Dyadic discussions of faith | 17.46***** | 12.14**** | .24 |

| A × B | 13.12***** | 0.33 | .24 |

| A × C | 10.64***** | 0.79 | .25 |

| B × C | 8.94***** | 0.61 | .25 |

| A × B × C | 8.41***** | 4.16* | .27 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Total variance accounted for in predicting importance of religion to child in the mother-child model that included parental religious behavior was 42% and 25% in the father-child model (see Table 5). Total variance accounted for in predicting importance of religion to child in the mother-child model that included parental desire for child to be religious was 39% and 27% in the father-child model (see Table 6). Main effects for child gender were not significant in any of the four models.

Where parental religious behavior was used as the transmission measure, it predicted 26% of the variance in the mother-child model, F(6, 163) = 72.39, p < .001 and 19% in the father-child model, F(6, 163) = 40.74, p < .001. In these two models, dyadic discussions of faith predicted an additional 9% and 5% of the variance, respectively. In the two models in which parental desire for child to be religious was used as the transmission measure, it predicted 24% of the variance in the mother-child model, F(6, 163) = 62.67, p < .001, and 18% in the father-child model, F(6, 163) = 40.30, p < .001. In these two models, dyadic discussions of faith predicted an additional 11% and 6% of the variance, respectively. Both transmission measures predicted more unique variance in the mother-child models than in the father-child models, whereas dyadic discussions of faith predicted a significant amount of additional variance in all four models.

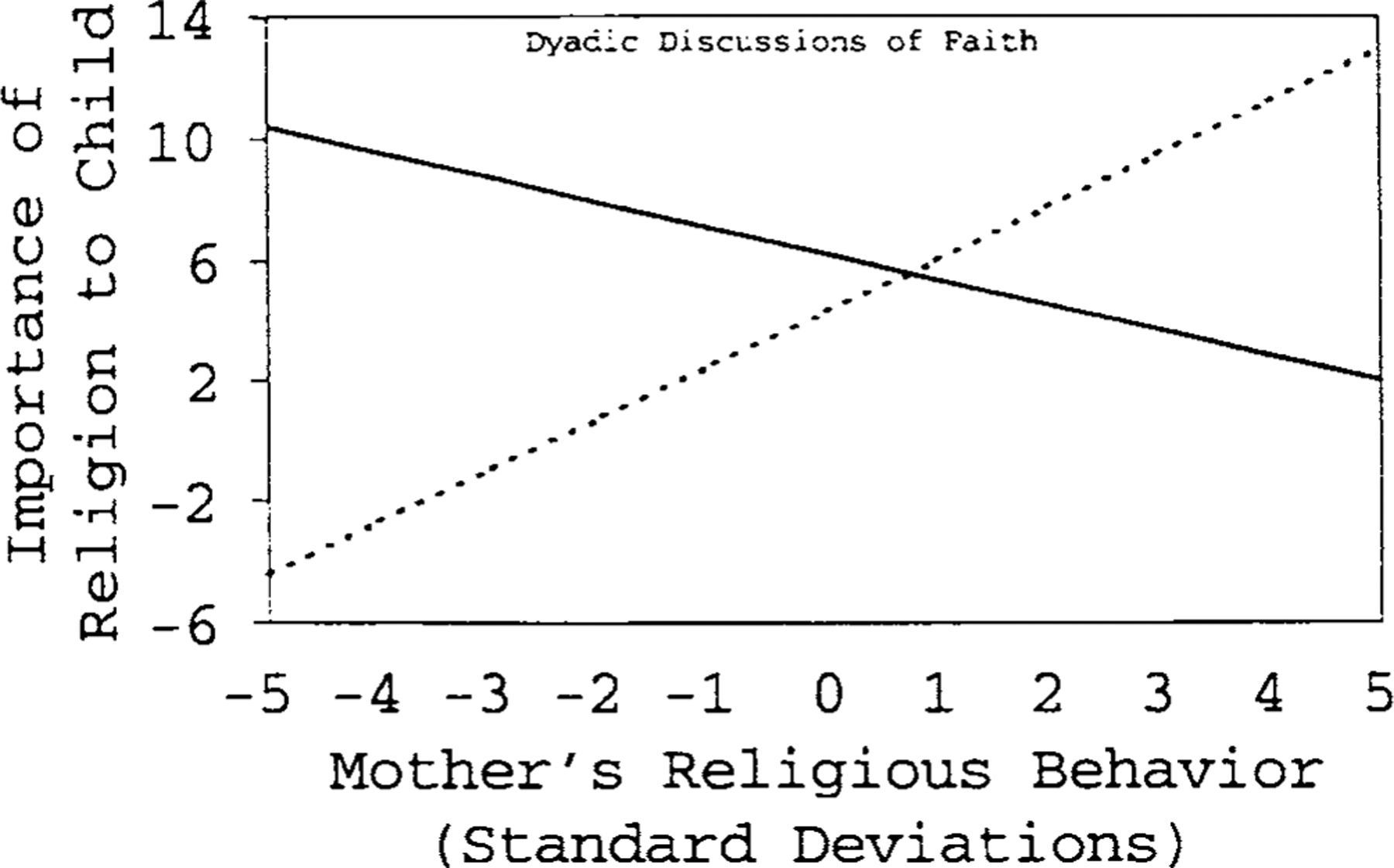

In the mother-child model that included parental religious behavior, the direct effects of the transmission and transactional measures were moderated significantly by a two-way interaction, F(l, 163) = 14.48, p < .001. No significant two-way or three-way interactions were noted in the father-child model that included parental religious behavior. In both of the importance of religion to child models that included parental desire for child to be religious, however, the direct effects of the transmission and transactional measures were moderated significantly by a three-way interaction, F(l, 163) = 3.83, p = .052 for mother-child model; F(l, 163) = 4.16, p < .05 for father-child model.

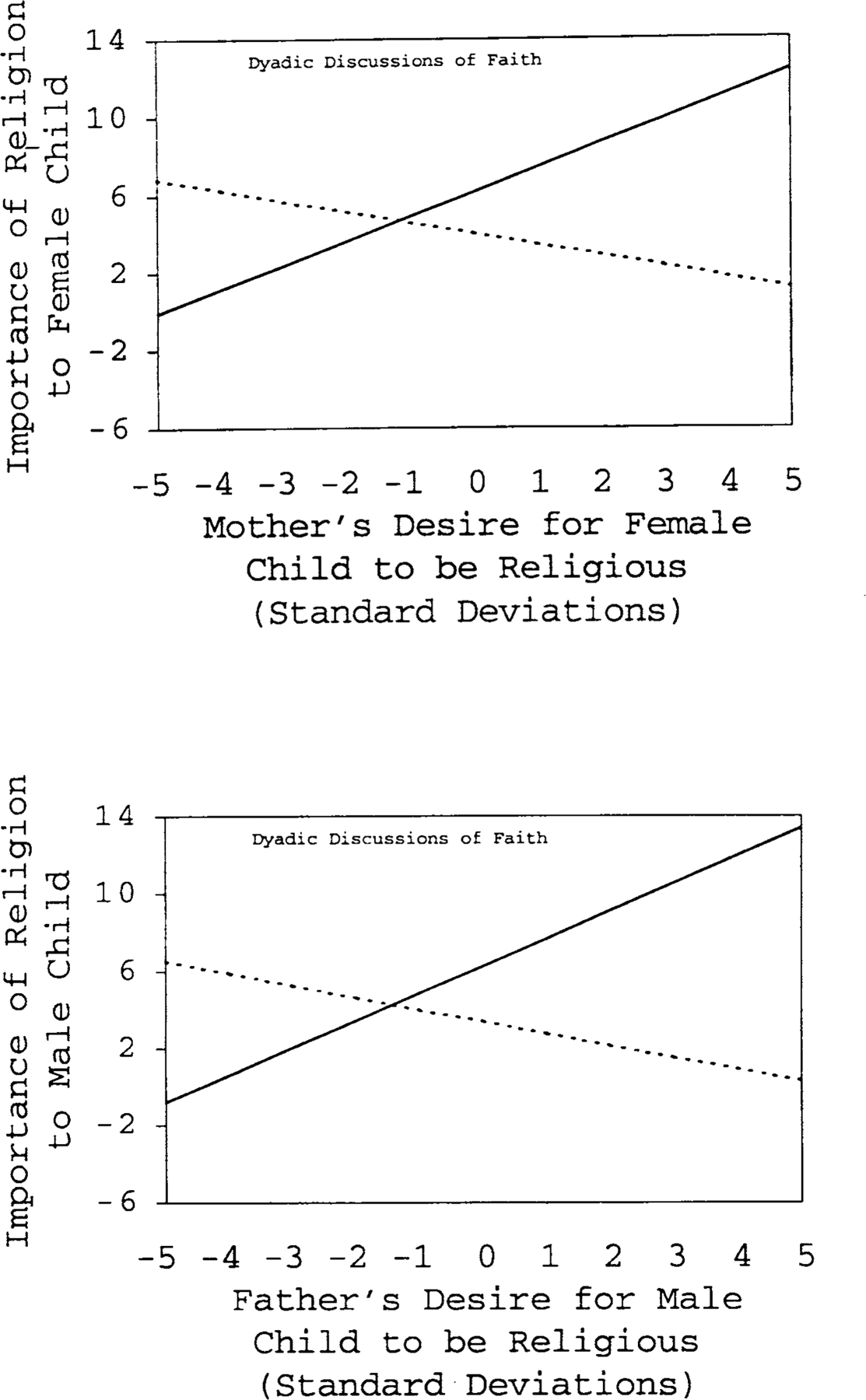

To further investigate these three-way interactions, separate regression lines for each of the four parent-child dyad combinations were plotted. Examination of these plots (see Figure 2) revealed similar slopes for the effects of dyadic discussions of faith when interacting with parental desire for child to be religious on importance of religion to child for the two same gender parent-child dyads (see Figure 3). In particular, for these same gender dyads, when parents were more desirous of having their children be religious and had more frequent and bidirectional discussions about faith, the slopes evidenced an even more positive effect on importance of religion to child. When parents were more desirous of having their children be religious, but had less frequent or unidirectional discussions about faith, the slopes evidenced an even more negative effect on importance of religion to child.

Figure 2.

Predicted importance of religion to child for interaction between parental religious behavior and dyadic discussions of faith (mother-child model). Solid line represents data for more frequent-bidirectional. Dashed line represents data for less frequent-unidirectional.

Figure 3.

Predicted importance of religion to child for interaction between parental religious behavior and dyadic discussions of faith by gender (same-gender dyads). Solid line represents data for more frequent-bidirectional. Dashed line represents data for less frequent-unidirectional.

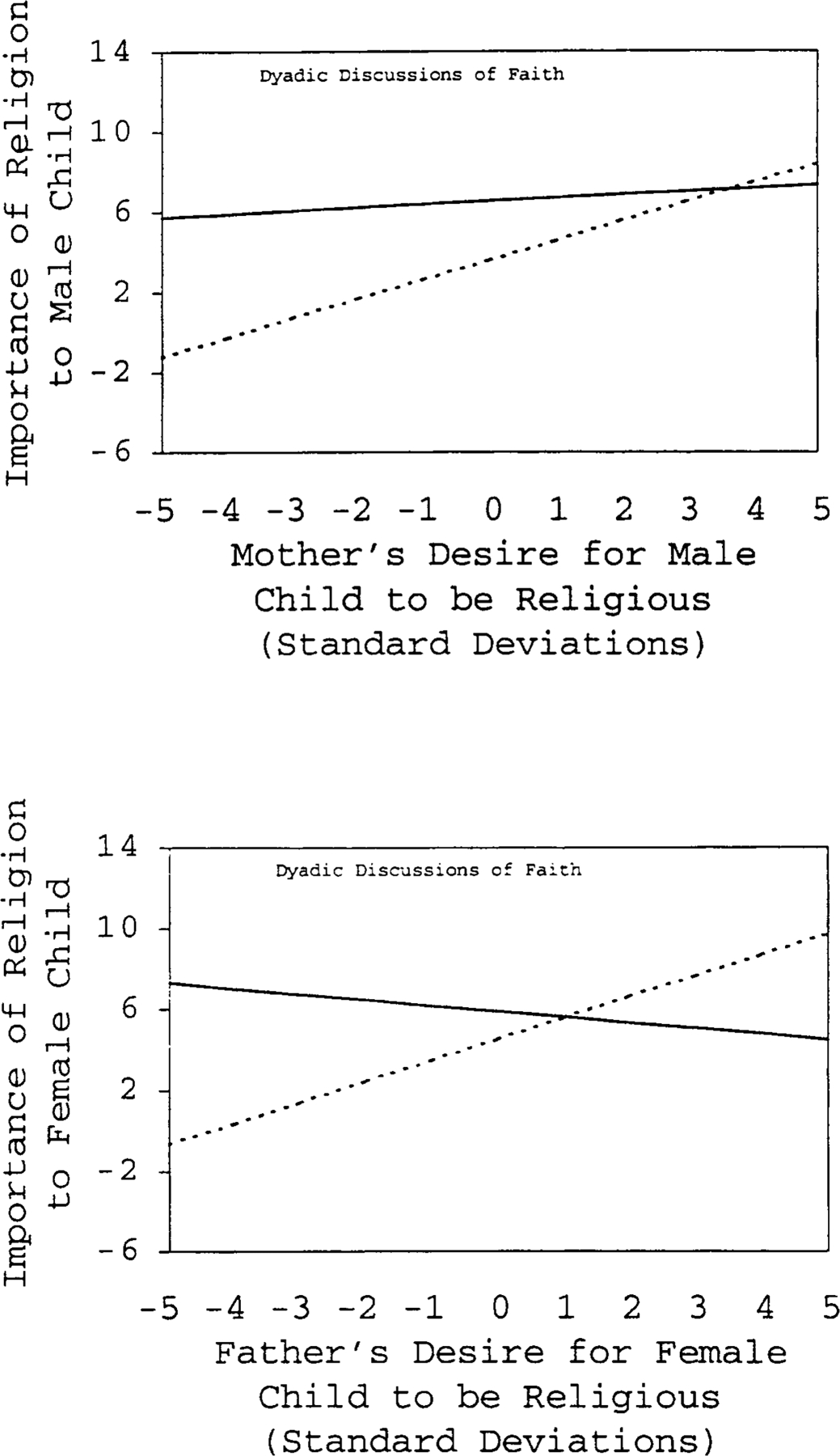

Opposite gender dyads, however, did not exhibit the same effects (see Figure 4). In particular, when parents were more desirous of having their children be religious, but had less frequent and bidirectional discussions about faith, the slopes evidenced a positive effect on importance of religion to the opposite gender child. Conversely, when parents were more desirous of having their children be religious and had more frequent or unidirectional discussions about faith, the slopes evidenced a negligible or even somewhat negative effect on importance of religion to child.

Figure 4.

Predicted importance of religion to child for interaction between parental religious behavior and dyadic discussions of faith by gender (opposite-gender dyads). Solid line represents data for more frequent-bidirectional. Dashed line represents data for less frequent-unidirectional.

A similar counterintuitive effect was noted in the plot for the two-way interaction of parental religious behavior and dyadic discussions of faith in the mother-child model predicting importance of religion to child. Even though child gender was not a significant factor in this interaction, exploratory analyses that resulted in separate plots for mother-girl and mother-boy dyads revealed that slopes for mother-boy dyads were steeper than those for mother-girl dyads, thus echoing the significant opposite gender effects in the three-way interactions mentioned earlier.

Discussion

Research based on self-determination theory often excludes the assessment of behaviors, because the beliefs leading to choice are seen as the most important aspect of adolescent internalization (Grolnick, Ryan, & Deci, 1997). Many investigators using self-determination theory have also not assessed direct links between parental values and adolescent values, preferring to examine transactional aspects between parents and children. The direct transmission variables of this study predicted the largest portions of significant unique variance across all models, confirming the importance of examining these factors.

The transactional variable of this study, dyadic discussions of faith, however, did predict significant additional and unique variance across all models. As mother- and father-child discussions of faith became more frequent and bidirectional, both adolescents’ religious behavior and the importance they attached to religion increased. The amounts of unique variance predicted by dyadic discussions of faith varied from 2% to 11% across models. This finding thus supported the main hypothesis of this study: that parent-child transactions significantly impact adolescent internalization of parental religious values and behavior. In accordance with self-determination theory (Grolnick et al., 1997), this transactional effect for dyadic discussions of faith had a greater impact in predicting importance of religion to child than actual child religious behavior, but its impact was significant for both.

Dyadic discussions of faith, as a main variable of this study, has a minor limitation that should be noted. First, no dyads were found that exhibited any level of bidirectionality without a moderate to high level of frequency. The data seemed to indicate that bidirectionality of dyadic discussions about faith required frequent interaction. Second, there were only 3 dyads that reported high frequency but low to moderate quality in interaction (“lecturing”). Thus, the upper end of the variable has considerable merit in reflecting both frequency and quality of interaction between parent and child, whereas the lower end does not infer both frequency and quality of interaction. It simply infers a low frequency of interaction between parent and child.

Child gender predicted significant, albeit small, unique variance for child religious behavior, but not for importance of religion to child. This finding is consistent with prior research in which girls have been found to be more religious in their behavior than boys (Donahue & Benson, 1995; Levitt, 1995). The significant interactions of child gender with the transmission variables (parental religious behavior and desire for child to be religious) revealed that the positive effects of the transmission variables were amplified for boys and attenuated for girls when predicting child religious behavior. Thus, the religious behavior of boys appears to be more affected by parental religious modeling than the religious behavior of girls, as indicated by the steeper slopes for boys (see Figure 1).

The three-way interactions reported in this study for predicting importance of religion to child, however, imply that the effects of open, bidirectional discussions between parents and adolescents about faith may be complexly influenced by gender identification. Self-determination theory would predict our finding that adolescents with the same genders as their parents who experienced more frequent, bidirectional transactions evidenced a more positive association with parental desire for child to be religious on the importance of religion to child. It would also predict the more negative association for importance of religion to child when children experienced less frequent or more unidirectional transactions or both, combined with lower parental desire for child to be religious. Yet neither social learning theory nor self-determination theory would predict the opposite effects noted for parents and adolescents of different genders.

This phenomenon is not readily explained because of basic gender differences in child socialization, either. Lytton and Romney’s (1991) meta-analysis of 172 studies on differentiation in child-rearing practices found little evidence for substantial or significant differences between parents’ treatment of boys and girls in the United States. The sole area of significant differentiation was in encouragement of differing, sex-typed activities, particularly by fathers. Given that girls, and indeed women across the lifespan (Cornwall, 1989), evidence more religious behavior than same-age boys and men, religiousness could have been seen in this sample as a more feminine characteristic. Fathers’ slightly lower rates of church attendance, and the higher means for mothers on parental religious behavior and parental desire for child to be religious and for mother-child dyads on dyadic discussions of faith, would seem to support this hypothesis. Yet, this hypothesis, in conjunction with Lytton and Romney’s findings, would suggest that fathers would particularly encourage girls to be religious, but, as dyadic discussions of faith between fathers and daughters increased with the fathers’ desire for child to be religious, daughters were decreasingly likely to see religion as important (see Figure 4). A similar paradoxical effect was evidenced between mother-son dyads, although slightly less strongly.

Another possibility is inherent in the operationalization of the variable dyadic discussions of faith, for which higher levels indicated greater frequency of discussions in which both parties expressed their opinions. Higher ratings between opposite gender parent-child dyads on this measure might actually reflect higher levels of conflict between parents and their opposite gender children over dissimilarities in religious behaviors and values. Such conflict could reasonably be expected to decrease children’s motivation to internalize parental values. This possibility was investigated using data from the original study measuring children’s perception of conflict, but regressions incorporating this measure did not reveal any significant role for conflict in accounting for the variance in these findings. Thus, this post hoc hypothesis was not supported.

At this time, the opposite gender findings showing paradoxical moderation of the effects of parental desire for child to be religious on importance of religion to child by dyadic discussions of faith are unexplained and appear to be a fruitful area for future research.

In summary, the direct transmission variables (parental religious behavior and parental desire for child to be religious) predicted significant unique variance for both child religious behavior and importance of religion to child, albeit parental modeling of religious behavior did better than parental desire for child to be religious and did best for predicting the religious behavior of boys. The transactional variable of dyadic discussions of faith also contributed significantly in predicting both child religious behavior and importance of religion to child, but interacted with parental desire for child to be religious in a complex manner.

Conclusions

By assessing both religious values and religious behavior, the findings of this study extend not only our knowledge of internalization, but also of the theoretical predictions of early social learning theory and self-determination theory. Clearly distinguishing the operationalization of internalizations and externalizations, as was done in this study, strengthens the finding that the strongest predictors of adolescent values and behavior are still the behaviors expressed by their parents. Thus, a simple transmission model of internalization based on a unidirectional, interpersonal process strongly predicts not only the externalizations of behavior in adolescents, but also their internalizations as well.

Transformational theories of internalization (more recent social learning theories, self-determination theory, etc.) are also supported by the findings of this study as evidenced by the direct effects of the domain specific variable dyadic discussions of faith on child religious behavior and importance of religion to child. That the transformational effect was strong and consistent across all models in predicting importance of religion to child indicates the particular utility of using a domain specific measure. Predictions were based on self-determination theory that open, bidirectional communication between parents and children about domain specific topics would better demonstrate the effect on a child’s behavior and thus enhance the child’s inner directiveness.

Child gender also had an impact on adolescent internalization of parental values and behavior in this study. These data show that child gender can moderate and even mediate the effects of parental modeling and parent-child transactions on adolescent internalization. The moderating effect was demonstrated in the differential levels of child religious behavior in boys and girls in all models. The mediational effect of child gender was apparent in the interactions between parental religious variables and child gender in five of the models tested such that boys were more responsive to both higher and lower levels of parental religiousness than were girls.

The process of adolescent internalization also differs with respect to the gender of the parent. The socialization processes of mothers and fathers may have considerable overlap, but they also have their distinctions as well (Lytton & Romney, 1991). In this study, the values and behaviors of both mothers and fathers impacted adolescent values and behaviors, but with different levels of impact and under somewhat differing conditions. It is our opinion that the question of whether the differences between mother- and father-child models reflect any qualitative differences in underlying processes is still open for discussion.

Finally, the unpredicted effects noted for opposite gender dyads in the two models predicting adolescent internalization using the internalized values of the parent suggest that the internalization process may be even more complex than either transmission-based or transformational-based theories propose. In summary, critical aspects of both transmission-based early social learning theory and self-determination theory were supported in the findings of this study. Direct transmission predicted adolescent values and behavior strongly, whereas parent-child transactions predicted unique variance over and above transmission. Domain specific assessment of parent-child transactions through dyadic discussions of faith was important in demonstrating its ability to predict both the inner directiveness of adolescents (i.e., importance) and their behaviors.

Limitations

Data in this study were collected from intact, Caucasian families in rural Georgia who were predominantly of the Christian faith. As noted in the introduction, there is reason to believe that familial communication processes and adolescent internalization of parental religious values may differ in African American families (Balk, 1983; Brody, Stoneman, & Flor, 1995; Brody, Stoneman, Flor, & McCrary, 1994; Krause & Tran, 1989; Palmer & Nobel, 1986; Taylor & Chatters, 1991). Families with non-Christian religious beliefs may also communicate these beliefs in different ways.

Although cross gender parent-child dyad effects were noted in only one of the four sets of models, caution should be taken to not generalize the findings of this study to single-parent families either, as the process of internalization in these families may vary.

For the aforementioned reasons, similar research is needed involving families from other religious backgrounds, cultural or ethnic backgrounds, single-parent or other family configurations, and those living in metropolitan or urban areas of the country. Research using both transmission and domain-specific transactional measures in other domains of interest (i.e., work, education, drugs and alcohol, money, risk taking, etc.) would expand both our knowledge and understanding of the internalization processes in general. Additional research on the specific effects of mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son, and father-daughter relationships on internalization is particularly needed (see a similar call by Cowan, Cowan, & Kerig, 1993), both to assess the robustness of the effects found in this study and to investigate alternative explanations of these findings.

Finally, although the results of this study cannot speak directly to issues of internalization outside the immediate family, it seems possible that similar mechanisms may underlie adolescents’ internalization of the values and behavior of other significant adults in their lives. Extending the scope of internalization research beyond the immediate family context seems a promising, and perhaps overdue, response to our current concerns about the many adolescents who have not, for a variety of reasons, internalized prosocial values and behaviors from their parents.

Implications for Application and Public Policy

The conclusions of this study support a long-held belief by clinicians and family educators that parental beliefs and behaviors are powerful influences on a child’s beliefs and behaviors, at least in early adolescence. Parents who want their children to both internalize and act according to their own cherished values are still best advised to model those values directly, to “walk the walk” and not just “talk the talk.”

Although both boys and girls evidenced the impact of parental modeling, the impact of modeling was strongest for boys. The data of this study also indicate that “talking the talk” matters. Frequent and open discussions were found to facilitate adolescent internalization and accentuated the effect of parental modeling. Family enrichment and counseling programs offer important settings for parents and children to learn these types of communication skills. The need for trained family educators and therapists who can mediate and teach families to talk frequently and openly about most any issue is highlighted by the findings of this study, especially for families who have not formed the habit of talking openly about such issues, as was true of about 10% of families in our sample.

Our findings seem to indicate that, at least for early adolescents, such open discussions might best be held between a child and parent of the same gender. Although direct parental modeling of desired behavior seemed to be effective in both same gender and cross gender parent-child dyads, early adolescents seemed to respond positively mainly to discussions with a parent of the same gender. This may be due to their focus on exploring and establishing a satisfactory gender identity at this age. These findings remind us that mothers and fathers are not interchangeable and that each has a role to play in children’s development.

Again, a goal of family enrichment and counseling may be to help parents understand the differing roles of mothers and fathers for children of this age. Professionals working in these areas can help parents learn to support each other in these roles, rather than competing or undermining each other because of these differences. The importance of discussion between parents and children of the same gender found in this study also supports the efforts of professionals who work with families experiencing separation or divorce to make sure that children retain meaningful and frequent contact with noncustodial parents.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by Grant AA09224 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Acock AC , & Bengston VL (1978). On the relative influence of mothers and fathers: A co-variation analysis of political and religious socialization. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 40, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW, & Ross JM (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JM (1911). Thought and things: A study of the development and meaning of thought, or genetic logic: Vol. 3. Interest and Art, 78–81. London: George Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Balk D (1983). How teenagers cope with sibling death: Some implications for school counselors. School Counselor, 31, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Balswick JO, & Balswick JK (1989). The family: A Christian perspective on the contemporary home. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, & Walters RH (1959). Adolescent aggression: A study of the influence of child-training practices and family interrelationships. New York: Ronalds Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, & Walters RH (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Bao W, Whitbeck LB, & Hoyt DR (1999). Perceived parental acceptance as a moderator of religious transmission among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL, Hollett-Wright N, & McCoy JK (1998). Children’s development of alcohol use norms: Contributions of parent and sibling norms, children’s temperament and parent-child discussions. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL, Hollett-Wright N, McCoy JK, & Donovan J (1999). parent-child relationships, child temperament profiles, and children’s alcohol use norms. Journal of Studies on Alcohol (Suppl. 13), 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, & Flor DL (1995). Parental religiosity, family processes, and youth competence in rural, two-parent African American families. Journal of Developmental Psychology, 32, 696–706. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor DL, & McCrary C (1994). Religion’s role in organizing family relationships: Family processes in rural, two-parent African-American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 878–888. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Gleason T, & Sesma A Jr., (1997). Internalization, autonomy, and relationships: Development during adolescence. In Grusec JE & Kuczynski L (Eds.), Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 78–99). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ (1978) Adolescence: A time for becoming. In Lamb ME (Ed.), Social and personality development (pp. 131–154). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall M (1989). Faith development of men and women. In Bahr SJ & Peterson ET, (Eds.), Aging and the family (pp. 115–139). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, & Kerig PK (1993). Mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters: Gender differences in family formation and parenting style. In Cowan PA & Field D (Eds.), Family, self, and society: Toward a new agenda for family research (pp. 165–195). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JD (1972). Religious belief as an independent variable. Journal for Scientific Study of Religion, 11, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- DeCharms R (1968). Personal causation. New York and London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, & Ryan RM (1980). Self-determination theory: When mind mediated behavior. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, & Ryan RM (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Vallerand RJ, Pelletier LG, & Ryan RM (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26, 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue MJ, & Benson PL (1995). Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley RL, & Dudley MG (1986). Transmission of religious values from parents to adolescents. Review of Religious Research, 28, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Sherkat DE (1993a). Conservative Protestantism and support for corporal punishment. American Sociological Review, 58, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Sherkat DE (1993b). Obedience and autonomy: Religion and parental values reconsidered. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 32, 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JA (1992). Adolescent religious development and commitment: A structural equation model of the role of family, peer group, and educational influences. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31, 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Flor DL (1993). Inventory of religious internalization. Unpublished manuscript.

- Flor DL (1998). A comparative approach to the internalization of religiousness in preadolescent youth. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S (1957). Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis: Part III. In Strachey J (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 16, pp. 243–482). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1917) [Google Scholar]

- Gallup GH (1996). Religion in America, 1996 report: Will the vitality of the church be the surprise of the 21st century? Princeton, NJ: Princeton Religion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gecas V (1971). Parental behavior and dimensions of adolescent self-evaluation. Sociometry, 34, 466–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL (1984). Measurement. The boon and bane of investigating religion. American Psychologist, 39, 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL (1986). Measuring attitudes, interests, sentiments, and values. In Cattell RB & Johnson RC (Eds.), Functional psychological testing: Principles and instruments (pp. 316–330). New York: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL (1994). Toward motivational theories of intrinsic religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(4), 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL, & McFarland SG (1972). Single vs. multiple-item scales for measuring religious values. Journal for Scientific Study or Religion, 11, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, & Ryan RM (1987). Autonomy in children’s learning: An experimental and individual difference investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, & Ryan RM (1989). Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Ryan RM, & Deci EL (1997). Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective. In Grusec JE & Kuczynski L (Eds.), Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 78–99). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BC, & Pittlekow Y (1993). Religious belief, transmission, and the family: An Australian study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 755–766. [Google Scholar]

- Heider F (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, & Holmbeck GN (1986). Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. Annals of Child Development, 3, 145–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge DR, Petrillo GH, & Smith EI (1982). Transmission of religious and social values from parents to teenage children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger B, & Brown LB (1984). Religious socialization, apostasy, and the impact of family background. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 23, 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Janet P (1930). Pierre Janet. In Murchison C (Ed.), A history of psychology in autobiography (Vol. 1, pp. 123–133). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom JF, & Harackiewicz JM (1990). An evolutionary milestone in the psychology of personality. Psychological Inquiry, 1, 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, & Hood RW Jr. (1990). Intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation: The boon or bane of contemporary psychology of religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29, 442–462. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, & Tran TV (1989). Stress and religious involvement among older blacks. Journals of Gerontology: Social Science, 44, 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JA, & Valsiner J (1993). Conceptual roots of internalization: From transmission to transformation. Human Development, 36, 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M (1995). Sexual identity and religious socialization. The British Journal of Sociology, 46, 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, & Romney DM (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 2, 267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HM, & Potvin RH (1981). Gender and regional differences in the religiosity of Protestant adolescents. Review of Religious Research, 22, 268–285. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CE, & Nobel DN (1986). Premature death: Dilemmas of infant mortality. Social Case-work, 67, 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GW, Rollins BC, & Thomas DL (1985). Parental influence and adolescent conformity. Compliance and internalization. Youth & Society, 16, 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J (1970). Piaget’s theory. In Mussen PH (Ed.), Carmichael’s manual of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 703–732). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin RH, & Sloane DM (1985). Parental control, age, and religious practice. Review of Religious Research, 27, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reed JS (1972). The enduring South. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books and D. C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby CS, Deci EL, Patrick BC, & Ryan RM (1992). Beyond the intrinsic-extrinsic dichotomy: Self-determination in motivation and learning. Motivation and Emotion, 16, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Lynch JH (1989). Emotional autonomy versus detachment: Revisiting the vicissitudes of adolescence and young adulthood. Child Development, 60, 340–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Powelson CL (1991). Autonomy and relatedness as fundamental to motivation and education. Journal of Experimental Education, 60, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer CA, & Gorsuch RL (1991). Psychological adjustment and religiousness: The multivariate belief-motivation theory of religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 448–461. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer R (1968). Aspects of internalization. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane DM, & Potvin RH (1983). Age differences in adolescent religiousness. Review of Religious Research, 25, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Staub E (1979). Positive social behavior and morality. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strahan BJ (1994). Parents, adolescents and religion. Warburton, Australia: Signs Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Strahan BJ, & Craig B (1995). Marriage, family and religion. Sydney, Australia: Signs Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (1991). Non-organizational religious participation among elderly Black adults. Journals of Gerontology: Social Science, 46, S103–S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, & Weigert AJ (1971). Socialization and adolescent conformity to significant others: A cross-national analysis. American Sociological Review, 36, 835–847. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, & Weigert AJ (1984). Adolescent identification with father and mother: A multinational study. Ada Paedologica, 1, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Vol. 1. Problems of general psychology. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert AJ, & Thomas DL (1972). Parental support, control and adolescent religiosity: An extension of previous research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 11, 389–393. [Google Scholar]

- Weiting SG (1975). An examination of intergenerational patterns of religious belief and practice. Sociological Analysis, 36, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Willitis FK, & Crider DM (1989). Church attendance and traditional religious beliefs in adolescence and young adulthood: A panel study. Review of Religious Research, 31, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zaenglein MM, Vener AM, & Stewart CS (1975). The adolescent and his religion: Beliefs in transition, 1970–1973. Review of Religious Research, 17, 51–60. [Google Scholar]