Abstract

A 62-year-old man underwent left radical nephrectomy for left renal cell carcinoma at our hospital in 1999. At the age of 79 years, he was diagnosed with intra-abdominal disseminations, lung metastases, pancreas metastases, and bilateral femoral muscle metastases during a routine follow-up computed tomography scan. The patient began treatment with pazopanib. Four years later, at the age of 83 years, he developed fever, abdominal pain, and general malaise. Blood samples showed liver dysfunction, hypoalbuminemia, and anemia. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed thickening of the small bowel wall with marked edema of the submucosa from the third part of the duodenum to the jejunum, suggesting intestinal lymphangiectasia. The diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia was confirmed by small bowel endoscopy and histological examination. The patient’s general condition improved after discontinuation of pazopanib without the need for any active therapeutic interventions. The possibility of intestinal lymphangiectasia should be considered in patients with hypoalbuminemia and general malaise during treatment with multikinase inhibitors.

Keywords: Lymphangiectasia, Multikinase inhibitors, Pazopanib, Renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Pazopanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is used in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Adverse effects such as fatigue, hand–foot syndrome, and dysgeusia have been reported; however, blood samples from patients taking pazopanib have also shown liver dysfunction, bone marrow dysfunction, and hypoalbuminemia [1].

This report describes a patient who developed fever, abdominal pain, and malaise during long-term treatment with pazopanib for metastatic RCC. He was diagnosed with lymphangiectasia, which was considered to be an adverse effect of pazopanib.

Case report

A 62-year-old man underwent left radical nephrectomy for left RCC at our hospital in 1999, and the pathological diagnosis was clear cell carcinoma, Grade 2 > 3 (i.e., mostly Grade 2 with some elements of Grade 3), pT1b. At the age of 79 years, computed tomography (CT) revealed intra-abdominal disseminations (Fig. 1), lung metastases, pancreas metastases, and bilateral femoral muscle metastases of RCC. The International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic category was “favorable risk.” Therefore, the patient was started on pazopanib therapy for recurrent RCC. The therapeutic effect of pazopanib remained a partial response for all metastatic sites during the first 3 years. However, the femoral muscle metastases began to increase in size thereafter. The adverse effects experienced by the patient until this timepoint were hand–foot syndrome, hypothyroidism, hypertension, temporary loss of appetite, and diarrhea (grade 2 complications according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography at the age of 79 showed intra-abdominal dissemination (yellow arrow). It was a single lesion, and after the start of pazopanib treatment, the size of the lesion markedly decreased and no new lesions appeared

At the age of 83 years (4 years since the start of pazopanib therapy), the patient presented with fever, abdominal pain, and malaise. Laboratory examination revealed hepatic dysfunction (aspartate aminotransferase concentration of 105 U/L), hypoalbuminemia (protein concentration of 1.5 g/dL), and progressive anemia (hemoglobin concentration of 6.7 g/dL). We decided to discontinue pazopanib therapy. Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) at that time showed very characteristic findings from the third part of the duodenum to the jejunum (Fig. 2). Based on these CECT findings, intestinal lymphangiectasia was suspected. Therefore, we decided to stop oral intake and start intravenous fluid management. We performed small bowel endoscopy and capsule endoscopy to examine the small intestine and confirmed scattered white spots, white swollen villi (Fig. 3a), and a deep ulcer (Fig. 3b) from the third part of the duodenum to the jejunum. Biopsies of the intestinal mucosa revealed lymphangiectasia in the submucosa, and the patient was diagnosed with small intestinal lymphangiectasia (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed thickening of the small bowel wall with submucosal edema (yellow arrow)

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic examination confirmed (a) scattered white spots and white swollen villi as well as (b) a deep ulcer (yellow arrow) from the third part of the duodenum to the jejunum

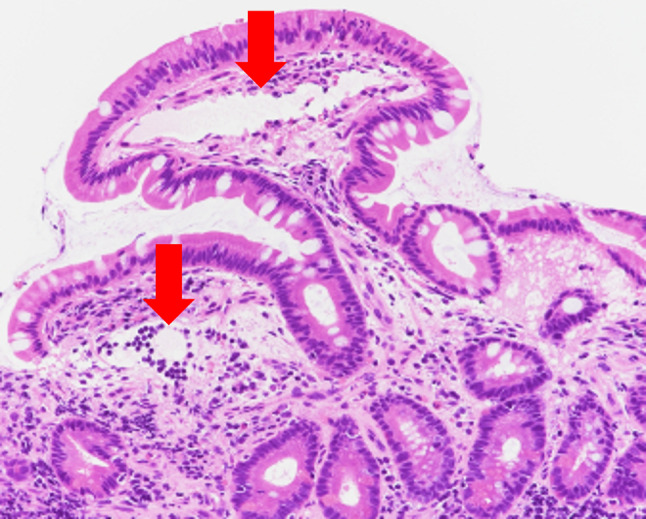

Fig. 4.

Histological examination confirmed dilated submucosal lymphatic vessels (red arrows). Hematoxylin–eosin, 20 ×

CT was performed 24 days after discontinuation of pazopanib and 10 days after initiation of fasting control, and the small intestinal abnormalities had improved from the previous examination in terms of small bowel wall thickening due to submucosal edema. The patient’s abdominal pain had also improved, and we allowed him to resume eating. Technetium-99 m diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid human serum albumin scintigraphy was performed, but no obvious evidence of protein leakage was found.

CECT at 3 months after withdrawal of pazopanib showed marked improvement in the small bowel wall findings (Fig. 5), and laboratory examination performed after 5 months showed improvement in the hepatic dysfunction (aspartate aminotransferase concentration of 24 U/L), hypoalbuminemia (protein concentration of 2.5 g/dL), and anemia (hemoglobin concentration of 8.3 g/dL) with no deterioration thereafter.

Fig. 5.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography at 3 months after withdrawal of pazopanib showed marked improvement in the small bowel wall

Discussion

Intestinal lymphangiectasia is a rare disease characterized by dilatation of the intestinal lymphatics and loss of lymph fluid into the gastrointestinal tract, leading to hypoproteinemia, edema, lymphocytopenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. Endoscopic abnormalities are obvious and include scattered white spots and white swollen villi corresponding to marked dilation of the lymphatics within the intestinal mucosa [2]. Small bowel biopsy is necessary for diagnosis [3]. Histological examination confirms dilated mucosal and submucosal lymphatic vessels [4]. CT findings show thickening of the small bowel wall with submucosal edema [3]. In the present case, endoscopic, histologic, and CT examinations showed characteristic findings, and the patient was diagnosed with intestinal lymphangiectasia.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia is thought to be caused by blockage of the lymphatic flow, which may occur for various reasons. Primary is thought to be caused by congenital defects that affect the formation of lymphatic vessels. Secondary is thought to be caused by other underlying conditions that increase the pressure within the lymphatic vessels, such as intra-abdominal infections, tumors, or cirrhosis. However, in the absence of these underlying diseases, even secondary, much of the etiology of intestinal lymphangiectasia is currently unknown. Hokari et al. [2] reported that the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3) and lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1 was increased on the intestinal mucosal surface and decreased in the deep mucosal layer in patients with intestinal lymphangiectasia.

We believe that the clinical course of our patient indicates that pazopanib plays an important role in the development of intestinal lymphangiectasia. A review of molecularly targeted drugs showed the possible development of intestinal lymphangiectasia in patients taking pazopanib or axitinib [5]. Pazopanib is a multikinase inhibitor with VEGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and Kit as its target molecules, and these effects may have caused the development of intestinal lymphangiectasia in the present case.

Notably, not all patients treated with multikinase inhibitors develop intestinal lymphangiectasia. The reason for the development of lymphangiectasia of the small intestine in the present case may be that pazopanib is considered to have relatively few adverse effects among multikinase inhibitors and can be taken for a long time. In fact, our patient had been taking pazopanib for 4 years before the onset of intestinal lymphangiectasia, and he was a long-term drug user. In contrast, Motzer et al. [1] reported that the median duration of treatment with pazopanib was 8 months and that the progression-free survival duration was 8.4 months. It is possible that the disease developed as a result of a decrease in the inhibitory effect of VEGFR3 secondary to changes in drug sensitivity following long-term drug administration. The patient’s clinical course showed that a partial response was maintained in many metastatic lesions, but the bilateral femoral metastatic lesions tended to increase in size.

In conclusion, in patients with general malaise, hypoalbuminemia, and anemia despite normal endocrine function, it is necessary to consider the possibility that small intestinal lymphangiectasia may have developed during long-term treatment with multikinase inhibitors. In addition, we believe that clinicians should pay attention to the presence of characteristic thickening of the small intestinal wall on CT images in patients who have been taking multikinase inhibitors for a long time.

Acknowledgements

We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- CT

Computed tomography

- CECT

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that there are no known conflicts of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hokari R, Kitagawa N, Watanabe C, et al. Changes in regulatory molecules for lymphangiogenesis in intestinal lymphangiectasia with enteric protein loss. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nay J, Menias CO, Mellnick VM, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic disease: a multimodality review. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1926–1943. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang ST, Menias CO, Lubner MG, et al. Molecular and clinical approach to intra-abdominal adverse effects of targeted cancer therapies. Radiographics. 2017;37:1461–1482. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]