ABSTRACT

Background

The role of favipiravir (FVP) as a COVID-19 treatment is recognized but not fully elucidated. We aimed to evaluate whether FVP has definite clinical efficacy and safety in the treatment of COVID-19.

Methods

International and Chinese databases were searched for randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating FVP for the treatment of COVID-19. A meta-analysis was performed and published literature was synthesized to evaluate the corresponding therapeutic effects.

Results

We included 13 studies (1430 patients in total). Meta-analysis showed that patients with mild-to-moderate disease treated with FVP had a significantly higher viral clearance rate than those in the control group 10 and 14 days after initiation of treatment [RR: 1.13 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.28), P = 0.04; I2 = 39% for day 10 and RR: 1.16 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.30), P = 0.008; I2 = 38% for day 14] and a significantly shorter hospital stay [MD: −1.52 (95% CI: −2.82, −0.23), P = 0.02; I2 = 0%].

Conclusions

FVP significantly promotes viral clearance and reduces the hospitalization duration in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients, which can reduce the risk of severe disease outcomes in patients. However, more importantly, the results showed no benefit of FVP in severe patients, and caution should be taken regarding the treatment options of FVP in severe patients.

KEYWORDS: Antiviral agents, viral clearance, covid-19, favipiravir, meta-analysis

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

The urgent need to identify effective interventions to treat novel coronavirus infections is a major challenge. The role of favipiravir (FVP) as a COVID-19 treatment is recognized but not fully elucidated. Our study showed a significant correlation between viral clearance and the promotion of clinical improvement with FVP in mild-to-moderate patients, which is significant for reducing the length of hospital stay of patients, reducing the risk of patients progressing to severe disease, thereby reducing mortality. However, the results showed no benefit of FVP in severe patients and the conclusion of this study still needs to be further verified by clinical trials with large samples.

1. Introduction

Pneumonia associated with a novel coronavirus emerged in late December 2019, thus causing the ongoing worldwide coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, now named SARS-CoV-2, which quickly attracted global attention due to the increasing number of SARS-CoV-2 positive people [1]. The most common symptoms in patients with infection are fever, cough, myalgia and fatigue, while the uncommon symptoms include headache, dysgeusia, anosmia, skin lesions and gastrointestinal symptoms, etc., and even dyspnea, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute heart injury and other symptoms in severe cases [2–5]. While most people infected with SARS-CoV-2 are self-limited, it still causes serious loss of life and property worldwide [6]. As of 20 October 2021, the number of confirmed cases and deaths reported worldwide has reached 242,345,319 and 4,925,899, respectively, and the number continues to grow [7].

Currently, the therapeutic drug efficacy of COVID-19 is still debating [8]. The urgent need to identify effective interventions to treat novel coronavirus infections is a major challenge. To date, the commonly used antiviral drugs in clinical practice are hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), chloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV), and remdesvir, among others; despite a large number of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of several drugs against novel coronavirus, none have successfully shown good results of effective treatment [8,9].

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) plays a central role in the replication and transcriptional cycle of SARS-CoV-2, and docking studies have shown that antiretroviral drugs may be potential drugs for the treatment of COVID-19, especially favipiravir (FVP), chemically known as 6-fluoro-3-hydroxy-2-pyrazinecarboxamide, which selectively inhibits the RNA polymerase activity of the virus by binding to RdRp, was used in Japan in 2002 to treat influenza [10–16]. It has been considered as a safe and effective drug for the treatment of influenza and Ebola and was suggested by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China as one of the treatment modalities for SARS-CoV-2 patients because of its potential efficacy [8,17–20]. On 13 February 2020, FVP tablets were approved by the Chinese FDA (batch number: 2020L00005) for clinical trials of COVID-19. Cytological studies have shown that FVP can effectively inhibit VeroE6 cell (ATCC-1586)-induced SARS-CoV-2 infection, and FVP has been demonstrated to have activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro [21]. Recently, published animal experiments have demonstrated that it also has anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity in vivo [22,23].

Some meta-analyses have examined the efficacy and safety of FVP in the treatment of COVID-19, but they have the limitations of small sample size and lack of randomization of the sample [24–26]. Therefore, this paper will analyze FVP from two aspects, effectiveness and safety, to provide a more reasonable, effective and safe evidence-based basis for rational clinical drug use.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis. We registered the protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42021256322).

2.2. Search strategy

Both international (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Clinicaltrials.gov) and Chinese (CNKI, CBM, Chinese Journal Net, and WanFang) databases were searched by three researchers (WSD, CYY, SSY) independently from their start dates to 2 May 2021, using the search terms as follows: ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ OR ‘COVID-19 OR’ OR ‘SARS CoV-2’OR ‘2019-nCoV’ and favipiravir OR Avigan. The final PubMed search strategy can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Reference lists of review articles and original studies were manually searched to identify additional reports. No language was restricted in the search.

2.3. Inclusion criteria of the meta-analysis

The inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were formulated based on the PICOS acronym. Participants: Patients with SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed according to international or local diagnostic criteria, such as the Chinese diagnosis and treatment plan of COVID-19 patients (The sixth edition) and the WHO interim guidelines case definitions (WHO/2019 nCoV/Surveillance Case Definition/2020.1). Intervention: FVP with treatment as usual. Comparison: The standard of care (SOC), including other antiviral drugs or other treatment methods. Outcomes: The primary outcome was Percent Negative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction on Day 7, 10 and 14, calculated from the start of medication; the secondary outcomes were hospital stay, rate of need for oxygen support or mechanical ventilation, incidence of ICU transfer, all-cause mortality, adverse effects that were seen during the treatment and incidence of most common types of adverse reactions (hepatic function abnormal, blood uric acid increased and gastrointestinal Reactions). Study: Only published randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials were included. Case reports, reviews, protocols, in vitro studies, and retrospective studies were excluded.

2.4. Data extraction and quality assessment

Relevant data of eligible studies were extracted by three independent researchers (WSD, CYY, SSY), including study characteristics (such as study design, first author, geographical location, publication year), basic demographic and clinical data (such as disease severity, age, gender, drug name and dosage regimen) and outcomes (efficacy and safety of FVP). Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through consensus or referral to a senior researcher (JSC).

2.5. Statistical analyses

The random-effects model was adopted for all meta-analyzable results [27]. Meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.4 according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration [28]. The weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for continuous variables. The risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for categorical variables. A P value for Q test < 0.1 or I2 > 50% was defined as significant heterogeneity.

In the case of I2 ≥ 50% for percent negative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, we performed a sensitivity analysis to detect sources of heterogeneity after the removal of a nonrandomized study. In addition, the following three analyses were performed to detect the source of heterogeneity of the primary outcome: (i) Chinese vs. non-Chinese studies; (ii) mild to moderate disease studies vs. severe disease studies; and (iii) control group including HCQ vs. control group not including HCQ. Except for mortality, none of the other META analysis results detected publication bias by visual funnel plots because the sample size of the included articles was less than 10, which is of little significance [29].

2.6. Assessment of study quality

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed by three independent researchers (WSD, CYY, SSY) using the Cochrane tool for analyzing the risk of bias [30]. The overall level of evidence for all meta-analytic results was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system [31,32].

2.7. Ethics approval and Informed consent statements

As all analyses were based on previous published studies, no ethical approval or patient consent was required.

3. Results

3.1. Computer search

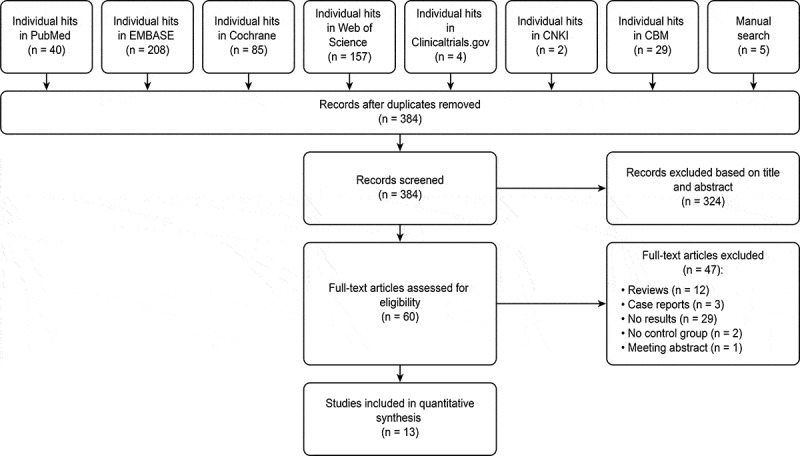

A total of 530 hits (Figure 1) were obtained from the database (n = 525) and manual search (n = 5). After removing 146 duplicates, 384 studies were screened. A total of 324 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening, and the full texts of 60 studies were then evaluated for eligibility. Finally, 13 studies were included in this meta-analysis, and a total of 47 articles were excluded for definite reasons (Figure 1) [33–45]. It is important to mention that two of the studies marked by a and b are different studies with the same first author and published in the same year, such as Dabbous et al. (2021a) and Dabbous et al. (2021b) [37,38].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and study selection

This figure described the route of study inclusion

3.2. Study characteristics

The 13 studies included 12 randomized controlled trials, covering 1430 patients, including 980 patients with mild to moderate disease and 450 patients with severe disease. Of the 13 studies, 5 were in China, 3 in Russia, 2 in Egypt, 1 in India, and 1 each in Iran and the Sultanate of Oman. Basic information of the included study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the included studies

| Study (country) | Study Design | Number of patients (I/C) |

Mean age: years (range) |

Sex: Male (%) |

Disease severity | Intervention | Control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (China) | RCT | 116/120 | Unclear (>18) |

I:50.9 C:42.5 |

Moderate to critical | FVP (1600 mg, twice the first day followed by 600 mg, twice daily, for the following days plus standard care for 7 days | Arbidol (200 mg, three times daily) plus standard of care for 7 days | [36] |

| Khamis et al. (The Sultanate of Oman) | RCT | 44/45 | I:54.0 C:56.0 (18–75) |

I: 64.0 C: 64.0 |

Moderate to severe | FVP 1600 mg on day 1 followed by 600 mg twice a day for a maximum of 10 days and interferon beta-1 at a dose of 8 million IU (0.25 g) twice a day was given for 5 days through a vibrating mesh aerogen nebulizer (Aerogen Solo) | The standard arm included the care based on the national guidelines that had HCQ 400 mg twice per day on the day 1, then 200 mg twice per day for 7 days. | [40] |

| Dabbous et al. (Egypt) | RCT | 44/48 | I:34.9 C:36.1 (18–80) |

I: 45.5 C: 52.1 |

Mild to moderate |

FVP 1600 mg BID on the first day and 600 mg bid from the day2-10, added to the standard-of-care therapy for 10 days | Chloroquine 600 mg tablets BID added to the standard-of-care therapy for 10 days | [37] |

| Dabbous et al. (Egypt) | RCT | 50/50 | I:36.3 C:36.4 (18–80) |

I: 50.0 C: 50.0 |

Mild to moderate | FVP 3200 mg at day 1 followed by 600 mg twice (day 2–day 10) | HCQ 800 mg at day 1 and 200 mg twice (day 2–10) and oral oseltamivir 75 mg/12 h/day for 10 days | [38] |

| Zhao et al. (China) | RCT | 7/5 | I:70.0 C:71.0 (>18) |

I: 71.4.0 C: 60.0 |

Moderate to severe | FVP 1600 mg, twice a day on the first day, and 600 mg, twice a day from the second day to the seventh day, orally. After seven days of treatment with FVP, the researchers decided whether to continue to use FVP according to the specific conditions of the subjects | Tocilizumab, the first dose was 4 − 8 mg/kg (recommended 400 mg) and added to 100 mL 0.9% normal saline (intravenous infusion time should be more than 1 h). For patients with fever, if there was still fever within 24 h after the first used, it should be used once more (the dose was the same as before). | [45] |

| Zhao et al. (China) | RCT | 36/19 | I:55.8 C:55.5 (28–79) |

I:44.4 C:47.4 |

Moderate | FVP 1600 mg, twice a day on the first day, and 600 mg, twice a day from the second day to the seventh day, orally. After seven days of treatment with FVP, the researchers decide whether to continue to use FVP according to the specific conditions of the subjects | Patients assigned to the control group received drugs other than favipiravir and treatment according to the needs of the disease. | [44] |

| Ivashchenko et al. (Russia) | RCT | 40/20 | Unclear (>18) |

Unclear | Moderate | AVIFAVIR 1600 mg BID on Day 1 followed by 600 mg BID on Days 2–14 (1600/600 mg), or AVIFAVIR 1800 mg BID on Day 1 followed by 800 mg BID on Days 2–14 (1800/800 mg) | SOC according to the Russian guidelines for treatment of COVID-19 | [39] |

| Balykova et al. (Russia) | RCT | 100/100 | I:49.7 C:49.7 (18–80) |

I:51.0 C:51.0 |

Moderate | FVP was 1600 mg twice a day on the 1st day and 600 mg twice a day on days 2–14 | Standard of Care will be prescribed in accordance with the recommended treatment regimens presented in the Russian guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 according to the decision of the Investigator | [33] |

| Balykova et al. (Russia) | RCT | 17/22 | I:47.2 C:47.5 (21–73) |

Unclear | Moderate | FVP was 1600 mg twice a day on the 1st day and 600 mg twice a day on days 2–14 | Twelve patients (54.5%) received a combination of HCQ and Azithromycin as an antiviral therapy, 8 patients (36.4%) – HCQ (monotherapy),2 patients (9.1%) -LPV/RTV. The dosage regimen was the following: for HCQ, it was 800 mg on the first day (400 mg twice a day); then, 400 mg/day (200 mg twice a day) for 2–7 days; for Azithromycin, 500 mg once a day for 5 days; for LPV/RTV, 400 mg+100 mg orally every 12 hours for 14 days. | [34] |

| Solaymani-Dodaran et al. (Iran) | RCT | 153/147 | I:58.6 C:56.6 (16–100) |

I:60.5 C:49.2 |

Moderate to severe | FVP 1600 mg stat and then 600 mg every 8 h plus HCQ 200 mg twice a day for 1 week | HCQ 400 mg followed by 100 + 400 LPV/RTV twice a day for 1 week. | [42] |

| Cai et al. (China) | Open label controlled study |

35/45 | I:43.0 C:49.0 (16–75) |

I:40.0 C:46.7 |

Mild to moderate | FVP (Day 1: 1600 mg twice daily; Days 2–14: 600 mg twice daily) plus interferon (IFN)-α by aerosol inhalation (5 million U twice daily) | LPV/RTV (Days 1–14: 400 mg/100 mg twice daily) plus IFN-α by aerosol inhalation (5 million U twice daily) | [35] |

| Lou et al. (China) | RCT | 9/10 | I:58.0 C:46.6 Unclear |

I:77.7 C:70.0 |

Severe | FVP was used in combination with the existing antiviral treatment. The first dose was 1600 mg or 2200 mg orally, followed by 600 mg each time, three times a day, and the duration of administration was not more than 14 days All of them were used in combination with interferon-α inhalation (100,000 iu, tid or qid). | Continue the existing antiviral treatment. The existing antiviral treatment included LPV/RTV (400 mg/100 mg, bid, po.) or darunavir/cobicistat (800 mg/150 mg, qd, po.) and arbidol (200 mg, tid, po.). All of them were used in combination with interferon-α inhalation (100,000 iu, tid or qid). |

[41] |

| Udwadia et al. (India) | RCT | 72/75 | I:43.6 C:43.0 (18–75) |

I:70.8 C:76.0 |

Mild to moderate | FVP (1800 mg BID loading dose on day 1; 800 mg BID maintenance) plus standard supportive care for up to a maximum of 14 days | Standard supportive care alone that included antipyretics, cough suppressants, antibiotics, and vita-mins | [43] |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; FVP, favipiravir; LPV, lopinavir; RTV, ritonavir; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine

3.3. Quality assessment of included study

Of the 13 studies, only 1 study was nonrandomized, and 5 studies did not report the method of randomization in detail, all of which were open-label except for Dabbous et al. [37]. The risk of bias summary, risk of bias graph and the quality of evidence for primary and secondary outcomes using the GRADE approach are reported in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S2.

3.4. The results of the meta‑analysis

3.4.1. Percent negative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on days 7, 10 and 14

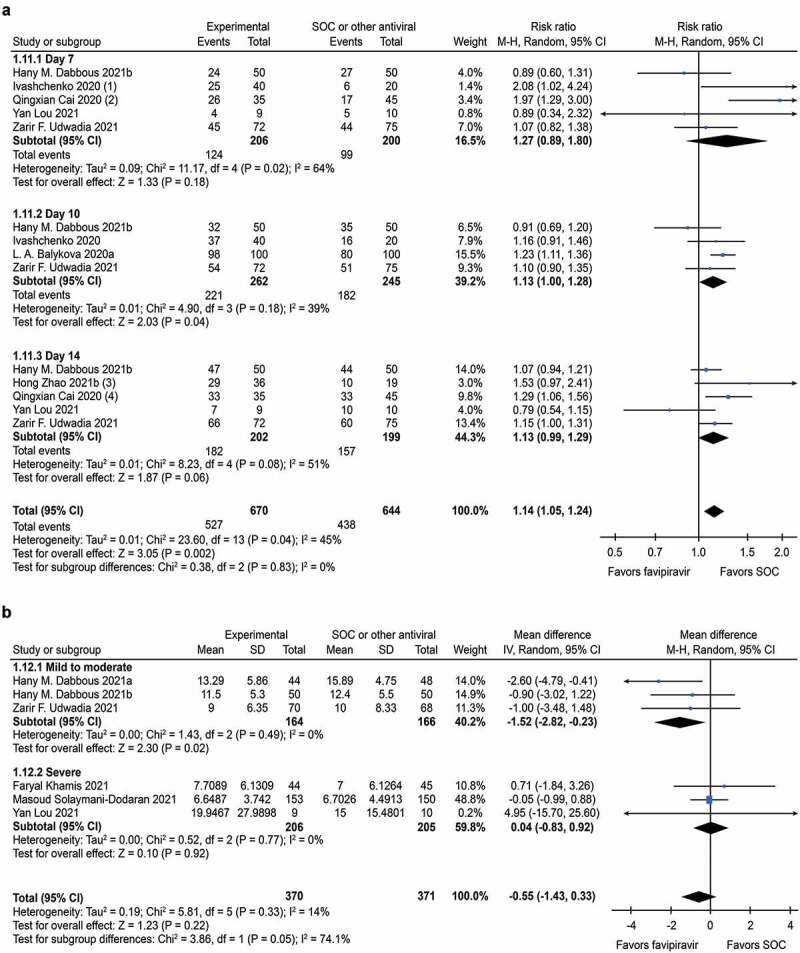

The results of the meta-analysis showed that viral clearance at day 10 after initiation of treatment was significantly higher in the FVP group than in the comparator group [RR: 1.13 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.28), P = 0.04; I2 = 39%]. Viral clearance was higher in the FVP group than in the control group on days 7 and 14 after initiation of treatment, but it was not statistically significant [RR: 1.27 (95% CI: 0.89, 1.80), P = 0.18; I2 = 65% for day 7 and RR: 1.14 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.29), P = 0.06; I2 = 51% for day 14] (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for Favipiravir in COVID-19

(a) Forest plot for negative percentage of RT-PCR.On day 10 after initiation of treatment, viral clearancewas significantly higher in the FVP group than in the control group. It should be mentioned that the study data of Ivashchenko 2020 and Cai 2020 were replaced by Day 5 and Day 8, respectively, instead of Day 7. Similarly, study data for Zhao 2021b and Cai 2020 replaced Day 14 with Day 30 and Day 16, respectively; (b) Forest plot for hospital stay. In mild-to-moderate studies, FVP was significantly superior to the control group in reducing the length of hospital stay. Abbreviations: FVP, Favipiravir; SOC, the standard of care.

There was a reduction in heterogeneity of viral clearance on days 7 and 14 [RR: 1.08 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.45), P = 0.58; I2 = 33% for day 7 and RR: 1.09 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.27), P = 0.24; I2 = 50% for day 14] (Supplementary Figure S2) after 1 nonrandomized study was removed, but it was still not statistically significant. Among the 3 subgroup analyses, the meta-analysis results of 4 small groups were statistically significant: non-Chinese studies [RR: 1.13 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.28), P = 0.04; I2 = 39% for day 10 and RR: 1.10 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.21), P = 0.03; I2 = 0% for day 14]. Mild to moderate disease studies [RR: 1.13 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.28), P = 0.04; I2 = 39% for day 10 and RR: 1.16 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.30), P = 0.008; I2 = 38% for day 14] (Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant change after sensitivity analysis for subgroup analyses.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of percent negative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on day 7, 10 and 14 after initiation of treatment

| Variables |

Active arms (Subjects) |

RR (95%CI) |

Day 7 I2 |

P | RR (95%CI) |

Day 10 I2 |

P | RR (95%CI) |

Day 14 I2 |

P | RR (95%CI) |

Total I2 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Chinese | 3(164) | 1.49 [0.71,3.13] | 55% | 0.29 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.16 [0.81, 1.64] | 70% | 0.42 | 1.26 [0.92, 1.74] | 68% | 0.15 |

| Non-Chinese | 4(507) | 1.12 [0.79, 1.60] | 54% | 0.52 | 1.13 [1.00, 1.28] | 39% | 0.04 | 1.10 [1.01, 1.21] | 0% | 0.03 | 1.12 [1.04, 1.21] | 22% | 0.002 |

| 2.Mild to moderate | 6(642) | 1.32 [0.90, 1.95] | 72% | 0.16 | 1.13 [1.00, 1.28] | 39% | 0.04 | 1.16 [1.04, 1.30] | 38% | 0.008 | 1.16 [1.07, 1.26] | 43% | 0.0004 |

| Severe | 1(29) | 0.89[0.34, 2.32] | N/A | 0.81 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.79 [0.54, 1.15] | N/A | 0.21 | 0.80 [0.56, 1.14] | N/A | 0.21 |

| 3. Control group includes HCQ | 3(360) | 1.29 [0.55, 3.01] | 77% | 0.55 | 1.13 [0.95, 1.34] | 56% | 0.18 | 1.07 [0.94, 1.21] | N/A | 0.30 | 1.11 [0.98, 1.26] | 49% | 0.09 |

| Control group does not include HCQ | 4(311) | 1.30 [0.80, 2.11] | 69% | 0.29 | 1.10 [0.90, 1.35] | N/A | 0.35 | 1.16 [0.96, 1.40] | 55% | 0.12 | 1.18 [1.03, 1.35] | 49% | 0.02 |

Bold P values: P < 0.05; CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable; RR, risk ratios;

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine

3.4.2. Hospital stay

In mild-to-moderate studies, FVP was significantly superior to the control group in reducing the length of hospital stay [MD: −1.52 (95% CI: −2.82, −0.23), P = 0.02; I2 = 0%] but not in severe disease studies [MD: 0.04 (95% CI: −0.83, −0.92), P = 0.92; I2 = 0%] (Figure 2B).

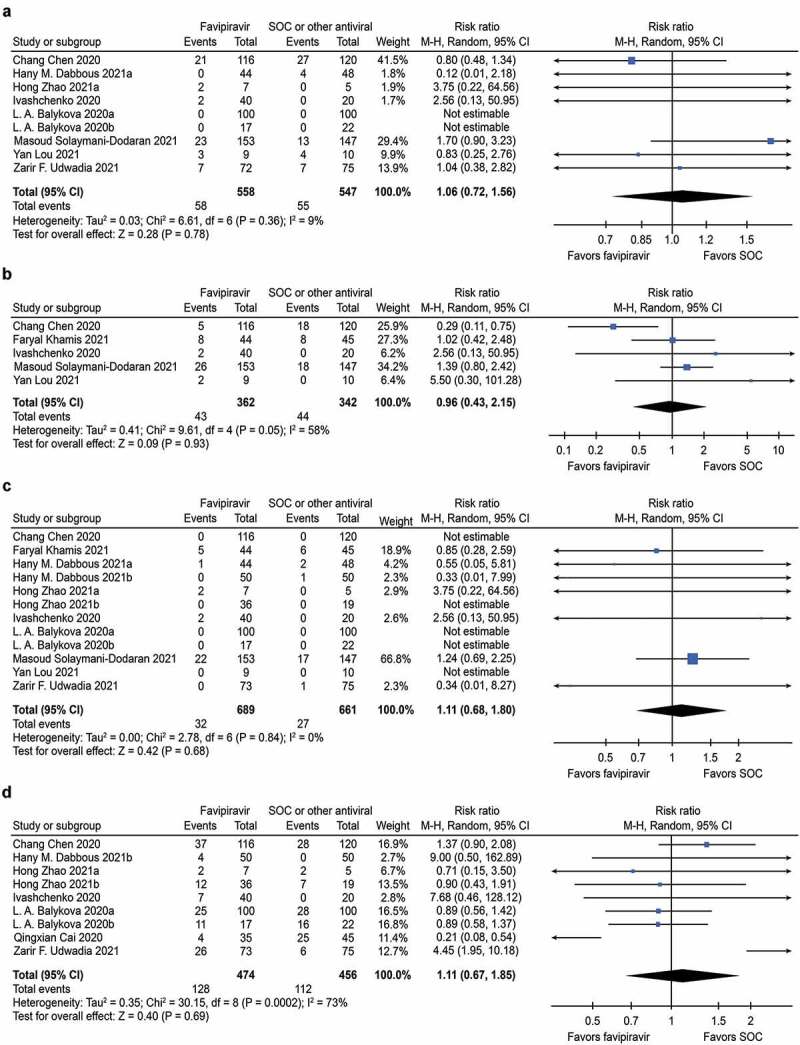

3.4.3. Rate of need for oxygen support or mechanical ventilation

No significant differences were found regarding the rate of need for oxygen support or mechanical ventilation [RR: 1.06 (95% CI: 0.72, 1.56), P = 0.78; I2 = 36%] (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for Favipiravir in COVID-19

(a) Forest plot for rate of need for oxygen support or mechanical ventilation; (b) Forest plot for transferred to ICU; (c) Forest plot for mortality; (d) Forest plot for adverse events. No significant differences were found regarding the above four outcome measures. Abbreviations: FVP, Favipiravir; SOC, the standard of care

3.4.4. Transferred to ICU

No significant differences were found regarding the incidence of ICU transfer [RR: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.43, 2.15), P = 0.93; I2 = 58%] (Figure 3B).

3.4.5. Mortality

No significant differences were found regarding mortality [RR: 1.11 (95% CI: 0.68, 1.80), P = 0.68; I2 = 0%] (Figure 3C), neither in mild to moderate studies nor in severe studies. Publication bias was not observed by visual funnel plots (Supplementary Figure S3).

3.4.6. Adverse events

No significant differences were found regarding the incidence of adverse effects that were seen during the treatment [RR: 1.11 (95% CI: 0.67, 1.85), P = 0.69; I2 = 73%] (Figure 3D).

Compared with the control group, almost all adverse reactions in the FVP group were mild and moderate. In the results of the meta-analysis, except for significantly elevated blood uric acid levels [RR: 4.65 (95% CI: 1.88, 11.51), P = 0.0009; I2 = 0%], abnormal liver function and gastrointestinal reactions were not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure S4).

4. Discussion

Although FVP has shown good promise and many studies have suggested them as a treatment modality for patients with SARS-CoV-2, there are still no social and organizational guidelines recommending the use of FVP in the management of COVID-19 [17,18,46,47]. Therefore, this study analyzed FVP from three aspects, efficacy, safety and systematic review, to provide a basis for future clinical decision-making, as follows.

(i) In terms of efficacy, this meta-analysis found that in patients with mild to moderate disease, patients taking FVP had significantly higher viral clearance on day 14 after initiation of treatment than patients taking other drugs, but this difference was not statistically significant on day 7, which may be related to the insufficient therapeutic dose and course of treatment of FVP. In another meta-analysis, Shrestha et al. reported that there was no significant difference in viral clearance between FVP patients at 7 and 14 days after initiation of treatment, which we hypothesized may be related to the insufficient number of studies and the small sample size included in the meta-analysis by Shrestha et al. [26].

Our meta-analysis found that mild-to-moderate patients taking FVP had significantly shorter hospital stays than patients taking other drugs. Balykova et al. reported a 4-day reduction in the mean length of hospital stay for patients taking FVP compared to patients in the control group but did not include this meta-analysis of the length of hospital stay because the study did not report a corresponding standard deviation [33]. Hassanipour et al., in a recently published meta-analysis, showed that patients in the FVP group had a significant clinical improvement compared to the control group at 7 days after initiation of treatment, and within 14 days, the clinical improvement rate in the FVP group was 10% higher than that in the control group, but it was not statistically significant [48].

Our study found that there was no significant difference in patients receiving FVP compared with the control group in terms of the need for supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. This conflicts with the conclusion that patients receiving FVP had less need for oxygen and mechanical ventilation reported by Shrestha et al. in a previous meta-analysis, which we hypothesized may be related to the insufficient number and small sample size of studies included in the meta-analysis by [26].

In addition, our study found that the incidence of ICU transfer was lower in patients taking FVP than in controls, but this difference was not statistically significant. In terms of all-cause mortality, the FVP group had a decrease in mild to moderate patients compared with the control group, but it was not statistically significant, and in severe patients, the FVP group had an increase compared with the control group, but it was also not statistically significant. We speculated that this may be related to the underlying diseases of the patients, such as hypertension and diabetes.

(ii) In terms of safety, this meta-analysis found that FVP had tolerable safety in terms of overall and serious adverse reactions compared with other drugs used for short-term treatment, with the most common reactions being gastrointestinal, such as nausea, diarrhea, elevated transaminases, elevated blood uric acid, etc., which was consistent with the conclusion of a review article [8]. However, the increase in serum uric acid is still a concern, and overall, more research evidence is still needed to prove the efficacy and safety of long-term medication with FVP.

As the drug most frequently appearing in the control group of included studies, HCQ was initially applied to the treatment of COVID-19 because of its potential benefit of attenuating the cytokine storm observed in moderate or severe COVID-19 forms and mitigating unfavorable outcomes, however, there is controversy regarding its efficacy and safety in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 [49]. Several studies have demonstrated that HCQ and azithromycin, alone or in combination, prolong the QTc interval, which can easily lead to myocarditis, a very common complication after infection with SARS-CoV-2 [50–54]. Balykova et al. reported that QTc prolongation was observed on the fifth day of treatment in 36.4% of patients taking HCQ relative to the FVP group [34]. No other studies were found to have QTc prolongation in the HCQ group in our included studies, so the corresponding meta-analysis was not performed. Further studies are expected to find evidence of whether FVP has better cardiac safety than HCQ.

(iii) In viral infections, natural killer (NK) cells, as part of the human immune system, are important front-line reactors for humans to resist viral infections [55,56]. However, NK cells may be a double-edged sword in the treatment of COVID-19, as it is one of the culprits in the development of cytokine storm syndrome, one of the most common causes of death in a new crown pneumonia [57,58]. In a recently published study, Reynard et al. applied FVP to treat Ebola virus in non-human primates and concluded that the reduction of viral load by FVP in early treatment is associated with a reduction in the release of related cytokines including NK cells, greatly reducing the incidence of developing cytokine storms, thereby reducing disease severity [59]. Interestingly, Ferri et al. reported a significant rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with autoimmune systemic diseases compared to the general population, but these patients tended to have relatively benign outcomes after diagnosis of COVID-19, possibly because such patients are themselves taking immunosuppressive agents (e.g. HCQ), thereby reducing the risk of cytokine storm syndrome [60]. This seems to mean that antiretroviral drugs combined with immunosuppressive agents may have better efficacy for COVID-19, and in a clinical randomized controlled trial, Zhao et al. reported that patients in the FVP plus tocilizumab group had better efficacy in improving pulmonary inflammation and inhibiting disease worsening than those in the FVP group, but it still needs to be further verified by clinical trials with large samples [45].

As another drug with potential efficacy, remdesivir is the first drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of COVID-19, and even if study claimed that FVP has higher viral clearance than remdesivir, further clinical trials are needed to prove it [61]. Unfortunately, there are no published controlled trials of FVP versus remdesivir in the treatment of COVID-19, thus related meta-analysis cannot be performed. It is worth mentioning that orally available FVP is superior to remdesivir requiring intravenous injection in both economy and availability, which facilitates administration at home by patients with SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed, especially those with concomitant immunodeficiency (such as chronic inflammatory immune-mediated diseases), which has a positive impact on early clearance of the virus and on disease transmission in the community [60,62].

Overall, although our study found no benefit of FVP in severe patients, it also showed that FVP has a significant correlation with viral clearance and promotion of clinical improvement in mild-to-moderate patients, which is significant for reducing the length of hospital stay, reducing the risk of severe outcome, and thereby reducing mortality, while shortening the time to viral shedding can also have an epidemic impact by reducing transmission to household contacts. As an effective oral antiviral drug, FVP not only facilitates patients with mild-to-moderate disease to take as early as possible, but is also expected to improve patient compliance and reduce the burden on already strained healthcare systems. However, the results shown that FVP does not have any benefit in severe patients, and we speculated that patients who come to seek care during epidemics may arrive too late after the onset of symptoms, with already have a massive viral load, so antiviral drugs cannot significantly counteract the progression of the disease, and therefore, taking FVP is more effective in early patients with lower viral loads, but its efficiency decreases if dosing is delayed after the onset of the disease.

There are some limitations to the included studies. Most studies simply described the randomization method as ‘random,’ did not determine whether its randomization method was appropriate, and were open-label, readily leading to selection bias. In the included studies, in some studies, the intervention group used other drugs in combination with FVP, such as interferon atomization inhalation, and a small number of studies used FVP with different doses and durations, which may have risks affecting the efficacy and safety of FVP. In addition, it is difficult to distinguish the tolerance of patients of different ages to the drug, and the medical conditions vary with study, which will cause certain bias in the study results. Overall, the results of this study need to be validated and refined by more large-scale prospective double-blind randomized controlled trials with strict designs and long-term follow-up.

5. Conclusions

In summary, FVP has a positive effect on viral clearance and a slightly shorter hospital stay in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, which is important to reduce the risk of patients progressing to severe disease. However, more importantly, the results of this study showed no benefit of FVP in severe patients, and caution should be taken regarding the treatment options of FVP in severe patients with COVID-19.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project (Clinical Pharmacy) and High Level Clinical Key Specialty (Clinical Pharmacy) in Guangdong Province, with the funder being the subsidy fund for medical service and security capacity improvement of the Central Department of Finance, code Z155080000004.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors should have substantially contributed to the conception and design of the review article and interpreting the relevant literature and have been involved in writing the review article or revised it for intellectual content.

Geolocation information

China

supplementary-material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Salzano G, et al. Olfactory and gustatory function impairment in COVID-19 patients: italian objective multicenter-study. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1560–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geremia N, Vito AD, Gunnella S, et al. A Case of Vasculitis-Like Skin Eruption Associated With COVID-19. Infectious Disease in Clinical Practice. 2020;28(6): e30–e31 [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vito A, Fiore V, Princic E, et al. Predictors of infection, symptoms development, and mortality in people with SARS-CoV-2 living in retirement nursing homes. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z, McGoogan JM.. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) - statistics and research. [Accessed20 October 2021]. : https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- 8.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, et al. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a review. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1824–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artese A, Svicher V, Costa G, et al. Current status of antivirals and druggable targets of SARS CoV-2 and other human pathogenic coronaviruses. Drug Resist Updat. 2020;53:100721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuta Y, Takahashi K, Fukuda Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of anti-influenza virus compound T-705. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(4):977–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallocchio RN, Dessì A, De Vito A, et al. Early combination treatment with existing HIV antivirals: an effective treatment for COVID-19? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(5):2435–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafi MO, Bhattacharje G, Al-Khafaji K, et al. Combination of QSAR, molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulation and MM-PBSA: analogues of lopinavir and favipiravir as potential drug candidates against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020;1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This is a study of molecular docking that addresses favipiravi as a potential drug for the treatment of COVID-19.

- 13.Buonaguro L, Tagliamonte M, Tornesello ML, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase as target for antiviral therapy. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuta Y, Komeno T, Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93(7):449–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naydenova K, Muir KW, Wu LF, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in the presence of favipiravir-RTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shannon A, Selisko B, Le NT, et al. Rapid incorporation of Favipiravir by the fast and permissive viral RNA polymerase complex results in SARS-CoV-2 lethal mutagenesis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du YX, Chen XP. Favipiravir: pharmacokinetics and Concerns About Clinical Trials for 2019-nCoV Infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(2):242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sissoko D, Laouenan C, Folkesson E, et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for Ebola Virus Disease (the JIKI Trial): a Historically Controlled, Single-Arm Proof-of-Concept Trial in Guinea. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatasubbaiah M, Dwarakanadha Reddy P, Satyanarayana SV. Literature-based review of the drugs used for the treatment of COVID-19. Curr Med Res Pract. 2020;10(3):100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kivrak A, Ulas B, Kivrak H. A comparative analysis for anti-viral drugs: their efficiency against SARS-CoV-2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021. 90 ;107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driouich JS, Cochin M, Lingas G, et al. Favipiravir antiviral efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in a hamster model. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaptein SJF, Jacobs S, Langendries L, et al. Favipiravir at high doses has potent antiviral activity in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters, whereas hydroxychloroquine lacks activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(43):26955–26965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manabe T, Kambayashi D, Akatsu H, et al. Favipiravir for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash A, Singh H, Kaur H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness and safety of favipiravir in the management of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) patients. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(5):414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Khadka S, et al. Favipiravir versus other antiviral or standard of care for COVID-19 treatment: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J. 2020;17(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J, Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Smith G, Davey SM, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(d5928):. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balykova LA, Govorov AV, Vasilyev AO, et al. Characteristics of covid-19 and possibilities of early causal therapy. Results of favipiravir use in clinical practice. Infektsionnye Bolezni. 2020;18(3): 30–40 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balykova LA, Pavelkina VF, Shmyreva NV, et al. Efficacy and safety of some etiotropic therapeutic schemes for treating patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19). Pharm Pharmacol. 2020;8(3): 150–159 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D, et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: an Open-Label Control Study. Engineering (Beijing). 2020;6(10):1192–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C, Zhang Y, Huang J, et al. Favipiravir Versus Arbidol for Clinical Recovery Rate in Moderate and Severe Adult COVID-19 Patients: A Prospective, Multicenter, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Front Pharmacol. 2021. 12 683296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dabbous HM, Abd-Elsalam S, El-Sayed MH, et al. Efficacy of favipiravir in COVID-19 treatment: a multi-center randomized study. Arch Virol. 2021;166(3):949–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Dabbous HM, El-Sayed MH, El Assal G, et al. Safety and efficacy of Favipiravir versus hydroxychloroquine in management of COVID-19: a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.Ivashchenko AA, Dmitriev KA, Vostokova NV, et al. AVIFAVIR for treatment of patients with moderate Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): interim results of a phase II/III multicenter randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021. 73(3) ;531–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khamis F, Al Naabi H, Al Lawati A, et al. Randomized controlled open label trial on the use of Favipiravir combined with inhaled interferon beta-1b in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:538–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lou Y, Liu L, Yao H, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Plasma Concentrations of Baloxavir Marboxil and Favipiravir in COVID-19 Patients: an Exploratory Randomized, Controlled Trial. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021;157:105631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solaymani-Dodaran M, Ghanei M, Bagheri M, et al. Safety and efficacy of Favipiravir in moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;95:107522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Udwadia ZF, Singh P, Barkate H, et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao H, Zhang C, Zhu Q, et al. Favipiravir in the treatment of patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive after discharge: a multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H, Zhu Q, Zhang C, et al. Tocilizumab combined with favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19: a multicenter trial in a small sample size. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;133:110825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolarin JA, Oluwatoyosi MA, Orege JI, et al. Therapeutic drugs for SARS-CoV-2 treatment: current state and perspective. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90:107228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayvargiya P, Garrigos ZE, Almeida NEC, et al. Treatment Considerations for COVID-19: a Critical Review of the Evidence (or Lack Thereof). Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(7):1454–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hassanipour S, Arab-Zozani M, Amani B, et al. The efficacy and safety of Favipiravir in treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pileggi GS, Ferreira GA, Reis A, et al. Chronic use of hydroxychloroquine did not protect against COVID-19 in a large cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases in Brazil. Adv Rheumatol. 2021;61(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Y, Li MX, Lu GD, et al. Hydroxychloroquine/Chloroquine as Therapeutics for COVID-19: truth under the Mystery. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(6):1538–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chorin E, Wadhwani L, Magnani S, et al. QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1425–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mercuro NJ, Yen CF, Shim DJ, et al. Risk of QT Interval Prolongation Associated With Use of Hydroxychloroquine With or Without Concomitant Azithromycin Among Hospitalized Patients Testing Positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(9):1036–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zequn Z, Yujia W, Dingding Q, et al. Off-label use of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and lopinavir/ritonavir in COVID-19 risks prolonging the QT interval by targeting the hERG channel. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021. 893 ;173813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costa P, Rusconi S, Mavilio D, et al. Differential disappearance of inhibitory natural killer cell receptors during HAART and possible impairment of HIV-1-specific CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes. AIDS. 2001;15(8):965–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soleimanian S, Yaghobi R. Harnessing Memory NK Cell to Protect Against COVID-19. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cron RQ, Caricchio R, Chatham WW. Calming the cytokine storm in COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1674–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeyaraman M, Muthu S, Bapat A, et al. Bracing NK cell based therapy to relegate pulmonary inflammation in COVID-19. Heliyon. 2021;7(7):e07635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reynard S, Gloaguen E, Baillet N, et al. Early control of viral load by favipiravir promotes survival to Ebola virus challenge and prevents cytokine storm in non-human primates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferri C, Giuggioli D, Raimondo V, et al. COVID-19 and rheumatic autoimmune systemic diseases: report of a large Italian patients series. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(11):3195–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article seems to confirm the relatively benign outcome of COVID-19 patients with autoimmune systemic diseases.

- 61.Kheirabadi D, Haddad F, Mousavi-Roknabadi RS, et al. A complementary critical appraisal on systematic reviews regarding the most efficient therapeutic strategies for the current COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. J Med Virol. 2021;93(5):2705–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sreekanth Reddy O, Lai WF. Tackling COVID-19 . Using Remdesivir and Favipiravir as Therapeutic Options. Chembiochem. 2021;22(6):939–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]