Abstract

Biocatalytic pathways for the synthesis of (−)-menthol, the most sold flavor worldwide, are highly sought-after. To access the key intermediate (R)-citronellal used in current major industrial production routes, we established a one-pot bienzymatic cascade from inexpensive geraniol, overcoming the problematic biocatalytic reduction of the mixture of (E/Z)-isomers in citral by harnessing a copper radical oxidase (CgrAlcOx) and an old yellow enzyme (OYE). The cascade using OYE2 delivered 95.1% conversion to (R)-citronellal with 95.9% ee, a 62 mg scale-up affording high yield and similar optical purity. An alternative OYE, GluER, gave (S)-citronellal from geraniol with 95.3% conversion and 99.2% ee.

Keywords: biocatalysis, biocascade, citronellal, citral, geranial, enzymatic oxidation, enzymatic reduction

The acyclic terpene citronellal–which gives off an intense lemon-, citronella-, and rose-type odor1–is a valuable molecule for its use in flavors and fragrances2 and is also of utmost importance as a precursor for the industrial synthesis of (−)-menthol, one of the chiral compounds with the largest commercial importance3 and one of the most sold flavors.4 Among the eight stereoisomers of menthol, only (−)-menthol holds the characteristic “cooling” effect and the peppermint minty odor, clean of off-flavor.5 Two of the three main industrial chemical synthesis routes to (−)-menthol (Supporting Information (SI) Scheme S1) employ (R)-citronellal (Scheme S2A) as an intermediate.6,7 In order to improve process sustainability and to provide access to alternative feedstock, alleviating the dependency on fossil or unstable natural resources,8 (R)-citronellal could be advantageously produced via biocatalytic approaches. Alternative routes harnessing inexpensive achiral substrates are especially sought-after.6 An ideal biocatalytic route would be the production of (R)-citronellal from the available, industrially relevant citral.9 This reduction reaction can be carried out using flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-containing ene-reductases of the old yellow enzyme (OYE; EC 1.6.99.1) family.10−12 Ubiquitous in Nature, OYEs are found in bacteria, fungi, plants, cyanobacteria, and recently algae13 and catalyze the asymmetric reduction reaction of a wide variety of α,β-unsaturated compounds.14−16 However, such a biocatalytic route remains challenging,17 since citral is found as a mixture of two isomers (geranial or (E)-isomer and neral or (Z)-isomer) (Scheme S2), which greatly influences the enantioselectivity of available OYEs.18 So far, no OYE has been able to achieve efficient conversion of citral and yield enantiopure (R)-citronellal with >95% enantiomeric excess (ee),19 as the enzymes tested were hampered by the presence of both citral isomers and despite enzyme engineering attempts,17,20,21 only OYE2p could reach 88.8% ee starting from an E/Z citral mixture of 10:9.22 To avoid the energetic-costly separation of citral isomers by distillation and prevent their isomerization,23 a direct approach would be to supply in situ the OYE with the appropriate E-isomer (i.e., geranial). To this end, we envisioned that a subfamily of copper radical oxidases (CROs), so-called CRO-AlcOx, able to oxidize a wide range of primary activated and unactivated alcohols to the corresponding aldehydes,24,25 could fulfill this role.

CRO-AlcOx (EC 1.1.3.13; AA5_226,27) are organic cofactor-free enzymes that recently emerged from the exploration of the fungal CROs family.24,28,29 CROs are better known through the archetypal galactose 6-oxidase from Fusarium graminearum (FgrGalOx; EC 1.1.3.9; AA5_2), extensively studied,30−34 engineered,35−41 and broadly applied42−47 since their initial discovery more than 60 years ago.48 Only recently a few studies have started to investigate the characteristics and application potential of CRO-AlcOx.25,49−51 A better understanding of these enzymes is needed to foster their use as biocatalysts. To date, CRO-AlcOx have never been evaluated for application in multistep enzymatic reactions, while alcohol oxidation is a key step in the synthesis route of many valuable chemicals.52 Similarly, OYEs, despite being known for decades, have been only marginally used in cascade reactions until recently.53 Coupling these two enzymatic systems together is therefore of interest to apprehend their potential in more complex environments and to probe their robustness and relevance for biotechnological applications.

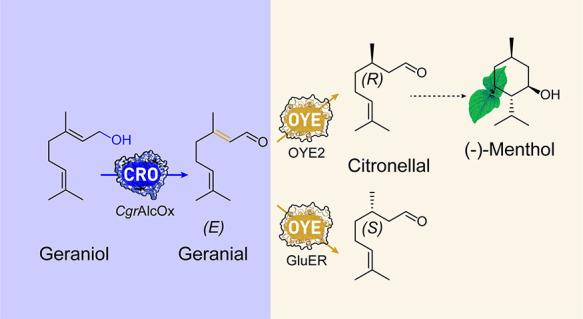

In this study, we developed a bienzymatic cascade composed of the CRO-AlcOx-catalyzed oxidation of the widely available terpene geraniol,54 to yield specifically geranial further hydrogenated by an OYE into either (R)-citronellal or (S)-citronellal (Scheme 1). This work unlocks access to (R)-citronellal with high optical purity using a wild-type OYE and establishes for the first time the use of a CRO-AlcOx in a multienzymatic cascade, contributing to a better understanding and control of these promising enzymes.

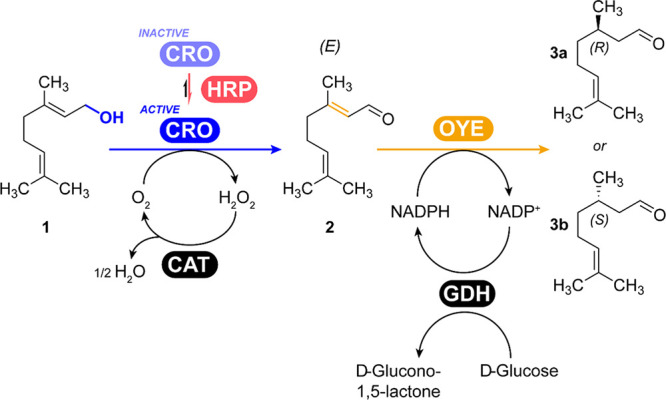

Scheme 1. Geraniol Oxidation by a CRO-AlcOx (Here CgrAlcOx) and Subsequent Geranial Reduction to (R)- or (S)-Citronellal by an OYE.

Compounds are (1) geraniol, (2) geranial, (3a) (R)-citronellal, and (3b) (S)-citronellal.

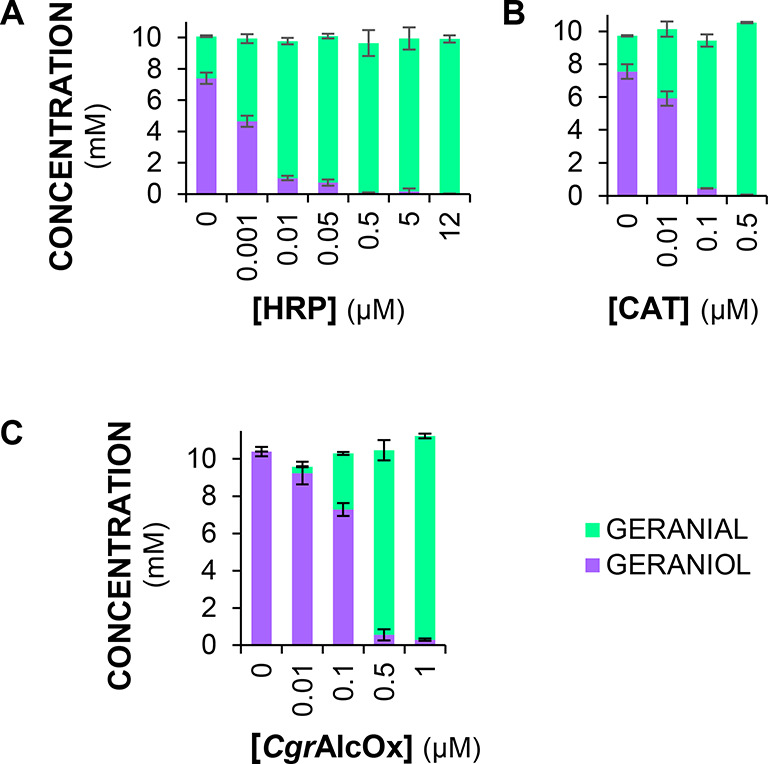

The initial step of the cascade was first considered. While geraniol had already been described as a good substrate of CgrAlcOx in a previous study,24 no conversion assay or product analysis was performed. We therefore evaluated the ability of CgrAlcOx to convert geraniol (10 mM), starting with previously established conditions on octan-1-ol,25 which include catalase (CAT) for in situ H2O2 dismutation, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for CgrAlcOx activation.49 We observed the facile conversion of geraniol (>99%, turnover number TON 10,000) in only 15 min (turnover frequency TOF 11.1 s–1), at mild temperature (23 °C), and the formation of one isomer of citral (Figure 1, Figures S12 and S13). This citral isomer was further identified as geranial by 1H NMR analysis (Figure S17) based on the study of Zeng et al.55 The concentrations of accessory enzymes CAT and HRP were then further investigated. As expected, both accessory enzymes are required to sustain the CgrAlcOx activity. A minimum of 0.5 μM HRP (Figure 1A) and 0.5 μM CAT (Figure 1B) were required to reach the maximum conversion efficiency. At least 1 μM CgrAlcOx was required for total conversion of geraniol in 15 min (Figure 1C). Interestingly, the HRP requirement was much lower here compared with that for the conversion of octan-1-ol in our previous study,25 which could be due to the activated nature of the substrate in this study, rendering its oxidation easier. While HRP has been used as a CRO activator for a long time,56 the underlying mechanism remains unclear. A direct protein–protein interaction between the peroxidase and the AlcOx could be involved.49

Figure 1.

CgrAlcOx-catalyzed oxidation of geraniol with (A) varying concentrations of HRP ([CAT] = 0.5 μM), (B) varying concentrations of CAT ([HRP] = 0.5 μM), and (C) varying concentrations of CgrAlcOx ([HRP] = 0.5 μM, [CAT] = 0.5 μM). For panels B and C, CgrAlcOx was used at 1 μM. Error bars represent standard deviation (s.d., independent experiments, n = 3). The legend in panel C applies also for panels A and B. All reactions were incubated for 15 min at 23 °C, under shaking (190 rpm).

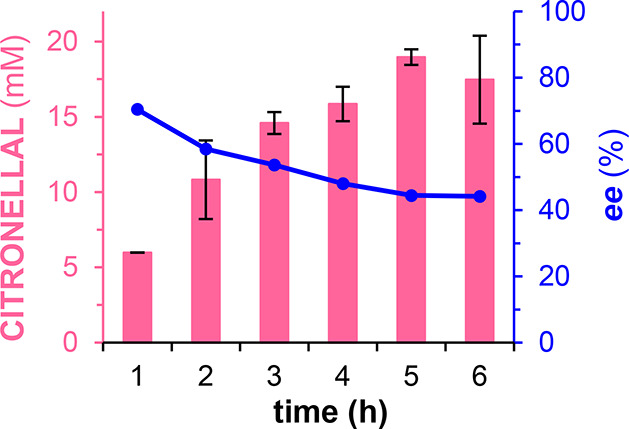

We then investigated the second part of the cascade (Scheme 1) to establish suitable conditions for the OYE-catalyzed reduction step, preferably resulting in enantiopure (R)-citronellal. Given the exceptionally fast formation of geranial by CgrAlcOx (TOF 11.1 s–1; Figure 1), it was desirable to identify conditions for a fast reduction by an OYE. The reduction step was investigated using citral (commercial mixture of neral and geranial). The supply of redox equivalents to the OYE was ensured by a NADPH regeneration system promoted by a glucose dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis (BsGDH). Initially, we investigated the influence of the concentration of OYE2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the reduction of 20 mM citral over 5 h (Figure S4). As expected, increased enzyme concentrations resulted in higher conversions, reaching 94.6% in 5 h with 10.67 μM OYE2, giving a TON of 1,773 and a TOF of 0.10 s–1. However, we observed that, with higher conversions, the ee of the product (R)-citronellal decreased (Figure S5). To investigate this decline in ee, we carried out a time-course monitoring of conversion and ee values over a 6 h reaction (Figure 2). As previously observed, with increased conversion over time, the ee decreased. We expected the OYE-catalyzed reduction of geranial to occur faster than that of neral,18 changing the ratio between geranial and neral over time. The consumption of neral eventually leads to (S)-citronellal, explaining the decreased optical purity of (R)-citronellal over time, although we currently lack an explanation why the ratio between the remaining geranial and neral showed only a small change in a nonlinear manner (Table S1). Finally, we explored the influence of the NADP+ concentration on conversion and observed that increased concentrations resulted in higher conversions with 1 mM and 2 mM NAPD+, compared with 0.1 and 0.5 mM (Figure S6).

Figure 2.

OYE2-catalyzed reduction of citral to citronellal over 6 h. The pink bars correspond to the concentration of the citronellal product (R + S enantiomers). The blue plot corresponds to the enantiomeric excess of (R)-citronellal versus (S)-citronellal. Reaction conditions: 20 mM citral, 10.67 μM OYE2, 1 mM NADP+, 40 mM glucose, 6 U/mL BsGDH, 100 mM KPi buffer pH 8.0, incubated at 25 °C and 300 rpm. Products were analyzed on a chiral GC-FID. Error bars represent standard deviation (s.d., independent experiments, n = 2).

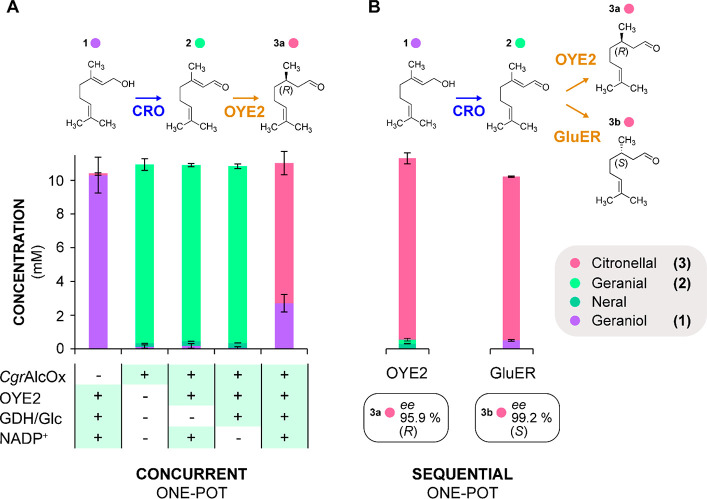

Based on the parameters we had determined for each individual enzymatic step, we then carried out the one-pot bienzymatic (CgrAlcOx and OYE2) cascade, starting from geraniol as substrate. By providing only geranial to the OYE2 thanks to the oxidation of geraniol by CgrAlcOx, we anticipated that the OYE2-catalyzed reduction should yield preferentially the (R)-citronellal.18 Accordingly, we observed the formation of (R)-citronellal with an ee ≥ 95% in 2.5 h (Figures 3A and S8). Parallel cascade experiments coupling CgrAlcOx with OYEs from Thermus scotoductus (TsOYE)57 or Gluconobacter oxydans (GluER)58 yielded the alternative (S)-citronellal product, with ≥99% ee (Figure S16) and respective conversion yields of 37% and 95.3%. Extending the reaction time from 16 to 24 h for TsOYE did not allow further improvement of the conversion yield (Figure S9), probably due to poor substrate affinity of TsOYE toward this β-substituted substrate.59,60 The use of higher temperature (i.e., 40 °C) for the conversion of citral by the TsOYE only brought a minor enhancement (Figure S7). A TsOYE double mutant with wider substrate specificity, TsOYE-C25D/I67T,61 only showed a 2-fold increase in conversions compared with the TsOYE wild type with ≥99% ee (Figure S7); therefore, GluER remained the best OYE to achieve high yield.

Figure 3.

Bienzymatic conversion of geraniol to citronellal by CgrAlcOx and OYEs. (A) Concurrent one-pot cascade reaction in 2.5 h with OYE2 to (R)-citronellal. (B) Sequential one-pot cascade reaction using either OYE2 (to (R)-citronellal) or GluER (to (S)-citronellal): first step (CgrAlcOx conversion of geraniol to geranial) performed in 15 min; second step (OYE conversion of geranial to citronellal) performed in 2.5 h. Analysis by GC-FID (error bars show s.d. independent experiments, n = 3). Note: the y axis displayed in panel A applies for panel B. Reaction conditions: 1 μM CgrAlcOx, 0.5 μM catalase, 0.5 μM HRP, 10.67 μM OYE2 or 8 μM GluER, 6 U/mL BsGDH, 40 mM glucose, 1 mM NADP+, pH 8.0 (50 mM NaPi buffer), 1% v/v acetone. Reactions were incubated at 23 °C, under shaking (200 rpm). For the reactions displayed in panel B, all reagents except for BsGDH were present at the first step; the second step was initiated by the addition of BsGDH to the reaction mixture.

When performing the full cascade in a concurrent one-pot system, we observed a proportion of geraniol that was not oxidized (Figures 3A and S14A). We conjectured that in the conditions we applied, CgrAlcOx could be partly inhibited by the final citronellal product. Indeed, conversions of geraniol by CgrAlcOx performed in the presence of exogenously added citronellal resulted in an incomplete reaction (Figure S10). Such observation is consistent with a hypothesis formulated previously on the possible inhibition of CgrAlcOx by hydrated alkyl-aldehydes.25,49 In the case of geranial, the conjugation effect stabilizes the molecule in its aldehyde form and disfavors its hydration, whereas citronellal does not benefit from this conjugation effect and would partly form geminal-diols upon hydration of the aldehyde,62,63 likely inhibiting CgrAlcOx.

To avoid initial CgrAlcOx inhibition with citronellal, we performed a sequential one-pot conversion (with OYE2) by running first a 15 min reaction with all reagents except BsGDH and leaving an additional 2.5 h of reaction after addition of BsGDH. Under these conditions, >99% of geraniol was converted and 95.1% of the intermediate geranial was converted to (R)-citronellal with 95.9% ee (Figures 3B and S14B).

Encouraged by the enantioenriched (R)-citronellal obtained with CgrAlcOx and OYE2, we carried out the bienzymatic cascade reaction at a larger scale, i.e. in a 20 mL reaction volume, with a starting concentration of geraniol of 20 mM (corresponding to 62 mg). To ensure the completion of the cascade, the reaction times were increased to 1 h for the alcohol oxidation step (catalyzed by CgrAlcOx), followed by 5 h for the conjugated alkene reduction step (catalyzed by OYE2). Additionally, prior to starting the reaction, the headspace and reaction media were saturated with pure oxygen to circumvent potential oxygen limitation in the first step. The resulting (R)-citronellal was simply extracted with ethyl acetate without further purification and characterized by chiral GC (Figure S15) and NMR spectroscopy (Figures S18 and S19). Conversion of the geraniol was 98% with a final isolated yield of 72% with 44.3 mg of (R)-citronellal with 95.1% ee. 1H NMR showed a highly pure product after extraction with ethyl acetate (Figure S18). Comparison of the catalytic efficiencies of the enzymes showed a TON of 17,458 (TOF 4.85 s–1) for CgrAlcOx and 1,636 (TOF 0.09 s–1) for OYE2. Considering that class III OYEs such as TsOYE afford the (S)-enantiomer exclusively,14 it is possible that the incomplete enantioselectivity observed with OYE2 (class II) may be due to kinetic differentiation.

To increase the catalytic efficiency of our system, small-scale experiments were carried out at higher substrate concentrations. Under the same reaction conditions as above, CgrAlcOx was able to convert 91% (±6.7%) of 50 mM geraniol in 2.5 h. The conversion was most likely hampered by lack of oxygen in the medium. Further upscaling of the reaction would require another reactor design to ensure sufficient oxygen supply to the CgrAlcOx. A possible solution to overcome the oxygen limitation would be the use of a segmented flow reactor that has recently been implemented in biocatalysis.64,65 We have previously demonstrated higher substrate concentrations for the OYE-catalyzed reaction along with others,66,67 and we do not foresee any limitations for further scale-up.

In conclusion, we established a one-pot bienzymatic cascade starting from inexpensive geraniol to specifically yield (R)-citronellal in high optical purity ≥95% ee, overcoming the problematic reduction of the mixture of (E/Z)-isomers in citral by OYEs.20 This cascade is tunable, by switching the OYE to produce the alternative enantiomer, and scalable, retaining the high optical purity. Together these results provide a biocatalytic method for the production of the key intermediate (R)-citronellal in the synthesis of (−)-menthol, the most sold flavor worldwide.4 We anticipate our biocatalytic cascade to provide an alternative route to achieve enantiopure (R)-citronellal and to expand the use of CRO-AlcOx as platform enzymes for multienzymatic reactions.

Acknowledgments

C.E.P. and G.T.H. acknowledge funding from the NWO Open Competition Science - XS (OCENW.XS4.291). D.R., B.B., M.L., and J.-G.B. acknowledge funding from the French National Agency for Research (“Agence Nationale de la Recherche”) through the “Projet de Recherche Collaboratif International” ANR-NSERC (FUNTASTIC project, ANR-17-CE07-0047). The Ph.D. fellowship of D.R. was funded by MANE V. Fils and the “Association Nationale Recherche Technologie” (ANRT) through the Convention Industrielle de Formation par la RecherchE (CIFRE) grant no. 2017/1169. We are grateful to D. J. Opperman for providing the plasmid for OYE2.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.1c05334.

Details on enzyme production and purification, experimental procedures, extended conversion data, GC chromatograms, and NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

⧧ D.R. and G.T.H. contributed equally.

Author Contributions

D.R. and G.T.H. carried out most of the experimental work, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; B.B. provided guidance in the experimental work. M.Y. drove the NMR experiments and the corresponding result interpretations and was involved in the manuscript writing; C.E.P., B.B., J.-G.B., M.L., and F.L. were involved in the study design and manuscript writing; C.E.P. conceptualized the study, supervised the work, and finalized the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Burdock G. A.Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients; CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Flavours and Fragrances: Chemistry, Bioprocessing and Sustainability; Berger R. G., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leffingwell J.; Leffingwell D. Chiral Chemistry in Flavours & Fragrances. Spec. Chem. Mag. 2011, 2011, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel A.; Steinhaus M.; Kotthoff M.; Nowak B.; Krautwurst D.; Schieberle P.; Hofmann T. Nature’s Chemical Signatures in Human Olfaction: A Foodborne Perspective for Future Biotechnology. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7124–7143. 10.1002/anie.201309508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surburg H.; Panten J.. Common Fragrance and Flavor Materials: Preparation, Properties and Uses, 6th ed.; Wiley-VCH, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bergner E. J.; Ebel K.; Johann T.; Löber O.. Method for the Production of Menthol. US7709688B2, 2010.

- Akutagawa S. Enantioselective Isomerization of Allylamine to Enamine: Practical Asymmetric Synthesis of (−)-Menthol by Rh–BINAP Catalysts. Top. Catal. 1997, 4, 271–274. 10.1023/A:1019112911246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sell C. S.Fundamentals of Fragrance Chemistry; Wiley-VCH, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hauer B. Embracing Nature’s Catalysts: A Viewpoint on the Future of Biocatalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8418–8427. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M.; Stueckler C.; Hauer B.; Stuermer R.; Friedrich T.; Breuer M.; Kroutil W.; Faber K. Asymmetric Bioreduction of Activated C=C Bonds Using Zymomonas mobilis NCR Enoate Reductase and Old Yellow Enzymes OYE 1–3 from Yeasts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 1511–1516. 10.1002/ejoc.200701208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M.; Stueckler C.; Ehammer H.; Pointner E.; Oberdorfer G.; Gruber K.; Hauer B.; Stuermer R.; Kroutil W.; Macheroux P.; Faber K. Asymmetric Bioreduction of C=C Bonds Using Enoate Reductases OPR1, OPR3 and YqjM: Enzyme-Based Stereocontrol. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 411–418. 10.1002/adsc.200700458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller N. J.; Stueckler C.; Hauer B.; Baudendistel N.; Housden H.; Bruce N. C.; Faber K. The Substrate Spectra of Pentaerythritol Tetranitrate Reductase, Morphinone Reductase, N-Ethylmaleimide Reductase and Estrogen-Binding Protein in the Asymmetric Bioreduction of Activated Alkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 387–394. 10.1002/adsc.200900832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Böhmer S.; Marx C.; Gómez-Baraibar Á.; Nowaczyk M. M.; Tischler D.; Hemschemeier A.; Happe T. Evolutionary Diverse Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Old Yellow Enzymes Reveal Distinctive Catalytic Properties and Potential for Whole-Cell Biotransformations. Algal Res. 2020, 50, 101970. 10.1016/j.algal.2020.101970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtissek A.; Tischler D.; Westphal A. H.; van Berkel W. J. H.; Paul C. E. Old Yellow Enzyme-Catalysed Asymmetric Hydrogenation: Linking Family Roots with Improved Catalysis. Catalysts 2017, 7, 130. 10.3390/catal7050130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toogood H. S.; Scrutton N. S. Discovery, Characterization, Engineering, and Applications of Ene-Reductases for Industrial Biocatalysis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3532–3549. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C. K.; Faber K.; Hall M. Biocatalytic Reduction of Activated C=C-Bonds and beyond: Emerging Trends. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 43, 97–105. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying X.; Yu S.; Huang M.; Wei R.; Meng S.; Cheng F.; Yu M.; Ying M.; Zhao M.; Wang Z. Engineering the Enantioselectivity of Yeast Old Yellow Enzyme OYE2y in Asymmetric Reduction of (E/Z)-Citral to (R)-Citronellal. Molecules 2019, 24, 1057. 10.3390/molecules24061057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A.; Hauer B.; Rosche B. Asymmetric Alkene Reduction by Yeast Old Yellow Enzymes and by a Novel Zymomonas mobilis Reductase. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 98, 22–29. 10.1002/bit.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougioukou D. J.; Walton A. Z.; Stewart J. D. Towards Preparative-Scale, Biocatalytic Alkene Reductions. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 8558–8560. 10.1039/c0cc03119d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress N.; Rapp J.; Hauer B. Enantioselective Reduction of Citral Isomers in NCR Ene Reductase: Analysis of an Active-Site Mutant Library. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 717–720. 10.1002/cbic.201700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Wei R.; Feng Y.; Jin L.; Jia Y.; Yang D.; Liang Z.; Han M.; Li X.; Lu C.; Ying X. Engineering of Yeast Old Yellow Enzyme OYE3 Enables Its Capability Discriminating of (E)-Citral and (Z.)-Citral. Molecules 2021, 26, 5040. 10.3390/molecules26165040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L.; Lin J.; Zhang B.; Kuang Y.; Wei D. Identification of a Yeast Old Yellow Enzyme for Highly Enantioselective Reduction of Citral Isomers to (R)-Citronellal. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 9. 10.1186/s40643-018-0192-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolken W. A. M.; ten Have R.; van der Werf M. J. Amino Acid-Catalyzed Conversion of Citral: cis–trans Isomerization and Its Conversion into 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one and Acetaldehyde. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 5401–5405. 10.1021/jf0007378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D.; Urresti S.; Lafond M.; Johnston E. M.; Derikvand F.; Ciano L.; Berrin J.-G.; Henrissat B.; Walton P. H.; Davies G. J.; Brumer H. Structure–Function Characterization Reveals New Catalytic Diversity in the Galactose Oxidase and Glyoxal Oxidase Family. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10197. 10.1038/ncomms10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeaucourt D.; Bissaro B.; Guallar V.; Yemloul M.; Haon M.; Grisel S.; Alphand V.; Brumer H.; Lambert F.; Berrin J.-G.; Lafond M. Comprehensive Insights into the Production of Long Chain Aliphatic Aldehydes Using a Copper-Radical Alcohol Oxidase as Biocatalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4411–4421. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur A.; Drula E.; Lombard V.; Coutinho P. M.; Henrissat B. Expansion of the Enzymatic Repertoire of the CAZy Database to Integrate Auxiliary Redox Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 41. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V.; Golaconda Ramulu H.; Drula E.; Coutinho P. M.; Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y.; Offen W. A.; Forget S. M.; Ciano L.; Viborg A. H.; Blagova E.; Henrissat B.; Walton P. H.; Davies G. J.; Brumer H. Discovery of a Fungal Copper Radical Oxidase with High Catalytic Efficiency towards 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Benzyl Alcohols for Bioprocessing. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3042–3058. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oide S.; Tanaka Y.; Watanabe A.; Inui M. Carbohydrate-Binding Property of a Cell Wall Integrity and Stress Response Component (WSC) Domain of an Alcohol Oxidase from the Rice Blast Pathogen Pyricularia oryzae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2019, 125, 13–20. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N.; Phillips S. E. V.; Yadav K. D. S.; Knowles P. F. Crystal Structure of a Free Radical Enzyme, Galactose Oxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 238, 794–814. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N.; Phillips S. E.; Stevens C.; Ogel Z. B.; McPherson M. J.; Keen J. N.; Yadav K. D.; Knowles P. F. Novel Thioether Bond Revealed by a 1.7 Å Crystal Structure of Galactose Oxidase. Nature 1991, 350, 87–90. 10.1038/350087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J. W. The Radical Chemistry of Galactose Oxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 433, 227–239. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J. W. Free Radical Catalysis by Galactose Oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2347–2364. 10.1021/cr020425z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadiut O.; Olsson L.; Brumer H. A Comparative Summary of Expression Systems for the Recombinant Production of Galactose Oxidase. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010, 9, 68. 10.1186/1475-2859-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Bulter T.; Alcalde M.; Petrounia I. P.; Arnold F. H. Modification of Galactose Oxidase to Introduce Glucose 6-Oxidase Activity. ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 781–783. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Petrounia I. P.; Yagasaki M.; Bandara G.; Arnold F. H. Expression and Stabilization of Galactose Oxidase in Escherichia coli by Directed Evolution. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2001, 14, 699–704. 10.1093/protein/14.9.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalettes F.; Turner N. J. Directed Evolution of Galactose Oxidase: Generation of Enantioselective Secondary Alcohol Oxidases. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 857–860. 10.1002/cbic.200700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman M. A.; Fryszkowska A.; Alvizo O.; Borra-Garske M.; Campos K. R.; Canada K. A.; Devine P. N.; Duan D.; Forstater J. H.; Grosser S. T.; Halsey H. M.; Hughes G. J.; Jo J.; Joyce L. A.; Kolev J. N.; Liang J.; Maloney K. M.; Mann B. F.; Marshall N. M.; McLaughlin M.; Moore J. C.; Murphy G. S.; Nawrat C. C.; Nazor J.; Novick S.; Patel N. R.; Rodriguez-Granillo A.; Robaire S. A.; Sherer E. C.; Truppo M. D.; Whittaker A. M.; Verma D.; Xiao L.; Xu Y.; Yang H. Design of an in vitro Biocatalytic Cascade for the Manufacture of Islatravir. Science 2019, 366, 1255–1259. 10.1126/science.aay8484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon S. E.; McPherson M. J. Enhanced Expression and Purification of Fungal Galactose Oxidase in Escherichia coli and Use for Analysis of a Saturation Mutagenesis Library. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 593–601. 10.1002/cbic.201000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon S. E.; Mahmoud K.; Spooner R. K.; Firbank S. J.; Knowles P. F.; Phillips S. E. V.; McPherson M. J. Enhanced Fructose Oxidase Activity in a Galactose Oxidase Variant. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 972–979. 10.1002/cbic.200300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippow S. M.; Moon T. S.; Basu S.; Yoon S.-H.; Li X.; Chapman B. A.; Robison K.; Lipovšek D.; Prather K. L. J. Engineering Enzyme Specificity Using Computational Design of a Defined-Sequence Library. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 1306–1315. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A. T.; Birmingham W. R.; Rehn G.; Charnock S. J.; Turner N. J.; Woodley J. M. Process Requirements of Galactose Oxidase Catalyzed Oxidation of Alcohols. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1580–1589. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parikka K.; Master E.; Tenkanen M. Oxidation with Galactose Oxidase: Multifunctional Enzymatic Catalysis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 120, 47–59. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham W.; Toftgaard Pedersen A.; Dias Gomes M.; Bøje Madsen M.; Breuer M.; Woodley J.; Turner N. J. Toward Scalable Biocatalytic Conversion of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural by Galactose Oxidase using Coordinated Reaction and Enzyme Engineering. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4946. 10.1038/s41467-021-25034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan B.; Debecker D. P.; Wu X.; Xiao J.; Fei Q.; Turner N. J. One-Pot Chemoenzymatic Deracemisation of Secondary Alcohols Employing Variants of Galactose Oxidase and Transfer Hydrogenation. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 6191–6195. 10.1002/cctc.202001191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilím J.; Knaus T.; Mutti F. G. Catalytic Promiscuity of Galactose Oxidase: A Mild Synthesis of Nitriles from Alcohols, Air, and Ammonia. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 14240–14244. 10.1002/anie.201809411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Spadiut O.; Araújo A. C.; Nakhai A.; Brumer H. Chemo-enzymatic Assembly of Clickable Cellulose Surfaces via Multivalent Polysaccharides. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 661–665. 10.1002/cssc.201100522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. A. D.; Smith W.; Bacila M.; Medina H. Galactose Oxidase from Polyporus circinatus, Fr. J. Biol. Chem. 1959, 234, 445–448. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget S.; Xia F. R.; Hein J. E.; Brumer H. Determination of Biocatalytic Parameters of a Copper Radical Oxidase Using Real-Time Reaction Progress Monitoring. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 2076–2184. 10.1039/C9OB02757B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeaucourt D.; Bissaro B.; Lambert F.; Lafond M.; Berrin J.-G. Biocatalytic Oxidation of Fatty Alcohols into Aldehydes for the Flavors and Fragrances Industry. Biotechnol Adv. 2021, 107787. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeaucourt D.; Saker S.; Navarro D.; Bissaro B.; Drula E.; Oliveira Correia L.; Haon M.; Grisel S.; Lapalu N.; Henrissat B.; O’Connell R. J.; Lambert F.; Lafond M.; Berrin J.-G. Identification of Copper-Containing Oxidoreductases in the Secretomes of Three Colletotrichum Species with a Focus on Copper Radical Oxidases for the Biocatalytic Production of Fatty Aldehydes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01526–21. 10.1128/AEM.01526-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Wu S.; Li Z. Recent Advances in Enzymatic Oxidation of Alcohols. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 43, 77–86. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrittwieser J. H.; Velikogne S.; Hall M.; Kroutil W. Artificial Biocatalytic Linear Cascades for Preparation of Organic Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 270–348. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Viljoen A. M. Geraniol — A Review of a Commercially Important Fragrance Material. South Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 643–651. 10.1016/j.sajb.2010.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S.; Kapur A.; Patankar M. S.; Xiong M. P. Formulation, Characterization, and Antitumor Properties of trans- and cis-Citral in the 4T1 Breast Cancer Xenograft Mouse Model. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 2548–2558. 10.1007/s11095-015-1643-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski L. D.; Kosman D. J. On the Role of Superoxide Radical in the Mechanism of Action of Galactose Oxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973, 53, 715–721. 10.1016/0006-291X(73)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman D. J.; Piater L. A.; van Heerden E. A Novel Chromate Reductase from Thermus scotoductus SA-01 Related to Old Yellow Enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 3076–3082. 10.1128/JB.01766-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter N.; Gröger H.; Hummel W. Asymmetric Reduction of Activated Alkenes Using an Enoate Reductase from Gluconobacter oxydans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 79–89. 10.1007/s00253-010-2793-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman D. J.; Sewell B. T.; Litthauer D.; Isupov M. N.; Littlechild J. A.; van Heerden E. Crystal Structure of a Thermostable Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus SA-01. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 426–431. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett N.; Duewel S.; Schmermund L.; Benary G. E.; Ranaghan K.; Mulholland A.; Opperman D. J.; Hoebenreich S. A Robust and Stereocomplementary Panel of Ene-Reductase Variants for Gram-Scale Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Mol. Catal. 2021, 502, 111404. 10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nett N.; Duewel S.; Richter A. A.; Hoebenreich S. Revealing Additional Stereocomplementary Pairs of Old Yellow Enzymes by Rational Transfer of Engineered Residues. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 685–691. 10.1002/cbic.201600688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat T.; Baiker A. Oxidation of Alcohols with Molecular Oxygen on Solid Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3037–3058. 10.1021/cr0200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings M. G.; Gasteiger J. Correlation Analyses of the Aqueous-Phase Acidities of Alcohols and gem-Diols, and of Carbonyl Hydration Equilibria Using Electronic and Structural Parameters. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1986, No. 3, 455–462. 10.1039/p29860000455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plutschack M. B.; Pieber B.; Gilmore K.; Seeberger P. H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11796–11893. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santis P. D.; Meyer L.-E.; Kara S. The Rise of Continuous Flow Biocatalysis – Fundamentals, Very Recent Developments and Future Perspectives. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 2155–2184. 10.1039/D0RE00335B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reß T.; Hummel W.; Hanlon S. P.; Iding H.; Gröger H. The Organic–Synthetic Potential of Recombinant Ene Reductases: Substrate-Scope Evaluation and Process Optimization. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 1302–1311. 10.1002/cctc.201402903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler D.; Gädke E.; Eggerichs D.; Baraibar A. G.; Mügge C.; Scholtissek A.; Paul C. E. Asymmetric Reduction of (R)-Carvone through a Thermostable and Organic-Solvent-Tolerant Ene-Reductase. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1217–1225. 10.1002/cbic.201900599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.