Abstract

Objective:

To compare outcomes after surgery between patients who were not prescribed opioids and patients who were prescribed opioids.

Summary of Background Data:

Postoperative opioid prescriptions carry significant risks. Understanding outcomes among patients who receive no opioids after surgery may inform efforts to reduce these risks.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective study of adult patients who underwent surgery between January 1, 2019 and October 31, 2019. The primary outcome was the composite incidence of an emergency department visit, readmission, or reoperation within 30 days of surgery. Secondary outcomes were postoperative pain, satisfaction, quality of life, and regret collected via postoperative survey. A multilevel, mixed-effects logistic regression was performed to evaluate differences between groups.

Results:

In a cohort of 22,345 patients, mean age (SD) was 52.1 (16.5) years and 13,269 (59.4%) patients were female. 3,175 (14.2%) patients were not prescribed opioids. Patients not prescribed opioids had a similar probability of adverse events (11.7% [95% CI 10.2%−13.2%] vs. 11.9% [95% CI 10.6%−13.3%]). Among 12,872 survey respondents, patients who were not prescribed an opioid had a similar rate of high satisfaction (81.7% [95% CI 77.3%−86.1%] vs. 81.7% [95% CI 77.7%−85.7%]) and no regret (93.0% [95% CI 90.8%−95.2%] vs. 92.6% [95% CI 90.4%−94.7%]), and higher rates of best quality of life (65.9% [95% CI 61.3%−70.4%] vs. 63.1% [95% CI 58.4%−67.7%]) and no pain (11.5% [95% CI 8.8%−14.1%]) vs. 7.2% [95% CI 5.7%−8.7%]).

Conclusions:

Patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery had similar clinical and patient-reported outcomes as patients who were prescribed opioids. This suggests that minimizing opioids as part of routine postoperative care is unlikely to adversely affect patients.

Introduction

For decades, prescription opioids have been the mainstay for postoperative pain control in the United States.1 Unfortunately, patients exposed to opioids after surgery incur significant risks, including prolonged use, increased complications, and increased healthcare spending for months after surgery.2–6 Additionally, opioid prescriptions often result in leftover medication.7 Up to 90% of patients who receive an opioid prescription after surgery have leftover medication that remains undisposed.8 This excess supply creates a reservoir of opioids available for diversion and misuse.9

While reducing or even eliminating opioids as part of postoperative recovery would avoid all of these risks, such efforts are hindered by concerns of inadequate pain control which can lead to increased healthcare utilization.2,10,11 However, outside of the US, opioids are rarely used for postoperative pain control.12 A study comparing common surgical procedures internationally found that only 5% of patients in other countries received a postoperative opioid prescription compared to 90% of patients in the United States.13 Importantly, pain control was not compromised in regions where postoperative opioid prescribing was rare. A similar study of dentists found that opioid prescribing was 37 times greater in the US compared to prescribing in England.14 Although a handful of pilot efforts in the US have implemented “opioid-sparing recovery,” these efforts typically target only a few procedures, and it is unclear if this strategy could be replicated on a larger scale.15–17 Despite increasing awareness of the risks associated with opioids in the postoperative period, uncertainty around the feasibility of minimizing opioids after surgery has slowed efforts to mitigate these risks. Better understanding patient outcomes when surgeons do not prescribe any opioids after surgery may bolster efforts to further minimize their role postoperatively and may serve as an important complement to increasingly comprehensive patient education and multimodal analgesia regimens.

Within this context, we conducted the following study to compare patient outcomes after surgery between patients who were prescribed opioids after surgery with patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery. To accomplish this, we analyzed clinical and patient-reported outcomes using a clinically rich surgical registry to account for a number of patient and clinical characteristics that are known to be associated with postoperative opioid prescribing and use. Given the minimal use of opioids in other countries and the success of opioid-sparing recovery pathways, we hypothesized that patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery would have similar rates of adverse events, satisfaction, and pain control when compared to patients who were prescribed opioids.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan deemed this study exempt from regulation owing to secondary analysis of de-identified data. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.18

Data Source and Cohort Selection

We used a clinical registry maintained by the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) as our data source. The MSQC is a statewide quality improvement program made up of 70 participating hospitals in Michigan.19–23 Trained nurse abstractors perform chart review and collect data on patient demographics, perioperative processes of care, and 30-day outcomes for patients undergoing surgery at these hospitals.24 Cases are reviewed using a sampling algorithm that ensures a representative patient sample and minimizes selection bias.25 Data collection accuracy is audited annually.

Our cohort included all adult patients (18 years and older) who underwent one of seven surgical procedures during a 10-month period between January 1, 2019 and October 31, 2019. Surgical procedures included laparoscopic appendectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, colon and small bowel procedures, inguinal/femoral hernia repair, ventral/incisional hernia repair, laparoscopic hysterectomy, vaginal hysterectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and thyroidectomy. Patients were excluded if they died within 30 days of surgery, had a length of stay greater than 14 days, or were discharged to a destination other than home. Patients with missing explanatory or outcomes data were also excluded (Supplemental Table 1). Explanatory variables and clinical outcomes were obtained for the entire cohort, while complete patient-reported outcomes were available for a subset of patients who responded to a follow-up survey after surgery (12,872 patients [57.6%]). Postoperative surveys were administered by telephone, email, or mail between postoperative days 30–90 and sampling algorithms for survey administration were determined by each participating hospital’s nurse reviewer based on workload and feasibility.

Explanatory Variables

The primary explanatory variable was being prescribed an opioid after surgery (yes/no), which was ascertained from the medical record. For patients who did not receive an opioid prescription, this was specifically recorded by MSQC data abstractors as “no opioid prescription” prescribed at the time of discharge by verifying the electronic medical record. For patients who received an opioid prescription, median (and interquartile range [IQR]) prescription size is represented as oral morphine equivalents (OME).26

Other covariates included patient demographics, patient characteristics, and clinical characteristics. Demographic information included patient age, sex, race and ethnicity, and insurance type. Insurance type was categorized into 5 groups: private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured, and dual coverage of Medicare and Medicaid.27 Patient characteristics included American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, obesity, cancer, tobacco use in the year prior to surgery, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), hypertension, chronic steroid use, dialysis, functional status (independent vs. non-independent), and preoperative opioid use in the 30 days prior to surgery. Clinical characteristics included admission status, surgical priority, surgical approach, and procedure type.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of adverse events in the 30 days after discharge. This was a composite endpoint of either an emergency department (ED) visit, readmission, or reoperation. The incidence of each individual outcome is also reported. The Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System was used to assign the International Classification of Disease 10th Edition (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes associated with each individual outcome to one of the following categories: pain, gastrointestinal, infectious, hematologic, or other complication.28 The pain category included any diagnostic code for pain. The gastrointestinal complication category included complications such as obstruction, ileus, hernia, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, ulcer disease, pancreatobiliary complications, and other gastrointestinal complications. Infectious complications included infection of any organ system. Hematologic complications included hemorrhage, hematoma, and anemia. The other category included an array of diagnoses of the cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, respiratory, gynecologic, musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, and skin/soft tissue organ systems, as well as traumatic injury.

Secondary outcomes were patient-reported outcomes including postoperative pain in the first seven days after discharge, satisfaction with care, quality of life, and regret to undergo surgery. Due to significant skew, patient-reported outcome scores were dichotomized according to methods employed in national patient satisfaction surveys such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS).29,30 Postoperative pain was measured on a scale of 1–4 (1=no pain, 2=minimal pain, 3=moderate pain, 4=severe pain) and dichotomized into “no pain” for a score of 1 and “some pain” for scores of 2–4. Satisfaction with care was measured from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied) and was dichotomized into “highly satisfied” for scores of 9–10 and “not highly satisfied” for scores of 0–8. Quality of life was measured from 1 (worst possible quality of life) to 5 (best possible quality of life) and dichotomized into “best possible quality of life” for a score of 5 and “less than best possible quality of life” for scores of 1–4. Lastly, regret to undergo surgery was measured from 1 (absolutely regret surgery) to 5 (absolutely no regret) and was dichotomized into “no regret” for a score of 5 and “some regret” for scores of 1–4.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic, patient, and clinical characteristics for patients based on receipt of an opioid prescription after surgery. Univariate differences between the two groups were calculated using the Chi-squared test. To address patient clustering within surgeons and surgeons clustering within hospitals, a multilevel, mixed-effects logistic regression, with hospital and surgeon included as random intercepts, was performed to evaluate differences in adverse events between patients who were prescribed opioids after surgery and patients not prescribed opioids after surgery while controlling for demographics, patient characteristics, and clinical characteristics. Because preoperative opioid use has been shown to be associated with surgeon prescribing practice, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis excluding this group of patients.31 All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.1. P values were 2-tailed and significance was set at α=0.05.

Results

22,345 patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the primary analysis. Mean age (SD) of the cohort was 52.1 (16.5) years and 13,269 (59.4%) patients were female. A majority of patients were white (18,067, 80.9%) and had private insurance (11,710, 52.4%). 3538 (15.8%) patients used opioids in the 30-days prior to surgery. Most operations were performed on an elective basis in an inpatient setting. Full demographic and clinical characteristics including procedure type are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 –

Cohort Characteristics

| No. (col %) | No. (row %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 22345) |

No Prescription (N = 3175) |

Prescription (N = 19170) |

P |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 2329 (10.4) | 227 (9.7) | 2102 (90.3) | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 3204 (14.3) | 296 (9.2) | 2908 (90.8) | |

| 40–49 | 4371 (19.6) | 457 (10.5) | 3914 (89.5) | |

| 50–59 | 4455 (19.9) | 584 (13.1) | 3871 (86.9) | |

| 60–64 | 2305 (10.3) | 350 (15.2) | 1955 (84.8) | |

| ≥65 | 5681 (25.4) | 1261 (22.2) | 4420 (77.8) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 9076 (40.6) | 1255 (13.8) | 7821 (86.2) | 0.183 |

| Female | 13269 (59.4) | 1920 (14.5) | 11349 (85.5) | |

| Race | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 18067 (80.9) | 2718 (15.0) | 15349 (85.0) | <0.001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2226 (10.0) | 213 (9.6) | 2013 (90.4) | |

| Hispanic | 585 (2.6) | 49 (8.4) | 536 (91.6) | |

| Other | 1467 (6.6) | 195 (13.3) | 1272 (86.7) | |

| Insurance Type | ||||

| Private | 11710 (52.4) | 1276 (10.9) | 10434 (89.1) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 5807 (26.0) | 1309 (22.5) | 4498 (77.5) | |

| Medicaid | 4023 (18.0) | 448 (11.1) | 3575 (88.9) | |

| Dual Medicare/Medicaid | 407 (1.8) | 75 (18.4) | 332 (81.6) | |

| No Insurance | 398 (1.8) | 67 (16.8) | 331 (83.2) | |

| ASA Classification | ||||

| Class 1 | 1858 (8.3) | 205 (11.0) | 1653 (89.0) | <0.001 |

| Class 2 | 12765 (57.1) | 1560 (12.2) | 11205 (87.8) | |

| Class 3 | 7354 (32.9) | 1315 (17.9) | 6039 (82.1) | |

| Class 4–5 | 368 (1.6) | 95 (25.8) | 273 (74.2) | |

| Preoperative Opioid Use | 3538 (15.8) | 746 (21.1) | 2792 (78.9) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 10472 (46.9) | 1350 (12.9) | 9122 (87.1) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1516 (6.8) | 344 (22.7) | 1172 (77.3) | <0.001 |

| Cigarette Use | 4870 (21.8) | 601 (12.3) | 4269 (87.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2602 (11.6) | 465 (17.9) | 2137 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Non-Independent | 134 (0.6) | 45 (33.6) | 89 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 932 (4.2) | 183 (19.6) | 749 (80.4) | <0.001 |

| CHF | 46 (0.2) | 10 (21.7) | 36 (78.3) | 0.210 |

| Hypertension | 8245 (36.9) | 1381 (16.7) | 6864 (83.3) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Steroid Use | 520 (2.3) | 108 (20.8) | 412 (79.2) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 74 (0.3) | 19 (25.7) | 55 (74.3) | 0.008 |

| Inpatient Admission | 11783 (52.7) | 2250 (19.1) | 9533 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Non-Elective Surgery | 5754 (25.8) | 1236 (21.5) | 4518 (78.5) | <0.001 |

| Surgical Approach | ||||

| Minimally Invasive | 16017 (71.7) | 2167 (13.5) | 13850 (86.5) | <0.001 |

| Open | 6328 (28.3) | 1008 (15.9) | 5320 (84.1) | |

| Procedure | ||||

| Laparoscopic Appendectomy | 2420 (10.8) | 415 (17.1) | 2005 (82.9) | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy | 6197 (27.7) | 844 (13.6) | 5353 (86.4) | |

| Colon/Small Bowel | 2321 (10.4) | 696 (30.0) | 1625 (70.0) | |

| Inguinal/Femoral Hernia Repair | 3717 (16.6) | 344 (9.3) | 3373 (90.7) | |

| Ventral/Incisional Hernia Repair | 2985 (13.4) | 286 (9.6) | 2699 (90.4) | |

| Laparoscopic Hysterectomy | 2305 (10.3) | 235 (10.2) | 2070 (89.9) | |

| Vaginal Hysterectomy | 1083 (4.8) | 145 (13.4) | 938 (86.6) | |

| Total Abdominal Hysterectomy | 788 (3.5) | 60 (7.6) | 728 (92.4) | |

| Thyroidectomy | 529 (2.4) | 150 (28.4) | 379 (71.6) | |

3,175 (14.2%) were not prescribed opioids at discharge. Among the 19,170 (85.8%) patients prescribed an opioid after surgery, median prescription size was 75 (IQR 50–100) mg OME, which is equivalent to 10 (IQR 6.7–13.3) tablets of oxycodone 5 mg or 15 (IQR 10–20) tablets of hydrocodone 5 mg. On univariate comparison, not receiving an opioid prescription was more common among older patients, white patients, patients with Medicare, and patients with preoperative opioid use. Opioid prescriptions also varied by different comorbidities and were less commonly provided for patients undergoing inpatient surgery, patients undergoing urgent/emergent procedures, and patients undergoing open procedures.

Primary Outcomes

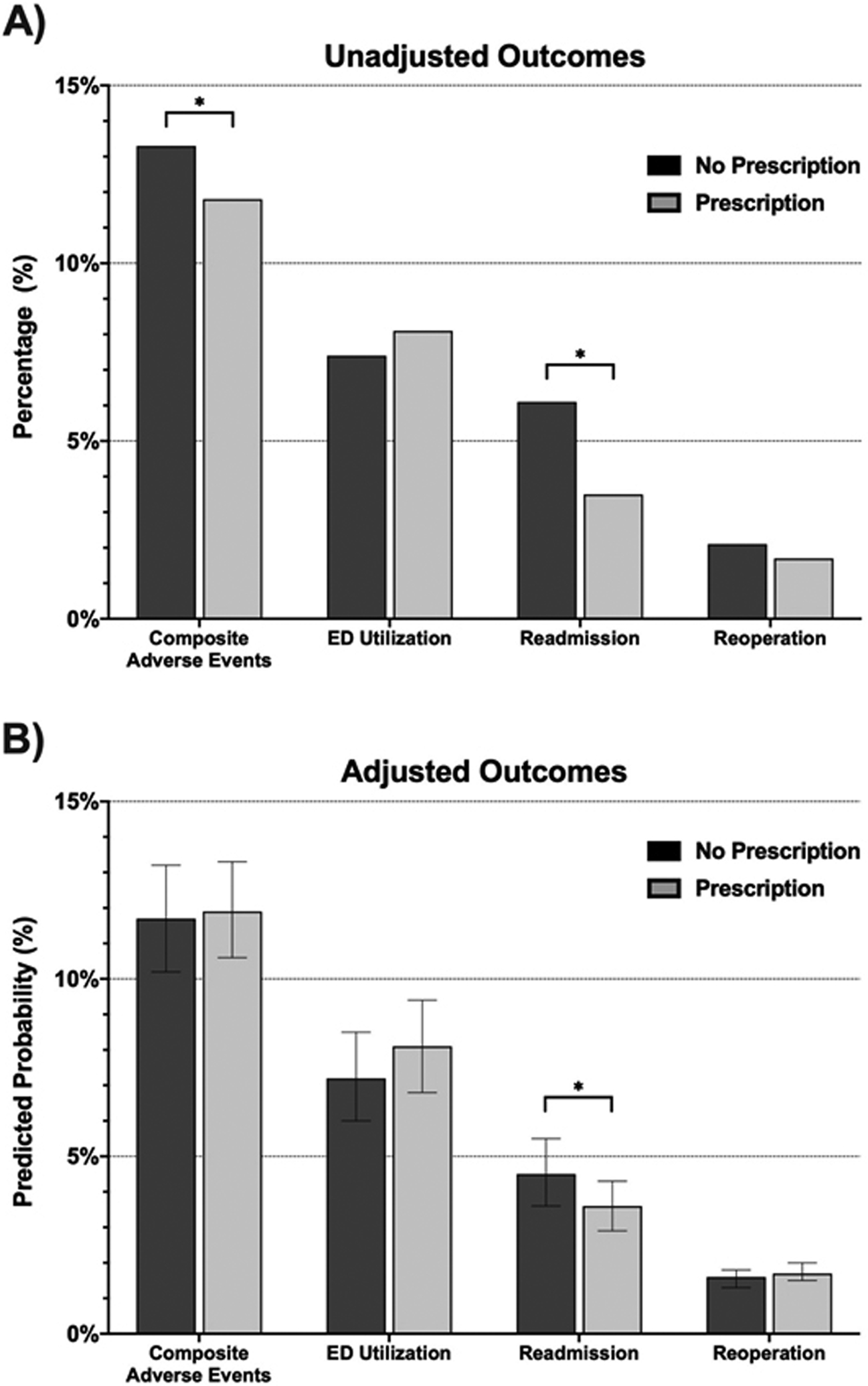

Overall, 2,677 (12.0%) patients met the composite endpoint after discharge, of whom 422 were not prescribed opioids. After adjusting for differences in patient severity, clinical differences, and hospital and surgeon variation between groups, there was no significant difference in the predicted probability of events between patients who were not prescribed opioids (11.7% [95% CI 10.2%−13.2%]) and patients who were prescribed opioids (11.9% [95% CI 10.6%−13.3%], P=0.724) (Figure 1). Regarding individual outcomes, there was also no significant difference in the predicted probability of ED utilization (7.2% [95% CI 6.0%−8.5%] vs. 8.1% [95% CI 6.8%−9.4%], P=0.100) or reoperation (1.6% [95% CI 1.3%−1.8%] vs. 1.7% [95% CI 1.5%−2.0%], P=0.504). The predicted probability of readmission was higher among patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery (4.5% [95% CI 3.6%−5.5%] vs. 3.6% [95% CI 2.9%−4.3%], P=0.010).

Figure 1 –

Primary Outcomes – A) unadjusted and B) adjusted 30-day clinical outcomes among the entire patient cohort (22,345).

Among patients who experienced one of these clinical outcomes, there was no significant difference in the associated diagnoses based on opioid prescription (Table 2). Specifically, there was no difference in the proportion of patients with a pain-related diagnostic code for ED utilization (67 [28.3%] vs. 529 [34.0%], P=0.088), readmission (20 [10.3%] vs. 69 [10.4%], P=0.947), and reoperation (1 [1.5%] vs. 4 [1.2%], P=0.853).

Table 2 –

Diagnostic categories associated with individual 30-day outcomes.

| ED Utilization (N (%)) | Readmission (N (%)) | Reoperation (N (%)) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication Category | No Opioid Prescription | Opioid Prescription | P | No Opioid Prescription | Opioid Prescription | P | No Opioid Prescription | Opioid Prescription | P |

| Pain | 67 (28.3) | 529 (34.0) | 0.088 | 20 (10.3) | 69 (10.4) | 0.947 | 1 (1.5) | 4 (1.2) | 0.853 |

| Gastrointestinal | 33 (14.0) | 162 (10.4) | 0.101 | 49 (25.1) | 178 (26.9) | 0.549 | 31 (45.6) | 130 (38.9) | 0.307 |

| Infectious | 15 (6.4) | 126 (8.1) | 0.354 | 47 (24.1) | 147 (22.2) | 0.578 | 4 (5.9) | 39 (11.7) | 0.159 |

| Hematologic | 9 (3.8) | 45 (2.9) | 0.440 | 11 (5.6) | 41 (6.2) | 0.777 | 12 (17.6) | 39 (11.7) | 0.178 |

| Other | 112 (47.5) | 694 (44.6) | 0.412 | 68 (34.9) | 227 (34.3) | 0.881 | 20 (29.4) | 122 (36.5) | 0.263 |

The pain category included any diagnostic code for pain. The gastrointestinal complication category included complications such as obstruction, ileus, hernia, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, ulcer disease, pancreatobiliary complications, and other gastrointestinal complications. Infectious complications included infection of any organ system. Hematologic complications included hemorrhage, hematoma, and anemia. Lastly, the other category included an array of other diagnoses of the cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, respiratory, gynecologic, musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, and skin/soft tissue organ systems, as well as traumatic injury

Secondary Outcomes

12,872 (57.6%) patients had complete follow-up survey data. There was no difference between survey respondents and non-respondents in the proportion of patients who were not prescribed opioids (1781 [13.8%] vs. 1394 [14.7%], P=0.066). Univariate comparisons of respondents and non-respondents are presented in Supplemental Table 1. A total of 1024 (8.0%) patients reported no pain in the first 7-days after discharge, 10,511 (81.7%) patients reported high satisfaction, 8168 (63.5%) patients reported best possible quality of life, and 11917 (92.6%) patients reported no regret to undergo surgery (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the predicted probability of being highly satisfied (81.7% [95% CI 77.3%−86.1%] vs. 81.7% [95% CI 77.7%−85.7%], P=0.972) or having no regret (93.0% [95% CI 90.8%−95.2%] vs. 92.6% [95% CI 90.4%−94.7%], P=0.509) between the groups. Not receiving an opioid prescription was associated with a higher predicted probability of reporting no pain in the week following discharge (11.5% [95% CI 8.8%−14.1%] vs. 7.2% [95% CI 5.7%−8.7%], P<0.001) and reporting best possible quality of life (65.9% [95% CI 61.3%−70.4%] vs. 63.1% [95% CI 58.4%−67.7%], P=0.022).

Table 3 –

Secondary Outcomes – unadjusted and adjusted 30–90-day patient-reported outcomes among patients who responded to postoperative surveys (12,872 patients).

| Secondary Outcome | Unadjusted Outcomes (N (%)) |

Adjusted Outcomes (Predicted Probability (% (95% CI))) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Prescription | Prescription | P | No Prescription | Prescription | P | |

| No Pain | 249 (14.0) | 775 (7.0) | <0.001 | 11.5 (8.8–14.1) | 7.2 (5.7–8.7) | <0.001 |

| Highly Satisfied | 1456 (81.8) | 9055 (81.6) | 0.938 | 81.7 (77.3–86.1) | 81.7 (77.7–85.7) | 0.972 |

| Best Possible QOL | 1122 (63.0) | 7046 (63.5) | 0.685 | 65.9 (61.3–70.4) | 63.1 (58.4–67.7) | 0.022 |

| No Regret | 1662 (93.3) | 10255 (92.5) | 0.218 | 93.0 (90.8–95.2) | 92.6 (90.4–94.7) | 0.509 |

Unadjusted outcomes presented as proportion of patients in each group. Adjusted outcomes estimated using multilevel, mixed-effect logistic regression adjusting for all patient and clinical characteristics from Table 1, as well as random effects at the hospital- and surgeon-level.

Sensitivity Analysis

Results after excluding 3,538 patients preoperative opioid use were similar to the main analysis (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Specifically, there was no difference in the predicted probability of the composite endpoint between groups (10.8% [95% CI 9.1–12.5%] vs. 11.1% [95% CI 9.6%−12.7%], P=0.672), however the predicted probability of readmission was higher among patients not prescribed opioids (4.3% [95% CI 3.1%−5.5%] vs. 3.2% [95% CI 2.4%−4.1%], P=0.009).

Discussion

In this large observational study of patients undergoing common surgical procedures, 14.2% of patients were not prescribed opioids after surgery. After accounting for differences in patient severity and clinical characteristics, there was no difference in the overall rate of adverse events after discharge between patients who were not prescribed opioids and those who were. Patients who were and were not prescribed opioids were similarly likely to be highly satisfied, to report the best quality of life, and to not regret undergoing surgery. Additionally, patients who were not prescribed opioids had less pain than patients prescribed opioids after surgery. This suggests that patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery did not experience worse short-term outcomes compared to patients who were prescribed opioids. Going forward, decreasing or even eliminating opioids as part of routine postoperative care could mitigate the risks they pose – including overdose, diversion, and persistent opioid use – without compromising patient outcomes.

It has become increasingly clear that prescribing opioids to patients after surgery can have lasting negative consequences.1,3,4,32,33 However, an important limitation in studying the association of opioid prescriptions with patient outcomes is the presence of confounding factors. The decision to prescribe or not prescribe opioids to a patient is influenced by many factors that are unavailable in administrative claims analysis.34,35 For example, surgeons may be less likely to prescribe opioids to frail, comorbid patients for fear of complications in this population, but those specific patient risk factors may confound analysis of any outcomes related to opioid prescribing. The current study partly addresses this by including and adjusting for a number of relevant patient and clinical characteristics using a clinically rich data set. Importantly, it also analyzes actual prescription of an opioid whereas claims data is limited to whether a patient filled an opioid prescription around the time of surgery, which may not accurately reflect surgeon practice and may be unrelated to their operation. After accounting for differences in patient age, sex, preoperative opioid use, comorbidities, and clinical details, we did not observe any difference in the overall incidence of adverse events or inferior patient-reported outcomes among patients not prescribed opioids. Other approaches can be used to adjust for confounding, such as propensity-score matching, where groups are matched in such a way that the only significant difference between groups is the variable under investigation. However, this approach often produces similar results to regression analysis and in some cases results in a lack of power to detect a treatment effect due to its exclusion of cases until both groups are balanced.36,37

A barrier to minimizing the role of opioids in the postoperative period has been concern that this would lead to inferior patient outcomes. Some studies have shown that opioid prescriptions are associated with increased satisfaction and that greater postoperative pain is associated with increased ED utilization.38 The current study, however, suggests that the absence of an opioid prescription following surgery is not associated with inferior patient-reported outcomes.16,39 What’s more, these findings are consistent with those of other studies investigating the impact of opioid-sparing postoperative recovery on patient outcomes. Hallway et al. surveyed patients participating in an opioid-sparing postoperative recovery pathway after surgery and found that median opioid use was 0 pills, median satisfaction score was 10 out of 10, and 91% of patients agreed that their pain was manageable using this regimen.40 Anderson et al. similarly analyzed patient-reported outcomes among patients undergoing common surgical procedures and found that, after propensity-score matching patients in an opioid-sparing recovery protocol with patients receiving usual care, there was no difference in satisfaction, quality of life, or regret to undergo surgery between the two groups.41 The current study adds to this evidence by demonstrating that even in the most extreme case – not receiving an opioid prescription at all – patients do not report worse satisfaction, quality of life, regret to undergo surgery, or pain.

On some patient-reported outcomes, patients who did not receive an opioid prescription fared better than those who received an opioid prescription. For example, among the former, there was both a higher unadjusted incidence (14.0% vs. 7.0%) and predicted probability (11.5% vs. 7.2%) of reporting no pain. This may be related to surgeons modifying their prescribing practices based on factors leading them to believe the patient will have little to no pain after surgery. For example, it has been previously demonstrated that operative time and case complexity is associated with postoperative opioid prescription size.7,42 Therefore, low case complexity, short incision length, or patient preference to avoid opioids may explain why patients who did not receive a prescription had less pain overall. Conversely, patients undergoing longer, more complex operations may both have more pain and be more likely to receive a larger prescription. Given that these confounding intraoperative details are directly measurable, additional work is needed to understand how these factors might enable surgeons to identify patients who may not require a postoperative opioid prescription.

While the composite clinical outcome was similar between groups, there were nevertheless differences in individual outcomes to consider. For example, not receiving an opioid prescription was associated with a higher incidence of hospital readmission in both the main and sensitivity analysis. Other studies have actually demonstrated the opposite to be the case, such that patients receiving a postoperative opioid prescription were at increased risk of hospital readmission.43 While the modeling used in this study controlled for factors such as opioid use in the 30-days prior to surgery, a higher prevalence of chronic (>30 days) preoperative opioid use among patients who did not receive a prescription may explain the higher readmission rate. Patients with a history of chronic opioid use are both less likely to receive an opioid prescription and be readmitted to the hospital after surgery.44–46 This difference highlights the need for even further analysis of patient characteristics that may confound receipt of an opioid prescription, such as pain disorders or insurance characteristics.

This study is not without important limitations. Despite our use of multilevel logistic regression modeling, the potential for unobserved confounding still remains insofar as certain intraoperative and preoperative details were not included in this data set. As mentioned, intraoperative details such as case complexity, extent of surgical dissection, and incision length likely play a role in the decision to prescribe opioids. Nevertheless, discriminating by overall procedure type still allowed us to control for general differences between individual operations. This study also lacks certain preoperative patient characteristics such as chronic pain diagnoses, preoperative pain levels, and socioeconomic status, all of which have been shown to be associated with prescribing patterns and use. While our inclusion of insurance type serves to some extent as a surrogate for socioeconomic differences between patients, additional research is needed to further understand the effect of these critical patient characteristics on prescribing and patient-reported outcomes. The self-reported nature of the secondary results of this study are also limited by the presence of bias affecting survey research, including self-selection, loss-to-follow-up, and recall bias, although we note a relatively high response rate of 57.6%. Insofar as there were differences between respondents and non-respondents, it is equally important to understand whether patient-reported outcomes differed for patients who did not respond to follow-up surveys. Lastly, the current study only describes differences in 30-day clinical outcomes and 30–90-day patient-reported outcomes following surgery. Important opioid-related outcomes such as chronic dependence can unfold over months to years. While understanding long-term differences between these groups ought to be pursued in future work, we believe this study still characterizes a time period that many surgeons consider when making the decision to prescribe opioids postoperatively.

Conclusion

In a large cohort of patients undergoing common surgical procedures, 14% of patients were not prescribed an opioid after surgery. For these patients, the probability of a composite measure of adverse clinical events was similar to patients who were prescribed opioids after surgery, and patient-reported outcomes were either the same or better. Given the significant risks posed by opioids in the postoperative period, these results support the feasibility of reducing or potentially even eliminating opioids as part of routine postoperative pain control.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures:

RH receives funding for research from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5T32DK108740-05). CSB is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Award administered by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F32-DA050416). YL and VG have no disclosures. CB, ME, JW, and MB receive funding from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042859). Dr. Bicket reports past consultation with Axial Healthcare and Alosa Health not related to this work. No funder or sponsor had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. YL and VG had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Hah JM, Bateman BT, Ratliff J, Curtin C, Sun E. Chronic Opioid Use After Surgery: Implications for Perioperative Management in the Face of the Opioid Epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1733–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cozowicz C, Olson A, Poeran J, et al. Opioid prescription levels and postoperative outcomes in orthopedic surgery. Pain. 2017;158(12):2422–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JS, Vu JV, Edelman AL, et al. Health Care Spending and New Persistent Opioid Use After Surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brescia AA, Waljee JF, Hu HM, et al. Impact of Prescribing on New Persistent Opioid Use After Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108(4):1107–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of Opioid Prescribing With Opioid Consumption After Surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):e184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription Opioid Analgesics Commonly Unused After Surgery: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipari RN, Hughes A. How People Obtain the Prescription Pain Relievers They Misuse. In: The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD)2013:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies B, Brummett CM. Anchoring to Zero Exposure: Opioid-free Minimally Invasive Surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;271(1):37–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez-Boussard T, Graham LA, Desai K, et al. The Fifth Vital Sign: Postoperative Pain Predicts 30-day Readmissions and Subsequent Emergency Department Visits. Ann Surg. 2017;266(3):516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ladha KS, Neuman MD, Broms G, et al. Opioid Prescribing After Surgery in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaafarani HMA, Han K, El Moheb M, et al. Opioids After Surgery in the United States Versus the Rest of the World: The International Patterns of Opioid Prescribing (iPOP) Multicenter Study. Ann Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suda KJ, Durkin MJ, Calip GS, et al. Comparison of Opioid Prescribing by Dentists in the United States and England. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard R, Hallway A, Santos-Parker J, et al. Optimizing Postoperative Opioid Prescribing Through Quality-Based Reimbursement. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie CE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ Jr. Association of Decreased Postsurgical Opioid Prescribing With Patients’ Satisfaction With Surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1049–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs BL, Rogers D, Yabes JG, et al. Large reduction in opioid prescribing by a multipronged behavioral intervention after major urologic surgery. Cancer. 2021;127(2):257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birkmeyer NJ, Share D, Campbell DA Jr., Prager RL, Moscucci M, Birkmeyer JD. Partnering with payers to improve surgical quality: the Michigan plan. Surgery. 2005;138(5):815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell DA Jr., Kubus JJ, Henke PK, Hutton M, Englesbe MJ. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative: a legacy of Shukri Khuri. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englesbe MJ, Dimick JB, Sonnenday CJ, Share DA, Campbell DA Jr. The Michigan surgical quality collaborative: will a statewide quality improvement initiative pay for itself? Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):1100–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell DA Jr., Henderson WG, Englesbe MJ, et al. Surgical site infection prevention: the importance of operative duration and blood transfusion--results of the first American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Best Practices Initiative. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(6):810–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell DA Jr., Englesbe MJ, Kubus JJ, et al. Accelerating the pace of surgical quality improvement: the power of hospital collaboration. Arch Surg. 2010;145(10):985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healy MA, Regenbogen SE, Kanters AE, et al. Surgeon Variation in Complications With Minimally Invasive and Open Colectomy: Results From the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(9):860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gammaitoni AR, Fine P, Alvarez N, McPherson ML, Bergmark S. Clinical application of opioid equianalgesic data. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(5):286–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swenson CW, Kamdar NS, Levy H, Campbell DA Jr., Morgan DM. Insurance Type and Major Complications After Hysterectomy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(1):39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-PCS (beta version). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). November 2019. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp. Accessed February 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trout A, Magnusson AR, Hedges JR. Patient satisfaction investigations and the emergency department: what does the literature say? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(6):695–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aspinal F, Addington-Hall J, Hughes R, Higginson IJ. Using satisfaction to measure the quality of palliative care: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(4):324–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez NM, Parry JA, Mabry TM, Taunton MJ. Patients at Risk: Preoperative Opioid Use Affects Opioid Prescribing, Refills, and Outcomes After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7S):S142–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peahl AF, Dalton VK, Montgomery JR, Lai YL, Hu HM, Waljee JF. Rates of New Persistent Opioid Use After Vaginal or Cesarean Birth Among US Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waljee JF, Li L, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ. Iatrogenic Opioid Dependence in the United States: Are Surgeons the Gatekeepers? Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kopp JA, Anderson AB, Dickens JF, et al. Orthopedic Surgeon Decision-Making Processes for Postsurgical Opioid Prescribing. Mil Med. 2020;185(3–4):e383–e388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilkins AL, Sahara M, Till SR, et al. Effects of Shared Decision Making on Opioid Prescribing After Hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):823–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah BR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, Austin PC. Propensity score methods gave similar results to traditional regression modeling in observational studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):550–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cepeda MS, Boston R, Farrar JT, Strom BL. Comparison of logistic regression versus propensity score when the number of events is low and there are multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(3):280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sites BD, Harrison J, Herrick MD, Masaracchia MM, Beach ML, Davis MA. Prescription Opioid Use and Satisfaction With Care Among Adults With Musculoskeletal Conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill MV, Stucke RS, McMahon ML, Beeman JL, Barth RJ An Educational Intervention Decreases Opioid Prescribing After General Surgical Operations. Ann Surg. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallway A, Vu J, Lee J, et al. Patient Satisfaction and Pain Control Using an Opioid-Sparing Postoperative Pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(3):316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson M, Hallway A, Brummett C, Waljee J, Englesbe M, Howard R. Patient-Reported Outcomes After Opioid-Sparing Surgery Compared With Standard of Care. JAMA Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazar DJ, Zaveri S, Khetan P, Nobel TB, Divino CM. Variations in postoperative opioid prescribing by day of week and duration of hospital stay. Surgery. 2021;169(4):929–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mudumbai SC, Chung P, Nguyen N, et al. Perioperative Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Readmissions After Total Knee Arthroplasty in a National Cohort of Veterans Health Administration Patients. Pain Med. 2020;21(3):595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dasinger EA, Graham LA, Wahl TS, et al. Preoperative opioid use and postoperative pain associated with surgical readmissions. Am J Surg. 2019;218(5):828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vu JV, Cron DC, Lee JS, et al. Classifying Preoperative Opioid Use for Surgical Care. Ann Surg. 2020;271(6):1080–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waljee JF, Cron DC, Steiger RM, Zhong L, Englesbe MJ, Brummett CM. Effect of Preoperative Opioid Exposure on Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures Following Elective Abdominal Surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.