To the Editor:

In the United States, 131,512 pregnant and peripartum women have been affected by coronavirus disease (COVID-19), with 200 associated deaths (0.15%) (1). The hormonal, physiological, and immunomodulatory changes during pregnancy increase susceptibility to respiratory infections and may predispose women to more severe presentations of COVID-19 (2). COVID-19 in pregnant or peripartum women is associated with higher risk for preterm birth, preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and perinatal death and higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) when compared with pregnant or peripartum women without COVID-19 or when compared with nonpregnant women with COVID-19 (2–4). Venovenous (VV) ECMO is an invasive strategy to support oxygenation and ventilation for respiratory failure when conventional therapies have failed. We investigated the survival and complications of pregnant and/or peripartum women with COVID-19 supported with VV ECMO reported to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry.

This retrospective cohort study included all adult women (⩾18 yr) supported on VV ECMO with COVID-19 between January 2020 and April 2021 reported to the ELSO Registry, representing 213 international centers in 36 countries. The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge, and secondary outcomes were ECMO-related complications in the pregnant and/or peripartum cohort. Pregnant state was collected in the ELSO COVID-19 addendum as a comorbidity. Comorbidities and ECMO-related complications were defined according to ELSO data definitions. This study was granted an exemption by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. We compared pregnant and peripartum patients with the nonpregnant female cohort with categorical variables as exact numbers with percentages and continuous variables as median values with interquartile ranges. Categorical data were analyzed with Fisher’s exact or Pearson’s chi-square and continuous variables with the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Overlap propensity score weighting was performed to investigate the effects of pregnancy on outcomes while adjusting for bias due to potential confounders. Propensity scores for patients being pregnant were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model with a priori identified factors (race, age, pre-ECMO cardiac arrest, admission time to ECMO initiation, driving pressure, mean airway pressure, pH, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, asthma, chronic heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, overweight/obesity, disseminated intravascular coagulation, neurological disease, chronic kidney disease, acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, heart failure, myocarditis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, septic shock, nonpulmonary infections, pulmonary vasodilators, buffering agents, and renal replacement therapy). Then, overlap propensity score–weighted logistic regression models were used to compare outcomes between pregnant and nonpregnant patients, in which each patient is weighted by the probability of belonging to the opposite status of her pregnancy (5). Bonferroni correction was used to correct for 10 outcomes in the propensity score analysis, leading to statistical significance if a P value < 0.05/10 = 0.005.

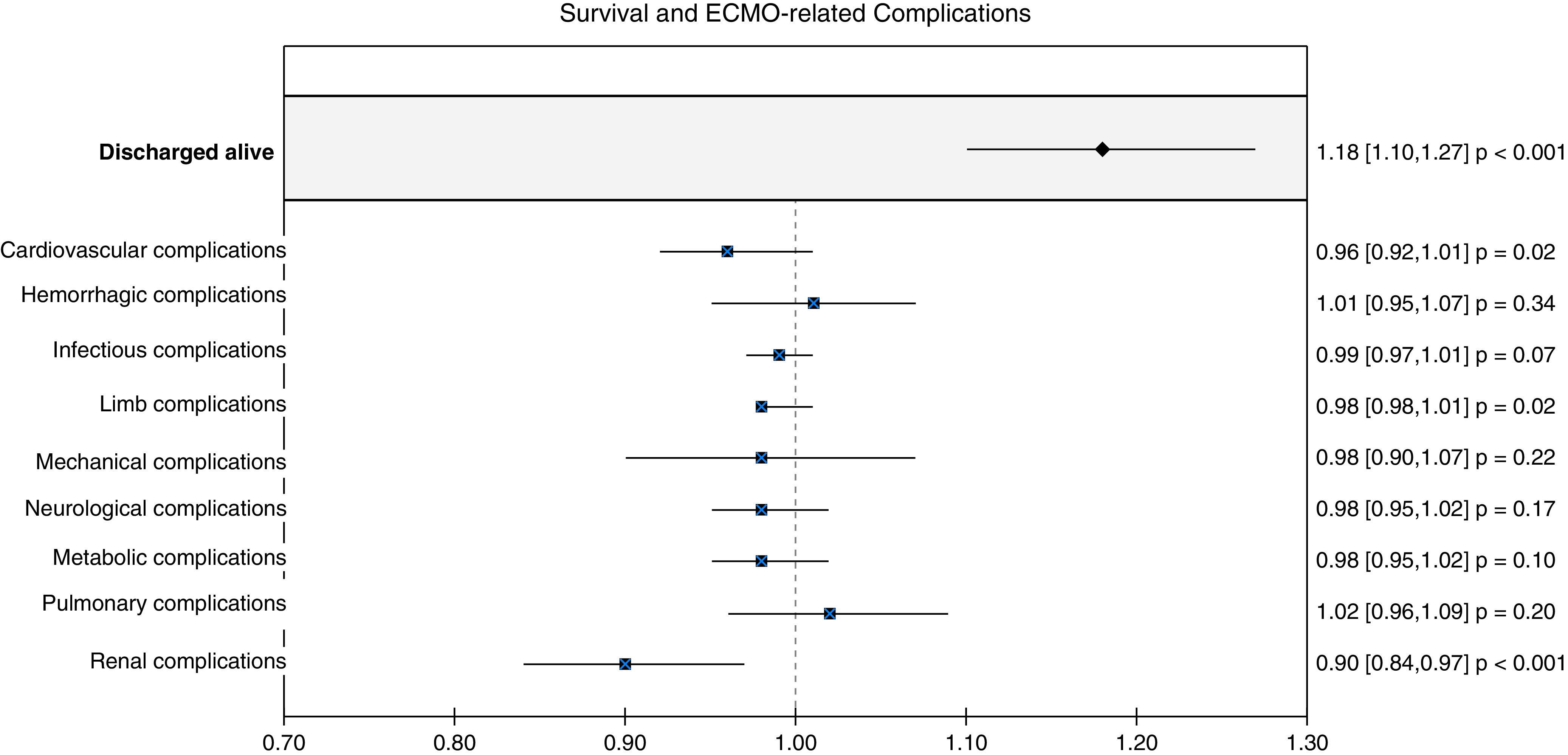

There were 1,180 adult female patients supported with VV ECMO for COVID-19, of whom 100 were pregnant or peripartum patients. Univariate analysis showed that pregnant or peripartum patients were younger (32.4 vs. 49.3 yr; P < 0.01) and more commonly Hispanic (27.0% vs. 20.7%; odds ratio [OR], 2.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30–4.2), Black (19.0% vs. 16.7%; OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.08–3.87), or Asian (13.0% vs. 8.4%; OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.34–5.69) (Table 1). Nonpregnant patients were more likely to have comorbidities. The majority of patients in both groups were proned before ECMO. There were no differences in pre-ECMO status or ECMO duration (Table 1). Comparing the pregnant and/or peripartum cohort with the propensity score–adjusted comparator cohort, the pregnant or peripartum group were more likely to survive to hospital discharge (84% vs. 51.5%; overlap propensity score–weighted OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.10–1.27) and suffered fewer ECMO-related renal complications (overlap propensity score–weighted OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84–0.97) (Figure 1). There were no other ECMO-related complication differences between cohorts.

Table 1.

Demographics, Comorbidities, Pre-ECMO Support, and ECMO Run Variables of Pregnant or Peripartum and Nonpregnant Women Supported on VV ECMO for COVID-19

| All Pregnant or Peripartum Patients (N = 100) | All Nonpregnant Female Patients (N = 1,080) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 32.4 (28.4–36.8) | 49.3 (40.6–57.6) | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 85.0 (71.4–104.5) | 92.0 (77.7–111.0) | 0.02 |

| Overweight or obesity | 53 (53.0) | 735 (68.1) | <0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 22 (22.0) | 426 (39.4) | Reference |

| Hispanic | 27 (27.0) | 224 (20.7) | 0.005 |

| Black | 19 (19.0) | 180 (16.7) | 0.03 |

| Asian | 13 (13.0) | 91 (8.4) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Asthma | 15 (15.0) | 219 (20.3) | 0.24 |

| Malignancy | 0 | 27 (2.5) | 0.11 |

| Immunocompromised | 0 | 79 (7.3) | <0.01 |

| Chronic heart disease | 1 (1.0) | 26 (2.4) | 0.37 |

| Hypertension | 20 (20.0) | 392 (36.3) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure | 5 (5.0) | 35 (3.2) | 0.35 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0 | 48 (4.4) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 20 (20.0) | 362 (33.5) | <0.01 |

| Neurological disease | 11 (11.0) | 121 (11.2) | 0.95 |

| DIC | 3 (3.0) | 15 (1.4) | 0.21 |

| ARDS | 80 (80.0) | 910 (84.3) | 0.27 |

| Pneumonia | 61 (61.0) | 665 (61.6) | 0.91 |

| Pneumothorax | 14 (14.0) | 128 (11.9) | 0.53 |

| Septic shock | 24 (24.0) | 282 (26.1) | 0.64 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 1 (1.0) | 31 (2.9) | 0.27 |

| Acute kidney failure | 13 (13.0) | 271 (25.1) | <0.01 |

| Pre-ECMO support | |||

| Invasive ventilation: PEEP, cm H2O | 14 (12–16) (n = 89) | 14 (11–16) (n = 927) | 0.97 |

| Invasive ventilation: PIP, cm H2O | 35 (31–38) (n = 70) | 34 (31–39) (n = 730) | 0.92 |

| Invasive ventilation: MAP, cm H2O | 23 (19–26) (n = 55) | 22 (19–25) (n = 577) | 0.76 |

| Invasive ventilation: driving pressure, cm H2O | 21 (28–26) (n = 70) | 21 (17–25) (n = 709) | 0.55 |

| PF ratio | 68 (57–87) (n = 87) | 70 (57–91) (n = 876) | 0.55 |

| Any pulmonary vasodilators | 33 (33.0) | 376 (34.8) | 0.72 |

| Neuromuscular blockers | 71 (71.0) | 823 (76.2) | 0.25 |

| Prone positioning | 58 (58.0) | 627 (58.1) | 0.99 |

| Intubation to ECMO initiation, h | 97 (25–187) (n = 87) | 77 (25–149) (n = 933) | 0.30 |

| Pre-ECMO cardiac arrest | 3 (3.0) | 29 (2.7) | 0.90 |

| ECMO run | |||

| Hours ECMO | 396 (219–735) | 401 (211–688) (n = 1,080) | 0.65 |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MAP = mean airway pressure; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure; PF = PaO2/FiO2; PIP = peak inspiratory pressure; VV ECMO = venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Data are shown as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Figure 1.

Survival and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)-related complications of the propensity score–matched cohorts, comparing the pregnant and peripartum patients with the nonpregnant female patients. Pregnant and peripartum patients had higher survival (overlap propensity score–weighted odds ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.10–1.27) and suffered fewer ECMO-related renal complications (overlap propensity score–weighted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.84–0.97) than the nonpregnant group.

Pregnant and peripartum women with COVID-19 have increased morbidity, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, need for ECMO support, and mortality when compared with nonpregnant women with COVID-19 (2–4). The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine guidelines for the management of severe COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome endorses the use of ECMO for postpartum patients and pregnant women <32 weeks’ gestation with refractory hypoxemia, to facilitate in utero fetal development (6). The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends that ECMO should not be withheld from pregnant patients who may potentially benefit (6). Indeed, our study supports the use of VV ECMO in this population, with increased survival for pregnant and peripartum women with severe COVID-19 who received VV ECMO support compared with a propensity-matched cohort of VV ECMO–supported nonpregnant women with COVID-19.

We report that pregnant and peripartum women supported on ECMO for COVID-19 were more likely to be Hispanic, Black, or Asian when compared with the nonpregnant cohort. Severe maternal morbidity, or unexpected outcomes of pregnancy that result in short- or long-term health consequences, are more prevalent in non-Hispanic Black women and Hispanic women than in White women in the United States (7). During the pandemic, Black and Hispanic pregnant women were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 (4, 8). These racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality are evident in our study.

Pregnant and peripartum women were less likely to sustain renal complications than the women of reproductive age supported on ECMO in our study. Angiotensin II, progesterone, and increased nitric oxide, produced during pregnancy, increase renal plasma flow by decreasing vascular resistance, which may explain the lower rates of renal injury (9). Although previously considered higher-risk ECMO candidates, pregnant and peripartum women did not sustain more ECMO-related complications, consistent with other reports (10). Importantly, no pregnant or peripartum women sustained limb complications, despite the majority experiencing femoral vein cannulations. Lastly, these pregnant and peripartum women with COVID-19 sustained few bleeding complications and no more than their matched nonpregnant cohort, despite anticoagulation and pregnancy-related coagulation changes.

Our study has limitations. Retrospective, registry-based studies are at risk of selective reporting by centers. Unidentified confounders may be present, despite incorporating a propensity score analysis with overlap weighting by accounting for 28 variables. The pregnancy indicator in the ELSO COVID-19 addendum does not distinguish if actively pregnant or how many weeks postpartum. In addition, the outcomes of the pregnancy and outcomes beyond hospital discharge are not known.

The use of VV ECMO to support pregnant and peripartum women with respiratory failure from COVID-19 was associated with lower in-hospital mortality and ECMO-related renal complications than those in nonpregnant females. This vulnerable population should be considered for VV ECMO support for COVID-19.

Footnotes

Supported by internal funding.

Author Contributions: Study conception, design, material preparation, data collection, and statistical analysis were performed by M.M.A., E.R.O’N., H.L., P.R.R., and M.L. The first draft of the manuscript was written by E.R.O’N., and all authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2096LE on November 12, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2020https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fcases-updates%2Fspecial-populations%2Fpregnancy-data-on-covid-19.html#pregnant-population.

- 2. Dashraath P, Wong JLJ, Lim MXK, Lim LM, Li S, Biswas A, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2020;222:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: The INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr . 2021;175:817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, Galang RR, Oduyebo T, Tong VT, et al. CDC COVID-19 Response Pregnancy and Infant Linked Outcomes Team Update: characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas LE, Li F, Pencina MJ. Overlap weighting: a propensity score method that mimics attributes of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2020;323:2417–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Society for Maternal‐Fetal Medicine (SFMF) 2021. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2734/SMFM_COVID_Management_of_COVID_pos_preg_patients_2-2-21_(final).pdf

- 7. Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Zivin K, Terplan M, Mhyre JM, Dalton VK. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of severe maternal morbidity in the United States, 2012-2015. Obstet Gynecol . 2018;132:1158–1166. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grechukhina O, Greenberg V, Lundsberg LS, Deshmukh U, Cate J, Lipkind HS, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 pregnancy outcomes in a racially and ethnically diverse population. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM . 2020;2:100246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheung KL, Lafayette RA. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis . 2013;20:209–214. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barrantes JH, Ortoleva J, O’Neil ER, Suarez EE, Beth Larson S, Rali AS, et al. Successful treatment of pregnant and postpartum women with severe COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J . 2021;67:132–136. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]